Abstract

Adherence to consensus guidelines for cancer care may vary widely across health care settings and contribute to differences in cancer outcomes. For some women with breast cancer, omission of adjuvant chemotherapy or delays in its initiation may contribute to differences in cancer recurrence and mortality. We studied adjuvant chemotherapy use among women with stage II or stage III, hormone receptor–negative breast cancer to understand health system and socio-demographic correlates of underuse and delayed adjuvant chemotherapy. We used Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare linked data to examine the patterns of care for 6,678 women aged 65 and older diagnosed with stage II or stage III hormone receptor–negative breast cancer in 1994–2002, with claims data through 2007. Age-stratified logistic regression was employed to examine the potential role of socio-demographic and structural/organizational health services characteristics in explaining differences in adjuvant chemotherapy initiation. Overall utilization of guideline-recommended adjuvant chemotherapy peaked at 43% in this population. Increasing age, higher co-morbidity burden, and low-income status were associated with lower odds of chemotherapy initiation within 4 months, whereas having positive lymph nodes, more advanced disease, and being married were associated with higher odds (P < 0.05). Health system–related structural/organizational characteristics and race/ethnicity offered little explanatory insight. Timely initiation of guideline-recommended adjuvant chemotherapy was low, with significant variation by age, income, and co-morbidity status. Based on these findings, future studies should seek to explore the more nuanced reasons why older women do not receive chemotherapy and why delays in care occur.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health disparities with regard to breast cancer outcomes among elderly, low-income, rural-dwelling, and minority women are well documented [1, 2]. The extent to which these disparities result from differences in quality of cancer treatment is unknown. Barriers to delivery of high-quality cancer treatment include poor dissemination systems, provider resistance or lack of awareness of new evidence, the fragmented nature of the health care financing system, lack of effective monitoring, poor communication, and lack of incentives to change practices [3, 4].

Clinical guidelines are intended to help standardize treatment regimens across providers. Although awareness of differences in molecular subtypes of breast cancer and development of novel therapeutic and diagnostic tools [5–8] have yielded refined clinical guidelines for the management of breast cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy has remained the cornerstone of systemic therapy for patients with hormone receptor–negative disease since 1990 [9]. Joint American Society of Clinical Oncology/National Comprehensive Cancer Network (ASCO/NCCN) quality measures emphasize the importance of both administration of chemotherapy for such patients and initiation of therapy within 4 months of diagnosis [10]. Although consensus guidelines for breast cancer have focused on women under the age of 70, emerging evidence suggests clear benefits from adjuvant chemotherapy in older populations as well [11].

Variation in cancer treatment quality across patients may be related to both patient-level socio-demographic and health system-level structural/organizational characteristics. Adherence to guidelines and delivery of evidence-based care depends in part on diffusion of information across diverse health care organizations and providers [12, 13]. Thus, access to and receipt of chemotherapy in a timely fashion may vary based on where a patient receives care and corresponding structural/organizational factors of those institutions. It seems plausible that differences in structural/organizational factors, such as access to a National Cancer Institute (NCI)—designated cancer center, location of initial surgical care, and distance to chemotherapy providers, may vary across vulnerable populations that experience breast cancer disparities and may in part contribute to these disparities. To date, the degree to which these structural and organizational aspects of cancer care affect appropriate administration of chemotherapy for breast cancer and subsequent outcomes is unclear.

Although the interrelated effects of patient and structural/organizational characteristics of health services on quality of care have been explored in some diseases [14–18], these relationships have been much less systematically and comprehensively studied in breast cancer treatment. One study of North Carolina Medicaid beneficiaries showed that poor-quality breast cancer care was related to older age, living in a more rural county, receiving surgery at a smaller hospital, and living in a low-specialist density county [19].

We aimed to contribute to the existing evidence on the quality of breast cancer care in vulnerable subpopulations by examining trends in receipt and timing of initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy among Medicare-enrolled, stages II–III, hormone receptor–negative patients and by determining whether differences in structural/organizational factors, including distance to care and institutional affiliations, and select socio-demographic characteristics accounted for treatment differences.

Methods

Data source and patient population

The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)-Medicare dataset was used in the current study [20]. We identified all women in the SEER-Medicare dataset with their first or only primary breast cancer diagnosed in the years 1994–2002, with claims data through 2007. We required that patients were (1) continuously enrolled in Medicare parts A and B fee-for-service during the one-year period prior to diagnosis and at least one year post-diagnosis, or until death, whichever occurred first; (2) non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic patients (i.e., other groups were excluded because of their small numbers and insufficient power to examine racial/ethnic variation in quality of care); (3) 65 years and older at diagnosis; (4) stage II or III breast cancer at diagnosis; (5) not diagnosed with breast cancer at death or autopsy only, because these patients were not eligible for the outcome of interest, treatment, given their time of diagnosis at death; and (6) receiving breast conserving surgery or aggressive surgery/mastectomy as the first anti-cancer treatment. We further excluded women who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery, had end-stage renal disease, or were diagnosed with additional cancer within one year of the index breast cancer diagnosis, since care provided for these patients is likely different from the general breast cancer patient population. We focused our multivariate analyses on women with hormone receptor–negative cancers, defined as tumors not testing positive for estrogen or progesterone receptivity. This subgroup of patients represents women who are ineligible for endocrine therapy and for whom adjuvant chemotherapy is the cornerstone of systemic treatment, conferring a significant survival benefit [10, 21]. We refer to this group as “hormone receptor–negative” throughout, but it is important to note that also included in this definition are women with borderline or unknown hormone receptor status, since their care should be clinically similar in the absence of a positive hormone receptor test result.

Dependent variable

Initiation of any post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy within four months of diagnosis was our primary dependent variable. The 4-month time interval provides sufficient time for surgery and medical consultation and is consistent with ASCO/NCCN quality metrics [10]. Because women receive chemotherapy from various types of facilities [22], we extracted data from inpatient, carrier, outpatient, and durable medical equipment files using codes from the Healthcare Common Procedure Classification System (HCPCS), the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM), and National Drug Codes (NDC) (Table 1).

Independent variables of interest

Structural/organizational characteristics of oncologic health services included surgical facility type/ownership, bed size, teaching status, NCI cancer center designation, and American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACoSOG) affiliation, each of which was available in the SEER-Medicare data. ACoSOG membership is a proxy for organizational clinical expertise in the absence of information about Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation; in general, most ACoSOG hospitals are CoC-accredited. Distance to providers (for surgery and nearest chemotherapy provider) was calculated using zip code centroid to zip code centroid minimum distance algorithms [23–27]. We created quartiles of distance traveled to surgical providers and nearest chemotherapy providers for multivariate models.

Patient-level characteristics included race/ethnicity, age, co-morbidity, low-income status, marital status, and clinical factors that influence treatment decisions. We used SEER registry definitions of race/ethnicity [28]. Because guidelines for adjuvant chemotherapy differ by age, we stratified analyses by age group (65–69 years old versus 70 years and older) and included age as a categorical independent variable in the models of women aged 70 years and older. Co-morbidities were assessed using the NCI combined index method [29], which has been shown to be a better predictor of non-cancer mortality among breast cancer survivors than other commonly used co-morbidity measures [29]. We created quartiles of co-morbidity scores for multivariate models.

We included several covariates previously shown to influence chemotherapy and breast cancer treatment decision making, including AJCC stage of disease and histologic grade [30, 31]; marital status as a measure of social support [32]; neighborhood racial and ethnic composition (proportions of white, black, and Hispanic residents within the zip code of residence) [33, 34]; zip code-level income and education; year of diagnosis; and low-income status (measured by having any State-Buy-In (SBI) months during the study period) [28, 35, 36]. The SBI variable indicates that the state paid for supplemental insurance through its Medicaid program for individuals who met certain low-income requirements and applied for the program; thus, because many low-income people do not apply for SBI, it is a specific, but not particularly sensitive, measure of low-income status [28].

Statistical analysis

Receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy within four months of diagnosis was examined descriptively and modeled using multivariate logistic regression. Bivariate analyses compared receipt of chemotherapy and distribution of structural/organizational factors by race/ethnicity and age, using chi-squared tests [37]. In building analytic multivariate logistic models, tests were employed to determine the most appropriate variable specification (e.g., use of the continuous versus categorical forms of co-morbidity index score) for the final analytic models [38, 39]. Corrected Huber-White standard errors were reported for all models, and tests for multicollinearity among variables were conducted [39]. A P value threshold of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

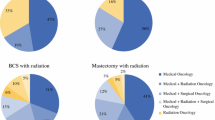

We identified 20,898 women with incident breast cancer diagnosed in 1994–2002 who met initial inclusion/exclusion criteria (i.e., all criteria except hormone receptor status). As shown in Table 2, approximately 8% of women were non-Hispanic black, 4% were Hispanic, and 88% were non-Hispanic white. The median age at diagnosis was 76.6 years. Overall, 68% were endocrine receptor positive, of whom 98% were estrogen receptor (ER) positive and 79% were progesterone receptor (PR) positive; 6,678 women were neither ER nor PR positive. Younger women and those with hormone receptor–negative tumors more often received chemotherapy.

Structural/organizational characteristics of health services were distributed unequally across racial/ethnic subpopulations (Table 3). Hispanic women were treated more often at for-profit surgical facilities (16% compared to 7% in whites and 8% in blacks; P < 0.001), and black women received surgery more often at NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers (9% compared to 2% in white women and 3% in Hispanic women; P < 0.001), ACoSOG-affiliated facilities (32% compared to 22% in white women and 15% in Hispanic women; P < 0.001), and teaching/academic health centers (62% compared to 48% in white women and 41% in Hispanic women; P < 0.001) (Table 3). Black women were less likely to live in a zip code where a chemotherapy facility was available (P < 0.001).

In multivariate models, among women who had hormone receptor–negative tumors, for whom adjuvant chemotherapy is guideline-recommended, uptake of adjuvant chemotherapy was low overall (43%), even in the latest year for which data were available. Characteristics of the surgical facility where women were treated were not predictive of initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy within four months of diagnosis (Tables 4, 5). Among women aged 70 and older (Table 5), increasing distance to a chemotherapy facility and increasing distance to the surgical facility were consistently associated with lower odds of adjuvant chemotherapy within four months, although the effect was often statistically non-significant.

In general, low-income status was associated with significantly lower odds of chemotherapy initiation at four months, despite the fact that everyone in the sample was Medicare-insured (OR: 0.49, P < 0.01 in the 65–69 age group; OR: 0.59, P < 0.01 in the 70 and older age group). Having positive lymph nodes, being diagnosed as stage III (relative to stage II), being married, and being diagnosed in later years were generally associated with significantly higher odds of chemotherapy within four months. Among women aged 70 and older only (Table 5), increasing age and greater co-morbidity were associated with significantly lower odds of chemotherapy initiation at four months (P < 0.01 for both).

Discussion

We examined the association between structural/organizational factors in health care delivery, race/ethnicity, and age and the timing of adjuvant chemotherapy among older women with breast cancer and found low overall utilization and significant variation in timing of initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy. Although the distribution of structural/organizational factors varied significantly by racial/ethnic group, this variation did not appear to correlate with disparities in chemotherapy utilization. Rather, among hormone receptor–negative women, for whom adjuvant chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab is the sole systemic therapy option, failure to receive chemotherapy within four months was associated with increasing age, earlier year of diagnosis, being unmarried, and lower-income status. Overall, it was reassuring that chemotherapy utilization appeared more likely among patients with lymph node–positive and high-grade disease and lower among those with serious co-morbidity.

Age was strongly associated with receipt of chemotherapy within four months of diagnosis, consistent with prior studies [36, 40–42]. Due to insufficient accumulation of clinical trial evidence about the effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women, clear guidelines were lacking for breast cancer patients older than 70 during this period [10]. However, many experts have argued that underrepresentation of older women in clinical trials should not preclude their receiving potentially life-prolonging breast cancer treatments [43, 44]. Moreover, clear evidence now exists indicating benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy within this patient subgroup and particularly those with hormone receptor–negative disease [11, 21, 42, 45, 46]. Our data serve to highlight the need to develop guidelines for older patients with breast cancer and provide an important benchmark for further research in this area.

The lack of a racial/ethnic disparity in the current study contrasts with findings of other work documenting significant racial/ethnic differences in chemotherapy use for breast cancer patients in select geographic regions with mixed insurance status [32, 47], but is in line with results from patients in single insurer systems, such as the military health system and Medicare [41, 48]. As such, the lack of racial/ethnic effect in the current study may be explained by the insured status of the underlying SEER-Medicare sample. Our findings may suggest that the structure and organization of health services used by minority groups with insurance do not affect receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy; alternatively, features of SEER-Medicare sampling, problems with measurement of structural/organizational variables, and/or omission of unobservable variables could explain this finding. For instance, although SEER is one of the largest national cancer registry programs in the world, SEER largely samples black and Hispanic cancer patients from specific areas (e.g., many black patients live in Detroit and Atlanta) which may not be representative of the experiences of rural-dwelling black and Hispanic persons in the United States [20]. Our subanalyses comparing health system organizational/structural factors by race/ethnicity (Table 3) support this premise, as black women in this study were more likely to be treated at larger hospitals, NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers, and academic facilities, which have been associated with improved treatment quality and/or health outcomes [18, 49–51] and which are reflective of more urban health facilities. Given the low numbers of Hispanic women in our sample, our findings may not be representative of their experiences as a whole, regardless of urban/rural residence.

Among women aged 70 and older, increasing distance to chemotherapy providers was associated with lower odds of receiving adjuvant chemotherapy at various time periods, but this effect was not always statistically significant. If distance to care presents an obstacle to elderly women, public health programs focused on providing reliable transportation options may benefit women. Given the limitations of using straight-line distances between zip code centroids, it is possible that our measures were too imprecise to detect the true effect of distance on care delivery. As such, future research should explore in more depth issues around geographic access to care as it relates to treatment planning and perceived burden of seeking oncology services among older women.

Despite the high predictive power of many variables related to tumor characteristics, co-morbidities, marital status, and income, we were unable to directly measure intent, treatment choice, or other behavioral factors that may have affected receipt of care. The decision to pursue or forgo adjuvant chemotherapy for older patients with breast cancer is complex, requiring consideration of toxicity, benefits, competing co-morbid conditions, and logistical burdens patients may face during treatment. As such, reasons for underuse of adjuvant chemotherapy are multifaceted and cannot be completely understood in a retrospective observational study of this nature. Nevertheless, older women in good health could benefit from chemotherapy [11] and thus may be systematically undertreated and unnecessarily missing out on life-sustaining therapy. Moreover, because patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy were excluded from this analysis, pre-operative use of chemotherapy is unlikely to contribute to the low levels of adjuvant chemotherapy utilization.

This study has several strengths, including its use of a large, population-based cancer registry linked with Medicare claims data and longitudinal examination of trends in breast cancer care. We have also addressed one important potential source of omitted variable bias—insurance status—by limiting our study to insured Medicare beneficiaries continuously enrolled in parts A and B fee-for-service. Despite controlling for insurance status, however, we found significantly lower odds of chemotherapy initiation within four months among low-income women, suggesting that low-income women may experience financial barriers to care that extend beyond insurance status. Future studies should employ patient interviews or focus groups with low-income women comparable to those in this study to elucidate these additional barriers; for example, lower-income, older women may be more likely to stay in the workforce than more affluent, older women, and workforce participation may conflict with keeping chemotherapy appointments.

This study extends our understanding of breast cancer treatment by (1) documenting low utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy over time among important patient subpopulations, including older, low-income, unmarried women, (2) illustrating substantial variation in timeliness of initiation of chemotherapy (which may be related to subsequent health outcomes [52]), and (3) showing potential age-related disparities in treatment among healthy elderly women with good functional status. Combined with recent data on the likely benefit of standard adjuvant chemotherapy in the older breast cancer population [11], it is possible that outcomes may be improved for a substantial number of older patients. Future studies should seek to explore the more nuanced reasons why older women do not receive chemotherapy and to better identify women at risk for under-treatment and delays in care. Moreover, older women may need better access to information about risks/benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy and improved access to chemotherapy providers (e.g., through better referral processes and transportation to chemotherapy facilities).

References

Edwards BK, Brown ML, Wingo PA, Howe HL, Ward E, Ries LAG, Schrag D, Jamison PM, Jemal A, Wu XC et al (2005) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2002, featuring population-based trends in cancer Treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 97(19):1407–1427

Lund MJ, Brawley OP, Ward KC, Young JL, Gabram SS, Eley JW (2008) Parity and disparity in first course treatment of invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 109(3):545–557

Zapka JG, Taplin SH, Solberg LI, Manos MM (2003) A framework for improving the quality of cancer care: the case of breast and cervical cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12(1):4–13

Davis D, Evans M, Jadad A, Perrier L, Rath D, Ryan D, Sibbald G, Straus S, Rappolt S, Wowk M et al (2003) The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect. BMJ 327(7405):33–35

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S et al (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMA 295(21):2492–2502

Anders C, Carey LA (2008) Understanding and treating triple-negative breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 22(11):1233–1239 discussion 1239–1240, 1243

Peppercorn J, Perou CM, Carey LA (2008) Molecular subtypes in breast cancer evaluation and management: divide and conquer. Cancer Invest 26(1):1–10

Millikan RC, Newman B, Tse CK, Moorman PG, Conway K, Dressler LG, Smith LV, Labbok MH, Geradts J, Bensen JT et al (2008) Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 109(1):123–139

NIH consensus conference (1991) Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA 265(3):391–395

Desch CE, McNiff KK, Schneider EC, Schrag D, McClure J, Lepisto E, Donaldson MS, Kahn KL, Weeks JC, Ko CY (2008) American society of clinical oncology/national comprehensive cancer network quality measures. J Clin Oncol 26(21):3631–3637

Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Theodoulou M, Mauer AM, Kornblith AB, Partridge AH, Dressler LG, Cohen HJ, Becker HP et al (2009) Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med 360(20):2055–2065

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O (2004) Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 82(4):581–629

Bowen S, Zwi AB (2005) Pathways to “evidence-informed” policy and practice: a framework for action. PLoS Med 2(7):e166

Birkmeyer NJ, Goodney PP, Stukel TA, Hillner BE, Birkmeyer JD (2005) Do cancer centers designated by the National Cancer Institute have better surgical outcomes? Cancer 103(3):435–441

Gooden KM, Howard DL, Carpenter WR, Carson AP, Taylor YJ, Peacock S, Godley PA (2008) The effect of hospital and surgeon volume on racial differences in recurrence-free survival after radical prostatectomy. Med Care 46(11):1170–1176

Morris AM, Billingsley KG, Hayanga AJ, Matthews B, Baldwin LM, Birkmeyer JD (2008) Residual treatment disparities after oncology referral for rectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 100(10):738–744

Talcott JA, Spain P, Clark JA, Carpenter WR, Do YK, Hamilton RJ, Galanko JA, Jackman A, Godley PA (2007) Hidden barriers between knowledge and behavior: the North Carolina prostate cancer screening and treatment experience. Cancer 109(8):1599–1606

Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, Demidenko E, Gottlieb D, Goodman DC (2009) Influence of NCI-cancer center attendance on mortality in lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer patients. Med Care Res Rev 66(5):542–560

Anderson RT, Kimmick GG, Camacho F, Whitmire JT, Dickinson C, Levine EA, Torti FM, Balkrishnan R (2008) Health system correlates of receipt of radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery: a study of low-income medicaid-enrolled women. Am J Manag Care 14(10):644–652

Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF (2002) Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care 40(8 Suppl):IV-3-18

Elkin EB, Hurria A, Mitra N, Schrag D, Panageas KS (2006) Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in older women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: assessing outcome in a population-based, observational cohort. J Clin Oncol 24(18):2757–2764

Warren JL, Harlan LC, Fahey A, Virnig BA, Freeman JL, Klabunde CN, Cooper GS, Knopf KB (2002) Utility of the SEER-Medicare data to identify chemotherapy use. Med Care 40(8 Suppl):1 IV-55-61

Schroen AT, Lohr ME (2009) Travel distance to mammography and the early detection of breast cancer. Breast J 15(2):216–217

Nattinger AB, Kneusel RT, Hoffmann RG, Gilligan MA (2001) Relationship of distance from a radiotherapy facility and initial breast cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 93(17):1344–1346

Shea AM, Curtis LH, Hammill BG, DiMartino LD, Abernethy AP, Schulman KA (2008) Association between the medicare modernization act of 2003 and patient wait times and travel distance for chemotherapy. JAMA 300(2):189–196

Meden T, St John-Larkin C, Hermes D, Sommerschield S (2002) MSJAMA. Relationship between travel distance and utilization of breast cancer treatment in rural northern Michigan. JAMA 287(1):111

Schroen AT, Brenin DR, Kelly MD, Knaus WA, Slingluff CL Jr (2005) Impact of patient distance to radiation therapy on mastectomy use in early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 23(28):7074–7080

Bach PB, Guadagnoli E, Schrag D, Schussler N, Warren JL (2002) Patient demographic and socioeconomic characteristics in the SEER-Medicare database applications and limitations. Med Care 40(8):IV-19-25

Klabunde CN, Legler JM, Warren JL, Baldwin LM, Schrag D (2007) A refined comorbidity measurement algorithm for claims-based studies of breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer patients. Ann Epidemiol 17(8):584–590

Andre F, Pusztai L (2006) Molecular classification of breast cancer: implications for selection of adjuvant chemotherapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 3(11):621–632

Singletary SE, Connolly JL (2006) Breast cancer staging: working with the sixth edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J Clin 56(1):37–47 quiz 50–31

Banerjee M, George J, Yee C, Hryniuk W, Schwartz K (2007) Disentangling the effects of race on breast cancer treatment. Cancer 110(10):2169–2177

Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, Brawarsky P, Keohane M, Neville BA, Williams DR (2008) Racial segregation and disparities in breast cancer care and mortality. Cancer 113(8):2166–2172

Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Lian M, Gillanders WE, Aft R (2009) The role of poverty rate and racial distribution in the geographic clustering of breast cancer survival among older women: a geographic and multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol 169(5):554–561

Bao Y, Fox SA, Escarce JJ (2007) Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differences in the discussion of cancer screening: “between-” versus “within-” physician differences. Health Serv Res 42(3 Pt 1):950–970

Bhargava A, Du XL (2009) Racial and socioeconomic disparities in adjuvant chemotherapy for older women with lymph node-positive, operable breast cancer. Cancer 115(13):2999–3008

Pagano M, Gauvreau K (2000) Principles of biostatistics, 2nd edn. Duxbury Press, Pacific Grove

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL (2008) Modern epidemiology, 3rd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Wooldridge JM (2006) Introductory econometrics—a modern approach. Thomson-Southwestern, Mason

Du XL, Key CR, Osborne C, Mahnken JD, Goodwin JS (2003) Discrepancy between consensus recommendations and actual community use of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Ann Intern Med 138(2):90–97

Du X, Goodwin JS (2001) Patterns of use of chemotherapy for breast cancer in older women: findings from Medicare claims data. J Clin Oncol 19(5):1455–1461

Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS (2006) Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24(18):2750–2756

Passage KJ, McCarthy NJ (2007) Critical review of the management of early-stage breast cancer in elderly women. Intern Med J 37(3):181–189

Wildiers H, Brain EG (2005) Adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with breast cancer: where are we? Curr Opin Oncol 17(6):566–572

Giordano SH, Fang S, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS (2008) Use of intravenous bisphosphonates in older women with breast cancer. Oncologist 13(5):494–502

Owusu C, Lash TL, Silliman RA (2007) Effect of undertreatment on the disparity in age-related breast cancer-specific survival among older women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 102(2):227–236

Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, Schrag D, Godfrey H, Hiotis K, Mendez J, Guth AA (2006) Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol 24(9):1357–1362

Enewold L, Zhou J, McGlynn KA, Anderson WF, Shriver CD, Potter JF, Zahm SH, Zhu K (2011) Racial variation in breast cancer treatment among department of defense beneficiaries. Cancer doi: 10.1002/cncr.26346

Chaudhry R, Goel V, Sawka C (2001) Breast cancer survival by teaching status of the initial treating hospital. CMAJ 164(2):183–188

Hebert-Croteau N, Brisson J, Lemaire J, Latreille J, Pineault R (2005) Investigating the correlation between hospital of primary treatment and the survival of women with breast cancer. Cancer 104(7):1343–1348

Laliberte L, Fennell ML, Papandonatos G (2005) The relationship of membership in research networks to compliance with treatment guidelines for early-stage breast cancer. Med Care 43(5):471–479

Hershman DL, Wang X, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI (2006) Delay of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation following breast cancer surgery among elderly women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 99(3):313–321

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by Dr. Wheeler’s National Research Service Award (NRSA) Predoctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, UNC at Chapel Hill, Grant No. 5-T-32 HS000032-20, and a pilot grant, Grant No. 2KR50906 (PI: Wheeler) from the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute, Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Number UL1RR025747 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wheeler, S.B., Carpenter, W.R., Peppercorn, J. et al. Predictors of timing of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with hormone receptor–negative, stages II–III breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 131, 207–216 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1717-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1717-6