Abstract

Wildlife crime is increasingly gaining prominence in global environmental debates. The crime, generating huge financial returns to few individuals, has far reaching implications on ecology, economy and global security. The seriousness of these implications provides sufficient rationale for reconsidering and intensifying efforts to combat this crime. However, these efforts are compromised by a number of challenges, though opportunities for success exist. This paper presents some of these challenges and opportunities available for reversing the trend of wildlife crime in Tanzania. The challenges presented include poverty, high profit associated with illicit trade on wildlife, poor governance and corruption, minimal budget and inadequate institutional support, political interference and low employee morale, minimal benefits to local communities, human population growth, climate change and HIV/AIDS pandemic. Opportunities identified include increased public awareness, growing global political concern and commitment, presence of relevant policies, programmes and strategies along with international agreements supportive to species protection. Before embarking on challenges and opportunities, the paper provides an overview of Tanzania’s wildlife resources, status and trend of this crime. In conclusion, the paper underscores the gravity of the problem and its implications and offers some recommendations for improving the situation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wildlife crime refers to any environmental related crime that involves the poaching, capture, collection or processing of animals and plants taken in contravention of national, regional or international laws, and any subsequent trade in such animals and plants, including their derivatives or products (Cooper et al. 2009). The crime also includes activities that affect wildlife more indirectly, such as pollution of waterways that results in damage to fish or other wildlife species, or the destruction of protected wildlife habitats (Blevins and Edwards 2009). In this paper, the term ‘wildlife crime’ is used more restrictively to emphasize poaching and illicit trade.

Wildlife crime is one of the most lucrative transnational crimes and ranks fourth after drugs, arms and human trafficking (CITES 2013; UNODC 2015). Financial gains from international illicit wildlife trade is estimated to range between US$8 and US$10 billion per annum (CITES 2013; UNODC 2015). Its main drivers, among others, include poverty, human population growth, culture and the exponential growth in consumer demand and trade in these species’ body parts for fashion and medicine (Ripple et al. 2015; TRAFFIC 2012). This crime has far reaching implications on ecological, social, economic and political facets.

The ecological implication of wildlife crime emanates from the role that some wildlife species play as keystone and umbrella species. Unfortunately, most of the keystone and umbrella species are economically high value species targeted for commercial poaching such as elephants, rhino and tiger. A keystone species is defined as a species with key roles in community structure and/or ecosystem functioning (Mouquet et al. 2013). Removal of a keystone species has, therefore, a huge downstream effect in the ecosystem and can lead to disappearance of the entire community. A recent study in South Africa’s Kruger National Park where rhino poaching has shown undesirable effect on the ecological functioning of savannah ecosystem elucidates this (Cromsigt and te Beest 2014).

The umbrella species are species of common conservation concern receiving higher priority in conservation. They are selected for making conservation-related decisions, typically because protecting them indirectly protects the many other species that make up the ecological community of their habitats (Roberge and Angelstam 2004). Basically, the concept of umbrella species targets the species with a large-home range size, where several other species are hosted (ibid.). Therefore, a large number of co-occurring species benefit from conservation efforts and priorities geared towards umbrella species, implying that removal of an umbrella species from an ecosystem precludes the conservation of other species.

Wildlife crime undermines the economic prosperity of many countries relying on wildlife-based tourism as its important source of revenues. Tourism is a powerful vehicle for economic growth and job creation all over the world (WTTC 2013; Christie et al. 2014). In Sub-Saharan Africa, where over 70 % of tourism is wildlife-based, the industry plays a key role in energizing economies and fuelling the economic transformation. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, receipts from tourism in 2012 amounted to over US$36 billion and its direct contribution to the region’s GDP was 2.8 %. Total contribution, including direct, indirect, stood at 7.3 % of GDP (WTTC 2013). The Council’s projections for the next 10 years indicate that 3.8 million jobs will be created by the industry in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Besides posing ecological and economic burdens, wildlife crime is also regarded as a security and humanitarian issue attested to fund political conflicts and terrorism in Africa (Global Financial Integrity 2012; Nellemann et al. 2014; Vira and Ewing 2014; Schiffman 2014; Kalron 2012; Somaville 2014). Somalia’s al-Shabaab is reported to earn about 40 % of its revenues through poaching and trading ivory obtained in Northern Kenya (Kalron 2012). Uganda’s Lord Resistance Army (LRA) and rebels in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are linked to decimation of thousands of wild animals in DRC’s Garamba National Park (Marais et al. 2012). Darfur’s Janjaweed has been targeting elephants in Chad, Cameroon, the Central Africa Republic and northern Democratic Republic of the Congo (Saah 2012; Somaville 2014) while Nigeria’s Boko Haram has been implicated with poaching of elephants in Cameroon (Tumanjong 2012; US Embassy 2012).

The impact of Civil wars and insurgency on wildlife has been manifested by decline of wildlife species. For instance, operations of Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), caused a dramatic decline of elephants from more than 130,000 in 1986 to 5000 (3.9 % only) in 2012 (Holland 2012). In February 2012, Sudanese rebels killed over 300 elephants in Cameroon’s Bouba N’Djida National Park. This was 80 % of the park’s population. In response to this, Central African countries deployed as many as 1,000 soldiers and law-enforcement officials equipped with helicopters, night vision gear, and scores of jeeps to protect the region’s last remaining elephant populations (WWF 2012).

Efforts to curb the problem of wildlife crime have been in place for several decades at local and global levels. These efforts, among others, have included establishment of protected areas, formulation of policies, enacting laws and conducting campaigns against the crime. However, numerous challenges are compromising these efforts although opportunities for success exist. Uncovering these challenges and opportunities is crucial and an entry point to devising effective mitigation and corrective measures.

Tanzania: wildlife resources, status and trend of poaching

Tanzania, covering some 945,087 Km2, is home to a variety of wildlife species including 375 species of mammals, 1056 species of birds, 132 amphibians, 335 reptile species and over 10,000 vascular plant species (UNEP-WCMC 2004). Scientific evidence indicates that Tanzania ecosystems contain several other species which are yet to be discovered. For example, the latest studies on the faunal richness of the tropical moist forests of the Eastern Arc Mountains show the discovery of 27 vertebrate species that are new to science; and 14 other species that were previously unknown to exist in the area (CEPF 2005; EAMCEF 2012).

Over 40 % of the country’s land area is under legal protection as national parks, nature reserves, game reserves, forest reserves, game controlled areas, Ramsar sites and wildlife management areas. Beyond ecological reasons, conservation efforts in Tanzania are mainly justified by economic contribution through tourist hunting, live animal trade and photographic tourism. Between 2009 and 2013, Wildlife Division earned about US$ 100.8 million through tourist hunting (US$ 84.7 million), live animal trade (US$ 0.4 million) and photographic tourism (US$ 15.7 million) (WD 2013a). Wildlife-based tourism provides one of Tanzania’s largest and most rapidly expanding sources of national revenue contributing about 25 % of foreign exchange earnings.

Wildlife crime, among other threats, undermines the economic potential presented by wildlife resource. The most notable wildlife crime is poaching for subsistence and commercial. For years, subsistence poaching has basically been conducted by poor people to meet their dietary and subsistence requirements (Loibooki et al. 2002; Kideghesho et al. 2005; Jambiya et al. 2007; Martin et al. 2012). However, under abject poverty in rural areas and increasing demand in urban areas, poaching for subsistence is no longer limited for the pot, but has been commercialized and, therefore, affecting the population of several mammal species (Holmern et al. 2007; Ndibalema and Songorwa 2007; Mfunda and Roskaft 2010; Martin 2012).

Another form of poaching is commercial poaching. In Africa, elephants and rhinos are the most targeted species because of their ivories and horns, respectively. Illicit trade in these parts is one of the most lucrative forms of trade globally. Demand for ivory in Asian countries is mainly motivated by the perception that ivory is the “perfect gift,” due to its rare, precious, pure, beautiful and exotic nature and more importantly, the status that ivory confers to both the giver and the recipient of the gift (Strauss 2015). On the other hand, the main driver for a demand on rhino horn is its perceived medicinal and aphrodisiac qualities (Emslie and Brooks 1999; Ellis 2005). The first highest poaching crisis in history for these species occurred between 1970s and 1980s. This crisis affected virtually all African countries. The increased demand for elephant tusks and rhino horns in Asian nations and global economic recession were the main causes for this crisis.

Global economic recession had implication on budgetary allocation for natural resources sector. For example, between 1976 and 1981, about US$ 52 million (1.2 % only of the budget) was allocated for the entire natural resources sector (wildlife, forestry and fisheries) in Tanzania. The budget for wildlife sub-sector has, since then, continued to decline gradually. For example, allocation for 1982–1985 was US$ 14.03 m; 6.81 m (1985–1986); 2.88 m (1986–1993) and 0.23 m (1993–1996) (WSRTF 1995). While cost for effective control of commercial poaching in Africa was estimated to range from US$ 200 to US$ 400/km2 (Leader-Williams et al. 1990), the amount allocated for the same in Tanzania was extremely low. For example, the amount allocated for Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania’s biggest strongholds for elephants and rhinos, was US$ 3/km2 (Baldus et al. 2003). The protected areas were also understaffed with inadequate equipment. For example, the staff area ratio (person:km2) was 1:130 instead of the ideal ratio of 1:25 and there was only one vehicle per each administrative region (Masilingi 1994), regardless of the size. Sizes for some regions were as big as 80,000 km2.

The widespread poaching, eased by inefficient law enforcement, caused a dramatic decline of elephant and rhino populations. The country’s elephant population plummeted to less than 30 % from 203,000 in 1977 to 57,334 in 1991 (IUCN 1998) while only 275 rhinos remained in 1992 compared to 3,795 in 1981, a loss of over 93 % of the population (Sas-Rolfes 2000).

Stringent measures adopted at the national and global levels had significant impact on reducing poaching in 1990 s. At the national level the government launched a nationwide operation, code-named ‘Operation UHAI’, which involved officers and soldiers from Tanzania People’s Defence Forces, Tanzania Police Force and wildlife authorities. At the international level, CITES—the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna—banned the ivory trade, and thus stemming the crime across the whole continent.

The impact of the above measures had persisted for over a decade, before another upsurge of elephant and rhino poaching became apparent. The Tanzania’s elephant population dropped from 130,000 in 2002 to 109,000 in 2009, with an average of 30 elephants being killed every day, or about 850 per month. Between 2010 and 2013, there were 208 incidences within and eight outside Tanzania that resulted to seizures of 13.4 and 20.7 tones of ivory, respectively (WD, unpublished data). The recent census has revealed a further drop of elephant population to 43,521 (about 60 % in five years) (The Ecologist 2015).

Following these massive killings of elephants, Tanzania was grouped as one of the worst offenders in the ivory trade during the 2013 CITES conference held in Bangkok, Thailand. The country, along with Kenya, Uganda, Malaysia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Thailand and China were singled out as “The GANG OF EIGHT”, accused of failing to do enough to tackle the illegal trade in ivory (Ruso 2014).

Wildlife crime and country’s tarnished image associated with this crime have affected Tanzania due to sanctions imposed over legal wildlife trade. For example, in March 2010, Tanzania applied to CITES to sell its ivory stockpile in order to generate proceeds that would be used exclusively for conservation, community conservation and development programmes. However, this proposal was rejected, one of the reason cited being poaching situation. In April 4, 2014, the US Fish and Wildlife Service suspended imports of sport-hunted African elephant ivory taken during calendar year 2014 in Tanzania and Zimbabwe. The reasons given for this were catastrophic elephant population declines caused by uncontrolled poaching, questionable management practices, a lack of effective law enforcement and weak governance (US-FWS, 2014). On July 2, 2015 the European Union (EU), basing on recommendations from its Scientific Review Group (SRG) banned the import of hunting trophies of African elephants from the United Republic of Tanzania and Mozambique (EU 2015). Before the decision, eighteen international environmental and conservation organizations were pressurizing the EU governments to halt all exports of raw ivory (EIA 2015).

Wildlife crime has also affected the famous Tanzanian protected areas, which are internationally recognized for their global outstanding values. For instance, Selous Game Reserve was designated as UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982 due to the diversity of its wildlife including being a stronghold for African elephants and rhinos. However, following widespread poaching and, consequently, dramatic decline in the wildlife populations, especially for elephants and rhino, the 38th session of the World Heritage Committee held on 18th June 2014 inscribed the Reserve on the List of World Heritage in Danger. The Reserve has lost about 90 % of its rhino and elephant populations since 1982 (UNESCO 2014).

Challenges in curbing poaching

Increasing wildlife crime in Tanzania does not imply inaction. There are interventions geared towards this problem. However, these interventions are both inadequate and ineffective. This section explores some of the challenges in reversing the trend of wildlife crime, despite the intervention employed.

High economic returns from wildlife crime

High profits generated through wildlife crime provide incentive for different cadres of people to engage in this crime, both globally and locally. The monetary value of illegal wildlife trade globally is estimated to range from US$8 to US$10 per annum, making it one of the most lucrative transnational crimes after drugs, arms and human trafficking (CITES 2013; UNODC 2015). The high economic returns associated with wildlife crime can mainly be attributed to rising demand and, consequently, price for wildlife products in Consumer countries. For example, in China the price for ivory tripled in a period of four years from US$ 750/kg in 2010 to USD$ 2,100/kg in 2014 (Stile 2014).

At the local level, the returns from this crime exceed other legal economic endeavours by far, making it an important livelihood and coping strategy among the poor communities. Recent comparison of the returns from illegal hunting and other livelihood activities in western Serengeti revealed that the latter had minimal financial risks and more monetary rewards (Knapp 2012). While majority of poachers (96 %) earned an annual average income of US$ 425 per annum from wildlife poaching, revenues from crop selling, livestock selling and other trade or small business were US$ 79, US$ 61, and US$ 118, respectively (Fig. 2).

Government efforts aimed at motivating people to refrain from wildlife crime through benefit-sharing schemes, have led to unexpected outcomes. These benefits have often been too minimal to outweigh the social and economic costs of living with wildlife, to compete with benefits from ecologically damaging activities including poaching, and to reduce poverty among the local communities (Kideghesho et al. 2005). For instance, previous studies in Serengeti, which assessed the impact of provision of bushmeat to local communities from wildlife cropping scheme through Serengeti Regional Conservation Project, found that the benefits from illegal hunting were 45 times those provided by the Scheme (Holmern et al. 2002; Kideghesho et al. 2005). Emerton and Mfunda (1999) estimated the costs incurred by local communities from wildlife conservation through opportunity cost and property damage to be 250 times the benefits earned from conservation initiatives (Fig. 3).

Household poverty and unemployment

There is increasing consensus among the scholars that unemployment, poverty and crime are inextricably linked (Becker 1968; Block and Heineke 1975; Bekerytė 2013; Kelly 2000). Becker’s economic theory of crime (1968) assumes that people resort to crime only if the costs of committing the crime are lower than the benefits gained. Those living in poverty, therefore, have a much greater chance of committing property crime (Kelly 2000; Zhao et al. 2002). Crime offers a way in which impoverished people can obtain material goods that they cannot attain through legitimate means.

Despite her abundant natural resources and development opportunities ranging from minerals, wildlife, forests, fish, and diverse climate and geographical features, Tanzania is one of the poorest countries in the world. Her GDP per capita income (as of 2015) was US$998, placing it in the 159th position out of 191 countries of the world (World Bank). The public Debt is estimated at 42.7 % (CIA 2015). About 12 million people are considered to be poor (World Bank 2015) and unemployed persons (as of 2011) were 2,368,672 persons—equivalent to 10.7 % of the labour force population (NBS 2011). Current unemployment rate is 11.88 % (NBS 2015). The 2011/12 National Household Budget Survey estimates the basic needs poverty line and food poverty line at 36,482 Tanzanian Shillings (USD 24) and 26,085 Tanzanian Shillings (17 USD) per adult equivalent per month, respectively (NBS 2013). Using these two poverty lines, Tanzanian population falling below the basic needs poverty line is 28.2 percent, while 9.7 percent falls below the food poverty line.

The statistics on unemployment and poverty above indicate that potential for crime in Tanzania is high. Wildlife crime is one form of property crime occurring in Tanzania. Numerous research findings indicate that illegal hunting in Tanzanian protected areas is pursued as a coping strategy against poverty and as an employment opportunity for a growing population of youth (Loibooki et al. 2002; Kideghesho et al. 2006; Bitanyi et al. 2012; Knap 2012; Fyumagwa et al. 2013).

Inadequate budget for conservation and insufficient support from other government institutions

Wildlife sector generates substantial revenues for treasury and is considered as one of the giant economic sector, contributing 17 % of the GDP. However, only meagre financial resources are ploughed back for protection of species and management of the protected areas, probably due to country's poor performance economically in the face of other competing government priorities. For example, in order to effectively execute its activities for a period of three years (2010–2012), the Wildlife Division required about US$ 60.7 million. However, the amount allocated was US$ 6.5 million, 10 % only of the requirement (WD 2013a). Lamenting in a social media network (Wildlife Professional Forum WhatsApp Group, in July 15, 2015), one of the senior officials in the Wildlife Division said:

Am trying to think loudly, the huge amount of revenues the sector generates. It goes to the treasury, but what is ploughed back for conservation work is a shame! Which language should we use so that policy makers understand? They are on the frontline in the media complaining about increasing poaching while there is nothing they do to end it. What government is doing is like milking a cow without feeding it.

Another official expounded this by saying:

Imagine a game reserve covering 4000 km2, with 60 rangers but with only seven houses. So most of the rangers are living in the villages where security is unguaranteed and it’s impossible to monitor their ethical conduct. You have only one vehicle for patrol which is not road worth most of the time and with unreliable fuel supply. While two hundred poachers enter the game reserve per month, available resources allow only eight rangers to conduct 10 patrols per month and the rest remain idle. If all rangers are to patrol on foot they can only cover 35 km2 out of 4,000 km2. At the same time you have thousands of livestock herds inside the reserve, some 50 km2 from the reserve headquarters.

Minimal budget allocation to wildlife sector cripples law enforcement activities including patrols, prosecution, investigation and intelligence. Further to minimal budget, the existing manpower and equipment are inadequate (Table 1). The international standard staff area ratio recommended for effective law enforcement is one person patrolling 25 km2. However, with the current low number of staff one person patrols an area of 169 km2.

Along with minimal budget allocation, wildlife sub-sector faces a general lack of support in its war against wildlife crime from the public and institutions including government institutions. This situation renders the Wildlife Division unable to enforce law effectively as most of the servants remain demoralized.

One example of insufficient support from the government institutions is reluctance of the Treasury to grant tax exemption on vehicles and firearms imported by or donated to Wildlife Division for law enforcement (Pers. observations, 2013). Surprisingly, the same authority has been reported to grant tax exemptions to multinational companies on grounds of attracting and retaining greater levels of Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs). However, analysts argue that the benefits of doing this are considerably exaggerated and the costs are mostly underrated (Policy Forum 2012, 2013). According to the 2013/14 Budget Speech, tax exemptions for 2011/2012 financial year amounted to 4.3 % of the GDP (URT 2013). The 2011 Controller and Auditor General Report cited tax exemptions as one of the tax loopholes that benefit able people and multinational companies which should pay tax (CAG 2011).

Minimal budget allocation for wildlife protection and heavy taxation imposed on wildlife authorities over equipment imported or donated for anti-poaching operations can hardly overcome the highly equipped poachers using sophisticated military weapons. The killing of a British anti-poaching pilot, Roger Gower, on January 29, 2016 illustrates poachers’ military strength. Poachers fired on aircraft and killed Captain Gower during a coordinated effort with the wildlife authorities to track down and arrest criminals who killed three elephants in Maswa Game Reserve, near Serengeti National Park (ITV, January 30, 2016).

Political interference and low employee morale

Efforts to curb wildlife crime are also hindered by political interference when political interests seem to override the professionalism (URT 2013; LHRC 2014; Kideghesho 2015). Some politicians frustrate these efforts on grounds of defending their voters. For instance, politicians have often stood for people who are living and earning their livelihoods illegally inside the protected areas and have been putting pressure on government to degazette some or parts of the protected areas (URT 2013; Kideghesho 2015). In a recent study, sought to understand perceptions of the staff working in Tanzania national parks and wildlife division towards the role of politicians in conservation, over 75 % (n = 120) described politicians as a constraint to conservation efforts, accusing them of unfair condemnations and false allegations (Kideghesho, unpublished data). This scenario causes demoralization and fear of victimization among the hardworking, committed, loyal and principled servants (Kideghesho 2015; Laing 2015; Songorwa 2015).

The political interference on the war against wildlife crime is also corroborated by the Parliamentary Committee on Land, Environment and Natural Resources Report on Anti-poaching Operation code-named Operation Tokomeza Ujangili (URT 2013). The Operation was a planned nationwide operation to combat poaching which was launched in 2013 in response to rampant poaching. Tokomeza Ujangili are Swahili words for Eliminate Poaching.The Report identified government officials and Members of Parliament for sabotage of this Operation. According to Report, some Members of Parliament (MPs) and government officials protected poachers whom they had close ties with. The Operation was prematurely terminated following allegations from politicians who decried gross violation of human rights. However, the report seemed to have been biased as only wildlife officials were implicated with deficiencies linked to Operation regardless the fact that the operation was led by Tanzania People’s Defence Forces (TPDF). The Army and other security and judiciary agencies had about 65 % of the participants in the operation (URT 2013),

However, while the tendecy has been for politicians to defend people engaging in wildlife-related crimes on grounds of human rights, they hardly commend a good job done by wildlife staff and turn a blind eye to problems that wildlife servants encounter. For instance, in the past 15 years, poachers have killed over 30 wildlife officers in Selous, Moyowosi, Maswa, Mpanga-Kipengere, Rukwa-Likwati, Mkungunero, Kijereshi, Burigi-Biharamulo Game Reserves, JUKUMU Wildlife Management Area, Kilimanjaro National Park and the district councils of Meatu, Simanjiro, Urambo and Kondoa (Wildlife Division, unpublished data). Some of these killings occurred just few days before the parliamentary session. One would have expected parliamentarians to take advantage of the session to condemn these killings but this did not happen. Surprisingly, the comments of the parliamentarians on budget speech for the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism attacked the wildlife employees for violation of human rights—simply bracing the ‘blame the victim’ scenario. The quotation from a wildlife ranger below expounds the situation:

Wildlife rangers are brutally being killed or wounded by poachers and trespassers who graze livestock illegally in the Reserve. Our politicians remain silent, no sympathy. When rangers are unfairly implicated with false and unfounded allegations such as raping, robbery, bribery and killings, the politicians shout and call for our dismissal from the job (A ranger in Burigi-Biharamulo Game Reserve, 2013).

A Senior wildlife Officer lamented through a social media (Wildlife Professional Forum WhatsApp Group, 20 July, 2015) by saying:

For us conservation is like offering a church service where you accept suffering in order to earn rewards after death. Our job is very risky, the working environment is very poor, we are grossly underpaid and ill-equipped. Yet we are very unpopular before the public and politicians.

These words were supported by Michel Matheakis, one of the conservationists and investor in wildlife sector:

No political campaign can have conservation as the main theme as conservation is unpopular with masses and therefore can cost too many votes.

On December 29, 2012, sixty days after termination of Operation Tokomeza, the government through the then Deputy Minister for Natural Resources and Tourism issued a press release indicating an escalation of wildlife crime, citing examples of events that occurred after termination (Box 1). Presumably, this resulted from self-confidence instilled among the criminals that they had full support from some powerful politicians.

Human population growth

The population of Tanzania has almost quadrupled since 1967. It increased from 12 million people in 1967 to 44.9 million in 2012 (URT 2015). With annual growth rate of 3.1 %, the projections for years 2025, 2035 and 2050 are 69.3, 102.7 and 129.1 million, respectively (Fig. 2). High human population, coupled with poverty and limited employment opportunities increases demand for resources and high possibility for engagement in criminal activities. The increased number of idle youth, who are frustrated and disillusioned can easily be manipulated by rich people and participate in wildlife-related crimes as they try to survive in an environment where opportunities and resources are unequally distributed.

The impact of population growth as a driver for wildlife crime is more evident in regions bordering the wildlife protected areas (Campbell and Hofer 1995; Kideghesho et al. 2005; Knapp 2012; Metzger et al. 2010). Numerous studies have indicated a significant correlation between human population growth in these areas and illegal hunting. For example, the rapid population growth in and around the Great Serengeti Ecosystem (Table 2) has created a huge demand for bushmeat which is used as a coping strategy against poverty and lack of employment (Campbell and Hofer 1995; Loibooki et al. 2002; Kideghesho et al. 2005; Knapp 2012; Bitanyi et al. 2012).

It is not only the population growth in the vicinity of protected areas that exacerbates wildlife crime. As wild meat is increasingly being commercialized (ibid), areas far away may also bear an impact since they are important market for wildlife products. Population size influences demand and price. Rise in price incentivizes poaching to supply more products to potential consumers.

Immorality and corruption

USAID (1999) defines corruption as the misuse of public office for private gain, including but not limited to, embezzlement, nepotism, bribery, extortion, influence peddling and fraud. Corruption arises in both political and bureaucratic offices and can be petty or grand, organized or disorganized. It undermines economic development in terms of efficiency and growth, affects equitable distribution of resources across the population, increases income inequalities, undermines the effectiveness of social welfare programmes and ultimately retards the levels of human development.

In addition to economic and human development, corruption has detrimental ecological consequences. It is one of the main factors hindering the efforts geared towards combating wildlife crime globally (Smith and Walpole 2003; WWF 2012). It is ranked the greatest threat to wildlife in developing countries (Smith et al. 2003). Smith et al. (2003) identify diversion of conservation funds for personal gains in African countries as the biggest problem weakening the law enforcement and, therefore, causing dramatic decline of elephant and black rhinoceros populations. They correlate the most corrupt countries with the highest failure in protecting their important species and habitats. Corruption eases poaching and transactions between supply, transit, and demand countries (Global Financial Integrity 2011).

In Tanzania, corruption is not uncommon. It is a dominant theme in the media, academia, political and religious forums. The country ranked 119th out of 175 countries in the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) and scored 31 (Transparency International 2015). The CPI measures “the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist among public officials and politicians. High numbers indicate less perception of corruption, whereas lower numbers indicate higher perception of corruption (Transparency International 2011). Corruption affects virtually all sectors, including natural resources. Most of the incidences of wildlife crime that Tanzania has been implicated with can hardly be explained without linking them with corruption taking place within and outside the country. For instance, it is unlikely that tons of ivory from 1077 elephants that were killed in different parts of Tanzania between 2010 and 2013 (WD 2013b) reached the market through transit countries undetected by the wildlife rangers, general public, security, police and custom officials. Likewise, the 2010 scandal of smuggling 140 live animals of 14 different species to Doha, Qatar through Kilimanjaro International Airport using the aircraft belonging to Qatar Army raises eyebrows over integrity of officials entrusted with public offices.

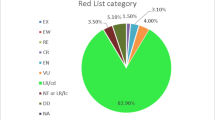

Substantial government revenues are lost through high level of corruption and, therefore, undermine government’s efforts to employ adequate staff, pay sufficient remuneration to existing staff and provide social services to its people. For instance, the recent minimum monthly salary for civil servants (as of 2014) is Tanzanian Shillings 240,000 or US$ 120. This amount is too little to cater for daily individual and household requirements such as food, fare to and fro the job, schooling for children, house rent, clothes, treatment, electricity and water. Poor servants entrusted with the task of safeguarding the wildlife resources, can easily fall into a trap of criminal poaching syndicates by accepting bribery and turn a blind eye to illegal killings and trade in order to complement their meagre salaries. Similarly, poor households and unemployed people resort to poaching in order to cope with economic hardships (Loibooki et al. 2002; Kideghesho et al. 2005) (Fig. 1).

Contribution of different economic activities to local economy in western Serengeti. Source Knapp (2012)

Tanzania population prospects 2015–2060. Source United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2012)

Schematic presentation of the implications of wildlife crime economically ecologically, politically and security-wise. Source Kideghesho (2016)

Political instability and the influx of refugees

Political unrest and civil wars have remained a sad reality in the Eastern and Central Africa countries, particularly Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. Tanzania, being a neighbour and a signatory to the region and international agreements on the rights and welfare of refugees and asylum seekers, had hosted thousands of the refugees from these countries.

Political instability has a bearing on population growth. Studies indicate that in the early 1990s some areas of western Tanzania had their populations increased by almost 200 % within a month due to refugee influx following genocide in Rwanda. According to Akarro (2001), human population in eleven wards of Kigoma Region increased by 172 % (from 217,095 to 590,308 people) in October 1993. In August 1994, 16 wards of Kagera Region were recipient of 467,670 refugees, who formed 64 % of the total population. In 1994, 500,000 refugees formed 72 % of the population of Ngara District (Akarro 2001). Few months later, the refugee population grew to 800,000.

Besides jeopardizing security of people and property, refugees have engaged in wildlife crimes that have led to serious ecological problems including decimation of large herbivores (Table 3). Poaching and wildlife trade had intensified in protected areas close to refugee camps. A massive scale of poaching was reported few months after arrival of refugees, where about 60 wild animals were illegally hunted per week to supply meat in the two main refugee camps of Benaco and Kilale Hill (KEP 1997). The major drivers behind poaching were human population concentrations, fluctuating food supplies and locally available wildlife populations in the absence of affordable and alternative meat protein (Jambiya et al. 2007).

The civil wars in Burundi and Rwanda ended in early 2000 and the majority of refugees returned to their home countries. However, peace that prevailed in Burundi for over a decade has been disrupted following President Piere Nkurunziza’s recent decision to run for a third term in office during the upcoming presidential election. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) statistics indicate that over 80,000 Burundians have fled their country and entered Tanzania from May 1 to July 13, 2015 (UHCR 2015). As a result of the continued volatile situation, UNHCR forecasted that the number was likely to increase from to between 250,000 and 500,000 (Grozdanic 2015). Based on the previous experience, similar environmental problems including poaching of wildlife are quite probable.

Climate change and HIV/AIDS pandemic

The influence of climate change and HIV-AIDS pandemic on wildlife crime can be derived from the impacts of the two in exacerbating poverty and vulnerability. Poor crop yield and death of livestock due to unfavourable climatic condition and, subsequently, food insecurity and lack of income forces people to search for alternatives including killing wildlife for protein and cash. Numerous studies have cited HIV/AIDS pandemic as one of the emerging drivers of household poverty (see e.g., Whiteside 2002; Baier 1997; Rugalema 1999) following loss of family members who are breadwinners (Kideghesho and Msuya 2012). As shown earlier, when alternative and sustainable means to sustain subsistence and income needs are closed people tend to switch to wildlife crime.

Furthermore, misconception among the people that, organs of some wildlife species can treat some chronic diseases subjects these species to poaching. For example, between 2004 and 2008, mass poaching of giraffes was reported in Monduli District and the West Kilimanjaro Wildlife Corridor—striding between Arusha and Kilimanjaro National Parks following emerged belief that the brains and bone marrow of the species could treat HIV-AIDS (Arusha Times 2004; Kideghesho and Msuya 2012; Muller 2008).

Opportunities

Despite the challenges, there are numerous opportunities that Tanzania and other countries can capitalize on to remedy the current trend of wildlife crime. Growing public awareness; presence of relevant policies, plans and strategies; regional and global agreements; growing international concern; commitment and support from international organizations and agencies are some of the opportunities presented here.

Increasing public awareness

Growing public awareness on factors undermining social welfare and national development, which indirectly facilitate wildlife crimes, provides motivation in combating drivers of wildlife crime. There is increasing public concerns over poor government performance on health, education and infrastructure sectors. These concerns are often linked with the wealth of the country in terms of natural resources including wildlife. Public awareness and concerns are crucial in exerting pressure for government to improve its governance systems.

Relevant policies, plans, programmes and strategies

Tanzania has put in place good and relevant policies, plans, programmes and strategies aiming at addressing the challenges of wildlife crime and its drivers. Wildlife policy of Tanzania recognizes wildlife crime as a major problem plaguing the natural resources sector and specifies a number of strategies to defeat this problem. The Policy affirms that:

The government will strengthen its capabilities to carry out anti-poaching operations effectively with the aim to reduce and ultimately eliminate illegal taking of wildlife resources. Incentive measures will also be explored and applied in order to encourage compliance of the law. (URT 2007:22).

Besides the sectoral policies, other government policies, programmes and strategies have synergistic and complementary effect for reducing the problem of wildlife crime through addressing the drivers of the crime. For instance, policies and strategies for poverty reductionFootnote 1 can play crucial role in transforming behaviours of the people who are forced into a crime in order to survive.

However, the problem has always been ineffective implementation of these policies and plans for a number of reasons including lack of resources and governance problems. Creation of enabling environment for implementation of these policies and plans are key in stemming wildlife crime and its drivers.

Regional and global agreements

Tanzania is a signatory to a number of regional and global agreements and conventions which are relevant in protection of wildlife including controlling wildlife crime. The regional conventions or agreements include Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement (1999), the Lusaka Agreement on Cooperative Enforcement Directed on Illegal Trade in Wild Fauna and Flora (Lusaka 1994) and the Master Plan for the Security of Rhino and Elephants in Southern Africa (1996). Tanzania is also a member of International Police Organization (INTERPOL) and signatory to the Convention of Biological Diversity (Rio de Janeiro 1992), African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (Algiers 1968) and the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Washington 1973).

Growing political commitment globally

The poaching surge, especially for iconic species, has prompted growing political commitments at the regional and global level as demonstrated by conferences held to deliberate on the need and strategies to fight the crime (Box 2) along with attention paid by the world leaders over the problem.

Measures adopted by prominent world leaders also demonstrate political commitment in fighting wildlife crime. For example, on July 1, 2013, the US President, Barack Obama, issued the Executive Order on Combating Wildlife Trafficking (The White House 2013), detailing different measures to be taken by his government to address the problem of wildlife crime. Obama pledged to provide financial and technical assistance to affected range States in order to tighten laws and increase capacity in combating wildlife trafficking. This Executive Order sends a very powerful message both domestically and internationally on the need to treat wildlife crime as a serious crime on a par with narcotics and arms trafficking.

In the same vein, ahead of the London Conference on the Illegal Wildlife Trade held in February, 2013, the Prince of Wales, Charles, and the Duke of Cambridge, William, launched an anti-poaching campaign with the video plea urging the world leaders to act promptly to stop illegal wildlife trade. In this video William warns that illegal trade “…poses a grave threat not only to the survival of some of the world’s most treasured species, but also to economic and political stability in many areas around the world” adding that “tomorrow will be too late to save endangered species.” (Reuters 2014).

Support from international organizations and agencies

Local efforts to fight wildlife crime are complemented by numerous international agencies and organizations. Examples of the organizations that have played a crucial role to this end include Worldwide Fund for nature (WWF), World Conservation Union (IUCN), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and African Wildlife Foundation (AWF). Notable support has also been realized from development agencies like USAID, NORAD, KfW and DfID, among others.

In November 2009, five international agencies with mandates in law enforcement and criminal justice capacity-building decided to come together to work jointly on the formation of an International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC). The agencies forming ICCWC include the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Secretariat, the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the World Bank and the World Customs Organization (WCO). ICCWC was the first initiative where these five agencies work together towards a common goal of delivering multi-agency support to affected countries.

Implications for conservation and development

Failure to address the challenges undermining the efforts geared towards combating wildlife crime has far reaching implications. One of the implications is failure of the country to comply with international commitments and obligations on fighting the crime. For example, according to WWF Report on compliance with and enforcement of CITES commitments for tigers, rhinos and elephants among the origin, transit and destination states, Tanzania had inadequate performance. It received yellow scores for both rhinos and elephants, indicating a broad need for improvement of enforcement, while other countries had green scores indicating adequate performance and red scores for very poor performance (Table 4).

Despite the challenges, opportunities for reversing the trend exist. Failure to take advantage of these opportunities to defeat the drivers and address the challenges exacerbating wildlife crime has far reaching implications to conservation. Figure 4 below summarizes these implications. If the current trend of poaching continues unabated the key wildlife species will be eliminated or reduced to the extent of affecting the country’s tourism industry, contributing substantially to GDP and creation of employment opportunities. This in turn, can reduce budget for conservation and lower the living standards among the staff and local communities. Inadequate budget causes inefficient law enforcement and may tempt the staff and communities to participate in wildlife crime in order to supplement their meagre income and meet their basic and development necessities. On the other hand, livelihood strategies may involve destruction of wildlife habitats through activities such as cultivation, deforestation and setting fires. Removal from ecosystem of the keystone and umbrella species due to poaching may equally affect the habitats causing further loss of species and disruption of ecological processes.

Besides economic and ecological implications, wildlife crime has been linked to security problems, particularly in Africa. Money generated from the crime is believed to finance terrorist activities and civil wars in a number of African countries. Unguaranteed security in countries affected by terrorism and civil wars undermines the tourism industry and open the door for more crimes including poaching. Civil wars produce refugees who flee their countries or areas to war-free areas. The influx and settling of refugees in new areas exert pressure on wildlife species and habitats as experienced in 1990s in the western Tanzania. Over 90 % of ungulate species became locally extinct in Burigi-Biharamulo Game Reserves and approximately 1000 km2 of land in BENACO Refugees Camp and the adjacent areas were affected by deforestation (Kideghesho and Msuya 2012).

Following increasing gravity of wildlife crime, Tanzania’s reputation has suffered as it has been implicated with scandals linking it with corruption and lack of accountability. Local and international media, conservation groups and politicians have indicted some senior government officials and politicians from the ruling party for this crime. For instance, while Fletcher (2014) accuses the government for inaction, EIA (2014) links the devastating poaching crisis in the country with increased criminality, corruption, the proliferation of firearms, the failure of the judicial system and the perception that Tanzania is a sanctuary for criminals.

Conclusion and recommendations

Wildlife crime remains a sad reality globally and, Tanzania is not exempted. Efforts to overcome this crime are hampered by a number of challenges including poverty, high profit associated with illicit trade on wildlife, corruption, inadequate institutional support, minimal benefits to local communities and human population growth. The ecological, economic, political and security implications of this crime are well acknowledged locally and globally. By taking advantage of the opportunities available the challenges undermining efforts to fight wildlife crime can be addressed. Given multiplicity of these challenges, however, multiple-strategies are required in defeating this crime. Among others, the following actions should be adopted:

-

Enhance collaboration with other stakeholders (such as civil society, private sector, local communities, governments and a wider UN system) to stop the killing, trafficking, and the demand for wildlife products.

-

Strengthen institutional, legal and regulatory systems to combat corruption, address wildlife-related offences effectively and ensure effective monitoring and management of the legal trade.

-

Improve morale among the wildlife employees. Among others, strategies to this end can include, educating the politicians to refrain from behaviours that dishearten the committed and loyal wildlife staff; acknowledging and recognizing efforts devoted by the staff despite difficulty and risk involved in their jobs, providing adequate working tools and staffing levels and ensure reasonable compensation through better salaries, hardship and risk allowances, and life insurances.

-

Improve the living standards of the people to preclude the scenario where wildlife crime is justified as a necessity on grounds of survival. This can be done by addressing the problem of unemployment, provision of fair compensation to civil servants and adopting poverty reduction strategies that are ecologically friendly.

-

Ensure adequate budget and other resources to enable effective law enforcement.

-

Ensure that political interests do not override the professionalism and do not discourage the committed and loyal employees from executing their duties.

-

Streamline the HIV-AIDS pandemic and climate change into conservation programmes and policies.

-

Enhance conservation education and awareness to general public on ecological, economic and social-cultural importance of wildlife species and, therefore, the impacts of wildlife crimes.

Notes

Tanzania has several strategies for poverty reduction such as BRN (big results now) and MKUKUTA (National Strategy for Poverty Reduction and Economic Growth).

References

Akarro RJ (2001) Population issues in refugges settlements of Western Tanzania. Tanzan J Popul Stud Dev 8(1&2):27–42

Baier EG (1997) The impact of HIV/AIDS on rural households/communities and the need for multisectoral prevention and mitigation strategies to combat the epidemic in rural areas. FAO, Rome

Baldus R, Kibonde B, Siege L (2003) Seeking conservation partnerships in the Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania. Parks 13(1):50–61

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Pol Econ 76:169–217

Bekerytė J (2013) Theoretical issues of relationship between unemployment, poverty and crime in sustainable development. J Sec Sustain Issues 2(3):59–70

Bitanyi S, Nesje M, Kusiluka LJM, Chenyambuga SW, Kaltenborn BP (2012) Awareness and perceptions of local people about wildlife hunting in western Serengeti communities. Trop Conserv Sci 5(2):208–224

Blevins KR, Edwards TD (2009) Wildlife crime. In: Miller JM (ed) 21st Century criminology. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 557–563

Block M, Heineke J (1975) A labour theoretical analysis of criminal choice. Am Econ Rev 65:314–325

CAG (Controller and Auditor General) (2011) Annual General Reports of the Controller and Auditor General on the Audits of the Financial Statements of the Central Government for the years ending 30th of June, 2010, 2011 & 2012. United Republic of Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

Campbell KLI, Hofer H (1995) People and wildlife: spatial dynamics and zones of interaction. In: Sinclair ARE, Arcese P (eds) Serengeti II: dynamics, management and conservation of an ecosystem. Chicago University Press, Chicago, pp 534–570

CEPF (Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund) (2005) Eastern Arc Mountains and Coastal Forests of Tanzania and Kenya Briefing Book. Improving Linkages between CEPFand World Bank Operations, Africa Forum, Cape Town, South Africa—April 25–27, 2005. 2005;http://www.cepf.net/Documents/final.easternarcmountains.briefingbook.pdf. Accessed on 10 Feb 2015

Christie IT, Fernandes E, Messerli H, Twining-Ward L (2014) Tourism in Africa: harnessing tourism for growth and improved livelihoods. African Development Forum, Washington DC

CITES (2013) Wildlife crime ranks among trafficking in drugs, arms and humans. http://cites.org/eng/news/sg/2013/20130926_wildlife_crime.php. Accessed on 15 July 2015

CIA World Factbook (2015) Population below poverty line (%) 2015 Country Ranks, By Rank. http://www.photius.com/rankings/2015/economy/population_below_poverty_line_2015_ Accessed on 15 July 2015

Cooper JE, Cooper ME, Budgen P (2009) Wildlife crime scene investigation: techniques, tools and technologies. Endanger Species Res 9:229–238

Cromsigt JPGM, te Beest M (2014) Restoration of a megaherbivore: landscape-level impacts of white rhinoceros in Kruger National Park, South Africa. J Ecol. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.12218

EAMCEF (2012) The Eastern Arc Mountains Conservation Endowment Fund. Resource Mobilization Strategy 2012–2016. EAMCEF, Morogoro, Tanzania

Ellis R (2005) Tiger bone & rhino horn: the destruction of wildlife for traditional Chinese medicine. Island Press, Washington

Emerton E, Mfunda IM (1999) Making wildlife economically viable for communities living around the Western Serengeti, Tanzania. IIED

Emslie R, Brooks M (1999) African rhino: Status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN, World Conservation Union, Cambridge

Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) (2014) Vanishing point: criminality, corruption and the devastation of Tanzania’s elephants. Environmental Investigation Agency, Washington DC. http://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/EIA-Vanishing-Point-lo-res1.pdf. Accessed on 10 July 2015

Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) (2015) European Union urged to ban ivory exports immediately. https://eia-international.org/european-union-urged-to-ban-ivory-exports. Accessed on 24 July 2015

EU (2015) Information on the EU ban on the import of elephant hunting trophies from Tanzania, Mozambique and Zambia. ec.europa.eu/environment/cites/pdf/elephanttrophies.pdf. Accessed on 24 July 2015

Fletcher M (2014) Tanzania slaughters over 11,000 elephants a year for the bloody trade in tusks and its President turns a blind eye, so will the Prince really shake hands with him? Daily Mail on Sunday, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2554773/Tanzania-slaughters-11000-elephants- Accessed on 9 July 2015

Forum Policy (2012) Revenue Losses owing to tax incentives in the mining sector: policy recommendations: policy brief 1:2012

Forum Policy (2013) Tanzania and the problem of tax exemption. Policy Brief 3:2013

Fyumagwa R, Gereta E, Hassan S, Kideghesho JR, Kohi EM, Magige F, Mfunda IM, Mwakatobe A, Ntalwila J, Nyahongo JW (2013) Road as a threat to the Serengeti ecosystem. Conserv Biol 27:1122–1125

Global Financial Integrity (2011) Transnational crime in the developing world. A Program of the Centre for International Policy, Washington DC

Global Financial Integrity (2012) Ivory and poaching. The global implications of poaching in Africa. A Program of the Centre for International Policy, Washington DC

Grozdanic A (2015) Burundian Refugees in Tanzania Predicted to Reach 250,000. http://www.savethechildren.org/site/apps/nlnet/content2.aspx Accessed on 9 July 2015

Holland H (2012) South Sudan’s elephants could be wiped out in 5 years. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/12/04/us-sudan-south-elephants-id Accessed on 9 July 2015

Holmern T, Roskaft E, Mbarukka J, Mkama S, Muya J (2002) Uneconomic game cropping in a community-based project outside the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Oryx 36(4):364–372

Holmern T, Muya J, Roskaft E (2007) Local law enforcement and illegal bushmeat hunting outside the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Environ Conserv 34:55–63

ITV (2016) British helicopter pilot ‘shot and killed’ by poachers in Africa. ITV Report, http://www.itv.com/news/2016-01-30/british-helicopter-pilot-shot-and-killed/. Accessed on 31 Jan 2016

Jambiya G, Milledge S, Mtango N (2007) Night time spinach: conservation and livelihood implications of wild meat use in refugee situations in north-western Tanzania. TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa

Kalron N (2012) Africa’s white gold of jihad: al-Shabaab and conflict ivory. Elephant League. [Online] http://elephantleague.org/project/africas-white-gold-of-jihad-al-shabaab-and-conflict-ivory/. Accessed on 9 July 2015

Kelly M (2000) Inequality and crime. Rev Econ Stat 82:530–539

KEP (1997) Impact assessment study in refugee affected districts of Biharamulo, Ngara and Karagwe. Draf Report. Kagera Environmental Report. Tanzania Agro-industrial Services Limited, Dar es Salaam Tanzania

Kideghesho JR (2015) Realities on deforestation in Tanzania—trends, drivers, implications and the way forward. In: Miodrag Z (ed) Precious Forests—precious Earth. Intech Open Science/Open Minds, Rijeka, pp 21–47

Kideghesho JR (2016) Elephant poaching crisis in Tanzania: A need to reverse the trend and the way forward. Trop Conserv Science 9(1):377–396

Kideghesho JR, Msuya TS (2012) Managing the wildlife protected areas in the face of global economic recession, HIV/AIDS pandemic, political instability and climate change: experience of Tanzania. In: Sladonja B (ed.) Protected Areas Management. INTECH Open Science/Open minds, pp 65–91. ISBN: 980-953-307-448-6

Kideghesho JR, Roskaft E, Kalternborn BJ, Tarimo TMC (2005) Serengeti not die: can the ambition be sustained? Intern J Biodiv Sci Manag 1(3):150–166

Kideghesho JR, Nyahongo JW, Hassan SN, Tarimo TC, Mbije EN (2006) Factors and ecological impacts of wildlife habitat destruction in the Serengeti Ecosystem in Northern Tanzania. Afr J Environ Assess Manag 11:17–32

Knapp EJ (2012) Why poaching pays? a summary of risks and benefits illegal hunters face in Western Serengeti, Tanzania. Trop Conserv Sci 5(4):434–445

Laing A (2015) Tanzania’s elephant catastrophe: ‘We recalculated about 1,000 times because we didn’t believe what we were seeing.’ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/tanzania/11748349/. Accessed on 27 Jan 2016

Leader-Williams N, Albon SD, Berry PSM (1990) Illegal exploitation of black rhinoceros and elephant populations: patterns of decline, law enforcement and patrol effort in Luangwa Valley, Zambia. J Appl Ecol 27(3):1055–1087

Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC) (2014) Operation Tokomeza Ujangili Report. LHRC, Dar es Salaam Tanzania

Loibooki M, Hofer H, Campbell KLI, East M (2002) Bushmeat hunting by communities adjacent to Serengeti National Park: the importance of livestock ownership and alternative sources of protein and income. Environ Conserv 29:391–398

Marais A, Fennessy S, Fennessy J (2012) Giraffe conservation status—Country Profile: Democratic Republic of Congo. Giraffa 6(2):13–16

Martin A, Caro T, Borgerhoff Mulder M (2012) Bushmeat consumption in western Tanzania: a comparative analysis from the same ecosystem. Trop Conserv Sci 5(3):352–364. www.tropicalconservationscience.org

Masilingi WMK (1994) Socio-economic problems experienced in environmental compliance and enforcement in Tanzania. Fourth Int Conf Int Compliance 2:63–73

Metzger KL, Sinclair ARE, Hilborn R, Grant J, Hopcraft C, Mduma SAR (2010) Evaluating the protection of wildlife in parks: the case of African buffalo in Serengeti. Biodivers Conserv 19:3431–3444

Mfunda IM, Roskaft E (2010) Bushmeat hunting in Serengeti, Tanzania: an important economic activity to local people. Intern J Biodivers Conserv 2:263–272

Mouquet N, Gravel D, Massol F, Calcagno V (2013) Extending the concept of keystone species to communities and ecosystems. Ecol Lett 16(1):1–8

Muller Z (2008) Quantifying giraffe poaching as population threat. The Rothschild’s Giraffe Project. www.girafferesearch.com/…/Quantifying giraffe poaching as a population threat. Accessed on January 14, 2016

NBS (1988) Tanzania = population census. National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

NBS (2002) Tanzania—2002 Population and Housing Census. National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

NBS (2011) Tanzania in figures. National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

NBS (2012) 2012 Population and husing census. National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

NBS (2013) The 2011/12 National Household Budget Survey. The National Bureau of Statistics, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania

NBS (2015) Tanzania in figures. National Bureau of Statistics, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Ndibalema VG, Songorwa AN (2007) Illegal meat hunting in Serengeti: dynamics in consumption and preferences. Afr J Ecol 46:311–319

Nellemann C, Henriksen R, Raxter P, Ash N, Mrema E (eds.) (2014) The environmental crime crisis—threats to sustainable development from illegal exploitation and trade in wildlife and forest resources. A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment. United Nations Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal, Nairobiand Arendal, http://www.unep.org/unea/docs/RRAcrimecrisis.pdf

Nowell K (2012) Wildlife crime scorecard: assessing compliance with and enforcement of CITES commitments for tigers, rhinos and elephants. WWF Report. http://www.legalservicesindia.com/article/article/is-poverty-a-cause-of-corruption-1613-1.html. Accessed on 10 July 2015

Ripple WJ, Newsome TM, Wolf C, Dirzo R et al. (2015). Collapse of the world’s largest herbivores. Sci Adv, May 2015. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400103. Accessed on 10 July 2015

Roberge JM, Angelstam P (2004) Usefulness of the umbrella species concept as a conservation tool. Conserv Biol 18:76–85

Rugalema G (1999) It is not only the loss of labour: HIV/AIDS, loss of household assets and household livelihood in Bukoba District, Tanzania. In: Mutangadura G, Jackson H, Mukurazita D (eds) AIDS and African Smallholder Agriculture. Southern African AIDS Information Dissemination Service (SAFAIDS), Harare

Saah RJ (2012) Janjaweed and ivory poaching: Cameroon calls in the army to combat wave of elephant poaching in national park. Reuters. http://africajournalismtheworld.com/tag/janjaweed-and-ivory-poaching/. Accessed on 10 July 2015

Schiffman R (2014) Ivory poaching funds most wars and terrorism in Africa. Environment. http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg22229692.700-ivory-poaching-funds-most-war-and-terrorism-in-africa.html#. Accessed on 10 July 2015

Šileika A, Smith RJ, Walpole MJ (2005) Should conservationists pay more attention to corruption? Oryx 39:251–256

Smith RJ, Muir RDJ, Walpole MJ, Balmford A, Leader-Williams N (2003) Governance and the loss of biodiversity. Nature 426:67–70

Somaville K (2014) Ivory, insurgency and crime in central Africa: the Sudans connection. http://africajournalismtheworld.com/tag/janjaweed-ivory/. Accessed on 10 July 2015

Songorwa AN (2015) Sustaining wildlife conservation in growing socio-economic demands: Can the elephant in Tanzania survive the current wave of poaching? The 10th TAWIRI Biennial Scientific Conference December 2–5, 2015 Arusha, Tanzania

Strauss M (2015) Who Buys Ivory? You’d be surprised. A new international survey reveals what’s really driving the demand side of the ivory market. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/08/150812-elephant-ivory-demand-wildlife-trafficking-china-world/. Accessed on 20 Jan 2016

The Ecologist (2015) Tanzania in denial over 60 elephant population crash. http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_round_up/2896170/ Accessed on 9 July 2015

The White House (2013) Executive Order—Combating Wildlife Trafficking. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/01/executive-order-combating-wildlife-trafficking. Accessed on 5 July 2015

Times Arusha (2004) A difficult year for wildlife. Arusha, Times 499

TRAFFIC (2012) Illegal hunting and trade of wildlife in savanna Africa may cause conservation crisis. ScienceDaily, 12 October 2012

Transparency International (2011) Corruption Perceptions Index. Transparency International. https://www.transparency.org/cpi2011. Accessed on 10 July 2015

Transparency International (2015) Corruption by Country/Territory. http://www.transparency.org/country#TZA. 10 July 2015

Tumanjong E (2012) Foreign poachers target Cameroon elephants: expert. The World Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/huff-wires/20121204/af-cameroon-elephant-poaching/ Accessed on 12 July 2015

UN (2014) Security Council, Adopting Resolution 2195 (2014), Urges International Action to Break Links between Terrorists, Transnational Organized Crime. http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11717.doc.htm. Accessed on 10 July 2015

UNDESAPD (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division) (2012) World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. (Medium variant). Population pyramid of the world from 1950 to 2100. http://populationpyramid.net/united-republic-of-tanzania/2025/. Accessed on 7 July 2015

UNEP-WCMC (2004) World Conservation Monitoring Centre of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP-WCMC), 2004. Known Species of Mammals, Plants, and Breeding Birds (unpublished, September 2004). UNEPWCMC, Cambridge. http://www.unep-wcmc.org. Accessed on 5 July 2015

UNESCO (2014) Poaching puts Tanzania’s Selous Game Reserve on List of World Heritage in Danger. http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1150/. Accessed on 20 Dec 2015

UNHCR (2015) Burundian Refugees in Tanzania—Daily Statistics. For more information on the Burundi situation. http://data.unhcr.org/burundi/country.php. Accessed on 10 July 2015

UNODC (2015) Wildlife crime worth USD 8-10 billion annually, ranking it alongside human trafficking, arms and drug dealing in terms of profits: UNODC chief. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2014/May/wildlife-crime-worth-8-10-billion-annually.html. Accessed on 10 July 2015

URT (2007) The wildlife policy of Tanzania. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

URT (2013) Report by the Parliamentary Select Committee for Lands. Natural Resources and Environment on Operation Tokomeza Ujangili, Dar es Salaam Tanzania

URT (2015) Migration and Urbanization Report. Population and Housing Census 2012. National Bureau of Statistics, p 68

URT(United Republic of Tanzania) (2013) Speech by the Minister for Finance William Mgimwa during the 2013/14 Budget Speech whilst introducing to the National Assembly, the Estimates of Government Revenue and Expenditure for the Fiscal Year 2013/2014. Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, Tanzania

USAID (1999) A handbook on fighting corruption. Technical Publication Series, PN-ACE-070, Washington, DC: USAID Center for Democracy and Governance

US Embassy (2012) Protection of Cameroon’s Wildlife a National Security Priority. Press Release by US Ambassador, Michael S. Hoza. http://yaounde.usembassy.gov/pr_030315.html. Accessed on 8 July 2015

US-FWS (2014) Import of Elephant Trophies from Tanzania and Zimbabwe. US Fish and Wildlife Service—International Affairs. http://www.fws.gov/international/permits/by-activity/sport-hunted-trophies.html. Accessed on 30 June 2015

Vira V, Ewing T (2014) Ivory’s Curse—The Militarization and Professionalization of Poaching in Africa. Born Free USA, Washington D. C. April, p 104

Whiteside A (2002) Poverty and HIV/AIDS in Africa. Third World Q 23(2):313–332

Wildlife Division (WD) (2013a) Wildlife sub-Sector Statistical Bulletin 2013 Second Edition, Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Wildlife Division (WD) (2013b) Status of Poaching in Tanzania. A Paper Submitted to the President’s Office. The United Republic of Tanzania

Wildlife Sector Review Task Force (WSRTF) (1995) A Review of the Wildlife Sector in Tanzania. Volume 1: Assessment of the Current Situation. Dar es Salaam: Ministry of Tourism, Natural Resources and Environment, Tanzania

World Bank (2014) GDP per Capita. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY Accessed on 18 June 2015

World Bank (2015) Working for a World Free of Poverty. Tanzania Overview. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/tanzania/overview. Accessed on 18 June 2015

World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) (2013) Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2013 Sub Saharan Africa. WTTC, London

WWF (2012) African troops to fight Sudanese elephant poachers. Sudan tribune. http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article45980. Accessed on 28 May 2015

Zhao H, Feng Z. Castillo-Chavez C (2002) The dynamics of poverty and crime. Preprint MTBI-02-08 M 9, 2002

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Karen E. Hodges.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kideghesho, J.R. Reversing the trend of wildlife crime in Tanzania: challenges and opportunities. Biodivers Conserv 25, 427–449 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1069-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1069-y