Abstract

Little is known about employee reactions in the form of un/ethical behavior to perceived acts of unfairness toward their peers perpetrated by the supervisor. Based on prior work suggesting that third parties also make fairness judgments and respond to the way employees are treated, this study first suggests that perceptions of interactional justice for peers (IJP) lead employees to two different responses to injustice at work: deviant workplace behaviors (DWBs) and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). Second, based on prior literature pointing to supervisors as among the most important sources of moral guidance at work, a mediating role is proposed for ethical leadership. The article suggests that supervisors who inflict acts of injustice on staff will be perceived as unethical leaders, and that these perceptions would explain why employees react to IJP in the form of deviance (DWBs) and citizenship (OCBs). Data were collected from 204 hotel employees. Results of structural equation modeling demonstrate that DWBs and OCBs are substantive reactions to IJP, whereas ethical leadership significantly mediates reactions in the form of DWBs and OCBs. Behavioral ethics and managerial implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employees’ perceptions about the fairness of the treatment they receive from their organizations have been extensively studied as an important factor in explaining why they decide to engage in un/ethical behavior (e.g., Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001; Greenberg 1990, 2002; Weaver and Treviño 1999; Masterson et al. 2000; Moorman 1991). Although the victim’s perspective has generally dominated this literature, some prior research on organizational justice suggests that third parties may also make fairness judgments and react to the way employees are treated (e.g., Skarlicki et al. 1999). Since the organization is the setting in which the fairness process has been most widely considered (Van den Bos 2005), this paper postulates that employees who observe acts of injustice toward their peers may be prone to intervene for ethical reasons (see for a review, Skarlicki and Kulik 2005), by preserving the well-being of the organization or engaging in workplace deviance (see Colquitt and Greenberg 2003, for a review).

One type of organizational justice that predicts un/ethical behavior at work is interactional justice, which refers to employees’ perceptions of the degree to which they are treated with respect and dignity by authority figures (Bies and Moag 1986). Perceived interactional justice toward others is probably the most important influence on employees’ perceptions of whether their coworkers are mistreated in the workplace (Alicke 1992). Thus, prior research and theory mention the effects of interactional justice as being more offensive than other types of fairness. Although third parties can view distributive and procedural justice violations as unfair (Brockner 1990; Skarlicki et al. 1998), the responsibility for distributive and procedural justice violations can be hard to pinpoint (Skarlicki and Kulik 2005). Furthermore, interpersonal justice violations signal that the transgressor not only lacks concern for justice, but also that he/she is not worried about saving the other person’s “face” (Goffman 1952). Therefore, in this study, third-party perceptions of employee (mis)treatment will be considered as employees’ perceptions of unfavorable interactional justice toward peers (IJP) perpetrated by the supervisor, one of the most relevant authority figures in the workplace (Bies and Moag 1986).

Prior literature on third-party intervention suggests that uninvolved third parties who witness injustices are willing to respond to mistreatment in a manner similar to that of an actor–victim in the situation, only less intensely (e.g., Lind et al. 1998; Sheppard et al. 1992; Tyler and Smith 1998; Walster et al. 1978). Although research on reactions to injustice has generally assumed an individualistic and rationally self-interested focus on justice for the self, i.e., “what’s in it for me?” (Treviño et al. 2006), some prior work suggests that employees in the workplace may also react to an organization based on the way they perceive the supervisor’s treatment of peers. Ethically, if they are aware of mistreatment of coworkers, employees may be inclined to respond deontically through an automatic and affect-based process (Folger et al. 2005), feeling unable “to look the other way” and engage in rationally self-interested reactions to do nothing (Gaudine and Thorne 2001). Therefore, this study first suggests that employees will react to interactional justice toward peers (IJP) by following behavioral patterns that are similar to when they suffer (mis)treatment themselves: in such a situation, employees will try to redress justice by reacting against the organization as the source of the injustice.

A review of the third-party literature shows punishment of offenders as a prevalent and salient intervention by observers of injustice (Carlsmith 2006; Okimoto and Wenzel 2011; Van Prooijen 2010), and a way to satisfy the victim’s (Gromet et al. 2012) and the observer’s demands for “just desserts” (see Darley 2002). Frequently used to predict behavioral ethics in work settings (Colquitt et al. 2001; Treviño et al. 2006; Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara 2010), deviant workplace behaviors (hereinafter, DWBs) and organizational citizenship behaviors (hereinafter, OCBs) are socially proscribed or exemplary activities, respectively, with which employees can punish an organization, inflicting considerable harm. DWBs are acts of misconduct that significantly violate organizational norms, putting at risk the well-being of the organization, its members, or both (Robinson and Bennett 1995), whereas OCBs are employee performances that substantially exceed moral minimums and promote the organization’s effectiveness (Organ 1988). Prior studies have documented the negative social effects of DWBs within organizations (Coffin 2003; Hollinger and Clark 1982, 1983; Murphy 1993; Robinson and Greenberg 1998). One survey, for example, concluded that 42 % of women reported being harassed at work (Gruber 1990). OCBs, on the other hand, are constructive behaviors highly regarded by managers that, if withdrawn by employees, may also cause considerable harm to the work group, leader or organization (Podsakoff and MacKenzie 1997; Rotundo and Sackett 2002; Wayne et al. 2002). The first aim of this study is, therefore, to test whether third-party employees who witness interactional justice toward peers (hereinafter, IJP) decide to intervene by engaging in DWBs and decreasing OCBs.

In addition to the scarce attention paid by ethical and organizational behaviorists to empirically testing third-party reactions to IJP in the form of ethical behavioral, there is also a lack of models to explain why these reactions are possible (rare exceptions include the attribution of responsibility model by Linke 2012). As mentioned above, third parties can care about others’ mistreatment because they are motivated by a moral imperative in which self-interest concerns are secondary (e.g., deonance model of fairness; Folger 2001). One issue at work that may influence employees to be morally motivated to respond to IJP is the leader’s performance when treating followers fairly or unfairly. Acting in this way, supervisors certainly ‘set a good or bad example’ for followers, and they can be a key source of moral guidance due to their proximity to their group and their ability to influence subordinate outcomes (Brown and Treviño 2006; Yukl 2002). Therefore, this study finally suggests that IJP predicts DWBs and OCBs because IJP elicits perceptions of ethical leadership among employees and, thus, may cause employees to be morally motivated to react to IJP.

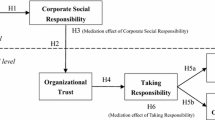

Before the paper examines the predicted mediating role of ethical leadership (H3), it will first provide evidence that IJP predicts DWBs (H1a) and OCBs (H1b), as well as ethical leadership (H2). Finally, the authors will discuss behavioral ethics and managerial implications of the findings.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

As mentioned earlier, DWBs and OCBs are two types of ethical conduct within organizations. OCBs are highly regarded by management, since employees voluntarily exceed role demands, while DWBs are clearly unacceptable. Examples of DWBs would include putting little effort into work and gossiping about and blaming co-workers, whereas cooperation with peers and assisting them with their duties would be examples of OCBs. Robinson and Bennett (1995) differentiate between DWBs directed at the organization (DWBOs) and those directed at individuals (DWBIs). Multidimensional delineations of OCBs have differentiated OCB facets, such as conscientiousness, sportsmanship, civic virtue, courtesy and altruism (Podsakoff et al., 1990), and divided OCBs into behavior directed mainly at individuals within the organization (OCBIs) and behavior more concerned with helping the organization as a whole (OCBOs) (Williams and Anderson 1991). In this regard, conscientiousness (often-called compliance), sportsmanship (tolerance without complaining), and civic virtue are seen as being directed at the organization (OCBOs), whereas courtesy and altruism are viewed as OCB dimensions mainly benefitting co-workers (OCBIs) (Williams and Anderson 1991; Van Dyne et al. 1995). Courtesy is defined as behavior that involves helping other members of the organization by taking steps to prevent the creation of problems, and altruism is defined as helping others with their work (Organ 1988).

Since supervisors carry out interpersonal acts of injustice toward peers, it is likely that in a first stage employees will react to their supervisor as the source of injustice. Although a deontic response transcends employees’ self-interest (Folger 2001), it is unlikely, however, that employees will retaliate against the leader overtly because this would most likely lead to formal sanctions or punishment. Instead, since leadership is a group phenomenon, employee retaliation is expected to be partially displaced toward the work group for which the supervisor is responsible. Employees would then perform behavior that, in harming the supervisor as the source of IJP, harms the group as well. Prior research supports this idea when suggesting that unfair treatment by a supervisor can result in retaliation against either the person him/herself, or the portion of the organization for which he or she is responsible (Ambrose et al. 2002; Rupp and Cropanzano 2002). All of this leads one to expect mainly interactional responses to IJP, such as gossiping about and blaming coworkers, lying to others, abandoning peers with problems to their fate, and not taking steps to support the well-being of the group. Therefore, in this study the criterion variables will consist of ethical behaviors directed at individuals (DWBIs and OCBIs) (Fig. 1).

Folger et al. (2005) differentiate justice from other types of social evaluations, suggesting that people care about justice intrinsically because of an affect-based process. Gaudine and Thorne (2001) state that emotions are especially present in moral decision-making. Unfavorable perceptions of interactional justice, or what others have described as interpersonal injustice (Greenberg 1993) or disrespect (Tyler and Blader 2000), may affect employees’ DWBs and OCBs by generating “hot” emotions, such as anger, resentment, or moral outrage (Bies and Tripp 1998; Bies et al. 1997; Robinson and Bennett 1997; Skarlicki and Folger 1997). These emotions provoked by IJP may result in employees empathizing with peers, placing themselves in their position, and having feelings similar to interactional justice for the self. A review of the third-party literature reveals that in organizational encounters, third-parties can internalize treatment of others that they consider unfair (Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara et al. 2013) and, hence, be reluctant “‘to look the other way”. Moreover, the IJP victim is probably a member of their group, thus making it especially likely that third parties will empathize with him or her. Even assuming the risk of retaliation by the supervisor, it is expected that members of the same collective will opt for a deontic (from the Greek, deon-: obligation) response, thus punishing the unfair treatment, even if they sacrifice personal gain in doing so (e.g., Turillo et al. 2002). Therefore, just as when they suffer injustice themselves, employees are expected to be guided by a moral imperative and respond to IJP in the form of DWBs and OCBs. Therefore,

H1a

DWBs will be negatively associated with employees’ perceptions of IJP.

H1b

OCBs will be positively associated with employees’ perceptions of IJP.

Brown et al. (2005) define ethical leadership as the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making. Furthermore, other formulations of what constitutes ethical leadership include principled decision-making (Avolio 1999), setting ethical expectations for followers (Treviño et al. 2003), and using rewards and punishments to hold followers accountable for ethical conduct (Gini 1998; Treviño et al. 2003). Unfavorable IJP may elicit perceptions of unethical leadership, that is, perceptions that a supervisor is lacking in principled decision-making, frustrating the ethical expectations of followers and applying non-contingent punishments to peers. As Treviño et al. (2000, 2003) suggest, leader behavior that shows little or no concern for employees contributes to perceptions of unethical leadership; therefore, perceived unfavorable IJP could predict it. Consequently,

H2

IJP will be positively associated with employees’ perceptions of ethical leadership.

As argued in this paper, the prediction that individual perceptions of IJP will lead employees to perform OCBs and DWBs can be justified by reactions based on a moral imperative (Folger 2001). However, it is unclear why employees are morally motivated to react to IJP in such an intrinsic way. Since IJP comprises perceptions of unfavorable acts of interactional justice toward peers perpetrated by the supervisor, there should be factors around the figure of the supervisor to explain why IJP is related to DWBs and OCBs. Researchers studying reactions to injustice from the victims’ perspective, such as Moorman and Byrne (2005) and Conlon et al. (2005), have offered support for this idea, examining pride and respect for or trust in the supervisor, as well as perceived organizational support and leader–member exchange, as explanations for reactions to injustice. However, these mediators mainly provide only a social exchange explanation for justice reactions in the workplace from the victim’s perspective, thus neglecting to address why employees are intrinsically motivated to respond to IJP morally.

This paper aims to extend the justice literature by suggesting the role of ethical leadership as a mediator in this link. The authors draw on prior literature proposing supervisors as among the most important sources of moral guidance for employees at work (Trevino and Brown 2005). Supervisors inflicting acts of injustice on staff are likely to be perceived as dishonest and untrustworthy, which may somehow influence employees’ reactions to mistreatment of peers. A basis for this assertion may be found in employee-centered implicit leadership theories (Bass 1990; Lord et al. 2001), which suggest that employees’ previous ideas about the figure of the supervisor create “schemas” that can determine the way employees evaluate (and react to) their supervisor’s performance. Implicit leadership theories are thought to develop based on events and experiences in a person’s life (Keller 1999), and they are generally rooted in the values and beliefs of the larger society and its subcultures (House et al. 2004). Parenting styles, for example, have been found to influence individuals’ implicit leadership theories, since parents often become the first leaders to which children are exposed (Keller 1999). Since implicit leadership theories point to prior social experiences as shaping “schemas” in employees minds that are used to evaluate supervisors, these schemas rest on ethical patterns rooted in the values and beliefs of the larger society and its subcultures (House et al. 2004). Employees are likely to compare this moral reference to the performance of their current leader at work. If incongruent, this mismatch can determine the way employees react to their supervisor’s performance (Bass 1990; Lord et al. 2001), producing moral-based reactions to IJP in the form of DWBs and decreased OCBs. Previous research seems to support this suggestion.

First, leader incongruence seems to rest on two distinct types of “schemas”, since ethical leaders have been referred to as a mixture of “moral persons” and “moral managers” (Treviño et al. 2000). From the moral person perspective, supervisors who mistreat peers are likely to be incongruent with what employees consider a good person, so that employees will probably disapprove of and dislike these supervisors. This probable aversion for supervisors who are viewed as “immoral people” may elicit emotional states generated by IJP, ultimately explaining why employees respond to IJP with destructive behavior. In this regard, Folger and Skarlicki (1998) contend that interactional justice is able to predict retaliation in the workplace because this mistreatment is perceived as a lack of personal sensitivity. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996, p. 37), with implicit leadership theories in mind, state that affective frameworks ‘appear to act as latent predispositions’, and individuals involved in negative affectivity are “predisposed to react more strongly to negative events”. If people care about IJP intrinsically because of an affect-based process (Folger et al. 2005), this lack of leader congruency may lead to DWBs and OCBs. In fact, leader incongruence with employees’ implicit leadership theories has been found to affect several employee outcomes, such as employees’ organizational commitment, job satisfaction and well-being (Epitropaki and Martin 2005).

Second, if this incongruence with employee implicit leadership theories elicits ethical leadership as “moral managers” in employees’ minds, it is likely that the leadership style of the supervisor will form part of the context in which employees’ moral motivations occur. In fact, leadership style has been shown to influence conformity in ethical decision-making frameworks in work groups (Schminke et al. 2002), and “moral manager” perceptions might play this mediating role. Brief et al. (2001) support this idea when stating that ways of thinking and acting can constitute a kind of organizational “moral microcosm”: an isolated style of moral thinking and acting that ethical managers may partly embody. If IJP leads to unethical leadership in the workplace, this “moral microcosm” may become inconsistent with the employees’ mental models or frameworks suggested by implicit leadership theories, deactivating them and, consequently, encouraging unethical behavior. In addition, faced with unethical managers, Bandura’s moral disengagement (1986, 1999) would also be more likely to occur. Finally, just as anomia (from the Greek, an-: absence, and -nomos: law) leads to misbehavior in societal contexts, “unethical managers” (and persons) could create a kind of anomic workplace context in which DWBs are encouraged (Cohen 1995; Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara 2008) and OCBs are withdrawn (Hodson 1999). Based on Emile Durkheim’s (1893/1897) original conceptualization, when anomie is present, the work group supporting people’s behaviors breaks down or is no longer effective, thus producing cynicism, valuelessness, disconnectedness, and amorality, which lead individuals to deviance (Cohen 1965; Cloward 1959).

In sum, ethical behavior motivations are highly susceptible to being explained via the mechanism that ethical leadership (rather than IJP directly) provides as a mediator in the relationship between IJP and ethical behavior. Accordingly, given that ethical leadership forms part of the mechanism underlying IJP’s link to OCBs and DWBs, the authors hypothesize that ethical leadership plays a mediating role by linking IJP perceptions with these two types of performance.

H3a

Perceptions of ethical leadership will mediate the relationship between perceptions of IJP and interpersonal DWBs.

H3b

Perceptions of ethical leadership will mediate the relationship between perceptions of IJP and interpersonal OCBs.

Method

Procedure and Sample Characteristics

The hypotheses were examined by collecting data from employees at eight upscale hotels in the Canary Islands, Spain in the summer of 2012. In all, 218 questionnaires were distributed personally in five sampled four-star hotels and three sampled five-star hotels in very similar percentages (from 16 to 22 %). The research project received official approval. Employees were chosen who met the criteria of working 6 months or more, so that they had a socialization period at the hotel. Fieldwork was performed with random respondents during their time at work, and surveyors asked them to fill the questionnaires out in different places and situations within the hotel, in order to avoid response biases due to uncontrolled contextual conditions. The sample comprised 45.6 % men and 54.4 % women. 44.6 % were 35 years of age or younger, and 3.4 % were 55 years of age or older. In addition, 55.4 % were permanent employees, and the remainder were temporary staff. Finally, 19.6 % of those responding had only finished primary school. Eventually, there were 204 valid responses, after six were rejected due to incorrect completion, and eight due to incoherent information.

The data analyses planned for this study include descriptive analyses, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation modeling (SEM). The collected data are analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS). Descriptive statistics include the mean, standard deviation of IJP, OCBs, DWBs, and ethical leadership. CFA is used to assess the validity of the measures, and SEM to test the hypothesized relationships through AMOS 17.0. The mediation tests follow the approach of Baron and Kenny (1986), Anderson and Gerbing (1988), and Sobel (1982). To ensure that the variables below are four separate constructs, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) will be used to inspect the fit of all the data to the four-factor structure, and the fit will be compared to that of the one-factor structure. The indices used include goodness-of-fit (GFI), comparative-fit (CFI), normed-fit (NFI), Tucker-Lewis (TLI), incremental-fit (IFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Measures

All items were scored on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree)—and in the case of DWBs and OCBs, from 1 (never) to 7 (constantly), and they are presented in the Appendix see Table 4. Cronbach’s alpha values appear on the main diagonal of the correlations matrix (Table 1).

Interpersonal Justice for Peers (IJP)

A scale of four (4) items was constructed by the authors, adapting scales from the literature on organizational justice for the self (e.g., Moorman 1991), and only including aspects of interactional justice.

Ethical Leadership

A ten-item measure developed by Brown et al. (2005) was employed.

Deviant Workplace Behavior (DWBs)

A seven-item scale developed by Bennett and Robinson (2000) was used to assess interpersonal DWB. Some items included in Bennett and Robinson’s scale (e.g., made an ethnic, religious, or racial remark at work) were not appropriate for the staff and hotel context under study, leading us to select three interpersonal DWB-related items.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCBs)

Interpersonal OCB, i.e., directed at individuals, was assessed using the eight-item scale developed by Lee and Allen (2002).

Results

The CFA results show that the four-factor solution is insufficient (χ 2 = 469.767, p < .001, df = 269, GFI = .86, CFI = .922, IFI = .922, TLI = .91, NFI = .837, RMSEA = .061), with a GFI index below .90 and RMSEA over .05. Since the fit of CFA for the four-factor solution is low, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is also performed. The EFA results are displayed in the Appendix Table 4. Two items (Y13 and Y18) on OCBs measures and one item (Y02) on ethical leadership were rejected and dropped because they did not load properly in their related factors. However, the remaining items loaded as predicted in the expected factors, confirming four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and no cross-loadings over .2 (this EFA without the dropped items is shown in full detail in the Appendix Table 4). Without these items, the fit of the four-factor solution (χ 2 = 296.262, df = 227, p < .001; GFI = .88, CFI = .96, IFI = .96, TLI = .96, NFI = .89, RMSEA = .048) is now sufficient and significantly better (∆χ 2d (25) = 987.4, p < .001) than the one-factor model (χ 2 = 1,283.662, df = 252, p < .001; GFI = .60, CFI = .63, IFI = .63 NFI = .59, TLI = .59, RMSEA = .15). These patterns provide additional support for the distinctiveness of the four constructs used in this study.

Table 1 shows the scale means, standard deviations, reliabilities and correlations (r) among all the variables. Results encounter significant inter-correlations among the four variables in the expected directions, indicating support for the hypotheses in this study.

SEM was used to test the relationships between the variables in this study. Figure 2 is a path diagram that shows the relationships between the observed variables (survey answers, in rectangles) and the unobserved latent variables (circles). The items provided in the Appendix Table 4 define the variables of the observed model. The various fit indices used, shown in Fig. 2, reveal a good fit of the model, above all RMSEA, which is .05. Support for H2 is provided by the significant path between IJP and ethical leadership (β = .51; p < .001). In addition, the main effects between IJP and DWBs (β = –.388; p < .001) and OCBs (β = .184; p < .05) were calculated by defining two SEM models whose details are shown in the first two lines of Table 2. The various fit indices used here, shown in Table 2, also reveal a good fit of these two models. These patterns support H1a and 1b.

To test H3a and 3b, first a nested models comparison was conducted using the sequential Chi square difference test (SCDT). Following Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) recommendations, our hypothesized model (more constrained) was compared to the saturated alternative model (less constrained), in which two direct paths from IJP to DWBs/OCBs were added. This latter model only represents a partially mediated model of the effects of IJP on DWBs/OCBs.

Table 2 shows the results of the comparison of the two models. In order to offer a more complete picture, two sub-models in which IJP separately links to DWBs and OCBs (see Table 2) were also compared. All the fully mediated models—the models with no direct paths linking IJP and OCBs/DWBs—were then compared with the partially mediated models, in which direct paths linking IJP to DWBs/OCBs were entered. The data in Table 2 reveal that the change in the Chi square test of the hypothesized model (χ 2 [227, 204] = 345.665), when compared to the saturated model (χ 2 [225, 204] = 331.259), is 14.406 for two degrees of freedom (∆χ 2 = 14.406; ∆df = 2). Given that the rule of thumb is that the change in Chi square divided by the change in degrees of freedom should be at least two, the Chi square test (SCDT) shows a significant change (∆χ 2d (2) = 14.406, p < .001) (∆χ 2/∆df = 7.203 > 2), thus supporting ethical leadership as a mediator between IJP and DWBs and OCBs. However, an inspection of the data for the two sub-models in Table 2 reveals that only the SCDT for the sub-model linking IJP to DWBs confirms a significant change (∆χ 2 = 13.786; ∆df = 1), since the change in the IJP-OCBs sub-model was not significant (∆χ 2d (1) = .035, p = .858). Hence, these patterns only support ethical leadership as a mediator in the link from IJP to DWBs.

Next, H3a and 3b were tested by inspecting the three Baron and Kenny (1986) conditions for mediation: (a) the independent variable [IJP] has to predict the criterion variables [DWBs/OCBs]; (b) the proposed mediator [ethical leadership] has to be predicted by the independent variable [IJP] and predict the criterion variables [DWBs/OCBs]; and (c), the direct path between IJP and DWBs/OCBs has to decrease (preferably to non-significance: full mediation) when the mediator [ethical leadership] is added. Support for H1 and H2, and the significant paths shown in Fig. 2 from ethical leadership to both OCBs (β = .312; p < .001) and DWBs (β = −.238; p < .01), allow the fulfillment of Baron and Kenny’s conditions (a) and (b). Moreover, Table 2 reveals that the third condition (c) of Baron and Kenny is fulfilled as well. That is, although IJP initially has significant main effects on DWBs (β = −.388; p < .001) and OCBs (β = .184; p < .05), when ethical leadership is added, these direct paths become less strong (β = −.360; p < .001) in the case of DWBs (partial mediation), and decrease to non-significance (full mediation) (β = .058; p n.s.) in the case of OCBs. Thus, these patterns support H3b and a partial mediation for DWBs (H3a).

Finally, the Sobel test and Preacher’s et al. (2007) bootstrapping method are also used to examine the significance of the mediating role of ethical leadership (H3a and 3b). The Sobel test shows whether the indirect effects of IJP on OCBs/DWBs via ethical leadership are different from zero. If a z score is larger than 1.96, then the hypotheses about the indirect effect are supported. The successive approximations calculation provides an estimate of the real indirect effect and its bias with a 95 % confidence interval (CI). Both methods demonstrate (see Table 3) that the mediating roles of ethical leadership in the relationship between IJP and OCBs/DWBs are significant (OCBs: .092 < CI95 % < .230, p < .001; DWBs: −.075 < CI95 % < −.171, p < .01). The confirmation of IJP’s indirect effects on OCBs and DWBs provided by the Sobel test also supports the mediation thesis; namely, the IJP has significant indirect effects on DWBs and (above all) OCBs through ethical leadership. Hence, these and all the above patterns support H3a about partial mediation and H3b about full mediation.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to test whether employees who observe acts of injustice toward peers (IJP) decide to respond to the organization by engaging in DWBs and OCBs directed at individuals, and to examine the usefulness of ethical leadership in further explaining the underlying psychological processes in these reactions. The results indicate that unfavorable IJP leads employees to react in the form of DWBs and decreased OCBs, and it makes them more prone to perceiving their supervisor as unethical. In turn, these perceptions of unethical leadership (and not IJP directly) are what actually significantly lead employees to react by engaging in OCBs, although this is only partially true in the case of DWBs. Overall, this study may offer several theoretical implications for behavioral ethics in organizations, drawing on the way the surveyed ethical context performed in predicting DWBs and OCBs. No less important are the specific new courses of action that the results of this study suggest for managers in organizations. Finally, the paper opens up several avenues for future research.

Given the little empirical attention that third-party justice-based intervention has received to date in organizational setting research, this paper is, first, able to present IJP as a “new type” of organizational justice that can lead employees to engage in two habitual forms of moral conduct in the workplace. Consistent with prior theory and research suggestions (e.g., Lind et al. 1998; Sheppard et al. 1992; Tyler and Smith 1998; Walster et al. 1978), third-party employees made fairness judgments and responded to the way employees were treated by performing interpersonal DWBs and OCBs. However, these findings challenge other research suggesting that inhibitors such as fear of ‘being next in line for similar treatment’ (Chaiken and Darley 1973) or the presence of others, as Darley and Latane’s (1968) classic study on the “bystander effect” suggested, can lead third parties to inaction. The present study does not propose that employees in our sample do not feel fear or vulnerability about subsequent mistreatment (see, for a review, Skarlicki and Kulik 2005). Instead, it is likely that they do feel intimidated, but these feelings do not keep them from responding to IJP. Thus, the idea that employees react to IJP by rejecting self-interested calculations like “it is someone else’s problem, not mine” gains strength, suggesting that third-party employees may respond to IJP due to a moral imperative to a great extent.

Certainly, the employees’ proximity to the peer–victim thought to be mistreated, and the consequent higher identification with that peer–victim, are situations that can play an important role in the above-mentioned results. If the focus of the mistreatment had been studied in other collectives (like co-workers from others groups and departments, customers, and so on), the results of this study would probably have been different. In any event, IJP seems to consist of more than just self-interested rationalizations. It involves moral injunctions, and the study of fairness in organizations may have to look for evidence of moral commitments to IJP that go beyond mere self-interest. The famous quote “to ignore evil is to become an accomplice to it” by Martin Luther King, Jr. (letter from Birmingham jail, April 16, 1963) illustrates this assertion.

The significant effects of IJP on ethical leadership, leading ethical leadership to predict DWBs and OCBs, show that perceptions of ethical leadership appear to be linked to all the variables in the model. In effect, in addition to being a significant cause of interpersonal DWBs and OCBs, ethical leadership is also an outcome of IJP in the tested model, suggesting that employees’ responses to IJP are elicited by moral judgments about the figure of the supervisor, particularly those showing concerns about his or her ethics. These patterns again appear to suggest that it is not rational choice theory and its assumption of self-interest, but rather a moral imperative, that is the underlying motive for reactions to perceptions of IJP. In addition, ethical leadership explains why IJP has behavioral implications in the form of DWBs and OCBs, as ethical leadership is supported as a partial or full mediator in the link between IJP and these types of employee performance. In sum, this mediating role for ethical leadership, and the DWBs’ and OCBs’ significant relation to all the variables in the tested model, could offer new insights to better understand employee reactions to mistreatment in organizational contexts. Before this study, the ethical leadership variable had not been found to be such a “breeding ground” for employees’ moral feelings elicited by IJP, particularly by unleashing or withering moral conduct that can substantially affect the effective functioning of the organization.

As mentioned above, regarding the links found to be mediated by ethical leadership, the results differ. In this study, ethical leadership was found to perform a full mediating role in its relationship with employees’ OCBs, but only partially with DWBs. Contrary to expectations, the results supported only a partial mediating effect of ethical leadership in the IJP-DWBs link, since they failed to accomplish all Baron and Kenny’s (1986) conditions for full mediation, or those of Sobel’s test (see Table 3). The question is why the results mainly support OCBs as employee reactions to IJP mediated by ethical leadership. Thus, the study seeks to shed light on why IJP is able to predict DWBs and ethical leadership, and the latter in turn predicts DWBs, but ethical leadership was unable to fully mediate the IJP-DWBs link. At first glance, using an argument based on symmetry, if the results suggest that OCBs are the consequence of “an act to redress justice” that is “transmitted” by ethical leadership, it seems logical to assume that unethical leadership should also be able to “transmit” the effects of unfavorable IJP on DWBs. Undoubtedly, here there is no symmetry to apply. An explanation for this “asymmetry” of the results probably lies in the fact that DWBs and OCBs are not two poles of the same construct, and the motivation and mechanisms underlying the two relationships may be somewhat different. In fact, some prior research has supported DWBs and OCBs as two correlated, but distinct constructs (e.g., Kelloway et al. 1999), thus suggesting that employees do not necessarily engage in the two behaviors for the same reasons. Perhaps OCB as a reaction to IJP is a positive moral emotion capable of being spread or discouraged by the supervisor’s ethics. However, DWBs may be less sensitive to this contagion. As such, these behaviors may be triggered by other reasons, such as ‘principled incompliance’, which somewhat relegate the supervisor’s ethics to the background. Moreover, according to our assessments, a lack of IJP may not exactly imply injustice, and “this lack of IJP” has been tested as predicting two opposite and distinct behaviors, DWBs and OCBs. One question for future research could be what would have happened if unfavorable IJP had been assessed as “injustice to peers” directly, instead of as justice to peers. Finally, this unpredicted result could also be explained by suggesting that the effects of IJP on DWBs are non-linear (i.e., curvilinear), so that they could vary as IJP decreases. Thus, DWBs’ moral contagion with unethical leadership may be stronger among respondents with low IJP, while those with high IJP might be less sensitive to ethical leadership, or vice versa. In this case, moral mechanisms may be less potent and less likely to be activated, so that in the whole relationship main effects would dominate without the mediating effect of ethical leadership.

Regarding the practical implications, in business contexts these findings may be useful in developing management strategies that favor organizational performance. IJP seems to constitute an important pillar in designing strategies to tackle employees’ destructive performance. Addressing events that show a lack of IJP seems to be important due to the ethical role that leadership plays in the psychological processes that lead employees to destructive performance, and in the main influences of IJP on DWBs and OCBs. Thus, leaving aside for the moment these mediating effects of ethical leadership on DWBs and OCBs, the way destructive performance among employees occurs is in fact twofold: not only will employees who suffered mistreatment react against the organization, but those who witness it will do the same. Therefore, if business managers have the idea that episodes of mistreatment toward subordinates are innocuous in encouraging destructive behavior in their peers, they might be using erroneous reasoning. Instead, actions designed to foster favorable IJP should have a prominent place in managers’ agendas.

The results suggest that managers should take action to control the appearance of both DWBs and OCBs. In addition, the results dealing specifically with the supported full mediation in the case of OCBs suggest that managerial actions designed to promote IJP are able to control OCBs because they send employees the message that their supervisors can be considered “ethical leaders”. Without doubt, the best way to get these employee perceptions to increase is for managers in organizations to hire and provide work groups with ethical leaders. Otherwise, destructive behavior can spread dangerously.

Limitations, Future Research, and Conclusions

Some questions remain that could form the basis for future research. First, there is a need to extend the span of what has been defined here as (in)justice “for others,” which can also include (in)justice for “customers.” Second, this extension could also be applied to (in)justice for peers, in that perceptions of other types of (in)justice by employees (i.e., procedural and distributive justices) can also be tested following similar patterns to those used in this paper. Finally, there is a need for research on the different effects that employees’ perceptions of (in)justice can have, depending on the different areas and services where employees work in the organization, since they can produce significant differences in the performance of the constructs used in this study. For example, episodes of (in)justice for peers in customers’ presence (e.g., for hotel receptionists during the guests’ check-in) may be thought of as especially cruel and, hence, more potent in triggering peers’ responses.

Concerning the limitations of our study, we acknowledge that, overall, the study contains some weaknesses. First, the study might suffer from mono-method/source bias. Second, the surveyed hotel employees have certain job conditions that are often inherent to their particular role in hotels and to guests in the hospitality industry. For example, hotel employees in our hospitality context are more prone to being observed by guests than employees in other settings in which customers are not present. Consequently, the performance of the constructs used in the present research, as well as their implications, could vary. Finally, the data stem from a limited universe, raising concerns about the generalizability of the findings.

This paper, on the other hand, contributes to a better understanding of why employees react to IJP by making decisions about helping or harming their organization. The almost-exclusive focus on injustice for the self has yielded patterns that do not sufficiently explain the role that IJP can play in these decisions. By perceiving acts of IJP, supervisors communicate to employees that they do not deserve to be labeled as ethical leaders, thus encouraging them to react in the form of interpersonal DWBs and OCBs. By supporting the mediating role of ethical leadership and uncovering main effects in the link between IJP and DWBs, and mainly OCBs, this study makes an important contribution to this portion of the justice and business ethics literatures: the importance of not only the victim’s reactions to injustice, but also the reactions of third parties.

References

Alicke, M. D. (1992). Culpable causation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 368–378.

Ambrose, M. L., Seabright, M. A., & Schminke, M. (2002). Sabotage in the workplace: The role of organizational justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 947–965.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step-approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Avolio, B. J. (1999). Full leadership development: Building the vital forces in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193–209.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bass, B. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications. New York, NY: Free Press.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 1, 43–55.

Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (1998). Revenge in organizations: The good, the bad, and the ugly. In R. W. Griffin, A. O’Leary-Kelly, & J. M. Collins (Eds.), Dysfunctional behavior in organizations: Non-violent dysfunctional behavior (pp. 49–67). Stamford, CN: Jai Press Inc.

Bies, R. J., Tripp, T. M., & Kramer, R. M. (1997). At the breaking point: Cognitive and social dynamics of revenge in organizations. In R. A. Giacalone & J. Greenberg (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in organizations (pp. 18–36). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brief, A. P., Buttram, R. T., & Dukerich, J. M. (2001). Collective corruption in the corporate world: Toward a process model. In M. E. Turner (Ed.), Groups at work: Theory and research (pp. 471–499). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brockner, J. (1990). Scope of justice in the workplace: How survivors react to co-worker layoffs. Journal of Social Issues, 46, 95–106.

Brown, M. E., Teviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2005), 117–134.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Carlsmith, K. M. (2006). The roles of retribution and utility in determining punishment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 437–451.

Chaiken, A. L., & Darley, J. M. (1973). Victim or perpetrator? Defensive attribution of responsibility and the need for order and justice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25, 268–275.

Cloward, R. A. (1959). Illegitimate means anomie, and deviant behavior. American Sociological Review, 24, 164–179.

Coffin, B. (2003). Breaking the silence on white collar crime. Risk Management, 50, 8.

Cohen, A. K. (1965). The sociology of the deviant act: Anomie theory and beyond. American Sociological Review, 30, 5–14.

Cohen, D. (1995). Ethics and crime in business firms: Organizational culture and the impact of anomie. In F. Adler & W. Laufer (Eds.), The legacy of anomie theory (pp. 183–206). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 278–321.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

Colquitt, J., & Greenberg, J. (2003). Organizational justice: A fair assessment of the state of the literature. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (2nd ed., pp. 165–210). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Conlon, D. E., Meyer, C. J., & Nowakowski, J. M. (2005). How does organizational justice affect performance, withdrawal, and counterproductive behaviour? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 301–327). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Darley, J. (2002). Just punishments: Research on retributional justice. In M. Ross & D. T. Miller (Eds.), The justice motive in everyday life (pp. 314–333). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Darley, J. M., & Latane, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 377–383.

Durkheim, E. [1893 (1984)]. The division of labor in society, (W.D. Halls, Trans.). New York: Free Press.

Durkheim, E. [1897 (1951)]. Suicide: A study in sociology, (J. A. Spaulding, & G. Simpson, Trans.). New York: Free Press.

Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2005). From Ideal to real: A longitudinal study of the role of implicit leadership theories on leader-member exchanges and employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 659–676.

Folger, R. (2001). Fairness as deonance. In S. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Research in social issues in management, pp. 3–31. Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Folger, R., Cropanzano, R., & Goldman, B. (2005). What is the relationship between justice and morality. In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt. Handbook of organizational justice, pp. 215–246. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Folger, R., & Skarlicki, D. P. (1998). A popcorn metaphor for workplace violence. In R. W. Griffin, A. O’Leary-Kelly, & J. Collins (Ed.), Dysfunctional behavior in organizations: Violent and deviant behavior, Vol. 23, pp. 43–81.

Gaudine, A., & Thorne, L. (2001). Emotion and ethical decision-making in organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 31(2), 175–187.

Gini, A. (1998). Moral leadership and business ethics. In J. B. Ciulla (Ed.), Ethics, the heart of leadership (pp. 27–45). Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Goffman, E. (1952). On cooling the mark out: Some aspects of adaptation to failure. Psychiatry, 15, 451–463.

Greenberg, J. (1990). Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: The hidden cost of pay cuts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 561–568.

Greenberg, J. (1993). The social side of fairness: Interpersonal and informal classes of organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: Approaching fairness in human resource management (pp. 79–103). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Greenberg, J. (2002). Who stole the money and when? Individual and situational determinants of employee theft. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 985–1003.

Gromet, D. M., Okimoto, T. G., Wenzel, M., & Darley, J. M. (2012). A Victim-centered approach to justice? Victim satisfaction effects on third-party punishments. Law and Human Behavior, 36(5), 375–389.

Gruber, J. E. (1990). Methodological problems and policy implications in sexual harassment research. Population Research and Policy Review, 9, 235–254.

Hodson, R. (1999). Organizational anomie and worker consent. Work and Occupations, 26(August), 292–323.

Hollinger, R. C., & Clark, J. P. (1982). Deterrence in the workplace: Perceived certainty, perceived severity, and employee theft. Social Forces, 62, 398–418.

Hollinger, R. C., & Clark, J. P. (1983). Theft by employees. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Keller, T. (1999). Images of the familiar: Individual differences and implicit leadership theories. Leadership Quarterly, 10, 589–607.

Kelloway, K., Loughlin, C., Barling, J., & Nault, A. (1999). Counterproductive and organizational citizenship behaviours: separate but related constructs. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10, 143–151.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 131–142.

Lind, E. A., Kray, L., & Thompson, L. (1998). The social construction of injustice: Fairness judgments in response to own and other’s unfair treatment by authorities. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75, 1–22.

Linke, L. H. (2012). Social closeness and decision making: Moral, attributive and emotional reactions to third party transgressions. Current Psychology, 31(3), 291–312.

Lord, R. G., Brown, D. J., Harvey, J. L., & Hall, R. J. (2001). Contextual constraints on prototype generation and their multilevel consequences for leadership perceptions. The Leadership Quarterly, 12, 311–338.

Masterson, S. S., Lewis-McClear, K., Goldman, B. M., & Taylor, M. S. (2000). Integrating justice and social exchange: The differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 67, 738–749.

Moorman, R. H. (1991). The relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 845–855.

Moorman, R., & Byrne, Z. S. (2005). What is the role of justice in promoting organizational citizenship behavior? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice: Fundamental questions about fairness in the workplace (pp. 355–382). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Murphy, K. R. (1993). Honesty in the workplace. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

Okimoto, T. G., & Wenzel, M. (2011). Third-party punishment and symbolic intragroup status. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(4), 709–718.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Impact or organizational citizenship behavior on organizational performance: A review and suggestions for future research. Human Performance, 10, 133–151.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Morrman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on follower’s trust in leader satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadership Quarterly, 1, 107–142.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D. & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 555–572.

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1997). Workplace deviance: Its definition, its manifestations, and its causes. In R. J. Lewicki & R. J. Bies (Eds.), Research on negotiation in organizations, Vol. 6 (pp. 3–27). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Robinson, S. L., & Greenberg, J. (1998). Employees behaving badly: Dimensions, determinants, and dilemmas in the study of workplace deviance. In C. L. Cooper & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), Trends in organizational behavior, Vol. 5 (pp. 1–30). New York: Wiley.

Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy-capturing approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 66–80.

Rupp, D. E., & Cropanzano, R. (2002). The mediating effects of social exchange relationships in predicting workplace outcomes from multifoci organizational justice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 925–946.

Schminke, M., Wells, D., Peyrefitte, J., & Sebora, T. C. (2002). Leadership and ethics in work groups. Group & Organization Management, 27, 272–293.

Sheppard, B. H., Lewicki, R. J., & Minton, J. W. (1992). Organizational justice: The search for fairness in the workplace. New York: Macmillan.

Skarlicki, D. P., Ellard, J. H., & Kelln, B. R. C. (1998). Third-party perceptions of a layoff: Procedural, derogation, and retributive aspects of justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 119–127.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997). Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 434–443.

Skarlicki, D. P., Folger, R., & Tesluk, P. (1999). Personality as a moderator in the relationship between fairness and retaliation. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 100–108.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Kulik, C. (2005). Third party reactions to employee mistreatment: A justice perspective. In B. Staw & R. Kramer (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, Vol. 26, 183–230.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Treviño, L. K., & Brown, M. E. (2005). The role of leaders in influencing unethical behavior in the workplace. In R. E. Kidwell & C. L. Martin (Eds.), Managing organizational deviance (pp. 69–96). London: Sage Publishing.

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 55, 5–37.

Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42, 128–142.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32, 951–990.

Turillo, C. J., Folger, R., Lavelle, J. J., Umphress, E. E., & Gee, J. O. (2002). Is virtue its own reward? Self-sacrificial decisions for the sake of fairness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 839–865.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2000). Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

Tyler, R. T., & Smith, H. J. (1998). Social justice and social movements. In D. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (4th ed., pp. 595–629). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Van den Bos, K. (2005). What is responsible for the fair process effect? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 273–300). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., & Parks, J. M. (1995). Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters). Research in Organizational Behavior, 17, 215–285.

Van Prooijen, J. W. (2010). Retributive versus compensatory justice: Observers’ preferences for punishment in response for criminal offenses. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 72–85.

Walster, E., Walster, G. N., & Berscheid, E. (1978). Equity: Theory and research. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., Bommer, W. H., & Tetrick, L. E. (2002). The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader–member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 590–598.

Weaver, G. R., & Treviño, L. K. (1999). Compliance and values oriented ethics programs: Influences on employees’ attitudes and behavior. Business Ethics Quarterly, 9, 315–337.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes, and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617.

Yukl, G. A. (2002). Leadership in organizations (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Zoghbi, P. (2008). Anomic employees and deviant workplace behaviour: An organisational study. Estudios de Psicología, 29(2), 181–195.

Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P. (2010). Do unfair procedures predict employees’ ethical behavior by deactivating formal regulations? Journal of Business Ethics, 94(3), 411–425.

Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P., Aguiar-Quintana, T., & Suárez-Acosta, M. A. (2013). A justice framework for understanding how guests react to hotel employee (mis)treatment. Tourism Management, 36, 143–152.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P., Suárez-Acosta, M.A. Employees’ Reactions to Peers’ Unfair Treatment by Supervisors: The Role of Ethical Leadership. J Bus Ethics 122, 537–549 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1778-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1778-z