Abstract

This study examines the relationship between procedural justice and employee job insecurity, and the boundary conditions of this relationship. Drawing upon uncertainty management theory and ethical leadership research, we hypothesized that procedural justice is negatively related to job insecurity, and that this relationship is moderated by ethical leadership. We further predicted that the moderating relationship would be more pronounced among employees with a low power distance orientation. We tested our hypotheses using a sample of 381 workers in Macau and Southern China. The results support all of our hypotheses. The implications of these results for research and practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s rapidly changing organizational environment, job insecurity has become a near universal organizational phenomenon (Lee et al. 2006). Job insecurity is an employee’s perception of fundamental and involuntary change concerning the future existence of his or her present job in the employing organization (Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt 1984). Accumulated research has found evidence that job-insecure employees tend to react negatively in terms of work attitude, psychological well-being, and job performance (e.g., De Witte 1999; Sverke et al. 2002). These detrimental consequences suggest that there is a pressing need to understand the antecedents of job insecurity. However, the majority of research in this area focuses mainly on external factors, such as organizational change and national unemployment, or on personality traits, such as locus of control and negative affectivity (De Witte 2005; Lee et al. 2006). Little is known about whether employees’ evaluation of their organization’s adherence to moral and ethical standards influences job insecurity. As unethical conduct by an organization can trigger doubt among employees about the existing employer–employee relationship (Karnes 2009), workplace ethics are likely to be closely linked to employee job insecurity.

A primary ethical concern of employees is organizational justice. Being a fundamental value and virtue of organizations (Rawls 1971), justice is largely grounded in people’s ethical assumption about how human beings should be treated in the workplace (Folger et al. 2005; Skitka and Bauman 2008). Among the various dimensions of organizational justice, procedural justice, which refers to the perceived fairness of organizational processes and procedures that lead to decision outcomes, is a core and consistent predictor of employees’ reactions to their employing organization (Konovsky 2000). For instance, when employees perceive that organizational decisions are made through fair procedures, they report higher levels of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, trust in the organization, and job performance, and lower turnover intention (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001; Colquitt et al. 2001). The literature on psychological contract relates unfair procedures and job insecurity to the violation of the psychological contract between organization and employees (e.g., Robinson and Rousseau 1994). Interestingly, there has been little research (for an exception, see Blau et al. 2004) examining whether procedural justice shapes employees’ feelings of job insecurity.

This study aims to fill this research gap. Drawing on uncertainty management theory (Lind and Van den Bos 2002), we contend that procedural justice helps to reduce employees’ uncertainty about the continuity of their employment by enhancing their perception of predictability and controllability in their future as employees. We further propose that this relationship may be contingent on the combined effects of ethical leadership and employee power distance orientation. Defined by Brown et al. (2005, p. 120) as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making,” ethical leadership captures the dimensions of the leader both as a moral person and as a moral manager. Due to its emphasis on the morality of the manager (Avey et al. 2011), ethical leadership may alter the influence of procedural justice on job insecurity. This boundary condition may also depend on employee power distance orientation, which is an individual-level cultural value that is closely linked with employees’ reactions to leadership (Kirkman et al. 2009).

This study provides an answer to the research problem of whether fair procedures influence employees’ feeling of job insecurity and how this relationship alters under the combined contextual impact of ethical leadership and followers’ power distance orientation. By testing the three-way interaction effect of procedural justice, ethical leadership, and power distance orientation on job insecurity, this study addresses the dynamic influences of ethical practices in the workplace in general, and procedural justice and ethical leadership in particular, on employees’ feelings of job insecurity, a research area that is largely neglected in the literature on job insecurity. It also provides a more comprehensive analysis of the source of employee job insecurity by considering factors related to the organization (i.e., procedural justice), leaders (i.e., ethical leadership), and employees (i.e., power distance orientation). In the next section, we present the theoretical background to our hypothesized relationships.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

Procedural Justice and Job Insecurity

Although job insecurity has been defined in various ways (e.g., Davy et al. 1997; Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt 1984), the generally accepted underlying theme of the various definitions is that job insecurity is based on an employee’s own perception and interpretation of his or her immediate work environment. Thus, job insecurity is distinct from actual job loss, as two employees exposed to the same objective work environment may perceive the potential risk of job loss differently. Moreover, although the threat of job loss is likely to be particularly prevalent in the context of organizational downsizing, it also appears that job insecurity can emerge in seemingly unthreatened job situations (Sverke and Hellgren 2002). Due to these characteristics, job insecurity is an important issue that warrants careful consideration by all organizations.

In the psychological contract literature, maintaining long-term job security is considered to be one of the perceived core obligations of employers (Coyle-Shapiro 2002; Coyle-Shapiro and Conway 2005). According to this stream of research, job insecurity represents a violation of the psychological contract by the employer, and is negatively associated with employees’ organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and trust in their employer (e.g., Coyle-Shapiro and Kessler 2000; Robinson and Rousseau 1994).

De Witte (1999) suggested that job insecurity is harmful to employees because of its associated prolonged uncertainty. Two aspects of uncertainty have been identified: unpredictability and uncontrollability. Unpredictability refers to a lack of clarity about the future and about the expectation and behavior that an employee should adopt (De Witte 1999). When the likelihood of job continuity is not clear, employees may find it difficult to predict what will happen in the future and to choose the appropriate reaction. They may also feel powerless to control this potential threat. This sense of powerlessness, or uncontrollability, is suggested to be central to the phenomenon of job insecurity (Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt 1984). Powerlessness encompasses an employee’s inability to counteract the threat of job discontinuity (Ashford et al. 1989). According to Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt (1984), a sense of powerlessness is likely to arise when employees perceive that they have no inputs in decision making and no right of appeal, and that their organization has no strong norm of fairness. Sverke and Hellgren (2002) further postulated that the perception of fair treatment and participation in decision-making during change processes reduces the negative effects of stress induced by downsizing. In this research, we argue that procedural justice may be an effective means of coping with the unpredictability and uncontrollability inherent in job insecurity.

Uncertainty management theory (Lind and Van den Bos 2002) recognizes that fairness and uncertainty are closely linked in the sense that individuals tend to rely heavily on fairness information when they are confronted with uncertainty. According to this theory, people need predictability and tend to focus on environmental cues to reduce the uncertainties that arise in their lives, and fairness information is one of the most important cues. Employees look for fairness information to determine whether they are valued members of an organization (Tyler and Lind 1992), and use this information to guide how much they should identify with the organization to which they nominally belong (Lind 2001). Fairness information becomes particularly salient among those who experience a high level of uncertainty (Thau et al. 2007), because fairness reduces individuals’ anxiety about being excluded or exploited by the organization (Lind and Van den Bos 2002). Accordingly, fair treatment makes future events more predictable and controllable (Colquitt et al. 2006) and should help to reduce uncertainty about job continuity.

Four dimensions of justice are usually identified in justice research: distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational (Colquitt 2001). Of these, procedural justice is likely to have the most relevance to job insecurity. Unlike interpersonal justice and informational justice, which are more related to employee reactions toward supervisors (Loi et al. 2009b; Masterson et al. 2000), procedural justice connotes the structural features of an organization’s human resource decisions (Cropanzano et al. 2002) and reflects the extent to which the procedures in an organization regarding decisions are applied with consistency, accuracy, ethicality, correctability, representativeness, and bias-suppression (Leventhal 1980; Loi and Ngo 2010). Employees typically encounter procedural or process-relevant information before outcome-relevant information (Lind 2001), and are thus more likely to take procedural justice rather than distributive justice as a guide to reduce uncertainty related to their job.

Lind and Tyler (1988) posited that procedural justice signals to employees their status and standing within the organization. In particular, employees who perceive greater procedural justice will have a stronger sense that they are respected and valued members of the organization (Cropanzano et al. 2001), and thus should have less uncertainty about their organizational membership. In analyzing how survivors respond to organizational downsizing, Mishra and Spreitzer (1998) proposed that when the downsizing decision is based on fair procedures and rules, survivors are more likely to judge the downsizing in a more favorable light. A high level of procedural justice is desirable for survivors because it makes their future more predictable (Brockner et al. 2009). Thus, procedural justice can reduce adverse reactions to violations of the psychological contract by communicating to employees that they are still valued and important members of the organization (Robinson and Rousseau 1994; Rousseau 1995). The ability to express their views and feelings in the decision-making process enhances employees’ feelings of control (Colquitt 2001; Sverke and Hellgren 2002). Van den Bos (2001) empirically established that procedural justice has a stronger effect on employees’ emotional reactions when they feel uncertain or lack control. We thus anticipate that, with higher levels of procedural justice, employees tend to evaluate their job continuity to be more predictable and controllable, and will thus feel less insecure. Unfair procedures, in contrast, may lead employees to cast doubt on the security of their job. The following hypothesis is thus proposed.

Hypothesis 1

Procedural justice is negatively related to job insecurity.

Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership

As managers have legitimate power over employees and also control important organizational resources, they are in a unique position to mete out justice (Brown et al. 2005). More importantly, managers are often considered to be the core agents of the organization (Loi et al. 2009a), and their ethical leadership may strengthen employees’ view that procedural justice is an appropriate means of dealing with job insecurity (Lind 2001). Brown (2007) described an ethical leader as a captain piloting a ship in the right direction. Within organizations, employees usually look to their leaders for ethical guidance. Leaders’ personal and professional conduct in the workplace should thus serve as a model of normatively appropriate behavior (Brown et al. 2005). In terms of personal conduct, an ethical leader is a moral person who does the right thing. He or she is fair, honest, trustworthy, principled in decision-making, caring toward employees, and concerned about means rather than ends (Treviño and Brown 2007). In terms of professional conduct, an ethical leader is a moral manager who treats people correctly. He or she sets explicit ethical standards and expectations, proactively communicates these ethical standards and expectation to followers, and uses rewards and discipline to encourage followers to engage in ethical conduct (Treviño and Brown 2007). Thus, ethical leadership is suggested to help develop positive work attitudes among followers, such as dedication to the job and organizational commitment (Brown et al. 2005; Brown and Treviño 2006). Neubert et al. (2009) further proposed that ethical leadership behavior is primarily concerned with procedural justice in terms of listening and fair decision-making.

We contend that ethical leadership may moderate the relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity for two reasons. First, ethical managers perform in a fair, honest, and trustworthy manner. As a result, employees under their ethical leadership will perceive the organization’s procedures to be credible, and will have the confidence to rely on these procedures to reduce uncertainty about their job. In contrast, employees working under managers who exhibit unfair and dishonest behavior will perceive an inconsistency between the organization’s procedures and leadership behavior. They may then query whether the fair procedures in place are credible information that helps them to predict the future, and are less likely to rely on procedural justice to cope with uncertainty. Lin et al. (2009) further noted that when leaders have a strong sense of morality, procedural justice becomes important and consequential because employees use it to infer how they will be treated by the organization. Second, ethical leaders convey their ethical expectations to employees through open two-way communication (Brown et al. 2005). Their emphasis on adherence to organizational policies and practices should draw employees’ attention to the organization’s fair procedures, making procedural fairness sufficiently salient to stand out in the organizational context. Consequently, employees tend to believe that procedural justice is important in judging whether they can remain members of the organization. In contrast, managers who display poor ethical leadership avoid discussing fairness and ethics with their employees. Employees working under such managers are less likely to rely on procedural fairness to cope with job uncertainty. On the strength of this argument, we propose that ethical leadership may accentuate the negative relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity.

Hypothesis 2

Ethical leadership moderates the relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity such that the relationship is stronger under a high level of ethical leadership than under a low level of ethical leadership.

Employee Power Distance Orientation

Thus far, we have drawn largely on uncertainty management theory (Lind 2001) to hypothesize a negative relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity. We further propose that ethical leadership, due to its strong emphasis on fair procedures within the organization, may enhance this negative relationship. However, the extent of this moderating effect may depend on how employees react to their leaders’ values and behavior. One major individual characteristic that determines such reactions is employee power distance orientation (Hofstede and Hofstede 2005; Kirkman et al. 2009). Referring to the extent to which an individual accepts the unequal distribution of power in institutions and organizations (Farh et al. 2007), power distance orientation addresses the individual-level variation in cultural value relating to status, authority, and leadership behavior in organizations.

Employees with a higher power distance orientation value status differences and are more receptive to organizational hierarchy. They show strong respect and deference to the figures of authority in the organization (Hofstede and Hofstede 2005). In their eyes, leaders or managers are people of a different type (Hofstede 1980). They may think that copying the behavior of managers is inappropriate, and tend not to request information from high-ranking authority figures (Atwater et al. 2002). Thus, high-power-distance employees prefer to have less communication with and maintain greater social distance from managers (Farh et al. 2007). Low-power-distance employees, in contrast, are egalitarian and are less likely to submit to authority (Lam et al. 2002). They like to participate in organizational decision-making, and perceive managers to be socially close in terms of work experience and job responsibilities. Frequent and open communication with managers is preferred and expected (Kirkman et al. 2009).

Due to these differences in orientation, we propose that the moderating effect of ethical leadership on the relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity will be stronger among employees who have a low, rather than a high, power distance orientation. The promotion of ethical standards and two-way communications under ethical leadership fits well with the low power distance cultural values of participative decision-making and direct communication with superiors. Further, as low-power-distance employees stress power equality and do not value status differences, they tend to treat managers as similar others, which should facilitate the social learning process in the presence of ethical leadership (Brown et al. 2005; Salancik and Pfeffer 1978). The procedural fairness promoted by ethical managers is attractive to low-power-distance employees, as they use it as a way to satisfy their need for self-determination and control at work (Lam et al. 2002). Conversely, high-power-distance employees consider moral managers to be more distant figures within the organizational hierarchy. They prefer an autocratic management style (Bialas 2009), and are less likely to interpret and learn the ethical codes of their managers. Their avoidance of communication with superiors also attenuates the attention that they pay to the procedural justice highlighted by ethical leaders. This leads to the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3

There is a three-way interaction effect of procedural justice, ethical leadership, and power distance orientation on job insecurity. The moderating effect of ethical leadership on the negative relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity is strong among low-power-distance employees and weak among high-power-distance employees.

Method

Sample and Procedure

Survey data were collected in May 2010 from the employees of two garment manufacturing companies, one located in Macau and the other located in Zhuhai in mainland China. The cities are in the south of China and are close to each other. The two manufacturing facilities share the same ownership, and there are no notable differences between them in terms of leadership and production operation, thus justifying the merging of our data into a single sample. With the assistance of the human resources department of the two companies, we distributed a questionnaire to 196 employees at the Macau site and 283 employees at the Zhuhai site. The cover page of the questionnaire assured the respondents of their anonymity and the voluntary nature of the study. We received 381 completed and usable surveys, of which 149 were from Macau and 232 from Zhuhai, representing response rates of 76 and 82%, respectively. Among the respondents in the full sample, 76% were females, 44% were aged between 31 and 40, and 52% were pieceworkers. Their average tenure with the organization was 4.65 years.

Measures

The respondents rated items for all of the measures, except for the control variables, on a six-point Likert-type scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 6 = “strongly agree”).

Procedural Justice

We used Moorman’s (1991) seven-item scale to measure this construct. A sample item is “In my organization, procedures are designed to provide opportunities to appeal or challenge personnel decisions.” The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.88.

Ethical Leadership

We adopted the ten-item ethical leadership scale developed by Brown et al. (2005). A sample question is “My supervisor conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Power Distance Orientation

This construct was measured by seven items of the measurement scale used by Kirkman et al. (2009). One sample question is “In most situations, managers should make decisions without consulting their subordinates.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.65.

Job Insecurity

We used the five-item version of the job security scale of Kraimer et al. (2005) to measure job insecurity. A sample item is “My job will be there as long as I want it.” We reverse-coded all five items to measure job insecurity. The scale’s coefficient alpha in this study was 0.76.

Control Variables

Previous studies have suggested that job insecurity is related to employees’ demographic characteristics, such as gender, organizational tenure, and occupational group (e.g., Cheng and Chan 2008; De Witte 1999). We thus controlled gender, organizational tenure, and job type in our analysis. Gender was coded 0 for male respondents and 1 for female participants. Organizational tenure was measured by the number of years that the respondents had worked for the company. Job type was coded 0 for non-pieceworkers and 1 for pieceworkers. As our data were collected from two locations, we also controlled for firm (0 = Macau employees, 1 = Zhuhai employees) during the analysis.

Analytical Strategy

We tested our hypotheses using a series of hierarchical regression analyses. In testing the moderating role of ethical leadership and power distance orientation, we introduced interaction terms in the regression analyses in the manner suggested by Frazier et al. (2004). To avoid the problem of multicollinearity, we mean-centered the independent variable and the moderators before computing the interaction terms (Aiken and West 1991). In testing the two-way interaction effect, we entered procedural justice in the first step, ethical leadership in the second step, and finally the interaction term (i.e., procedural justice with ethical leadership) in the final step. A similar procedure was used to test the three-way interaction effect. We entered the independent variable and the two moderators in the first step, the three two-way interaction terms (i.e., procedural justice with ethical leadership, procedural justice with power distance orientation, and ethical leadership with power distance orientation) in the second step, and finally the three-way interaction term in the final step.

Results

To confirm the validity of the study constructs, we employed structural equation modeling estimated by maximum likelihood method to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using LISREL 8.71. The overall model fit was assessed by goodness-of-fit indices, including comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A reasonable model fit is indicated by CFI and IFI values of above 0.90 and RMSEA value of below 0.08. The four-factor measurement model had a model Chi-square of 1065.32 (P < 0.01) with 371 degrees of freedom (normed Chi-square coefficient: 2.87). The CFI was 0.91, the IFI was 0.91, and the RMSEA was 0.069. The model fit for a one-factor model (i.e., with all of the items loaded together on one factor) had a Chi-square of 2434.88 (P < 0.01) with 377 degrees of freedom (normed Chi-square coefficient: 6.46), CFI = 0.74, IFI = 0.75, and RMSEA = 0.15. A significant difference in Chi-square between the two models was noted (∆χ2(6) = 1369.56, P < 0.001). The CFA results thus suggest that the respondents were able to clearly distinguish the constructs under study.

The means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among the variables are shown in Table 1. Procedural justice is significantly related to job insecurity (r = −0.31, P < 0.01), which is consistent with our prediction. Ethical leadership is significantly related to both procedural justice (r = 0.33, P < 0.01) and job insecurity (r = −0.28, P < 0.01).

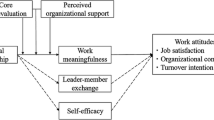

The hierarchical regression results for testing Hypotheses 1 and 2 are reported in Table 2. Model 1 includes only the control variables, whereas Model 2 includes also procedural justice. In support of Hypothesis 1, procedural justice is negatively related to job insecurity (β = −0.34; P < 0.01), as shown in Model 2 of Table 2. To test whether ethical leadership moderates this negative relationship, we entered the main effect of ethical leadership in Model 3 and the interaction term of procedural justice with ethical leadership in Model 4. Including this interaction term explains an additional 4% of the variance in job insecurity, and its coefficient is negative and significant (β = −0.19; P < 0.01). In showing this two-way interaction effect, we followed Aiken and West’s (1991) suggestion and plotted the slopes of procedural justice against job insecurity with a high ethical leadership (one standard deviation above the mean score of ethical leadership) and with a low ethical leadership (one standard deviation below the mean score of ethical leadership). Figure 1 clearly shows that the negative relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity is stronger under a high level of ethical leadership. This result supports Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 proposes a three-way interaction effect among procedural justice, ethical leadership, and power distance orientation on job insecurity. In analyzing the three-way interaction effect, we created three additional regression models, following the suggestion of Aiken and West (1991). Specifically, as shown in Table 3, we entered the main effect of power distance orientation in Model 5, the two-way interaction terms in Model 6, and the three-way interaction term in Model 7. The three-way interaction term included in Model 7 is positive and significant (β = 0.18, P < 0.05). We also followed Aiken and West’s (1991) suggestion in plotting the moderated relationship of procedural justice and ethical leadership on job insecurity at a high power distance orientation (one standard deviation above the mean score for power distance orientation) and a low power distance orientation (one standard deviation below the mean score for power distance orientation). Figure 2 presents this significant three-way interaction effect graphically. It shows that ethical leadership enhances the negative relationship between procedural justice and job insecurity for low-power-distance employees (Fig. 2a), but that this moderating effect does not exist for high-power-distance employees (Fig. 2b). Hypothesis 3 is thus supported.

Discussion

This study investigates whether an organization’s adherence to ethical standards can help employees to cope with job insecurity, a stream of research that remains largely unexplored in the current literature. Two ethical concerns in the workplace, procedural justice and ethical leadership, were examined. As predicted, we found that employees perceive less job insecurity when procedural justice is higher, and that ethical leadership further enhances this negative relationship. In addition, the interaction effect is more pronounced among employees with a low power distance orientation. Our findings have several important implications.

First, the results enhance our understanding of the antecedents of job insecurity among employees, and highlight how ethical practice in an organization plays a role in the development of employees’ sense of job insecurity. Our results show that employees rely on an organization’s fair procedures to judge their future. In situations of low procedural justice, employees feel their job continuity to be less predictable and controllable (De Witte 1999). The literature (Brockner 2010; Lind and Van den Bos 2002) suggests that when employees are uncertain about their standing as members of an organization, the effect of procedural justice on employee work outcomes is magnified. Our study extends this research and demonstrates that procedural justice has a direct impact on reducing job uncertainty. The results also echo Tyler and Lind’s (1992) relational model, which highlights the crucial role of procedural fairness when individuals are evaluating whether they are included or excluded in a collective group. Some justice scholars (Lind 2001; Van den Bos et al. 1997) have proposed the substitutability of the various dimensions of justice, and future research could investigate whether perceptions of other dimensions of justice, such as distributive, interpersonal, or informational justice, play a similar role to procedural justice in helping employees to cope with job insecurity.

Second, this study sheds new light on research into organizational justice and ethical leadership. The result for the two-way interaction effect provides empirical evidence that ethical leadership behavior can help organizations to apply fair procedures to help employees to deal with job insecurity. In addition to designing consistent, accurate, and bias-avoiding policies and procedures (Leventhal 1980), organizations also needs ethical agents to reinforce and execute these procedural rules. The existing literature usually focuses on the independent impact of fair procedures or ethical leadership on employee outcomes (e.g., Brown et al. 2005; Colquitt et al. 2001; Konovsky 2000; Mayer et al. 2009). Our study shows that ethical leadership can effectively assist leaders to promote the saliency of procedural fairness to employees. It is thus more fruitful for organizations to have both fair procedures and moral managers in place to cope with perceptions of job insecurity effectively.

Perhaps the most important set of results pertains to the three-way interaction effect among procedural justice, ethical leadership, and power distance orientation. Our results imply that, even if organizations find moral managers to execute and promote fair procedures, it is equally important to have a good match between leaders and followers. Compared with employees with a high power distance, low-power-distance employees, because of their perceived closeness to and similarity with their managers, are more attracted to the procedural justice promoted by ethical leaders. Brown and Treviño (2006) advised that future research on ethical leadership should closely examine the distance between leaders and followers, as it has a significant impact on how ethical leaders are perceived and the outcomes with which they are associated. This study answers this call and finds that followers’ power distance orientation appears to be a crucial boundary condition for the influence of effective ethical leadership. Future research should extend this line of enquiry by exploring the potential impact of other components of leader–follower distance, such as their distance in terms of the organizational hierarchy.

Managerial Implications

The findings of this study have important practical implications for organizations in addressing employee job insecurity. As job insecurity may not be an inherent consequence of downsizing or massive restructuring, but rather a subjective definition by employees (Sverke and Hellgren 2002), employers should ensure that fair procedures are in place at all times. Consistent and representative organizational policies that apply to all employees should be put in place at the establishment of the business. Further, as employees may have different expectations about work procedures due to changes in the economic environment, organizations are advised to revise written policies to better address their strategic direction and the changing needs of employees (Cropanzano and Byrne 2001). In all cases, adequate notice should be afforded to employees to maintain their sense that their job continuity is predictable and controllable.

The findings on the moderating effects of ethical leadership and power distance orientation also warrant additional managerial attention. As ethical managers are crucial in conveying the importance of procedural justice to employees, organizations should cultivate more ethical leadership behavior among their managers at all levels. More ethical leaders can be developed through selection and training. During the recruitment process, employers can signal to the job candidates that they value ethical leadership, which will attract applicants characterized by high moral intensity (Brown and Treviño 2006). Training that emphasizes moral reasoning and moral awareness is also necessary to facilitate the development of ethical leadership behavior.

As power distance orientation plays an important role in moderating the effect of ethical leadership, managers should be aware of the varying power distance orientation of their employees. For low-power-distance employees, invitations to engage in open communication and participation may be a better way of conveying the message that the organization uses fair procedures. Conversely, as high-power-distance employees tend to obey managers and follow orders without question, managers of such employees may need to exhibit a strong and benevolently paternalistic leadership style that directs their attention more strongly toward the importance of procedural justice (Aycan 2006; Kirkman et al. 2009).

Limitations and Conclusion

Like all studies, this research is not without its limitations. First, given the cross-sectional research design, any inference of causality among the variables must be accepted with caution. For example, it may be possible that job-insecure employees tend to perceive an organization’s procedures to be unfair. Future longitudinal research to determine the direction of causality is thus strongly recommended. Second, as our respondents provided self-reported ratings of the study variables, the results of this study may be tainted by common method variance. However, in the research design, we implemented procedural remedies such as assuring response anonymity and reminding our respondents that there was no right or wrong answer to the questions. Such procedures are known to reduce the threat of common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Moreover, the focus of the study is the interaction effect, which is less likely to be inflated by common method bias (Evans 1985; Lin et al. 2009; McClelland and Judd 1993). The results of our CFA also show that the respondents were able to clearly distinguish the constructs under study. Third, although we collected our data in different cities, the two companies were sister companies in the same industry, and all of the respondents were led by the same management group. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to other enterprises and cultural contexts. Future research could explore whether the relationships identified here can be applied in other industries and in a cross-cultural context. Finally, the alpha coefficient of power distance orientation in this study was only marginal at 0.65. However, this level of reliability is comparable with the alpha values reported in past studies (e.g., Begley et al. 2002; Dorfman and Howell 1988; Kirkman et al. 2009). Thus, our results are unlikely to be seriously affected.

To conclude, job insecurity is a key concern for employees nowadays. It is necessary for the management of modern organizations to overcome such negative feelings to maintain a healthy workplace. This research adds to our understanding of how procedural justice, coupled with ethical leadership, can help to reduce perceived job insecurity. It also highlights the importance of appropriately matching procedural justice and ethical leadership with the power distance orientation of employees. Extending the theory and results of this study to other organizational contexts is certainly warranted.

References

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Ashford, S. J., Lee, C., & Bobko, P. (1989). Content, causes, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 803–829.

Atwater, L., Wang, M., Smither, J. W., & Fleenor, J. W. (2002). Are cultural characteristics associated with the relationship between self and others’ ratings of leadership? Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 876–886.

Avey, J. B., Palanski, M. E., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2011). When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 98, 573–582.

Aycan, Z. (2006). Paternalism: Towards conceptual refinement and operationalization. In U. Kim, K. Yang, & K. Hwang (Eds.), Indigenous and cultural psychology (pp. 445–466). New York: Springer.

Begley, T., Lee, C., Fang, Y., & Li, J. (2002). Power distance as a moderator of the relationship between justice and employee outcomes in a sample of Chinese employees. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17, 692–711.

Bialas, S. (2009). Power distance as a determinant of relations between managers and employees in the enterprises with foreign capital. Journal of Intercultural Management, 1, 105–115.

Blau, G., Tatum, D. S., McCoy, K., Dobria, L., & Ward-Cook, K. (2004). Job loss, human capital job feature, and work condition job feature as distinct job insecurity constructs. Journal of Allied Health, 33, 31–41.

Brockner, J. (2010). A contemporary look at organizational justice. New York: Routledge.

Brockner, J., Wiesenfeld, B. M., & Diekmann, K. A. (2009). Towards a “fairer” conception of process fairness: Why, when, and how more may not always be better than less. Academy of Management Annals, 3, 183–216.

Brown, M. E. (2007). Misconceptions of ethical leadership: How to avoid potential pitfalls. Organizational Dynamics, 36, 140–155.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Cheng, G. H., & Chan, D. K. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 272–303.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 278–321.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 386–400.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425–445.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Judge, T. A., & Shaw, J. C. (2006). Justice and personality: Using integrative theories to drive moderators of justice effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100, 110–127.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M. (2002). A psychological contract perspective on organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 927–946.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Conway, N. (2005). Exchange relationships: examining psychological contracts and perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 774–781.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Kessler, I. (2000). Consequences of the psychological contract for the employment relationship: A large scale survey. Journal of Management Studies, 37, 903–930.

Cropanzano, R., & Byrne, Z. S. (2001). When it’s time to stop writing policies: An inquiry into procedural injustice. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 31–54.

Cropanzano, R., Prehar, C. A., & Chen, P. Y. (2002). Using social exchange theory to distinguish procedural from interactional justice. Group and Organization Management, 27, 324–351.

Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., Mohler, C. J., & Schminke, M. (2001). Three roads to organizational justice. In G. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 1–113). Oxford: Elsevier Science Limited.

Davy, J. A., Kinicki, A. J., & Scheck, C. L. (1997). A test of job security’s direct and mediated effects on withdrawal cognitions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 323–349.

De Witte, H. (1999). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8, 155–177.

De Witte, H. (2005). Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31, 1–6.

Dorfman, P. W., & Howell, J. P. (1988). Dimensions of national culture and effective leadership patterns: Hofstede revisited. Advances in International Comparative Management, 3, 127–150.

Evans, M. G. (1985). A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 305–323.

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcomes relationships in china: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 715–729.

Folger, R., Cropanzano, R., & Goldman, B. (2005). What is the relationship between justice and morality? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 215–245). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. D., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 115–134.

Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 3, 438–448.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Karnes, R. E. (2009). A change in business ethics: The impact on employer-employee relations. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 189–197.

Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J., Chen, Z. X., & Lowe, K. B. (2009). Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leadership: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 744–764.

Konovsky, M. A. (2000). Understanding procedural justice and its impact on business organization. Journal of Management, 26, 489–511.

Kraimer, M. L., Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2005). The role of job security in understanding the relationship between employees’ perceptions of temporary workers and employees’ performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 389–398.

Lam, S. S. K., Schaubroeck, J., & Aryee, S. (2002). Relationship between organizational justice and employee work outcomes: A cross-national study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 1–18.

Lee, C., Bobko, P., & Chen, Z. X. (2006). Investigation of multidimensional model of job insecurity in China and the USA. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 55, 512–540.

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. S. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27–55). New York: Plenum.

Lin, X. W., Che, H. S., & Leung, K. (2009). The role of leader morality in the interaction effect of procedural justice and outcome favorability. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 1536–1561.

Lind, E. A. (2001). Fairness Heuristic theory: Justice judgements as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 56–88). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural Justice. New York: Plenum.

Lind, E. A., & Van den Bos, K. (2002). When fairness works: Toward a general theory of uncertainty management. In B. M. Staw & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 24, pp. 181–223). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Loi, R., Mao, Y., & Ngo, H. Y. (2009a). Linking leader-member exchange and employee work outcomes: The mediating role of organizational social and economic exchange. Management and Organization Review, 5, 401–422.

Loi, R., & Ngo, H. Y. (2010). Mobility norms, risk aversion, and career satisfaction of Chinese employees. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 27, 237–255.

Loi, R., Yang, J., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2009b). Four-factor justice and daily job satisfaction: A multilevel investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 770–781.

Masterson, S. S., Goldman, B. M., & Taylor, M. S. (2000). Integrating justice and social exchange: The differing effects of fair procedures and treatment on work relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 738–748.

Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. (2009). How does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 1–13.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390.

Mishra, A. K., & Spreitzer, G. M. (1998). Explaining how survivors respond to downsizing: The roles of trust, empowerment, justice, and work redesign. Academy of Management Review, 23, 567–588.

Moorman, R. H. (1991). Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 845–855.

Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 157–170.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 245–259.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 224–253.

Skitka, L., & Bauman, C. W. (2008). Is morality always an organizational good? In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Justice, morality, and social responsibility (pp. 1–28). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Sverke, M., & Hellgren, J. (2002). The nature of job insecurity: Understanding employment uncertainty on the brink of a new millennium. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 23–42.

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A Meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 242–264.

Thau, S., Aquino, K., & Wittek, R. (2007). An extension of uncertainty management theory to the self: The relationship between justice, social comparison orientation, and antisocial work behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 250–258.

Treviño, L. K., & Brown, M. E. (2007). Ethical Leadership: A Developing Construct. In D. L. Nelson & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Positive organizational behavior (pp. 101–116). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 115–191). New York: Academic Press.

Van den Bos, K. (2001). Uncertainty management: The influence of uncertainty salience on reactions to perceived procedural fairness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 931–941.

Van den Bos, K., Vermunt, R., & Wilke, H. A. M. (1997). Procedural and distributive justice: What is fair depends more on what comes first than on what comes next. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 95–104.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Loi, R., Lam, L.W. & Chan, K.W. Coping with Job Insecurity: The Role of Procedural Justice, Ethical Leadership and Power Distance Orientation. J Bus Ethics 108, 361–372 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1095-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1095-3