Abstract

Limited data are available regarding patterns of chemotherapy receipt and treatment-related toxicities for older women receiving adjuvant trastuzumab-based therapy. We used surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER)-Medicare data to identify patients ≥66 years with stage I–III breast cancer treated during 2005–2009, who received trastuzumab-based therapy. We examined patterns of chemotherapy receipt, and using multivariable logistic regression, we examined associations of age and comorbidity with non-standard chemotherapy. In propensity-weighted cohorts of women receiving standard and non-standard trastuzumab-based therapy, we also examined rates of (1) hospital events during the first 6 months of chemotherapy and (2) short-term survival. Among 2,106 women, 29.7 % were aged ≥76 and 66 % had a comorbidity score = 0. Overall, 31.3 % of women received non-standard chemotherapy. Compared to patients aged 66–70, older patients more often received non-standard chemotherapy [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 4.1, 95 % confidence interval (CI) = 3.40–4.92 (ages 76–80); OR = 15.3, 95 %CI = 9.92–23.67 (age ≥ 80)]. However, comorbidity was not associated with receipt of non-standard chemotherapy. After propensity score adjustment, hospitalizations were more frequent in the standard (vs. non-standard) group (adjusted OR = 1.7, 95 % CI = 1.29–2.24). With a median follow-up of 2.8 years, 276 deaths occurred; the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for death was lower in standard versus non-standard treated women (HR = 0.69, 95 % CI = 0.52–0.91). Among a population-based cohort of older women receiving trastuzumab, nearly one-third received non-standard chemotherapy, with the highest rates among the oldest women. Non-standard chemotherapy was associated with fewer toxicity-related hospitalizations but worse survival. Further exploration of treatment toxicities and outcomes for older women with HER2-positive breast cancer is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is overexpressed in approximately 20–25 % of breast cancers [1, 2], although rates of HER2-positive disease may be lower in older populations [3, 4]. Trastuzumab given concurrently or sequentially with chemotherapy improves survival for women with HER2-positive non-metastatic tumors [5–7], and multiple adjuvant regimens are approved for use [8].

Despite the significant efficacy of trastuzumab, evidence suggests that older women are less likely to initiate trastuzumab-based adjuvant regimens than younger women [9], and among those who initiate trastuzumab, older women and those with more comorbid illness are less likely to complete a full year of therapy [10]. Other evidence suggests that women aged ≥70 are less likely than younger women to receive guideline-recommended chemotherapy regimens for breast cancer [11]. Although the reasons for less guideline-recommended care in older patients are likely multifactorial, this may occur, at least in part, because of the limited evidence on the efficacy and toxicity of anti-cancer therapies among older adults. In fact, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) breast cancer guidelines state that there are “insufficient data” to make definitive chemotherapy recommendations for women >70 years of age [8].

Although under-utilization of therapy in older patients with breast cancer has been demonstrated, few data are available about the chemotherapy regimens administered to older women with HER2-positive disease, including use of chemotherapy regimens that have not been examined or proven effective in the adjuvant setting (i.e., non-standard chemotherapy). In this study, we examined patterns of trastuzumab-based chemotherapy regimens, factors associated with receipt of non-standard chemotherapy, chemotherapy-related toxicity, and short-term survival for older women receiving adjuvant trastuzumab using data from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare.

Patients and methods

Data

The SEER program of the National Cancer Institute reports information from population-based registries in areas representing 28 % of the US population [12]. SEER registrars uniformly report information from medical records on patient demographics, tumor characteristics, treatments, and mortality for all incident cancers. Since 1991, SEER data have been linked with Medicare administrative data for individuals enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare [13], successfully matching >93 % of persons aged ≥65 in SEER [13, 14]. For this study, we used the medicare provider analysis and review, hospital outpatient standard analytic, durable medical equipment, and the carrier claims files. Since this study used previously collected, de-identified data, it was deemed exempt for review by the Offices for Human Research Studies at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Study cohort

We identified women aged ≥66 with a first invasive breast cancer diagnosed in June 2005 or later (coinciding with timing of the initial national presentations of the large adjuvant trastuzumab trials [5, 6] ). We included women with histologies likely to be treated by routine guidelines and who were enrolled in Parts A/B fee-for-service medicare and not a health maintenance organization (HMO) during the 12 months before diagnosis (because claims for HMO patients are not available) (n = 68,965). We excluded women diagnosed at autopsy (n = 678), those without claims during −45 days through +180 days after diagnosis (n = 283), and those with stage 0, IV, or unknown stage (n = 18,314). We restricted the cohort to women who underwent mastectomy or breast conserving surgery, who had at least one J code for trastuzumab (J9355) within 365 days of diagnosis and who were enrolled in Parts A/B fee-for-service Medicare and not an HMO within 18 months after diagnosis (n = 2,288). Finally, we excluded patients who received trastuzumab-based therapy later in their treatment course (i.e., not as part of an initial chemotherapy regimen) (n = 2) and those initiating trastuzumab in 2010 because of the limited follow-up (n = 135). In total, we included 2,106 patients who initiated trastuzumab during June 2005–December 2009.

Receipt of non-standard chemotherapy

We reviewed treatment claims (J-codes) during the first 365 days after diagnosis for each woman and assigned treatment regimens based on the first chemotherapy regimen administered (Table 4 in Appendix). We defined standard adjuvant therapy as any adjuvant chemotherapy regimen recommended by the NCCN [8, 11] and administered concurrently or sequentially with trastuzumab (Table 1) [4–6]. For treatment to be sequential, trastuzumab had to directly follow chemotherapy [6]. All other regimens are considered non-standard and are categorized as per Table 1 [11].

Toxicity and survival

We identified hospitalizations and emergency room (ER) visits with a primary diagnosis code suggesting potential chemotherapy-related toxicity during the first 6 months after chemotherapy initiation [15, 16]. As per prior studies [15, 16], we assessed infections, fever, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, nausea/emesis, diarrhea, dehydration/electrolyte abnormality, malnutrition, constitutional symptoms, nonspecific treatment complications, thrombosis, thyroid disorders, fractures, asthma, pulmonary conditions, renal failure, and headaches. We also examined additional conditions that could be associated with chemotherapy/trastuzumab, such as cardiac events [10], mucositis/stomatitis, diabetes, and liver dysfunction (Table 5 in Appendix). We examined overall survival and breast cancer-specific survival based on the National Death Index data.

Independent variables

Independent variables of interest included age at diagnosis and Charlson comorbidity score [17, 18]. Control variables included race/ethnicity, year of treatment initiation, median household income and percent with high school diplomas (based on Census tract of residence from US Census data; the 1 % of patients with missing zip codes were assigned median values and categorized in quartile 2), marital status, SEER region (combining some registries given small sample sizes), location of residence, tumor size, number of positive nodes, stage, and hormone receptor [HR] status (positive if estrogen receptor [ER] or progesterone receptor [PR] positive, negative if ER and PR negative; the 8 % of patients with unknown HR status were considered HR-positive, consistent with receptor status for most breast cancer patients) [14]. Variables are categorized as in Table 2.

Statistical analysis

We first described standard and non-standard chemotherapy regimens given concurrently or sequentially with trastuzumab, and performed χ 2 tests to examine differences in patient characteristics between groups. We used logistic regression to assess the odds of receipt of non-standard chemotherapy by age and comorbidity, adjusting for the control variables listed above. We used generalized estimating equations to account for clustering within registries. In a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the model after excluding 35 patients diagnosed with subsequent cancers (10 colorectal, 7 lung, 18 other) during the first 6 months of chemotherapy; results were similar and are not presented.

Since patients who received non-standard chemotherapy differed from patients who received standard chemotherapy, we compared hospital events and survival for women who received standard and non-standard chemotherapy using a propensity score analysis [19, 20]. To calculate propensity scores, we fit the logistic regression model with all of the covariates described above and obtained the predicted probability (p) of receiving non-standard treatment based on each individual’s characteristics. For each patient, a weight was assigned as the inverse probability of belonging to the group that they are in (inverse probability of treatment weight) [19]. Thus, the weight was 1/p for those receiving non-standard chemotherapy and 1/(1−p) for patients receiving standard chemotherapy. The characteristics of the weighted cohort are displayed in Table 6 in Appendix and are well balanced. We then compared the proportion of patients having a hospital event by standard and non-standard chemotherapy in the propensity-weighted cohort using logistic regression, adjusting for all independent variables to give unbiased variance estimates to the adjusted odds ratios (OR) [20–22].

For survival outcomes, the start date was the first date of chemotherapy or trastuzumab (whichever came first). Women were censored on December 31, 2010 (last date for which claims were available) or sooner if they disenrolled from Parts A/B fee-for-service medicare. We repeated the survival analyses after restricting to those starting treatment by December 31, 2008 to ensure at least 2 years of potential follow-up. We estimated survival functions for non-standard and standard treatment using weighted Kaplan–Meier methods, and compared survival (breast cancer-specific and overall) for the propensity-weighted cohort using a Cox proportional hazards model, adjusting for all independent variables.

Since the propensity score analyses can adjust only for observed characteristics, we examined the robustness of our findings to potential unobserved confounders [23]. To do this, we assumed an unobserved variable exists, such as poor performance status (PS), associated with both receipt of non-standard chemotherapy and worse survival. We then re-estimated the association of non-standard chemotherapy and survival after adjusting for this additional unmeasured variable (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS ≥ 2), assuming that poor PS was twice as prevalent in the non-standard group than the standard group (≈10 %) [24] and was associated with two times higher risk of death [25].

Results

Patient characteristics and clinical variables are shown in Table 2. Among 2,106 women, 40.4 % were aged 66–70 and 11.7 % were aged ≥80. Most women had Charlson scores of 0-1. The most common trastuzumab-based chemotherapy regimens were docetaxel-carboplatin (TCH, 29.6 %), doxorubin-cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel (ACT, 17.6 %), trastuzumab without chemotherapy (i.e., trastuzumab alone, 15.1 %), taxane only (9.8 %), and AC (4.9 %) (Table 1).

Receipt of standard versus non-standard chemotherapy

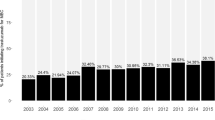

Overall, 660 women (31.3 %) received non-standard chemotherapy. Differences by patient characteristics are shown in Table 2. In unadjusted analyses, receipt of non-standard chemotherapy increased with age, with 16.8 % of women aged 66–70 receiving non-standard chemotherapy compared with 72.4 % of women aged ≥80 (p < .0001). Rates of non-standard chemotherapy were non-significantly higher for women with comorbidity score ≥2 (37.9 %) versus comorbidity score = 0 (30.6 %, p = 0.06) (Table 2).

In adjusted analyses assessing receipt of non-standard chemotherapy (Table 2), older age (vs. ages 66–70) was strongly associated with non-standard chemotherapy [OR = 1.82, 95 % Confidence interval (CI) = 1.47–2.25 for ages 71–75; OR = 4.09, 95 % CI = 3.40–4.92 for ages 76–80; OR = 15.33, 95 %CI = 9.93–23.67]. Comorbidity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic variables were not significantly associated with non-standard chemotherapy, although residing in a major metropolitan area was associated with higher odds of non-standard chemotherapy (vs. other urban/rural categories). In addition, more lymph node involvement was associated with less non-standard chemotherapy (vs. node-negative disease).

Toxicity and survival

Overall, 562 patients (26.7 %) had 906 toxicity-associated hospitalizations or ER visits (443 patients had ≥1 hospitalization, 217 patients had ≥1 ER visit) in the 6 months after chemotherapy initiation. After propensity weighting and regression adjustment for all independent variables, patients receiving standard (vs. non-standard) chemotherapy had higher odds of toxicity-associated hospitalization (22.4 vs. 18.0 %, p = 0.001; OR = 1.70, 95 %CI = 1.29–2.24) and having either an ER visit or hospitalization (28.8 vs. 21.9 %, p = 0.0002; OR = 1.72, 95 %CI = 1.32–2.24) but non-significantly higher odds of an ER visit (11.2 vs. 8.3 %, p = 0.11; OR = 1.43, 95 % CI = 0.98–2.09). The reasons for each of the 856 hospital events in the weighted cohort are shown in Table 3 by treatment. The most common primary diagnosis codes were infection, breast cancer, delirium, and neutropenia. Among these, the proportion with infection and neutropenia was lower for women in the non-standard versus standard treatment groups (p = .002 for infection and p > .0001 for neutropenia).

There were 276 deaths during a median 2.8 years of follow-up (124 in non-standard group, 152 in standard group). The median follow-up was 2.8 years in the standard group and 2.7 years in the non-standard group, indicating no detectable ascertainment biases for survival outcomes. The propensity-weighted Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed relatively high survival, with 2 and 3-year survival estimates of 93.8 and 89.9 % for the standard chemotherapy group and 85.5 and 77.8 % in the non-standard group (Fig. 1). In the propensity-weighted Cox model including all covariates, the hazard ratio (HR) for death is 0.69 (95 % CI = 0.52–0.91), favoring the standard chemotherapy group (p = 0.009). In the sensitivity analysis restricting to patients diagnosed by December 31, 2008, results were similar (data not shown). There were 33 breast cancer-specific deaths in the weighted cohort; the adjusted HR for breast cancer death = 0.31, 95 % CI = 0.14–0.66), favoring the standard chemotherapy group. Of note, for the analysis of breast cancer-specific deaths, because of the small number of events, we did not include additional variables in the propensity-weighted model other than standard or non-standard chemotherapy.

We tested the sensitivity of the survival findings to a potential unobserved confounder: worse PS in the non-standard group. If women in the non-standard group had twice the prevalence of PS ≥ 2 as the standard group (20 vs. 10 %) and the risk of death associated with PS ≥ 2 was twice that of women with PS 0–1, then the adjusted HR from an unmatched multivariate Cox model would still be statistically significant (HR = 0.75, 95 % CI = 0.57–0.99). We would expect this to no longer be significant if prevalence were higher in both groups or if the association of poor PS with worse survival was stronger.

Discussion

In this large, population-based cohort of older women receiving trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy, nearly one-third of patients received non-standard chemotherapy. Not surprisingly, older age was strongly associated with receipt of non-standard chemotherapy. The frequency of hospital events was significantly higher for women receiving standard versus non-standard chemotherapy, but standard chemotherapy was associated with improved survival.

Our results with regard to survival should be interpreted cautiously because they are retrospective and non-randomized; we cannot rule out the possibility that non-standard chemotherapy was associated with unmeasured factors that impacted outcomes. In addition, there was significant heterogeneity in the chemotherapy received with too few patients to analyze survival by regimen. Nevertheless, our findings raise concern that providers may be under-treating patients in efforts to avoid toxicity, resulting in inferior outcomes. It is notable that our cohort had a substantial risk of recurrence, with 70 % of patients having stage II-III disease. This may have increased our ability to detect survival differences by type of chemotherapy despite a relatively modest sample size.

Although pooled analyses and observational studies have suggested substantial benefits of chemotherapy for older breast cancer patients, many older patients, and particularly those ≥70 years, do not receive guideline-recommended chemotherapy [9, 11, 26–32]. The reasons for non-standard treatment selection in our cohort may include variables we could not measure, such as comorbidity severity, PS, and preferences of patients and physicians. In almost all cases, the non-standard treatments used are known to be less toxic (i.e., single-agent chemotherapy or trastuzumab monotherapy) than standard chemotherapy regimens. However, approximately 5 % received non-standard doublet chemotherapy.

We were unable to ascertain whether the selection of non-standard regimens among women in our cohort was appropriate. One could imagine that a chemotherapy regimen perceived to be less toxic yet efficacious in the metastatic setting (i.e., single-agent vinorelbine) may be extrapolated for use in the adjuvant setting for a healthy, older patient with lower-risk disease or for an older patient with high-risk cancer but poor functional status. For patients with lower-risk tumors, recent prospective data from a large, multicenter clinical trial evaluating paclitaxel-trastuzumab in approximately 400 patients of all ages with node-negative HER2-positive breast cancer indicate highly favorable outcomes and tolerability [33, 34], with a three-year disease-free survival of 98.7 % (95 % CI = 97.6–99.8 %). We believe that the results support the use of this regimen in both younger and older women [35]. On the other hand, the administration of regimens such as trastuzumab monotherapy, or trastuzumab-carboplatin-paclitaxel and other non-standard, doublet chemotherapy may be harder to rationalize without additional efficacy and toxicity information.

Strikingly, 26.7 % of women experienced a hospital event during the first 6 months of treatment. These rates are higher than those reported in a prior analysis using SEER-Medicare data for women with stage I–IV breast cancer receiving chemotherapy, although this is likely because the prior analysis included any adjuvant or metastatic chemotherapy regimen and ascertained a more limited set of chemotherapy-related events [16]. In another analysis of younger, commercially-insured patients, 16.1 % of patients, had hospital events [15]. Our observation of higher rates of hospital events in an older population is consistent with prior studies demonstrating increased chemotherapy-related toxicity for older (vs. younger) women [26, 27] and highlight the urgent need to develop effective and non-toxic treatment regimens for older patients.

To our knowledge, this large representative study is the first to examine “real world” adjuvant chemotherapy for older patients receiving trastuzumab. However, we acknowledge several limitations. First, although medicare claims can accurately provide information on hospital events [16] and chemotherapy [36, 37], coding of specific agents may be imperfect [38]. To maximize ascertainment of each chemotherapy agent, we reviewed all patient-level claims for chemotherapeutic agents over 1 year to identify all agents with claims that were part of any regimen. Second, it is possible that some chemotherapy was administered for disease recurrence or subsequent cancers, although the number of other cancers diagnosed was small and did not impact our results. Third, the reasons for treatment selection and treatment changes were not available. Fourth, propensity methods adjust for observed confounders only; however, our sensitivity analyses suggest that large differences in unmeasured confounders would need to exist to explain our findings. Fifth, we could not examine chemotherapy-related toxicities that did not result in hospital events, nor could we specifically ascertain whether a hospital event occurred as a direct result of chemotherapy or another underlying condition. Finally, follow-up times were short. However, we repeated analyses after restriction to patients with at least 2 years of follow-up and found similar results.

In summary, we identified a substantial proportion of patients who received non-standard, trastuzumab-based chemotherapy among a large cohort of older women. Approximately, one-quarter of women experienced a hospital event due to presumed treatment-associated toxicity, with higher rates among women receiving standard chemotherapy. The higher hospital event rates did not translate into worse survival. Although some evidence in the metastatic setting suggests that trastuzumab is effective with a wide variety of chemotherapy agents given with it [6, 7, 39], this has not been consistently demonstrated in the adjuvant setting. Furthermore, the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 49907 trial demonstrated that adjuvant capecitabine (a regimen used in metastatic disease) was inferior to standard chemotherapy among older patients with early-stage breast cancer, further emphasizing our inability to extrapolate treatments from the metastatic setting. Whenever possible, evidence-based, adjuvant regimens should be strongly considered in all patients until further prospective data are available to suggest otherwise.

Our findings underscore the need to conduct high quality, prospective trials dedicated to the growing number of older patients with breast cancer, with comprehensive examination of short- and long-term toxicity, functional, and outcome assessments. In particular, there is an urgent clinical need to develop more tolerable regimens for higher risk patients that still maintain efficacy, given the very high utilization of hospital resources we observed in our study, together with our observation of inferior survival in patients administered less toxic, non-standard regimens. An upcoming, multicenter study will administer a low-toxicity regimen (trastuzumab emtansine) to older patients with HER2-positive breast cancer and will include comprehensive toxicity and efficacy endpoints. Until additional prospective data are available, the development of consensus guidelines for the treatment of older women with breast cancer may facilitate a more standardized treatment approach.

References

Cho HS, Mason K, Ramyar KX et al (2003) Structure of the extracellular region of HER2 alone and in complex with the Herceptin Fab. Nature 421:756–760

Yarden Y (2001) The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. Signalling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Eur J Cancer 37(Suppl 4):S3–S8

Clarke CA, Keegan TH, Yang J et al (2012) Age-specific incidence of breast cancer subtypes: understanding the black–white crossover. J Natl Cancer Inst 104:1094–1101

Laird-Fick H, Gardiner J, Tokala H et al (2013) HER2 status in elderly women with breast cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 4:362–367

Romond EH, Perez EA, Bryant J et al (2005) Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353:1673–1684

Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B et al (2005) Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353:1659–1672

Perez EA, Romond EH, Suman VJ et al (2011) Four-year follow-up of trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: joint analysis of data from NCCTG N9831 and NSABP B-31. J Clin Oncol 29:3366–3373

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2013) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Breast Cancer V.3.2013 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2013

Freedman RA, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA et al (2013) Use of adjuvant trastuzumab in women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer by race/ethnicity and education within the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer 119:839–846

Vaz-Luis I, Keating NL, Lin NU et al (2014) Duration and toxicity of adjuvant trastuzumab in older patients with early-stage breast cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 32:927–934

Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME et al (2007) Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol 25:2522–2527

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, Edwards BK (eds) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2008, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/, based on November 2010 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2011

SEER-Medicare: how the SEER & Medicare data are linked. http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/overview/linked.html. Accessed 20 Oct 2009

Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D et al (2002) Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care 40:IV-3–IV-18

Hassett MJ, O’Malley AJ, Pakes JR et al (2006) Frequency and cost of chemotherapy-related serious adverse effects in a population sample of women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:1108–1117

Du XL, Osborne C, Goodwin JS (2002) Population-based assessment of hospitalizations for toxicity from chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 20:4636–4642

Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL (2000) Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol 53:1258–1267

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J (1994) Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 47:1245–1251

Hirano K, Imbens G (2001) Estimation of causal effects using propensity score weighting: an application to data on right heart catheterization. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 2:259–278

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1984) Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc 79:516–524

Rubin DB (1997) Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med 127:757–763

Joffe MM, Ten Have TR, Feldman HI, Kimmel SE (2004) Model selection, confounder control, and marginal structural models: review and new applications. Am Statistician 58:272–279

Lin DY, Psaty BM, Kronmal RA (1998) Assessing the sensitivity of regression results to unmeasured confounders in observational studies. Biometrics 54:948–963

Lamont EB, Landrum MB, Keating NL et al (2010) Differences in clinical trial patient attributes and outcomes according to enrollment setting. J Clin Oncol 28:215–221

Lamont EB, Hayreh D, Pickett KE et al (2003) Is patient travel distance associated with survival on phase II clinical trials in oncology? J Natl Cancer Inst 95:1370–1375

Muss HB, Woolf S, Berry D et al (2005) Adjuvant chemotherapy in older and younger women with lymph node-positive breast cancer. JAMA 293:1073–1081

Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione C et al (2007) Toxicity of older and younger patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: the cancer and leukemia group B experience. J Clin Oncol 25:3699–3704

Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G et al (2003) Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol 21:3580–3587

Hebert-Croteau N, Brisson J, Latreille J et al (1999) Compliance with consensus recommendations for the treatment of early stage breast carcinoma in elderly women. Cancer 85:1104–1113

Elkin EB, Hurria A, Mitra N et al (2006) Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in older women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: assessing outcome in a population-based, observational cohort. J Clin Oncol 24:2757–2764

Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF et al (2006) Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:2750–2756

Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA et al (2001) Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA 285:885–892

Leyland-Jones B, Gelmon K, Ayoub JP et al (2003) Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of trastuzumab administered every three weeks in combination with paclitaxel. J Clin Oncol 21:3965–3971

Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S et al (2001) Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 344:783–792

Tolaney SM, Barry WT, Dang CT et al (2013) A phase II study of adjuvant paclitaxel (T) and trastuzumab (H) (APT Trial) for node-negative, HER2-positive breast cancer (BC). Presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on 12 Dec 2013, Abstract #974

Warren JL, Harlan LC, Fahey A et al (2002) Utility of the SEER-Medicare data to identify chemotherapy use. Med Care 40:55–61

Bikov KA, Mullins CD, Seal B et al (2013) Algorithm for identifying chemotherapy/biological regimens for metastatic colon cancer in SEER-Medicare. Med Care. epub ahead of print

Lund JL, Sturmer T, Harlan LC et al (2013) Identifying specific chemotherapeutic agents in Medicare data: a validation study. Med Care 51:e27–e34

Burstein HJ, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Perez EA et al (2012) Choosing the best trastuzumab-based adjuvant chemotherapy regimen: should we abandon anthracyclines? J Clin Oncol 30:2179–2182

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. The collection of the California cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract N01-PC-35136 awarded to the Northern California Cancer Center, contract N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under agreement #U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and endorsement by the State of California, Department of Public Health the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred. The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Breast Cancer (NIH P50 CA089393), the CJL Foundation (to W T Barry), ACT NOW fund, Susan G. Komen for the Cure (to E P Winer and N L Keating), Fundacao para a Ciencia e Tecnologia (HMSP-ICS/0004/2011, Career Development Award) (to I Vaz-Luis) and a Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Friends Grant (to R Freedman).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freedman, R.A., Vaz-Luis, I., Barry, W.T. et al. Patterns of chemotherapy, toxicity, and short-term outcomes for older women receiving adjuvant trastuzumab-based therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 145, 491–501 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2968-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2968-9