Abstract

The purpose of this study was to better understand older women’s experience with breast cancer treatment decisions. We conducted a longitudinal study of non-demented, English-speaking women ≥ 65 years recruited from three Boston-based breast imaging centers. We interviewed women at the time of breast biopsy (before they knew their results) and 6 months later. At baseline, we assessed intention to accept different breast cancer treatments, sociodemographic, and health characteristics. At follow-up, we asked women about their involvement in treatment decisions, to describe how they chose a treatment, and influencing factors. We assessed tumor characteristics through chart abstraction. We used quantitative and qualitative analyses. Seventy women (43 ≥ 75 years) completed both interviews and were diagnosed with breast cancer; 91 % were non-Hispanic white. At baseline, women 75+ were less likely than women 65–74 to report that they would accept surgery and/or take a medication for ≥ 5 years if recommended for breast disease. Women 75+ were ultimately less likely to receive hormonal therapy for estrogen receptor positive tumors than women 65–74. Women 75+ asked their surgeons fewer questions about their treatment options and were less likely to seek information from other sources. A surgeon’s recommendation was the most influential factor affecting older women’s treatment decisions. In open-ended comments, 17 women reported having no perceived choice about treatment and 42 stated they simply followed their physician’s recommendation for at least one treatment choice. In conclusion, to improve care of older women with breast cancer, interventions are needed to increase their engagement in treatment decision-making.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The aging of the population combined with the increased use of mammography in Medicare beneficiaries has led to greater numbers of women aged 65 and older being diagnosed with breast cancer [1]. However, many breast cancer treatment trials have excluded older women, especially those with multiple comorbidities [2]. As a result, the benefits of some treatments are controversial for older women, and decision-making about breast cancer treatment may be challenging. Numerous studies have found that as women age they are less likely to receive standard treatments for breast cancer; however, variations in treatment are not fully explained by differences in patient health or tumor characteristics [3]. Meanwhile, less aggressive treatment is often associated with worse outcomes for older women [3]. Data suggest that some older women are over-treated for breast cancer based on their estimated life expectancy and tumor characteristics, while others are under-treated [4].

Despite known variations in breast cancer treatment and the potential effect on older women’s morbidity and mortality, few studies have examined how older women choose their treatments [5, 6]. Several studies have examined older women’s preferred role in treatment decisions and have found that many older women prefer a more passive role [7–13]. Yet, these findings are not consistent [14], and a more active role is associated with greater satisfaction [11, 15–17]. To better understand physicians’ breast cancer treatment recommendations for older women, we previously reviewed physician notes from sixty-five women aged 80 and older diagnosed with breast cancer. We found that many factors, such as tumor characteristics, history of breast cancer, patient age, health, transportation, family support, and the ratio of treatment benefits to risks, interact to influence physician recommendations [18]. However, this study did not examine older women’s views of treatment decision-making. To better understand older women’s perspectives, we conducted a longitudinal study of women aged 65 and older beginning at the time of breast biopsy. We interviewed women before they were told their diagnosis and then 6 months later. By identifying women before their diagnosis, we were able to assess older women’s intentions to accept breast cancer treatment which is important since intentions may affect behavior [19]. We hypothesized women ≥ 75 years would be less engaged in treatment decision-making and more reliant on family than women 65–74 years. We used both quantitative and qualitative methods to deepen our understanding of older women’s decision-making experience around breast cancer treatment.

Methods

Study design

Between August 2007 and December 2011, we interviewed English-speaking older women without dementia [determined by problem list and/or primary care physician (PCP)] at the time of breast biopsy but before women knew their results (baseline interview), and 6 months later (follow-up interview). This study was restricted to women who were diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or invasive breast cancer (confirmed by pathology reports) at follow-up.

Participants

We recruited women from breast imaging centers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Boston Medical Center. An administrator at each site provided the research staff with the names of women ≥ 65 years scheduled for breast biopsy every week. Since we aimed to include similar numbers of women ≥ 75 years as women 65–74 years, we recruited women ≥ 75 years continuously and women 65–74 years every third week. Women were contacted for this study by (1) telephone if their PCPs gave permission or (2) in the waiting room at the time of breast biopsy. Participants gave verbal informed consent. The Institutional Review Board at each site approved this study.

Data collection

Baseline

At baseline, we asked participants about their use of mammography, history of benign breast biopsy or breast cancer, and family history of breast cancer. We also assessed older women’s willingness to undergo treatment if diagnosed with breast cancer. We asked, if recommended, would you accept (1) surgery, (2) radiation therapy (use of certain type of energy to kill cancer cells), (3) chemotherapy, or (4) a medication that you had to take for 5–10 years, for treatment of a breast abnormality? Women could respond yes, no, maybe, or do not know. We also assessed participants’ educational attainment, social support (Medical Outcomes Study tangible support scale, 4 items scored on a 5 point Likert scale and summed) [20], marital status, living arrangement, cognition (Short Blessed Test, range 0–28, scores from 0 to 8 are considered within normal limits) [21], geography, and race/ethnicity. In addition, we estimated life expectancy using the Schonberg index. This index incorporates comorbidity, function, hospitalizations, tobacco use, body mass index, and scores of eight or more suggest 9-year life expectancy or less [22].

Follow-up questionnaire

Quantitative outcomes

(1) Information received At 6 months follow-up, we asked women about their perceptions of the amount of information received around breast cancer treatment (adequate, too much, too little) [23]. We also asked women if they obtained information from other sources besides their physicians (e.g., pamphlets, internet, videos, books, other people, newspaper, and television).

(2) Shared decision-making We used the Perceived Involvement in Care Index to assess patients’ perceptions of how information was shared with their surgeons and whether patients’ preferences were elicited in treatment decisions [5, 24, 25]. The index includes two scales of two questions each (patient information seeking and surgeon-initiated communication). The patient information seeking scale asks participants how much they agree (strongly disagree [1] to strongly agree [5]) with the statements, “I asked my surgeon to explain treatments and/or procedures to me in greater detail” and “I asked my surgeon a lot of questions about treatment options.” The surgeon-initiated communication scale asks participants how much they agree with the statements “my surgeon asked me about my worries about breast cancer” and “my surgeon encouraged me to give my opinions about treatment.” Responses to each item are summed for each scale (scores range from 2 to 10, higher scores indicate greater patient involvement).

(3) Factors influencing treatment decisions We asked women to report how much 11 different factors (surgeon’s recommendations, oncologist’s recommendation, advice of family, maintaining quality of life, PCP’s recommendations, health, age, faith, friend’s advice, transportation, and cost of treatment) influenced their treatment decisions from “Not at all” to “Influenced a lot” (range 0–3).

(4) Decision-making role We modified the controlled preferences scale and asked women whether they made their final treatment decision themselves, whether they shared the final treatment decision with their physicians, whether they shared the final treatment decision with their physicians and family, or whether their physicians and/or family (but not the patient) made the final treatment decision [10].

Qualitative component

We asked women to describe how they decided on each of their breast cancer treatments. We also asked “if you had to go through the process again what would you do differently?” A research assistant wrote down participants’ answers to these questions verbatim and noted any additional comments made by participants related to their experience at any point during the interviews.

Chart abstraction

We abstracted from participants’ charts information on tumor size, estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) receptivity, stage at diagnosis, and treatments received (mastectomy, lumpectomy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy). If treatments received were not available in the medical record, then we used information collected from patient report (n = 5).

Analyses

Quantitative outcomes

We used χ 2 statistics to compare sociodemographic and tumor characteristics, treatments received, and decision-making by age (65–74 and ≥ 75 years). For continuous variables, we used the two sample t-test or the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test when data were not normal. All statistical analyses used SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC.)

Qualitative Component

We used progressive coding techniques to identify themes in participants’ open-ended comments [26, 27]. Initially, one investigator (MAS) reviewed all participants’ comments to identify themes and create a code dictionary. Two investigators (BLB and LH) then used the code dictionary to recode participants’ comments. Three additional codes were added after this review. One investigator (MAS) recoded participants’ comments using the newly identified codes and reviewed the coding of the other investigators. If at least two investigators labeled a comment with a code, then the code was applied to that comment. We combined codes to identify major themes.

Results

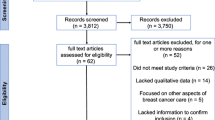

Sample population (Fig. 1)

We contacted 257 eligible women of whom 70 refused to participate. The remaining 187 women began the baseline interview but six did not complete it, eight refused follow-up, eight could not be reached for follow-up and one woman died. A total of 164 women completed both baseline and follow-up (64 % of eligible women). Of these, 70 women were diagnosed with DCIS or invasive breast cancer (43 ≥ 75 years).

Sample characteristics (Table 1)

Overall, 91 % (n = 64) of women were non-Hispanic white and 66 % (n = 46) had attended at least some college. The majority (83 %, n = 58) underwent mammography screening annually, and 23 % (n = 16) had a prior history of breast cancer. Women ≥ 75 years were significantly more likely to live alone, not be currently married, and to have less than 9-year life expectancy than women 65–74 years. Median follow-up time was 5.6 months (interquartile range 5.2–6.5 months).

At baseline, women ≥ 75 years were significantly less likely than women 65–74 years to report that they would accept surgery or take a medication for 5–10 years if diagnosed with breast disease and tended to be less likely than women 65–74 years to report that they would accept radiation and/or chemotherapy if recommended.

Tumor characteristics and treatments received (Table 2)

Sixteen women (23 %) were diagnosed with DCIS, 74 % (n = 52) with stage I–III breast cancer, 1 % (n = 1) with stage IV breast cancer, and one woman with a phyllodes tumor. The majority (94 %, n = 50 of 53) of stage I-IV tumors were ER+. For treatment of DCIS, 38 % (6 of 16) underwent mastectomy and 50 % (8 of 16) underwent lumpectomy plus radiotherapy. The five women diagnosed with DCIS with estimated life expectancy ≤9 years were treated with mastectomy or lumpectomy plus radiotherapy. For the treatment of stage I–III breast cancer, 21 % (11 of 52) of women underwent mastectomy and 71 % (37 of 52) underwent lumpectomy plus radiotherapy; the four women who did not receive radiotherapy after lumpectomy were all ≥ 75 years and had estimated life expectancy ≤ 9 years. Women ≥ 75 years were significantly less likely than women 65–74 years to take hormonal therapy for ER+ tumors [61 % (20 of 33) vs. 100 % (n = 17), p = 0.003] and to receive chemotherapy for stage I–IV breast cancers [0 (0 of 35) vs. 44 % (8 of 18), p < 0.001].

Quantitative outcomes (Table 3)

Overall, 41 % (n = 29) of women reported making their treatment decisions with their physicians and family, 34 % (n = 24) reported sharing treatment decisions with their physician (but not family), 17 % (n = 12) reported that they made their final decision on their own, and 8 % (n = 5) reported that their physician or family made their final treatment choice. There were no significant differences by age. Eighty-two percent of women (56 of 68; 2 did not respond) felt that they received adequate information about their breast cancer, while 7 % (5 of 68) reported receiving too much information, and 10 % (7 of 68) reported receiving too little information. Women ≥ 75 years (33 %, n = 14 of 42) were less likely than women 65–74 years (62 %, n = 16 of 26) to report that they obtained information from other sources besides their physicians (p = 0.02). Women ≥ 75 years were also less likely than women 65–74 years to ask their surgeons questions about their treatment options (p = 0.01) and tended to be less likely than women 65–74 years to report that their surgeons asked them about their treatment preferences (p = 0.12).

As for factors influencing treatment decisions, older women gave the highest value to their surgeon’s recommendations and then to their oncologist’s recommendations. Although transportation was only an issue for a few women, women ≥ 75 years were significantly more likely to note the importance of this factor than women 65–74 years.

Qualitative outcomes (Table 4)

Twenty-two women reported that their diagnosis made them anxious; however, six stated that they were not that concerned by their diagnosis, and four noted that the emotional impact was less due to their age. To cope with their diagnosis, women reported seeking support from friends and/or family (n = 13) and trying to think positively (n = 12).

Forty-two women noted simply following their physicians’ recommendations for at least one treatment choice. Twenty women specifically mentioned following their surgeon’s recommendation, while other women referred to their physicians collectively. Seventeen women did not perceive being given a choice about at least one treatment, and nine women commented that it would be hard to choose not to do something recommended by their physicians. Nineteen women described following their doctor’s recommendation for one treatment choice while describing a shared decision-making process for another treatment choice.

While 22 women commented that they received adequate information about their diagnosis, ten women wished they received more information about some aspect of their care. Four women felt that they could not absorb all the information provided and seven noted that they brought a “second pair of ears” to help learn the information. Thirteen women stressed the importance of asking the right questions to obtain high-quality care.

While 22 women were satisfied with their care, 13 described dissatisfaction with some aspect of care. Six women regretted an aspect of treatment and five women questioned whether they were over-treated. Four women regretted not getting a mastectomy first since they had to undergo multiple surgeries before undergoing a mastectomy.

Twenty-two women noted at least one side effect of breast cancer treatment (e.g., fatigue, change in body image, and joint pain). Ten women expressed some anxiety about recurrence and seven noted that they now had to take more pills and/or go to more medical appointments. Eight women felt their experience helped them re-evaluate life.

Discussion

Women ≥ 75 years were less likely to ask their surgeons about breast cancer treatment options, were less likely to obtain information about their treatment choices from sources beyond their physicians, and were less likely to receive standard medical therapy (chemotherapy and hormonal therapy) than women 65–74 years. While 75 % of older women reported that their final treatment decision was made in conjunction with their physicians, with or without the help of family, in open-ended comments many women felt that their treatment decision was really whether or not to follow their physicians’ recommendations rather than making an informed preference-sensitive choice between two or more options. Several women commented that they followed their physician’s recommendation for one treatment choice but engaged in a shared decision-making process for another treatment choice. These findings suggest that older women may prefer different levels of involvement in decision-making depending on the treatment decision. While many women reported feeling satisfied with their breast cancer care, several were overwhelmed by the information they received, and some questioned whether they were over-treated. These data suggest that to improve care of older women with breast cancer, interventions are needed to improve sharing of information and eliciting older women’s preferences around treatment.

Interestingly, many women in our study did not perceive having a choice about treatment or decided to simply follow their physicians’ recommendations. Although we asked participants how they made their surgical choice, few discussed making a decision between lumpectomy or mastectomy. An international consensus panel highly recommended lumpectomy for treatment of breast cancer among older women when possible [28]. Therefore, surgeons may simply be recommending lumpectomy to older women for whom they deem it appropriate rather than discussing the advantages and disadvantages of both options. However, some older women when given balanced information about both surgical options may reasonably choose to undergo mastectomy rather than lumpectomy so as not to be faced with the decision of whether or not to undergo radiotherapy, to avoid multiple surgeries, and to decrease the chance of local recurrence. In fact, several women in our study expressed frustration at having to undergo multiple surgeries only to end up ultimately needing a mastectomy. Also, despite data suggesting that radiotherapy offers only a small reduction in chance of local recurrence and no improvement in overall survival for women ≥ 70 years [29], most older women are treated with radiation after lumpectomy [4, 30]. In our study, 91 % of older women were treated with radiotherapy after lumpectomy. However, radiotherapy can cause fatigue, breast pain, and edema and increases the risk of ischemic heart disease [31, 32]. A previous study found that 59 % of women (mean age 55 years) reported hearing a discussion about both lumpectomy and mastectomy [33]. Our data suggest that discussion of both surgical treatment options may be even less common among older women. Future studies should examine surgeon discussions of breast cancer treatment options with older women.

Consistent with findings from larger studies, 88 % of women in our study diagnosed with DCIS underwent mastectomy or lumpectomy plus radiotherapy [34, 35]. However, only around one-third of cases of DCIS are thought to progress to invasive breast cancer after 10–15 years, and recurrence is less common among older women [36, 37]. To avoid overtreatment of DCIS, increasingly experts are calling for the need to identify a group of women based on life expectancy, tumor characteristics, and preferences, where DCIS could be managed through surveillance; however, no study to date has identified such a population [38]. Clinical trials are needed to test different treatment regimens for DCIS among older women, particularly those with short life expectancy, to inform treatment decisions.

Even before being diagnosed with breast cancer, women ≥ 75 years were less likely than women 65–74 years to report that they would accept recommended treatments for breast cancer. These findings suggest that choosing not to undergo a specific therapy for breast cancer may represent older women’s preferences. In fact, one recent study found that 17 % of women aged 75 and older “refused” chemotherapy that was recommended for treatment [39]. Physicians may need to become more comfortable allowing older women to choose not to receive a therapy, provided that both benefits and harms of such a choice are described.

Although study participants noted the importance of asking their physicians the right questions to ensure high-quality care, women ≥ 75 years were less likely than women 65–74 years to report asking their surgeons about their treatment options. Cohort differences, trust of medical authority, and avoidance of cognitive burden may help explain these findings [40]. Our study highlights the need for interventions to meaningfully engage older women in breast cancer treatment decision-making. Communication aids such as question lists and consultation audio-recording have been shown to increase question-asking and information recall among women of all ages [41, 42]. Decision aids may also be useful [43]. However, more data are needed to understand the types of information that older women need to ensure high-quality decision-making without information overload since several women in our study reported that they could not absorb all the information provided to them. Engaging older women, especially those with short life expectancy, in treatment decisions, is important because the benefits of some treatments may not be achieved for years, while the side effects may be more immediate. Also, perceived involvement in decision-making about breast cancer treatment has been found to be associated with better quality of life [44], and engaged patients are a key component of the Institute of Medicine’s conceptual framework of a High-Quality Cancer Care Delivery System [45].

There are known barriers to improve shared decision-making between physicians and older women with breast cancer. Despite equivalent information needs [46], physicians are less likely to discuss the likelihood of breast cancer recurrence, side effects of lymph node removal, chemotherapy rationale, and post-treatment appearance with older women [47]. Oncologists may be more direct and less likely to elicit patient preferences when communicating with older women [17]. In addition, physicians feel inadequately trained to incorporate shared decision-making into their practices [48], especially under current time constraints [49]. Therefore, interventions are needed to help physicians provide a balanced presentation of breast cancer treatment choices to older women and elicit their preferences.

To better inform older women’s treatment decisions, it would be helpful to know how often older women experience treatment side effects and the duration of symptoms. Anecdotally, 22 women in our study described some side effects of treatment. In addition, it would be helpful to understand what patient and physician factors lead to a greater exchange of information and more engaged decision-making by older women. Guidelines standardizing the information that should be provided to older women with breast cancer might improve treatment decisions and care. In addition, physicians may need to collect more information about older women’s health either as part of a geriatric assessment or in calculating patients’ estimated life expectancy to inform treatment decisions [50].

Our study has several important limitations. Because we recruited older women from one geographical location, our results may not generalize to other areas. Our sample was predominantly non-Hispanic white, and we did not collect information from proxies of older women with dementia. Also, our data are based on patients’ perceptions rather than taped interviews of physician consultations. Finally, our sample size was small limiting power for some analyses.

In summary, older women are less engaged in breast cancer treatment decision-making than younger women and tend to accept whatever treatments are recommended by their physicians. Interventions are needed to help older women engage in treatment decisions to improve the quality of their care. Ideally, older women’s breast cancer treatment decisions would consider their life expectancy, risk of recurrence, and preferences.

References

Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA (2009) Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol 27(17):2758–2765

Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA Jr (1999) Albain KS: underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med 341(27):2061–2067

Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Li D, Silliman RA, Ngo L, McCarthy EP (2010) Breast cancer among the oldest old: tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J Clin Oncol 28(12):2038–2045

Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Ngo L, Silliman RA, McCarthy EP (2012) Does life expectancy affect treatment of women aged 80 and older with early stage breast cancers? J Geriatr Oncol 3(1):8–16

Liang W, Burnett CB, Rowland JH, Meropol NJ, Eggert L, Hwang YT, Silliman RA, Weeks JC, Mandelblatt JS (2002) Communication between physicians and older women with localized breast cancer: implications for treatment and patient satisfaction. J Clin Oncol 20(4):1008–1016

Pieters HC, Heilemann MV, Maliski S, Dornig K, Mentes J (2012) Instrumental relating and treatment decision making among older women with early-stage breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 39(1):E10–E19

Beaver K, Luker KA, Owens RG, Leinster SJ, Degner LF, Sloan JA (1996) Treatment decision making in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 19(1):8–19

Bilodeau BA, Degner LF (1996) Information needs, sources of information, and decisional roles in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 23(4):691–696

Bruera E, Willey JS, Palmer JL, Rosales M (2002) Treatment decisions for breast carcinoma: patient preferences and physician perceptions. Cancer 94(7):2076–2080

Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, Sloan JA, Carriere KC, O’Neil J, Bilodeau B, Watson P, Mueller B (1997) Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA 277(18):1485–1492

Janz NK, Wren PA, Copeland LA, Lowery JC, Goldfarb SL, Wilkins EG (2004) Patient-physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision. J Clin Oncol 22(15):3091–3098

Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Leake B, Silliman RA (2004) Determinants of participation in treatment decision-making by older breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat 85(3):201–209

Petrisek AC, Laliberte LL, Allen SM, Mor V (1997) The treatment decision-making process: age differences in a sample of women recently diagnosed with nonrecurrent, early-stage breast cancer. Gerontologist 37(5):598–608

Presutti R, D’Alimonte L, McGuffin M, Chen H, Chow E, Pignol JP, Di Prospero L, Doherty M, Kiss A, Wong J et al (2013) Decisional support throughout the cancer journey for older women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer: a single institutional study. J Cancer Educ

Hack TF, Degner LF, Watson P, Sinha L (2006) Do patients benefit from participating in medical decision making? Longitudinal follow-up of women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 15(1):9–19

Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Schwartz K, Liu L, Lakhani I, Salem B, Katz SJ (2005) Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health Serv Res 40(3):745–767

Step MM, Siminoff LA, Rose JH (2009) Differences in oncologist communication across age groups and contributions to adjuvant decision outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(Suppl 2):S279–S282

Schonberg MA, Silliman RA, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER (2012) Factors noted to affect breast cancer treatment decisions of women aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 60(3):538–544

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:178–211

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL (1991) The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 32(6):705–714

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H (1983) Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 140(6):734–739

Schonberg MA, Davis RB, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER (2011) External validation of an index to predict up to 9 years mortality of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 59(8):1444–1451

Rehnberg G, Absetz P, Aro AR (2001) Women’s satisfaction with information at breast biopsy in breast cancer screening. Patient Educ Couns 42(1):1–8

Lerman CE, Brody DS, Caputo GC, Smith DG, Lazaro CG, Wolfson HG (1990) Patients’ Perceived Involvement in Care Scale: relationship to attitudes about illness and medical care. J Gen Intern Med 5(1):29–33

Mandelblatt J, Kreling B, Figeuriedo M, Feng S (2006) What is the impact of shared decision making on treatment and outcomes for older women with breast cancer? J Clin Oncol 24(30):4908–4913

Crabtree F, Miller WL (eds) (1992) Doing qualitative research. Sage, Newbury Park

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) (2000) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Eckstrom E, Feeny DH, Walter LC, Perdue LA, Whitlock EP (2013) Individualizing cancer screening in older adults: a narrative review and framework for future research. J Gen Intern Med 28(2):292–298

Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, Cirrincione CT, Berry DA, McCormick B, Muss HB, Smith BL, Hudis CA, Winer EP et al (2013) Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J Clin Oncol 31(19):2382–2387

Soulos PR, Yu JB, Roberts KB, Raldow AC, Herrin J, Long JB, Gross CP (2012) Assessing the impact of a cooperative group trial on breast cancer care in the medicare population. J Clin Oncol 30(14):1601–1607

Buchholz TA (2009) Radiation therapy for early-stage breast cancer after breast-conserving surgery. N Engl J Med 360(1):63–70

Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, Bennet AM, Blom-Goldman U, Bronnum D, Correa C, Cutter D, Gagliardi G, Gigante B et al (2013) Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med 368(11):987–998

Lee CN, Chang Y, Adimorah N, Belkora JK, Moy B, Partridge AH, Ollila DW, Sepucha KR (2012) Decision making about surgery for early-stage breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg 214(1):1–10

Gold HT, Dick AW (2004) Variations in treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ in elderly women. Med Care 42(3):267–275

Baxter NN, Virnig BA, Durham SB, Tuttle TM (2004) Trends in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst 96(6):443–448

Shamliyan T, Wang SY, Virnig BA, Tuttle TM, Kane RL (2010) Association between patient and tumor characteristics with clinical outcomes in women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2010(41):121–129

Smith BD, Haffty BG, Buchholz TA, Smith GL, Galusha DH, Bekelman JE, Gross CP (2006) Effectiveness of radiation therapy in older women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst 98(18):1302–1310

Allegra CJ, Aberle DR, Ganschow P, Hahn SM, Lee CN, Millon-Underwood S, Pike MC, Reed SD, Saftlas AF, Scarvalone SA et al (2010) National institutes of health state-of-the-science conference statement: diagnosis and management of ductal carcinoma in situ September 22–24, 2009. J Natl Cancer Inst 102(3):161–169

Kaplan HG, Malmgren JA, Atwood MK (2013) Adjuvant chemotherapy and differential invasive breast cancer specific survival in elderly women. J Geriatr Oncol 4(2):148–156

Meyer BJ, Russo C, Talbot A (1995) Discourse comprehension and problem solving: decisions about the treatment of breast cancer by women across the life span. Psychol Aging 10(1):84–103

Kinnersley P, Edwards A, Hood K, Cadbury N, Ryan R, Prout H, Owen D, Macbeth F, Butow P, Butler C (2007) Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18(3):CD004565

Pitkethly M, Macgillivray S, Ryan R (2008) Recordings or summaries of consultations for people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 16(3):CD001539

Legare F, Ratte S, Stacey D, Kryworuchko J, Gravel K, Graham ID, Turcotte S (2010) Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5:CD006732

Andersen MR, Bowen DJ, Morea J, Stein KD, Baker F (2009) Involvement in decision-making and breast cancer survivor quality of life. Health Psychol 28(1):29–37

Levit LA BE, Nass SJ (2013). In: Ganz PA (ed) Delivering high-quality cancer care, charting a new course for a system in crisis. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

Pinquart M, Duberstein PR (2004) Information needs and decision-making processes in older cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 51(1):69–80

Maly RC, Leake B, Silliman RA (2003) Health care disparities in older patients with breast carcinoma: informational support from physicians. Cancer 97(6):1517–1527

Politi MC, Studts JL, Hayslip JW (2012) Shared decision making in oncology practice: what do oncologists need to know? Oncologist 17(1):91–100

Col NF, Duffy C, Landau C (2005) Commentary–surgical decisions after breast cancer: can patients be too involved in decision making? Health Serv Res 40(3):769–779

Wildiers H, Kunkler I, Biganzoli L, Fracheboud J, Vlastos G, Bernard-Marty C, Hurria A, Extermann M, Girre V, Brain E et al (2007) Management of breast cancer in elderly individuals: recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol 8(12):1101–1115

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Christine Gordon, MPH, Maria Cecilia Griggs, MPH, and Rossana Valencia, MPH, for their work recruiting patients to this study. We are also grateful to Elena Morozov at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and Julie Ferragamo and Jane Pietrantonio at Brigham and Women’s Hospital for helping us to identify patients for this study. Written permission has been obtained from all persons named in this acknowledgment. Dr. Schonberg had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Mara Schonberg was supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging supported by the National Institute on Aging K23 [K23AG028584], The John A. Hartford Foundation, The Atlantic Philanthropies, The Starr Foundation, and The American Federation for Aging Research.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Fein-Zachary received $1,500 as a consultant for Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. in 2013. Otherwise, the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This study complies with the current laws of the United States of America.

Financial disclosure information

This research was supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging supported by the National Institute on Aging K23 [K23AG028584], The John A. Hartford Foundation, The Atlantic Philanthropies, The Starr Foundation, and The American Federation for Aging Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schonberg, M.A., Birdwell, R.L., Bychkovsky, B.L. et al. Older women’s experience with breast cancer treatment decisions. Breast Cancer Res Treat 145, 211–223 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2921-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-2921-y