Abstract

The endemic large carpenter bee, Xylocopa darwini Cockerell, was the only known pollinator to the Galápagos Archipelago but as early as 1964 locals also spoke of the “dwarf bee of Floreana”. We report the presence of the wool carder bee, Anthidium vigintiduopunctatum Friese, on the island of Floreana and use a species distribution model to predict its distribution in the archipelago. We found that this species has the potential to invade almost one-third the surface area of the Galápagos Archipelago, primarily in low arid areas. Given that wool carder bees are uncommonly collected, we discuss whether this species is a previously undetected native bee or a recent adventive species to the Galápagos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Depauperate bee faunas are the norm for oceanic islands (Michener 1979), even for those with large land masses where they are distant from mainlands. The Galápagos Archipelago is no exception. Its bee fauna has been thought to be limited to a sole pollinator, the endemic carpenter bee Xylocopa darwini Cockerell 1926 (Apidae, Xylocopini). But a hint of a possible second bee pollinator exists. During fieldwork on pollinators of the Galápagos in 1964, locals spoke of the “dwarf bee of Floreana”, but researchers did not encounter it (Linsley et al. 1966). In this paper, we report the presence of the wool carder bee, Anthidium vigintiduopunctatum Friese 1904, on Floreana, one of the three islands with a high number of introduced insect species (Peck et al. 1998). We also use a species distribution model (SDM) to predict the potential distribution of this bee in the archipelago.

The Galápagos Archipelago of Ecuador comprises 127 volcanic islands located about 1,000 km west from the nearest continental land-mass; only 19 of these islands are over 1 km2. The climate is arid to semi-arid at low elevations but wetter at high elevation and on their windward sides (Peck 2001 and references therein). Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, Floreana, and Baltra are, in descending order of population, the inhabited islands of the archipelago (Causton et al. 2006). To date, a total of 463 introduced species of insects (137 families in 16 orders) have been recorded for the Galápagos Archipelago (Causton et al. 2006).

Species of Anthidium Fabricius are commonly known as wool carder bees because their cotton-like brood cells are made of plant fibers (Grigarick and Stange 1968). These solitary bees nest in pre-existing cavities in the soil, walls, wood, stems, etc. (Michener 2007) or may excavate shallow burrows in loose, friable soils (T.G., personal observation). Anthidium contains nearly 200 species worldwide, more frequently found in xeric climates of temperate areas than in tropical humid forests. The native range of A. vigintiduopunctatum includes Ecuador and Peru, but there is an unconfirmed record from Mendoza, Argentina (Urban 2002). In the U. S. National Pollinating Insects Collection, Logan, UT, USA (US-NPIC), we found three specimens of A. vigintiduopunctatum that were collected between March and April of 1996 in two different ecosystems on Floreana, Galápagos Islands: humid forest (Scalesia) and arid zone forest (see Examined material below). Causton et al. (2006) also recorded an unidentified species of Anthidium from Santa Cruz collected in 2002. We were unable to study this material to determine its identity.

It is possible that A. vigintiduopunctatum is a previously undetected native of the Galápagos Archipelago. Wool carder bees are uncommonly collected, in part because they are swift and wary bees, difficult to capture. Standard sweeping techniques, often used for general insect surveys, are unlikely to capture them. Further, these bees appear to be uncommon elements of bee faunas, with often localized distributions, especially in the tropics. For example, in four systematically sampled multiyear faunal studies in North America (T.G., unpublished data), all in different ecosystems, Anthidium accounted for just a tiny fraction of bees collected (\( \overline{x} \) = 0.63%, range = 0.55–0.78%, n = 204,803 specimens).

Alternatively, the presence of A. vigintiduopunctatum may represent a recent colonization of the Galápagos. Wood and stem cavity nesters predominate among adventive bees. Two Old World species, A. manicatum (Linnaeus, 1758) and A. oblongatum (Illiger, 1806), are adventive to the New World. The former species was first recorded from New York in 1963 and has now been established in eastern and western United States; it has also become established in southern Brazil, Peru, Suriname, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, New Zealand, and the Canary Archipelago (Gibbs and Sheffield 2009 and unpublished records from www.discoverlife.org); the latter species is established in the upper Midwest and northeastern North America (Miller et al. 2002 and unpublished records from www.discoverlife.org). If the adventive hypothesis is correct, and the 2002 record of Anthidium (Causton et al. 2006) is A. vigintiduopunctatum, it might indicate an expanding range from Floreana to other islands or it might represent an independent, more recent introduction from the continental mainland.

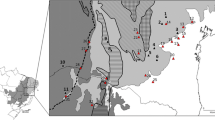

Adventive species may fail to become established if suitable habitats or adequate resources are not available. To predict the potential distribution of A. vigintiduopunctatum on the archipelago of Galápagos, we constructed a SDM. Recent studies have applied SDM to predict the potential distribution of adventive bee species (e.g., Hinojosa-Díaz et al. 2005). We compiled four unique locality records for A. vigintiduopunctatum based on museum specimens deposited at the US-NPIC and literature; missing geographical coordinates in locality records were georeferenced using Google Earth (www.earth.google.com). Records from Floreana were not included because we wanted to determine habitat suitability of Galápagos based on the species’ habitat on the South American continent. We applied maximum entropy, using MaxEnt (version 3.06) (Phillips et al. 2006) with default parameters, to estimate the potential geographic distribution. Even at small sample sizes like ours, MaxEnt can discriminate between suitable and unsuitable habitats (e.g., Wisz et al. 2008). We used 19 bioclimatic variables as predictors at a spatial resolution of 1 km2 (Hijmans et al. 2005). All variables were clipped to the South American continent and the Galápagos Archipelago. Bioclimatic values were associated with each occurrence record on the South American continent and then reflected onto the Galápagos Archipelago using 4000 randomly distributed points. Results from the SDM were processed and visualized using ArcGIS 9.2 (ESRI 2006).

From the SDM generated, we found that about 2,080 km2 of the Galápagos Archipelago has a habitat suitability value greater than 0.50; however, the total area of habitat suitability increased 23% when the two localities from Floreana were included in the model. The habitats most suitable for A. vigintiduopunctatum are the arid low areas of the archipelago. Although the known occurrence records of A. vigintiduopunctatum are from Floreana, the highest probability of occurrence (>0.75) based on habitat suitability is on the island of San Salvador (Santiago) and the northernmost region of Santa Cruz; lower values (~0.50) were found on Isabela and Floreana. These results suggest that A. vigintiduopunctatum has the potential to invade almost one-third the surface area of the Galápagos Archipelago.

Island ecosystems are vulnerable to invasions due to disharmonic biota (Carlquist 1965) and simplified food webs (Pimm 1991). The threats of introduced and invasive species on island ecosystems have been documented in several plant-pollinator assemblages (Cox and Elmqvist 2000 and references therein); however, the impact of non-native pollinator species has yet to be thoroughly investigated on the Galápagos Archipelago. A recent study by Philipp et al. (2006) on pollination networks in the Galápagos Archipelago did not detect A. vigintiduopunctatum on lava desert habitats on Isabela. Whether this wool carder bee is adventive or not, further surveys are necessary to determine its current distribution in the Galápagos Archipelago.

Examined material

ECUADOR. Galap: 1♀ Floreana, Cerro Paja base; FIT [Flight intercept trap] 16-22.iv.1996; 300 m. Scalesia forest. S. Peck 96–120. K.W. Cooper Collection USDA Logan, Utah. KWC0011884; idem, 2♂, Finca Cruz; malaise, 130 m; arid zone forest 27.iii-16.iv.1996. KWC0011883, KWC0011882.

References

Carlquist S (1965) Island life. Natural History Press, Garden City, New York

Causton CE, Peck SB, Sinclair BJ, Roque-Albelo L, Hodgson CJ, Landry B (2006) Alien insects: threats and implications for conservation of Galápagos islands. Ann Entomol Soc Am 99:121–143

Cox PA, Elmqvist T (2000) Pollinator extinction in the Pacific islands. Conserv Biol 14:1237–1239

ESRI (2006) ArcGIS 9.2. ESRI, Redlands, California

Gibbs J, Sheffield CS (2009) Rapid range expansion of the wool-carder bee, Anthidium manicatum (Linnaeus) (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), in North America. J Kans Entomol Soc 82:21–29

Grigarick AA, Stange LA (1968) The pollen-collecting bees of the Anthidiini of California. Bull Calif Insect Survey 9:1–113

Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A (2005) Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 25:1965–1978. Available at www.worldclim.org

Hinojosa-Díaz IA, Yáñez-Ordóñez O, Chen G, Peterson AT, Engel MS (2005) The North American invasion of the giant resin bee (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae). J Hymen Res 14:69–77

Linsley EG, Rick CM, Stephens SG (1966) Observations on the floral relationships of the Galápagos carpenter bee. Pan-Pac Entomol 42:1–18

Michener CD (1979) Biogeography of the bees. Ann Mo Bot Gard 66:277–347

Michener CD (2007) The bees of the world, 2nd edn. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Miller SR, Gaebel R, Mitchell RJ, Arduser M (2002) Occurrence of the two species of old world bees, Anthidium manicatum and A. oblongatum (Apoidea: Megachilidae), in northern Ohio and southern Michigan. Gt Lakes Entomol 35:65–70

Peck SB (2001) Smaller orders of insects of the Galápagos islands, Ecuador: evolution, ecology and diversity. NRC Research Press, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Peck SB, Heraty J, Landry B, Sinclair BJ (1998) Introduced insect fauna of an oceanic Archipelago: the Galápagos islands, Ecuador. Am Entomol 44:218–237

Philipp M, Böcher J, Siegishmund HR, Nielsen LR (2006) Structure of a plant-pollinator network on a pahoehoe lava desert of the Galápagos islands. Ecography 29:531–540

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE (2006) Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distribution. Ecol Model 190:231–259

Pimm SL (1991) The balance of nature: ecological issues in the conservation of species and communities. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Urban D (2002) O gênero Anthidium Fabricius na América do Sul: chave para as espécies, notas descritivas e de distribuição geográfica (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae, Anthidiini). Rev Bras Entomol 46:495–513

Wisz MS, Hijmans RJ, Li J, Peterson AT, Gram CH, Guisan A, NCEAS Predicting Species Distributions Working Group (2008) Effects of simple size on the performance of species distribution models. Divers Distrib 14:763–773

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Joe Wilson, Molly Rightmyer, Claus Rasmussen and an anonymous reviewer for their comments and suggestions that improved this note. This study was supported in part by National Science Foundation grant DEB-0742998.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gonzalez, V.H., Koch, J.B. & Griswold, T. Anthidium vigintiduopunctatum Friese (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae): the elusive “dwarf bee” of the Galápagos Archipelago?. Biol Invasions 12, 2381–2383 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-009-9651-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-009-9651-9