Abstract

Scandals in companies such as Enron have been a source of great concern in the last decade. The events that led to a global financial crisis in 2008 have heightened this concern. How does one account for executive behaviors that led to such a crisis? This article argues that a conjunction of motive, means, and opportunity creates ‘an ethical hazard’ making questionable executive decisions more probable. It then suggests that corporate unethical behavior can be minimized by creating a process to identify and remove such ethical hazards, and by appointing an ‘ethical hazards marshal.’

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Financial scandals in companies such as Enron and WorldCom in the past two decades raised some important and troubling questions about leadership and how leaders influence organizational decisions. Top executives at these and many other companies were eventually convicted of crimes and given lengthy jail sentences. Such executive behavior, in some cases from graduates of business schools, caused much soul-searching in the academic world. It was argued by many that these cases demonstrated the need for the teaching of ethics in business schools in order to prevent a recurrence of such behavior by future corporate leaders (Gioia 2002; AACSB 2007; Beggs and Lund Dean 2007; Halbesleben et al. 2005). The concern about business ethics on the part of business school graduates also led to student initiatives such as the ‘Harvard MBA Oath’ (Moreira and Petersmeyer 2009).

The damage caused by the financial scandals in these companies was restricted mostly to the companies where the scandals occurred and their stakeholders. The financial crisis of 2008, on the other hand, has had a far wider impact—involving banks, insurance companies, brokerage houses, hedge, mutual and pension funds, and many ordinary investors. Further, the impact was not restricted only to the US but extended to financial institutions in many countries in Asia, Europe, and North and South America, along with the millions of home-owners who faced foreclosures on their mortgages (Davis 2009). The effects of the 2008 financial crisis also influenced the 2010 US Congressional elections as well as the 2011 credit rating downgrades for countries ranging from Greece to the US.

The financial crisis was by no means totally unforeseen or unpredictable. In his Berkshire Hathaway annual report of 2002, Warren Buffett had warned of the consequences of the increasing leverage and the growing market in derivatives: “The derivatives genie is now well out of the bottle, and these instruments will almost certainly multiply in variety and number until some event makes their toxicity clear… In our view, derivatives are financial weapons of mass destruction, carrying dangers that, while now latent, are potentially lethal” (Buffett 2002, p. 16).

Why did the executives involved in these fateful decisions act the way they did? Was their behavior criminal, as implied by the investigations by the FBI (BBC 2008)? Was it based on greed and lack of social conscience, as Senator Jim Bunning and others in Congress have argued (Barrett et al. 2008)? Was it merely the result of pursuing normal business practices that happened to go wrong? These and similar questions lead to the more general question about how we can understand the conditions under which some people engage in unethical behavior.

Understanding Behavior: Internal and External Approaches

There has been a long-standing debate among philosophers and psychologists (among other scholars) as to what causes people to act the way they do, and how to influence their behavior. In their review of the literature on this question, Beggs and Lund Dean (2007, p. 15) suggest that the debate can be categorized in terms of those who believe in ‘internal forces’ such as a person’s parental upbringing, education, and personality as the primary causes of their behavior, and others who believe that behavior is primarily affected by ‘external forces’ that operate on the person.

In the first view, to influence someone’s behavior, one must change the person, primarily through education. Beggs and Lund Dean cite Immanuel Kant as an exponent of the first view, as someone who believed in the ability of education to produce change: “[N]othing other than structured, disciplined and repeated moral training could produce responsible citizens oriented toward ‘the good’” (Beggs and Lund Dean 2007, p. 17).

In the second view, to change a person’s behavior one must attempt to change the situational forces operating on that person. An example of this view is Devinney’s argument (2009, p. 54) that “organizations are social contexts, and we know from experiments such as the Stanford prison experiment (Zimbardo 2007) that we can influence the revealed good and bad characteristics of individuals by manipulating the context and expectations in which their actions are embedded.”

It is of course possible to combine these two views about behavior in various ways. For example, when explaining why some authors commit violations of ethical practices when submitting papers to the Academy’s journals, Schminke, Chair of the Academy of Management’s Ethics Education Committee (2009, p. 587) writes “Although most Academy members embrace the highest possible ethical principles, some are simply unaware of the specific ethical standards they are expected to uphold as members of the Academy. Still others are aware of these standards but choose not to uphold them.” Similarly Trevino (1986, p. 601) combines the two views in what she describes as the ‘Interactionist’ model which “combines individual variables … with situational variables to explain and predict the ethical decision-making behavior of individuals in organizations.”

In their policies on teaching ethics, business schools appear to have adopted the first view—consistent with Kant’s approach to influencing behavior toward ‘the good.’ Ghoshal (2005, p. 75) writes: “The corporate scandals in the United States have stimulated a frenzy of activities in business schools around the world. Deans are extolling how much their curricula focus on business ethics.” A survey by Christensen et al. (2007) revealed that there has been a 500% increase in ethics courses offered at the Financial Times Top 50 Global Business Schools since 1988. Similarly, Aspen Institute (2010) publishes a survey titled Beyond Grey Pinstripes every 2 years showing the ranking of the top 100 business schools in the world in terms of their commitment to teaching ethics-related courses. On the other hand, Gioia (2002) expresses concern that many schools are shirking from the responsibility of including adequate ethics material in their courses. Business is not the only field to have added ethics courses to the curriculum. Other professions such as law (Lerner 2006) and accounting (Verschoor 2006) have also moved to add ethics-related courses in their programs.

A Brief Review of the Literature

As noted by Kish-Gephart et al. (2010, p. 1) until recently ethics used to be seen by many as the ‘province of philosophers.’ Trevino and Brown (2004, p. 77) point out that ethical scandals are not a new phenomenon; in fact “unethical conduct has been with us as long as human beings have been on the earth.” They note that the Talmud, for example, includes 613 direct commandments to guide Jewish conduct. What is new is the extent to which management and organizational scholars have carried out empirical studies over the last 30 years to determine why individuals sometimes behave unethically in the workplace.

Important among these are studies by Trevino and her colleagues (Trevino 1986; Trevino and Youngblood 1990; Trevino and Brown 2004; Trevino et al. 2006; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010) as well as those by Baucus and Beck-Dudley (2005), Baucus et al. (2008), Palmer and Maher (2006), and Pinto et al. (2008).

It would be difficult to adequately review the wealth of studies on this topic. Fortunately, it is not necessary to do so in great detail because Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) have recently published a meta-analysis of 136 studies covering a total of 43,914 people. They define unethical behavior as “any organizational member action that violates widely accepted (societal) moral norms” (p. 2). They add that “unethical behaviors overlap with illegal behaviors. This relationship between ethics and the law can be represented as a Venn diagram … wherein the overlapping area of the two circles represents behaviors [such as stealing] that are both illegal and unethical” (p. 2). This is a useful point for the purpose of this article since some of the examples of behaviors discussed below combine unethical and illegal aspects of behaviors.

Trevino and Youngblood (1990) specify a model with unethical behavior as the dependent variable and ‘bad apples’ and ‘bad barrels’ as the independent variables. They describe the relationship between ‘bad apples’ and ‘bad barrels’ as follows: “The ‘bad apples’ argument attributes unethical behavior in the organization to a few unsavory individuals … lacking in some personal quality such as moral character … According to the ‘bad barrels’ argument, something in the organizational environment poisons otherwise good apples” (Trevino and Youngblood 1990, p. 378). Their ‘bad apples’ and ‘bad barrels’ variables are similar to the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ approaches to behavior mentioned above. The notion of ‘bad barrels’ has some similarities to the concept of ‘criminogenic’ organizations (Needleman and Needleman 1979). Criminogenic organizations are defined as those “that produce or tend to produce crime or criminal behavior” (Pinto et al. 2008, pp. 685–686). This concept will be discussed further in a later section.

In their meta-analysis, Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) add a third independent variable termed ‘cases.’ “[T]he term case, with its context-sensitive connotation, aptly conveys the idea that moral issue characteristics vary by the specific circumstances being faced at the time (along with the symbolic meaning of case as a smaller, more proximal container than barrels for individual apples)” (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010, p. 2).

The key conclusions of the Kish-Gephart et al. (2010, pp. 12–13) meta-analysis can be summarized as shown in Fig. 1.

Comparing Individual and Organizational Factors that Influence Unethical Behavior

An important question that follows from the Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) meta-analysis is whether we can quantify the influence of each of the three types of variables in determining the extent of unethical behavior in an organization. Unfortunately the answer to this question is ‘No.’ As Kish-Gephart et al. (2010, pp. 14–15) report, they could not offer a meta-analytic answer to this question because there have been very few empirical studies that collected data regarding more than one set of independent variables simultaneously.

The Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) analysis does include several studies which show that organizational factors play a significant role in determining whether unethical behavior takes place in a work setting. For example, Trevino (1986, p. 608) indicates that a “large majority of managers reason about work-related ethical dilemmas at the conventional stages (levels 3 and 4)” of cognitive moral development (CMD) (Kohlberg 1969) and therefore these “managers will be most susceptible to situational influences on ethical/unethical behavior” (Trevino 1986, p. 610).

A review by Trevino et al. (2006, p. 956) summarizes studies showing that accounting students and managers in public accounting had, on average, lower moral reasoning scores than their counterparts in other schools or professions, and that older and longer tenured managers had lower average scores than younger and less experienced employees. Ashkanasy et al. (2006) report that the CMD level in their MBA student sample was slightly below the adult CMD norm. Finally, Gioia (2002) cites evidence that students at 13 eminent business schools had lower ethical scores by their graduation compared to the scores they had when they began their studies.

Similarly Trevino and Brown (2004, p. 72) argue that “most people are the product of the context they find themselves in … They look outside themselves for guidance when thinking about what is right” and note that nearly two-thirds of normal adults agreed to “harm another human being” when asked to do so in Milgram’s (1974) obedience to authority experiment. Further support for the argument that situational factors play a significant role in determining the extent of unethical behavior is offered by several other studies such as Rotter (1966), Pinto et al. (2008), Baucus and Beck-Dudley (2005), and Ashforth and Anand (2003). Trevino also points out that situational factors are likely to play a particularly significant role in real life, because situational clues are more salient in real life than in hypothetical dilemmas typically used in laboratory studies to measure one’s level of cognitive moral development (Trevino 1986, p. 608).

Table 1 summarizes the implications for reducing unethical behavior derived from the Kish-Gephart model shown in Fig. 1. The implications for reinforcement, the remaining antecedent, are discussed in the sections that follow.

Reinforcement as a Situational Variable

One of the key situational/organizational factors that significantly influence ethical behavior is the reinforcement (or lack of reinforcement) for previous ethical behavior. Though not included in the Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) meta-analysis, reinforcement was one of the variables in the Interactionist model initially developed by Trevino (1986, p. 603). It is also included as a variable by Hegarty and Sims Jr. (1979), Trevino and Youngblood (1990), Trevino et al. (2006), and Ashkanasy et al. (2006). These studies found that reinforcement has an impact on ethical behavior under certain conditions. Hegarty and Sims Jr. (1979) found that when unethical behavior resulted in higher profits, such behavior was more likely to take place, and Trevino and Youngblood (1990, pp. 383–384) found that punishment which was expected or mild did not reduce unethical behavior by the subjects in their experiment: the subjects were influenced only if the reinforcement was ‘unexpected and powerful.’

The finding that reinforcement influences behavior under certain conditions is consistent with numerous other studies by psychologists, game theorists, and economists. A full discussion of the literature in these fields is beyond the scope of this article but relevant key examples of this research will be noted briefly.

Psychological Research

Reinforcement Theory

The central notion behind reinforcement theory is that behavior is governed by its (expected) consequences (Skinner 1969), and therefore the best way to modify behavior is to redesign the situation so that people are reinforced for the desired behavior. The reinforcement structure in a situation can be so powerful that if reinforcement is unwittingly given for undesired behavior, such undesirable behavior will occur even if individuals know that they should behave differently. This phenomenon is discussed with numerous examples in the classic article “On the folly of rewarding A while hoping for B” (Kerr 1975, 1995).

Attribution Theory

This theory suggests that our understanding of the reasons behind someone’s behavior should focus on the ‘situational’ factors facing the individual rather than the ‘dispositional’ (i.e., internal or personality-related) factors. According to ‘the fundamental attribution error’, a key concept of attribution theory, we tend to overemphasize dispositional factors and underemphasize situational factors when trying to understand the reasons for someone’s behavior. Thus, insofar as the behavior is correctly attributable to the situational factors, we are more likely to be successful in changing that behavior if and when we can change the situation (Ross and Fletcher 1985; Epley and Dunning 2000).

A practical application consistent with attribution theory is Ralph Nader’s work in the 1960s and 1970s. Companies such as General Motors at the time blamed the ‘nut behind the wheel’ as the cause of road accidents and advocated better driver training as the solution. Nader (1965) argued that, on the other hand, accidents are caused by cars that are ‘Unsafe at Any Speed’ because the dangers are designed-in in the car, and that this is true for the construction of highways as well. Many improvements in highway design and car design (seatbelts and airbags being two prominent examples) have considerably reduced highway accidents and fatalities since the 1970s.

Conformity and Decision Making

Classic experiments such as those by Asch (1958), Milgram (1974), Zimbardo et al. (1973), and Janice (1982) show how much impact situational factors, whether from peer pressure or pressure from authority figures, can have on an individual’s behavior.

Game Theory Research

A field straddling psychology and economics, game theory focuses on the types of co-operative or competitive behaviors the members of a dyad are likely to engage in under different payoff and communication conditions. The results of experimental research utilizing a game theory framework are broadly consistent with both the psychological and economic theories of behavior. They show that as long as the nature of the payoff matrix in a game such as the ‘Prisoners’ Dilemma’ encourages defection rather than co-operation among the players, the players will continue to defect, even when they know that they would each fare better if only they could trust each other. Furthermore, the defections continue even after the two parties have been given ample opportunity to communicate with each other about the desirability of co-operation. Co-operative behavior occurs only when the payoff conditions or some other element regarding the structure of the game has been changed to make co-operation the rational choice for the players. Pajunen (2006) offers a recent review of this literature.

Economic Research

A key assumption in economic theory is that of the ‘economic man’ whose behavior is motivated by incentives, usually of a monetary nature (Cadsby et al. 2007). Adam Smith (1776, p. 700; Kotowitz 1987, p. 549), in his classic work explained the relationship between unethical behavior and incentives:

The directors of such companies, however, being the managers rather of other peoples’ money than of their own, it cannot well be expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery [i.e., partnership] frequently watch over their own … Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company.

Coffee Jr. (2005) reviews a number of statistical studies that analyze data submitted by corporations to agencies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission. These studies offer empirical support to the comment made by Adam Smith and indicate specific conditions under which different types of unethical behavior are likely to take place. In particular, these studies show that unethical behavior takes two different forms depending on ownership structure and types of incentives offered:

-

When share ownership in a company is widely dispersed, and where the CEO’s compensation is largely dependent on stock options, fraud tends to take place by means of ‘earnings management’, usually by revenue recognition manipulation. Furthermore, as the quantity of options granted increases, the likelihood of fraud also increases. The use of ‘earnings management’ implicated in many scandals is commonly related to the availability of stock options, which are typically granted only to very senior managers. This is one of the reasons that large-scale abuse seen in companies such as Enron, Tyco or WorldCom took place at the highest levels of management.

-

Fraud based on ‘earnings management’ is less likely to take place in companies in which the ownership or control is concentrated in a few individuals (or a family). Instead, the unethical behavior here occurs with controlling shareholders attempting to expropriate assets from minority shareholders. Shares with multiple voting rights are often used in these companies as the means to ensure that the founders maintain control of the company even when their shareholdings would not give them a majority ownership. Hollinger provides an example of a company in which the controlling shareholders enriched themselves at the expense of other shareholders without having to resort to earnings management. Instead, they managed to profit by selling company assets and using the money from the assets to reward themselves for a so-called non-compete provision (St. Eve 2007).

-

Coffee’s (2005) research thus indicates that it is possible to predict with some confidence the conditions under which managers are likely to engage in unethical behavior, and also the form it is likely to take. The corollary is that if it is possible to take preventive actions to change these conditions, this will make it less likely that executives will engage in unethical behavior.

Thus, the common theme in the psychological, game theory, and economic research summarized above is that situational factors, particularly the reinforcement provided by the situation, influence behavior—either for good or ill.

The Concept of an Ethical Hazard

As Kish-Gephart et al. (2010, p. 2) have noted, there is often an overlap between unethical behavior and illegal behavior in organizations, with corruption and fraud, for example, being both unethical and illegal. The examples of Enron and Hollinger described above, along with similar examples from many other companies, illustrate behavior that is both illegal and unethical. Thus, we can productively apply certain concepts from criminal behavior to understanding unethical as well as illegal behavior of the sort illustrated here (Needleman and Needleman 1979; Ashforth and Anand 2003; Palmer and Maher 2006; Pinto et al. 2008).

One of these concepts from criminal law is that the person who committed a crime is likely to be a person who had a motive, means, and opportunity (MMO) to do so. Utilizing the concept of a criminogenic organization (Needleman and Needleman 1979), some scholars have referred to some parts of the MMO formulation in their studies of organizations that encourage or facilitate criminal behavior. Thus, Pinto et al. (2008, p. 700) argue that “For the OCI [organization of corrupt individuals] phenomenon to occur, there must be an opportunity and a motivation to engage in corruption.” Similarly, McKendall and Wagner (1997) conclude that organizational crime (in the context of environmental law violations) is the product of motive, opportunity, and choice.

It is a well established principle in criminal law, however, that the fact that a person had MMO to commit a crime does not necessarily prove beyond reasonable doubt that the person in fact did commit the crime (Commonwealth vs. Michael M. O’Laughlin 2005). Extending this concept to unethical behavior we can say that the conjunction of MMO creates an ‘ethical hazard’: it increases the likelihood of unethical behavior but does not necessarily guarantee that it will occur.

The term ‘ethical hazard’ is related to ‘moral hazard,’ a term widely used by economists. ‘Moral hazard’ has a highly technical meaning in economics, having to do, in part, with ‘uncertainty and incomplete or restricted contracts (Kotowitz 1987, p. 549). ‘Ethical hazard’ as used here is a broader term, and does not rely on uncertainty or incomplete or restricted contracts, but rather refers to a situation that is likely to increase the probability of unethical behavior because of a conjunction of motive, opportunity and means to engage in such behavior.

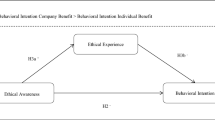

Figure 2 shows this relationship between MMO, with an ‘ethical hazard’ being created when all three factors co-exist.

The Role of MMO in Creating Ethical Hazards

Motive

A motive can be defined as ‘a person’s reason for choosing one behavior from among several choices’ (Moorhead and Griffin 1998, p. 120). There are many theories of motivation, among which expectancy theory (Vroom 1964) has been particularly influential. According to expectancy theory (as revised by Van Eerde and Thierry (1996), based on the evidence from their meta-analysis) a person given a choice among outcomes A, B, C … N will make a choice based on two considerations: (a) the probability of achieving an outcome K and (b) the value of outcome K.

Multiplying these two components, probability and value, gives the ‘expected value’ for each outcome and a person will make a choice that will maximize his or her expected value.

Steel and Konig (2006) have suggested that expectancy theory can be integrated with three other related theories of motivation to achieve greater comprehensiveness:

-

1.

Time preference or Picoeconomics: People place a higher value on outcomes that happen in the near future than on outcomes to be obtained in distant future (Ainslie 1992).

-

2.

Cumulative Prospect Theory: (a) People tend to be risk averse—they place a higher negative value on a loss of a particular amount than on the positive value of the gain of a similar amount (Tversky and Kahneman 1992) and (b) People have difficulty in accurately estimating probabilities of various outcomes. They tend to overestimate the probability of relatively rare outcomes (‘long shots’ such as winning a multi-million dollar lottery) and underestimate the probability of relatively likely outcomes (Tversky and Kahneman 1992).

-

3.

Individual Differences: Different people place different values on the same outcome, based on their need structure such as the levels of their need for Achievement, need for Affiliation or need for Power (McClelland 1985). This is akin to the “Individual Characteristics” component of the Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) model. According to their model those with a low level of cognitive moral development and a high level of Machiavellianism are more likely to be willing to use unethical methods such as earnings manipulation to gain a monetary benefit. People also differ in the extent to which they display preference for an immediate reward as against a delayed reward, and the extent to which they are risk averse or make poor estimates of probabilities (Steel and Konig 2006).

These factors relating to motivation can be used to explain, for example, why stock options create a high level of motivation among managers in companies such as Enron (Ackman 2002; Samuelson 2002), and Nortel (Evans 2007).

-

(a)

The stock options had a very high monetary value to the managers. For example, by the end of 2000, Enron had issued options to its managers enabling them to buy up to 47 million shares at a price of $30. At the time, Enron shares were selling for about $83, offering a potential profit per share of $43, and for a total potential profit of over $2 billion (Samuelson 2002).

-

(b)

There was not much risk of loss involved in accepting stock options. If the price of shares had declined below $30, Enron executives would not have lost any of their own money since they had not paid for the options anyway, and they still had their regular income from salary and bonuses. So risk aversion was not an important factor.

-

(c)

The options were vested immediately, that is they could be sold as soon as they were granted. Thus, the reward arrived quickly rather than after a long wait (provided the market price remained higher than the issuing price). This immediacy of the reward made the stock options even more motivating.

Means

The term ‘means’ refers to the instrument(s) available to a person to carry out a task. In a criminal case, for example, a gun may be the instrument the alleged criminal used to murder his victim. In corporate crimes or unethical behavior, the means are usually not physical objects but a source of power that gives the executive the ability to behave unethically.

Abuse of stock options serves as a good example. To be able to abuse stock options, an executive must be able to artificially raise the price of the company’s shares, at least for a short period. The price of shares normally increases when the reported earnings increase, so the executive must be able to manipulate the reported company earnings through revenue recognition and other techniques described in the next section. Executives typically gain an ability to manipulate reported earnings from two sources:

-

(a)

Weak Corporate Governance: Corporate governance procedures are designed, in part, to control the power available to top management. Studies on corporate governance indicate, however, that the board of directors, entrusted with the responsibility to control the CEO’s power often becomes instead a rubber stamp controlled by the CEO. The extensive literature on the problems faced by directors attempting to control top management is reviewed in Dalton et al. (2007). These problems can occur even when the directors include (as in the case of Hollinger) such eminent individuals as former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and former Governor of Illinois, James Thompson (U.S. District Attorney 2007).

As Lord Acton’s famous dictum states, ‘Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ (Acton 1887). The near-absolute power enjoyed by the CEO and others provides the means for them to engage in unethical and/or illegal behavior. Thus, chief executives at Tyco, Hollinger, and Parmalat were able to charge millions of dollars of personal expenses to their companies, or charge millions of dollars in inflated fees to provide services from other companies that they controlled.

-

(b)

Access to the Power of External Agents: External agents can also add to the power available to the CEO and other top managers. For example, the fact that Enron’s external auditors, Arthur Andersen, had a consulting contract in conflict with their role as auditors made the task of bending the usual definitions that much easier for Enron executives. The offering of such a contract was, in turn, in the hands of the top management.

Similarly, several external financial analysts worked together with some CEOs to inflate stock prices, at least in the short run. Thus, Jack Grubman, former Salomon Smith Barney’s telecommunication analyst, helped WorldCom CEO Bernie Ebbers to ‘hype’ WorldCom’s stock price. Salomon Smith Barney in turn hoped to gain investment banking business from Ebbers (Moberg and Romar 2003).

Henry Blodget played a similar role at Merrill Lynch. According to the e-mails obtained by the New York Attorney General, Mr. Blodget once threatened to “start calling stocks as he sees them ‘no matter what the ancillary business consequences’” unless Merrill Lynch agreed to pay him a substantial bonus. Merrill Lynch’s investment banking business was dependent on the goodwill of large companies whose shares were being (unjustifiably) promoted by Blodget. The threat worked and the bonus was paid (Morton 2004, p. FP5).

Opportunity

The third critical component in any potentially unethical behavior is opportunity. Opportunity can be defined as the ‘presence of a favorable combination of circumstances that makes a particular course of action possible’ (McKendall and Wagner 1997, p. 626).

One source of opportunity for executives is ambiguity in the governing accounting rules. For example, there is considerable room for discretion in the ‘generally accepted accounting principles (‘GAAP’), promulgated by the Accounting Practices Board of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, as to what constitutes revenue and when it is recognized, and what constitutes an expense (as against a capital investment, for example) and when to recognize it. Similarly, Enron’s accounting treatment of off-balance partnerships was made possible, in part, by an ambiguity as to what needed to be shown on the Enron balance sheet and what could be omitted. Here are some other examples of ‘earnings management’ techniques that are made possible due to the ambiguities in GAAP: offering special end-of-quarter discounts to encourage ‘channel stuffing’ among distributors; issuing last-minute price alerts to cause a short-term buying spurt before the increase; setting up and then reversing excessive charges for restructuring; and making repeated sales of assets on a small scale rather than one big sale (Thompson et al. 2006, pp. 250–251).

The accounting rule called ‘mark-to-market’ offered similar opportunities in recent years to executives who wished to show high earnings. Buffett (2002) describes the opportunities offered by the ‘mark-to-market’ rule and its variants:

Those who trade derivatives are usually paid (in whole or part) on “earnings” calculated by mark-to-market accounting. But often there is no real market (think about our contract involving twins) and “mark-to-model” is utilized. This substitution can bring on large-scale mischief. As a general rule, contracts involving multiple reference items and distant settlement dates increase the opportunities for counterparties to use fanciful assumptions. In the twins scenario, for example, the two parties to the contract might well use differing models allowing both to show substantial profits for many years. In extreme cases, mark-to-model degenerates into what I would call mark-to-myth (p. 13).

When the motive to earn a large bonus by exaggerating earnings is combined with the means and opportunity to do so, it can be expected that unethical behavior may take place, as illustrated in this example from Buffett (2002, pp. 13–14):

But the parties to derivatives also have enormous incentives to cheat in accounting for them … I can assure you that the marking errors in the derivatives business have not been symmetrical. Almost invariably, they have favored either the trader who was eyeing a multi-million dollar bonus or the CEO who wanted to report impressive “earnings” (or both). The bonuses were paid, and the CEO profited from his options. Only much later did shareholders learn that the reported earnings were a sham.

Steps Toward Reducing Unethical Behavior

Insofar as it is the conjunction of motives, opportunities, and means that led to unethical behavior in companies such as Enron, the first step in improving corporate ethics therefore is to identify the specific policies in a company that may give rise to such a conjunction. The second step is to discover ways to loosen the combination of its components. Since all three components are usually necessary for unethical behavior to occur, it may (fortunately) be sufficient to remove just one or two of them to minimize or prevent unethical behavior.

Limiting the Motive

The granting of stock options was given as an example above regarding the role of incentives in leading to unethical behavior. If a short vesting period for stock options creates an undesirable incentive for top executives to manipulate figures so as to increase the stock price in the short run, a lengthening of the vesting period would reduce this incentive. If stock options could not be cashed in for a period of, say, 5 years after the person has left the company, then the temptation to manipulate figures to inflate stock price in the short run would be greatly reduced. This proposition is now being put into application by some companies. For example, Goldman Sachs announced that its 30-member management committee would have their bonuses paid in company stock which cannot be sold for at least 5 years, and the bonuses can be reclaimed if an executive is later accused of engaging in undue risky behavior (Earth Times 2009). The US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (Clarke 2011) has proposed a regulation that would require financial institutions to defer bonuses for at least 3 years. Similarly, the European Union set guidelines in December 2010 that top managers of banks be limited to receiving no more than 20% of their bonuses in cash (Clarke 2011).

A second move in the same context is to change accounting rules to require that the granting of stock options be treated as an expense. Many large companies have for many years resisted demands to treat stock options as expenses. The publicity flowing from scandals such as Nortel, and the arguments made by eminent business people such as Warren Buffet, however, have gradually weakened this resistance, and many companies have now begun to treat stock options as expenses as soon as they are granted. Samuelson (2002) estimates that the cost of Enron’s options was about $2.4 billion between 1998 and 2000. If included as an expense in its financial statements, Enron’s profitability would have mostly disappeared, making the shares much less attractive to buyers.

Reducing the Means

As noted above, the CEOs and top management generally have a great deal of power that gives them the means to take advantage of the incentives. How can this untrammeled power be reduced? Here are a few possibilities that have emerged in the last few years.

Empowering Directors

Ms. Sherron Watkins, the whistleblower at Enron, suggests that even if a conscientious director wishes to exert vigilant oversight over the company, he or she is usually powerless to do so, since they lack access to detailed financial figures and the ability and time to analyze and interpret such figures. The directors are thus dependent on the CEO to provide them with the information they need. To counter this situation, Ms. Watkins has proposed the creation of specialized consulting firms aimed at helping company directors. Directors could thus obtain assistance from external experts such as Ms. Watkins who would examine various company accounting, financial or other data and offer their independent conclusions to the directors (Bhupta 2003).

It should be noted that such a service already exists in the US Federal government, where the Congressional Budget Office offers assistance to members of Congress so that they can question and challenge information provided by the members of the Executive branch. The independent auditor-general performs a similar function in Canada.

Using Legal Pressure to Voluntarily Reveal Ethical Problems

Although Mr. Eliot Spitzer, the former New York Attorney General, was able to take investment banks, mutual funds, and insurance companies to court for breaches of law, he has acknowledged that such actions can have only a limited effect. “The cases against Wall Street are like stopping someone for speeding on a highway. The other cars slow down for a while and then, after a certain number of miles they speed up again” (Morton 2004, p. FP5).

How can the effects of legal actions by authorities such as Mr. Spitzer (2005) be extended in their scope and duration? Mr. Stephen M. Cutler, the Chief Enforcement Officer for the US Securities and Exchange Commission, has found one way—combining a carrot and stick approach. He has asked Wall Street firms to take the initiative in confessing to ‘conflicts of interest that plague their business.’ What if they do not come forward on their own, and the SEC staff discover the problems instead? Mr. Cutler has announced to the potential violators: ‘I assure you that the consequences will be worse’ (Davis 2004, p. C1). As a consequence, numerous firms including Goldman Sachs Group and Morgan Stanley have taken the initiative to hand over to regulators lists of dozens of potential conflicts of interest.

The New York Stock Exchange, the National Association of Securities Dealers and the UK Financial Services Authority have followed in Mr. Cutler’s footsteps and have written their members asking them to disclose similar conflicts (Davis 2004, p. C1). The Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 now requires that CEOs personally certify the accuracy of their company’s financial statements, and this requirement is likely to further strengthen the ability of law enforcement officials to challenge illegal behavior in courts.

As with accountants, lawyers are also frequently involved in advising CEOs on whether a prospective decision would be legal. To deal with this involvement, the SEC staff proposed a rule requiring that a lawyer undertake a ‘noisy withdrawal’ from representing the client if the lawyer believed that malfeasance had occurred in a decision and that the company had not adequately responded to the evidence. This proposal did not receive final SEC approval for implementation (Paton 2007, p. A17).

The convictions in the Hollinger case have, however, created a new and higher set of expectations for lawyers advising clients. Mark Kipnis and Peter Atkinson, corporate legal counsel for Hollinger, were charged with criminal offenses for their role in giving legal advice on the scheme to divert money from ordinary shareholders to the controlling shareholders, primarily Conrad Black. The jury in the Federal court trial in Chicago convicted them and the judge imposed a 6-month home detention on Kipnis and a 2-year prison term on Atkinson (Marek 2007). This decision will increase pressure on lawyers not only to advise clients against engaging in illegal acts, but also to not remain silent when they become aware of such activity. “The jury’s message is the latest in a series of challenges since Enron to the traditional way in which lawyers view their responsibilities as zealous advocates for their clients” (Paton 2007, p. A17).

Improving Whistleblower Protection

A number of attempts have been made in the US and other jurisdictions to provide protection to those who blow the whistle on unethical or illegal conduct. These attempts have been largely ineffective in protecting whistleblowers (Dworkin 2007). Dworkin argues that the experience with the False Claims Act shows that an effective way of encouraging and protecting whistleblowers is by offering them rewards for providing valuable information. Unless whistleblower protection is made more effective, most subordinates will remain reluctant to speak up when they see instances of abuse by their superiors, especially the CEO. For example, Watkins, the whistleblower at Enron, comments: “Whistleblowing is something I wouldn’t advise for anyone. I’ve kept up with my two new friends who were with me on the cover of Time. They’re going through a tough time because they’re trying to make a living within their organizations. Consider your own family, get yourself a job and then on your last day speak out” (Bhupta 2003).

Reducing Opportunities

The ambiguity in many GAAP provides executives with the opportunity to misuse the incentive. As mentioned above, one of the major problems with companies like Enron was that they used the so-called off-balance sheet financing to disguise their real level of debt compared to their assets. A survey by Forbes Magazine (Trainer 2010) showed that 2,900 companies had off-balance sheet debt, amounting to over $765 billion in corporate liabilities that had been invisible, thus making the companies look much better managed than was the case. In response to this problem, the Financial Accounting Standards Board in the US, along with the International Accounting Standards Board, has proposed new regulations to guide how obligations such as ‘operating leases’ should be disclosed in financial statements (FASB 2011). It should be noted that accounting bodies such as the Accounting Practices Board of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants have made numerous attempts to tighten the rules to reduce the ambiguities, but each time they do so, new ambiguities tend to appear. Thus, whether the new regulations proposed by FASB will succeed remains to be seen.

Perhaps a more effective factor in reducing opportunities for unethical behavior is the emergence of the Internet. Tapscott and Ticoll (2003) argue that corporations are going to be increasingly ‘naked’ in the age of the Internet, and will operate in something of a transparent fishbowl. Similarly, Seidman (2004, p. 135) notes that the “profound impact of technology has enabled greater transparency in evaluating business, institutions, and organizations. The corporate veil has been pierced.” Thus, Henry Blodget’s e-mails were leaked by various individuals, and this in turn led to the evidence the New York State Attorney General needed to file a charge against Merrill Lynch and other parties involved in the shady transactions. The increased likelihood of being found out, due to the fishbowl transparency created by the Internet, is likely to discourage use of opportunities created by ambiguous accounting rules. Table 2 outlines the recommended steps companies can take to reduce unethical behavior.

The Interaction of MMO as a Dynamic Process

The above discussion raises a further question regarding implementation. If it is possible to reduce the ethical hazard by removing one or more of its components, which component should we aim to remove first? Unfortunately there is a lack of empirical studies at present which could help us answer this question. This is because as pointed out by McKendall and Wagner (1997, p. 625) “most conceptual models of corporate illegality are complex and interactive … [and] most empirical research has tested only for simple, zero-order effects,” a comment which echoes a similar finding in the Kish-Gephart et al. (2010, p. 7) meta-analysis. In the legal field, of course, courts have been interested in establishing whether an alleged criminal had the MMO to commit the crime rather than judging the strength of each of these elements. However, it is possible to answer the question on conceptual grounds to some extent, supported by certain evidence.

Although a conjunction of MMOs is generally necessary for illegal or unethical behavior to take place, there are some exceptions. For example, sometimes a criminal commits a crime which seems to be senseless and random. A more important consideration, however, is that a conjunction of the three components leading to an ethical hazard is not a static process, but a dynamic one. This is because a person who has the motive but lacks the means or opportunity may not wait passively until the means or opportunity become available. Instead such a person may systematically go about creating the missing element, whether it be the means or the opportunity.

Labaton (2008) gives an interesting example of this which is particularly relevant to the financial crisis of 2008. He describes how the executives of major US investment banks such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley had the motive to expand their lending activities, and also the opportunity to do so. There was a lack of means, however, because what they wanted to do was not permitted at that time under the regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission. In his article, Labaton (2008) describes how the investment bank executives used their control over their firms’ lobbying resources as the means to influence government officials to create the opportunity for their companies to greatly increase their profits. The added profits then generated very large bonuses for the executives.

Labaton (2008, p. A2), a New York Times reporter, describes a seemingly unimportant meeting that took place on April 28, 2004, that he thinks may have eventually led to problems at major financial firms spiraling out of control. On this day, “the five members of the Securities and Exchange Commission met in a basement hearing room to consider an urgent plea by the big investment banks.” The plea came primarily from the five big investment banks—they wanted the SEC to relax a rule that limited how much debt they could undertake to support their business activities. Labaton (2008, p. A23) notes that the meeting was sparsely attended—none of the major media outlets, including the New York Times, covered it. After 55 min of discussion, the chairman called for a vote. All five SEC commissioners voted in favor of approving the request of the investment banks.

As a result of the rule change, leverage used by the investment banks increased significantly over the next few years. At Bear Stearns, for example, it rose to a debt to equity ratio of 33. The profits of the investment banks also increased significantly in the following few years. The CEOs of the investment banks, in turn, earned very large bonuses.

It is a matter of some irony that the case for the five investment banks was led by Goldman Sachs. Its chief executive at the time was Henry Paulson. Mr. Paulson later went on to become the Secretary of the Treasury, and, in that role, led the attempt in September 2008 to deal with the financial crisis with measures such as a $700 billion rescue package for ‘too-big-to-fail’ financial institutions embroiled in the crisis, including Goldman Sachs.

A second example of someone with a motive creating an opportunity is given by Lehrer (2011). This example describes members of organized crime syndicates looking for ways to make more money, this time by finding weaknesses in the multi-million lotteries operated by many states and Canadian provinces. There are several indications that various state lotteries have been tampered with in some way, either by finding a pattern in the way the scratch tickets are printed, by bribing certain individuals involved in producing or distributing the tickets, or by buying winning tickets to convert illicitly gained money into legitimate money. A Massachusetts state auditor report, for example, describes a long list of troubling findings, such as the fact that one person cashed in 1,588 winning tickets between 2002 and 2004 for a grand total of $2.84 million (Lehrer 2011).

These examples of individuals who successfully created opportunities and means to achieve their goal of obtaining money by unethical means suggest the following conclusion: in order to reduce the likelihood of managers engaging in unethical behavior one should, if possible, first focus on reducing the motive by changing the reward structure. This is consistent with Kerr’s argument (1975, 1995) that it is a ‘folly to reward A while hoping for B.’

This conclusion is further supported by the fact that it is clearly within the authority of a company to modify its reward structure if it might be creating an incentive for staff to engage in unethical behavior. By contrast, means and opportunity are often elements of a company’s environment as seen in the investment bank example above (Labaton 2008). Thus, it is much more difficult to attempt to change policies of outside agencies than it is to change internal policies (although even the latter is not always easy to bring about due to resistance to such a change from various interested parties).

After the reward structure has been modified to remove the undesirable incentives, the company should consider the feasibility of modifying means and opportunities. Which of these is easier to modify is likely to vary from company to company and would have to be decided on a case by case basis. This in turn would be part of the task assigned to the ‘ethical hazard marshal,’ whose role is outlined in the next section.

Creating the Role of an ‘Ethical Hazard Marshal’

Many of the actions outlined above to reduce motive, opportunities, and means relied on law enforcement agencies, and were undertaken after the problem had already become apparent. Though valuable, such remedial actions need to be supplemented by a specialized mechanism designed to prevent unethical behavior from taking place.

Nader’s book Unsafe at Any Speed (1965) had an interesting but less well-known subtitle: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile. Similarly, this article has argued that unethical behavior is also frequently ‘designed-in’ by company policies that create ethical hazards by providing a motive, opportunities, and means to act unethically. Companies need to proactively anticipate the risk of unethical behavior, therefore, by examining their major policies and regulations to see whether some of them may be unwittingly creating ethical hazards.

The analogy of a fire marshal is instructive here. A fire marshal has the responsibility (and the necessary expertise) to examine buildings to look for potential fire hazards when a building is being built, and also periodically after it has been built. The fire marshal’s role is to prevent fires rather than to put them out after they have started. Using a similar logic, there is a need for the position of an ‘ethics marshal’ or an ‘ethical hazards officer.’ This officer would have the responsibility, authority and expertise to examine current and proposed company policies to identify ethical hazards.

The role of an ethical hazard marshal proposed here is quite different from that of an ‘ethics officer.’ An increasing number of companies have created a position of an ethics officer as noted by Hill and Jones (2007, p. 404), Ferrell et al. (2005, p. 39), and Langton and Robbins (2007, p. 453). The role of these ethics officers is akin to that of a police officer, namely to ensure that current rules and regulations are adhered to. Moreover, they tend to deal with ethical breaches at a relatively low level in the company hierarchy as illustrated by the following quotations:

These individuals are responsible for making sure that … the company’s code of ethics is adhered to … In many businesses, ethics officers act as internal ombudsperson with responsibility for handling confidential inquiries from employees, investigating complaints from employees or others, reporting findings …” (Hill and Jones 2007, p. 404); and

[M]ore than 120 ethics specialists now offer services as in-house moral arbitrators, mediators, watchdogs, and listening posts … These corporate ethics officers hear about issues such as colleagues making phone calls on company time, managers yelling at their employees, …” (Langton and Robbins 2007, p. 453).

The ethical hazard marshal’s role as described here, by contrast, is at the preventive and policy level—to identify potential ethical problems that can be anticipated or predicted to take place within the framework of a current or proposed policy, and to bring these to the attention of senior managers or the board of directors.

Independence of the Ethical Hazards Marshal

The creation of the position of an ‘ethical hazard marshal’ raises a number of interesting issues such as who would appoint the officer and to whom the officer would report.

The position of the ethical hazard marshal would require a great deal of autonomy to be able to deal with sensitive issues such as the wisdom of giving stock options to the CEO. Considerable pressure is thus likely to be brought upon such an officer. The ‘ethics marshal’ therefore would ideally be employed by an independent regulatory body, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, just as a fire marshal is employed not by building owners but by the local municipality. Until such time as legislation making such an independent appointment is established, however, it may be necessary for companies to appoint their own marshals, and to attempt to give them adequate protection. Since the position would obviously have a significant cost attached to it, perhaps only companies above a certain size might be expected (or required) to create such a position.

Where the marshal is employed by a company, the appointee should ideally be chosen directly by the board of directors, and perhaps should also report to it. Many ombudspersons hold similarly sensitive posts, and it is possible that the appointment and reporting process for ethical hazard officers could be modeled after that of an ombudsperson.

The key role of the ethical hazards marshal is to examine current or proposed policies (on stock options, for example), to identify whether they may give rise to unethical behaviors, and if so to report the conclusion to top management and/or the board of directors. The marshal may also be given the autonomy to decide if in some very important matters the report should be sent to shareholders at large as well.

The company management, or the board, may still implement the policy if they believe that the anticipated ethical hazard is not as significant as the ethical hazards marshal believes. However, the fact that the hazard has been identified and publicized would reduce the likelihood that such a policy would be continued or adopted. Furthermore, if a law enforcement agency should subsequently take the company to court for an illegal act, the managers and the board would not be able to claim that they were not aware of the possibility of such illegal acts taking place.

Conclusion

Unethical and in some cases criminal actions in recent years by executives in many large companies have highlighted the need to prevent such reprehensible behavior in the future. It is possible that some of the ethical lapses were caused, to paraphrase Schminke (2009), because some of the executives were ‘simply unaware of the specific ethical standards they are expected to uphold.’ As suggested in Table 1, modifying selection criteria, creating, and enforcing a code of ethics and offering training in business ethics would be helpful steps for such executives. Others, however, may be among those who ‘are aware of these standards but choose not to uphold them’ (Schminke 2009, p. 587). This article has suggested that actions by this latter group of executives can be analyzed in terms of their motives, and the opportunities and means available to them. The conjunction of motive, opportunities and means creates an ethical hazard which increases the probability of unethical behaviors. By creating a process to identify and remove such ethical hazards, one could reduce the probability of unethical behavior, somewhat in the same way that one can reduce the probability of a fire by removing fire hazards in a building.

As seen in the modified terms for bonuses to be offered to the 30-member management committee at Goldman Sachs (Earth Times 2009), some corporations are now taking steps along the lines suggested here. The passage of laws such as the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, and the conviction and jailing of many executives who engaged in criminal activities, are also likely to reduce the likelihood of future corporate misbehavior. This article has recommended a number of other steps that could be taken to reduce corporate misbehavior, especially the creation of a position of an ‘ethical hazards marshal’ similar in spirit to the position of a fire marshal, who would identify and publicize potential ethical hazards and work at systematically reducing them.

References

AACSB. (2007). The latest in business ethics education. (http://www.aacsb.edu/resource_centers/ethicsedu/thelatestinbusinessethicseducation.pdf. Accessed 15 Sep 2008.

Ackman, D. (2002, March 22). Did Enron execs ‘dump’ shares? Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/2002/03/22/0322enronpayside.html. Accessed 20 Feb 2010.

Acton, J. E. (1887). Absolute power corrupts absolutely. Letter to Bishop Mandell Creighton. http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/absolute-power-corrupts-absolutely.html. Accessed 20 Feb 2010.

Ainslie, G. (1992). Picoeconomics: The strategic interaction of successive motivational states within the person. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Asch, S. (1958). Effects of group pressure on the modification and distortion. In E. E. Maccoby, T. M. Newcomb, & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Ashforth, B. E., & Anand, V. (2003). The normalization of corruption in organizations. In R. M. Kramer & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 25, pp. 1–52). Oxford: Elsevier.

Ashkanasy, N. M., Windsor, C. A., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Bad apples in bad barrels revisited: Cognitive moral development, just world beliefs, rewards and ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics Quarterly, 16(1), 449–473.

Aspen Institute Center for Business Education. (2010). The global 100. Survey published in Beyond grey pinstripes. http://www.beyondgreypinstripes.org/rankings/index.cfm.

Barrett, T., Walsh, D., & Keilar, B. (2008). AIG bailout upsets Republican lawmakers. Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://www.cnn.com/2008/POLITICS/09/17/aig.bailout.congress.

Baucus, M. S., & Beck-Dudley, C. L. (2005). Designing ethical organizations: Avoiding the long-term negative effects of rewards and punishments. Journal of Business Ethics, 56, 355–370.

Baucus, M. S., Norton, W. I., Jr., Baucus, D. A., & Human, S. E. (2008). Fostering creativity and innovation without encouraging unethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 81, 97–115.

BBC News. (2008). Bear Stearns ex-managers charged. Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7463713.stm.

Beggs, J. M., & Lund Dean, K. (2007). Legislated ethics or ethics education? Faculty views in the post-Enron era. Journal of Business Ethics, 71, 15–37.

Bhupta, M. (2003, August 29). The woman who brought down Enron. Times News Network.

Buffett, W. (2002). Chairman’s letter to the shareholders. Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report. http://www.berkshirehathaway.com/2002ar/2002ar.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2010.

Cadsby, C. B., Song, F., & Tapon, F. (2007). Sorting and incentive effects of pay for performance: An experimental investigation. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 387–405.

Christensen, J. L., Peirce, E., Hartman, L., Hoffman, W. M., & Carrier, J. (2007). Ethics, CSR, and sustainability education in the financial times top 50 global business schools: Baseline data and future research directions. Journal of Business Ethics, 73, 347–368.

Clarke, D. (2011). U.S. regulator proposes deferring some bank executive bonuses. Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/41461231/ns/business-stocks_and_economy/.

Coffee, J. C. Jr. (2005). A theory of corporate scandals: Why the U.S. and Europe differ. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(2), 198. Also available as Columbia University Working Paper, ssrn.com/abstract=694581. Accessed 10 Mar 2007.

Commonwealth vs. Michael M. O’Laughlin. (2005). Burglary, armed assault in a dwelling, assault and battery by means of a dangerous weapon, practice, criminal, required finding. Appellate Court Decision, No. 04-P-48.

Dalton, D. R., Hitt, M. A., Certo, S. T., & Dalton, C. M. (2007). The fundamental agency problem and its mitigation: Independence, equity, and the market for corporate control. Academy of Management Annals, 1, 1–64.

Davis, A. (2004, November 4). Wall Street’s ‘conflict reviews’: What’s the next step? The Wall Street Journal, p. C1.

Davis, G. F. (2009). The rise and fall of finance and the end of the society of organizations. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 23, 27–44.

Devinney, T. M. (2009). Is the socially responsible corporation a myth? The good, the bad, and the ugly of corporate social responsibility. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 23, 44–56.

Dworkin, T. M. (2007). Sox and whistleblowing. Michigan Law Review, 105(8), 1757–1780.

Earth Times. (2009). In nod to public anger, Goldman Sachs bonuses to be paid in stock. http://www.earthtimes.org/articles/show/298777,in-nod-to-public-anger-goldman-sachs-bonuses-to-be.html. Accessed 10 Jan 2010.

Epley, N., & Dunning, D. (2000). Feeling ‘holier than thou: Are self-serving assessments produced by errors in self-or social predictions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 6.

Evans, M. (2007). Former Nortel CEO John Roth not connected to lawsuit-so far. Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://seekingalpha.com/article/29468-former-nortel-ceo-john-roth-not-connected-to-lawsuit-so-far.

FASB (Financial Accounting Standards Board). (2011). Leases—joint project of the FASB and the IASB: Update. Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://www.fasb.org/cs/ContentServer?c=FASBContent_C&pagename=FASB%2FFASBContent_C%2FProjectUpdatePage&cid=900000011123.

Ferrell, O. C., Hirt, G., Bates, R., & Currie, E. (2005). Business: A changing world (2nd ed.). Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4(1), 75–91.

Gioia, D. A. (2002). Business education’s role in the crisis of corporate confidence. Academy of Management Executive, 16(3), 142–144.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Wheeler, A. R., & Buckley, M. R. (2005). Everybody else is doing it, so why can’t we? Pluralistic ignorance and business ethics education. Journal of Business Ethics, 56(4), 385–398.

Hegarty, W. J., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (1979). Organizational philosophy, policies and objectives related to unethical decision behavior: A laboratory experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64, 331–338.

Hill, C. W. L., & Jones, G. R. (2007). Strategic management and theory: An integrated approach (7th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Janice, I. L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Kerr, S. (1975, 1995). On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B. Academy of Management Journal, 18, 769–782. (Reprinted as a classic in Academy of Management Executive: 1995, 9(1), 7–14.)

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Trevino, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 1–31.

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Kotowitz, K. (1987). Moral philosophy. In J. Eatwell, M. Milgate, & P. Newman (Eds.), The New Palgrave—a dictionary of economics (Vol. 3). London: Macmillan Press.

Labaton, S. (2008, October 3). Agency’s ’04 rule let banks pile up new debt, and risk. Plans to increase S.E.C. scrutiny of firms faltered. The New York Times, pp. A2 and A23.

Langton, N., & Robbins, S. (2007). Organizational behaviour (3rd ed.). Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Lehrer, J. (2011, February). Cracking the scratch lottery code. Wired. http://www.wired.com/magazine/2011/01/ff_lottery/all/1. Accessed 12 Aug 2011.

Lerner, G. (2006). How teaching political and ethical theory could help solve two of the legal profession’s biggest problems. The Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics, 19(3), 781. 794.

Marek, L. (2007). Ex-Hollinger general counsel Kipnis escapes jail. Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://www.legalweek.com/Navigation/34/Articles/1079249/Ex-Hollinger+general+counsel+Kipnis+escapes+jail.html.

McCafferty, J. (2009, June 12). Splitting the CEO and the chair. Bloomberg Business Week. http://www.businessweek.com/managing/content/jun2009/ca20090612_359612.htm. Accessed 15 Aug 2011.

McClelland, D. C. (1985). How motives, skills and values determine what people do. American Psychologist, 40, 812–825.

McKendall, M. A., & Wagner, J. (1997). Motive, opportunity, choice, and corporate illegality. Organization Science, 8, 624–647.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority. New York: Harper and Row.

Moberg, D., & Romar, E. (2003). WorldCom. http://www.scu.edu/ethics/dialogue/candc/cases/worldcom.html. Accessed Sep 2008.

Moorhead, G., & Griffin, R. W. (1998). Organizational behavior, managing people and organizations (5th ed.). New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Moreira, H., & Petersmeyer, W. (2009, December 1). The MBA oath: Toward a more perfect world. Business Week. http://www.businessweek.com/bschools/content/nov2009/bs20091130_499190.htm. Accessed 10 Feb 2010.

Morton, P. (2004, December 4). The Wyatt Earp of Wall Street. National Post, p. FP5.

Nader, R. (1965). Unsafe at any speed: The designed-in dangers of the American automobile. New York: Grossman.

Needleman, M. L., & Needleman, C. (1979). Organizational crime: Two models of criminogenesis. Sociological Quarterly, 20, 517–528.

Pajunen, K. (2006). Living in agreement with a contract: The management of moral and viable firm–stakeholder relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(3), 243–258.

Palmer, D., & Maher, M. W. (2006). Developing the process model of collective corruption. Journal of Management Inquiry, 15, 363–370.

Paton, P. D. (2007, July 19). Suddenly, they’re holding corporate counsel to a higher standard. The Globe and Mail, p. A17.

Pinto, J., Leana, C. R., & Pil, F. K. (2008). Corrupt organizations or organizations of corrupt individuals? Two types of organization-level corruption. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 685–709.

Ross, M., & Fletcher, G. J. O. (1985). Attribution and social perception. In G. Lindsey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 73–114). New York: Random House.

Rotter, J. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1–28.

Samuelson, R. J. (2002, January 30). Stock option madness. Washington Post. http://www.law.harvard.edu/faculty/bebchuk/pdfs/Samuelson_WashPost.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2009.

Schminke, M. (2009). Editor’s comments: The better angels of our nature—ethics and integrity in the publishing process. Academy of Management Review, 34(4), 586–591.

Seidman, D. (2004). The case for ethical leadership. Academy of Management Executive, 18(2), 134–138.

Skinner, B. F. (1969). Contingencies of reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Oxford: Oxford University Press Edition; 1998.

Spitzer, E. (2005). Statement to the National Press Club. Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4472927.

St. Eve, A. (2007). Judgment in the Hollinger case (p. 30). http://www.ilnd.uscourts.gov/judge/st_eve/black/doc929.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan 2009.

Steel, P., & Konig, C. J. (2006). Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 889–913.

Tapscott, D., & Ticoll, D. (2003). The naked corporation—how the age of transparency will revolutionize business. Toronto: Viking Canada.

Thompson, A. A., Jr., Gamble, J. E., & Strickland, A. J., I. I. I. (2006). Strategy: Winning in the marketplace (2nd ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Trainer, D. (2010). Off-balance sheet debt: Bad enough that FASB notices, maybe you should too? Accessed 15 Aug 2011, from http://blogs.forbes.com/greatspeculations/2010/11/08/off-balance-sheet-debt-bad-enough-that-fasb-notices-maybe-you-should-too/.

Trevino, L. K. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person–situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 601–617.

Trevino, L. K., & Brown, M. E. (2004). Managing to be ethical: Debunking five business ethics myths. Academy of Management Executive, 18(2), 69–81.

Trevino, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990.

Trevino, L. K., & Youngblood, S. A. (1990). Bad apples in bad barrels: A causal analysis of ethical decision-making behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(4), 378–385.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

U. S. District Attorney. (2007). Government’s evidentiary proffer in Case No. 05 CR 727, US District Court, Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division. http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/iln/indict/2006/us_v_black_et_al_santiago_proffer.pdf. Accessed 11 Jan 2009.

Van Eerde, J. B., & Thierry, H. (1996). Vroom’s expectancy models and work-related criteria: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 575–586.

Verschoor, C. C. (2006). IFAC committee proposes guidance for achieving ethical behavior. Strategic Finance, 88(6), 19.

Vroom, V. (1964). Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). The Lucifer effect. New York: Random House.

Zimbardo, P. G., Banks, W. C., Haney, C., & Jaffe, D. (1973, April 8). A Pirandellian prison. The New York Times Magazine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pendse, S.G. Ethical Hazards: A Motive, Means, and Opportunity Approach to Curbing Corporate Unethical Behavior. J Bus Ethics 107, 265–279 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1037-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1037-0