Abstract

Microcosms were set up with a PAHs-contaminated soil using biostimulation (addition of ground corn cob) and bioaugmentation (inoculated with Monilinia sp. W5-2). Degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and microbial community were examined at the end of incubation period. After 30 days, bioaugmented microcosms showed a 35 ± 0% decrease in total PAHs, while biostimulated and control microcosms showed 16 ± 9% and 3 ± 0% decrease in total PAHs, respectively. Bioaugmented microcosms also revealed 70 ± 8% and 72 ± 2% decreases in benzo[a]pyrene and anthracene, respectively, while the values for biostimulated and control microcosms were much lower. Detoxification of soils in bioaugmented microcosms was confirmed by genetic toxicity assay, suggesting important role of fungal remediation. Molecular fingerprint profiles and selective enumeration showed biostimulation with ground corn cob increased both number and abundance of indigenous aromatic hydrocarbons degraders and changed microbial community composition in soil, which is beneficial to natural attenuation of PAHs. At the same time, bioaugmentation with Monilinia strain W5-2 imposed negligible effect on indigenous microbial community. This study suggests that fungal remediation is promising in eliminating PAHs, especially the part of recalcitrant and highly toxic benzo[a]pyrene, in contaminated soil. It is also the first description of soil bioremediation with Monilinia sp.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are a class of toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic chemicals that are ubiquitous in environment. The high-molecular-weight (HMW) PAHs are more hydrophobic and recalcitrant, so less degradable to microorganisms than the low-molecular-weight (LMW) PAHs. Although the LMW PAHs-degrading bacteria are widely spread in soil (Juhasz and Naidu 2000), less bacteria metabolize HMW PAHs, especially the highly toxic benzo[a]pyrene.

Fungal remediation, or mycoremediation, which means fungal treatment or fungal-based remediation, is a promising technique for cleanup of contaminated soil. The PAHs-transforming capability of fungi mainly comes from their extracellular ligninolytic enzymes, i.e. lignin peroxidase (LiP), manganese peroxidase (MnP) and laccase. In addition, some fungi degrade PAHs via mechanism similar with mammals (using intracellular cytochrome P450 enzymes) (Barnforth and Singleton 2005; Cerniglia 1997). White rot fungi (WRF) are among the most extensively studied species for they are capable of degrading a wide range of xenobiotic compounds, including PAHs (Bogan et al. 1999; Collins et al. 1996; Pickard et al. 1999). However, the colonization potential of WRF in soil is reported to be limited (Andersson et al. 2001; McErlean et al. 2006), and the depletion of PAHs by WRF may be hindered by limiting environmental factors (Tortella and Diez 2005). It is reported that some litter-decomposing fungi can colonize soil and degrade PAHs (Steffen et al. 2002), and indigenous non-ligninolytic fungi isolated from soil transform PAHs significantly (D’Annibale et al. 2006; Potin et al. 2004), suggesting that known PAHs-degrading fungi are relatively less compared to the highly diverse fungi kingdom and there is a huge fungi pool in terrestrial ecosystem from which potent PAHs degrading strains remain to be explored. So effort should be put into isolation and identification of PAHs-removing and environmentally adaptive fungi from terrestrial ecosystem.

In addition, the impact of remedial treatment on indigenous microorganism community cannot simply be ignored. Fungi usually do not mediate complete mineralization of pollutants, so sequential fungal-bacterial degradation is necessary for soil detoxification. In soil, bacterial-fungal and interfungal interaction is widespread (Thorn 1997). It has been suggested that fungal inoculation reduce the number of indigenous bacteria along with depletion of pollutants (Andersson et al. 2003) or change the soil bacterial community (Corgie et al. 2006). So microbial effect of fungi used in remediation should be investigated before field utility.

In the present study, soil microcosms were set up with different treatments (biostimulation with nutrient and bioaugmentation with fungal inoculum) to test the potential of fungal remediation on an aged PAHs-contaminated soil, which was not compatible with agricultural/residential/parkland uses according to Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines due to the high PAHs contents. At the end of incubation, PAHs and indigenous aromatic hydrocarbons degraders (AHD) were determined, and microbial community compositions were analyzed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). Results indicate the fungus tested has high potential in removing PAHs, especially the highly toxic benzo[a]pyrene, without apparently negative effect on indigenous microorganisms.

Materials and methods

Soil

Bulk soil used in this microcosm study was collected from a liquefied petroleum gas station located in Wuxi, Jiangsu, China. The soil pH was 6.4, organic matter 19.2 g kg−1, total nitrogen 1.0 g kg−1, total phosphorus 0.5 g kg−1, total potassium 14.2 g kg−1, CEC 21.5 cmol kg−1, and concentration of 15 individual PAHs are described in Table 1. Before used, the soil was air-dried, passed through a 2 mm sieve, and stored at 4°C in darkness.

Fungus and inoculum preparation

Fungus strain W5-2 was isolated previously from a historically PAHs-contaminated soil collected from Wuxi, Jiangsu, China based on a laccase activity assay (Coll et al. 1993). The morphological characteristics of strain W5-2 including its spores were compared with those of the known species of fungi (Wei 1979) and it was strongly suggested that strain W5-2 belongs to the genus Monilinia. The fungus was maintained on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plates at 4°C.

For bioaugmentation, 7-day-old mycelium in liquid media was homogenized and 1 ml suspensions were inoculated into 250 ml flasks containing 49 ml media. After incubation in dark at 180 rpm and 28°C for 7 days, the precultures were centrifuged and washed with dH2O. The mycelium was homogenized with dH2O to yield a biomass concentration of approximately 3 g l−1. For bioaugmentation, 50 ml suspension was inoculated.

The liquid media included (g l−1): glucose 20, KH2PO4 2, MgSO4 · 7H2O 0.5, CaCl2 0.1, yeast extract 0.2.

Microcosms

Microcosms were run in triplicates, containing 1 kg non-sterile soil (dry weight). For bioaugmented microcosms, soils were inoculated with 50 ml mycelium suspensions of Monilinia sp. W5-2 pre-mixed with 50 g ground corn cob. The water holding capacity (WHC) of microcosms was adjusted to 60%. Biostimulated microcosms were set up with the same treatment as described above except addition of fungus culture. Control microcosms were run at the same time with no addition of inoculum and nutrient. All microcosms were incubated at room temperature for 30 days in darkness.

PAHs extraction and HPLC

Five grams frozen dried soil samples (in triplicates) were extracted with 60 ml dichloromethane in a Soxhlet apparatus for 24 h. Extracts were concentrated using a rotary evaporator and purified with column chromatography filled with activated silica gel before analysis by HPLC.

Determination of 15 out of 16 EPA PAHs (except acenaphthene) was carried out according to the method of Ping et al (2007). Briefly, analysis was conducted on a Shimadzu Class-VP HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan), with a fluorescence detector (RF-10AXL). A reversed phase column C18 (VP-ODS 150 × 4.6 mm I. D., particle size 5 μm), using a mobile phase of water and acetonitrile mixture (1:9, v/v) at a constant solvent flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1, was used to separate 15 PAHs. The excitation and emission wavelengths for individual PAH were set separately.

The percentage of PAHs loss (%D) was given by the formula: %D = 100[(MI − MT)/MI], where MT was the concentration of PAHs in each treatment and MI was the initial PAHs concentration present in soil. The mean (m) and the standard deviation (SD) were calculated and are shown in Table 1.

Genotoxic assay

Soil was extracted as described previously (Plaza et al. 2005). Briefly, 5 g soil (in triplicates) was extracted by dichloromethane for 24 h. Once the extract volume was reduced to approximately 5 ml by rotary evaporating, 1.5 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added and the final volume should be 1.5 ml under reduced pressure. The umu test (without S9 addition) with Salmonella typhimurium NM2009 was performed on microplates following International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard (ISO 2000). By definition, the genotoxicity of sample is the lowest reciprocal dilution factor that is not genotoxic.

Enumeration of AHD

AHD were counted at the end of incubation using a miniaturized most probable number (MPN) method in 96-well microplates with five replicates per dilution (Wrenn and Venosa 1996). Briefly, phenanthrene, anthracene, fluorene, and dibenzothiophene were added as the sole carbon sources to support the proliferation of aromatics-degrading bacteria. Serially diluted samples were inoculated into the wells and the microplates were incubated at room temperature for 3 weeks. The wells turned yellow or brown owing to the accumulation of partial oxidation products of aromatic substrates were treated as positive. Published MPN tables were used to decide the MPN.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Soil DNA was extracted from 0.5 g soil using the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (Q-BIOgen, Irvine, CA) according to user’s manual. A 230-bp fragment, of which 180-bp is from the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria, was amplified by using GC-clamp primers described previously (Muyzer et al. 1993) on a PTC-100 thermalcycler (MJ Research, Inc., Watertown, MS). Each 50 μl PCR mixture contained 1 × PCR buffer, 200 μM nucleotide mixture, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM (each) primer, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Shanghai, China), and 1 μl DNA extract was added. The PCR procedure consisted of a touchdown reaction and additional 10 cycles described previous (Dilly et al. 2004). For eukaryotic population, primer pair 403f/662r-gc was used to amplify partial sequences of eukaryotic 28S rRNA gene. PCR was conducted following Sigler and Turco (2002).

DGGE

DGGE was performed on a DCode Universal Mutation Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). PCR products were all separated in an 8% acrylamide gels with a denaturing gradient from 30 to 60% (100% denaturant corresponds to 7 M urea and 40% formamide). Gels were running in 1 × TAE buffer at 60°C and 75 V for 800 min, and stained for 30 min in 1 × TAE containing SYBR Green I (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), documented by Gel Doc™ EQ gel documentation system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Analysis of DGGE profiles

DGGE image was digitalized and processed by Gelcompar II package (Applied Maths, Inc., Austin, TX) with default values. After normalization, bands with relative peak area intensities were included in further analysis. Shannon-Wiener diversity index of microbial community was calculated as \( H'\; = \; - {\sum\limits_{i = 1}^S {P_i\; \times \;\ln P_i} } \) where P i is the percentage of the total intensity accounted for by the ith band. Cluster analysis of bacterial profiles was performed using Gelcompar II to construct a dendrogram using unweighted pair group method (UPGMA) based on Pearson’s similarity coefficient calculated from the complete densitometric curves.

Sequence analysis

Concise DGGE bands were excised and reamplified as described (Wilms et al. 2006). For purification, a second DGGE was run and bands with identical position to parent bands were excised, amplified again with primer pairs without GC clamp. Sequencing of PCR products were carried out by Invitrogen (Shanghai, China). DNA sequences were compared to those in the GenBank (Altschul et al. 1997). Due to a limitation of eukaryotic ribosomal sequences database, we did not perform the sequencing of DGGE bands in eukaryotic profile.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test was performed using SPSS package (version 11.5; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) on the primary data in each case to evaluate the statistical difference between two treatments. Significance levels of 0.05 were applied to the results to determine their statistical significance.

Nucleotide accession numbers

The 19 nucleotide sequences determined in this study were deposited in the GenBank database under accession descried in Table 4.

Results

PAHs biodegradation

Fourteen EPA PAHs were observed with naphthalene not detected in initial soil (Table 1). According to Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines released by Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) (2004), this soil was not suitable for agricultural land uses as well as residential or parkland uses due to high concentration of PAHs, especially benzo[b]fluoranthene and benzo[a]pyrene.

Loss of total and individual PAHs was summarized in Table 1. After 30 days of incubation, microcosms receiving bioaugmentation showed a 35 ± 0% depletion in total PAHs. Benzo[a]pyrene and anthracene were the most degradable ones with 70 ± 8% and 72 ± 2% removed from soil, respectively. Compared with control, significant degradation was observed in both total PAHs (p < 0.01) and benzo[a]pyrene (p < 0.05) in bioaugmented microcosms. At the same time, only 16 ± 9% of total PAHs, 16 ± 0% of benzo[a]pyrene and 44 ± 15% of anthracene disappeared in biostimulated microcosms. No significant difference was observed between biostimulated and control microcosms.

Calculated degradation based on ring number of PAHs was described as Fig. 1. For biostimulated and control microcosms, percentages of degradation decreased in the following order: 3-ring > 4-ring > 5- and 6-ring, which coincided with the general idea that PAHs with less rings are more easily degradable. However, for bioaugmented microcosms, 5- and 6-ring PAHs were more degradable due to high removal of benzo[a]pyrene.

Genotoxic potential differences

Results from umu test showed that values of genotoxic factor for initial soil, biostimulated and control microcosms were all 12, while the bioaugmented microcosms had a lower value, i.e. 6. According to the definition of genotoxic factor, larger value denotes higher toxic potential (ISO 2000). So it seemed that inoculation of W5-2 decreased mutagenic potential of soil, which is consistent with the decreases of total PAHs and benzo[a]pyrene confirmed by of HPLC.

Enumeration of AHD

A miniaturized MPN method was employed to evaluate the bacterial potential of degrading PAHs. The results were described in Table 2. Compared with the initial soil, significant proliferation (p < 0.05) of AHD population was observed on all microcosms after 30 days incubation. Both bioaugmented and biostimulated microcosms showed more AHD (p < 0.05) compared with control, implying positive effect of nutrient (ground corn cob) on indigenous microbial population. Furthermore, there were more AHD in biostimulated microcosms than those receiving bioaugmentation, suggesting a weak impact on indigenous bacteria by Monilinia sp. W5-2.

Impact of mycoremediation on microbial community composition

Bacterial community profiles elucidated by DGGE are presented as Fig. 2A. As the initial soil was concerned, six bands consisted of the main bacterial population (band 1–6), showing a less diverse community. In the cases of biostimulated and bioaugmented microcosms, a significant shift in population structure was denoted by appearance of new bands. At the end of incubation, profiles for bioaugmented and biostimulated microcosms were highly similar, forming one cluster, while profiles for initial soil and control microcosms forming another (Fig. 3A). Indicated by Fig. 2B which shows the eukaryotic communities, differences were observed between initial soil, control microcosms and biostimulated and bioaugmented microcosms, with two clusters formed (Fig. 3B). So it is apparent that the addition of ground corn cob changed the indigenous microbial community greatly, and Monilinia strain W5-2 posed little impact on microbial community.

Based on DGGE profile, the microbial diversity was estimated (Table 3). After 30 days of incubation, bacterial communities diversity (elucidated by Shannon-Wiener index) in both bioaugmented and biostimulated microcosms increased significantly (p < 0.05). However, no significant difference was detected between bioaugmented/biostimulated and control microcosms (Table 3). At the other hand, there was no obvious change among fungal diversity index, though the species composition in mycoremediation microcosms shifted after 30 days incubation.

Bands retrieved and sequencing

Twenty three characteristic bands in bacterial DGGE profile were excised and subsequently sequenced. Nineteen sequences were retrieved successfully. The short fragments of bacterial 16S rRNA gene V3 region were compared with similar sequences by searching GenBank using BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997). While the short sequence was not adequate to specify a microorganism, the closest phylotype can be acquired by searching 16S rRNA gene database. Results of taxonomic information of bands are presented in Table 4.

Discussion

Presence of large number of appropriate microorganisms is key to successful bioremediation (Chang and Devinny 2000). Both biostimulation and bioaugmentation are among the most used techniques in bioremediation by promoting degradative microorganisms. Theoretically, PAHs-degrading microorganisms are ubiquitous at contaminated sites. Nevertheless, HMW PAHs-transforming bacteria are relatively rare in soil. For example, in the present study, increase of AHD in biostimulated microcosms did not result in significant decrease of 5- and 6-ring PAHs (Table 1). In this case, bioaugmentation should be considered.

Fungi as main soil microorganisms are important in the detoxification and cleaning up of contaminated soil (Bennet et al. 2002). Many fungi, such as WRF, have high potential in degrading PAHs (Andersson et al. 2003; Canet et al. 2001; D’Annibale et al. 2006; Gramss et al. 1999; Novotny et al. 1999; Potin et al. 2004). However, two effects of fungal remediation should be highlighted: removing of total/individual PAHs and effect on indigenous microorganisms, which combine to decide the potential of fungal remediation. In the present study, both PAHs removal and microbial effect of a filamentous indigenous soil fungus, Monilinia sp. W5-2 were monitored to test its remedial potential. Although specifically tracking of Monilinia sp. W5-2 was not available, the white filamentous mycelium was observed in bioaugmented microcosms after several days since inoculation, indicating a successful colonization of the inoculum.

After 30 days of incubation, significant removal was observed for total and individual PAHs in the bioaugmented microcosms, indicating the crucial role of Monilinia strain W5-2. Decrease of HMW PAHs in bioaugmented microcosms (Fig. 1) was also comparable with other literature (Potin et al. 2004). Although biostimulation did decrease PAHs to some extent, no statistical significant difference was found (Table 1).

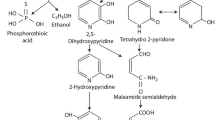

It is remarkable that inoculation of fungus led to more removal of benzo[a]pyrene and anthracene (70 ± 8% and 72 ± 2%, respectively) than other individual PAHs. We confirmed this with extracellular fluids (data not shown). It is reported that benzo[a]pyrene and anthracene have low ionization potentials (IPs) (7.11 eV and 7.43 eV, respectively.) (NIST 2006), which makes them susceptible to attack of ligninolytic enzyme such as laccase and MnP. Field et al (1992) and Collins et al (1996) reported that anthracene and benzo[a]pyrene can be transformed in liquid culture or culture fluid of several fungi; Steffen et al (2002) indicated that some fungi transform benzo[a]pyrene almost completely in liquid culture; a study previously conducted in our lab showed a positive correlation between IPs of individual PAH and degradation by a commercial laccase in reaction mix. In case of soil, fungi also showed preferential degradation of HMW PAHs in microcosm study (Potin et al. 2004). All of these implied ligninolytic enzymes’ role in mycoremediation. However, no significant correlation was observed between IPs and percentages of degradation in the present study.

Molecular weight, which also means bioavailablity of PAHs, is a crucial factor affecting the bioremediation of PAHs (Barnforth and Singleton 2005). In the case of control and biostimulated microcosms, only 2% and 13% of 5- and 6-ring PAHs were transformed, respectively (Fig. 1). Fungi can improve bioavailablity of HMW PAHs by releasing extracellular enzymes, penetrating into solid particles, or serving as vectors for the dispersion of pollutant-degrading bacteria (Kohlmeier et al. 2005). However, the mechanism of favorable HMW PAHs transformation by Monilinia strain W5-2 is to be explored.

The toxicity of PAHs metabolites is of particular concern (Barnforth and Singleton 2005). Bioassays provide important information for the assessment of bioremediation (Eisentraeger et al. 2005). Here we tested the genotoxicity of soils with a genetically modified organisms Salmonella typhimurium NM2009. Although the genotoxic factor is not a noncontinuous measure and cannot be evaluated statistically according to the international standard (Ehrlichmann et al. 2000), the decrease of genotoxic factor after introduction of Monilinia sp. W5-2 reveals partial detoxification of mycoremediation strategy. Similar results were also described by other authors (D’Annibale et al. 2006).

Exotic fungal inocula may have positive or negative effect on indigenous bacteria community (Andersson et al. 2003). As is well known, the synergistic effect and sequential fungal-bacterial degradation among microorganisms are important for mineralization of organic compounds (Johnsen et al. 2005), so shift in microbial community composition may have an important effect on mineralization of pollutants. In the present study, selective enumeration indicated a substantial increase of AHD in biostimulated and bioaugmented microcosms (Table 2). No significant difference was observed between bioaugmented and biostimulated microcosms. This result can be attributed to addition of ground corn cob, which may be served as carbon source to stimulate proliferation of indigenous bacteria.

It can be seen from DGGE profiles and sequences alignment that dominant bacterial species (bands 3–6) in initial soil are Bacillaceae (Fig. 2A), which are widely spread species in soil. After incubation, the bacterial diversity increased (Table 3) coupling with significant shift of microbial community composition in biostimulated and bioaugmented microcosms (Fig. 2); furthermore, the presence of Pseudomonadaceae, which is one of the main PAHs degrading taxonomic groups in soil (Johnsen et al. 2005), indicating increased abundance of potent PAHs degraders in soil bacteria population. There is only small difference between DGGE profiles for bioaugmented and biostimulated microcosms (Fig. 2 and 3), implying inoculation of Monilinia sp. W5-2 had little impact on microbial community composition. Therefore Monilinia sp. W5-2 is a promising candidate strain for bioremediation of PAHs-contaminated soil based on the high removal of PAHs as well as the negligible effect on indigenous microorganisms.

There are abundant fungi species with about 80,000 already named in our world (Bennet et al. 2002). Compared with this diverse kingdom, species of fungi used in bioremediation are still very less. To our knowledge, it is the first report that cleaning up PAHs-contaminated soil using Monilinia sp. Monilinia is not ligninolytic but cellulolytic fungus, which was reported that can produce oxidases such as cellobiose oxidase (Dekker 1980). Though mechanism of transformation, interaction with soil microorganisms, and other issues of are still to be elucidated, Monilinia sp. W5-2 is promising in bioremediation of PAHs contaminated soil due to its high potential in removing PAHs (especially benzo[a]pyrene), which leads to decreased ecological risks, and relatively less disturbance on indigenous microbial population. Our future studies will focus on the metabolism pathway of PAHs by Monilinia sp. W5-2 and field studies.

Conclusions

PAHs, especially HMW PAHs, are toxic persistent chemicals and recalcitrant to microorganism degradation, posing human health risks. There have been few reports describing efficient decontamination of HMW PAHs in natural soil system by bioremediation. In our study, bioaugmentation with autochthonous filamentous fungus, Monilinia sp. W5-2, removed HMW PAHs, in particular benzo[a]pyrene, greatly and no apparently negative effect on indigenous microbial community was observed, showing high potential in bioremediation. Biostimulation (addition of ground corn cob) can increase PAHs-removing potential by promoting indigenous AHD population, which would be beneficial to natural attenuation of pollutants in soil. In conclusion, fungal remediation is a promising strategy for bioremediation of PAHs-contaminated soil.

References

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25:3389–3402

Andersson BE, Lundstedt S, Tornberg K, Schnurer Y, Oberg LG, Mattiasson B (2003) Incomplete degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil inoculated with wood-rotting fungi and their effect on the indigenous soil bacteria. Environ Toxicol Chem 22:1238–1243

Andersson BE, Tornberg K, Henrysson T, Olsson S (2001) Three-dimentional outgrowth of a wood-rotting fungus added to a contaminated soil from a former gasworks site. Biores Technol 78:37–45

Barnforth SM, Singleton I (2005) Bioremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: current knowledge and future directions. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 80:723–736

Bennet JW, Wunch KG, Faison BD (2002) Use of fungi biodegradation. In: Hurst CJ (eds) Manual of environmental microbiology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C

Bogan BW, Lamar RT, Burgos WD, Tien M (1999) Extent of humification of anthracene, fluoranthene, and benzo[alpha]pyrene by Pleurotus ostreatus during growth in PAH-contaminated soils. Letters in Applied Microbiology 28:250–254

Canet R, Birnstingl JG, Malcolm DG, Lopez-Real JM, Beck AJ (2001) Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) by native microflora and combinations of white-rot fungi in a coal-tar contaminated soil. Biores Technol 76:113–117

CCME (2004) Canadian soil quality guidelines for the protection of environmental and human health: Summary tables. Updated. CCME, Winnipeg

Cerniglia CE (1997) Fungal metabolism of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: past, present and future applications in bioremediation. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 19:324–333

Chang S-H, Devinny JS (2000) Bioaugmentation for soil bioremediation. In: Wise DL, Trantolo DJ, Cichon EJ, Inyang HI, Stottmeister U (eds) Bioremediation of contaminated soils. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York

Coll PM, Fernandez-Abalos JM, Villanueva JR, Santamaria R, Perez P (1993) Purification and characterization of a phenoloxidase (laccase) from the lignin-degrading basidiomycete PM1 (CECT 2971). Appl Environ Microbiol 59:2607–2613

Collins PJ, Kotterman MJJ, Field JA, Dobson ADW (1996) Oxidation of anthracene and benzo[a]pyrene by laccases from Trametes versicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:4563–4567

Corgie SC, Fons F, Beguiristain T, Leyval C (2006) Biodegradation of phenanthrene, spatial distribution of bacterial populations and dioxygenase expression in the mycorrhizosphere of Lolium perenne inoculated with Glomus mosseae. Mycorrhiza 16:207–212

D’Annibale A, Rosetto F, Leonardi V, Federici F, Petruccioli M (2006) Role of autochthonous filamentous fungi in bioremediation of a soil historically contaminated with aromatic hydrocarbons. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:28–36

Dekker RFH (1980) Induction and characterization of a cellobiose dehydrogenase produced by a species of Monilia. J Gen Microbiol 120:309–316

Dilly O, Bloem J, Vos A, Munch JC (2004) Bacterial diversity in agricultural soils during litter decomposition. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:468–474

Ehrlichmann H, Dott W, Eisentraeger A (2000) Assessment of the water-extractable genotoxic potential of soil samples from contaminated sites. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety 46:73–80

Eisentraeger A, Hund-Rinke K, Roembke J (2005) Assessment of ecotoxicity of contaminated soil using bioassays. In: Margesin R, Schinner F (eds) Manual for soil analysis—monitoring and assessing soil bioremediation. Springer, Berlin

Field JA, de Jong E, Feijoo Costa G, de Bont JA (1992) Biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by new isolates of white rot fungi. Appl Environ Microbiol 58:2219–2226

Gramss G, Voigt KD, Kirsche B (1999) Degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with three to seven aromatic rings by higher fungi in sterile and unsterile soils. Biodegradation 10:51–62

ISO (2000) ISO 13829:2000(E) Water quality—Determination of the genotoxicity of water and waste water using the umu-test. ISO, Geneva

Johnsen AR, Wick LY, Harms H (2005) Principles of microbial PAH-degradation in soil. Environ Pollut 133:71–84

Juhasz AL, Naidu R (2000) Bioremediation of high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a review of the microbial degradation of benzo[a]pyrene. Int Biodeterio Biodeg 45:57–88

Kohlmeier S, Smits THM, Ford RM, Keel C, Harms H, Wick LY (2005) Taking the fungal highway: mobilization of pollutant-degrading bacteria by fungi. Environ Sci Technol 39:4640–4646

McErlean C, Marchant R, Banat IM (2006) An evaluation of soil colonisation potential of selected fungi and their production of ligninolytic enzymes for use in soil bioremediation applications. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek Int. J Gen Mol Microbiol 90:147–158

Muyzer G, de Waal EC, Uitterlinden AG (1993) Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 59:695–700

NIST (2006) Chemistry WebBook. http://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/ie-ser.html. Cited 30 Oct 2006

Novotny C, Erbanova P, Sasek V, Kubatova A, Cajthaml T, Lang E, Krahl J, Zadrazil F (1999) Extracellular oxidative enzyme production and PAH removal in soil by exploratory mycelium of white rot fungi. Biodegradation 10:159–168

Pickard MA, Roman R, Tinoco R, Vazquez-Duhalt R (1999) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolism by white rot fungi and oxidation by Coriolopsis gallica UAMH 8260 laccase. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:3805–3809

Ping LF, Luo YM, Zhang HB, Li QB, Wu LH (2007) Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in thirty typical soil profiles in the Yangtze River Delta region, east China. Environ. Pollut 147:358–365

Plaza G, Nalecz-Jawecki G, Ulfig K, Brigmon RL (2005) Assessment of genotoxic activity of petroleum hydrocarbon-bioremediated soil. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 62:415–420

Potin O, Rafin C, Veignie E (2004) Bioremediation of an aged polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)-contaminated soil by filamentous fungi isolated from the soil. Int Biodeterior Biodeg 54:45–52

Sigler WV, Turco RF (2002) The impact of chlorothalonil aplication on soil bacterial and fungal populations as assessed by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl Soil Ecol 21:107–118

Steffen KT, Hatakka A, Hofrichter M (2002) Removal and mineralization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by litter-decomposing basidiomycetous fungi. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 60:212–217

Thorn G (1997) The fungi in soil. In: van Elsas JD, Trevors JT, Wellington EMH (eds) Modern soil microbiology. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York

Tortella GR, Diez MC (2005) Fungal diversity and use in decomposition of environmental pollutants. Crit Rev Microbiol 31:197–212

Wei JC (1979) Manual for Fungi identification. Shanghai Sci & Tech Press, Shanghai

Wilms R, Kopke B, Sass H, Chang TS, Cypionka H, Engelen B (2006) Deep biosphere-related bacteria within the subsurface of tidal flat sediments. Environ Microbiol 8:709–719

Wrenn BA, Venosa AD (1996) Selective enumeration of aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbon degrading bacteria by a most-probable-number procedure. Can J Microbiol 42:252–258

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants from Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2002CB410809) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (40432005). We thank Dr. Y. Oda, Osaka Prefectural Institute of Public Health (Osaka, Japan) for kindly supplying S. typhimurium NM2009. We also thank Prof. Yunlong Yu, Zhejiang University (Hangzhou, China) for help in identifying fungus W5-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Luo, Y., Zou, D. et al. Bioremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contaminated soil with Monilinia sp.: degradation and microbial community analysis. Biodegradation 19, 247–257 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-007-9131-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-007-9131-9