Abstract

Long-term romantic commitments may offer many benefits. It is thus unsurprising that people employ strategies that help protect their relationships against the allure of alternative partners. The present research focused on the circumstances under which these strategies are less effective. Specifically, four studies examined the effect of internal relationship threat on expressions of desire for alternative mates. In Study 1, participants reported perceptions of relationship threat, their desire for their partner, and expressions of attraction to alternative mates. In Studies 2–4, participants underwent a threat manipulation and then encountered attractive strangers. Their reactions during these encounters (expressed interest, provision of help, and overt flirtation in Studies 2, 3, and 4, respectively) were recorded. Results showed that experiencing threat led to increased expressions of desire for alternatives. As indicated in Studies 1 and 2, decreased desire for current partners partially explained this effect, suggesting that desire functions as a gauge of romantic compatibility, ensuring that only valued relationships are maintained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Long-term romantic commitments typically fulfill love and intimacy needs and contribute to personal well-being (e.g., Dush & Amato, 2005). It is therefore of little surprise that people strive to maintain their relationships by employing strategies that help protect them against the allure of alternative partners (Lydon & Karremans, 2015). Unfortunately, such relationship maintenance strategies are not always successful. Indeed, many relationships that were intended to last eventually dissolve, and even within relationships that endure, the rate of infidelity is rather high, with estimates of lifetime engagement in extra-relational affairs ranging from 20 to 70% (e.g., Allen et al., 2005; Atkins, Baucom, & Jacobson, 2001; Blow & Hartnett, 2005; Wiederman & Hurd, 1999).

Research exploring the determinants of infidelity has mainly focused on personality characteristics that make people more prone to engaging in extradyadic affairs (e.g., attachment avoidance, unrestricted sociosexual orientation; DeWall et al., 2011; Mattingly et al., 2011). Relatively less is known about the relationship circumstances that lead people to stray from their current partner and the processes that drive them. The studies that do focus on relational precipitating factors of infidelity have relied on either anecdotal clinical reports or correlational designs (e.g., Allen et al., 2005; Brown, 1991), precluding causal conclusions about the relationship circumstances that encourage extradyadic affairs.

In the present research, we investigated the possibility that experiencing threats that are internal to the relationship and that stem from the partner’s hurtful behavior (e.g., expressing criticism, neglecting a partner’s needs) lessens people’s motivation to protect their relationship from external threats implied by attractive alternatives. In doing so, we relied on evolutionary theorizing to explain that sexual desire has evolved to serve as a means of evaluating partners’ mate value and thus might be diverted to alternative mates when current partners’ behavior indicates relationship incompatibility (Birnbaum, 2018; Buss, Goetz, Duntley, Asao, & Conroy-Beam, 2017). Specifically, we examined whether relationship threat would undermine people’s sexual desire for their current partners, thereby rendering them more vulnerable to feeling attracted to alternative mates and then acting on that attraction.

Sustaining Relationships in the Face of Threat

Individuals in committed relationships often encounter attractive alternative partners. Such encounters activate automatic approach tendencies (van Straaten, Engels, Finkenauer, & Holland, 2009), manifested in the impulse to attend to these people (van Straaten, Holland, Finkenauer, Hollenstein, & Engels, 2010). Of course, paying attention to an attractive person may lead to becoming involved with this person, which, in turn, may damage the current relationship (e.g., Amato & Previti, 2003; Scott, Rhoades, Stanley, Allen, & Markman, 2013). To stay committed to current partners and avoid the negative consequences of straying, people typically enact strategies that inhibit relationship-threatening responses. For example, in contrast to their single counterparts, romantically involved individuals tend to be less attentive to potential alternative partners (e.g., Maner, Rouby, & Gonzaga, 2008), devalue their attractiveness (e.g., Lydon, Fitzsimons, & Naidoo, 2003), and show fewer signs of interest in interacting with them (e.g., mimicking them to a lesser extent; Karremans & Verwijmeren, 2008; Simpson, Gangestad, & Lerma, 1990).

Nevertheless, some risks to couple well-being result from partners’ misdeeds rather than from outside influences (i.e., internal threats). Whereas relatively routine perturbations of romantic life, such as occasional conflicts or signs of a partner’s irritation, can be easily dismissed, more influential relationship threats may undermine the relationship by activating self-protection goals that encourage distancing from the hurtful partner (Cavallo, Fitzsimons, & Holmes, 2010; Murray, Derrick, Leder, & Holmes, 2008). Experiencing doubts about partners’ love leads, for example, to perceiving the relationship as less valuable and hindering expressions of intimacy toward partners (Birnbaum, Simpson, Weisberg, Barnea, & Assulin-Simhon, 2012; Marigold, Holmes, & Ross, 2007). With repeated experience, the ability to protect one’s relationship from such internally threatening events may be eroded, giving rise to negative feelings toward current partners (Jostmann, Karremans, & Finkenauer, 2011). In these cases, partners may find themselves questioning their compatibility and feeling attracted to alternative mates (Buss et al., 2017).

Indeed, although infidelity can occur in well-functioning relationships, there are likely chronic and contextual factors that weaken a relationship and reduce people’s motivation to maintain the relationship (Allen et al., 2005). Anecdotal clinical reports indicate that people endorse relational problems, such as a lack of support or dissatisfaction with sex, as a major reason for their affairs and often attribute the transition from considering the possibility of an affair to actual extradyadic involvement to an acutely distressing relationship event (e.g., Allen et al., 2005; Atwood & Seifer, 1997). Past studies support these reports, showing that low sexual and relationship satisfaction are associated with a greater likelihood of infidelity (e.g., Mark, Janssen, & Milhausen, 2011; Scott et al., 2016). Still, most of these studies are correlational and rely on potentially biased retrospective recall of relational issues that pre-date the extradyadic involvement. Hence, their findings do not allow for causal conclusions.

The Present Research

The present research sought to examine the effect of threats internal to a relationship on coping with the external threat of attractive alternatives and whether lower desire for current partners might help explain this effect. Sexual desire is theorized to function as a visceral gauge of mate desirability, with higher (vs. lower) desire for existing partners inducing greater exertions toward the intensification of romantic relationships with valued partners (Birnbaum, 2018; Birnbaum & Finkel, 2015). As such, sexual desire for one’s existing partner should reflect disruptions caused by the partners’ misdeeds and the resulting changes in their perceived mate value, motivating detachment from less valued partners and the pursuit of more desirable alternatives (Birnbaum, 2018). Accordingly, we predicted that threat that emanates from partner transgressions would dampen the desire for this partner. This lower desire, in turn, should decrease motivation to protect current relationships by inhibiting expressions of interest in alternative partners.

Four studies examined the effect of internal relationship threat on expressions of desire for alternative mates. In Study 1, participants reported perceptions of relationship threat, their desire for their partner, and expressions of attraction to alternative mates. In Studies 2–4, participants underwent an experimental threat manipulation and then encountered attractive strangers. Their reactions during these encounters were recorded (expressed interest, provision of help, and overt flirtation in Studies 2, 3, and 4, respectively). In all studies, all data were collected before any analyses were conducted, and all data exclusions, manipulations, and variables analyzed are reported. Our specific predictions were as follows:

-

1.

Internal relationship threat would lead to increased expressions of desire for attractive alternative partners.

-

2.

Decreased sexual desire for one’s partner would account for the link between relationship threat and desire for alternative partners, such that relationship threat would decrease desire for one’s partner, which, in turn, would predict heightened desire for alternative mates.

Study 1

In Study 1, we examined whether experiencing threat to the relationship would be associated with increased expressions of desire for attractive alternatives and whether decreased sexual desire for one’s current partner would explain this association. We hypothesized that relationship threat would be associated with lower sexual desire for one’s partner, which in turn, would predict greater desire for alternative mates. To test this hypothesis, romantically involved participants completed an online survey in which they indicated the extent to which they had felt hurt and disappointed by their partner lately. They also rated their sexual desire for their partner and the extent to which they had fantasized and flirted with alternative mates recently.

Method

Participants

A total of 310 participants (205 women, 105 men) from a university in central Israel volunteered for the study. Following Fritz and MacKinnon’s (2007) suggestion, sample size was determined via a priori power analysis using PowMedR in R (Kenny, 2013) to ensure 90% power to detect a medium effect size (.30 in a correlation metric; Cohen, 1988) for both paths a and b in a mediation analysis. This hypothesized effect size was based on previous research examining the effects of relationship threat on sexual fantasies (Birnbaum, Svitelman, Bar-Shalom, & Porat, 2008). Potential participants were included in the sample if they were in a steady, heterosexual, and monogamous relationship. Participants ranged from 18 to 65 years of age (M = 28.69, SD = 2.91). All participants were currently involved in a romantic relationship. Relationship length ranged from 1 to 444 months (M = 64.44, SD = 75.86). Sixty-four percent of the participants were cohabiting with their partner and 30% were married. Eighteen percent had children.

Measures and Procedure

Participants who agreed to participate in a study of experiences in romantic relationships were given a link to an online Qualtrics survey. After completing an online consent form, participants were instructed to think about their current romantic relationship and their recent feelings and thoughts about it. Participants then rated their agreement with each statement, using a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much so). Specifically, participants completed four items assessing the extent to which their perceptions of relationship threat (e.g., “My partner has disappointed me”; α = .76); four items assessing their desire for their partner (e.g., “I have felt a great deal of sexual desire for my partner”; α = .88; Birnbaum et al., 2016); and three items assessing expressions of desire for alternative mates (e.g., “I have fantasized sexually about someone who is not my current partner”; “I have flirted with someone who is not my current partner”; α = .88). Finally, they provided basic demographic information (e.g., age, relationship length).

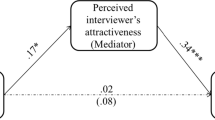

Results and Discussion

To examine whether the association between experiencing relationship threat and expressions of desire for alternative mates was mediated by decreased sexual desire for one’s partner, we used PROCESS (Hayes, 2013, model 4), in which relationship threat was the predictor, desire for alternative mates was the outcome measure, and desire for one’s partner was the mediator. Table 1 presents zero-order correlations and additional descriptive statistics. Figure 1 shows the final model. This analysis revealed a significant association between relationship threat and desire for one’s partner (b = − .41, SE .06, t = − 7.32, p < .001, β = − .39, 95% CI for β = − .49, − .29). The analysis further revealed a significant association between desire for one’s partner and expressions of desire for alternative mates (b = − .56, SE .07, t = − 7.65, p < .001, β = − .40, 95% CI for β = − .50, − .30), such that participants who experienced lower sexual desire for their partner experienced greater desire for alternative mates.

Mediation model showing that sexual desire for one’s partner mediated the association between relationship threat and expressions of desire for alternative mates in Study 1. Note. Path coefficients are standardized. The value in parentheses is from the analysis of the effect without desire for one’s partner in the equation. ***p < .001

Desire for one’s partner was also uniquely associated with desire for alternative mates after controlling for relationship threat (b = − .43, SE .08, t = − 5.59, p < .001, β = − .31, 95% CI for β = − .42, − .20). Finally, results indicated that the 95% CI of the indirect effect for relationship threat as a predictor of expressions of desire for alternative mates through desire for one’s partner did not include zero and thus is considered significant (abcs = .12, b = .18, SE .05, 95% CI for β = .06, .20). Neither gender nor relationship length moderated these associations.

Overall, the analyses indicated that the association between relationship threat and desire for alternative mates was partially mediated by desire for one’s partner, such that experiencing relationship threat was associated with decreased sexual desire for one’s partner, which in turn, predicted more expressions of desire for alternative mates. These findings suggest that inhibiting expressions of desire serves as a mechanism that shields the self from being hurt by partners whose love and commitment is being questioned, and from investing in a relationship whose future is unclear. Previous research has already shown that people react to partner transgression by defensively distancing themselves from the hurtful partner (Cavallo et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2008). Our findings extend this research, indicating that this distancing may be manifested in the sexual realm in the form of thwarted desire. Lower desire for current partners may lessen the motivation to protect the relationship, thereby unleashing desire for alternative, seemingly more promising, mates. Still, because Study 1 was a survey, one cannot rule out the possibility that individuals who experience lower desire for their current partners tend to perceive these partners in a more negative light, viewing them as more hurtful, rather than the other way around. Study 2 addressed this limitation.

Study 2

Because Study 1 was correlational and cross-sectional, we cannot rule out alternative explanations. Study 2 sought to establish a causal connection between experiencing relationship threat and exhibiting more desire for alternative mates. To do so, we employed an experimental design and examined the effect of manipulated levels of relationship threat on derogation of attractive alternatives. Specifically, participants were asked to vividly describe either a time when their romantic partner had hurt them or a typical day in their lives. Then, they rated their sexual desire for their partner and evaluated pictures of attractive opposite-sex others, indicating whether the pictured person might be a potential partner. We counted the number of selected partners to assess attraction toward non-partner targets, with a lower value indicating derogation of alternatives.

Method

Participants

One hundred and thirty students (69 women, 61 men) from a university in central Israel volunteered for the study. Following Fritz and MacKinnon’s (2007) suggestion, sample size was determined via a priori power analysis using PowMedR in R (Kenny, 2013) to ensure 80% power to detect a medium effect size (.30 in a correlation metric) for both paths a and b in a mediation analysis. We strived to ensure 80% power rather than 90% power as in Study 1 because recruitment is more challenging in experimental designs involving individual sessions as compared with surveys. Potential participants were included in the sample if they were in a steady, heterosexual, and monogamous relationship of longer than 4 months. Participants ranged from 21 to 38 years of age (M = 26.13, SD = 3.29). Relationship length ranged from 4 to 160 months (M = 29.93, SD = 31.33). No significant differences were found between the experimental conditions for any of the socio-demographic variables.

Measures and Procedure

Participants who agreed to participate in a study of interpersonal perceptions were individually scheduled to attend a single half-hour laboratory session. Prior to each session, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: relationship threat and control. Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants were greeted by a research assistant. Then, following the procedure of Murray et al. (2008), participants in the relationship threat condition were instructed to provide a written description of a time when they had felt intensely disappointed, hurt, or let down by their romantic partner. Participants were instructed to describe both what had happened and how they had felt about the experience at the time in detail. Participants in the control condition were asked to describe a typical day in their lives from morning to night.

After describing their experiences, participants completed two items assessing their perceptions of relationship threat (e.g., “To what extent do you feel hurt by your partner when thinking about the experience you described?”; “To what extent do you feel angry with your partner when thinking about the experience you described?”; α = .96). Similar items were used in previous studies examining the effects of relationship threats (vs. control conditions) on various sexual expressions (Birnbaum et al., 2008; Birnbaum, Weisberg, & Simpson, 2011). None of the participants in the control condition expressed difficulties in understanding or answering these items. Participants also completed three of the items assessing their sexual desire for their partner, used in Study 1 (e.g., “I feel a great deal of sexual desire for my partner”; α = .89; Birnbaum et al., 2016). Ratings were made on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much so).

To assess derogation of attractive alternatives, we followed the procedure of Ritter, Karremans, and van Schie (2010) and instructed participants to evaluate pictures of 20 attractive and 20 unattractive opposite-sex others. These pictures were taken from a pilot study, in which pictures of women and men were evaluated by opposite-sex others. For each sex, 20 pictures with the lowest mean and 20 pictures with the highest mean were chosen for the present research. The pictures were presented in a randomized order. Participants were instructed to indicate within 800 ms, by pressing the “yes” or “no” button, whether the pictured person might be a potential partner (“Do you consider this person to be a potential partner, irrespective of your current relationship status?”). This time pressure was applied to make sure that participants had little opportunity to control their judgment by exerting self-regulation. Participants’ yes responses were coded as 1 and their no responses as 0. The sum of these values indicates the number of attractive non-partner targets that were selected as potential partners; derogation of alternatives is indicated by a lower value. Finally, participants were asked to provide demographic information and were then fully debriefed.

Results and Discussion

Manipulation Check

A t test on perceptions of relationship threat yielded the expected effect, t(128) = 16.85, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 2.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) for Cohen’s d [2.45, 3.45]. Participants reported significantly greater threat to their relationship in the threat condition (M = 4.49, SD = 1.68) than in the control condition (M = 1.02, SD = .09).

The Effect of Threat on Attraction toward Opposite-Sex Others

To examine whether the effect of manipulated relationship threat on interest in alternative mates was mediated by decreased sexual desire for one’s partner, we used PROCESS (Hayes, 2013, model 4), in which manipulated threat was the predictor, interest in alternative mates was the outcome measure, and desire for one’s partner was the mediator. Figure 2 shows the final model. This analysis revealed a significant effect of manipulated threat on desire for one’s partner (b = − .46, SE .18, t = − 2.46, p = .015, β = − .21, 95% CI for β = − .37, − .05). The analysis further revealed a significant main effect of desire for one’s partner on interest in alternative mates (b = − .89, SE .38, t = − 2.30, p = .023, β = − .20, 95% CI for β = − .36, − .04), such that participants who experienced lower sexual desire for their partner expressed greater interest in alternative mates.

Mediation model showing that sexual desire for one’s partner mediated the effect of relationship threat on interest in alternative mates in Study 2. Note. Path coefficients are standardized. The value in parentheses is from the analysis of the effect without desire for one’s partner in the equation. #p < .10; *p < .05

Desire for one’s partner was also uniquely associated with interest in alternative mates after controlling for manipulated threat (b = − .77, SE .39, t = − 1.97, p = .050, β = − .17, 95% CI for β = − .33, − .01). Finally, results indicated that the 95% CI of the indirect effect for manipulated threat as a predictor of interest in alternative mates through desire for one’s partner did not include zero and thus is considered significant (abcs = .04, b = .35, SE .21, 95% CI for β = .01, .09). Hence, the analyses support the hypothesized effect, such that experiencing relationship threat decreased sexual desire for one’s partner, which in turn, predicted greater interest in alternative mates.

These findings are the first to establish a causal link between facing relationship threats and experiencing lower sexual desire for current partners, along with heightened approach tendencies toward attractive alternative mates. The finding that desire for current partners was decreased by signs of partner incompatibility supports the theorizing that desire is sensitive to variations in partner’s mate value, encouraging switching from the current, less suitable partner to potentially more beneficial mates (Birnbaum, 2018; Buss et al., 2017). And yet, the approach motivation exhibited in this study in response to threat might not necessarily translate into approach behavior. Moreover, it is possible that the approach tendencies aroused by threat are motivated by general social motives, such as the need for belonging or the need to feel good about oneself, rather than by mate pursuit per se. Study 3 explored these possibilities.

Study 3

Study 2 showed that experiencing internal relationship threat increased interest in attractive alternatives. In Study 3, we explored whether the effect of relationship threat on interest in potential alternative mates, which likely indicates approach motivation (Impett et al., 2010; van Straaten et al., 2009), would manifest in observed approach behavior and hold true while interacting with an opposite-sex stranger, but not while interacting with a same-sex stranger (who would not be considered a potential mate, which therefore controls for other possible motives that could enhance approach tendencies). For this purpose, we crossed the threat manipulation used in Study 2 with the confederate’s gender. This resulted in a 2 (threat) × 2 (confederate’s gender) design, such that participants underwent a relationship threat manipulation and then interacted with either same-sex or opposite-sex confederates who ostensibly sought their help. Participants’ helping behaviors toward the confederate (duration and quality of help) were recorded.

We focused on the tendency to help an attractive stranger in need for two reasons: First, because we wanted a behavioral measure of approach motivation. Second, because provision of help may function as a relationship-initiating strategy (Bell & Daly, 1984) that is likely to seem more appropriate under the circumstances of a laboratory experiment than overt flirting and thus as a less risky channel for expressing interest in alternative partners. We hypothesized that confederate’s gender would moderate the effect of threat on provision of help, such that participants would provide more help to an opposite-sex confederate than to a same-sex confederate in the threat condition but not in the control condition.

Method

Participants

Two hundred students (104 women, 96 men) from a university in central Israel participated in the study for course credit or in exchange for $12. Sample size was determined via a priori power analysis using the G*Power software package (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009) to ensure 80% power to detect a medium effect size, f, of 0.25 at p < .05. Potential participants were included in the sample if they were in a steady, heterosexual, and monogamous relationship of longer than 4 months. We discovered retrospectively that 10 participants (8 women, 2 men) lied about their relationship status to get course credits and therefore excluded them. Participants ranged from 19 to 32 years of age (M = 24.38, SD = 2.03). Relationship length ranged from 4 to 120 months (M = 30.12, SD = 24.52). No significant differences were found between the experimental conditions for any of the socio-demographic variables.

Measures and Procedure

Participants who agreed to participate in a study of interpersonal and cognitive skills were individually scheduled to attend a single half-hour laboratory session. Similarly to Study 2, participants were greeted by an experimenter and were randomly assigned to describe either a time when their current partner had hurt them or their typical commute to campus. After describing their experiences, participants completed three items assessing their perceptions of relationship threat. Two of the items were similar to those used in Study 2. The third item explicitly assessed feelings of threat (“To what extent does the event you have just described arouse in you feelings of threat?”; α = .79). Ratings were made on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much so). Following the manipulation, participants were led to believe that in the next 5 min they and another participant would complete a questionnaire assessing their verbal reasoning. In reality, all participants were assigned an attractive same-sex or opposite-sex confederate who was blind to the experimental condition. The confederates’ attractiveness was assessed prior to participating in the study. The experimenter then introduced the confederate to the participants, seated them next to each other, told both that they were allowed to speak with each other while completing the questionnaire, and left the room.

When the confederate ostensibly got to the third question (approximately 2 min after the experimenter had left the room), he or she turned to the participants and asked their help in solving that question, uttering, “I’m stuck with this question. Could you please help me in solving it?” Participants’ helping behaviors toward the confederate were recorded, using the following measures: The actual time spent helping solving the needed question (in seconds), which was measured using a stopwatch hidden in the confederates’ pocket, and the quality of the given help, as assessed by five items, which were completed by the confederate following this session (e.g., “To what extent was the participant helpful?”; “To what extent was the help effective?”; α = .92). Ratings were made on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much so). After 5 min, the experimenter returned to the room and asked the participants to stop working on the questionnaire. Participants then provided demographic information and were fully debriefed.

Results and Discussion

Manipulation Check

A t test on perceptions of relationship threat yielded the expected effect, t(188) = 16.35, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 2.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) for Cohen’s d [2.03, 2.79]. Participants experienced greater threat to their relationship in the threat condition (M = 3.16, SD = .87) than in the control condition (M = 1.35, SD = .52).

The Effect of Threat on Provision of Help to Same-Sex and Opposite-Sex Strangers

To examine the hypothesized effect of threat and confederates’ gender on duration and quality of help, we conducted two 2 (threat) × 2 (gender pairing) analysis of variance (ANOVA). Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and statistics for this analysis. A two-way ANOVA examining the effects of threat and confederates’ gender on quality of help indicated that the effect of gender pairing was significant, F(1, 186) = 5.58, p = .019, η 2 p = .029, such that the quality of help was higher when participants helped an opposite-sex confederate (M = 3.51, SD = 1.19) than when they helped a same-sex confederate (M = 3.14, SD = 1.27). This effect was marginally moderated by threat, F(1, 186) = 3.60, p = .057, η 2 p = .019. Simple effects tests revealed that in the control condition, gender pairing had no significant effect, F(1, 186) = .13, p = .717, η 2 p = .001; however, in the threat condition, gender pairing had a significant effect on quality of help, F(1, 186) = 7.70, p = .006, η 2 p = .040.

A two-way ANOVA examining the effects of threat and confederates’ gender on duration of help showed that the effect of gender pairing was significant, F(1, 186) = 13.08, p < .001, η 2 p = .066, such that the duration of help was longer when participants helped an opposite-sex confederate (M = 45.68, SD = 29.97) than when they helped a same-sex confederate (M = 32.85, SD = 20.80). The interaction between threat and confederates’ gender was not significant (p = .15, see Table 2). Still, because significance is not a necessary condition for testing orthogonal, planned comparisons (Gonzalez, 2008), we conducted simple effect tests. These tests showed that in the control condition, gender pairing had no significant effect, F(1, 186) = 2.85, p = .093, η 2 p = .015; however, in the threat condition, the confederates’ gender had a significant effect on quality of help, F(1, 186) = 10.90, p < .001, η 2 p = .055.

Overall, the findings indicate that participants invested more time and effort in providing help to an attractive opposite-sex stranger in need than to a same-sex stranger. This tendency to provide better and more help to an opposite-sex stranger emerged only under relationship threat. Hence, it is unlikely that provision of help was motivated by purely prosocial needs or by the desire to feel better to relieve the aversive experience of threat. Rather, it seems that people used the prosocial route to strategically approach a desired mate (Bell & Daly, 1984). In all likelihood, provision of help is perceived as a more legitimate and less awkward channel for approaching a stranger than overt flirting, particularly for people who claim to be in a monogamous relationship.

Study 4

Study 3 showed that experiencing internal relationship threat encouraged provision of help to an attractive opposite-sex stranger. Although helping a stranger in need may serve as a relationship-initiating strategy (Bell & Daly, 1984), the meaning it conveys is not as clear as that of overt flirting. Study 4 addressed this limitation by examining whether relationship threat would lead to actual flirtation with an attractive opposite-sex stranger. For this purpose, we experimentally manipulated relationship threat by instructing participants to describe either a time when their current partner had hurt them or a typical day in their life as a couple. Then, participants were introduced to an attractive opposite-sex confederate who interviewed them about their attitudes toward interpersonal dilemmas while being videotaped. The videotaped interactions were coded for displays of flirtatious behavior toward the confederate interviewer.

Method

Participants

A total of 81 students (45 women, 36 men) from a university in central Israel volunteered for the study without compensation. Originally, we sought a similar number of participants per condition as in Study 2, based on a priori power analysis. However, recruitment difficulties led us to end the study prematurely and we decided to analyze and report the data at that stage. Potential participants were recruited for the sample if they were in a steady, heterosexual, and monogamous relationship of longer than 4 months. Participants ranged from 19 to 44 years of age (M = 23.64, SD = 3.01). Relationship length ranged from 4 to 42 months (M = 10.52, SD = 13.09). No significant differences were found between the experimental conditions for any of the socio-demographic variables.

Measures and Procedure

Participants who agreed to participate in a study of interpersonal experiences and attitudes were individually scheduled to attend a single half-hour laboratory session. Similarly to Study 2, participants were greeted by an experimenter and were randomly assigned to describe either a time when their current partner had hurt them or a typical day in their life as a couple. After describing their experiences, participants completed the two items used in Study 2 to assess their perceptions of relationship threat (α = .90). Ratings were made on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much so).

Following the manipulation, the experimenter told the participants that they would be interviewed by a research assistant to evaluate their attitudes toward interpersonal dilemmas. In fact, all participants were assigned an attractive opposite-sex confederate interviewer whose attractiveness was assessed prior to participating in the study. The confederates were blind to the experimental condition and were trained to respond in a manner that conveyed contact readiness, exhibiting behaviors that signal warmth and immediacy (e.g., close physical proximity, frequent eye contact; Andersen, 1985; Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989; Leck & Simpson, 1999), to facilitate approach motivation. The experimenter introduced the interviewer to the participants and left the room.

The interviewer started the interview by asking a set of standard questions about participants’ hobbies, positive traits, and future career plans, designed to make the participants feel comfortable. The interviewer then told participants that they were about to discuss several interpersonal dilemmas. To ensure consistency across experimental conditions, the interviewer used a fixed interview script, in which participants were asked to give their opinion on interpersonal dilemmas (e.g., “Are you for or against playing ‘hard to get’ at the start of a relationship?”). All interviews, which lasted 5–7 min, were videotaped by two cameras mounted in the corners of the room, with one camera pointed at each interlocutor at an angle to allow for full frontal recording. After the interview, participants were asked to provide demographic information and were then fully debriefed.

Coding Flirtatious Behavior toward the Confederate Interviewer

The video-recorded interviews were coded by two trained independent judges (psychology students) who were blind to the hypotheses and to the experimental condition. Each judge watched the interviews and rated each participant’s overt nonverbal expressions of flirtatious behavior (e.g., flashing seductive smiles, exchanges of penetrating gaze, petting one’s body, and cocking head to one side) in a single overall behavioral coding of displays of flirtatious behavior. This coding scheme has been used successfully in previous studies (Birnbaum, Mikulincer, Szepsenwol, Shaver, & Mizrahi, 2014; Birnbaum et al., 2016; Mizrahi, Hirschberger, Mikulincer, Szepsenwol, & Birnbaum, 2016). The judges also coded participants’ expressions of uneasiness about being interviewed (e.g., frozen facial expressions, fidgeting, fiddling with fingers, speaking timidly). Ratings were made on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Inter-rater reliability was high: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for flirtatious behavior and expressions of uneasiness were 0.76 and 0.85, respectively. Hence, judges’ ratings were averaged for each participant.

Results and Discussion

Manipulation Check

A t test on perceptions of relationship threat yielded the expected effect, t(79) = 16.47, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 3.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) for Cohen’s d [2.94, 4.37]. Participants reported greater threat to their relationship in the threat condition (M = 4.20, SD = 1.06) than in the control condition (M = 1.22, SD = .42).

The Effect of Threat on Flirtatious Behavior toward the Interviewer

A t test on displays of flirtatious behavior yielded the expected effect, t(79) = 2.01, p = .048, Cohen’s d = 0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) for Cohen’s d [0.01, 0.89]. Participants exhibited more flirtatious behavior in the threat condition (M = 2.83, SD = .71) than in the control condition (M = 2.48, SD = .85). As expected, a t test on displays of uneasiness during the interview did not yield a significant effect, t(79) = .82, p = .415, Cohen’s d = 0.18, 95% CI for Cohen’s d [− 0.25, 0.62]. Expressions of uneasiness were not significantly different in the threat condition (M = 2.02, SD = .91) than in the control condition (M = 2.19, SD = .95), indicating that relationship threat led to flirtatious behavior toward an attractive stranger but did not affect participants’ general uneasiness about the circumstances.

Overall, Study 4 replicated the findings of Studies 1–3 and extended them by showing that experiencing a threat to a current relationship is manifested not only in approach tendencies but also in overt flirting with an attractive stranger, as can be observed by judges. By doing so, Study 4 ruled out other possible motives that could enhance approach tendencies or a motivated construal process explanation (Reis & Gable, 2000), indicating that one partner’s hurtful behavior may push the other partner closer to becoming involved in an extradyadic affair.

Meta-Analysis of Studies 2–4

To examine overall patterns in the effects found, we conducted a fixed-effects weighted means meta-analysis, using Hedges’s optimal weights for meta-analysis, as recommended by Lipsey and Wilson (2001). Specifically, we used the meta-analytic spreadsheet tool provided by Braver, Thoemmes, and Rosenthal (2014), which calculates the overall meta-analytic effect size after weighting each effect by the inverse of its variance (i.e., the inverse of the squared standard error of the difference in means), so that the more precisely estimated effects have a stronger influence on the aggregated effect size. In Study 3, we calculated the effect size d for each DV and then averaged the ds across DVs. We report the results of Hedges’ g (which is calculated by the spreadsheet tool) as the primary standardized effect size for mean differences because g controls for bias due to small samples. Overall, participants exhibited greater expressions of desire for alternative mates in the threat condition than in the control condition, Hedges’ g = .37, SE .12, z = 3.12, p < .001, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.59]. Thus, although Study 4 was underpowered, combining the data from the three experiments indicated that the effect of threat on expressions of desire for alternative mates should be considered reliable.

General Discussion

Throughout their romantic life, people will almost inevitably encounter threats to the bond with their partner which arise both within and outside their relationship. Scholars have described several relationship-promoting responses for healing the resulting hurts, such as forgiveness or other intimacy-enhancing acts (e.g., Bono, McCullough, & Root, 2008; Karremans & Van Lange, 2004). And yet, people often respond to relationship threats by defensively distancing themselves from their partner rather than by employing these relationship-promoting strategies (Cavallo et al., 2010; Murray et al., 2008). The present research indicates that when threats internal to a relationship arise, partners may become more vulnerable to feeling attracted to, and flirting with, potential alternative partners. This attraction may interfere with their ability or willingness to engage in relationship-promoting behavior.

More specifically, in four studies, we showed that experiencing relationship threat, which emanated from recollection of current partners’ misdeeds, led to increased expressions of desire for attractive alternative mates and that lower desire for current partners explained this effect. Study 1 found that experiencing relationship threat was associated with lesser sexual desire for one’s partner, which in turn, predicted more expressions of desire for alternative mates (e.g., extradyadic sexual fantasies). Study 2 replicated and extended these findings by establishing a causal connection between recollecting relationship threats and experiencing lower sexual desire for current partners, along with heightened interest in attractive alternative mates. Study 3 indicated that relationship threat not only induced interest in alternative mates but was also manifested in observed approach behavior toward them, as demonstrated by provision of help to an attractive stranger in need. Study 4 added to these findings by showing that experiencing a threat to the current relationship led to overt flirting with an attractive stranger.

These findings extend previous results in several ways. First, studies that investigated the relational antecedents of infidelity have relied either on anecdotal clinical reports or on correlational designs and therefore do not support causal interpretations (Allen et al., 2005, Blow & Hartnett, 2005). Second, previous studies were based on self-reported experiences of infidelity rather than observed displays of actual flirtation (e.g., Mark et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2016). By including two studies that examined actual behavior, we can rule out motivated construal processes as an explanation for our findings, which self-report studies cannot do (Reis & Gable, 2000). Third, prior research has not identified the mechanisms underlying the link between relationship threat and expressions of desire for alternative mates.

Past studies have indicated that even people who are normally inclined to trust their partners might reduce dependence on them under relationship-threatening circumstances (e.g., Murray et al. 2008). Our research adds to these studies by showing that such defensive distancing may be manifested in lesser desire for one’s partner, which, in turn, releases inhibition on feeling and expressing attraction to potential alternative mates. These findings support the idea that sexual desire functions to ensure that valued relationships are maintained, leaving relationships that fail to satisfy emotional needs more susceptible to outside influences (Birnbaum, 2018; Birnbaum & Finkel, 2015). Indeed, feeling sexually attracted to alternative partners may provide a means for partners to overcome their feelings of hurt.

It remains unclear, however, how the threat–desire dynamic unfolds over time and whether relationship fragility in this context would translate into actual involvement in extradyadic affairs. To be sure, sexual desire is not the only force that holds partners together. Many other psychological processes affect relationship quality and longevity (e.g., interdependence, investment, commitment, trust; Berscheid & Regan, 2005; Finkel, Simpson, & Eastwick, 2017; Reis, Collins, & Berscheid, 2000), some of which are likely to drive the level of sexual desire between partners (Birnbaum, 2018). Flirting with attractive potential mates, thus, does not necessarily mean that people will actually become sexually involved with them (and break up with their current partner). Future studies should employ experimental and longitudinal designs to explore how competing processes (e.g., commitment, forgiveness, revenge) interact under various threats to predict relationship stability and well-being in the long run.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our research is the first to establish a causal link between experiencing internal relationship threats and approach behavior toward attractive alternative mates. In doing so, our research indicates that partners’ hurtful behavior diminishes the desire for these partners, directing attention, at least momentarily, to new, seemingly more promising relationships. Overall, the findings underscore the dual potential of sexual desire for both relationship promotion and deterioration, supporting theorizing that proposes that sexual desire evolved to serve a dual function, namely either to deepen a current valued relationship or to promote a new relationship when the existing relationship has become less rewarding and improvement seems unlikely (Birnbaum, 2018).

Further research is needed to determine when and how attraction to alternative partners may hinder, or at times even help, relationship repair. For example, it would be useful to investigate the emotions that help regulate desire for alternative mates (e.g., feeling excitement vs. guilt) and determine whether intimates will act on their desire or inhibit it. Similarly, from an interventionist perspective, it would also be valuable to determine whether the implementation of educational program that raise awareness of the circumstances that make committed relationships more fragile (e.g., stressful environment, key transitions that occur during relationship development, circumstances in which self-control is decreased) can help improve coping with the allure of alternative mates.

References

Allen, E. S., Atkins, D. C., Baucom, D. H., Snyder, D. K., Gordon, K. C., & Glass, S. P. (2005). Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual factors in engaging in and responding to extramarital involvement. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12, 101–130.

Amato, P. R., & Previti, D. (2003). People’s reasons for divorcing: Gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. Journal of Family Issues, 24, 602–626.

Andersen, P. A. (1985). Nonverbal immediacy in interpersonal communication. In A. W. Siegman & S. Feldstein (Eds.), Multichannel integrations of nonverbal behavior (pp. 1–36). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Atkins, D. C., Baucom, D. H., & Jacobson, N. S. (2001). Understanding infidelity: Correlates in a national random sample. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(4), 735–749.

Atwood, J. D., & Seifer, M. (1997). Extramarital affairs and constructed meanings: A social constructionist therapeutic approach. American Journal of Family Therapy, 25, 55–74.

Bell, R. A., & Daly, J. A. (1984). The affinity-seeking function of communication. Communication Monographs, 51, 91–115.

Berscheid, E., & Regan, P. C. (2005). The psychology of interpersonal relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Birnbaum, G. E. (2018). The fragile spell of desire: A functional perspective on changes in sexual desire across relationship development. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(2), 101–127.

Birnbaum, G. E., & Finkel, E. J. (2015). The magnetism that holds us together: Sexuality and relationship maintenance across relationship development. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 29–33.

Birnbaum, G. E., Mikulincer, M., Szepsenwol, O., Shaver, P. R., & Mizrahi, M. (2014). When sex goes wrong: A behavioral systems perspective on individual differences in sexual attitudes, motives, feelings, and behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 822–842.

Birnbaum, G. E., Reis, H. T., Mizrahi, M., Kanat-Maymon, Y., Sass, O., & Granovski-Milner, C. (2016). Intimately connected: The importance of partner responsiveness for experiencing sexual desire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 530–546.

Birnbaum, G. E., Simpson, J. A., Weisberg, Y. J., Barnea, E., & Assulin-Simhon, Z. (2012). Is it my overactive imagination? The effects of contextually activated attachment insecurity on sexual fantasies. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29, 1131–1152.

Birnbaum, G. E., Svitelman, N., Bar-Shalom, A., & Porat, O. (2008). The thin line between reality and imagination: Attachment orientations and the effects of relationship threats on sexual fantasies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1185–1199.

Birnbaum, G. E., Weisberg, Y. J., & Simpson, J. A. (2011). Desire under attack: Attachment orientations and the effects of relationship threat on sexual motivations. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28, 448–468.

Blow, A. J., & Hartnett, K. (2005). Infidelity in committed relationships II: A substantive review. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 31, 217–233.

Bono, G., McCullough, M. E., & Root, L. M. (2008). Forgiveness, feeling connected to others, and well-being: Two longitudinal studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 182–195.

Braver, S., Thoemmes, F., & Rosenthal, B. (2014). Cumulative meta-analysis and replicability. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 333–342.

Brown, E. M. (1991). Patterns of infidelity and their treatment. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Buss, D. M., Goetz, C., Duntley, J. D., Asao, K., & Conroy-Beam, D. (2017). The mate switching hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 143–149.

Cavallo, J. V., Fitzsimons, G. M., & Holmes, J. G. (2010). When self-protection overreaches: Relationship-specific threat activates domain-general avoidance motivation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 1–8.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Academic Press.

DeWall, C., Lambert, N., Slotter, E., Pond, R., Deckman, T., Finkel, E., … Fincham, F. (2011). So far away from one’s partner, yet so close to romantic alternatives: Avoidant attachment, interest in alternatives, and infidelity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 1302–1316.

Dush, C. M. K., & Amato, P. R. (2005). Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(5), 607–627.

Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. (1989). Human ethology. New York: de Gruyter.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160.

Finkel, E. J., Simpson, J. A., & Eastwick, P. W. (2017). The psychology of close relationships: Fourteen core principles. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 4.1–4.29.

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18, 233–239.

Gonzalez, R. (2008). Data analysis for experimental design. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Impett, E. A., Gordon, A. M., Kogan, A., Oveis, C., Gable, S. L., & Keltner, D. (2010). Moving toward more perfect unions: Daily and long-term consequences of approach and avoidance goals in romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 948–963.

Jostmann, N. B., Karremans, J., & Finkenauer, C. (2011). When love is not blind: Rumination impairs implicit affect regulation in response to romantic relationship threat. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 506–518.

Karremans, J. C., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2004). Back to caring after being hurt: The role of forgiveness. European Journal of Social Psychology, 34, 207–227.

Karremans, J. C., & Verwijmeren, T. (2008). Mimicking attractive opposite-sex others: The role of romantic relationship status. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 939–950.

Kenny, D. (2013). PowMedR. R program to compute power of joint test for continuous exposure, mediator, and outcome. Retrieved December 16, 2015 from http://davidakenny.net/progs/PowMedR.txt.

Leck, K., & Simpson, J. (1999). Feigning romantic interest: The role of self-monitoring. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(1), 69–91.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lydon, J. E., Fitzsimons, G. M., & Naidoo, L. (2003). Devaluation versus enhancement of attractive alternatives: A critical test using the calibration paradigm. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 349–359.

Lydon, J., & Karremans, J. C. (2015). Relationship regulation in the face of eye candy: A motivated cognition framework for understanding responses to attractive alternatives. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 76–80.

Maner, J. K., Rouby, D. A., & Gonzaga, G. C. (2008). Automatic inattention to attractive alternatives: The evolved psychology of relationship maintenance. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29, 343–349.

Marigold, D. C., Holmes, J. G., & Ross, M. (2007). More than words: Reframing compliments from romantic partners fosters security in low self-esteem individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 232–248.

Mark, K. P., Janssen, E., & Milhausen, R. R. (2011). Infidelity in heterosexual couples: Demographic, interpersonal, and personality-related predictors of extradyadic sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(5), 971–982.

Mattingly, B. A., Clark, E. M., Weidler, D. J., Bullock, M., Hackathorn, J., & Blankmeyer, K. (2011). Sociosexual orientation, commitment, and infidelity: A mediation analysis. Journal of Social Psychology, 151, 222–226.

Mizrahi, M., Hirschberger, G., Mikulincer, M., Szepsenwol, O., & Birnbaum, G. E. (2016). Reassuring sex: Can sexual desire and intimacy reduce relationship-specific attachment insecurities? European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(4), 467–480.

Murray, S. L., Derrick, J. L., Leder, S., & Holmes, J. G. (2008). Balancing connectedness and self-protection goals in close relationships: A levels-of-processing perspective on risk regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(3), 429–459.

Reis, H. T., Collins, W. A., & Berscheid, E. (2000). The relationship context of human behavior and development. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 844–872.

Reis, H. T., & Gable, S. L. (2000). Event-sampling and other methods for studying everyday experience. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 190–222). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ritter, S. M., Karremans, J. C., & van Schie, H. T. (2010). The role of self-regulation in derogating attractive alternatives. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(4), 631–637.

Scott, S. B., Parsons, A., Post, K. M., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., & Rhoades, G. K. (2016). Changes in the sexual relationship and relationship adjustment precede extradyadic sexual involvement. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(2), 395–406.

Scott, S. B., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., Allen, E. S., & Markman, H. J. (2013). Reasons for divorce and recollections of premarital intervention: Implications for improving relationship education. Couple & Family Psychology, 2(2), 131–145.

Simpson, J. A., Gangestad, S. W., & Lerma, M. (1990). Perception of physical attractiveness: Mechanisms involved in the maintenance of romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1192–1201.

van Straaten, I., Engels, R. C. M. E., Finkenauer, C., & Holland, R. W. (2009). Meeting your match: How attractiveness similarity affects approach behavior in mixed-sex dyads. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 685–697.

van Straaten, I., Holland, R. W., Finkenauer, C., Hollenstein, T., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2010). Gazing behavior during mixed-sex interactions: Sex and attractiveness effects. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 1055–1062.

Wiederman, M. W., & Hurd, C. (1999). Extradyadic involvement during dating. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16(2), 265–274.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bat Primo, May Barbi, Taqwa Jaljolie, and Maya Davidovich for their assistance in the collection of the data and Kobi Zholtack, Romi Orr, Danelle Izakov, Gil Tsessler, Shiran Arinus, Oz Klein, and Ron Lerner for their assistance in conducting the research. This research was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (Grants 86/10 and 1210/16 awarded to Gurit E. Birnbaum) and by the Binational Science Foundation (Grants #2011381 and #2016405 awarded to Gurit E. Birnbaum and Harry T. Reis).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All study procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, prior to data collection.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Birnbaum, G.E., Mizrahi, M., Kovler, L. et al. Our Fragile Relationships: Relationship Threat and Its Effect on the Allure of Alternative Mates. Arch Sex Behav 48, 703–713 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1321-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1321-5