Abstract

Pathogenic microbes rapidly develop resistance to antibiotics. To keep ahead in the “microbial war”, extensive interdisciplinary research is needed. A primary cause of drug resistance is the overuse of antibiotics that can result in alteration of microbial permeability, alteration of drug target binding sites, induction of enzymes that destroy antibiotics (ie., beta-lactamase) and even induction of efflux mechanisms. A combination of chemical syntheses, microbiological and biochemical studies demonstrate that the known critical dependence of iron assimilation by microbes for growth and virulence can be exploited for the development of new approaches to antibiotic therapy. Iron recognition and active transport relies on the biosyntheses and use of microbe-selective iron-chelating compounds called siderophores. Our studies, and those of others, demonstrate that siderophores and analogs can be used for iron transport-mediated drug delivery (“Trojan Horse” antibiotics) and induction of iron limitation/starvation (Development of new agents to block iron assimilation). Recent extensions of the use of siderophores for the development of novel potent and selective anticancer agents are also described.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The development of resistance to antibiotics is now very common and considerable research effort should be devoted to keeping us one step ahead in the perpetual war against microbial infection. While resistance to antimicrobial agents is inevitable, overuse of antibiotics has exacerbated the problem by inducing microbes to alter permeability barriers and drug target binding sites, biosynthesize enzymes such as beta-lactamases, that destroy antibiotics, and evolve efflux mechanisms to actively pump antibiotics out of the target cell before they cause irreparable damage (Levy 1992). Still, even while microbes exert such combined efforts to circumvent uptake and action of antibiotics, they must assimilate nutrients for survival. One of the most essential of these nutrients is iron. Interestingly, microbes most often rely on sequestration of ferric iron [Fe(III)] even though it is inherently insoluble in aqueous and organic media, hence also in lipid-like and membrane barriers. Herein, we summarize efforts to exploit microbial iron transport mechanisms for the design, syntheses and study of novel antibiotics. The focus will be two fold and emphasize the potential of iron transport-mediated drug delivery and possible implications of limiting iron uptake by microbes. Extensions of the chemistry developed during these studies also has potential for the discovery of other therapeutic agents, including anticancer compounds and diagnostics.

To sequester physiologically essential iron, microbes use three general mechanisms (Winkelmann and van der Helm 1987; Hider 1984; Guerinot 1994): (1) chelation and active transport, (2) low affinity ferric transport directly from host iron sources, and (3) ferric ion [Fe(III)] reduction to Fe(II) prior to transport. In the first and most common iron transport mechanism, microbes synthesize and secrete specific low-molecular weight iron chelators called siderophores. Once secreted, the siderophores bind extracellular ferric iron from the media or host with binding constants often ranging from 1030 to 1052, depending on the nature of the ligands. Most siderophores contain three bidentate iron binding moieties (most often hydroxamates, catechols and/or alpha-hydroxy carboxylic acids) attached to a single platform to maximize binding efficiency. The biosynthesis of siderophores is up-regulated under iron deficient conditions, including those experienced during infection of a host. Competition for iron between a host and pathogenic microbes is one of the most important factors in determining the course of a microbial infection (Payne 1988; Bullen 1987). In many infections, siderophores produced by microorganisms are even able to acquire iron from the host’s storage proteins, lactoferrin or transferrin. Most microbes express specific outer membrane proteins to recognize the iron complexes of their siderophores and sometimes even evolve receptors for siderophore-iron complexes made by other microbes to insure a competitive growth advantage. Recognition is followed by initiation of specific protein-mediated active transport processes (Ferguson et al. 2002, 1998). After siderophore-iron complex uptake, release of the iron for storage or metabolic use proceeds through either enzymatic degradation of the siderophore or, more commonly, through reduction of the tightly bound Fe(III) to Fe(II) which has a lower affinity for the siderophores.

Siderophore-mediated drug delivery (“Trojan Horse” antibiotics)

Siderophore-mediated drug transport in bacteria and fungi has been demonstrated in our laboratories (Miller and Malouin 1993; Miller et al. 1993) and others (Budzikiewicz 2004). Furthermore, nature has provided examples of iron transporters used to deliver toxic substances to bacteria in the albomycins (Benz et al. 1982; Benz 1984, 1984, 1984 Paulsen et al. 1987), ferrimycin A1 (Rogers 1987; Neilands and Valenta 1985), and the salmycins (Vertesy et al. 1995), recently synthesized for the first time in our laboratory (Dong et al. 2002). The following discussion will not be all inclusive, but will highlight design, syntheses and studies of siderophore-drug conjugates. The studies included detailed demonstration of the ability to actively transport drugs to targeted pathogens by microbial iron assimilation mechanisms. Recent reviews also emphasize the importance of siderophores for virulence and the potential of the “Trojan Horse” approach (Miethke and Marahiel 2007).

Studies have demonstrated that the use of siderophore-mediated drug delivery for the development of new antibacterial agents is feasible and effective. In an early example, E-0702, a semisynthetic iron-chelating antipseudomonal cephalosporin derivative, was proposed to be incorporated into microbial cells by the tonB-dependent iron transport system (Watanabe et al. 1987; Katsu et al. 1982). Subsequently, many other catechol (e.g., LB10522 and several conjugates reported by the HKI) and hydroxypyridone-substituted cephalosporin derivatives were prepared and shown to have significant antipseudomonal activity, presumably because of iron chelation facilitated uptake by otherwise resistant microbes (Heinisch et al. 2002; Jaynes et al. 1996)  .

.

Albomycin is actively carried into Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial cells by iron transport processes and, once in the cells, the thionucleoside analog is enzymatically released to exert its toxic effect (Braun et al. 1983). Intracellular release of the aminoglycoside-like antibiotic from salmycins has been postulated to involve hydrolysis of the hexopyranose linker. The overall result was natural evolution of a siderophore-drug conjugate with outstanding microbial selectivity and activity (MIC = 0.01 μg/mL) against Staphylococci and Streptococci, including multidrug resistant strains! Taken together, these examples of siderophore-linker-drug combinations suggest that it is possible to use iron transport-mediated processes for microbe-selective drug delivery.

Synthetic and mode of action studies in our laboratories and others indicated that the rational design and syntheses of siderophore antibacterial agent-conjugates (“Trojan Horse” antibiotics) are possible (Roosenberg et al. 2000). For example, we have reported the only synthesis of salmycins and analogs (Dong et al. 2002). We previously reported the design, syntheses and antimicrobial activity of unnatural carbacephalosporin conjugates (1 and 2) with separate hydroxamic acid-based and catechol-based siderophore components (Dolence et al. 1990, 1991a; Mckee et al. 1991; Miller 1989). As expected, detailed biological assays revealed that the hydroxamate- and catechol-containing conjugates utilized different outer membrane receptor proteins to initiate cellular entry of Fhu and cir receptors, respectively, (Dolence et al. 1991b; Minnick et al. 1992; Brochu et al. 1992). Control experiments with the siderophore components alone indicated that the siderophores were recognized by and assimilated by the wild-type target bacteria, but not by the respective transport deficient mutants, thus confirming involvement in iron assimilation. Once in the cell, the ß-lactam drug conjugates were found to directly interact with penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), induce cell lysis and inhibit growth of the parent organism. In vitro studies suggested that strains without appropriate outer membrane receptor proteins (as determined by outer membrane protein analysis) for 1 or 2 were rapidly selected. While these strains were resistant to the individual conjugates, they were still susceptible to the alternate conjugates. Further, collaborative studies revealed that the selected mutants were not pathogenic in vivo, presumably since the mutants lack a full complement of iron assimilation mechanisms and therefore are at a growth disadvantage in serum. Additionally, combined therapy using hydroxamate and catechol-carbacephalosporin conjugates 1 and 2 resulted in more effective inhibition of microbial growth than the individual conjugates alone. Based on these interesting observations we postulated that combination of catechol and hydroxamate components into a single conjugate structure might promote recognition and transport by multiple siderophore assimilation processes and minimize the development of resistance by selection of mutants defective in one type of siderophore recognition. Any multiply resistant strains would be especially prone to iron starvation. Indeed, our first synthetic mixed hydroxamate- and catechol-containing siderophore-like conjugates (3 and 4) of carbacephalosporins can use multiple transport processes in E. coli and are not only effective against the parent strains, but also the individual mutants selected from prior incubation with conjugates 1 and 2 (Ghosh et al. 1996). Moreover, the new “mixed ligand” conjugates have more diverse activity. For example, when tested against strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, 3 had MIC values of 2–8 μg/mL, unexpectedly potent levels for a beta-lactam (MIC values for Lorabid, the drug component of the conjugate, against the same strains were >128 μg/mL). Incubation of 3 with mutants previously isolated from the exposure of E. coli X580 (gift from Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN) to hydroxamate conjugate 1, and shown to be missing the outer membrane triornithylhydroxamate receptor protein (FhuA), resulted in significant inhibition of growth. The effect of 4 on this mutant was less dramatic. Repetition of the growth inhibition/delay studies with E. coli X580 in the presence of 10 μM of 3 or 4 and EDDHA [ethylenediamine bis(o-hydroxyphenylacetic acid] to simulate an iron deficient medium similar to mammalian serum, resulted in complete inhibition of growth in the presence of 3.

These fascinating results suggested that conjugate 3 may use alternate receptor and/or transport systems compared to the original conjugates 1 and 2, while 4, which contains five rather than the usual three bidentate ligands, might not be as versatile. Indeed, further studies with previously selected and characterized mutants indicate a dependence of the activity of 3 on tonB, cir and fiu. Thus, the new mixed ligand siderophore conjugate 3 is able to utilize a variety of active transport processes to deliver antibiotics to and inhibit the growth of parent strains of pathogenic bacteria. Subsequently selected iron transport deficient mutants are iron starved and, based on precedent with 1 and 2, might not be as virulent.

Complimentary disc diffusion assays are often performed as well as the liquid kinetic growth inhibition studies (Fig. 1) with representative pathogens and each of the siderophore conjugates synthesized. In some cases, separate colonies could be observed within inhibitory zones provided by some conjugates whereas a two-zone phenomena could be observed with other conjugates. Again, isolation and studies of these separate colonies revealed that they were mutants lacking specific siderophore receptor(s) and/or transport capabilities. We now know that there is a relationship between the number of individual colonies within the inhibitory zone or the type of inhibitory zone observed and the number of ferri-complex receptors used by a given conjugated drug. For example, a two-zone phenomena correlated with the capability to use two ferri-complex receptors for entry into E. coli cells. We now also know that a lower frequency of resistance is a very good indicator of multiple receptor-mediated entry occurring simultaneously. This observation is very important and validated the use of mixed siderophore ligands in conjugates, such as 3, or use of a mixture of conjugates (such as 1 plus 2) to achieve greater inhibitory activity concomitantly with a lower frequency of resistance. Also, as discussed above, in the case of siderophore conjugates, the development of resistance should be viewed with much more latitude and vision since even one single type of mutation selects strains that are not able to survive or grow in an in vivo environment where competition for iron availability is crucial for pathogenesis.

Synthetic siderophore-drug conjugates, growth curves and outer membrane protein (OMP) profiles of wild-type E. coli X580 and selected “non pathogenic” mutants “resistant to” 1 (1R) and 2 (2R) or the combination of 1 and 2 (1&2R, “double mutant”) because of missing outer membrane siderophore receptors

To further demonstrate the mode of action of these antibiotic siderophore conjugates, we reduced the “essential” C=C of the drug (Lorabid) and determined that neither the “reduced Lorabid” nor any of its conjugates retained any antibiotic activity. In fact, the reduced conjugate was a growth promoter since the antibiotic itself is inactive. This simple study was very important as it illustrated that the antibiotic activity of conjugates cannot just be attributed to carrying anything into a targeted microbe, but, at least for “drug delivery” the “warhead” of the conjugate must be able to hit a target.

We have synthesized and studied many other siderophore-drug conjugates and found that most that do not incorporate beta-lactam antibiotics are not very antimicrobially effective, even though active transport through the outer membrane still occurs. This suggests a need for release of the drug at some point, presumably so that the drug can diffuse to the proper site of action. Again, nature seems to have addressed this situation. Albomycin is only active against microbes that possess a serine peptidase to cleave the thionucleoside moiety from the siderophore peptide (Benz 1984, 1984, 1984; Braun and Endriß 2007). Based on our earlier syntheses and studies of the salmycins, we hypothesize that reductive removal of iron from the trihydroxamate siderophore may trigger release of the pendant amino glycoside antibiotic portion. As shown in Fig. 2, iron release generates free hydroxamic acids or hydroxamates, one of which is perfectly poised to anchimerically assist drug release by an intramolecular attack at the ester-drug linkage. The potential of generalizing this and other reductive-triggered drug release process in the design of new siderophore-drug conjugates is under active investigation in our laboratories.

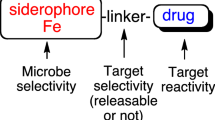

Research related to the use of siderophores to smuggle drugs into pathogenic microbes is becoming extensive, and justifiably so since new antibiotics are so desperately needed. Perhaps antibiotics of the future can be rationally designed to be microbe-selective based on the generalized structure shown below (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, other methods of developing antibiotics based on the amazing importance of microbial dependence on iron should be considered. At least two other methods are obvious: (a) limiting microbial iron uptake and (b) taking advantage of the actual processing steps required by microbes to use iron once it is assimilated. A brief discussion of the potential of iron limitation follows.

Limiting microbial iron uptake: towards the development of novel antituberculosis agents

Many studies suggest that microbes compete for limited iron by selective biosyntheses of siderophores and selective siderophore transport and some studies indicate that siderophores from one type of organism can antagonize the growth of other microbes. Inhibition of siderophore biosynthesis has become a target of intense research. Related studies in mycobacteria, notably M. tuberculosis, are especially exciting.

Mycobacterial iron acquisition is essential for pathogenicity, and provides an attractive target for the development of TB-selective antibiotics. Chelation and low affinity transport mechanisms have been found to be operative in mycobacteria (Snow 1970). Acquisition of iron by mycobacteria depends on the presence of soluble Fe(III) complexes generated from host iron sources. These solubilized Fe(III)-complexes must then be sequestered by the mycobacteria to initiate iron transport across the cell envelope to be utilized immediately or stored for future metabolic need. Iron transport mechanisms have been proposed involving media soluble ferric-exochelins and/or carboxymycobactins and membrane bound mycobactins. Additional involvement of membrane bound proteins also has been examined (Vergne et al. 2000; Wheeler and Ratledge 1994; Ratledge 1984, 1987, 2004). The figure below, updated by us and adapted from the one developed by Ratledge, represents the proposed modes of iron transport employed by mycobacteria. Additional details of the iron transport processes in mycobacteria are provided below to set the stage for our proposed use of mycobacterial iron assimilation processes for the design and syntheses of novel antimycobacterial agents. The involvement of two structurally distinct peptide-based siderophores (media/aqueous soluble and membrane soluble) is unique for microbial iron transport (Fig. 4).

Mycobactins have been found in nearly all types of mycobacteria. Different strains of mycobacteria produce mycobactins with differing substructures, but all mycobactins have the same general structure shown above. The key features of the mycobactin structure are the two hydroxamic acids and the 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-Δ2-1,3-oxazoline residue which act as iron-chelating components. Mycobactins are lipophilic, water insoluble siderophores (iron complex K s ~ 1036), and are membrane associated iron chelators as determined by electron microscopy (Ratledge et al. 1982). Ratledge demonstrated their involvement in iron transport in M. smegmatis through radioactive Fe-mycobactin uptake (Ratledge 1971; Ratledge and Marshall 1972). Their water insolubility precludes their use as extracellular iron chelators. Exochelin MS (Sharman et al. 1995a) is a water-soluble iron binding peptide-based siderophore produced by M. smegmatis (Macham and Ratledge 1975; Macham et al. 1977). Exochelins have been isolated from M. bovis (Macham and Ratledge 1975; Macham et al. 1975), M. avium (McCready and Ratledge 1977), M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, M. paratuberculosis (Barclay and Ratledge 1983), M. vaccae (Messenger et al. 1986), M. tuberculosis, M. smegmatis, M. neoaurun (Sharman et al. 1995b), and M. africanum. Exochelin MN, isolated from M. neoaurum, can also mediate iron transport in M. leprae cells, the causative agents of leprosy (Ratledge et al. 1982). The fact that other exochelins do not mediate iron uptake in M. leprae suggests a specific uptake mechanism involving exochelin MN. An iron transport mechanism was proposed in which the exochelins act as extracellular iron scavengers, migrate to the cell wall and transfer iron to the mycobactins (Stephenson and Ratledge 1978, 1979; Morrison 1995). The presence of free amine groups in exochelins suggested that iron binding might be dependent on the protonation state of the amine. In a collaborative study with Prof. Crumbliss at Duke University and Prof. C. Ratledge at the University of Hull, UK, we reported the first synthesis and studies of exochelin MN that allowed us to determine that iron binding was indeed pH dependent and proceeds by the detailed process described in our related publication (Dhungana et al. 2003).

The critical dependence of the growth and virulence of mycobacteria, including M. tuberculosis, on iron assimilation has generated strong interest in utilizing this potential “Achilles heel” for the development of new anti-TB agents. The known anti-TB drug, p-aminosalicylate (PAS), was originally proposed as an inhibitor of folic acid biosynthesis. Yet, it is relatively inactive against other bacteria. Brown and Ratledge showed that PAS inhibits iron uptake in M. smegmatis by 50% at 0.33 mM (Ratledge and Brown 1972; Brown and Ratledge 1975). Iron dependent enzymes, such as glycerol dehydrogenase and NADH-cytochrome c reductase, showed reduced activity as well. Finally, PAS affects the biosynthesis of mycobactin S. These data suggest that a primary mode of action of this drug is a disruption of the iron acquisition and utilization. Since PAS may partially exert its inhibitory action through a disruption in mycobactin biosynthesis, further exploration of agents designed to inhibit the biosynthesis of the mycobacterial siderophores may be a viable route for the development of anti-infectious drugs. The use of modified intermediates in the biosynthetic pathway or development of novel inhibitors of the biosynthetic enzymes may reduce the amount of the siderophores present for iron acquisition. Recent elegant independent studies by Aldrich (Somu et al. 2006) and Quadri (Ferreras et al. 2005; Quadri 2007) have shown that designed inhibitors of early steps of siderophore (mycobactin) biosyntheses by M. tuberculosis are potent anti-TB agents, again reflecting the absolute dependence on iron acquisition for growth and virulence of TB.

Detailed studies and the structural elucidation of the mycobactins in the 1960s led Snow to hypothesize and demonstrate that antagonists to the growth of one species of mycobacteria may be found in the naturally occurring mycobactins of another (Snow 1970). Depressed growth rates of M. paratuberculosis, M. kansasii and M. tuberculosis were found when cultures were inoculated with either mycobactins M or N. Furthermore, treatment of M. paratuberculosis with combinations of mycobactins P and either M or N led to growth rates significantly slower than treatment of the microbes with any of them individually. Another study on the growth inhibition by natural mycobactins revealed the growth inhibition of M. aurum by ferrimycobactins J and S (Bosne-David et al. 1997). We have verified Snow’s hypothesis by synthesizing and studying mycobactin analogs that posses potent antituberculosis activity.

As with many natural products, especially peptide-based compounds, synthesis of the mycobactins and anlogs required preparation of the components (A–F, Fig. 5) and subsequent assembly either in a linear fashion or by segment condensation. A generalized structure of mycobactins, analogs and their components is shown in Fig. 5. Most often, the two main constituents, mycobactic acids and cobactins, are synthesized and then coupled to give the complete mycobactin core. Mycobactins consist of a phenolic oxazoline derived from hydroxybenzoic acid and serine or threonine and a lysine-based hydroxamate, whereas the cobactins are composed of cyclic lysine hydroxamates that are N-acylated with a beta-hydroxy carboxylic acid. We and others have synthesized each of the individual component fragments (A–D) and assembled them to give complete mycobactins, analogs and truncated versions for anti-TB screening (Walz and Miller 2007; Somu Somu et al. 2006) (Fig. 6).

The power of syntheses to prepare mycobactins directly related to those in nature and unnatural analogs is also demonstrated by the few examples shown in Fig. 5. For instance, synthesis and study of a form (C16 acyl group) of mycobactin T confirmed that it was a growth promoter for tuberculosis; however, we found that change of a single diastereomeric center of the beta-hydroxy butyrate component to generate the corresponding mycobactin S, produced a potent TB growth inhibitor, thus, further illustrating Snow’s hypothesis! With the intent of eventually preparing mycobactin-like siderophore-drug conjugates, we synthesized YPX-I-145 in which we substituted a beta-amino acid, diaminopropionate, for the usual beta-hydroxy carboxylic acid component. Through broad screening of our compounds we found that YPX-I-145 was a potent anti-TB agent (0.2 μg/ml)! Interestingly, the corresponding free amine generated by removal of the Boc “protecting group” was completely inactive, presumably because the resulting free amine is protonated under physiological conditions and is not compatible with the hydrophobic environment normally associated with natural mycobactins. As with the difference in activity between mycobactin T and S, we also found that while YPX-I-145 with the “S” configuration of the diaminopropionate had impressive anti-TB activity while the “R” analog was completely inactive! (Fig. 7).

Subsequent to these early syntheses and generation of significant anti-TB activity our goal was to develop scalable syntheses of mycobactins and, especially, the lead analog YPX-I-145. This has been accomplished and is summarized below. Note that the assembly was accomplished in up to 50% overall yield!.

Using similar methodology, many full mycobactin analogs were synthesized for our studies. In addition to optimizing the synthesis of YPX-I-145, we repeated the syntheses of mycobactins T (TB growth promoter), S (TB growth inhibitor), S2 [analog with short acyl (acetyl) side chain, not active], and other YPX analogs [pivaloyl (NOT active, though structurally only one oxygen different than YPX-1-145!)], Cbz (only slightly active), free amine (not active, is positively charged at physiological pH), retrohydroxamate, small side chain amides and esters (presumably not hydrophobic enough)] to more fully elaborate SAR. The latter compounds indicate the need for a complete hexadentate iron (III) binding core.

The lack of activity of the analogs missing at least one iron binding component indicates the apparent need for a complete hexadentate iron (III) binding core. The synthesis of an analog missing the iron binding groups was reported in 1969 (Carpenter and Moore 1969). No activity was reported. We synthesized the corresponding dideoxy mycobactin T (no hydroxamates, i.e., N–OH groups replaced with NH) and several analogs and found that they had no anti-TB activity. Coincidently, Dr. Branch Moody, Children’s Hospital at Harvard, had obtained preliminary evidence that dideoxy mycobactins were biosynthesized by mycobacteria, including TB, and the implication was that they might be biosynthetic precursors of hydroxamate containing mycobactins. While this would be consistent with recent reports from the Walsh group (Quadri et al. 1998), it would represent a departure from the usual biosyntheses of siderophore hydroxamates that reportedly occur by amine oxidation followed by acylation. Still more interesting was the preliminary finding that these lipopeptide dideoxymycobactins stimulated T cells. We established a collaboration with Dr. Moody and confirmed this unique character of the dideoxy mycobactins (Moody et al. 2004). A subsequent detailed rationale for the interaction of dideoxymycobactins based on an x-ray structure determination of one of our synthetic analogs bound to CD1 has been published (Zajonc et al. 2005). Thus, while again reaffirming the obvious need for iron binding groups for mycobactins to be effective mycobacterial growth promoters or inhibitors, “offshoots” of our synthetic work have had additional value (Fig. 8).

Besides preparing and testing all of the individual components, protected versions and analogs, we combined them into “truncated” mycobactins that contain some, but not all of the normal components of mycobactins and active analogs. Representative examples of the many prepared are shown above. None of the truncated analogs had significant activity.

Early in this synthetic program, we also submitted representative synthetic intermediates of mycobactin components for testing and obtained significant, unexpected hits that produced new lead anti-TB structures! Thus, the simple protected, non-iron binding oxazoline JH-II-122, was found to have notable anti-TB activity (Fig. 5), though the corresponding deprotected phenol and acid derivatives had no activity. Detailed extensive structure-activity-relationship (SAR) studies have been performed around this small molecule anti-TB lead compound and will be reported separately.

Since we found significant anti-TB activity with the oxazoline analogs and derivatives, we also submitted hundreds of samples of the linear and cyclic forms of the lysine components and the beta-hydroxy acids, esters and amides, and, as indicated earlier, entire mycobactic acid fragments, cobactin fragments, truncated analogs of mycobactins, related esters and amides in protected and unprotected forms and found none to have significant activity against TB or other forms of mycobacteria and a broad set of Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. For example, all zone “C”, “D”, “E” and “F” components and protected forms were inactive against TB at 32 μM and all zone “C” + “D” + “E” + “F” combinations were inactive at 32 μM. These combined SAR studies indicate that, besides finding that hydrophobic forms of the oxazolines corresponding to zones “A” + “B”, full mycobactin structures are needed for growth promotion or inhibition. Thus, future studies will focus on elaboration of the SAR of the oxazoline lead and design, syntheses and studies of mycobactin-drug conjugates to test the “Trojan Horse” concept for development of new anti-TB agents.

Additional therapeutic potential of mycobactins: siderophores as potential anti cancer agents

Other possible therapeutic applications of mycobactins and related compounds are summarized here to emphasize the overall potential of mycobactins. A number of mycobactin-like compounds have been isolated and determined to have interesting biological activity. Interestingly, these natural analogs have not been tested for anti-TB activity, but would help determine further SAR parameters (Fig. 9).

Inhibition of oxidative damage in mammals

Hydrogen peroxide and superoxide radicals can initiate Fenton reactions that is in the generation of damaging hydroxyl radicals (Walling 1975) in vivo, and are catalytic in iron(II) (Zweier 1988; Graf et al. 1984; Floyd and Lewis 1983). This chemistry can cause reperfusion injury to ischemic organs. Desferrioxamine (Gutteridge et al. 1979) and some of our previous synthetic siderophore analogs, spermetaxins and spermetaxols (Miller and Malouin 1994), are able to inhibit this type of oxidative damage. Carboxymycobactins from M. tuberculosis were found to be cardiac reperfusion injury inhibitors (Horwitz et al. 1988, 1999). Desferricarboxymycobactins were markedly more active than desferroxamine, in their ability to preserve systolic and diastolic left ventricular function and blood flow after a period of ischemia in isolated rabbit hearts. Chelation of ferric iron by carboxymycobactins in the cardiac cellular lipid compartments may be the basis for the activity in that lipid oxidation is thought to be a cause of reperfusion injury (Kong et al. 1994). The use of desferricarboxymycobactins for the treatment of atherosclerosis and vascular injury by prevention of smooth muscle proliferation has been patented (Horwitz 1998).

The mycobactins were originally thought to be exclusively produced by mycobacteria. However, recently mycobactin-like structures have been isolated from other microbes, including Rhodococcus (Hall and Ratledge 1986) and Nocardia (Ratledge and Patel 1976; Ratledge and Snow 1974; Patel and Ratledge 1973). Formobactin, from Nocardia sp. strain ND20, exhibited an IC50 of 0.65 μM against lipid peroxidation in rat brain homogenate (Murakami et al. 1996). It also reduced l (l)-glutamate toxicity in neuronal cells (EC50 0.017 μM) and suppressed apoptotic cell death by the oxygen radical producer buthione sulfoximine (EC50 0.072 μM). These studies suggest that the mycobactins, carboxymycobactins, and analogs may possess potent anti-oxidative activity due to their lipid solubility and ability to chelate iron(III). Nocardimicins A–F, have been isolated from Nocardia sp. TP-A0674 and reported to have potent muscarinic M3 receptor inhibiting activity, but no indication was given regarding microbial growth promotion or inhibition (Ikeda et al. 2005) (Fig. 10).

Anticancer agents

BE-32030 A–E isolated from Nocardia sp. A32030 (Tsukamoto et al. 1997) and the amamistatins A and B from an actinomycete (Suenaga et al. 1999) have anticancer activity. Growth of T47D-YB human breast cancer cells was inihibited by the carboxymycobactins of M. tuberculosis (Horwitz et al. 1999). Screening the compounds above against TB to further elaborate the SAR of “Snow’s Hypothesis” would be of interest, but no reports have appeared regarding activities of these compounds as either TB growth promoters or inhibitors.

We recently reported the syntheses of amamistatin B, a diastereomer and an analog lacking iron binding hydroxamates. Although the structurally similar, but more hydrophobic mycobactin M reportedly has anti-TB activity, we found that amamistatin B, its diastereomer and non-iron binding analog had low anti-TB activity, and that amamistatin B and its diastereomer promoted the growth of several strains of mycobacteria and other Gram positive bacteria. Consistent with the earlier reports that natural amamistatins have potent anticancer activity, we found that synthetic amamistatin B and its diastereomer were active against both breast and prostate cancer cell lines (Fennell et al. 2008).

Conclusion

Siderophores have tremendous therapeutic potential that is barely tapped. The critical need by all microbes to assimilate iron can be utilized to develop new microbe-selective antibiotics either by limiting microbial iron uptake by competitive iron chelation, inhibiting siderophore biosynthesis or developing “Trojan Horse” antibiotics based on siderophore-drug conjugates. New applications of siderophores in chemotherapy are also being realized.

References

Barclay R, Ratledge C (1983) Iron-binding compounds of Mycobacterium avium, M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, and mycobactin-dependent M. paratuberculosis and M. avium. J Bacteriol 53:1138–1146

Benz G (1984) Albomycine, I. Enzymatische Spaltung der Desferriform der Albomycine. Liebigs Ann Chem 1399–1407. doi:10.1002/jlac.198419840802

Benz G, Schmidt D (1984) Albomycins, 4. Isolation and total synthesis of (N-5-acetyl-N-5-hydroxy-L-Ornithyl). Liebigs Ann Chem 1434–1440. doi:10.1002/jlac.198419840805

Benz G, Schroder T, Kurz J, Wunsche C, Karl W, Steffens G, Pfitzner J, Schmidt D (1982) Konstitution der Desferriform der Albomycine. Angew Chem Suppl 1322–1335

Benz G, Born L, Briedan M, Grosser R, Kurz J, Paulsen H, Sinnwell V, Weber B (1984) Albomycins, II. Absolute Konfiguration der Desferriform der Albomycine. Liebigs Ann Chem 1408–1423. doi:10.1002/jlac.198419840803

Bosne-David S, Bricard L, Ramiandrasoa FDéRoussent A, Kunesh G, Andremont A (1997) Evaluation of growth promotion and inhibition from Mycobactins and nonmycobacterial Siderophores (Desferrioxamine and FR160) in Mycobacterium aurum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1837–1839

Braun V, Endriß F (2007) Energy-coupled outer membrane transport proteins and regulatory proteins. Biometals 20:219–231. doi:10.1007/s10534-006-9072-5

Braun V, Günthner K, Hantke K, Zimmermann L (1983) Intracellular activation of albomycin in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 156:308–315

Brochu A, Brochu N, Nicas TI, Parr TR, Minnick AA, Dolence EK, McKee JA, Miller MJ, Lavoie MC, Malouin F (1992) Modes of action and inhibitory activities of new siderophore-b-lactam conjugates that use specific iron uptake pathways for entry into bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36:2166–2175

Brown KA, Ratledge C (1975) The effect of p-aminosalicylate on iron transport and assimilation in Mycobacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta 385:207–220

Budzikiewicz H (2004) Siderophores of the Pseudomonadaceae sensu stricto (fluorescent and non-Fluorescent Psedomonas spp.). Prog Chem Org Nat Prod 87:81–327

Bullen JJ (1987) In: Bullen DJ, Griffiths E (eds) Iron and infection: molecular, physiological and clinical aspects, Wiley, New York, pp 1–526

Carpenter JGD, Moore JW (1969) Synthesis of an analogue of mycobactin. J Chem Soc 1610–1611

Dhungana S, Miller MJ, Dong L, Ratledge C, Crumbliss AL (2003) Fe(III) chelation properties of an extracellular siderophore exochelin MN. J Am Chem Soc 125:7654–7663. doi:10.1021/ja029578u

Dolence EK, Minnick AA, Miller MJ (1990) N5-acetyl-N5-hydroxy-l-ornithine-derived siderophore-Carbacephlosporin β-Lactam conjugates: iron transport mediated drug delivery. J Med Chem 33:461–464. doi:10.1021/jm00164a001

Dolence EK, Lin C-E, Miller MJ (1991a) Synthesis and siderophore activi ty of albomycin-like peptides derived from N5-acetyl-N5-hydroxy-l-orinithine. J Med Chem 34:956–968. doi:10.1021/jm00107a013

Dolence EK, Minnick AA, Lin C-E, Miller MJ (1991b) Synthesis and siderophore and antibacterial activity of N5-acetyl-N5-hydroxy-l-ornithine-derived Siderophore-β-lactam conjugates: iron-transport-mediated drug delivery. J Med Chem 34:968–978. doi:10.1021/jm00107a014

Dong L, Roosenberg JM, Miller MJ (2002) The total synthesis of deferrisalmycin B. J Am Chem Soc 124:15001–15005. doi:10.1021/ja028386w

Fennell KA, Möllmann U, Miller MJ (2008) Syntheses and biological activity of amamistatin B and analogs. J Org Chem 73:1018–1024. doi:10.1021/jo7020532

Ferguson AD, Hofmann E, Coulton JW (1998) Siderophore-mediated Iron tansport: crystal structure of FhuA with bound lipopolysaccharide. Science 282:2215. doi:10.1126/science.282.5397.2215

Ferguson AD, Chakraborty R, Smith BS, Esser L, van der Helm D, Deisenhofer J (2002) Structural basis of gating by the outer membrane transporter FecA. Science 295:1715–1719. doi:10.1126/science.1067313

Ferreras JA, Ryu JS, Di Lello F, Tan DS, Quadri LEN (2005) Small molecule inhibition of siderophore biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Yersinia pestis. Nat Chem Biol 1:219–232. doi:10.1038/nchembio706

Floyd RA, Lewis CA (1983) Hydroxyl free-radical formation from hydrogen peroxide by ferrous iron nucleotide complexes. Biochemistry 22:2645–2649. doi:10.1021/bi00280a008

Ghosh A, Ghosh M, Niu C, Malouin F, Möllmann U, Miller MJ (1996) Iron transport-mediated drug delivery using mixed-ligand siderophore-β-lactam conjugates. Chem Biol 3:1011–1019. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(96)90167-2

Graf E, Mahoney JR, Bryant RG, Eaton JW (1984) Iron-catalysed hydroxyl radical formation-stringent requirement for free iron coordination site. J Biol Chem 259:3620–3624

Guerinot ML (1994) Microbial iron transport. Annu Rev Microbiol 48:743. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003523

Gutteridge JMC, Richmond R, Halliwell B (1979) Inhibition of iron-catalyzed formation of hydroxyl radicals for superoxide and lipid peroxidation by desferrioxamine. Biochem J 184:469–472

Hall RM, Ratledge C (1986) Distribution and application of mycobactins for the characterization of species within the genus Rhodococcus. J Gen Microbiol 132:853–856

Heinisch L, Wittmann S, Stoiber T, Berg A, Ankel-Fuchs D, Möllmann U (2002). J Med Chem 45:3032–3040. doi:10.1021/jm010546b

Hider RC (1984) Structure and bonding, vol 58. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, p 25

Horwitz LD (1998) Method of treatment of atherosclerosis and vascular injury by the prevention of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. US Patent 5786326 and Chem Abstr 129:144856p

Horwitz LD, Sherman NA, Kong Y, Pike AW, Gobin J, Fennessey PV, Horwitz MA (1988) Lipophilic siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis prevent cardiac reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:5263–5268. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.9.5263

Horwitz LD, Horwitz MA, Gibson BW, Reeve J (1999) Use of exochelins in the preservation of organs for transplant. US Patent 5721209 and Chem Abst 130:47472y

Ikeda Y, Nonaka H, Furrmai T, Onaka H, Igarashi Y (2005) Nocardimicins A, B, C, D, E and F, siderophores with Muscarinic M3 reeptor Inhibiting activity from Nocardia sp. TP-A0674. J Nat Prod 68:1061–1065

Jaynes BH, Dirlam JP, Hecker SJ (1996) Antibacterial agents. In: Bristol JA (ed) Annual reports in medicinal chemistry, vol 31. Academic Press, London, pp 121–130

Katsu K, Kitoh K, Inoue M, Mitsuhashi S (1982) In vitro antibacterial activity of E-0702, a new semisynthetic cephalosporin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 22:181–185

Kong Y, Lesneefsky EJ, Ye J, Horwitz LD (1994) Prevention of lipid peroxidation does not prevent oxidant-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. Am J Physiol 267:H2371–H2377

Levy SB (1992) The antibiotic paradox how miracle drugs are destroying the miraclej. Plenum Press, New York, pp 1–296

Macham LP, Ratledge C (1975) A new group of waster-soluble iron-binding compounds from Mycobacteria: the exochelins. J Gen Microbiol 89:379–382

Macham LP, Ratledge C, Nocton JC (1975) Extracellular iron acquisition by Mycobacteria: role of the exochelins and evidence against the participation of mycobactin. Infect Immun 12:1242–1251

Macham LP, Stephenson MC, Ratledge C (1977) Iron transport in Mycobacterium smegmatis: the isolation, purification and function of exochelin MS. J Gen Microbiol 101:41–49

McCready KA, Ratledge C (1977) Mycobactins from Mycobacterium avium. Int J Syst Bacteriol 7:288–289

Mckee JA, Sharma SK, Miller MJ (1991) Iron transport mediated drug delivery systems: synthesis and antibacterial activity of spermidine- and lysine-based siderophore-β-lactam conjugates. Bioconjug Chem 2:281–291

Messenger AJM, Hall RM, Ratledge C (1986) Iron uptake processes in Mycobacterium vaccae R877R, a Mycobacterium lacking mycobactin. J Gen Microbiol 132:845–852

Miethke M, Marahiel MA (2007) Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:413–415

Miller MJ (1989) Syntheses and therapeutic potential of hydroxamic acid based siderophores and analogues. Chem Rev 89:1563–1579

Miller MJ, Malouin F (1993) Microbial iron chelators as drug delivery agents: rational design and synthesis of siderophore-drug conjugates. Acc Chem Res 26:241–249

Miller MJ, Malouin F (1994) Sjiderophore-mediated drug delivery: the design, synthesis, and study of siderophore-antibiotic and antifungal conjugates. In: Bergeron RJ, Brittenham GM (eds) The development of iron chelators for clinical use. CRC, Boca Ratonj, pp 275–306

Miller MJ, Malouin F, Dolence EK, Gasparski CM, Ghosh M, Guzzo PR, Lotz BT, McKee JA, Minnick A, Teng M (1993) Iron transport mediated drug delivery. In: Bently PH, Ponsford R (eds) Recent advances in the chemistry of anti-infective agents, vol 119. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, pp 135–159

Minnick AA, McKee JA, Dolence EK, Miller MJ (1992) Iron transport-mediated antibacterial activity of and development of resistance to hydroxamate and catechol siderophore-carbacephalosporin conjugates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36:840–850

Moody DB, Yung DC, Cheng T-Y, Rosat J-P, Roura-mir C, O’Connor PB, Zajonc DM, Walz A, Miller MJ, Levery SB, Wilson IA, Costello CE, Brenner MB (2004) T cell activation by lipopeptide antigens. Science 303:527–531

Morrison NE (1995) Mycobacterium leprae iron nutrition: bacterrioferritin, mycobactin, Exochelin and inatracellular growth. Int J Lepr 63:86–91

Murakami Y, Kato S, Nakajima M, Matsuoka M, Kawai H, Shin-Ya K, Seto H (1996) Formobactin, a novel free radical scavenging and neuronal cell protecting substance from Nocardia sp. J Antibiot 49:839–845

Neilands JB, Valenta JR (1985) Iron-containing antibiotics. In: Sigel H (ed) Metal ions in biological systems, vol 19. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 313–333

Patel PV, Ratledge C (1973) Isolation of lipid-soluble compounds that bind ferric ions from Nocardia species. Biochem Soc Trans 1:886–888

Paulsen H, Briedan M, Benz G (1987) Branched and chain-extended sugars. synthesis of the deferri form of the oxygen analog of delta-1-albomycin. Liebigs Ann Chem 8:565–575

Payne SM (1988) Iron and virulence in the family Enterobacteriacae. CRC Crit Rev Microbiol 16:81

Quadri LEN (2007) Strategic paradigm shifts in the antimicrobial drug discovery process of the 21st century. Infectious disorders—drug targets 7:230–237

Quadri LEN, Sello J, Keating TA, Weinreb PH, Walsh CT (1998) Identification of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene cluster encoding the biosynthetic enzymes for assembly of the virulence-conferring siderophore mycobactin. Chem Biol 5:631–645

Ratledge C (1971) Transport of iron by mycobactin in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 45:856–862

Ratledge C (1984) Metabolism of iron and other metals by Mycobacteria. Microbiol Ser 15:603–627

Ratledge C (1987) In: Winkelmann G, van der Helm D, Neilands JB (eds) Iron transport in microbes, plants, and animals. VCH Press, Weinheim, FRG, pp 207

Ratledge C (2004) Iron, mycobacteria and tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 84:110–130

Ratledge C, Brown KA (1972) Inhibition of mycobactin formation in Mycobacterium smegmatis by p-aminosalicylate. Am Rev Resp Dis 106:774–776

Ratledge C, Marshall BJ (1972) Iron transport in Mycobacterum smegmatis: the role of mycobactin. Biochim Biophys Acta 279:58–74

Ratledge C, Patel PV (1976) The isolation, properties and taxonomic relevance of lipid-soluble, iron-binding compounds (the nocobactins) from Nocardia. J Gen Microbiol 93:141–152

Ratledge C, Snow GA (1974) Isolation and structure of nocobactin na, a lipid-soluble iron-binding compound from Nocardia asteroids. Biochem J 139:407–413

Ratledge C, Patel PV, Mundy J (1982) Iron transport in Mycobacterium smegmatis: the location of mycobactin by electron microscopy. J Gen Microbiol 128:1559–1565

Rogers HJ (1987) Bacterial iron transport as a target for antibacterial agents. In: Winkelmann G, van der Helm D, Neilands JB (eds) Iron transport in microbes, plants, and animals. VCH Press, Weinheim, pp 223–233

Roosenberg JM, Lin Y-M, Lu Y, Miller MJ (2000) Studies and syntheses of siderophore, microbial iron chelators, and analogs as potential drug delivery agents. Curr Med Chem 7(2):159–197

Sharman GJ, Williams DH, Ewing DF, Ratledge C (1995a) Isolation, purification and structure of exochelin MS, the extracellular siderophore from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biochem J 305:187–196

Sharman GJ, Williams DH, Ewing DF, Ratledge C (1995b) Determination of the structure of exochelin MN, the extracellular Siderophore from Mycobacterium neoaurum. Chem & Biol 2:553–561

Snow GA (1970) Mycobactins: iron-chelating growth factors from Mycobacteria. Bacteriol Rev 34:99–125

Somu RV, Wilson DJ, Bennett EM, Boshoff H, Celia L, Beck BJ, Barry CEIII, Aldrich CC (2006) Antitubercular nucleosides that inhibit siderophore biosynthesis: SAR of the glycosyl domain. J Med Chem 49:7623–7635

Stephenson MC, Ratledge C (1978) The transport of iron from ferriexochelin by Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biochem Soc Trans 6:423–425

Stephenson MC, Ratledge C (1979) Iron transport in Mycobacterium smegmatis: uptake of iron from ferriexochelin. J Gen Microbiol 110:193–202

Suenaga K, Kokubo S, Shinohara C, Tsuji T, Uemura D (1999) Structures of Amamistatins A and B, novel growth inhibitors of human tumor cell lines from an Actinomycete. Tetrahedron Lett 40:1945–1948

Tsukamoto M, Murooka K, Nakajima S, Abe S, Suzuki H, Hirano K, Kondo H, Kojira K, Suda H (1997) BE-32030 A, B, C, D, and E, new antitumor substances produced by Nocardia sp. A32030. J Antibiot 50:815–821

Vergne AF, Walz AJ, Miller MJ (2000) Iron chelators from Mycobacteria (1954–1999) and potential therapeutic applications. Nat Prod Rep 17:99–116

Vertesy W, Aretz W, Fehlhaber H-W, Kogler H (1995) Salmycin A-D, Antibiotika aus Streptomyces violaceus, DSM 8286, mit Siderophore-Aminoglycosid-Struktur. Helv Chim Acta 78:46–60

Walling C (1975) Fenton’s reagent revisited. Acc Chem Res 8:125–131

Walz AJ, Miller MJ (2007) β-Lactams in synthesis: short syntheses of cobactin analogs. Tetrahedron Lett 48:5103–5105

Watanabe N-A, Nagasu T, Katsu K, Kitoh K (1987) E-0702, a new cephalosporin, is incorporated into Escherichia coli cells via the tonB-dependent iron transport system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 31:497–504

Wheeler PR, Ratledge C (1994) Metabolism of M. tuberculosis. In: Bloom BR (ed) Tuberculosis pathogenesis, protection, and control. American Society of Microbiology, Washington, pp 353–385

Winkelmann G, van der Helm D, Neilands JB (1987) (eds) Iron transport in microbes, plants, and animals. VCH Press, Weinheim, FRG, pp 1–533

Zajonc DM, Crispin MDM, Bowden TA, Young DC, Cheng T-Y, Hu J, Costello CE, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Miller MJ, Brenner MB, Moody DB, Wilson IA (2005) Molecular mechanism of lipopeptide presentation by CD1a. Immunity 22:209–219

Zweier JL (1988) Measurement of superoxide-derived free-radicals in the reperfused heart-evidence for a free-radical mechanism of reperfusion injury. Biol Chem 263:1353–1357

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIH (AI054193) and the US Army Medical Research & Material Command (DAMD17-03-1-0206). The authors gratefully acknowledge Mrs. Patty Miller for performing MCF-7 and PC-3 cellular assays at Notre Dame. Baojie Wan at the University of Chicago’s Institute for Tuberculosis Research kindly provided M. tuberculosis inhibition data. The excellent technical assistance of Irmgard Heinemann and Uta Wohfield with microbial assays at the HKI is greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, M.J., Zhu, H., Xu, Y. et al. Utilization of microbial iron assimilation processes for the development of new antibiotics and inspiration for the design of new anticancer agents. Biometals 22, 61–75 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-008-9185-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-008-9185-0