Abstract

Cheating—a general term for extradyadic romantic or sexual behavior that violates expectations in a committed romantic relationship—is common and leads to a number of poor outcomes. Religion has historically influenced conceptions of romantic relationships, but societal attitudes about religion are in flux as many seek to retain spirituality even as affiliations with formal religion decrease. The present study evaluated a potential predictor of cheating that is more spiritual than formally religious, the “psychospiritual” concept of relationship sanctification (i.e., the idea that one’s relationship itself is sacred). In a sample of college students in committed relationships (N = 716), we found that higher levels of self-reported relationship sanctification were associated with a lower likelihood of both physical and emotional cheating even when accounting for plausible alternate explanations (general religiosity, problematic alcohol use, and trait self-control). This association was mediated via permissive sexual attitudes; specifically, higher levels of sanctification were associated with less permissive sexual attitudes which, in turn, predicted a lower likelihood of emotional and physical cheating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cheating—a general term for extradyadic romantic or sexual behavior that violates the expectations in a committed romantic relationship—is common in romantic relationships. Approximately 20–40% of men and 20–25% of women will cheat on their spouse in their lifetime; in any 1 year, 2.3% of people will cheat on their spouse (Greeley, 1994; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994 as cited in Whisman, Gordon, & Chatav, 2007; Whisman & Snyder, 2007). As more people choose to marry at later ages or to forgo marriage altogether in favor of cohabitation (Geiger & Livingston, 2018), understanding cheating in all types of romantic relationships (not just marriage) is important. Religion has historically influenced people’s conceptions of romantic relationships, but societal attitudes about religion are in flux as people wish to retain elements of spirituality even as they trend away from formal religion (Pew Research Center, 2014). The present study evaluates a potential predictor of cheating that is more spiritual than formally religious, the concept of relationship sanctification.

Cheating Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Consequences

Defining what constitutes cheating is difficult since definitions may vary between couples and individuals. Although nearly everyone agrees that clandestine sexual intercourse with someone other than the committed partner would constitute cheating, many other behaviors are seen as cheating by those in committed relationships (McAnulty & Brineman, 2007). A broad definition, advanced by Blow and Hartnett (2005), suggests that the essence of cheating is a sexual or emotional act that occurs outside of the committed relationship in a way that violates expectations of sexual and emotional exclusivity.

Cheating is more common in unmarried couples than in married couples. Between 30 and 70% of individuals in dating relationships report a lifetime incidence of cheating (Hansen, 1987; Wiederman & Hurd, 1999), and 10–15% of cohabitating partners have report cheating in their current unions (Frisco, Wenger, & Kreager, 2017; Treas & Giesen, 2000). In college student samples, between 50 and 57% of students report cheating in their current romantic relationship (Braithwaite, Lambert, Fincham, & Pasley, 2010; Feldman & Cauffman, 1999).

Cheating is a robust predictor of relationship dissolution. For example, one study found that approximately 31% of divorces were preceded by cheating (South & Lloyd, 1995). Another study showed that 31% of separated men and 45% of separated women cited cheating as a reason for separation (Atwood & Seifer, 1997). Cheating is the most commonly cited reason for divorce (Amato & Previti, 2003) and doubles the likelihood of divorce when controlling for key distal and proximal variables (Amato & Rogers, 1997).

Among those in dating relationships, cheating is associated with poorer mental and physical health for both the partner who cheated, and the aggrieved partner; those who cheat report psychological distress and victims of cheating report feelings of guilt, depression, and grief over the loss of the relationship (Hall & Fincham, 2009). Approximately 33% of young adults report inconsistent or no condom use (Gerrard, Gibbons, & Bushman, 1996; Weaver, MacKeigan, & MacDonald, 2011) and individuals who cheat often keep their cheating secret. Vail-Smith, Whetstone, and Knox (2010) found that 33.2% of participants who had cheated sexually often lied about their previous sexual partners. This secrecy can put partners of cheaters unknowingly at risk of sexually transmitted infections.

Risk factors for marital cheating include marriage before age 20, previous divorce (Atkins, Baucom, & Jacobson, 2001), and low sexual or emotional satisfaction (Wiggins & Lederer, 1984). For couples who are not married, risk factors include poor relationship quality (Barta & Kiene, 2005; Wilkins & Dalessandro, 2013), having cheated previously (Wiederman & Hurd, 1999), and permissive sexual attitudes (McAnulty & Brineman, 2007). In both married and unmarried couples, cheating may occur when the cheater feels the relationship is ending (Brand, Markey, Mills, & Hodges, 2007).

Barta and Kiene (2005) examined emotional and sexual motivations for cheating and found that sexual motivations were predicted by male gender, lower age, and more permissive sexual attitudes, whereas emotional motivations (e.g., dissatisfaction, neglect, anger) were predicted by female gender and the personality traits of extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness (Barta & Kiene, 2005). Recently, researchers have included an emotional relationship with someone other than one’s partner in definitions of cheating because individuals involved in extradyadic emotional relationships are at an elevated risk of relationship dissolution (Negash, Cui, Fincham, & Pasley, 2014). Thus, our review of the literature suggests that cheating may have a physical, sexual, or emotional form and that each appears to be associated with harm to the relationship (Fincham & May, 2017).

Cheating and Religiosity in Romantic Relationships

Societal trends in marriage make understanding unmarried romantic relationships an even more relevant task. Among people ages 18–32, the marriage rate decreased from 48% in 1980 to 26% in 2013 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Thus, more people are spending more time in romantic relationships other than marriage and, as we reviewed above, those in these relationships are more likely to experience cheating. Several studies have found that low religiosity is a predictor of cheating in married samples (Atkins et al., 2001; Atkins & Kessel, 2008; Burdette, Ellison, Sherkat, & Gore, 2007). Other studies have found that religiosity and religious affiliation are not significant predictors of cheating behaviors (Edwards & Booth, 1976). When specific components of religiosity are examined, some are associated with infidelity, but others are not (Esselmont & Bierman, 2014). These inconsistent findings highlight the need to better understand potential moderators of the relationship between religiosity and cheating behavior.

Religiosity is typically defined as an orientation toward and involvement within a religious community and its practices. For most religions, people who identify as “strong” members of their religion report significantly lower rates of cheating than those who identify as “weak” members of their religion (Burdette et al., 2007). There are also data to suggest that those who are religious are less likely to cheat on their spouses than nonreligious individuals (Atkins & Kessel, 2008; Dollahite & Lambert, 2007), and religious behaviors like prayer are associated with less cheating (Fincham, Lambert, & Beach 2010; Pereira, Taysi, Orcan, & Fincham, 2014).

Atkins et al. (2001) found an interaction between religiosity and marital satisfaction regarding cheating; people who reported that their relationships were “pretty happy” or “not too happy” demonstrated little to no effect of religiosity on fidelity, while individuals who reported that their marriages were “very happy” demonstrated a strong effect of religiosity on fidelity. Individuals who never attended religious services were 2.5 times more likely to engage in extramarital sex compared with those who attended religious services more than once a week.

Religiosity has also been found to have an indirect effect on marital cheating. In a longitudinal study investigating couples who had been married for more than 12 years, religiosity was found to increase marital happiness, which is associated with lower rates of cheating (Tuttle & Davis, 2015). However, religiosity as a global construct describes only behaviors, orientation, and involvement within a religious community. Sanctification is a related construct that describes how the experience of the sacred changes human behavior and emotions (Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). Sanctification has been shown to have an incremental impact on predicting relationships outcomes compared to religiosity, but no research has yet examined whether sanctification predicts cheating behavior even when accounting for general religiosity.

Because the rising generation is trending away from formal religion with some retaining elements of spirituality, examining questions about religion and spirituality in a way that acknowledges current trends is important. Formal religiosity, as we have just reviewed, is a robust predictor of infidelity, even if there is some nuance to that relationship (Esselmont & Bierman, 2014), but formal religion is becoming less of a feature among those entering adulthood. In a recent survey, only 51% of Americans identified as religious. A slim minority (49%) defined themselves as not traditionally religious with 33% saying they were neither spiritual nor religious and 18% identifying as spiritual but not religious (Public Religion Research Institute, 2017). As society evolves, our understanding of religious constructs needs to keep pace so we can understand the experiences of those who maintain elements of spirituality outside of formal religion. We seek to extend the current literature by examining whether sanctification predicts cheating among those in dating relationships while accounting for the established effect of religiosity.

Sanctification of Relationships

Religiosity describes elements of religious observance and belief such as church attendance, orthodoxy of beliefs, and certitude in particular doctrines, but sanctification describes internal processes “through which aspects of life are perceived as having divine character and significance” (Pargament & Mahoney, 2005, p. 183). As such, sanctification does not require adherence to or belief in a particular religion or worldview, only that one sees certain things, such as a relationship, as sacred. For that reason, sanctification has been termed a psychospiritual construct (Mahoney, Pargament, & Murray-Swank, 2001), rather than a formally religious construct. Researchers and lay people likely have different ideas about what differentiates religion and spirituality, but in the literature religion tends to be thought of more in terms of institutional membership and shared beliefs, whereas spirituality tends to include a more personal sense of the sacred in the context of everyday life (Zinnbauer, Pargament, & Scott, 1999). Sanctification is a spiritual concept because it imbues sacredness or meaning to something without any need for connection to an institution, canon of scripture, or established dogma. People report sanctification of parent–child relationships, pregnancy, sexuality, strivings, the body, work, and the environment (Pomerleau, Wong, & Mahoney, 2015), but the majority of research on sanctification has focused on relationships, since many individuals seem to see this aspect of life as sacred and holy, whether they are formally religious or not.

Sanctification of marriage occurs in couples of various religious and spiritual backgrounds (Butler & Harper; 1994; Lauer, 1985; Stanley, Trathen, McCain, & Bryan, 1998; Tarakeshwar, Pargament, & Mahoney, 2003) and is thus relevant to people from many religious faiths and those who do not affiliate with a particular denomination or who do not describe themselves as religious (Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). Although studies do not report the prevalence of sanctification, per se (since it is conceptualized as a continuous, not a categorical construct), studies that examine sanctification tend to show that this variable is fairly normally distributed in most samples with sample means that suggest moderately high levels of sanctification.Footnote 1 Sanctification predicts marital satisfaction and well-being at the dyadic level (Rusu et al., 2015; Stafford, 2016). Couples who sanctify their relationship experience less marital conflict, including verbal aggression, and experience more verbal collaboration (Mahoney et al., 1999). Stafford, David, and McPherson (2014) found a relationship between sanctification and positive marital quality, even when controlling for forgiveness and sacrifice. Moreover, the partners of those who sanctify their relationship are more relationally satisfied (a partner effect) because they invest more time and energy into improving the quality of their relationship (Stafford, 2016).

Permissive Sexual Attitudes and Sanctification

Because sanctification elevates relationships to the realm of the sacred, we hypothesized that sanctification would predict less cheating over time via a reduction in permissive attitudes toward sex. Often measured using the term sociosexual orientation, more permissive sexual attitudes are generally operationalized by assessing whether the respondent uncouples love or commitment from sexual activity (e.g., “Sex without love is okay”; Penke & Asendorpf, 2008). Permissive sexual attitudes are associated with less commitment, more permissive perceptions of cheating, and sexual cheating behavior (Rodrigues, Lopes, & Pereira, 2017) and a lower likelihood of admitting to cheating when it has occurred (Seedall, Houghtaling, & Wilkins, 2013). If one elevates a relationship to a spiritual status, intimate behaviors would likely be seen as inappropriate outside of the committed partnership, but existing research has yet to examine sanctification, permissive sexual attitudes, and cheating behaviors to illuminate the potential associations among these constructs.

Spirituality is negatively correlated with sexual permissiveness in college students (r = − .43; Murray, Ciarrocchi, & Murray-Swank, 2007), though these effects may be more robust for men than for women (Brelsford, Luquis, & Murray-Swank, 2011). Because permissive sexual attitudes are associated with higher rates of cheating (McAnulty & Brineman, 2007), sexual permissiveness is a likely mechanism linking relationship sanctification and cheating. In the present study, we hypothesized that sexually permissive attitudes would mediate the association between relationship sanctification and cheating. To provide a more rigorous test of our hypothesis, we controlled for the potentially confounding influence of trait self-control (McAlister, Pachana, & Jackson, 2005) and problematic alcohol use (Fincham & May, 2017) as these constructs have been associated with cheating among emerging adults. We also controlled for general religiosity in order to test the unique effect of sanctification on cheating.

Method

Participants

These data were drawn from a larger data collection effort that explored the course of emerging adulthood in college (Project Relate; Braithwaite et al., 2010). Participants were recruited from a public university in the Southeastern U.S. Students in an introductory family science course were invited to participate in order to earn course credit. Prior to collecting data, institutional review board approval was obtained for all procedures. Participants completed an online survey at the beginning, mid-term, and end of the semester.

To increase statistical power, we combined the data from the two separate semesters (participants were independent between semesters) that both had variables relevant to our research questions (N = 1959). Our “stopping rule” was to include all archival data from semesters that had the variables we hoped to examine. Given our interest in cheating among those in committed, non-marital relationships, only those who were in a committed dating relationship were included (whether they were same-sex or opposite-sex relationships since we had no a priori reason to suggest sexual orientation would moderate these associations). Thus, we excluded those who were single (n = 1101), non-exclusively dating (n = 103), engaged (n = 21), or married (n = 4). Participants were excluded if they did not fall in the age range associated with emerging adulthood, 18–25 (n = 61; Arnett, 2000). This resulted in a sample of N = 716. No other exclusions were made. The demographic composition of our sample is given in Table 1. To increase our transparency and to foster open science, we have included our data and code on the OSF Web site (https://osf.io/8dcfm/?view_only=24e36316c977408fad552fb07b8040f4).

Measures

Assessment of Sanctification Sanctification is often assessed through the Manifestation of God scale (Murray-Swank, Pargament, & Mahoney, 2005; Swank, Mahoney, & Pargament, 2000) and the Sacred Qualities scale (Mahoney et al., 1999; Swank et al., 2000). The Manifestation of God scale asks participants whether they sense God’s presence in their relationship without specifying a particular god. The Sacred Qualities scale asks whether participants see their relationship as sacred. Both scales have been correlated with global measures of religiosity. The Manifestation of God items are strongly correlated with religiosity (r = .71). Sacred Qualities items are moderately correlated with religiosity (r = .43 for wives and r = .39 for husbands; Mahoney et al., 1999), suggesting it may cover a broader spiritual domain than religiosity.

Because our data were archival and included only one item from the Manifestation of God scale and one item from the Sacred Qualities scale, we assessed relationship sanctification using these two available items. From the Manifestation of God scale, we used the item “I sense God’s presence in my relationship with my partner.” From the Sacred Qualities scale, we used the item, “My relationship with my partner is holy and sacred.” These two items were recommended by A. Mahoney (personal communication, October 21, 2005) when the original study was being designed. Participants rated their agreement with each item on a five-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more sanctification. The distribution of responses to these items is shown in Fig. 1. The mean response to these two items was used to generate the total scale score. Descriptive statistics for this and all other measures are shown in Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha for this two-item scale was .85. Our item from the Manifestation of God scale correlated with our general religiosity scale (r = .57) and our item from the Sacred Quality scale correlated with our general religiosity scale (r = .44). This pattern of correlations is consistent with the pattern observed in the measurement paper for the full scale described above (Mahoney et al., 1999), suggesting good psychometrics, especially for a two-item measure.

Cheating over the Course of an Academic Semester To measure cheating, we used a scale designed for young adult dating relationships that measures both emotional and physical cheating (Drigotas, Safstrom, & Gentilia, 1999). This scale was chosen because of its sensitivity to the issue of social desirability. Specifically, the scale was developed to provide “a scale that could capture this behavior in such a manner that participants would be likely both to divulge information and to do so honestly” (Drigotas et al., 1999, p. 512). Participants were instructed to think of a person to whom they were most attracted that was not their current relationship partner. Next, to help participants feel more comfortable divulging potential cheating behavior, participants are asked a series of questions that culminate in two questions that ask about the specific occurrence of cheating behavior: “Have you done anything that you consider to be physically unfaithful?” and “Have you done anything that you consider to be emotionally unfaithful?” Responses were coded 0 = no and 1 = yes. Participants were coded as having physically cheated if they responded “yes” at either mid-semester or the end of the semester. The same coding approach was used for emotional cheating.

Sexual Attitudes To measure sexual attitudes, we used two items from the sexual attitudes subscale from The Revised Sociosexual Orientation Inventory (SOI-R; Penke & Asendorpf, 2008): “Sex without love is OK,” and “I can imagine myself being comfortable and enjoying ‘casual’ sex with different partners.”Footnote 2 Responses were scored on a nine-point Likert scale. The mean response to these two items was used to generate the total scale score. Items were scored so higher scores indicated more permissive sexual attitudes. In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha for this two-item scale was .85 (.87 for males, .84 for females).

Control Variables We tested whether our specified relationships hold when accounting for plausible alternative explanations for cheating. Specifically, we controlled for trait self-control, problematic alcohol use, and general religiosity.

Trait self-control was assessed using the Brief Self-Control Scale (α for the current study = .84; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). The Brief Self-Control Scale includes items such as “I am good at resisting temptation” and “I refuse things that are bad for me” measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very much). Researchers found good internal consistency (α = .83 for Brief Self-Control Scale) and test-retest reliability (.87). Additionally, high scores on the Brief Self-Control Scale predicted higher grades, fewer impulse control problems, better psychological adjustment, better interpersonal relationships, more guilt, and less shame in their college validation sample.

Problematic alcohol use was measured using the College Alcohol Problems Scale (CAPS; Maddock, Laforge, Rossi, & O’Hare, 2001). CAPS is a two-factor scale measuring the social and personal problems associated with alcohol use measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = never/almost never to 5 = very often). All items have the stem “As a result of drinking alcoholic beverages I…” with items including “engaged in unplanned sexual activity” and “felt sad, blue, or depressed.” The scale was original subjected to EFA, which suggested the two-factor model. A CFA showed the model fits well (NFI .95, CFI .96). Additionally, CAPS was significantly correlated with drinking-related variables such as number of days with drinking and number of drinks per occasion.

General religiosity was assessed using two items on a four-point Likert scale: “How often do you attend religious services?” (ranging from Never, or almost never to One or more times per week) and “How important is religion in your life?” (ranging from Not Important to Very Important). The mean response to these two items was used to generate the total scale score where higher scores indicate more religiosity. Cronbach’s alpha for this two-item scale was .83 (.83 for males, .82 for females). Collinearity diagnostic tests were below the commonly used conservative cutoff of VIF > 5.0 for all variables (mean VIF = 1.35, ranging from 1.24 for self-control to 1.49 for religiosity).

Results

Analytic Approach

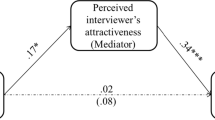

We used generalized structural equation models (GSEMs) in Stata to examine whether sanctification was associated with physical cheating (cheated = 1, did not = 0) over the course of an academic semester (approximately 4 months). The same model was used to examine whether sanctification was associated with emotional cheating (cheated = 1, did not = 0). We ran separate models for physical and emotional cheating outcomes (Figs. 2 and 3). Because these outcomes are binary, we estimated them using a logistic model. Using an SEM approach to tests of mediation is useful because it allows for a full test of mediation in a single model rather than a series of separate regressions (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

To ensure that within-semester correlations were not driving observed associations (since we aggregated across two semesters), we conducted a preliminary test of moderation by semester for both outcome variables. These showed that the semester of data collection did not have a direct (B = − 1.17, z = − 1.85, p > .05 for physical infidelity and B = − .72, z = − 1.33, p > .05 for emotional infidelity) or interactive (B = .33, z = 1.56, p > .05 for physical infidelity and B = 0.14, z = 0.85, p > .05 for emotional infidelity) effect on outcomes. Given the imbalance of men and women in our sample, we also conducted preliminary tests for potential moderation by sex. These showed that biological sex did not have a direct (B = − .00, z = − 0.01, p > .05 for physical infidelity and B = − .10, z = − 0.15, p > .05 for emotional infidelity) or interactive (B = .06, z = 0.24, p > .05 for physical and B = .12, z = 0.58, p > .05 for emotional) effect with our predictor, as well as our mediator (direct effects B = − .31, z = − 0.55, p > .05 for physical and B = .18, z = 0.37, p > .05 for emotional; interactive effects B = 0.90, z = 0.94, p > .05 for physical infidelity and B = .02, z = 0.24, p > .05 for emotional infidelity) on either outcome.

Descriptive Statistics

Twenty-one percent of men and 16% of women reported cheating physically over the course of an academic semester. Emotional cheating was somewhat more common; 30% of men and 28% of women reported cheating emotionally in the same time period. For men, the correlation between physical cheating and emotional cheating was r = .51. For women, the same correlation was r = .40, providing evidence that these two phenomena are moderately related, but also clearly distinct (sharing between 16 and 26% of variance). As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, all of our covariates were significant predictors of physical (self-control z = − 2.01, p < .05; religiosity z = 2.63, p < .01; alcohol use z = 2.17, p < .05; sociosexual attitudes z = 3.81, p < .01) and emotional cheating (self-control z = − 2.74, p < .01, religiosity; z = 3.79, p < .01; alcohol use z = 2.89, p < .01; sociosexual attitudes z = 2.51, p < .01) providing a particularly rigorous test of the incremental utility of sanctification as a potential predictor of cheating. Of note, in both models, religiosity has a positive relationship to cheating. These observations are likely amplified by suppression effects as the zero-order correlations between religiosity and cheating (Table 3) are not significant for men (r = .09 for physical cheating, r = .12 for emotional cheating) or women (r = − .06 for physical cheating, r = .01 for emotional cheating).

Does Sanctification Predict Cheating?

When accounting for the statistically significant impact of all covariates in the model (Fig. 2), sanctification was associated with less emotional cheating (OR .78, 95% CI [.64, .95]). A one-point increase on the sanctification scale was associated with a 22% reduction in the likelihood of emotional cheating. To illustrate the practical significance of these findings, we estimated predicted values with the margins post-estimation command in Stata. Holding the effect of all covariates at their means—including our hypothesized mediator, permissive sexual attitudes—those with the lowest possible sanctification score had a 38.1% probability of emotionally cheating over the course of an academic semester compared to a 19.8% probability of cheating for those with the highest possible sanctification score.

Sanctification was also found to be associated with less physical cheating (OR .74, 95% CI [.58, .94]) when controlling for the statistically significant impact of all other variables in the model (Fig. 2). A one-point increase on the sanctification scale was associated with a 26% reduction in the likelihood of physical cheating. Predicting out of our model, those with the lowest possible sanctification score had a 25.4% probability of physically cheating over the course of an academic semester compared to a 9.9% probability of cheating for those with the highest possible sanctification score.

Do Permissive Sexual Attitudes Mediate This Association? We tested whether permissive sexual attitudes mediated the impact of sanctification on cheating. Stata’s command for testing indirect effects (teffects) is not available in generalized structural equation model (GSEM), but estimates of the indirect effect (a × b) can be derived using the nonlinear combinations of estimators command (nlcom).

Following procedures for assessing mediation outlined by Shrout and Bolger (2002), we observed a significant indirect effect for emotional cheating (a × b OR .94, 95% CI [.89, .99]), indicating that sanctification reduced emotional cheating via the mediator of less permissive sexual attitudes. We derived an estimate of c that omitted the impact of the mediator but included the impact of all the covariates (c path OR 0.51) in order to derive an effect ratio (a × b/c). Including the covariates in the model provides a more conservative test of our indirect effect than if we were to omit them, but we reasoned that specifying the model this way reflects the “real world” more accurately. Our effect ratio indicated that 12% of the impact of sanctification on emotional cheating operates via less permissive sexual attitudes when accounting for our covariates.

We also observed a significant indirect effect for physical cheating (a × b OR .89, 95% CI [.84, .95]), indicating that sanctification reduces physical cheating via the mediator of less permissive sexual attitudes. Our effect ratio for physical cheating (obtained using the same procedure as for emotional cheating) indicated that 38% of the impact of sanctification on physical cheating operates via less permissive sexual attitudes.

These data provide evidence that higher levels of sanctification were associated with less permissive sexual attitudes and, in turn, less likelihood of cheating. Although permissive sexual attitudes mediated the impact of sanctification for both physical and emotional cheating, the proportion of the effect mediated through permissive sexual attitudes was more than double for physical cheating (effect ratio = 38%) compared to emotional cheating (effect ratio = 12%). Finally, even when accounting for the indirect effect, a direct effect for sanctification on both outcomes remained, suggesting partial mediation.

Discussion

The present study evaluated cheating in unmarried, committed relationships in emerging adulthood (ages 18–25), a group with high rates of cheating. In line with our original hypothesis, we found that higher levels of self-reported sanctification were associated with a lower likelihood of cheating on one’s partner. This effect held for both emotional and physical cheating. The association was mediated via permissive sexual attitudes; specifically, higher levels of sanctification were associated with less permissive sexual attitudes which, in turn, predicted a lower likelihood of emotional and physical cheating.

These findings were consistent with previous research about permissive sexual attitudes and cheating (Brelsford et al., 2011; Murray et al., 2007), but extend these findings to show that sanctification incrementally improves our prediction of cheating among emerging adults. It is interesting to note that permissive sexual attitudes were a stronger mediator for the relationship between sanctification and physical cheating than sanctification and emotional cheating, explaining approximately twice as much variance. This could be due to our measurement of permissive sexual attitudes using the SOI-R, which focuses more on sexual behavior rather than on behavior associated with emotional cheating. Another possibility is that sanctification actually has a stronger protective effect for concrete sexual behavior than the more nebulous behaviors associated with emotional cheating. Future research with richer measurement of cheating could clarify this issue (see Thompson & O’Sullivan, 2016). For example, given that participants were asked to judge whether they had done something that was physically or emotionally unfaithful, it is possible that some variance in these outcomes is explained by more conservative personal definitions of infidelity held by those who are higher in sanctification. This is likely, given the finding that those who sanctify relationships are more likely to see ambiguous behaviors with people outside of the relationship as “wrong” (Selterman & Koleva, 2015).

Concerning permissive sexual attitudes and the distinction between emotional and physical cheating, Treger and Sprecher (2011) found that unrestricted sociosexual orientation was associated with greater distress in response to sexual cheating than to emotional cheating, whereas restricted sociosexual orientation was associated with greater distress in response to emotional cheating. More research is needed to replicate and clarify this finding and to better understand the connections between permissive sexual attitudes and emotional versus physical cheating.

Our research also extends our understanding of sanctification. Theorizing about sanctification indicates that it operates via several pathways; namely, people invest more time and care in sanctified areas, people receive social support from sanctified areas, people are protective of sanctified areas, and adverse consequences follow when a sanctified area is compromised or lost (Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). Our finding that sanctification was associated with less permissive sexual attitudes fits with the protection pathway; specifically, sanctification may promote a form of cognitive protection whereby people resist attitudes that facilitate cheating. However, the cross-sectional nature of our data does not allow us to rule out the possibility that another variable not specified in our model predicts both sanctification and less permissive sexual attitudes. Interdependence models suggest that more commitment to one’s partner leads individuals to derogate attractive alternatives to their partner (Rusbult & Buunk, 1993). Our research hints at a similar process for sanctification, but more research is needed to establish this possibility.

Our study extends research on sanctification by providing evidence that it can operate in relationships other than marriage. Relationships with higher levels of commitment are generally associated with greater well-being (Braithwaite & Holt-Lunstad, 2017; Dush & Amato, 2005); thus, it is not a given that sanctification would operate similarly, or at all, outside of marriage. However, the impact of sanctification appears to differ based on what is being sanctified. For example, the sanctification of sexual intercourse itself, and not a specific relationship, is associated with more frequent sex with more unique partners (Murray-Swank et al., 2005). Thus, more research is needed to understand the conditions under which sanctification is associated with healthy versus risky behaviors.

An interesting and unexpected finding was that our religiosity control variable was significantly associated with more physical and emotional cheating. Although some research has shown that religiosity correlates with more cheating behavior (e.g., Treas and Giesen, 2000), the preponderance of evidence suggests a negative correlation between these two constructs (e.g., Atkins et al., 2001; Atkins & Kessel, 2008; Burdette et al., 2007). In our model, the most likely explanation, given the nonsignificant zero-order correlations between religiosity and cheating, is that when one accounts for sanctification, the residual variance explained by religiosity (i.e., outward religious behavior such as church attendance) actually does correlate with more cheating behavior. This may be especially true in a college student population. More research is needed to determine whether this pattern of findings replicates.

Limitations

Our study required the adaptation of questionnaires typically utilized in marital relationships for an unmarried, college-aged sample; thus, many of our scales were not previously validated. The structure of our questions included the critical elements of the Sacred Qualities scale (Mahoney et al., 1999; Swank et al., 2000) and the Manifestation of God scale (Murray-Swank et al., 2005; Swank et al., 2000), but our questions did not provide as much coverage of the conceptual domains of these constructs as the full scales. Although we provided evidence within our sample for the psychometric properties of our scale, future research would do well to develop measures of sanctification designed specifically for relationships other than marriage. Similarly, our assessment of cheating comprised single items that asked the respondent to indicate whether they felt they had done something physically or emotionally unfaithful. Ceding so much of the construct to the respondent’s judgment likely makes for noisy measurement of the construct. In addition to a better measure of cheating, research is needed to develop a theory of what constitutes cheating in non-marital, romantic relationships. Finally, although we did not observe a different pattern of associations between men and women when we tested for moderation by biological sex, our sample overrepresented women which affects the generalizability of these results. Further, all our participants were college educated which calls into question the generalizability of our findings to all emerging adults.

Conclusion

As marriage rates continue to decrease among emerging adults (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014), there is a need to explore relationship functioning in couples that do not marry. Fifty to fifty-seven percent of college students have reported being in a relationship in which one partner had cheated (Braithwaite et al., 2010; Feldman & Cauffman, 1999). Understanding potentially protective variables like sanctification—a construct relevant to a demographic that is less religious but more spiritual than previous generations—may help us better understand how to promote safe, healthy unions in the years ahead.

Notes

For example, in one of the foundational papers on this topic, a scale that asked whether participants saw God manifest in their marriage had a mean of 67 for men and 72 for women on a scale that ranged from 14 to 98. Similarly, on a scale that assessed whether participants perceived marriage as sacred the mean was 44 for women and 46 for men on a scale that ranged from 9 to 63 (Mahoney et al., 1999).

We initially intended to use all three items from the SOI-R attitudes scale, but in our first wave of data collection Item 3 from the SOI was used and in the second wave of data collection Item 3 from the SOI-R (a different item) was used. Thus, we elected to use only two items.

References

Amato, P. R., & Previti, D. (2003). People’s reasons for divorcing: Gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. Journal of Family Issues,24, 602–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X03254507.

Amato, P. R., & Rogers, S. J. (1997). A longitudinal study of marital problems and subsequent divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family,59, 612–624. https://doi.org/10.2307/353949.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist,55, 469–480. https://doi.org/10.2307/41613313?ref=no-x-route:8aa47aeae636a935d88525be3ad36514.

Atkins, D. C., Baucom, D. H., & Jacobson, N. S. (2001). Understanding infidelity: Correlates in a national random sample. Journal of Family Psychology,15, 735–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.4.735.

Atkins, D. C., & Kessel, D. E. (2008). Religiousness and infidelity: Attendance, but not faith and prayer, predict marital fidelity. Journal of Marriage and Family,70, 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00490.x.

Atwood, J. D., & Seifer, M. (1997). Extramarital affairs and constructed meanings: A social constructionist therapeutic approach. American Journal of Family Therapy,25, 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926189708251055.

Barta, W. D., & Kiene, S. M. (2005). Motivations for infidelity in heterosexual dating couples: The roles of gender, personality differences, and sociosexual orientation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,22, 339–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505052440.

Blow, A. J., & Hartnett, K. (2005). Infidelity in committed relationships II: A substantive review. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31, 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01556.x.

Braithwaite, S., & Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). Romantic relationships and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology,13, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.001.

Braithwaite, S. R., Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., & Pasley, K. (2010). Does college-based relationship education decrease extradyadic involvement in relationships? Journal of Family Psychology,24, 740–745. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021759.

Brand, R. J., Markey, C. M., Mills, A., & Hodges, S. D. (2007). Sex differences in self-reported infidelity and its correlates. Sex Roles,57, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9221-5.

Brelsford, G. M., Luquis, R., & Murray-Swank, N. A. (2011). College students’ permissive sexual attitudes: Links to religiousness and spirituality. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion,21, 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2011.557005.

Burdette, A. M., Ellison, C. G., Sherkat, D. E., & Gore, K. A. (2007). Are there religious variations in marital infidelity? Journal of Family Issues,28, 1553–1581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07304269.

Butler, M. H., & Harper, J. M. (1994). The divine triangle: God in the marital system of religious couples. Family Process,33, 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1994.00277.x.

Dollahite, D. C., & Lambert, N. M. (2007). Forsaking all others: How religious involvement promotes marital fidelity in Christian, Jewish, and Muslim couples. Review of Religious Research,48, 290–307.

Drigotas, S. M., Safstrom, C. A., & Gentilia, T. (1999). An investment model prediction of dating infidelity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 509–524.

Dush, C. M. K., & Amato, P. R. (2005). Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,22, 607–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505056438.

Edwards, J. N., & Booth, A. (1976). Sexual behavior in and out of marriage: An assessment of correlates. Journal of Marriage and the Family,38, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/350551.

Esselmont, C., & Bierman, A. (2014). Marital formation and infidelity: An examination of the multiple roles of religious factors. Sociology of Religion,75, 463–487. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sru036.

Feldman, S. S., & Cauffman, E. (1999). Your cheatin’ heart: Attitudes, behaviors, and correlates of sexual betrayal in late adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence,9, 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327795jra0903_1.

Fincham, F. D., Lambert, N. M., & Beach, S. R. H. (2010). Faith and unfaithfulness: Can praying for your partner reduce infidelity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,99, 649–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019628.

Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W. (2017). Infidelity in romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology,13, 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.008.

Frisco, M. L., Wenger, M. R., & Kreager, D. A. (2017). Extradyadic sex and union dissolution among young adults in opposite-sex married and cohabiting unions. Social Science Research,62, 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.08.013.

Geiger, A., & Livingston, G. (2018) 8 facts about love and marriage in America. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/02/13/8-facts-about-love-and-marriage/.

Gerrard, M., Gibbons, F. X., & Bushman, B. J. (1996). Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychological Bulletin,119, 390–409. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390.

Greeley, A. (1994). Marital infidelity. Society,31(4), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02693241.

Hall, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Psychological distress: Precursor or consequence of dating infidelity? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,35, 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208327189.

Hansen, G. L. (1987). Extradyadic relations during courtship. Journal of Sex Research,23, 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498709551376.

Lauer, E. F. (1985). The holiness of marriage: Some new perspectives from recent sacramental theology. Studies in Formative Spirituality,6, 215–226.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Maddock, J. E., Laforge, R. G., Rossi, J. S., & O’Hare, T. (2001). The College Alcohol Problems Scale. Addictive Behaviors,26, 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00116-7.

Mahoney, A., Pargament, K. I., Jewell, T., Swank, A. B., Scott, E., Emery, E., & Rye, M. (1999). Marriage and the spiritual realm: The role of proximal and distal religious constructs in marriage functioning. Journal of Family Psychology,13, 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.13.3.321.

Mahoney, A., Pargament, K. I., Murray-Swank, A., & Murray-Swank, N. (2001). Religion and the sanctification of family relationships. Review of Religious Research,40, 220–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/3512384.

McAlister, A., Pachana, N., & Jackson, C. (2005). Predictors of young dating adults’ inclination to engage in extradyadic sexual activities: A multi-perspective study. British Journal of Psychology,96, 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712605X47936.

McAnulty, R. D., & Brineman, J. M. (2007). Infidelity in dating relationships. Annual Review of Sex Research,18, 94–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10532528.2007.10559848.

Murray, K. M., Ciarrocchi, J. W., & Murray-Swank, N. A. (2007). Spirituality, religiosity, shame and guilt as predictors of sexual attitudes and experiences. Journal of Psychology & Theology,35, 222–234.

Murray-Swank, N. A., Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. (2005). At the crossroads of sexuality and spirituality: The sanctification of sex by college students. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion,15, 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr1503_2.

Negash, S., Cui, M., Fincham, F., & Pasley, K. (2014). Extradyadic involvement and relationship dissolution in heterosexual women university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior,43, 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0213-y.

Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. (2005). Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion,15, 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr1503_1.

Penke, L., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2008). Beyond global sociosexual orientations: A more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,95, 1113–1135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1113.

Pereira, M. G., Taysi, E., Orcan, F., & Fincham, F. (2014). Attachment, infidelity, and loneliness in college students involved in a romantic relationship: The role of relationship satisfaction, morbidity, and prayer for partner. Contemporary Family Therapy,36, 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-013-9289-8.

Pew Research Center. (2014). Religious landscape study. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from http://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/.

Pomerleau, J., Wong, S., & Mahoney, A. (2015, April). Sanctification: A meta-analytic review. Society for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality Newsletter (pp. 1–4). https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/psychology/psy-spirit-fam-mahoney/Sanctification%20Poster%20Handout%204-15.pdf.

Public Religion Research Institute. (2017). New survey: One in five Americans are spiritual but not religious. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.prri.org/press-release/new-survey-one-five-americans-spiritual-not-religious/.

Rodrigues, D., Lopes, D., & Pereira, M. (2017). Sociosexuality, commitment, sexual infidelity, and perceptions of infidelity: Data from the second love web site. Journal of Sex Research,54, 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1145182.

Rusbult, C. E., & Buunk, B. P. (1993). Commitment processes in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,10, 175–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/026540759301000202.

Rusu, P. P., Hilpert, P., Beach, S. H., Turliuc, M. N., & Bodenmann, G. (2015). Dyadic coping mediates the association of sanctification with marital satisfaction and well-being. Journal of Family Psychology,29, 843–849. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000108.

Seedall, R., Houghtaling, A., & Wilkins, E. (2013). Disclosing extra-dyadic involvement (EDI): Understanding attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Contemporary Family Therapy,35, 745–759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-013-9243-9.

Selterman, D., & Koleva, S. (2015). Moral judgment of close relationship behaviors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,32, 922–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407514554513.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods,7, 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422.

South, S., & Lloyd, K. M. (1995). Spousal alternatives and marital dissolution. American Sociological Review,60, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096343.

Stafford, L. (2016). Marital sanctity, relationship maintenance, and marital quality. Journal of Family Issues,37, 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13515884.

Stafford, L., David, P., & McPherson, S. (2014). Sanctity of marriage and marital quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,31, 54–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407513486975.

Stanley, S., Trathen, D., McCain, D., & Bryan, M. (1998). A lasting promise: A Christian guide to fighting for your marriage. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Swank, A. B., Mahoney, A., & Pargament, K. I. (2000, August). A sacred trust: Parenting and the spiritual realm. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality,72, 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x.

Tarakeshwar, N., Pargament, K., & Mahoney, A. (2003). Initial development of a measure of religious coping among Hindus. Journal of Community Psychology,31, 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10071.

Thompson, A. E., & O’Sullivan, L. F. (2016). Drawing the line: The development of a comprehensive assessment of infidelity judgments. Journal of Sex Research,53, 910–926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1062840.

Treas, J., & Giesen, D. (2000). Sexual infidelity among married and cohabiting Americans. Journal of Marriage and Family,62, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00048.x.

Treger, S., & Sprecher, S. (2011). The influences of sociosexuality and attachment style on reactions to emotional versus sexual infidelity. Journal of Sex Research,48, 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2010.516845.

Tuttle, J. D., & Davis, S. N. (2015). Religion, infidelity, and divorce: Reexamining the effect of religious behavior on divorce among long-married couples. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage,56, 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2015.1058660.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2014). New census bureau statistics show how young adults today compare with previous generations in neighborhoods nationwide. Retrieved August 30, 2018 from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2014/cb14-219.html

Vail-Smith, K., Whetstone, L. M., & Knox, D. (2010). The illusion of safety in monogamous undergraduate relationships. American Journal of Health Behavior,34, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.34.1.2.

Weaver, A. D., MacKeigan, K. L., & MacDonald, H. A. (2011). Experiences and perceptions of young adults in friends with benefits relationships: A qualitative study. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality,20, 41–53.

Whisman, M. A., Gordon, K. C., & Chatav, Y. (2007). Predicting sexual infidelity in a population-based sample of married individuals. Journal of Family Psychology,21, 320–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.320.

Whisman, M. A., & Snyder, D. K. (2007). Sexual infidelity in a national survey of American women: Differences in prevalence and correlates as a function of method of assessment. Journal of Family Psychology,21, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.147.

Wiederman, M. W., & Hurd, C. (1999). Extradyadic involvement during dating. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,16, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407599162008.

Wiggins, J. D., & Lederer, D. A. (1984). Differential antecedents of infidelity in marriage. American Mental Health Counselors Association Journal,6, 152–161.

Wilkins, A. C., & Dalessandro, C. (2013). Monogamy lite: Cheating, college, and women. Gender and Society,7, 728–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243213483878.

Zinnbauer, B. J., Pargament, K. I., & Scott, A. B. (1999). The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality,67, 889–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00077.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

University IRB approval of methods was obtained before data collection.

Informed Consent

All participants completed an informed consent before participation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McAllister, P., Henderson, E., Maddock, M. et al. Sanctification and Cheating Among Emerging Adults. Arch Sex Behav 49, 1177–1188 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01657-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01657-3