Abstract

Three mutations in BRCA1 (185delAG, 5382InsC) and BRCA2 (6174delT) predominate among high risk breast ovarian cancer Ashkenazi Jewish families, with few “private” mutations described. Additionally, the spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations among high risk Jewish non Ashkenazi and non Jewish Israelis is undetermined. Genotyping by exon-specific sequencing or heteroduplex analysis using enhanced mismatch mutation analysis was applied to 250 high risk, predominantly cancer affected, unrelated Israeli women of Ashkenazi (n = 72), non Ashkenazi (n = 90), Moslem (n = 45), Christian Arabs (n = 21), Druze (n = 17), and non Jewish Caucasians (n = 5). All Jewish women were prescreened and did not harbor any of the predominant BRCA1 or BRCA2 Jewish mutations. Age at diagnosis of breast cancer (median ± SD) (n = 219) was 40.1 ± 11.7, 45.6 ± 10.7, 38.7 ± 9.2, 45.5 ± 11.4 ± and 40.7 ± 8.1 years for Ashkenazi, non Ashkenazi, Moslem, Christian, and Druze participants, respectively. For ovarian cancer (n = 19) the mean ages were 45.75 ± 8.2, 57.9 ± 10.1, 54 ± 8, 70 ± 0, and 72 ± 0 for these origins, respectively. Overall, 22 (8.8%) participants carried 19 clearly pathogenic mutations—10 BRCA1 and 9 BRCA2 (3 novel): 3 in Ashkenazim, 6 in 8 non-Ashkenazim, 6 in 7 Moslems, 2 in Druze, and 2 in non Jewish Caucasians. Only three mutations (c.1991del4, C61G, A1708E) were detected in 2 seemingly unrelated families of Moslem and non- Ashkenazi origins. There were no inactivating mutations among 55 Ashkenazi high risk breast cancer only families. In conclusion, there are no predominant recurring germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes among ethnically diverse Jewish and non Jewish high risk families in Israel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Germline mutations in the BRCA1 (MIM # 113705) and BRCA2 (MIM# 600185) genes can be detected in high risk breast/ovarian families, and serve to estimate the lifetime risk for developing these neoplasms in mutation carriers and the consequential recommendations for early detection and risk reducing surgeries [1]. More than 3,000 pathogenic mutations and sequence alterations have been reported within both genes since they were identified in the mid 1990’s (http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/). In the majority of world populations, mutations in both genes are family specific, with no obvious clustering to defined gene regions. Yet, in several populations, the spectrum of mutations is rather limited, reflecting a “founder mutation”: the Icelandic [2], the Polish [3], Russian [4], and the Norwegian [5] populations. Notably, among Ashkenazi Jews (i.e., Jews of east European ancestry) three mutations in BRCA1 (185delAG, 5382InsC) and BRCA2 (6174delT) occur frequently. These three mutations can be detected in the overwhelming majority of high risk Jewish Ashkenazi families, in about 35% of consecutive ovarian cancer cases and even in 2.5% of the general Jewish Ashkenazi population [6–9]. There are only a handful of other, family specific, mutations in Jewish Ashkenazi high risk families [10, 11]. Among the non-Ashkenazim (i.e., Jews from diverse ethnicities such as the Balkans, Iraq, Iran, North Africa, Yemen) there are also a handful of recurring mutations in both genes: 185delAG Tyr978X (BRCA1) and 8765delAG (BRCA2) [12, 13]. Yet these mutations account for only a minority of high risk, non Ashkenazi Jewish families.

While the rates of breast cancer among Arab and Druze women in Israel are lower than those for Jewish women, there is a reported increase in the rate of breast cancer diagnosis among non Jewish women in Israel since the mid 1990’s: the age standardized rate (ASR) for Jewish women was 71.1/100,000 in 1979–1981 and increased by 45.7% to 103.6/100,000 in 2000–2002. These rates for non Jewish women in Israel were 14.1/100,000 and 42.6/100,000, respectively, for the same time period, a threefold increase [14]. Furthermore, the age of diagnosis of breast cancer in Arab women is substantially younger than Jewish women in Israel, with the majority of Arab women (79%) diagnosed premenopausally and 11% being diagnosed under the age of 35 years [15]. This pattern of breast cancer morbidity of Arab women is also reported in Saudi Arabia [16]. Early age at diagnosis is suggestive of an inherited predisposition to breast cancer. However, there are only few reports on the spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among Arab-Moslem women [17–26]. Furthermore, given the Moslem Arab traditions and practices, it seemed plausible that several founder mutations may underlie inherited predisposition in that population. Even less data is available on the mutational spectra in both genes among the Druze population, a specific sect that diverged from Islam in 1017 AD and has a unique social structure hallmarked by a high rate of consanguinity, inter marriage, and an inability to join the sect or leave it [27].

The aim of the study was to define the spectrum of germline mutations in both the BRCA1 BRCA2 genes in a large set of high risk Israeli individuals of Ashkenazi, non Ashkenazi, Moslem and Christian Arab, and Druze origin.

Patients and methods

Participant identification and recruitment

The study population was recruited from among individuals counseled and tested at one of three Oncogenetics services located at the Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, the Rambam Medical Center, Haifa, or the Rivkah Ziv Medical center in Zefat, since January 1, 2000. Participants recruited were diagnosed with either breast or ovarian cancer or [in the minority of cases (n = 12), tested individuals were asymptomatic women from “high risk breast/ovarian cancer families” based on well accepted criteria] [28]. All study participants were unrelated to each other (i.e., only one patient per family was included). The study was approved by the IRB, and each patient signed an informed consent.

DNA extraction

Peripheral blood leukocyte DNA was extracted using the PUREgene kit (Gentra Inc., Minneapolis, MN), using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

Analysis for the predominant Jewish mutations in BRCA1 BRCA2 genes

Analysis for the predominant Jewish mutations in BRCA1 (185delAG 5382InsC, Tyr978X) and BRCA2 (6174delT, 8765delAG) was carried out using a PCR directed mutagenesis assay to introduce a restriction site that distinguishes between the wild type and the mutant allele, as previously described [6, 12, 13, 29].

BRCA1 genotyping

BRCA1 genotyping was performed by exon-specific amplification using flanking intronic primers and primers designed to generate slightly overlapping fragments from exon 11, as previously described [30]. No analysis for large genomic rearrangements of BRCA1 was performed.

BRCA2 genotyping

BRCA2 genotyping was performed by exon-specific amplification using flanking intronic primers and primers designed to generate slightly overlapping fragments from exon 11, as previously described [30]. In a subset of participants (some of the non Ashkenazim, the Moslem and Druze participants) BRCA2 mutational analysis was performed using heteroduplex analysis (HDA) using enhanced mismatch mutation analysis (EMMA) technique supplemented by sequencing of abnormally migrating fragments, as previously described [31]. No analysis for large genomic rearrangements of BRCA2 was performed.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Overall, there were 250 participants in the study: 72 Ashkenazim, 90 non Ashkenazi Jews, 45 Moslem Arabs, 21 non Moslem Arabs, 17 Druze, and 5 non Jewish Caucasians. There were 219 women diagnosed with breast cancer (mean age at diagnosis 43.6 ± 10.85), 19 women diagnosed with ovarian cancer (mean age at diagnosis 57.5 ± 10.7 years). Twelve women were asymptomatic with a significant family history of breast/ovarian cancer, where the affected individual could not be tested. The mean age at genotyping of these women was 45.7 ± 9.5 years. There were 133 first degree relatives with breast cancer and 16 first degree relatives with ovarian cancer. The features of the study participants are shown in Table 1.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 genotyping results

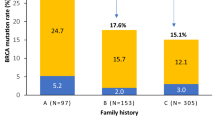

Overall, 22 individuals carried 19 clearly pathogenic mutations (19/250—6.8% rate for unique mutations detected and 22/250—8.8% for overall detection rate). There were 10 mutations in BRCA1 (including three pathogenic missense mutations) and 9 in BRCA2 (including two pathogenic missense mutations). Three novel mutations were detected (Q1721X in BRCA1, 6855del8 and 9256ins4 in BRCA2), whereas the other pathogenic mutations were previously reported. The rates of mutation carriers by ethnic origin was as follows: 3/72 among Ashkenazim (4.2%), 8/90 among non Ashkenazim (8.9%), 7/45 Moslems (15.5%), 2/17 Druze (11.7%), and 2/5 non Jewish Caucasians (40%). Three single mutations were detected in seemingly unrelated families: A1708E (BRCA1) and C61G (BRCA1) in two non Ashkenazi families, 9256ins4 (BRCA2) in 2 Arab-Moslem families. Additionally, the putatively pathogenic combination of the N550H, F486L, Y179C missense mutations (BRCA1) were detected in two non Ashkenazi families and one Moslem family. The precise mutations, their novelty and predicted effects on protein function, clinical characteristics of the proband and family history of cancer are shown in Table 2 (BRCA1) and Table 3 (BRCA2). Additional sequence alterations and their pathogenicity status, are also shown in the same tables.

Discussion

In the present study, the spectrum of germline mutations in both the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast/ovarian high risk Israeli women of diverse ethnic origin were determined. The overall rate was 8.8% for all tested individuals. For Ashkenazi Jews it seems apparent that the number of family specific mutations in both genes other than the three predominant mutations is limited. There were only 3 “private” mutations in this ethnic subset of high risk families of Ashkenazi origin, a rate of 4.2%. The most accurate factor in predicting the ability to detect these private mutations in Ashkenazim is the existence of ovarian cancer. Notably, there were no “private” mutations in Ashkenazi families even if there were multiple (up to 6) breast cancer cases diagnosed at an early age in more than one generation. These data are in line with data previously published from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, where private mutations in both genes among Ashkenazim were detected in 3 of 70 high risk Ashkenazi families (4.3%) if there were ovarian cancer cases and 1.4% for breast cancer only cases [10]. Thus, it seems reasonable to recommend full testing of the BRCA1 BRCA2 genes in Ashkenazim to high risk families with at least one case of ovarian cancer, after exclusion of the existence of the founder mutations. Clearly an autosomal dominant mode of transmission is the most likely inheritance pattern in “BRCA mutation negative” families in the present study. Thus, these families should be targeted in the attempts to find novel breast cancer susceptibility genes.

Among non Ashkenazi Jews, there were six pathogenic mutations in BRCA1 (n = 3) and BRCA2 (n = 3) genes with two mutations detected in two families—overall a mutation detection rate of 8.9%. These data on the rate of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in non Ashkenazim are in line with our own published data [29] as well as those of Palma and coworkers [11], but well below the report of Frank and co-workers of ~21.6% among Jewish non carriers of the predominant mutations [32]. Thus, although full mutational analysis of BRCA1 BRCA2 in non Ashkenazi Jews is warranted, clearly other genes underlie the majority of inherited predisposition to breast/ovarian cancer in this subset of individuals.

Of the 19 pathogenic mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 described herein, 6 were detected among in 7 individuals of 45 Arab Moslem (Palestinian) women (15.5%) and 2 among 17 Druze individuals (11.7%). This is the most comprehensive analysis published to date on high risk families of these origins. Overall, there are only a handful of germline mutations among Moslem women that were reported world-wide, with a paucity of data about the Palestinian population: an inactivating mutation (E1373X) in BRCA1 [18] another clearly pathogenic mutation (2482delGACT) in BRCA2 [17] and several missense mutations of unknown pathogenic significance in our own previously published series [29].

The data presented in this study, combined with these previous reports among Palestinians, signify that despite theoretical predictions and assumptions that the spectrum of mutations in BRCA1 BRCA2 among Palestinians is limited, the reality is that like most world populations full analysis of both genes is warranted in the appropriate clinical setting. Notably, all but one of the mutations was detected only once. This lack of an apparent founder mutation in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in the Arab (Moslem, Christian, and Druze) population is intriguing. Despite the fact that the Druze sect is a clear example of a genetic isolate, there are no predominant or recurring mutations among high risk families of Druze (or Moslem) origin. Several reasons could account for the low rate of detection of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in these ethnic populations: low threshold of family history at selection, inadequate selection criteria, phenocopies that were analyzed or the reduced rate of BRCA1 BRCA2 carriership predicted in societies where consanguineous marriages have been practiced [33].

The limitations of the present study should be outlined: the methodology for detecting BRCA2 mutations (EMMA) may have missed existing mutations. Notably EMMA has been shown to be a similar sensitivity and provide the same mutation rate and accuracy as DHPLC in a large series (n = 1525) of genotyped individuals [34]. The existence of large genomic rearrangement was not excluded. However, at least among Ashkenazim, the contribution of such genomic events to the overall burden of inherited predisposition to breast cancer is limited [11, 35]. Moreover, the representation of the non Jewish populations may have been suboptimal, as these represent families from three medical centers, which may under represent some sects in the non Jewish populations in Israel.

In conclusion, there are no recurring mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes among high risk Moslem Israeli, Druze and non Ashkenazi Jews. Thus, in order to evaluate the putative contribution of both genes to inherited predisposition to breast cancer of individuals from these ethnicities, full mutational analysis is warranted. The existence of novel breast cancer genes is supported by the extreme paucity of “private” mutations in BRCA1 BRCA2 among high risk Ashkenazi families.

References

Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Feldman GL (2010) Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer due to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Genet Med 12(5):245–259

Thorlacius S, Struewing JP, Hartge P, Olafsdottir GH, Sigvaldason H, Tryggvadottir L, Wacholder S, Tulinius H, Eyfjörd JE (1998) Population-based study of risk of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA2 mutation. Lancet 352(9137):1337–1339

Górski B, Cybulski C, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Jakubowska A, Stawicka M, Gozdecka-Grodecka S, Szwiec M, Urbański K, Mituś J, Marczyk E, Dziuba J, Wandzel P, Surdyka D, Haus O, Janiszewska H, Debniak T, Tołoczko-Grabarek A, Medrek K, Masojć B, Mierzejewski M, Kowalska E, Narod SA, Lubiński J (2005) Breast cancer predisposing alleles in Poland. Breast Cancer Res Treat 92(1):19–24

Sokolenko AP, Mitiushkina NV, Buslov KG, Bit-Sava EM, Iyevleva AG, Chekmariova EV, ESh Kuligina, Ulibina YM, Rozanov ME, Suspitsin EN, Matsko DE, Chagunava OL, Trofimov DY, Devilee P, Cornelisse C, Togo AV, Semiglazov VF, Imyanitov EN (2006) High frequency of BRCA1 5382insC mutation in Russian breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 42(10):1380–1384

Heimdal K, Maehle L, Apold J, Pedersen JC, Møller P (2003) The Norwegian founder mutations in BRCA1: high penetrance confirmed in an incident cancer series and differences observed in the risk of ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer 39(15):2205–2213

Abeliovich D, Kaduri L, Lerer I, Weinberg N, Amir G, Sagi M, Zlotogora J, Heching N, Peretz T (1997) The founder mutations 185delAG and 5382insC in BRCA1 and 6174delT in BRCA2 appear in 60% of ovarian cancer and 30% of early-onset breast cancer patients among Ashkenazi women. Am J Hum Genet 60(3):505–514

Tobias DH, Eng C, McCurdy LD, Kalir T, Mandelli J, Dottino PR, Cohen CJ (2000) Founder BRCA 1 and 2 mutations among a consecutive series of Ashkenazi Jewish ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 78(2):148–151

Warner E, Foulkes W, Goodwin P, Meschino W, Blondal J, Paterson C, Ozcelik H, Goss P, Allingham-Hawkins D, Hamel N, Di Prospero L, Contiga V, Serruya C, Klein M, Moslehi R, Honeyford J, Liede A, Glendon G, Brunet JS, Narod S (1999) Prevalence and penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in unselected Ashkenazi Jewish women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 91(14):1241–1247

Hartge P, Struewing JP, Wacholder S, Brody LC, Tucker MA (1999) The prevalence of common BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among Ashkenazi Jews. Am J Hum Genet 64(4):963–970

Kauff ND, Perez-Segura P, Robson ME, Scheuer L, Siegel B, Schluger A, Rapaport B, Frank TS, Nafa K, Ellis NA, Parmigiani G, Offit K (2002) Incidence of non-founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in high risk Ashkenazi breast and ovarian cancer families. J Med Genet 39(8):611–614

Palma MD, Domchek SM, Stopfer J, Erlichman J, Siegfried JD, Tigges-Cardwell J, Mason BA, Rebbeck TR, Nathanson KL (2008) The relative contribution of point mutations and genomic rearrangements in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in high-risk breast cancer families. Cancer Res 68(17):7006–7014

Shiri-Sverdlov R, Gershoni-Baruch R, Ichezkel-Hirsch G, Gotlieb WH, Bruchim Bar-Sade R, Chetrit A, Rizel S, Modan B, Friedman E (2001) The Tyr978X BRCA1 mutation in Non-Ashkenazi Jews: occurrence in high-risk families, general population and unselected ovarian cancer patients. Community Genet 4(1):50–55

Lerer I, Wang T, Peretz T, Sagi M, Kaduri L, Orr-Urtreger A, Stadler J, Gutman H, Abeliovich D (1998) The 8765delAG mutation in BRCA2 is common among Jews of Yemenite extraction. Am J Hum Genet 63(1):272–274

Tarabeia J, Baron-Epel O, Barchana M, Liphshitz I, Ifrah A, Fishler Y, Green MS (2007) A comparison of trends in incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer, incidence to mortality ratio and stage at diagnosis between Arab and Jewish women in Israel, 1979–2002. Eur J Cancer Prev 16(1):36–42

Nissan A, Spira RM, Hamburger T, Badriyyah M, Prus D, Cohen T, Hubert A, Freund HR, Peretz T (2004) Clinical profile of breast cancer in Arab and Jewish women in the Jerusalem area. Am J Surg 188:62–67

Ibrahim EM, al-Mulhim FA, al-Amri A, al-Muhanna FA, Ezzat AA, Stuart RK, Ajarim D (1998) Breast cancer in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Med Oncol 15:241–247

El-Harith el HA, Abdel-Hadi MS, Steinmann D, Dork T (2000) BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients from Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 23:700–704

Kadouri L, Bercovich D, Elimelech A, Lerer I, Sagi M, Glusman G, Shochat C, Korem S, Hamburger T, Nissan A, Abu-Halaf N, Badrriyah M, Abeliovich D, Peretz T (2007) A novel BRCA-1 mutation in Arab kindred from east Jerusalem with breast and ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer 7:14

Atoum MF, Al-Kayed SA (2004) Mutation analysis of the breast cancer gene BRCA1 among breast cancer Jordanian females. Saudi Med J 25(1):60–63

Troudi W, Uhrhammer N, Sibille C, Dahan C, Mahfoudh W, Bouchlaka Souissi C, Jalabert T, Chouchane L, Bignon YJ, Ben Ayed F, Ben Ammar Elgaaied A (2007) Contribution of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to breast cancer in Tunisia. J Hum Genet 52(11):915–920

Eachkoti R, Hussain I, Afroze D, Aejazaziz S, Jan M, Shah ZA, Das BC, Siddiqi MA (2007) BRCA1 and TP53 mutation spectrum of breast carcinoma in an ethnic population of Kashmir, an emerging high-risk area. Cancer Lett 248(2):308–320

Troudi W, Uhrhammer N, Romdhane KB, Sibille C, Amor MB, Khodjet El Khil H, Jalabert T, Mahfoudh W, Chouchane L, Ayed FB, Bignon YJ, Elgaaied AB (2008) Complete mutation screening and haplotype characterization of BRCA1 gene in Tunisian patients with familial breast cancer. Cancer Biomark 4(1):11–18

Uhrhammer N, Abdelouahab A, Lafarge L, Feillel V, Ben Dib A, Bignon YJ (2008) BRCA1 mutations in Algerian breast cancer patients: high frequency in young, sporadic cases. Int J Med Sci 5(4):197–202

Moattar T, Kausar T, Aban M, Khan S, Pervez S (2006) Medullary carcinoma of breast with a novel germline mutation 1123T>G in exon 11 of BRCA1. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 16(9):606–607

Liede A, Malik IA, Aziz Z, Rios Pd Pde L, Kwan E, Narod SA (2002) Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to breast and ovarian cancer in Pakistan. Am J Hum Genet 71(3):595–606

Rashid MU, Zaidi A, Torres D, Sultan F, Benner A, Naqvi B, Shakoori AR, Seidel-Renkert A, Farooq H, Narod S, Amin A, Hamann U (2006) Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Pakistani breast and ovarian cancer patients. Int J Cancer 119(12):2832–2839

Nissim D (2003) The Druze in the Middle East: their faith, leadership, identity and status. Sussex Academic Press, Brighton, pp 227. ISBN: 978-1903900369

Lynch HT, Watson P, Tinley S, Snyder C, Durham C, Lynch J, Kirnarsky Y, Serova O, Lenoir G, Lerman C, Narod SA (1999) An update on DNA-based BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic counseling in hereditary breast cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 109:91–98

Shiri-Sverdlov R, Oefner P, Green L, Baruch RG, Wagner T, Kruglikova A, Haitchick S, Hofstra RM, Papa MZ, Mulder I, Rizel S, Bar Sade RB, Dagan E, Abdeen Z, Goldman B, Friedman E (2000) Mutational analyses of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi Jewish women with familial breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mutat 16(6):491–501

Soegaard M, Kjaer SK, Cox M, Wozniak E, Høgdall E, Høgdall C, Blaakaer J, Jacobs IJ, Gayther SA, Ramus SJ (2008) BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence and clinical characteristics of a population-based series of ovarian cancer cases from Denmark. Clin Cancer Res 14(12):3761–3767

Houdayer C, Moncoutier V, Champ J, Weber J, Viovy JL, Stoppa-Lyonnet D (2010) Enhanced mismatch mutation analysis: simultaneous detection of point mutations and large scale rearrangements by capillary electrophoresis, application to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Methods Mol Biol 653:147–180

Frank TS, Deffenbaugh AM, Reid JE, Hulick M, Ward BE, Lingenfelter B, Gumpper KL, Scholl T, Tavtigian SV, Pruss DR, Critchfield GC (2002) Clinical characteristics of individuals with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: analysis of 10,000 individuals. J Clin Oncol 20(6):1480–1490

Denic S, Al-Gazali L (2002) Breast cancer, consanguinity, and lethal tumor genes: simulation of BRCA1/2 prevalence over 40 generations. Int J Mol Med 10(6):713–719

Moncoutier V, Castera L, Tirapo C, Michaux D, Remon MA, Laugé A, Rouleau E, de Pauw A, Buecher B, Gauthier-Villars M, Viovy JL, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Houdayer C (2010) EMMA, a cost- and time-effective diagnostic method for simultaneous detection of point mutations and large-scale genomic rearrangements: application to BRCA1 and BRCA2 in 1,525 patients. Hum Mutat (submitted)

Distelman-Menachem T, Shapira T, Laitman Y, Kaufman B, Barak F, Tavtigian S, Friedman E (2009) Analysis of BRCA1/BRCA2 genes’ contribution to breast cancer susceptibility in high risk Jewish Ashkenazi women. Fam Cancer 8(2):127–133

Kaufman B, Laitman Y, Carvalho MA, Edelman L, Menachem TD, Zidan J, Monteiro AN, Friedman E (2006) The P1812A and P25T BRCA1 and the 5164del4 BRCA2 mutations: occurrence in high-risk non-Ashkenazi Jews. Genet Test 10(3):200–207

Tavtigian SV, Deffenbaugh AM, Yin L, Judkins T, Scholl T, Samollow PB, de Silva D, Zharkikh A, Thomas A (2006) Comprehensive statistical study of 452 BRCA1 missense substitutions with classification of eight recurrent substitutions as neutral. J Med Genet 43:295–305

Katagiri T, Kasumi F, Yoshimoto M, Nomizu T, Asaishi K, Abe R, Tsuchiya A, Sugano M, Takai S, Yoneda M, Fukutomi T, Nanba K, Makita M, Okazaki H, Hirata K, Okazaki M, Furutsuma Y, Morishita Y, Iino Y, Karino T, Ayabe H, Hara S, Kajiwara T, Houga S, Shimizu T, Toda M, Ymazaki Y, Uchida T, Kunimoto K, Sonoo H, Kurebayashi J-I, Shimtsuma K, Nakamura Y, Miki Y (1998) High proportion of missense mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Japanese breast cancer families. J Hum Genet 43(1):42–48

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laitman, Y., Borsthein, R.T., Stoppa-Lyonnet, D. et al. Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in ethnically diverse high risk families in Israel. Breast Cancer Res Treat 127, 489–495 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-1217-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-1217-0