Abstract

Using Leventhal’s (Social exchange: Advances in theory and research, Plenum Press, New York, 1980) rules of procedural justice as well as deontic justice (Folger in Research in social issues in management, Information Age, Greenwich, CT, 2001), we examine how personal value for diversity moderates the negative relationship between perceived discrimination against minorities (i.e., racial minorities and females) at work and the perceived procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization. Through a field survey of 190 employees, we found that observers high in personal value for diversity have stronger negative reactions to the mistreatment of women and racial minorities than observers low in personal value for diversity. These findings support and extend the deontic justice perspective because those who personally value diversity had the strongest negative reactions toward the discriminatory treatment of minorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As the number of minorities in the US continues to grow (US Census Bureau 2007, 2008), it is clear that diversity at work is a fact of life that must be managed (Cox 1994). However, a fair amount of evidence indicates that discrimination in the workplace exists (Dipboye and Colella 2005; Goldman et al. 2006; Tomaskovic-Devey et al. 2005). In 2010, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) received 99,922 claims of discrimination. Over 35,000 of these charges were race related and over 29,000 were sex related (EEOC 2011). Reflecting this reality, much research attention has been paid to discrimination itself (Dipboye and Colella 2005) as well as the effectiveness of diversity management programs (e.g., Kalev et al. 2006) and the impact of employee perceptions of diversity climate on individual reactions (e.g., Kossek and Zonia 1993; McKay et al. 2007; Mor Barak et al. 1998; Mor Barak and Levin 2002; Triana et al. 2010). What has been relatively ignored in the literature is how one’s personal values influence one’s reactions to discrimination against minorities at work. To fill this research gap, we shed light on this question.

Related to discrimination against minorities, we focus on the procedural justice of minorities as our dependent variable of interest. Procedural justice, or the perceived fairness of the procedures used to make decisions in organizations (Colquitt 2001; Leventhal 1980; Leventhal et al. 1980; Thibaut and Walker 1975), is important because it influences a variety of employee attitudes and outcomes, including employee satisfaction, commitment, citizenship behavior, and job performance (Colquitt et al. 2001; Folger and Konovsky 1989; Konovsky 2000; Niehoff and Moorman 1993). The majority of procedural justice research has had a “first-person” focus (Kray and Lind 2002) on individuals’ perceptions about the fairness of the procedures at work that impact them personally. Less research has been conducted on how procedures at work affect others in the organization. Given that reality in organizations is socially constructed through information in the work environment (Salancik and Pfeffer 1978) and that the perceived justice of others can influence one’s own procedural justice judgments (e.g., Colquitt 2004; Lind et al. 1998; Van den Bos and Lind 2001), an examination of the procedural justice of others in organizations is relevant.

We examine how employees’ perceptions of discrimination against minorities (i.e., racial minorities and females) in their organizations are related to their judgments of the procedural justice of those minorities’ treatment by the organization. We argue that perceived discrimination against minorities should be negatively related to the perceived procedural justice of those minorities, because discrimination violates Leventhal’s rules (1980) for procedural justice. This is also consistent with the deontic justice perspective (Cropanzano et al. 2003; Folger 2001; Folger et al. 2005), which focuses on the role of what is morally correct in the justice judgment process.

In addition to investigating the negative relationship between discrimination against minorities and the perceived procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization, we examine how personal value for diversity can amplify the negative relationship between these variables. This has not been examined before even though personal value for diversity should matter, because when justice is in the eye of the beholder, the values of the beholder will likely modify justice perceptions. We define personal value for diversity as the importance a person places on having a diverse group of individuals in the workplace. This is based on the study of Mor Barak et al. (1998), who stated that personal value for diversity involves an individual’s views toward diversity at work that can affect attitudes and behaviors toward others in the organization.

Our study makes several contributions. Theoretically, it answers calls to examine discrimination and procedural justice together (i.e., Dipboye and Colella 2005; Hicks-Clarke and Iles 2000; Stone-Romero and Stone 2005). This is the first study to use the deontic justice perspective, which maintains that people use their moral values to determine what is fair and unfair (Folger 2001), to examine personal value for diversity as a moderator of the relationship between perceived discrimination against minorities and judgments about the procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization. While research has empirically linked self-discrimination and self-procedural justice (Triana and García 2009), no research has yet examined ratings of others’ discrimination and others’ procedural justice in spite of their importance to research and practice.

Practically, our study provides evidence about the way people react when they see discrimination against minorities at work. This information is useful for practitioners, including managers, because the results of this study suggest that the negative consequences of discriminatory treatment may have effects on observers. Not only is discrimination both legally and morally wrong (Demuijnck 2009; Dipboye and Colella 2005), but such actions also send a signal to other employees about the integrity of the organization and its leaders (Goldman et al. 2008; Salancik and Pfeffer 1978). In addition, discrimination against minorities is problematic because perceived procedural justice for others and one’s own perceived procedural justice from the organization are correlated (Colquitt 2004).

Theory and Hypotheses

Justice concerns may be triggered through perceived discriminatory treatment. Consistent with Allport (1954), we define discrimination as denying some individuals equal treatment compared to others because of their demographic characteristics. Perceived discrimination against minorities will most likely lead people to conclude that the organization’s treatment of minorities is procedurally unfair (Triana and García 2009). Procedural justice is defined as the fairness of the procedures, or processes, that are used to arrive at an individual’s work outcomes (Leventhal 1980; Leventhal et al. 1980; Thibaut and Walker 1975). Leventhal’s seminal work (1980) established six rules for judging procedural fairness: the consistency rule, which highlights that procedures should be consistent across persons; the bias suppression rule, or the avoidance of self-interest and narrow preconceptions; the accuracy rule, which emphasizes the gathering of solid information and informed opinions in processes used to allocate outcomes; the correctability rule, or availability of opportunities to modify and reverse decisions made; the representativeness rule, which states that an allocation process should reflect the concerns and values of the groups affected by the process in question; and the ethicality rule, or the compatibility of the allocation procedures with the observer’s moral and ethical values.

Individuals who perceive discrimination against minorities at work are likely to believe that at least three rules were violated: consistency, bias suppression, and accuracy (Leventhal 1980). Discriminatory treatment is not consistent across persons because some people are favored over others. It is not free from bias because those who discriminate usually favor their in-group members due to similarity attraction (Byrne 1971) and social categorization (Tajfel and Turner 1986). Discriminatory treatment represents inaccurate information because people are being treated differently from others on the basis of non-work-related reasons. Thus, based on Leventhal’s rules, perceived discrimination against minorities should be negatively related to perceived procedural justice of minorities.

Furthermore, this main effect should be moderated by personal value for diversity, as noted in the deontic justice perspective. The word “deontic” is based on the Greek root, “deon, referring to obligation or duty” (Folger 2001, p. 4). The deontic justice perspective aims to describe why people care about fairness and why they react negatively to unfair treatment received by others (Cropanzano et al. 2003; Folger 2001). The deontic justice perspective evolved from fairness theory (Folger and Cropanzano 2001), which maintains that people react negatively to unfairness because of three things: an undesirable event or outcome has occurred, someone’s discretionary actions caused the outcome, and the actions violate moral principles. Deontic justice is based on the third tenet of fairness theory (Folger and Cropanzano 2001), which states that individuals react negatively to unfairness because this action violates moral principles. This includes “treating others as they should or deserve to be treated by adhering to standards of right and wrong” and involves “a judgment about the morality of the outcome, process, or interpersonal interaction” (Cropanzano et al. 2003, p. 1019; Folger 2001). Furthermore, deontic justice acknowledges that people care about justice because of the moral standard that all individuals should have the right to fair treatment (Cropanzano et al. 2003; Folger 2001). According to this, people take into account what is ethically and morally appropriate when they make decisions about fairness.

Drawing from deontic justice theory, we propose that the relationship between perceived discrimination against minorities and the perceived procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization should be amplified for people who are high in personal value for diversity compared to those who are low in personal value for diversity. People who value diversity and value having diverse groups of people at work are likely to react in a particularly negative manner to the mistreatment of minorities because, to them, it adds insult to injury. This is consistent with the deontic justice concept of moral accountability which emphasizes that “codes of conduct” should govern interpersonal relationships (Folger 2001, p. 14). This reasoning is also consistent with a theory of third-party reactions to the mistreatment of others which proposes that the observers’ individual personality traits will moderate reactions to observed mistreatment (Skarlicki and Kulik 2005). Related research shows that school leaders with high personal racial awareness of the problems that minorities face are more likely to blame an inhospitable school culture and less likely to blame minorities’ performance for minority faculty shortages (Buttner et al. 2007). Taken together, this suggests that individual values should modify the way that observers react to the mistreatment of minorities. Therefore, we offer the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

The negative relationship between perceived discrimination against minorities and the perceived procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization will be stronger for those with a high personal value for diversity than for those with a low personal value for diversity.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Employed participants were recruited from Master of Business Administration (MBA) classes and an upper division undergraduate business course at a large public university in the southern US. The study was conducted in two phases and used two different settings (i.e., paper-and-pencil and the Internet) to reduce the problem of common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003). In exchange for their participation, participants received extra credit. The Phase 1 survey was handed out in class along with postage paid envelopes addressed to the researchers. Perceived workplace discrimination against minorities, personal value for diversity, and demographic variables including sex, race, employment status, and work experience were collected during Phase 1. At this time we also collected the participants’ e-mail addresses. Participants had 15 days to complete the survey and mail it back to the researchers. After 15 days, the Phase 1 participants received an email with a web link to complete the Phase 2 survey. The Phase 2 web survey included the measure of procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization.

Of the 261 participants, 71 were removed (25 were not employed and 46 were either absent from class the day Phase 1 was administered or they did not answer the variables required for both phases of this study); 190 participants provided a full set of data and thus constituted the sample. To check for selection bias, we ran an ANOVA and χ2 tests to test whether participants who did not answer Phase 2 differed significantly on any variables of interest collected in Phase 1 and whether there were any demographic differences between those who answered Phase 1 only and those who answered both phases. Results showed no significant differences between groups based on sex or racial minority status. About half (51%) of the respondents were female. The majority of participants were Hispanic (78%), 9% were White, 6% were Asian, 1% were African American, and 6% were either “other” or bi-racial minorities. All participants were currently employed: 57% full-time and 43% part-time. Average age was 29 years. Mean full-time work experience was 8 years, and 58% of the participants were MBA students while 42% were undergraduate upperclassmen. The data presented in this study were collected as part of a larger data collection. However, except for the demographic variables, no variables overlap between this study and the other study from the same data set.

Phase 1 Measures

Participants were asked to think about their current employer and answer the questions.

Perceived Discrimination Against Minorities

We adapted one item from Hegarty and Dalton (1995): “My organization actively recruits members of traditionally underrepresented groups (females and minorities).” In addition, we wrote two items: “Members of traditionally underrepresented groups (females and minorities) are welcome in my organization” and “My organization strives to retain employees who are members of traditionally underrepresented groups.” All three items were reverse scored. Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed with each item on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Reliability was α = 0.77.

Personal Value for Diversity

We used the personal diversity value measure from Mor Barak et al.’s Diversity Perceptions Scale (1998). The items are: “Knowing more about cultural norms of diverse groups would help me be more effective in my job,” “I think that diverse viewpoints add value,” and “I believe diversity is a strategic business issue.” Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed with each item on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). The reliability for this scale was α = 0.70.

Control Variables

We controlled for participants’ minority status (coded as 0 = non-minority and 1 = minority) as well as sex (coded as 0 = male and 1 = female). As minorities and women have lower social status and tend to experience more discrimination than majority group members (Glick and Fiske 1996; Goldman et al. 2006; McKay et al. 2007; Sidanius and Pratto 1999), they may also perceive more procedural injustice.

Phase 2 Measures

Procedural Justice of Minorities’ Treatment by the Organization

Colquitt’s (2001) seven-item procedural justice measure was used. The items were modified to refer to procedural justice of minorities in the organization. One sample item was “Has your organization’s treatment of minority employees been free of bias?” Participants indicated the extent to which they agreed with each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = to a small extent to 5 = to a large extent). Reliability for this scale was α = 0.94.

Preliminary Analyses

We ran a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in LISREL (8.80) to establish the convergent and discriminant validity of our measures. A three-factor solution (perceived discrimination against minorities, personal value for diversity, and procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization) was a better fit (χ2 = 131.34, df = 51, CFI = 0.96, IFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.06; Kline 2005) than a two-factor solution combining discrimination against minorities and procedural justice of minorities onto the same factor (χ2 = 247.46, df = 53, CFI = 0.90, IFI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.10). A three-factor solution was also better than a one-factor solution (χ2 = 346.15, df = 54, CFI = 0.85, IFI = 0.85, SRMR = 0.13).

Results

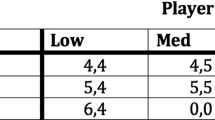

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations for all variables. We conducted a hierarchical multiple regression analysis to test Hypothesis 1. The variables in the interaction term were centered to test for moderation (Aiken and West 1991). The regression analysis consisted of three steps (see Table 2). In Step 1, the control variables, sex, and minority status, were entered. This step was not statistically significant (R 2 = 0.01). In Step 2, we added perceived workplace discrimination against minorities and personal value for diversity. The results of this step were significant (R 2 = 0.14; ∆R 2 = 0.13). In Step 3, we added the interaction between perceived workplace discrimination against minorities and personal value for diversity. The interaction term was significantly related to procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization and explained an additional 2% of the variance, which is common for interaction terms (McClelland and Judd 1993; R 2 = 0.16, ∆R 2 = 0.02). The interaction supporting Hypothesis 1 is shown in Fig. 1. The negative relationship between perceived discrimination against minorities and perceived procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization is stronger for those high in personal value for diversity.

General Discussion

Consistent with our predictions, the negative relationship between perceived discrimination against minorities and the reported procedural justice of minorities’ treatment by the organization is moderated by personal value for diversity. Those high in personal value for diversity react more negatively and rate the situation as being more procedurally unfair when they witness the mistreatment of women and minorities.

Implications for Theory and Practice

Theoretically, our findings support and extend the deontic justice perspective. People seem to recognize that discrimination against minorities is wrong because perceived discrimination against minorities is negatively and significantly related to the reported procedural justice of minorities. At the same time, the fact that we found moderating effects of personal value for diversity such that those who care the most about diversity react more intensely (Mor Barak et al. 1998), represents an extension to deontic justice. The deontic justice perspective should be extended to account for individual differences that lead some people to react more strongly to the mistreatment of minorities than others.

Our findings provide support for Skarlicki and Kulik’s (2005) theoretical model of third-party observers’ reactions to the mistreatment of others. These authors suggest that personality differences will moderate the extent to which observers will perceive injustice toward others. Our results support this theory within the context of mistreatment toward minorities and suggest that an important personality difference to be included in their theoretical model is the observer’s personal value for diversity.

These results are also consistent with other diversity research showing that when the members of diverse teams believe that diversity is good for teams and adds value, team identification is higher (van Dick et al. 2008; van Knippenberg et al. 2007). This study provides further evidence that an individual’s belief about the value of diversity is an important personal value that affects the way people perceive and react to their work environment.

A practical implication of this study is that by improving perceived procedural justice toward minorities, it may be possible to enhance the work experience for individuals with a high personal value for diversity. As there is a correlation between procedural justice toward others and one’s own procedural justice judgments (Colquitt 2004), and as one’s own perceptions of procedural justice are related to important individual outcomes, such as employee satisfaction, commitment, citizenship behavior, and job performance (Colquitt et al. 2001), it is possible that treating minorities well may improve the morale of others in the organization.

Also, our study suggests that because employees in organizations watch how others are being treated, it is important to understand which personal values may magnify the negative reactions that some employees have toward the poor treatment of others. This is consistent with research showing that when employees perceive discrimination in the organization in general (directed at themselves or at others), they are more likely to say that the organization has a deontic deficiency, meaning that it lacks integrity (Goldman et al. 2008). This implies that perceiving mistreatment toward minorities at work may damage the company’s reputation in the eyes of the observer employees, especially those with a high value for diversity.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

This study has several strengths. First, the sample of working adults answers calls for discrimination research utilizing employees drawn from real-world situations (Dipboye 1985; Dipboye and Colella 2005; Goldman et al. 2006), not imagined scenarios. The sample of mostly Hispanic employees also allows us to understand the perceptions of lower status group members (Sidanius and Pratto 1999). This is important because Hispanics are the largest minority group in the US (16.3% of the population in 2010; US Census Bureau 2011) and their representation is projected to grow to over 24% of the population by 2050 (US Census Bureau 2007). Another strength of our study design includes the data collection across two points in time which helps lessen common method variance, a problem common in discrimination research (Goldman et al. 2006).

However, our study also has several limitations. As we used a combined measure of discrimination against women and racial minorities, there is uncertainty about whether the participants were responding to sex, race, or both forms of discrimination. Future experimental research may be conducted to tease apart how participants respond to the sex and the race of the target person being discriminated against. It is also possible that the effect sizes in this study may be larger than they would be in the broader US population. As lower status group members are more likely to experience discrimination than are majority group members (Benokraitis and Feagin 1995; Feagin and Sikes 1994; McConahay 1983), the predominantly Hispanic sample may be especially attentive to the mistreatment of other minority group members. Future research may help tease out how minorities and non-minorities react to discrimination.

Another limitation of our study is that while our sample represents the largest minority group in the US. (i.e., Hispanics; US Census Bureau 2011), we cannot speak to other demographic minorities in the US. Our sample is fairly homogenous (78% Hispanic), which means that our results best generalize to Hispanics working in the US. Although our sample is not representative of the broader population, such non-representative samples can be valuable because they may shed light on sensitive subjects related to workplace discrimination (Goldman et al. 2006). Nonetheless, we acknowledge that other racial groups may respond differently to perceived discrimination against women and racial minorities. Future research may sample other demographic groups.

Future research may also explore predictors of personal values that trigger moral reactions to perceived discrimination. For example, is personal value for diversity driven by demographics, personal experience, or other factors? How are these beliefs formed, and what influence might organizations and their leaders have in shaping employees’ beliefs? It is possible that the more an organization argues for the “business case” in diversity, the more likely it is for employees to report strong value for diversity beliefs. Another possibility is that one’s work group may influence personal value for diversity. For example, if one’s work group is diverse and works well together, one may develop a stronger personal value for diversity. Future research may explore these predictors of personal value for diversity.

Conclusions

Based on the deontic justice perspective, we proposed and found that those with a high personal value for diversity react more strongly to perceived discrimination against women and racial minorities than those with a low personal value for diversity. Findings suggest that this is an important personal value that modifies the way observers make procedural justice judgments about the treatment of minorities in the workplace. Our results provide support for the deontic justice perspective which maintains that people look at what they personally judge to be right and wrong in making fairness decisions. Our results also suggest that in judging the procedural justice of others, it is important to take into account the observer’s personal value for diversity.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Boston: Beacon Press.

Benokraitis, N. V., & Feagin, J. R. (1995). Modern sexism: Blatant, subtle, and covert discrimination (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Buttner, H. E., Lowe, K. B., & Billings-Harris, L. (2007). Impact of leader racial attitude on ratings of causes and solutions for an employee of color shortage. Journal of Business Ethics, 72, 129–144.

Byrne, D. (1971). The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic Press.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 386–400.

Colquitt, J. A. (2004). Does the justice of the one interact with the justice of the many? Reactions to procedural justice in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 633–646.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

Cox, T. H., Jr. (1994). Cultural diversity in organizations: Theory, research and practice. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Cropanzano, R., Goldman, B., & Folger, R. (2003). Deontic justice: The role of moral principles in workplace fairness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 1019–1024.

Demuijnck, G. (2009). Non-discrimination in human resources management as a moral obligation. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 83–101.

Dipboye, R. L. (1985). Some neglected variables in research on unfair discrimination in appraisals. Academy of Management Review, 10, 116–127.

Dipboye, R. L., & Colella, A. (2005). Discrimination at work: The psychological and organizational bases. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2011). Charge statistics FY 1997 through FY 2010. http://eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/charges.cfm. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

Feagin, J. R., & Sikes, M. P. (1994). Living with racism: The black middle-class experience. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Folger, R. (2001). Fairness as deonance. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Research in social issues in management (pp. 3–31). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

Folger, R., & Konovsky, M. A. (1989). Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 115–130.

Folger, R., & Cropanzano, R. (2001). Fairness theory: Justice as accountability. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 1–55). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Folger, R., Cropanzano, R., & Goldman, B. (2005). What is the relationship between justice and morality? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 215–245). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 491–512.

Goldman, B., Gutek, B., Stein, J. H., & Lewis, K. (2006). Employment discrimination in organizations: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management, 32, 786–830.

Goldman, B. M., Slaughter, J. E., Schmit, M. J., Wiley, J. W., & Brooks, S. M. (2008). Perceptions of discrimination: A multiple needs model perspective. Journal of Management, 34, 952–977.

Hegarty, W. H., & Dalton, D. R. (1995). Development and psychometric properties of the organizational diversity inventory (ODI). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55, 1047–1052.

Hicks-Clarke, D., & Iles, P. (2000). Climate for diversity and its effects on career and organizational attitudes and perceptions. Personnel Review, 29, 324–345.

Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, 71, 589–617.

Kline, R. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Konovsky, M. A. (2000). Understanding procedural justice and its impact on business organizations. Journal of Management, 26, 489–511.

Kossek, E. E., & Zonia, S. C. (1993). Assessing diversity climate: A field study of reactions to employer efforts to promote diversity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14, 61–81.

Kray, L. J., & Lind, E. A. (2002). The injustices of others: Social reports and the integration of others’ experiences in organizational justice judgments. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 906–924.

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. Gergen, M. Greenberg, & R. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). New York: Plenum Press.

Leventhal, G. S., Karuza, J., & Fry, W. R. (1980). Beyond fairness: A theory of allocation preferences. In G. Mikula (Ed.), Justice and social interaction (pp. 167–218). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Lind, E. A., Kray, L. J., & Thompson, L. (1998). The social construction of injustice: Fairness judgments in response to own and others’ unfair treatment by authorities. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75, 1–22.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390.

McConahay, J. B. (1983). Modern racism and modern discrimination: The effects of race, racial attitudes, and context on simulated hiring decisions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9, 551–558.

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., Tonidandel, S., Morris, M. A., Hernandez, M., & Hebl, M. R. (2007). Racial differences in employee retention: Are diversity climate perceptions the key? Personnel Psychology, 60, 35–62.

Mor Barak, M. E., & Levin, A. (2002). Outside of the corporate mainstream and excluded from the work community: A study of diversity, job satisfaction, and well-being. Community, Work, and Family, 5, 133–157.

Mor Barak, M. E., Cherin, D., & Berkman, S. (1998). Organizational and personal dimensions in diversity climate. Journal of Applied Behavior Science, 34, 82–104.

Niehoff, B. P., & Moorman, R. H. (1993). Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 527–556.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 224–253.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Kulik, C. (2005). Third-party reactions to employee (mis)treatment: A justice perspective. Research in Organizational Behavior, 26, 183–229.

Stone-Romero, E. F., & Stone, D. L. (2005). How do organizational justice concepts relate to discrimination and prejudice? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 439–467). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Thibaut, J., & Walker, L. (1975). Procedural justice: A psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tomaskovic-Devey, D., Thomas, M., & Johnson, K. (2005). Race and the accumulation of human capital across the career: A theoretical model and fixed-effects application. American Journal of Sociology, 111, 58–89.

Triana, M., & García, M. F. (2009). Valuing diversity: A group-value approach to understanding the importance of organizational efforts to support diversity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 941–962.

Triana, M., García, M. F., & Colella, A. (2010). Managing diversity: How organizational efforts to support diversity moderate the effects of perceived racial discrimination on affective commitment. Personnel Psychology, 63, 817–843.

US Census Bureau. (2007). Hispanics in the US. http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hispanic/files/Internet_Hispanic_in_US_2006.ppt#1. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

US Census Bureau. (2008). 2008 National population projections. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

US Census Bureau. (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

Van den Bos, K., & Lind, E. A. (2001). The psychology of own versus others’ treatment: Self-oriented and other-oriented effects on perceptions of procedural justice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1324–1333.

van Dick, R., van Knippenberg, D., Hägele, S., Guillaume, Y. R. F., & Brodbeck, F. C. (2008). Group diversity and group identification: The moderating role of diversity beliefs. Human Relations, 61, 1463–1492.

van Knippenberg, D., Haslam, S. A., & Platow, M. J. (2007). Unity through diversity: Value-in-diversity beliefs, work group diversity, and group identification. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 11, 207–222.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Triana, M.C., Wagstaff, M.F. & Kim, K. That’s Not Fair! How Personal Value for Diversity Influences Reactions to the Perceived Discriminatory Treatment of Minorities. J Bus Ethics 111, 211–218 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1202-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1202-0