Abstract

For decades, scholars and public health officials have been concerned with the depictions of sexual aggression in pornography, especially when acts of aggression are depicted with no consequences. Social cognitive theory suggests behaviors that are rewarded are more likely to be learned by consumers while those punished are less likely to be learned. To date, however, there has not been a large-scale content analysis to provide researchers with the baseline knowledge of the amount of sexual aggression in online pornography nor have previous content analyses examined the reactions of the targets of sexual aggression. This study of 4009 heterosexual scenes from two major free pornographic tube sites (Pornhub and Xvideos) sought to provide this baseline. Overall, 45% of Pornhub scenes included at least one act of physical aggression, while 35% of scenes from Xvideos contained aggression. Spanking, gagging, slapping, hair pulling, and choking were the five most common forms of physical aggression. Women were the target of the aggression in 97% of the scenes, and their response to aggression was either neutral or positive and rarely negative. Men were the perpetrators of aggression against women in 76% of scenes. Finally, examining the 10 most populous categories, the Amateur and Teen categories in Xvideos and the Amateur category in Pornhub had significantly less aggression, while the Xvideos Hardcore category had significantly more physical aggression against women. This study suggests aggression is common against women in online pornography, while repercussions to this aggression are rarely portrayed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For decades, scholars, cultural critics, governments, and public health officials have been concerned about the effect of pornography on sexual aggression (Bronstein, 2011). Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, feminists like Dworkin (1981) and MacKinnon (1984) sought to ban pornography on the basis that pornography’s depiction of sexual aggression was a sexual discrimination of women and a civil rights violation and should therefore be illegal. At the same time, the U.S. government through the Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography’s (1986) declared that pornography was linked to an increase in sexual aggression and sexual assault. Despite the strong opposition, pornography creation and consumption have continued. While some suggest mainstream culture has become increasingly pornified (Paasonen, Nikunen, & Saarenmaa, 2007; Paul, 2007), other scholars suggest access to pornography may prevent sexual crimes (Diamond, Jozifkova, & Weiss, 2011). Additionally, some scholars remained skeptical of a direct and powerful effect of pornography, suggesting that the level of violent content and the individual differences of consumers moderated the effect on consumer’s sexually aggressive attitudes and behaviors (Check & Malamuth, 1986; Donnerstein, 1984; Ferguson & Hartley, 2009; Linz, 1989; Linz, Penrod, & Donnerstein, 1987). Over the next four decades, societal concern over the effect of pornography on sexual aggression and sexual assault has sparked international conversation and remains a pressing and controversial question today.

While the controversy has continued over the years, one new and expansive form of media has changed the way the world thinks about pornography: the Internet. For example, one of the most popular pornographic websites, Pornhub.com, reported 42 billion visits worldwide in 2019 and averaged 115 million visits per day (Pornhub Insights, 2019). Scholars are still attempting to identify and understand the qualities of online pornography, given that different types of pornography may impact different attitudes and behaviors. Within the literature, there is a lack of research on the diversity of depictions of sexual aggression within pornography. Although smaller studies have examined a few hundred DVDs or video clips, there is no “big data” content analysis of sexual aggression from a large, diverse online sample of pornography (Bridges, Wosnitzer, Scharrer, Sun, & Liberman, 2010; Fritz & Paul, 2017; Gorman, Monk-Turner, & Fish, 2010; Klaassen & Peter, 2015; Monk-Turner & Purcell, 1999). Given the past 40 years of debate about the effects and role of sexual aggression in media, researchers need a large-scale examination of online pornography to understand how sexual aggression is depicted, what type of aggression is depicted, who are the targets and perpetrators, what are their reactions, and how does the depiction of aggression vary by category.

Literature Review

Pornography as Sex Education: The Effect of Pornography on Sexual Aggression

Social cognitive theory suggests that people may learn behaviors through either direct experience or through observation, including through media. Furthermore, media consumers learn which behaviors are acceptable based on whether the depictions of these actions are rewarded or punished (Bandura, 2001). Specifically focusing on sexual media, the acquisition, activation, and application model (3AM) of sexual socialization has explored how media depictions of sexual content may affect consumers (Wright, 2011). In addition to rewarded behaviors being better acquired, and activated, the model specifically notes that the depictions of behaviors in sexual media such as pornography can normalize these scripts, making them more likely to be utilized (i.e., applied). For pornography consumers, the depictions of pleasurable and sexually aggressive sex without consequences may lead to a salient sexual socialization learning experience. Scholars have found evidence of a positive relationship between pornography consumption and various aggressive behaviors. For example, Wright, Sun, Steffen, and Tokunaga (2015) found, in a sample of heterosexual German men, that more frequent consumption of pornography was associated with desiring and having engaged in physically aggressive behaviors (such as hair pulling) and verbally aggressive behaviors (such as name calling). A meta-analysis of 22 studies indicated that consumption of pornography was associated with sexually aggressive behaviors (Wright, Tokunaga, & Kraus, 2016). Interestingly, the difference in the strength of the effect of violent versus nonviolent pornography on behaviors was not statistically significant in this meta-analysis of behaviors. Notably, one study did find consumption of violent pornography increased the relationship between pornography consumption and sexually aggressive attitudes more than nonviolent content (Hald, Malamuth, & Yuen, 2010). Using the confluence model of sexual aggression, some scholars suggest that depictions of aggression in pornography may only impact sexually aggressive men who are already at high risk to commit sexual assault or that only content with high levels of violence affect consumers (Baer, Kohut, & Fisher, 2015; Malamuth, 2018). Although there is still debate about the degree of the influence of pornography, evidence thus far suggests there is an effect, although more research is needed is clearly needed.

Researchers have also explored the impact of pornography consumption on potentially harmful sexually aggressive attitudes. Hald, Malamuth, and Lange (2013) found that men’s pornography consumption was related to higher levels of hostile sexism toward women. A meta-analysis of non-experimental studies also found that consumption of pornography is associated with more accepting attitudes of violence against women (Hald et al., 2010). Furthermore, a study conducted by Wright and Tokunaga (2016) suggests pornography consumption is associated with higher levels of acceptance of violence against women, though these attitudes were mediated by men’s beliefs of women as sex objects. Taken together, the evidence thus far suggests a positive relationship between pornography consumption and both aggressive behaviors and attitudes.

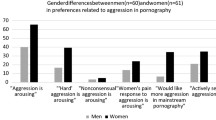

The evidence also suggests pornography consumption similarly affects female consumers of pornography. A recent meta-analysis found that gender did not moderate the relationship between pornography consumption and sexually aggressive behaviors, suggesting women also acquire and apply sexually aggressive scripts (Wright et al., 2016). Additionally, Peter and Valkenburg (2007) found an association between pornography consumption and viewing women as objects prevalent among young men and women. This suggests that pornography may also affect women’s views of other women as well as of themselves as sex objects. This cognitive change may lead to women accepting sexual aggression against themselves as well as engaging in sexually aggressive behaviors against other women.

The concern over the impact of pornography on viewers’ sexually aggressive behaviors is heightened because of the lack of quality sex education and focus on abstinence only education in the U.S. (Lerner & Hawkins, 2016; Lindberg, Maddow-Zimet, & Boonstra, 2016). Researchers suggest some adolescents may be using the Internet as their primary source of sexual health information, including using pornography as a teaching tool (Rothman, Kaczmarsky, Burke, Jansen, & Baughman, 2015). Pornhub even recently launched its own separate sexual education site dedicated to safe sex and answering young people’s sexual questions. Other research, however, suggests that adolescents are not using only the Internet for sexual health information and are aware the Internet is not a reliable source of sexual health information (Jones & Biddlecom, 2011). While adolescents may not want to get their sexual health information from the Internet, they may have few other sources. Without the assistance of interventions, parents are often ill-equipped to give adequate sexual information to their children (Ballonoff Suleiman, Lin, & Constantine, 2016; Evans, Davis, Ashley, & Khan, 2012; Fisher et al., 2009). Mainstream mass media such as TV, music, and magazines rarely contain any helpful sexual health messages (Aubrey & Frisby, 2011; Dillman Carpentier, Stevens, Wu, & Seely, 2017; Hust, Brown, & L’Engle, 2008). Even if adolescents are not purposefully going to the Internet seeking sexual health information, they may still learn and utilize the sexual behaviors and attitudes depicted in pornography, especially in the absence of other healthy sexual messages in society. Some researchers also suggest, even more than adolescents, adults may be impacted by the risky sexual scripts in pornography (Peter & Valkenburg, 2011). Pornography literacy programs have begun to be explored as a potential tool to help diminish the effects of pornography use. A recently completed longitudinal study found that sexual education that includes porn literacy decreases the negative effect of pornography use on attitudes that objectify women (Vandenbosch & van Oosten, 2017). Research suggests that while people may not want to get their sexual health information from pornography, many consumers may still be learning sexual scripts and harmful sexual scripts (including those involving aggression) from pornography.

Sexual Aggression in Online Pornography: What We Know and What We Want to Know

A recent study suggests, despite being researched for decades, pornography as a concept is still culturally relative, with no clear, universally accepted definition (McKee, Byron, Litsou, & Ingham, 2020). Similarly, there are substantial differences in the literature between the examination of sexual violence and sexual aggression in pornography. Sexual violence has been defined as harmful acts in which the perpetrator intended to cause pain and the target attempted to avoid the act (Gorman et al., 2010; McKee, 2005). Other researchers define sexual aggression as physical acts that cause harm regardless of the intent of the perpetrator. For example, in a content analysis by Barron and Kimmel (2000), coders were provided with a list of physically aggressive acts to code regardless of intent, such as pushing, pulling hair, biting, and “being rough in an otherwise ‘normal’ activity” (p. 164). Other researchers also suggest that the intent of the perpetrator to cause harm is not necessary to make an act aggressive. Bridges et al. (2010) aptly pointed out that it is nearly impossible to code intent, and if researchers only coded what appear to be intentional acts of aggression, this may render “aggressive acts as invisible when they occur within the context of sex” (p. 1067). It appears there is a conceptual difference between sexual violence and sexual aggression in the research. Considering social learning theory, however, it is important to code what is visible to the consumer and not interpret the potential intent. Various theories of social learning suggest individuals learn based on what they see. If there is no explicit indication of consent or intent, consumers may perceive that sexual aggression without verbal consent is not only acceptable, but a normative and expected component within sex. In the current study, physical aggression is therefore defined as any action that clearly does or could reasonably be expected to cause physical harm to oneself or another person, regardless of the perpetrator’s intent and the target’s response. Notably, few researchers have defined or investigated verbal aggression in pornography. Previous researchers have included name calling or insulting as an act of verbal aggression (Bridges et al., 2010; Gorman et al., 2010). Similar to physical aggression, verbal aggression is any action that does or could reasonably be expected to cause psychological harm to oneself or another person, whereby harm is understood as resulting from verbal assault.

Establishing a Baseline

Some of the earliest research comparing pornographic online videos to VHS and magazines found notable contrasts. Research by Barron and Kimmel (2000), examining 50 sexual stories from Usenet, 50 pornographic VHS videos, and 50 pornographic magazines found that 42% of scenes in online pornography contained acts of sexual violence, which was significantly higher than in VHS (27%) or magazines (25%). Recently, a few small content analyses have explored sexual violence in pornography with mixed findings. McKee (2005) found only 1.6% of scenes from 50 DVDs analyzed contained sexual violence. Notably, McKee narrowly defined violence strictly as nonconsensual behaviors where the target attempts to avoid or get away from the perpetrator. Similarly, Gorman et al. (2010) examined 45 online videos and found that overt physical violence was rare and occurred in only one video, while gagging or coercive sex was found in only 5 of the 45 videos. Using a broader definition of aggression that did not define aggression based on perpetrator intent, Bridges et al. (2010) found much higher levels of aggression in 50 of the bestselling pornographic DVDs. Their study found 88.2% of scenes contained physical aggression, which was coded regardless of perpetrator intent, and ranged from spanking, to gagging, to hair pulling. Another recent analysis of 400 online videos found 37.2% of scenes contained physical aggression against women (Klaassen & Peter, 2015). Fritz and Paul (2017) found 31% of a small sample of mainstream online videos (N = 100) contained depictions of physical aggression. Similarly, Shor and Golriz (2019) found that 43% of scenes in a sample of 206 Pornhub online videos contained visible physical aggression.

Findings from the sparse number of studies measuring verbal aggression in pornography have yielded varying results. Barron and Kimmel (2000) found 15% of a sample of written sexually explicit stories found on the Internet included verbal aggression. Gorman et al. (2010) found 3 out of 45 online videos contained name calling. Bridges et al. (2010) found much higher levels of verbal aggression with 49% of DVD scenes containing verbal aggression, with insulting being the most common form of verbal aggression. Given the prevalence of online pornographic videos and the discrepancy between studies in terms of the prevalence of both physical and verbal aggression, researchers need a baseline for understanding the level of sexual aggression now available in online pornography, as well as a sense of what types of sexual aggression are being depicted. For the purpose of this study, both physical and verbal sexual aggression are examined and compared.

Research Question 1(a) (b): What proportion of scenes contain at least one act of (a) physical aggression and (b) verbal aggression?

Research Question 1(c): What is the prevalence of specific types of physical aggression across scenes?

The Targets of Aggression and Their Responses

Previous content analyses find that women are overwhelmingly the target of aggression in pornography. Barron and Kimmel (2000) found that women, more often than men, were depicted as victims of the sexual violence in all three media they analyzed, including online pornography (84.7%), VHS movies (79.6%), and in magazines (61.5%). Bridges et al. (2010) found women were the targets of 94% of aggressive acts depicted in their sample of 50 DVDs. Two recent studies utilizing samples of online pornography also found women were more often depicted as the target of sexual aggression: 37% of scenes in Klaassen and Peter (2015) content analysis contained sexual aggression against women and 36% of scenes in Fritz and Paul’s (2017) study, compared to 3% and 1% of scenes containing aggression against men, respectively. Taken together, previous content analyses of pornography find women are far more often the target of aggression than men. Most models of social learning suggest consistency and frequency of messages matter. If women are more often the target of aggression, the consistency of this message will make it more likely to be learned. Additionally, social cognitive theory suggests that the depicted reaction to behavior in media is important. Positive reactions by the target of a behavior are understood as reinforcing or rewarding the behavior, while negative reactions may discourage viewers from applying such behaviors. If women react either positively or neutrally to aggression, sexually aggressive scripts held by the consumers may be reinforced. Given the framework of learning theory, we pose the following questions:

Research Question 2: In what proportion of coded acts of aggression are women the (a) target and/or (b) the perpetrator compared to men?

Research Question 3: In what proportion of coded acts of aggression, do women have a negative reaction when they are the target of sexual aggression?

Type of Pornography

Mainstream pornography is defined as different from feminist or niche pornography because of its focus on pleasing a mass audience and bringing in a profit (Fritz & Paul, 2017). There are many different categories or genres of content within mainstream pornography, however. Recent content analyses have highlighted the importance of examining how different categories of pornography vary in their depiction of sexual scripts. Klaassen and Peter (2015), for example, compared pornography categorized as professional or amateur and found women were the target of aggression in professional content significantly more than in amateur content. Another content analysis examined 100 online videos, comparing videos from the Teen category to videos from the MILF (Mother I’d Like to Fuck) category, and found that women in the MILF and Teen category were spanked equally (Vannier, Currie, & O’Sullivan, 2014). Given recent research into the differences between categories, it is worthwhile to consider whether the most populous pornographic categories present depictions of sexual aggression differently.

Research Question 4: Are there differences in the depiction of physical aggression across the Teen, MILF/Mature, Amateur, and Hardcore categories within Xvideos and Pornhub?

Method

A large-scale content analysis coded a sample of 7430 pornographic videos taken from two free Internet pornographic tube sites, Xvideos.com and Pornhub.com, which are two of the most popular sites according to alexa.com and similarweb.com. The study was designed to find rare units of analysis (.001 probability) that were significantly different at .01. Using Krippendorff’s (2004) sample size guide, the total number of videos needed was 4603 (p. 12). This study oversampled and also added additional LGBT videos after the initial video collection, raising the total number to 7430. The goal of this large-scale project was to take a snapshot of popular online pornography by sampling a large and random number of videos from each site. Videos were not selected based on posted date or popularity. Instead a random sample of all available videos was taken to demonstrate what sexual behaviors a selected video of Internet pornography might contain.

Measures and Procedure

Sampling

This study examined the heterosexual subset of the total sample, including 4009 heterosexual scenes from 3767 videos sampled from Pornhub.com (574 scenes) and Xvideos.com (3435 scenes). Data for this analysis came from two separate groups of coders trained using the same coding book. The first large group of coders coded a sample of videos from, Xvideos; the second, smaller group coded a smaller selection from Pornhub in order to add diversity to the sample and also for comparison purposes. For this analysis, only videos classified as heterosexual by Pornhub and Xvideos were analyzed; notably some heterosexual videos included same-sex sexual behaviors and aggression; however, these data are not analyzed in this study. Additionally, only videos that included at least two people were included; scenes classified as “solo” with only one performer were not included in the analysis. The sampling unit for this study was an online video. Videos from the sites sometimes contained multiple scenes within the video. Thus, while the sampling unit was a video, the unit of analysis and coding unit was a scene.Footnote 1 Additionally, within each scene, all acts of aggression were coded as separate events. For example, a man spanking a woman was coded as one act of aggression until he stopped the action. If the woman then slapped the man, this was coded as a separate act of aggression. Based on this approach, 4453 separate acts of aggression were coded across all sampled videos. All videos were randomly selected from Fall 2013 through Spring 2014. Random selection was done by one researcher who recorded all selections for student coders. A systematic random sample was obtained, wherein the total number of pages within a category was divided by the total number of videos desired for that category to obtain the sampling interval. The first video on the first page in the interval was chosen, followed by the second video on the second page in the interval, the third video on the third page in the interval, and so on. After the final video on a page was chosen, the process of picking specific videos would start over, and the first video on the next page in the interval would be used. This process was applied to the given category until the desired number of video clips was obtained. The desired number of videos was determined by finding the ratio of the number of videos in that category compared to the total number of videos on the site and then applying that ratio to the total number of videos selected for the sample. Videos that were compilations, animated, or over 1-h long were excluded from the sample and the next video on the page was selected.

Coding

Coding was conducted by 33 trained undergraduate students. There were two groups of student coders; one who coded videos from xvidoes.com, consisting of 27 students, and another who coded videos from pornhub.com, consisting of 6 students. Each student trained for 20 h to learn the coding scheme and to obtain acceptable levels of coding reliability. To assess intercoder reliability, each coder applied the codebook to 20 non-randomly selected videos. Reliability was evaluated using percentage agreement among coders on each individual indicator. Potter and Levine-Donnerstein (1999) suggested percentage agreement can be used over other statistical approaches for accessing reliability because with a high number of coders, agreement by chance was low and that reliability tests like Krippendorff’s alpha penalize one coder’s disagreement when coding bivariate indicators. Similar studies utilizing a large number of coders have also used percentage agreement (e.g., Malik & Wojdynski, 2014; Zhou & Paul, 2016). Separate reliabilities were calculated for the groups that coded content from Xvideos.com and Pornhub.com, because members of these two groups coded different sets of reliability videos. Overall, the Xvideos coding group reached 97.6% agreement in physical aggression and 88.9% agreement in verbal aggression. The Pornhub coding group reached 97.9% agreement in physical aggression and 97.5% agreement for verbal aggression. A complete list of aggression codes and reliabilities are shown in Table 1. After training, coders were assigned 10–20 videos a week for individual coding.

Physical Aggression

Physical aggression was coded as any action that clearly did or could reasonably be expected to cause physical harm to oneself or another person, regardless of the perpetrator’s intent and the target’s response. Borrowing from Barron and Kimmel (2000), coders coded acts of physical aggression including pushing, gagging, hair pulling, spanking, punching, slapping, choking, use of a weapon, mutilating, and other. Spanking was defined as striking on the buttocks with an open hand to differentiate spanking from open-handing slapping, which was defined as striking oneself or another with an entirely unclosed hand, group of fingers, or palm not on the buttocks. Utilizing the coding schema of Bridges et al. (2010), the target of the act of physical aggression was coded as male or female. The perpetrator was coded as male, female, or self. The reaction was coded as positive (i.e., smiling or verbally approving), neutral (no reaction), or negative (i.e., frowning or telling a person to stop.)

Verbal Aggression

Verbal aggression was coded as any action that clearly did or could reasonably be expected to cause psychological harm to oneself or another person, regardless of the perpetrator’s intent and the target’s response. As in Gorman et al. (2010) and Bridges et al. (2010), verbal aggression included name calling or insulting, including those that discriminate by gender such as “slut” or “bitch.” Target, perpetrator, and response to verbal aggression were coded the same as they were for physical aggression.

Results

Frequencies and percentages of the scene-level and act-level variables of interest including type, target, and perpetrator of aggression as well as the reaction to the aggression were examined. Pearson’s Chi-square was used to compare the frequency of depicted aggression between Pornhub and Xvideos and between the coded categories. Given the number of Chi-squared analyses, the criterion significance level was reduced to .01 to correct for false discovery.

Site Comparison

It is necessary to note the statistically significant differences in level of aggression between the two samples sites. Overall, Pornhub had significantly more scenes containing at least one act of physical aggression against a man or a woman (45.1%) than Xvideos (35.0% of scenes), χ2(1, 4009) = 22.97, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .08. Looking specifically at target of aggression, 44.3% of Pornhub scenes and 33.9% of Xvideos scenes contained physical aggression against women, while 3.7% of Pornhub scenes and 2.5% of Xvideos scenes contained aggressive acts against men, which was not statistically different. Like different categories within a streaming site, Pornhub and Xvideos may be qualitatively different.

Common Types of Sexual Aggression and Target

The first research question asked what proportion of scenes contain physical or verbal aggression. Examining Pornhub, 45.1% of scenes contained at least one act of physical aggression, while in the Xvideos sample, 35.0% of scenes contained at least one act of physical aggression. Verbal aggression was far less common in scenes on both sites, with 10.1% of Pornhub scenes containing at least one coded act, compared to 10.0% of Xvideos scenes.

The three most commonly depicted types of physical aggression on both sites were spanking (Pornhub, 32.1%; Xvideos, 23.8%), slapping (Pornhub, 12.2%; Xvideos, 6.8%), and gagging (Pornhub, 11.7%; Xvideos, 6.5%). Pornhub contained significantly more scenes that depicted the top three types of aggression, including spanking, χ2(1, 4009) = 17.96, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .07, slapping χ2(1, 4009) = 19.39, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .07, and gagging, χ2(1, 4009) = 20.06, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .07. Additionally, bondage, χ2(1, 4009) = 9.12, p < .01, Cramer’s V = .05, and weapon use, χ2(1, 4009) = 14.13, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .06, were depicted significantly more in Pornhub scenes (bondage: 3.3%, weapon use: 2.1%) than Xvideos scenes (bondage: 1.5%, weapon use: 0.6%). Table 2 provides all frequencies and percentages for each coded form of aggression separated by the gender of target and by site.

Target, Perpetrator, and Reaction to Aggression

The second research question considered who the target and perpetrator of sexual aggression was. To answer this question, this analysis examined the most common forms of sexual aggression, including insulting, spanking, slapping, gagging, pulling hair, and choking, resulting in a total of 574 and 3435 separate acts of physical or verbal aggression in Pornhub and Xvideos, respectively. Overall, women were the target of aggression in 96.7% of physically aggressive acts in the Pornhub sample and 96.8% in the Xvideos sample. Men were the aggressors against women in 75.9% of all acts of physical aggression in Pornhub and 76% of all acts of physical aggression in Xvideos. Women were the aggressors against other women in 13.8% of Pornhub acts of physical aggression and 12.1% of Xvideos acts of physical aggression. Women were the aggressors against themselves in 7% of all physical acts of aggression in the Pornhub sample and 8.8% of Xvideos acts. Men were the target of physical aggression in 3.3% of all physical acts of aggression in the Pornhub sample and 3.2% in the Xvideos sample. Women were the perpetrators of violence against men in just 2.8% of acts in the Pornhub sample, while men were aggressive against themselves or other men in only .6% of acts. In the Xvideos sample, women were the perpetrators of violence against men in 3.1% of acts, while men were aggressive against themselves or other men in .04% of acts. Complete breakdowns of the top six most frequent types of aggression depicted from both sites can be found in Tables 3 and 4.

In answer to the third research question, women were found to respond to physically aggressive acts with either pleasure or neutrally in 97.4% physical acts of aggression appearing on Pornhub, and 92.7% of scenes containing aggression on Xvideos. Women expressed displeasure in response to just 2.3% of physically aggressive acts depicted on Pornhub, compared to 7.3% of those on Xvideos. Women responded with pleasure or neutrality in response to 98.7% of Pornhub verbal acts of aggression compared to 90.5% of Xvideos verbal acts of aggression. For a complete analysis of women’s responses to the top five physical acts of aggression, see Table 5.

Varying Depiction by Category

The final research question asked if there was a difference in the amount of aggression between different categories. Categories were separated by streaming site and were then compared to all other videos in the sample from the site excluding the category of interest. Content in the Pornhub’s Amateur category had significantly less aggression compared to the average across the categories, χ2(1, 574) = 5.99, p < .01, Cramer’s V = .01 (19% less). Within Pornhub, the categories of Teen, Mature, and Hardcore did not vary significantly in the level of depicted physical aggression against women. Examining Xvideos, content categorized as Amateur depicted 18% less aggression than the average across all other categories, χ2(1, 3435) = 8.68, p < .01, Cramer’s V = .002, while content categorized as Hardcore, χ2(1, 3435) = 16.35, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .004, depicted 22% more aggression. Differences between the Teen category and all others on Xvideos also approached significance, depicting 5% less aggression, χ2(1, 3435) = 4.39, p = .04, Cramer’s V = .001. The MILF category was not significantly different. See Table 6 for a complete list of differences and corresponding percentage differences.

Discussion

A Baseline of Sexual Aggression in Online Pornography

The current study provides a baseline of the prevalence of sexual aggression on two popular online pornography sites based on a large-scale content analysis. Previous studies of sexual violence or aggression in pornography have varied widely in their reported presence of aggression, ranging from as few as 1.6% of examined scenes in a non-random sample of 50 popular DVDs (McKee, 2005) to as high as 88% in a non-random sample of 100 popular pornographic DVDs (Bridges et al., 2010). The current study found physical aggression against women present in 44.3% of Pornhub and 33.9% of Xvideos scenes. These findings are in line with the findings from the studies by Klaassen and Peter (2015) and Shor and Golriz (2019) of online videos. Given that Bridges et al. (2010) examined pornographic DVDs, it may be that longer, professionally made videos contain more aggression. Indeed, Klaassen and Peter (2015) found that “professional” online videos contained more physical aggression against women than videos labeled as “amateur.” Furthermore, often videos on free pornographic tube sites such as Pornhub and Xvideos are shorter video clips of longer pornographic scenes. It may be that some aggression is cut out of the clips in editing for the free tube sites.

There are notable differences in how content was coded between this study and the work of McKee (2005) and others. The lower observed acts of aggression in certain previous content analyses may be the result of their use of a stricter definition for aggression. Indeed, both Gorman et al. (2010) and McKee (2005), who found low levels of observed aggression in their samples, used the term “violence” instead of “aggression.” Their conceptualizations of violence were narrower and included only more extreme acts that depicted perpetrator’s intent to harm and the target attempting to stop the violence. There is still not a clear consensus in the academic community nor in society in general about what constitutes sexual aggression compared to sexual violence. More research is needed to examine the potential effects of pornographic depictions of intended sexual violence compared to ambiguous aggression.

Verbal Versus Physical Aggression

The current study found that physical aggression was substantially more common in online pornographic videos than verbal aggression. Although this study did not record the content of every insult, many insults were gender-specific, such as calling a woman a “bitch” or “slut.” This finding may also reflect the relatively low level of verbal communication in pornography, especially on free streaming sites. Many videos are edited to cut out many of the early action and scenes. These scenes are typically the ones providing context for the subsequently depicted sexual action and are also likely to include dialogue which may include verbal aggression.

Overall, physical aggression was present in more than a third of pornographic videos in the sample. Spanking was found to be the most common type of physical aggression, occurring in almost a third of Pornhub scenes and in almost a quarter of Xvideos scenes. Although some critics have suggested spanking and gagging may not qualify as a particularly “rough” or intense form of aggression, it has certainly become an accepted and increasingly significant part of the normal sexual script in pornography (Gorman et al., 2010; McKee, 2005). Notably, gagging often occurs not with fellatio, but with forceful fellatio, during which a man holds his partner’s head in place while thrusting his penis in and out. The gagging that is produced with forceful fellatio implies at least that the man’s partner is uncomfortable, and that air flow may be interrupted. Therefore, it seems like gagging, which occurred in 6.7% of the scenes, could be considered a physically aggressive act worth future investigation. Notably, more extreme aggression such as mutilating, kicking, punching, or using a weapon occurred relatively infrequently across the videos in the sample. While “extreme” types of aggression were rare, the greater prevalence of milder versions of aggression such as spanking suggests to viewers that such acts are normative without explicit verbal consent as part of sexual behavior.

The Complicated Relationship between Aggressor and Target

In line with results from previous studies, women were overwhelmingly found to be the target of both physical and verbal aggression (Bridges et al., 2010; Klaassen & Peter, 2015). Specifically, women were the target of nearly 97% of all physically aggressive acts in the samples from both sites. This is an important finding. Although some have argued spanking could be considered a non-aggressive sexual act if the intent is not to harm (McKee, 2005), the data suggest women are the target of spanking in almost all scenes. Our data clearly suggest that a sexual script of spanking women but not spanking men is being normalized within online pornography. Indeed, all examined aggressive acts appear normalized to be perpetrated toward women and not men, such that it is implausible to imagine a woman spanking a man, choking him, or pulling his hair outside the context of a consensual BDSM depiction. As such, most physical aggression has not just been normalized in the sexual script, and it has been normalized to be against women.

Aggression Against Self

Although women were overall the primary target of aggression, a more complicated relationship was evident when examining who was the perpetrator of aggression against women. Although men still primarily demonstrated physical aggression against women (about three quarters of all acts), women aggressed other against other women or themselves in about 20% of all physically aggressive acts. Often self-aggressive behaviors begin pornographic scenes; the actress will strip for the camera, spanking her buttocks or slapping her breasts. Considered through the framework of Fredrickson and Roberts’ (1997) objectification theory, this suggests it is not just that men who are objectifying women, but that women are self-objectifying. The script of aggression against women has become so normalized that women hit and spank themselves, partaking in the sexual script of aggression against women. It should also be noted there were almost no acts of men aggressing against themselves or other men.

Positive and Apathetic Reactions to Aggression

The findings indicate women’s response to both physical and verbal aggression is overwhelmingly positive or neutral, demonstrating either explicit or implicit affirmations of pleasure. This is not to say women cannot enjoy acts of aggression, particularly when it is consensual. However, it is problematic if women respond to aggression appetitively, or by displaying no reaction at all. Affirmative reactions endorse a sexual script suggesting women enjoy and welcome aggression, while neutral reactions suggest a woman is not even engaged with the sexual aggression against her. She has become a sexual object with no interaction with her sexual partner. If the only responses seen when women are the target of aggression are pleasure or non-response, male viewers may assume women either enjoy aggression or that their feelings or feedback regarding aggression is simply not important. This may normalize a script of a woman’s body as an object or recipient of aggression. Women may also learn that they are supposed to experience pleasure with aggression or that they should ignore any discomfort they do experience and give a neutral response. This general lack of displeasure by women in response to seemingly unpleasant occurrences in pornography implies they should enjoy all sexual behaviors enacted upon them.

This finding also has implications for the definition of sexual aggression and sexual violence. For example, McKee (2005) conceptualized violence as acts “which were obviously not consensual and therefore included an element of desire to harm” (p. 283). McKee further explained that he separated and defined “isolated moments of rough play” as those where a character may experience violence, but “makes it clear in another way that he is enjoying this” (p. 283). While this conceptualization limits and defines the concept clearly, it also depends heavily on the observed reactions of the participants and the interpretation of the consumer. Using this definition, most of the coded aggression would not be considered violence, since the targets do not react with clear displeasure. This argument about what defines of violence in pornography puts the onus on the target to say yes to violence instead of the perpetrator to gain consent, however. Based on such a definition, if a woman does not say no or act with displeasure to a potential act of aggression, then the act must be defined as consensual and is not violence. This type of argument reconstructs the incorrect assumption that a “lack of no” is the same as consent.

Finally, this “lack of a no” conceptualization of sexual violence ignores the way in which women are socialized to respond to unwanted touching, attention, or harassment with smiles to not further escalate the aggression. It assumes that all unwanted or harmful aggression can safely be met with an agentic and purposeful “no” statement. Research in a variety of fields suggests women respond neutrally to and/or avoid confrontation with sexual harassment in the military (Bell, Turchik, & Karpenko, 2014), in the nursing industry (Cogin & Fish, 2009), in migrant farm fields (Waugh, 2010), and within video game culture (Fox & Tang, 2017). Indeed, research even shows that in hypothetical scenarios, women believe that a victim who reports harassment in the workplace will receive negative feedback from her colleagues (del Carmen Herrera, Herrera, & Expósito, 2017). Women’s lack of negative response in pornography to the majority of sexual aggression they receive is another way in which women are socialized to not escalate aggression.

Differences Between Categories

Consistent with Klaassen and Peter (2015), the current analysis found videos categorized in the Amateur category depicted significantly less aggression than those in other categories. It should be noted, however, that there has been an industry shift in the past few years toward the production of “pro am” content, or professional amateur pornography. This is content produced using professional performers, directors, ad crews while delivering more of an amateur aesthetic. It is unknown if such content depicts more or less aggression than traditional professional videos. Categories signaling “professional” content such as “Hardcore” on Xvideos were found to contain more aggression. Interestingly though, the Pornhub Hardcore category did not contain more aggression, suggesting category title might not be the best indicator of level of aggression. It also may be that overall, Pornhub contains more aggression, or that aggression on that site has become normalized across categories. Given the focus on how level of aggression in pornography may moderate the effect on sexually violent behaviors, more research is needed on the differences of depictions across categories of pornographic content.

Future Use of Porn

This study suggests that a significant portion of pornography contains depictions of aggression against women with no negative responses from targets; this may lead to the development among consumers of a sexual script that encourages the learning of aggression against women. Although consumers may not go to mass media, including pornography, with the specific motivation to learn sexual behaviors, they still might absorb the provided scripts. Research suggests mass media, ranging from magazines, to TV, to pornography, can have an impact on consumers’ sexual attitudes and behaviors (Hust et al., 2013; Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2015; Wright et al., 2016). But, what if pornography was created with the intent to increase consumers’ attitudes toward consent or toward mutually pleasurable sex? What if pornography included communication during sex, with actors verbalizing consent with each other? If pornography included scripts of enjoyable sex with verbalized consent, it could possibly be utilized as a supplemental tool supporting sexual education instead of as a source of misinformation and unhealthy sexual scripts.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the current findings. First, these results are restricted by the population pool from which they were sampled. Although Pornhub.com and Xvideos.com are two of the most popular free adult tube sites, it is unknown if other types of pornographic sites, such as paid sites, niche sites, or alt porn sites, contain substantially different contents. As the amount and variety of pornographic content online grow, this limitation will be a continuing question for researchers. Additionally, this study did not attempt to measure audience reactions to the content, or individuals’ ability to opt out of consuming aggressive pornography. The study attempted to create a baseline for understanding the nature of sexual aggression depicted on the pornographic tube sites examined, but it does not speak to how viewers may interact with or feel about this content. Finally, these findings cannot speak to the intent of, or the true enjoyment of the performers depicted in the films. The goal of this study was to examine the depictions of a large-scale sample of pornographic videos. The hope is for researchers to take this knowledge and apply it to future scholarship.

As health researchers continue to explore sexual socialization and sexual health education particularly in America, it is important to know what sexual scripts depicted in online pornography may be affecting viewers. This study found depictions of aggression against women are relatively common, although not ubiquitous in online pornography. There may be multiple available scripts available to consumers; including one that contains normative aggression against women, and another that does not. Given the debate over what constitutes consensual aggression in pornography, an important next step in this line of research is to investigate the impact of aggressive scripts in pornography and non-aggressive scripts on sexual consent attitudes and behaviors. Both scholars and health practitioners need a better grasp of sexual consent and the multifaceted way individuals learn sexual consent scripts. The current study paints a picture of pornography that is not as bleak as some previous research, but still suggests there is need for attention and continued research in the effects of aggression in pornography.

Notes

A scene was operationalized as a person or partners undertaking a sexual experience in the same place. Coders were instructed not to count introductions or product advertisements as a separate scene. Complete changes in actors and/or place with new sexual behavior was considered a new scene.

References

Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography. (1986). Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography, Final Report. US Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000824987.

Aubrey, J. S., & Frisby, C. M. (2011). Sexual objectification in music videos: A content analysis comparing gender and genre. Mass Communication and Society, 14(4), 475–501.

Baer, J. L., Kohut, T., & Fisher, W. A. (2015). Is pornography use associated with anti-woman sexual aggression? Re-examining the confluence model with third variable considerations. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 24(2), 160–173.

Ballonoff Suleiman, A., Lin, J. S., & Constantine, N. A. (2016). Readability of educational materials to support parent sexual communication with their children and adolescents. Journal of Health Communication, 21(5), 534–543.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26.

Barron, M., & Kimmel, M. (2000). Sexual violence in three pornographic media: Toward a sociological explanation. Journal of Sex Research, 37(2), 161–168.

Bell, M. E., Turchik, J. A., & Karpenko, J. A. (2014). Impact of gender on reactions to military sexual assault and harassment. Health and Social Work, 39(1), 25–33.

Bridges, A. J., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E., Sun, C., & Liberman, R. (2010). Aggression and sexual behavior in best-selling pornography videos: A content analysis update. Violence Against Women, 16(10), 1065–1085.

Bronstein, C. (2011). Battling pornography: The American feminist anti-pornography movement, 1976–1986. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Check, J. V., & Malamuth, N. M. (1986). Pornography and sexual aggression: A social learning theory analysis. Communication Yearbook, 9, 181–213.

Cogin, J., & Fish, A. (2009). Sexual harassment: A touchy subject for nurses. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 23(4), 442–462.

del Carmen Herrera, M., Herrera, A., & Expósito, F. (2017). To confront versus not to confront: Women’s perception of sexual harassment. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 10(1), 1–7.

Diamond, M., Jozifkova, E., & Weiss, P. (2011). Pornography and sex crimes in the Czech Republic. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(5), 1037–1043.

Dillman Carpentier, F. R., Stevens, E. M., Wu, L., & Seely, N. (2017). Sex, love, and risk-n responsibility: A content analysis of entertainment television. Mass Communication and Society, 20(5), 686–709.

Donnerstein, E. (1984). Pornography: Its effect on violence against women. In N. M. Malamuth & E. Donnerstein (Eds.), Pornography and sexual aggression (pp. 53–81). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Dworkin, A. (1981). Men possessing women. New York, NY: Perigee Books.

Evans, W. D., Davis, K. C., Ashley, O. S., & Khan, M. (2012). Effects of media messages on parent–child sexual communication. Journal of Health Communication, 17(5), 498–514.

Ferguson, C. J., & Hartley, R. D. (2009). The pleasure is momentary…the expense damnable? The influence of pornography on rape and sexual assault. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(5), 323–329.

Fisher, D. A., Hill, D. L., Grube, J. W., Bersamin, M. M., Walker, S., & Gruber, E. L. (2009). Televised sexual content and parental mediation: Influences on adolescent sexuality. Media Psychology, 12(2), 121–147.

Fox, J., & Tang, W. Y. (2017). Women’s experiences with general and sexual harassment in online video games: Rumination, organizational responsiveness, withdrawal, and coping strategies. New Media & Society, 19(8), 1290–1307.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206.

Fritz, N., & Paul, B. (2017). From orgasms to spanking: A content analysis of the agentic and objectifying sexual scripts in feminist, for women, and mainstream pornography. Sex Roles, 77(9–10), 639–652.

Gorman, S., Monk-Turner, E., & Fish, J. N. (2010). Free adult Internet web sites: How prevalent are degrading acts? Gender Issues, 27(3–4), 131–145.

Hald, G. M., Malamuth, N. N., & Lange, T. (2013). Pornography and sexist attitudes among heterosexuals. Journal of Communication, 63(4), 638–660.

Hald, G. M., Malamuth, N. M., & Yuen, C. (2010). Pornography and attitudes supporting violence against women: Revisiting the relationship in nonexperimental studies. Aggressive Behavior, 36(1), 14–20.

Hust, S. J., Brown, J. D., & L’Engle, K. L. (2008). Boys will be boys and girls better be prepared: An analysis of the rare sexual health messages in young adolescents’ media. Mass Communication & Society, 11(1), 3–23.

Hust, S. J., Marett, E. G., Lei, M., Chang, H., Ren, C., McNab, A. L., & Adams, P. M. (2013). Health promotion messages in entertainment media: Crime drama viewership and intentions to intervene in a sexual assault situation. Journal of Health Communication, 18(1), 105–123.

Jones, R. K., & Biddlecom, A. E. (2011). Is the internet filling the sexual health information gap for teens? An exploratory study. Journal of Health Communication, 16(2), 112–123.

Klaassen, M. J., & Peter, J. (2015). Gender (in) equality in Internet pornography: A content analysis of popular pornographic Internet videos. Journal of Sex Research, 52(7), 721–735.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lerner, J. E., & Hawkins, R. L. (2016). Welfare, liberty, and security for all? US sex education policy and the 1996 Title V Section 510 of the Social Security Act. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(5), 1027–1038.

Lindberg, L. D., Maddow-Zimet, I., & Boonstra, H. (2016). Changes in adolescents’ receipt of sex education, 2006–2013. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(6), 621–627.

Linz, D. (1989). Exposure to sexually explicit materials and attitudes toward rape: A comparison of study results. Journal of Sex Research, 26(1), 50–84.

Linz, D., Penrod, S. D., & Donnerstein, E. (1987). The attorney general’s commission on pornography: The gaps between “findings” and facts. Law & Social Inquiry, 12(4), 713–736.

MacKinnon, C. A. (1984). Not a moral issue. Yale Law & Policy Review, 2(2), 321–345.

Malamuth, N. M. (2018). “Adding fuel to the fire”? Does exposure to non-consenting adult or to child pornography increase risk of sexual aggression? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 41, 74–89.

Malik, C., & Wojdynski, B. W. (2014). Boys earn, girls buy: Depictions of materialism on US children’s branded-entertainment websites. Journal of Children and Media, 8(4), 404–422.

McKee, A. (2005). The objectification of women in mainstream pornographic videos in Australia. Journal of Sex Research, 42(4), 277–290.

McKee, A., Byron, P., Litsou, K., & Ingham, R. (2020). An interdisciplinary definition of pornography: Results from a global Delphi panel. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 1085–1091.

Monk-Turner, E., & Purcell, H. C. (1999). Sexual violence in pornography: How prevalent is it? Gender Issues, 17(2), 58–67.

Paasonen, S., Nikunen, K., & Saarenmaa, L. (2007). Pornification: Sex and sexuality in media culture. Oxford, England: Berg Publishers.

Paul, P. (2007). Pornified: How pornography is transforming our lives, our relationships, and our families. New York: Times Books.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2007). Adolescents’ exposure to a sexualized media environment and their notions of women as sex objects. Sex Roles, 56(5–6), 381–395.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2011). The influence of sexually explicit internet material on sexual risk behavior: A comparison of adolescents and adults. Journal of Health Communication, 16(7), 750–765.

Pornhub Insights. (2019). The 2019 year in review. Retrieved from: https://www.pornhub.com/insights/2019-year-in-review.

Potter, W. J., & Levine-Donnerstein, D. (1999). Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 27(3), 258–284.

Rothman, E. F., Kaczmarsky, C., Burke, N., Jansen, E., & Baughman, A. (2015). “Without porn…I wouldn’t know half the things I know now”: A qualitative study of pornography use among a sample of urban, low-income, Black and Hispanic youth. Journal of Sex Research, 52(7), 736–746.

Shor, E., & Golriz, G. (2019). Gender, race, and aggression in mainstream pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(3), 739–751.

Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2015). The role of mass media in adolescents’ sexual behaviors: Exploring the explanatory value of the three-step self-objectification process. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(3), 729–742.

Vandenbosch, L., & van Oosten, J. M. (2017). The relationship between online pornography and the sexual objectification of women: The attenuating role of porn literacy education. Journal of Communication, 67(6), 1015–1036.

Vannier, S. A., Currie, A. B., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2014). Schoolgirls and soccer moms: A content analysis of free “teen” and “MILF” online pornography. Journal of Sex Research, 51(3), 253–264.

Waugh, I. M. (2010). Examining the sexual harassment experiences of Mexican immigrant farmworking women. Violence Against Women, 16(3), 237–261.

Wright, P. J. (2011). 14 Mass media effects on youth sexual behavior assessing the claim for causality. Communication Yearbook, 35, 343–386.

Wright, P. J., Sun, C., Steffen, N. J., & Tokunaga, R. S. (2015). Pornography, alcohol, and male sexual dominance. Communication Monographs, 82(2), 252–270.

Wright, P. J., & Tokunaga, R. S. (2016). Men’s objectifying media consumption, objectification of women, and attitudes supportive of violence against women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(4), 955–964.

Wright, P. J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Kraus, A. (2016). A meta-analysis of pornography consumption and actual acts of sexual aggression in general population studies. Journal of Communication, 66(1), 183–205.

Zhou, Y., & Paul, B. (2016). Lotus blossom or dragon lady: A content analysis of “Asian women” online pornography. Sexuality and Culture, 20(4), 1083–1100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B. et al. A Descriptive Analysis of the Types, Targets, and Relative Frequency of Aggression in Mainstream Pornography. Arch Sex Behav 49, 3041–3053 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01773-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01773-0