Abstract

The direct link between stigma against sexual minorities and psychological distress is well established. However, few studies have examined the potential mediating roles of avoidant and social support coping in the relationships between internalized and anticipated stigma associated with homosexuality and depressive symptoms and anxiety among Chinese men who have sex with men (MSM). We recruited a longitudinal sample of 493 MSM in Beijing, China from 2011 to 2012. Participants completed computer-based questionnaires at baseline, 6, and 12 months. We found significant indirect effects of anticipated MSM stigma on symptoms of both depression and anxiety via avoidant coping: anticipated MSM stigma at baseline was significantly associated with avoidant coping (B = 0.523, p < 0.001) at 6 months and, conditional on anticipated MSM stigma, avoidant coping had a significant positive effect on depressive symptoms and anxiety at 12 months (B = 0.069, p = 0.001 and B = 0.071, p = 0.014). In contrast, no significant indirect effects of anticipated MSM stigma on either psychological distress outcome via social support coping were found. No significant indirect effects of internalized MSM stigma via either avoidant or social support coping were found. These results underscore the need for interventions that address anticipations of stigma and the use of avoidant coping techniques to manage such anticipations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although homosexuality in China has not been subject to the same degree of persecution as in other countries, it was stigmatized because of the society’s emphasis on procreation and social order (Liu et al., 2006; Zhang, Li, Li, & Beck, 1999). With the enactment of the “open-door” policy of the late 1970s and the resulting economic and social changes, same-sex attraction and behavior has become increasingly visible and subject to fewer formal sanctions (Liu et al., 2006; Zhang & Chu, 2005). Gay communities began forming in major urban areas in the mid-1990s and then quickly developed in medium-size cities (Zhang & Chu, 2005). Same-gender sex was decriminalized in 1997 and removed as a psychiatric condition by the Chinese Psychiatric Association in 2001 (Liu et al., 2006; Zhang & Chu, 2005). Nonetheless, homosexual behavior remains subject to prejudice because it continues to be seen by many as a rejection of China’s cultural tradition to marry and have children (Li, 1998; Liu & Choi, 2006; Zhang & Chu, 2005). Yang and Kleinman (2008) have highlighted the important role that reciprocity plays in the development and continuance of social relationships in China. They noted that stigma leads to a loss of face, defined as the embodiment of social power in interpersonal interactions (Hwang, 1987). A condition or behavior that is seen as morally contaminating will limit a person’s ability to participate fully in social life. This in turn can result in rejection by family members who seek to avoid being stigmatized by association, and encourages avoidance of activities that may lead to the discovery of the stigmatized condition (Yang & Kleinman, 2008).

Indeed, recent research suggests that experiences of stigma and discrimination based on sexual orientation continue to be prevalent among Chinese men who have sex with men (MSM) (Feng, Wu, & Detels, 2010; He et al., 2006; Liu & Choi, 2006; Liu & Choi, 2013; Steward, Miege, & Choi, 2013). A study of MSM in Shanghai found that 97 % of respondents reported having ever perceived some stigma in their lifetime (e.g., having heard that homosexual people are not normal) (Liu & Choi, 2013). Moreover, almost one quarter of the sample in this study reported lifetime experiences of discrimination based on sexual orientation, such as physical violence and losing friends, a job, or housing. In line with the observations of Yang and Kleinman (2008) research has also shown how reciprocal social obligations, particularly those related to a son’s duty to his parents, play out in MSM’s life decisions and opinions about ethical responsibilities. Men differ in whether they consider it more ethically responsible to forgo marriage to avoid emotionally hurting a female partner or opting for marriage in order to avoid bringing shame on their parents (Steward et al., 2013). This research and other studies suggest that the pressures tied to maintaining face and harmony within the family are associated with stress and internalized feelings of blame and low self-worth (Steward et al., 2013; Zang, Guida, Sun, & Liu, 2014).

Minority stress theory (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003) has been proposed to explain the well-documented, disproportionate prevalence of various mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety disorders, and suicide attempts, among sexual minorities (King et al., 2008). According to this theory, individuals from stigmatized social groups are exposed to excess stress and experience mental health difficulties due to their minority status (Meyer, 1995, 2003). The sources of minority stress are conceptualized as violence and discrimination, anticipations of rejection and discrimination, and internalized homophobia (internalization of negative attitudes toward sexual minorities). The theory further posits that coping with stigma can ameliorate the negative effects of minority stress on mental health outcomes.

Empirical studies have demonstrated that various forms of sexual stigma (e.g., experiences of anti-gay violence and discrimination (Choi, Paul, Ayala, Boylan, & Gregorich, 2013; Herek, Gillis, & Cogan, 1999; Hershberger & D’Augelli, 1995; Meyer, 1995; Mills et al., 2004; Otis & Skinner, 1996; Szymanski, 2009; Waldo, 1999), anticipations of rejection and discrimination (Chae & Yoshikawa, 2008; Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Erickson, 2008; Lewis, Derlega, Griffin, & Krowinski, 2003; Meyer, 1995; Yoshikawa, Wilson, Chae, & Cheng, 2004), and internalized homophobia (McGregor, Carver, Antoni, Weiss, & Yount, 2001; Meyer, 1995; Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008; Szymanski & Owens, 2008; Szymanski & Sung, 2010; Talley & Bettencourt, 2011) are associated with poor mental health outcomes among sexual minorities, supporting minority stress hypotheses (Meyer, 2003). However, the role of coping in the link between sexual stigma and psychological distress is less clear. A study of U.S. gay men and lesbians found that problem-solving coping (actions taken to change the source of stress) and avoidant coping (disengagement from stigma-related stressors) moderated the association between internalized homophobia and psychological distress (Talley & Bettencourt, 2011). In a study of U.S. MSM, social support was identified as a buffer against the detrimental effects of minority stress (e.g., racism, homophobia) on depressive symptoms (Wong, Schrager, Holloway, Meyer, & Kipke, 2014). However, no such moderating effects (altering the strength of the association between stigma and distress) were found in studies that examined internalized homophobia among U.S. lesbians (Szymanski & Owens, 2008) and experiences of discrimination among U.S. gay and bisexual men (Szymanski, 2009). Moreover, some evidence suggests that coping responses to stigma may serve instead as mediators (the mechanisms through which sexual stigma influences mental health outcomes) (Szymanski & Owens, 2008). Studies conducted with U.S. lesbian and bisexual women demonstrated that internalized homophobia was positively associated with avoidant coping and social support, which, in turn, led to greater psychological distress (Szymanski & Kashubeck-West, 2008; Szymanski & Owens, 2008). Moreover, the causal direction of associations among sexual stigma, coping, and psychological distress found in prior research remains poorly understood because of the cross-sectional nature of the past work.

Although the experiences of sexual stigma among MSM in China are well documented (Feng et al., 2010; Liu & Choi, 2006, 2013; Steward et al., 2013), little is known about their impact on psychological well-being among Chinese MSM. Prior studies of Chinese MSM have focused on describing the experienced stigma (Feng et al., 2010; Liu & Choi, 2006; Steward et al., 2013), assessing the validity and reliability of stigma scales (Hu et al., 2014; Liu, Feng, Rhodes, & Liu, 2009; Neilands, Steward, & Choi, 2008), or investigating the impact of stigma on HIV risk (Choi, Hudes, & Steward, 2008; Liu et al., 2011). Also, few studies have explored the potential moderating and mediating roles of coping styles in the relationship between sexual stigma and psychological distress among these men.

The present study aims to expand the literature by investigating the influence of sexual stigma and coping on mental health outcomes in a longitudinal cohort of 493 MSM recruited in Beijing, China. Specifically, this study examines two common forms of sexual stigma experienced by Chinese MSM, internalization of negative attitudes toward MSM (to be referred as internalized MSM stigma) and anticipations of discrimination against MSM (to be referred as anticipated MSM stigma), and their associations with two forms of psychological distress: depression and anxiety. It investigates whether avoidant coping and social support coping (a kind of problem-solving coping as an attempt to gain control over a stigma-related stressor) mediate the effects of internalized and anticipated MSM stigma on depressive symptoms and anxiety, and whether the relationships between the two forms of coping and the two forms of psychological distress (depressive symptoms and anxiety) are moderated by stigma. Clarification of these roles will provide information needed to determine targets (e.g., either sexual stigma or coping styles; both sexual stigma and coping styles) of interventions designed to reduce the negative impact of sexual stigma on psychological well-being. Also, unlike prior studies that relied on cross-sectional data, our longitudinal design helps to disambiguate the direction of causal effects.

Method

Participants

Data came from the Beijing Men’s Health Study. This study was a longitudinal survey designed to identify the specific mechanisms by which MSM stigma affects sexual risk behaviors among MSM in China. Study participants were recruited in Beijing from June 2011 to September 2012. A snowball sample of participants was recruited through referrals from colleagues working in governmental and non-governmental organizations that served the MSM community in Beijing, as well as referrals from enrolled participants. In addition, peer recruiters approached men in MSM-identified venues (e.g., public parks, toilets, brothels). Men were eligible for the study if they were 18 years old or older, lived in Beijing, reported having ever engaged in same-gender sex, and had not participated in the previous phases of this study that involved qualitative interviews (Steward et al., 2013) and survey instrument pretesting. Eligible individuals were asked to schedule a time to participate at our study site at Beijing Normal University.

Procedure

During their scheduled study appointment, men first verified their eligibility and provided written informed consent. We then asked the participants to supply one or more means of contacting them for follow-up wave participation. Potential forms of contact included telephone numbers, email addresses, QQ addresses (a social media platform popular in China), and postal addresses. Participants most typically provided a cell phone number and/or a QQ account. The men then completed a 45-minute, standardized questionnaire using audio computer-assisted, self-interviewing (ACASI) technology. The survey questions were initially developed in English and then translated to Chinese by collaborators fluent in both English and Chinese. The survey was designed so that men could complete it by themselves using a desktop computer in the study office. If a participant desired, he was able to listen to a computer-generated voice read each of the questions and answer options in Mandarin Chinese. Study investigators were located in a nearby location and available to answer questions about the survey if men had them.

After completing the survey, participants received 100 yuan (approximately $15) for compensation and were scheduled to return to the study site 6 and 12 months later to complete follow-up, ACASI-based surveys similar to the one employed at baseline. They were also asked to refer their friends and acquaintances to the study. Prior to each scheduled date for follow-up wave participation, men were contacted via the information they had provided to remind them of the study. We continued to contact the men twice weekly up to a total of 14 contact attempts if they did not show up for a follow-up survey. Those who completed 6- and 12-month assessments received 100 yuan for each assessment (200 yuan in total). If they completed all three assessments, they received an additional 50 yuan after completing 12-month assessments.

The study was approved by the Committee for Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Social Development and Public Policy at Beijing Normal University.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

Respondents were asked about their age, education, marital status, sexual orientation, and Beijing residence status (i.e., having a legal permit to live in the city with a hukou card).

MSM Stigma

We measured two different forms of MSM stigma: internalized and anticipated MSM stigma. Internalized MSM stigma assessed respondents’ own stigmatizing views. This construct was measured using a 15-item scale adapted from prior work with HIV-positive people in India (Steward et al., 2008) and based on the kinds of beliefs reported by Beijing MSM in an earlier qualitative phase of the project (Steward et al., 2013) (e.g., “I look down on gay men”; “I believe homosexuality is an abnormality”; Cronbach’s α = .84). Anticipated MSM stigma assessed respondents’ expectations of discriminatory behaviors from others (e.g., parents, friends, coworkers, doctors). This construct was measured using an 18-item scale (e.g., “My parents would not talk to me if I told them that I am gay”; “I would not be able to advance in my work unit if I told my coworkers that I am gay”; Cronbach’s α = .92). It was adapted from anticipated stigma measures that had been used in other countries (Wolfe et al., 2008) and based on the kinds of anticipatory stigma concerns reported by Beijing MSM in an earlier phase of the project (Steward et al., 2013). Responses to individual items for both stigma measures were captured on a six-point ordinal response set scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). Responses were averaged to create internalized and anticipated MSM stigma scale scores with a possible range from 1 to 6, where higher scores reflected greater stigma.

Coping Styles

We assessed two types of coping: avoidant and social support coping. Avoidant coping was measured by adapting the Avoidance subscale of the Identity Management Strategies Scale developed by Button (2004). This five-item measure assessed respondents’ withdrawals from stigmatizing situations (e.g., “I avoid situations [e.g., dinner, parties] where my family members are likely to ask me personal questions”; “I avoid coworkers who frequently discuss sexual matters”; Cronbach’s α = .86). Social support coping was measured with three items assessing the perceived availability of social support specific to the experiences of MSM stigma (i.e., “When I feel treated unfairly or discriminated against because of my sexual orientation, there are family members I can rely on to be there for me”; “When I feel treated unfairly or discriminated against because of my sexual orientation, there are straight friends I can rely on to be there for me”; “When I feel treated unfairly or discriminated against because of my sexual orientation, there are gay friends I can rely on to be there for me”; Cronbach’s α = .78). Reponses to items on both coping measures were recorded using the same six-point ordinal response set: 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Scores were averaged across each set of items to form the avoidant and social support coping scales, with higher scores reflecting greater use of a particular form of coping.

Psychological Distress

We assessed two forms of psychological distress: depressive symptomatology and anxiety. Depressive symptoms were measured by the 20-item, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Mirowsky & Ross, 1992). The CES-D asked about the number of days respondents experienced each of the 20 depressive symptoms in the previous week (e.g., feeling lonely, feeling sad; Cronbach’s α = .90). Answers were noted using a four-point response set (1 = less than one day to 4 = 5–7 days). Anxiety was measured with the six-item Anxiety subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 1983). This scale asked about the level of discomfort respondents felt about each of six anxious states in the previous week (e.g., feeling fearful, spells of terror or panic; Cronbach’s α = .93). Answers were provided using a five-point response set (0 = no discomfort to 4 = extreme discomfort). Responses were averaged to create the depression and anxiety scale scores, with higher scores representing greater levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety.

Statistical Analysis

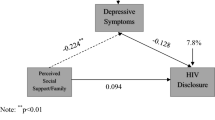

We conducted path analyses via a series of linear regression models to examine the potential mediating roles of the two coping styles assessed at 6 months (avoidant and social support coping) on the effects of two baseline stigma measures (anticipated and internalized stigma) on two 12-month psychological distress outcomes (depressive symptoms and anxiety), after controlling for age (treated as a continuous variable), Beijing residence card (hukou), education, marital status, and self-reported sexual orientation. In other words, four indirect effects were tested: 2 coping measures by 2 psychological distress outcomes (see Fig. 1). Regression models of each outcome simultaneously considered the effects of both MSM stigma as well as both coping style measures. The so-called “joint test” was used to determine the significance level of each indirect effect (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). As a further assessment of mediation, we tested whether each stigma measure modified the effect of each coping measure on each psychological distress outcome (Kraemer, Kiernan, Essex, & Kupfer, 2008).

Indirect effects of anticipated and internalized MSM stigma on psychological distress via avoidant and social support coping. a Direct effect of stigma on depressive symptoms (the total effects of anticipated and internalized MSM stigma on depressive symptoms were 0.053 and −0.008, respectively); b direct effect of stigma on anxiety symptoms; (the total effects of anticipated and internalized MSM stigma on anxiety symptoms were 0.086* and −0.019, respectively); c effect of coping on depressive symptoms; d effect of coping on anxiety symptoms. All models controlled for age, education, marital status, sexual orientation, and having a Beijing hukou; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Results

Of 523 men screened, 493 met eligibility criteria and completed baseline assessments. Of these 493 participants, 410 (83 %) and 416 (84 %) returned for 6- and 12-month assessments, respectively. The most common reasons for being lost to follow-up at a wave were an inability to reach the men via the contact information they had supplied or because the men reported that they were no longer living in Beijing. The participants who had a high school education or more or who had a Beijing hukou were more likely to return for the two assessments compared to those who had no high school education or no Beijing hukou (p < 0.05).

Table 1 reports sample characteristics for 455 participants who completed baseline interviews and reported being HIV-negative at baseline. Their mean age was 30 years old (range, 18–73). Close to half (49 %) of these men had a high school diploma or less and the other half had either some college education (9 %), a 2-year college degree (18 %), or a 4-year college degree (24 %). More than three quarters (77 %) were never married, 14 % were currently married to a woman, and 9 % were separated, divorced or widowed. A majority self-identified as gay (70 %) or bisexual (24 %). Only 20 % had a Beijing hukou.

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson product-moment correlations for internalized and anticipated MSM stigma at baseline, avoidant and social support coping at 6 months, and depressive symptoms and anxiety at 12 months. Internalized MSM stigma at baseline was not correlated with either depressive symptoms or anxiety at 12 months. It was positively associated with avoidant coping at 6 months, but not with social support coping at 6 months. By contrast, anticipated MSM stigma at baseline was positively associated with both depressive symptoms and anxiety at 12 months, as well as positively associated with both avoidant and social support coping at 6 months. Avoidant coping at 6 months was positively associated with both depressive symptoms and anxiety at 12 months, whereas social support coping at 6 months was negatively associated with only depressive symptoms at 12 months.

In path modeling, anticipated MSM stigma at baseline was significantly associated with avoidant coping at 6 months (B = 0.523, p < 0.0001) and avoidant coping at 6 months, in turn, was significantly associated with symptoms of depression (B = 0.069, p = 0.001) and anxiety at 12 months (B = 0.071, p = 0.014; Fig. 1). Thus, by the joint test, significant indirect effects of anticipated stigma, via avoidant coping, were found for both psychological distress outcomes. In contrast, anticipated MSM stigma at baseline was not significantly associated with social support coping at 6 months (B = 0.117, p = 0.173), suggesting that social support coping did not significantly mediate the effects of anticipated MSM stigma on either psychological distress outcome. Even so, social support coping at 6 months was significantly associated with depressive symptoms at 12 months (B = −0.056, p = 0.004), but not with anxiety at 12 months (B = −0.024, p = 0.354). Finally, the total and direct effects of anticipated MSM stigma at baseline on both psychological distress outcomes at 12 months were non-significant.

Internalized MSM stigma at baseline was not significantly associated with the two candidate mediators describing avoidant or social support coping at 6 months, nor with the outcomes describing symptoms of depression or anxiety at 12 months. That is, all modeled total, direct, and indirect effects of internalized stigma were non-significant (Fig. 1).

Discussion

This study examined the potential mediating role of avoidant and social support coping in the associations between two forms of MSM stigma (internalized, anticipated) and two forms of psychological distress (depressive symptoms, anxiety) in a longitudinal sample of MSM in China. Initial bivariate correlations revealed that anticipated stigma, but not internalized stigma, was directly associated with both depressive symptoms and anxiety. Subsequent multivariate analyses demonstrated that avoidant coping, but not social support coping, mediated the associations between anticipated MSM stigma and both psychological distress measures, and that once these indirect effects were accounted for, there was no direct association between anticipate stigma and psychological distress.

These findings are important because they stand in contrast to prior research. First, they point to a stronger association between anticipations of stigma and psychological distress than between internalizations of stigma and distress. Findings from other parts of the world suggest a more prominent role for internalized stigma (Anderson, Ross, Nyoni, & McCurdy, 2015; Herrick et al., 2013; Lea, de Wit, & Reynolds, 2014; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Wong et al., 2014) in shaping MSM’s mental health. Second, our results differ from prior research because they point to a larger role for avoidant coping, instead of social support coping, in shaping men’s mental well-being. Prior work on minority stress theory (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003) and other empirical studies (Wong et al., 2014) found that social support helps buffer against the negative effects of sexual minority stress on psychological well-being. Our data, by contrast, suggest that avoidant coping is the pathway by which stigma exerts its impact on psychological distress.

We do not have sufficient data to draw definitive conclusions about why our findings with Chinese MSM differ from research in other settings. However, prior work points to potential explanations. The experience of stigma in China is intertwined with the concept of losing face, which itself is built upon the importance of reciprocity in the maintenance of social relationships (Yang & Kleinman, 2008). MSM stigma strips a man of his moral standing within interactions and poses challenges to fulfilling expectations of reciprocity, particularly those that relate to repaying parents by marrying a woman and having children who carry on the family name (Li, 1998; Liu & Choi, 2006; Zhang & Chu, 2005). Liu and colleagues demonstrated that these cultural dynamics influence the kinds of stigma concerns of greatest salience to Chinese MSM (Liu et al., 2011). Men who focus more attention on individual success (e.g., trying to do things better than others) report relatively higher levels of internalized stigma. By contrast, those who focus more attention on collective success (e.g., willing to give up personal pursuits to take care of family) report higher levels of felt stigma. (Anticipated stigma and felt stigma are similar constructs.) An earlier, qualitative phase of our own work is also instructive. In interviews, MSM repeatedly referred back to their filial duties to parents when explaining their reasons for avoiding disclosure of same-sex behaviors (Steward et al., 2013). Even those who had disclosed their sexual orientation to parents and described themselves as accepting of their same-sex attractions still spoke of feeling pressure to honor their parents through culturally normative acts like marriage to a woman (Steward et al., 2013).

Taken together, these earlier data suggest that a more collectivist focus on fulfilling one’s duty to parents places attention on how one is being perceived by others (anticipated stigma). In turn, that focus logically leads to behaviors that seek to control information about same-sex attractions (e.g., avoidant coping), which are seen as running counter to filial duties to marry and carry on the family name. And because acts of reciprocity are so central to the Chinese social organizational structure, it is challenging for men to fully mitigate the psychological impact of not fulfilling their expected role as a son, even when they have elicited degrees of support from family and friends (i.e., decreased role for social support coping).

The current findings suggest that interventions to address the impact of stigma on Chinese MSM’s mental well-being need to focus on both anticipations of stigma and the use of avoidant coping techniques to manage such anticipations. In doing so, it will be important to acknowledge that interventions cannot necessarily change the state of the environment in which men live. Stigma against MSM is rooted in strongly engrained traditions in China that place a premium on sons marrying and having children (Li, 1998; Liu & Choi, 2006; Zhang & Chu, 2005). But, at the same time, there is concern about the rising incidence of HIV among MSM (Li et al., 2011), and increasing interest in combination programs that increase condom use and help to connect HIV-infected men to care (Lou et al., 2014). The avoidant coping strategies used to manage anticipations of stigma can encompass delays in seeking testing and care (Yang & Kleinman, 2008). Addressing them could help respond to a pressing public health challenge, and thus offers a window of opportunity that might not otherwise be available. Although MSM may not always be able to change the prejudicial attitudes and discrimination that exist (which is what makes avoidance of situations where stigma is anticipated an effective means of coping in the first place), it may be feasible to help them more realistically assess when such anticipations are warranted. For those situations where stigma is reasonably anticipated, it may also be possible to guide men toward coping strategies that allow them to remain productively engaged in the situation without needing to avoid it altogether. These steps, although not eliminating stigma altogether, would reduce the likelihood of men experiencing depression or anxiety and may also contribute to other public health objectives, such as increased engagement with HIV testing and care.

Our study has certain limitations that should be kept in mind. First, it was conducted exclusively in Beijing and we cannot know whether the results generalize to other parts of the country. Second, the sample was relatively young. This may reflect generational changes in how homosexuality is perceived. It is possible that older men’s conceptualization of homosexuality differs, which in turn could affect the ways in which they perceive anti-MSM stigma and manage it. Third, a primary reason men were lost to follow-up was our inability to reach them again. It is possible, if not likely, that this problem was in part a byproduct of stigma. The most frequently supplied forms of contact information were cell phone numbers and QQ account, both of which are relatively anonymous. Participants were often unwilling to supply information like a postal address that can be more readily linked back to a person’s name. If a participant was extremely worried about being identified as taking part in a study on MSM, he might have been motivated to supply faulty contact information so that there would be nothing in the study records that could be linked to him. If so, this would mean that we were relatively more likely to lose those individuals with the highest levels of anticipated stigma. Fourth, the surveys at all three waves used similar questions. It is possible that participants’ responses may have been influenced by their experience in prior waves. It should be noted, however, that the survey measures of relevance to the data we report here were ones that did not have a design that would intrinsically favor one set of responses over another (in the context of longer surveys, this can come, for example, in the form of a reduced set of items if a person answers questions a particular way). The stigma, coping, and mental health assessments were always of equal length regardless of the answers that a person gave. Fifth and finally, our measures were assessed in survey waves spaced 6 months apart. This is a relatively long spacing, particularly for mental health outcomes that are typically assessed using recall periods focused only on the prior few weeks. That we were able to detect effects with this design may well be a testament to the strength and enduring nature of the relationships. However, it also is possible that some of the nuance in the relationships was lost given the long lag times between waves.

Conclusions

Stigma can have profound effects on MSM. Our findings suggest that anticipations of stigma are particularly influential on men’s mental health, and that avoidant coping strategies amplify the association between stigma and psychological distress. These results align with prior research that points to the importance in Chinese society of maintaining reciprocity in relationships and to how stigma causes a person to lose face. The social consequences of stigma place an emphasis on guarding against loss of social status by avoiding circumstances in which a stigmatized attribute is made salient. Future research needs to develop interventions that help men limit anticipations of stigma to situations where such concerns are truly warranted, and to develop coping strategies that reduce men’s reliance on avoidance as a way of managing stigma.

References

Anderson, A. M., Ross, M. W., Nyoni, J. E., & McCurdy, S. A. (2015). High prevalence of stigma-related abuse among a sample of men who have sex with men in Tanzania: Implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care, 27(1), 63–70.

Brooks, V. (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Lexington, KY: Lexington Press.

Button, S. B. (2004). Identity management strategies utilized by lesbian and gay employees. Group and Organization Management, 29(4), 470–494.

Chae, D. H., & Yoshikawa, H. (2008). Perceived group devaluation, depression, and HIV-risk behavior among Asian gay men. Health Psychology, 27(2), 140–148.

Choi, K., Hudes, E. S., & Steward, W. T. (2008). Social discrimination, concurrent sexual partnerships, and HIV risk among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. AIDS Behavior, 12(4 Suppl.), S71–77.

Choi, K., Paul, J., Ayala, G., Boylan, R., & Gregorich, S. E. (2013). Experiences of discrimination and their impact on the mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 868–874.

Derogatis, L. M. (1983). Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Reports, 13, 595–605.

Diaz, R. M., Ayala, G., Bein, E., Henne, J., & Marin, B. V. (2001). The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 927–932.

Feng, Y., Wu, Z., & Detels, R. (2010). Evolution of men who have sex with men community and experienced stigma among men who have sex with men in Chengdu, China. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 53(Suppl. 1), S98–S103.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Erickson, S. J. (2008). Minority stress predictors of HIV risk behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms: Results from a prospective study of bereaved gay men. Health Psychology, 27(4), 455–462.

He, Q., Wang, Y., Lin, P., Liu, Y., Yang, F., Fu, X., & Li, Y. (2006). Potential bridges for HIV infection to men who have sex with men in Guangzhou, China. AIDS and Behavior, 10, S17–S23.

Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (1999). Psychological sequelae of hate-crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(6), 945–951.

Herrick, A. L., Stall, R., Chmiel, J. S., Guadamuz, T. E., Penniman, T., Shoptaw, S., … Plankey, M. W. (2013). It gets better: Resolution of internalized homophobia over time and associations with positive health outcomes among MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 17(4), 1423–1430.

Hershberger, S. L., & D’Augelli, A. R. (1995). The impact of victimization on the mental-health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 65–74.

Hu, Y., Lu, H., Raymond, H. F., Sun, Y., Sun, J., Jia, Y., … Ruan, Y. (2014). Measures of condom and safer sex social norms and stigma towards HIV/AIDS among Beijing MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 18(6), 1068–1074.

Hwang, K. K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92, 944–974.

King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 70.

Kraemer, H. C., Kiernan, M., Essex, M., & Kupfer, D. J. (2008). How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychology, 27(2 Suppl.), S101–108.

Lea, T., de Wit, J., & Reynolds, R. (2014). Minority stress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults in Australia: Associations with psychological distress, suicidality, and substance use. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(8), 1571–1578.

Lewis, R. J., Derlega, V. J., Griffin, J. L., & Krowinski, A. C. (2003). Stressors for gay men and lesbians: Life stress, gay-related stress, stigma consciousness, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 22(6), 716–729.

Li, H. M., Peng, R. R., Li, J., Yin, Y. P., Wang, B., Cohen, M. S., & Chen, X. S. (2011). HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in China: A meta-analysis of published studies. PLoS One, 6(8), e23431.

Li, Y. (1998). Subculture of homosexuality. Beijing, China: China Today Press.

Liu, H., Feng, T., Ha, T., Liu, H., Cai, Y., Liu, X., & Li, J. (2011). Chinese culture, homosexuality stigma, social support and condom use: A path analytic model. Stigma Research and Action, 1(1), 27–35.

Liu, H., Feng, T., Rhodes, A. G., & Liu, H. (2009). Assessment of the Chinese version of HIV and homosexuality related stigma scales. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85(1), 65–69.

Liu, H., Yang, H., Li, X., Wang, N., Liu, H., Wang, B., … Stanton, B. (2006). Men who have sex with men and human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted disease control in China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 33(2), 68–76.

Liu, J. X., & Choi, K. (2006). Experiences of social discrimination among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. AIDS and Behavior, 10(4 Suppl.), S25–33.

Liu, J. X., & Choi, K. (2013). Emerging gay identities in China: The prevalence and predictors of social discrimination against men who have sex with men. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Stigma, discrimination and living with HIV/AIDS (pp. 271–287). New York: Springer.

Lou, J., Blevins, M., Ruan, Y., Vermund, S. H., Tang, S., Webb, G. F., … Qian, H. Z. (2014). Modeling the impact on HIV incidence of combination prevention strategies among men who have sex with men in Beijing, China. PLoS One, 9(3), e90985.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104.

McGregor, B., Carver, C., Antoni, M., Weiss, S., & Yount, S. I. G. (2001). Distress and internalized homophobia among lesbian women treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25(1), 1–9.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Mills, T. C., Paul, J., Stall, R., Pollack, L., Canchola, J., Chang, Y. J., … Catania, J. A. (2004). Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The Urban Men’s Health Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(2), 278–285.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1992). Age and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33(3), 187–205.

Neilands, T. B., Steward, W. T., & Choi, K. (2008). Assessment of stigma towards homosexuality in China: A study of men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(5), 838–844.

Newcomb, M. E., & Mustanski, B. (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalized mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 1019–1029.

Otis, M., & Skinner, W. (1996). The prevalence of victimization and its effect on mental well-being among lesbian and gay people. Journal of Homosexuality, 30, 93–122.

Steward, W. T., Herek, G. M., Ramakrishna, J., Bharat, S., Chandy, S., Wrubel, J., & Ekstrand, M. L. (2008). HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Social Science and Medicine, 67(8), 1225–1235.

Steward, W. T., Miege, P., & Choi, K. (2013). Charting a moral life: The influence of stigma and filial duties on marital decisions among Chinese men who have sex with men. PLoS One, 8(8), e71778.

Szymanski, D. M. (2009). Examining potential moderators of the link between heterosexist events and gay and bisexual men’s psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 142–151.

Szymanski, D. M., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2008). Mediators of the relationship between internalized oppressions and lesbian and bisexual women’s psychological distress. Counseling Psychologist, 36, 575–594.

Szymanski, D. M., & Owens, G. P. (2008). Do coping styles moderate or mediate the relationship between internalized heterosexism and sexual minority women’s psychological distress? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(1), 95–104.

Szymanski, D. M., & Sung, M. R. (2010). Minority stress and psychological distress among Asian American sexual minority persons. The Counseling Psychologist, 38(6), 848–872.

Talley, A. E., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2011). The moderator roles of coping style and identity disclosure in the relationship between perceived sexual stigma and psychological distress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(12), 2883–2903.

Waldo, C. R. (1999). Working in a majority context: A structural model of heterosexism as minority stress in the workplace. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46(2), 218–232.

Wolfe, W. R., Weiser, S. D., Leiter, K., Steward, W. T., Percy-de Korte, F., Phaladze, N., … Heisler, M. (2008). The impact of universal access to antiretroviral therapy on HIV stigma in Botswana. American Journal of Public Health, 98(10), 1865–1871.

Wong, C. F., Schrager, S. M., Holloway, I. W., Meyer, I. H., & Kipke, M. D. (2014). Minority stress experiences and psychological well-being: The impact of support from and connection to social networks within the Los Angeles House and Ball communities. Prevention Science, 15(1), 44–55.

Yang, L. H., & Kleinman, A. (2008). ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Social Science and Medicine, 67(3), 398–408.

Yoshikawa, H., Wilson, P. A., Chae, D. H., & Cheng, J. F. (2004). Do family and friendship networks protect against the influence of discrimination on mental health and HIV risk among Asian and Pacific Islander gay men? AIDS Education and Prevention, 16(1), 84–100.

Zang, C., Guida, J., Sun, Y., & Liu, H. (2014). Collectivism culture, HIV stigma and social network support in Anhui, China: A path analytic model. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 28(8), 452–458.

Zhang, B., & Chu, Q. (2005). MSM and HIV/AIDS in China. Cell Research, 15, 858–864.

Zhang, K., Li, D., Li, H., & Beck, E. J. (1999). Changing sexual attitudes and behaviour in China: Implications for the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS Care, 11(5), 581–589.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH085581.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, KH., Steward, W.T., Miège, P. et al. Sexual Stigma, Coping Styles, and Psychological Distress: A Longitudinal Study of Men Who Have Sex With Men in Beijing, China. Arch Sex Behav 45, 1483–1491 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0640-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0640-z