Abstract

Oriental weatherfish has become an invasive fish species in many temperate areas. In this work we report the presence of an established weatherfish population in northeastern Iberian Peninsula and describe, for the first time in Europe, a clear range expansion. The species was first located in the Ebro River Delta in 2001 and has since been detected in 31 UTM 1 × 1 km quadrates. The capture of over 1,000 weatherfish shows that its population is composed by both juvenile and adult individuals. Weatherfish occupies mostly the web of irrigation channels associated with rice culture, although it has also been detected in rice fields and in the Ebro River. The expansion of the species in the area seems to be limited by water conductivity. An additional location for the species in the Ter basin (some 300 km to the north) suggests that inter-basin expansion could be occurring. This new fish invasion reinforces the need to implement strict controls to the trade and culture of ornamental fish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The spread of non-native invasive species is one of the main global threats to biodiversity and a leading cause of animal extinctions (Vitousek et al. 1997; Clavero and García-Berthou 2005) also producing important social and economic impacts (e.g. Pimentel et al. 2000). Freshwater ecosystems have been shown to be especially sensitive to non-native species invasions, which have led many freshwater fish species to range reductions, population declines and even extinction (Cowx 2002; Smith and Darwall 2006). The introduction of non-native fish species is an ongoing process in many European areas (e.g. Bianco and Ketmaier 2001; Clavero and García-Berthou 2006). Some of these liberated species are expected to become established (up to 60% after García-Berthou et al. 2005) and a sub-group among them could then proliferate and expand their ranges, becoming truly invasive species (Copp et al. 2005).

The oriental weatherfish (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus, henceforth weatherfish) is a cobitid species with a wide native range in Eastern Asia, from Burma to Siberia, including the Japanese archipelago (Tabor et al. 2001; Froese and Pauly 2007). Mainly due to its frequent use as ornamental fish, but also as food source and live bait, weatherfish has become an invasive species in different places throughout the world (Froese and Pauly 2007). The species was introduced to Hawaii during the 19th century and to continental USA (where it is still expanding) and Philippines in early 20th century. More recently it has cited as established in Australia and Turkmenistan (Freyhof and Korte 2005).

In Europe, two different weatherfish populations have been reported to have established in the wild, one from northern Italy (Razzetti et al. 2001) and another from Germany (Freyhof and Korte 2005). These populations are located in isolated ponds (Kottelat and Freyhof 2007), and range expansions have not yet been described. Ribeiro et al. (2008) cited the presence of weatherfish in the Iberian Peninsula, although they classified it as a “failed introduction”. However, this statement was not supported by field data and was based on a few weatherfish individuals captured in the Ebro River Delta and sent by JMQ and NF to the authors. The aim of this study is to report the presence of well established weatherfish population in the Ebro River Delta (NE Iberian Peninsula) and describe its rapid short-term geographical expansion.

Study area and methods

The Ebro River Delta is a large (32,000 Ha) alluvial plain formed in a West–East direction by the deposition of sediments as the river enters the Mediterranean Sea. The Delta is divided by the river in two sectors, the northern and southern hemideltas. The Ebro Delta Natural Park (EDNP) protects some 7,730 Ha, mostly comprising lagoons, marshes and coastal ecosystems. More than 60% of the delta surface is nowadays covered by rice fields, which are irrigated by a complex web of channels involving a water flow of 45–50 m3/s. Both inflow (taking water to the rice fields) and outflow (taking water from them) channels are dried once every year (between January and February) for maintenance operations. Fish rescues are then performed by the EDNP, during which fish remaining in the channels are captured and native species are liberated in the river. Most data on weatherfish distribution from 2001 to 2006 come from these fish rescues. However, weatherfish has been also captured with fyke nets by the EDNP personnel while performing monitoring surveys.

Between June and October 2007 105 locations within the Delta were sampled using fyke nets to better characterise weatherfish distribution and habitat. Fyke nets were set in groups of three and left for 24 h. Sampled habitats were classified in five groups: inflow channels, rice fields, outflow channels, lagoons and marshes. Weatherfish densities were expressed as CPUE (captured individuals/trap × day) and CPUE values were log10(X + 1) transformed prior to analyses. Possible differences in weatherfish densities across habitats were analysed through one-way ANOVA.

The identification of captured weatherfish individuals was made using the key provided by Kottelat and Freyhof (2007).

Results and discussion

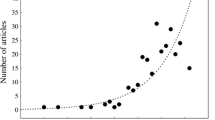

Weatherfish was first detected in the northern hemidelta in 2001 by a local fisherman, who captured the species in a fyke net. Since then, it has expanded its range to occupy most of this hemidelta and colonize the southern one, where it was first detected in 2005 (Fig. 1). Up to the present the species has been detected in 31 1 × 1 km UTM squares. This increasing geographic spread is coupled with a growing number of individuals captured during fish rescues and monitoring surveys and of reports of captures by local fishermen.

Top left: map of the Iberian Peninsula showing the location of the Ebro Delta (marked by the square) and the Bugantó stream (Ter basin, filled circle). The other maps show the geographical expansion of the oriental weatherfish (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) in the Ebro Delta since its first location in 2001. The grid shows 1 × 1 km UTM quadrates

The size distribution of captured weatherfish (Fig. 2) show that the population is composed both by adult and juvenile individuals, although the latter were not captured during the fish rescues, due to the small size, criptic coloration and benthic habits, and are possibly underestimated by fyke nets captures (see Clavero et al. 2006). The power function relating fish weight (W, in grams) and total length (TL, in mm) for individuals captured during fish rescues (during winter) was W = 0.0039 × TL3.0722 (n = 331; R 2 = 0.95; P < 0.001).

Size frequency distribution of weatherfish captured with fyke nets (open bars) and during fish rescues (filled bars). Intervals are 10 mm. Note that fyke nets surveys were performed in summer and early autumn, while fish rescues took place during winter, possibly explaining the displacement between the two data sets

Between 2001 and 2007 weatherfish has been captured in both in inflow and outflow channels, with either concrete or silt substrates, as well as in rice fields and in the Ebro River. The 2007 survey showed that weatherfish densities were highest in inflow channels (1.15 ind./trap × day) and outflow channels (1.10 ind./trap × day). The species was scarce in rice fields (0.19 ind./trap × day) and it was not located in marshes or lagoons. These differences were statistically significant (F 4,100 = 2.58; P = 0.04). To the date, the species has not been shown to colonize lentic habitats in the Delta, probably due to the high salinity of most lagoons and marshes within the area. In fact, in the 2007 survey weatherfish was never captured when water conductivity was over 3 mS/cm (Fig. 3).

Although there is not a direct evidence on the mechanism involved in the introduction of the weatherfish in the Ebro Delta, the presence of an ornamental fish farm in the surroundings of the place where the species was first detected clearly points towards an escape from this facility. The same origin was proposed for the introduction of topmouth gudgeon (Pseudorasbora parva) in the Ebro Delta (Caiola and Sostoa 2002), which was first recorded in 1999 in the same channel where weatherfish was later localised in 2001 (Queral 2002). Topmouth gudgeon is nowadays one of the most abundant fish species in the Ebro Delta and is expanding its range to other Iberian basins (Pou-Rovira et al. 2007). Moreover, different exotic fish species, such as the ide (Leuciscus idus), suckermouth catfishes (Plecostomus sp.) or piranhas (Serrasalmus sp.), have been detected in the same area, although they do not seem to have become established (Queral 2001; Franch and Queral 2005). These facts clearly reinforce the need to implement strict controls to the trade and culture of ornamental fish, which is nowadays considered a major vector of freshwater fish introductions (e.g. Courtenay 1999; Padilla and Williams 2004).

There is very little available information on weatherfish impacts on native biota in those areas where the species has become invasive. In fact, no negative impacts on native fish have been reported in the USA (Logan et al. 1996) or Europe (Freyhof and Korte 2005). However, Dove and Ernst (1998) showed the role of weatherfish on the establishment of an exotic monogean fish parasite in Australia, while Tabor et al. (2001) suggested that the species could compete with native fish, predate on fish eggs or cause unpredictable indirect effects following ecosystems modifications. In the Ebro River Delta and, in general in Iberian fluvial systems, it can be argued that an expansion of weatherfish could have negative effects on the populations of benthic, invertebrate-feeder fishes, such us Cobitis and Barbatula loaches or the freshwater blenny (Salaria fluviatilis). Both Cobitis paludica and freshwater blenny are scarce and seriously threatened species in the Ebro River Delta, as well as in the whole Iberian Peninsula (Doadrio 2002).

On the other hand, on May 2007 a juvenile weatherfish individual (65 mm TL) was captured in the Bugantó Stream, a tributary of the Ter River (see Fig. 1), during a fish survey using fyke nets (Pou-Rovira et al. 2007). Although the species cannot be yet classified as established in this new area, it is interesting to note that weatherfish seems to be following an expansion pattern (from the Ebro to other NE Iberian basins) that has been previously recorded for other species, such as the wels catfish (Silurus glanis) (Doadrio 2002; Benejam et al. 2007) and the topmouth gudgeon (Caiola and Sostoa 2002; Pou-Rovira et al. 2007).

The data reported in this work show that weatherfish is not only well established in the Ebro Delta, but that it is also becoming a truly invasive species (following Copp et al. 2005). It has been able to expand its range to occupy relatively wide range of aquatic habitats, including both natural and disturbed ones. The recent record of the species outside the Ebro basin could also show a wider-scale spread, similar to those performed by other invasive species recently introduced to the Iberian Peninsula (e.g. Clavero and García-Berthou 2006; Vinyoles et al. 2007).

References

Benejam L, Benito J, Carol J, García-Berthou E (2007) On the spread of the European catfish (Silurus glanis) in the Iberian Peninsula: first record in the Llobregat river basin. Limnetica 26:169–171

Bianco PG, Ketmaier V (2001) Anthropogenic changes in the freshwater fish fauna of Italy, with reference to the central region and Barbus graellsii, a newly established alien species of Iberian origin. J Fish Biol 59(Suppl. A):190–208

Caiola N, de Sosota A (2002) First record of the Asiatic cyprinid Pseudorasbora parva in the Iberian Peninsula. J Fish Biol 61:1058–1060

Clavero M, García-Berthou E (2005) Invasive species are a leading cause of animal extinctions. Trends Ecol Evol 20:110

Clavero M, García-Berthou E (2006) Homogenization dynamics and introduction routes of invasive freshwater fish in the Iberian Peninsula. Ecol Appl 16:2313–2324

Clavero M, Blanco-Garrido F, Prenda J (2006) Monitoring small fish populations in streams: a comparison of four passive methods. Fish Res 78:243–251

Copp GH, Bianco PG, Bogutskaya N et al (2005) To be, or not to be, a non-native freshwater fish? J Appl Ichthyol 21:242–262

Courtenay WR Jr (1999) Aquariums and water gardens as vectors of introduction. In: Claudi R, Leach JH (eds) Nonindigenous freshwater organisms: vectors, biology, and impacts. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton

Cowx IG (2002) Analysis of threats to freshwater fish conservation: past and present challenges. In: Collares-Pereira MJ, Cowx IG, Coelho MM (eds) Conservation of freshwater fishes: options for the future. Fishing News Books, Blackwell Science, Oxford

Doadrio I (ed) (2002) Atlas y libro rojo de los peces continentales de España (Atlas and red book of Spanish freshwater fishes). Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Madrid (in Spanish)

Dove ADM, Ernst I (1998) Concurrent invaders—four exotic species of Monogenea now established on exotic freshwater fishes in Australia. Int J Parasitol 28:1755–1764

Franch N, Queral JM (2005) Informe sobre les introduccions d’espècies forànies al Delta (Report on non-native species introduccions in the Delta). Ero Delta Natural Parc. Technical report (in Catalan)

Freyhof J, Korte E (2005) The first record of Misgurnus anguillicaudatus in Germany. J Fish Biol 66:568–571

Froese R, Pauly D (2007) FishBase. http://www.fishbase.org (version 08/2007)

García-Berthou E, Alcaraz C, Pou-Rovira Q et al (2005) Introduction pathways and establishment rates of invasive aquatic species in Europe. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 65:453–463

Kottelat M, Freyhof J (2007) Handbook of European freshwater fishes. Publications Kottelat, Cornol, Switzerland

Logan DJ, Bibles EL, Markle DF (1996) Recent collections of exotic aquarium fishes in the freshwaters of Oregon and thermal tolerance of oriental weatherfish and pirapatinga. Calif Fish Game 82:66–80

Padilla DK, Williams SL (2004) Beyond ballast water: aquarium and ornamental trades as sources of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Front Ecol Environ 2:131–138

Pimentel D, Lach L, Zuniga R, Morrison D (2000) Environmental and economic costs of nonindigenous species in the United States. BioScience 50:53–65

Pou-Rovira Q, Clavero M, Zamora L (2007) Els peixos de les Gavarres i entorns (Fishes of the Gavarres mountains and its sorroundings). Biblioteca Lluís Esteva, vol 5. Consorci de les Gavarres, Monells, Girona, Spain (in Catalan)

Queral JM (2001) Llistat actualitzat de les espècies de peixos del Delta (Revised checklist of fish species in the Delta). Soldó 17:12 (in Catalan)

Queral JM (2002) Nova espècie de peix a les aigües deltaiques (A new fish species in the Delta). Soldó 18:3 (in Catalan)

Razzetti E, Nardi PA, Strosselli S, Bernini F (2001) Prima segnalazione di Misgurnus anguillicaudatus (Cantor, 1842) in acque interne italiane (First citation of Misgurnus anguillicaudatus in Italian freshwaters). Ann Mus Civ Stor Nat Genova 93:559–563 (in Italian)

Ribeiro F, Elvira B, Collares-Pereira MJ, Moyle PB (2008) Life-history traits of non-native fishes in Iberian watersheds across several invasion stages: a first approach. Biol Invasions 10:89–102

Smith KG, Darwall WRT (compilers) (2006) The status and distribution of freshwater fish endemic to the Mediterranean Basin. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland

Tabor RA, Warner E, Hager S (2001) An oriental weatherfish (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) population established in Washington state. Northwest Sci 75:72–76

Vinyoles D, Robalo JI, de Sostoa A et al (2007) Spread of the alien bleak Alburnus alburnus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Actinopterygii, Cyprinidae) in the Iberian Peninsula: the role of reservoirs. Graellsia 63:101–110

Vitousek PM, Mooney HA, Lubchenco J, Melillo JM (1997) Human domination of Earth’s ecosystems. Science 277:494–499

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the kind help given by Dr. J. Freyhof for weatherfish identification.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Franch, N., Clavero, M., Garrido, M. et al. On the establishment and range expansion of oriental weatherfish (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) in NE Iberian Peninsula. Biol Invasions 10, 1327–1331 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-007-9207-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-007-9207-9