Abstract

Little is known about non-monosexual women’s sexual arousal and desire. Typically, bisexual women have been excluded from research on sexual arousal and desire, whereas mostly heterosexual and mostly lesbian women have been placed into monosexual categories. This research (1) compared the subjective sexual arousal and desire of self-identified heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly lesbian, and lesbian women in partnered sexual activities with men and with women, and (2) compared within-group differences for subjective sexual arousal and desire with men versus women for the five groups. Participants included 388 women (M age = 24.40, SD = 6.40, 188 heterosexual, 53 mostly heterosexual, 64 bisexual, 32 mostly lesbian, 51 lesbian) who filled out the Sexual Arousal and Desire Inventory (SADI). Sexual orientation was associated with sexual arousal and desire in sexual activities with both men and with women. Bisexuals reported higher sexual arousal and desire for women than heterosexuals and lesbians, while lesbians reported lower sexual arousal and desire with men than the other groups. Heterosexuals and mostly heterosexuals scored higher on the male than on the female motivational dimension of the SADI, while the reverse was found for lesbians and mostly lesbians. Findings indicate that non-monosexuals have higher sexual arousal and desire in sexual activities with women than monosexuals. Further, bisexual women did not differentiate their sexual arousal with men versus women, while the other sexual orientation groups differentiated in terms of their motivation to engage in sexual activity. These findings may have implications for how female sexual orientation is conceptualized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Little is known scientifically about the sexual arousal and desire of women who do not subscribe to a monosexual orientation. In general, physiological studies have included only heterosexual and/or lesbian women (Bossio, Suschinsky, Puts, & Chivers, 2014; Chivers, 2010; Chivers & Bailey, 2005, 2007; Chivers, Rieger, Latty, & Bailey, 2004; Chivers, Seto, & Blanchard, 2007; Chivers, Seto, Lalumière, Laan, & Grimbos, 2010; Chivers & Timmers, 2012; Laan, Sonderman, & Janssen, 1995; Suschinsky & Lalumière, 2012; Suschinsky, Lalumière, & Chivers, 2009). A major finding of these studies is that heterosexual women’s genital arousal, as measured by vaginal plethysmography, is not category-specific but can be activated by a variety of erotic stimuli that depict both heterosexual and lesbian themes. In short, heterosexual women’s physiological arousal appears more bisexual than monosexual (Bailey, 2009).

Findings for heterosexual women’s category-specificity regarding subjective sexual arousal are mixed (Chivers & Bailey, 2005; Chivers et al., 2004, 2007). For instance, Chivers et al. (2004) found that heterosexual women’s subjective sexual arousal was higher to erotic films featuring female–male intercourse than to female–female intercourse. However, in another study, they reported higher arousal to female than to male stimuli, indicating lack of category-specificity (Chivers et al., 2007). It is still unclear why heterosexual women would report greater subjective arousal to female than to male stimuli. As pointed out by Chivers et al. (2007): “Further research is needed on the appraisal and meaning of sexual stimuli and on the relationship between these cognitive processes and physiological sexual response [for women] (p. 1117). Research has also assessed the concordance between physiological and subjective measures of sexual arousal in these women. A meta-analysis by Chivers et al. (2010) revealed that for women overall, this relationship is positive but small (Pearson r = .26). Thus, vaginal arousal may be a poor predictor of self-reported sexual arousal and orientation, at least for heterosexual women (Bailey, 2009).

Some studies have indicated that lesbian women may be more category-specific than heterosexual women, both in terms of subjective and genital sexual arousal (Bailey, 2009; Chivers et al., 2004, 2007). For instance, Chivers et al. (2004) found that lesbian women reported the highest subjective sexual arousal to erotic stimuli featuring only women, a finding which was replicated in Chivers et al. (2007). Further, although lesbian women tend to display non-specific genital arousal, they may do so to a lesser extent than heterosexual women (Chivers et al., 2004, 2007). For example, Chivers et al. (2004) documented that while heterosexual women showed the same level of genital arousal to erotic videos depicting male–male couples, female–female couples, and male–female couples, lesbian women were slightly, although not significantly, more aroused genitally by female–female stimuli compared to male–male stimuli. Further, in contrast to heterosexual women, lesbian women show significantly greater genital arousal to stimuli featuring nude women exercising and masturbating than to the same stimuli featuring men (Chivers et al., 2007). Of note, lesbian women’s category-specificity may vary by the explicitness of the sexual stimuli presented. As for heterosexual women, their genital arousal is non-specific in response to stimuli featuring intercourse (Chivers et al., 2007). In sum, the specificity of female sexual arousal may be related to sexual orientation (Chivers, 2010), and specifically to a contrast of sexual experiences that lesbians have had relative to heterosexual women (e.g., conscious awareness of greater arousal to female sex-related cues than to male sex-related cues).

Self-identified bisexual women have typically been excluded from sexual psychophysiology studies. As an example, Chivers et al. (2007) wrote that they “opted to exclude […] women who reported equal sexual attraction to both genders to maximize the clarity of the research design with respect to the category-specificity of gender preferences” (p. 1112). In contrast, “mostly heterosexual” and “mostly lesbian” women, who may represent distinct sexual orientation categories (Savin-Williams & Vrangalova, 2013; Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012), have generally been included with heterosexuals and lesbians, respectively (Chivers & Bailey, 2005; Chivers et al., 2004, 2007; Suschinsky et al., 2009). In short, the notable lack of physiological research including non-monosexual women has been linked to scientists’ preference for methodological and conceptual clarity (Savin-Williams & Vrangalova, 2013; van Anders, 2012).

Although no conclusions may be drawn about the specificity of non-monosexual women’s sexual arousal based on findings from sexual psychophysiology, some research using non-genital measures of sexual interest suggests that bisexual women’s response patterns may differ from their lesbian and heterosexual counterparts. Two viewing-time studies have compared heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women’s category-specificity (Ebsworth & Lalumière, 2012; Lippa, 2013). Both of these studies found that bisexual women displayed bisexual patterns of sexual interest; they looked equally long at pictures of men and of women and rated the images similarly. In contrast, findings were more mixed for the heterosexual women. Whereas they looked longer at pictures of men than of women and rated them as more attractive in the study by Lippa (2013), they displayed non-specificity in the study by Ebsworth and Lalumière (2012; see Israel and Strassberg, 2009, for a similar finding). The lesbian women, as in other viewing-time research (Rullo, Strassberg, & Israel, 2010), looked longer at pictures of women than of men and rated them as more appealing, indicating a greater degree of category-specificity. In short, although women’s genital arousal may be non-specific, other aspects of their sexual orientation may be category-specific, especially for bisexual and lesbian women.

Even if sexual orientation has typically been conceptualized as a combination of attraction (desire), sexual behavior and pleasure, identity, nature of romantic relationships, and physiological arousal (Bailey, 2009; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Mustanski, Chivers, & Bailey, 2002), there is evidence to suggest that these separate dimensions may not necessarily overlap or predict each other (Diamond, 2008b; Lhomond, Saurel-Cubizolles, Michaels, & The CSF Group, 2014; Savin-Williams, 2006, 2009). As noted previously, women’s genital arousal does not necessarily correspond with their self-reported sexual orientation, which suggests that female genital responding is flexible (see Baumeister, 2000, for a review). Further, researchers have not yet reached a consensus on how to best define or measure female sexual orientation (Diamond, 2003b; Mustanski et al., 2002; Savin-Williams 2006, 2009; Savin-Williams & Vrangalova, 2013; Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012). Based on sexual psychophysiology findings, Bailey (2009) raised the question: “Whether anything sexually orients women” (p. 61), whereas Diamond (2003b) asked: “What does sexual orientation orient?”

Despite there being no definite agreement on how to assess female bisexuality, past research measuring women’s self-reported attractions to men and women has, nevertheless, tended to adopt a proportional approach, meaning that participants have been asked to rate their percentage of attractions for women relative to men (Diamond, 1998, 2000, 2003a, 2005, 2008a, b). Although this uni-dimensional methodology may be valid (Rust, 1992), it is possible some women report both high (or low) same-sex and other-sex attractions (Shively & De Cecco, 1977; Storms, 1980; Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012). For instance, one recent study found support for the notion that same-sex and other-sex attractions are not necessarily inversely related. It was concluded “Although traditionally the one-dimensional approach has been favored when assessing sexual orientation, we suggest that the two-dimensional model is a better fit to individual lives” (Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012, p. 97).

Some research has suggested that high sex drive is associated with both male and female bisexuality (Lippa, 2006, 2007). Sex drive, a hypothetical construct, is typically considered to be a reflection of sexual attitudes, behavior, and desire (Baumeister, 2000). Lippa (2006, p. 46) has called it “a generalized energizer of sexual behaviors.” In a series of studies, Lippa (2006, 2007) has found that for most women (lesbians may be an exception), high sex drive is positively correlated with attraction to both men and to women (supporting the hypothesis that attraction may be bi-dimensional). Further, in that study, bisexual women reported higher general sex drive than both lesbian and heterosexual women. If there is indeed a link between non-monosexuality and higher sex drive, then one would expect there to be greater similarity between the sexual arousal and desire of mostly heterosexual, mostly lesbian, and bisexual women than between any of these groups and either lesbians or heterosexuals.

The current research had three goals. The first was to examine similarities and differences in the subjective sexual arousal and desire of heterosexual, bisexual, and lesbian women engendered by partnered sexual activity. Due to the general lack of research investigating the sexual arousal and desire of non-monosexual women, women of five sexual orientation groups were included, along with their subjective ratings of sexual arousal and desire in partnered sexual activities with men and with women. Based on Lippa’s (2006, 2007) findings, we expected that the non-monosexual women would rate their sexual arousal and desire higher than the monosexual women. The second goal was to compare subjective sexual arousal and desire for sexual contact with men versus women for participants in the five sexual orientation groups who reported a history of sexual contact with both men and women. Based on the viewing-time research discussed above, we hypothesized that the bisexual women would rate their arousal and desire with men and with women similarly whereas the other groups would not. The third goal was to investigate which dimension(s) of sexual arousal and desire may be more relevant to how women define their sexual orientation. Based on the sexual psychophysiology research reviewed in the introduction, we expected that women who have had sexual contact with both men and women, regardless of their sexual orientation, would not differentiate based on physiological responses but rather on motivational responses.

Method

Participants

Participants were 388 women (M age = 24.40, SD = 6.40, range = 18–66). Of these, 188 (48.5 %) self-defined their sexual orientation as heterosexual, 53 (13.7 %) as mostly heterosexual, 64 (16.5 %) as bisexual, 32 (8.2 %) as mostly lesbian, and 51 (13.1 %) as lesbian. The majority reported English as their first language (63 %), with 17.5 % reporting French, and 19.5 % reporting “other.” Most endorsed English-Canadian as their main cultural affiliation (63 %), 13 % endorsed French-Canadian, and 24 % endorsed “other.” Seventy-five percent of participants were Canadian nationals and most (90 %) were currently living in an urban setting. Most of the participants were from a middle-class background (76 %), while 15 % reported being from a lower class background and 9 % reported being from an upper class background. More than half of the sample reported being non-religious (56.3 %), while 13.4 % were Catholic, 5.7 % were Jewish, 5.2 % were Protestant, and 19.4 % reported religion as “other.” The vast majority of participants (71 %) were students; of the overall sample, 78 % reported having completed or currently completing a college degree, 15 % reported having completed or currently completing a post-graduate degree, and 7 % reported a high-school degree or less.

Procedure

Data for the current study were collected through an online confidential survey developed by the authors, Women’s Experiences of Sexuality and Intimacy. This survey took 1.5 h to complete and included questions about demographics, substance abuse, childhood abuse, sexual orientation, sexual identity, sexual behavior, sexual/romantic/emotional attractions, sexual arousal/desire/orgasm, and symptoms of depression and anxiety. The survey was available in both English and French. Of the women who started the survey, the completion rate was 70 %. Eleven percent of the participants answered the survey in French. The Concordia University Human Research Ethics Committee approved all procedures.

Participants responded between April 2011 (launch of the survey) and February 2014. Participants were recruited through a variety of means. Forty-seven percent of the participants answered the survey through the Psychology Participant Pool at Concordia University in Montreal and received course credit for their participation. The remaining 53 % consisted of a diversity of women recruited through the community. These women were entered into a draw to win $250. The survey was advertised on Craigslist and Kijiji, which are both websites that post classified advertisements locally. The study was regularly advertised on these two websites in both English and French in Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, and Vancouver. An advertisement for the study was also posted once in two free weekly newspapers in Montreal. Between April 2011 and until the end of 2012, fliers advertising the survey were also regularly posted around all of the four university campuses in Montreal and around the city of Montreal, generally. On two occasions, the study was advertised to Montreal university students not part of the Participant Pool at Concordia University by classroom announcement in courses on gender and sexuality. The study was also posted once to the listserv of the Sexual and Gender Identity Section of the Canadian Psychological Association. Finally, the study was advertised by contacting LGBTQ student groups at universities across Canada.

In order to avoid biasing recruitment toward any one sexual orientation group to the greatest extent possible, the majority of the advertisement for the study called for “women to participate in a questionnaire-based study addressing sexual orientation and identity, sexual and emotional experiences, sexual desire and arousal, and mental health.” Halfway through data collection, the advertisements posted on Craigslist and Kijiji were changed to “looking for women who self-identify as non-heterosexual” in order to boost the number of sexual minority women. Interested women were directed to send an email to express their interest, at which point they were given a participant code and a link to the survey.

Measures

The Sexual Arousal and Desire Inventory (Toledano & Pfaus, 2006)

The Sexual Arousal and Desire Inventory (SADI) is a 54-item descriptive self-report scale intended to measure subjective sexual arousal and desire. Descriptors are rated on a five-point Likert scale, from 0 = “does not describe it at all” to 5 = “describes it perfectly.” The overall scale is composed of four sexual arousal and desire dimensions, namely an “Evaluative” (or cognitive- emotional) component (27 items), a “Physiological” (autonomic and endocrine) component (17 items), a “Motivational” component (10 items), and a “Negative/Aversive” (or inhibitory) component (17 items). Examples of descriptors for the Evaluative component are “happy” and “attractive”; for the Physiological, “hot” and “throbs in genital area”; for the Motivational, “driven” and “anticipatory”, and for the Negative, “anxious” and “unattractive.” The SADI defines sexual arousal “as the physiological responses that accompany or follow sexual desire,” whereas sexual desire is defined as “an energizing force that motivates a person to seek out or initiate sexual contact and behavior.”

Participants were instructed to “indicate to what extent each word describes how you have normally felt while having sex, with a man or with a woman by placing the number that describes the feeling most accurately.” The items for males and females were the same and participants rated their responses for male versus female in alternating order. Cronbach alphas for the Evaluative dimensions (male and female), the Physiological Dimension (male and female), the Motivational Dimension (male and female), and the Negative Dimension (male and female) were .93, .92, .88, .85, .80, .80, .87, and .82, respectively.

Data for the SADI were analyzed for people who reported ever having had sexual contact with a man, with a woman, or with both a man and a woman (as a sexually mature adult). Sexual contact was defined as any sexually motivated intimate contact (any oral sex, vaginal sex, and/or anal sex that was consensual).

In addition to the SADI, results were analyzed for the following variables: current sexual partner (none, male, female, several), historical number of sexual partners (male, female, and total), the average number of times having sex with men and with women per week (coded as 0, 1 [1–4], 2 [5–8], and 3 [9 or more]), the average number of times desiring to have sex per week (coded as 0, 1 [1–4], 2 [5–8], and 3 [9 or more]), and frequency of masturbation (on a scale from 1 = “sometimes” to 5 = “daily”). Frequency of masturbation was only analyzed for those reporting masturbation (n = 354).

Results

Demographics

There were no significant age differences between the sexual orientation groups or in English language fluency. The bisexual group reported less fluency in French than the heterosexual group (M bisexual = 3.10; M heterosexual = 3.70), t(250) = 3.02, p = .003. The groups did not differ in cultural affiliation or in nationality. However, the lesbians reported living longer in an urban setting than did the mostly lesbians (M lesbian = 22.04 years; M mostly lesbian = 16.02 years), t(81) = 2.50, p = .015. The heterosexuals reported being more religious than the other groups, χ 2(4) = 14.58, p = .006.

The groups differed in socioeconomic background (SES), Welch’s F(4, 116.70) = 3.70, p = .007. The mostly lesbian group reported lower SES than the mostly heterosexual group (M mostly lesbian = 1.75; M mostly heterosexual = 2.04), t(83) = 2.90, p = .004. Further, the bisexuals were less educated than the heterosexual and mostly heterosexual groups (M bisexual = 5.30; M heterosexual = 5.90), t(250) = 4.14, p = .001; (M bisexual = 5.30; M mostly heterosexual = 5.94), t(115) = 3.11, p = .002.

Measured Sexual Variables

Of the total sample, 9 (2.3 %) reported never having had sexual contact, 158 (40.7 %) reported ever having had sexual contact with a male only, 27 (7 %) reported ever having had sexual contact with a female only, and 194 (50 %) reported ever having had sexual contact with both a male and a female. Figure 1 illustrates how sexual contact with male and female varied as a function of sexual orientation, while Fig. 2 illustrates current sexual partner based on sexual orientation.

There were no significant differences between the sexual orientation groups in total number of sexual partners (approached significance for bisexual versus heterosexual, p = .071). Lesbians reported significantly more female sexual partners than the heterosexuals and mostly heterosexuals, ps = .001. Further, the lesbians reported significantly fewer male sexual partners than the bisexuals and mostly heterosexuals, p = .014 and p = .028, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates number of sexual partners based on sexual orientation.

The lesbians and mostly lesbians reported having sex more often with women per week than all the other sexual orientation groups (all ps = .001 for lesbian to heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, and bisexual; p = .001 for mostly lesbian to heterosexual and mostly heterosexual; p = .033 for mostly lesbian to bisexual). The bisexuals reported having sex with women more often than the mostly heterosexuals (p = .023). Further, the lesbians and mostly lesbians reported having sex less often with men per week than all the other sexual orientation groups (all ps = .001). The other groups did not differ from each other.

Of the total sample, 34 (8.8 %) women reported not masturbating. In terms of frequency of masturbation, there were no significant differences between the sexual orientation groups. However, there was a trend toward bisexuals and mostly heterosexuals reporting more frequent masturbation than heterosexuals (p = .082 and p = .086, respectively). Further, there were also no significant differences between the groups for self-reported weekly desire for sex. Table 1 reports the means and standard deviations, split by sexual orientation group, for sex per week (with men and with women), frequency of masturbation, and weekly desire for sex.

Between-Group Differences for the SADI

In order to investigate between-group differences in self-reported sexual arousal and desire for sexual contact with men and with women for the five sexual orientation groups, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used. Two separate MANOVAs were run for the four male and the four female dimensions of the SADI. Sexual orientation was entered as the independent variable, and the SADI evaluative, negative, physiological, and motivational dimensions were entered as dependent variables.

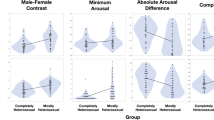

Overall, sexual orientation was significantly associated with the four male dimensions of the SADI, F(4, 335) = 7.61, p < .001, Wilks’ λ = .71, η 2 = .08. The univariate tests indicated that sexual orientation was significantly related to all four male dimensions of the SADI (see Table 2). Table 2 also reports Games–Howell post hoc test results.

As a whole, it was found that sexual orientation was significantly associated with the four female dimensions of the SADI, F(4, 203) = 4.09, p < .001, Wilks’ λ = .73, η 2 = .08. Univariate analyses revealed that sexual orientation was significantly related to all female dimensions of the SADI, except for the negative one (see Table 3). Table 3 also reports Games–Howell post hoc test results.

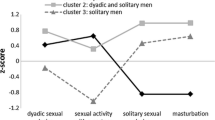

Within-Group Differences for the SADI

In order to test within-group differences in self-reported sexual arousal and desire for sexual contact with men and with women, paired-samples t tests were run for the five sexual orientation groups separately. Overall, it was found that there were no significant differences in self-reported sexual arousal and desire with men versus women for any of the sexual orientation groups, except for on the motivational dimension. Heterosexual and mostly heterosexual women had higher scores on the male motivational dimension than on the female motivational dimension, p = .001 and p = .005, respectively, while the reverse was found for lesbian and mostly lesbian women, p = .001 and p = .025, respectively. For the bisexual group, there were no differences. See Table 4 for the paired-samples t test descriptive statistics.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that a substantial percentage of women defines themselves as mostly heterosexual, bisexual, or as mostly lesbian, and that these women’s subjective sexual arousal and desire in partnered sexual activities differ from those of heterosexual and lesbian women, further validating mostly heterosexual and mostly lesbian as distinct sexual orientations (Savin-Williams & Vrangalova, 2012, 2013). For sexual contact with women, bisexual women reported the highest sexual arousal and desire of all the sexual orientation groups and at levels significantly higher than both lesbian and heterosexual women. However, the three non-monosexual groups did not differ from each other, which suggests that these women’s subjective sexual experiences with women may be more similar to each other than to those of heterosexual and to lesbian women.

Heterosexual women did not report lower sexual arousal and desire toward women than lesbian women did, except for on the motivational dimension. Although our findings are not directly comparable to those from physiological studies due to methodological differences, results suggest that for heterosexual women, sexual arousal and desire may be a poor predictor of self-reported sexual orientation (Bailey, 2009). The results for sexual contact with men were more mixed. Although bisexual women reported the highest levels of sexual arousal and desire, the results were not significant. Lesbian women scored lower than the other groups, underlining their consistently lower arousal and desire toward men compared to other women, who do not tend to differ from each other. These findings raise important questions about the meaning of female sexual orientation. If heterosexual women are not less aroused by sex with women than lesbians are, then why do they not define themselves as lesbians? Diamond (2003b) has argued that romantic love and sexual desire may be independent. One hypothesis is that women of different sexual orientations may place unequal importance on sexual attraction versus romantic attraction. Romantic attraction may be more salient for heterosexual women because, relative to lesbian women, they may be less able to rely on physiological arousal as a sexual orientation guide (Bailey, 2009). Future research should further explore how sexual attraction and romantic attraction correlate for heterosexual women in comparison to lesbian women.

It has been speculated that men’s sexual arousal patterns may be related to sexual inhibition (Bailey, Rieger, & Rosenthal, 2011; Rosenthal, Sylva, Safron, & Bailey, 2012). In short, in contrast to gay men, bisexual men may not be averse to sexual stimuli featuring women. Findings from the current study do not support the sexual inhibition hypothesis for women. In order for this theory to be confirmed, one would expect (1) lesbians to rate men higher on the negative dimension of the SADI, and (2) heterosexuals to rate women higher on the negative dimension of the SADI. In the current study, the only observed difference on the negative dimension of the SADI was between bisexuals and heterosexuals for sexual contact with men, suggesting that bisexual women may feel more aversion during sex with men than heterosexual women do. Rather that arguing that bisexuals may be bisexual due to a lack of sexual inhibition, this finding instead raises the possibility that bisexual women define themselves as such because they are more averse to sex with men than heterosexuals are. In sum, male and female bisexuality may be driven by different mechanisms. It is noteworthy that in the current study, bisexual women reported higher sexual arousal and desire but also more aversion. Future studies should further explore which mechanisms may be related to both high positive and high negative sexual arousal.

Our findings suggest that sexual arousal and desire toward men versus women may not necessarily be inversely related, especially for bisexual women. If arousal and desire toward men and women were inversely related, then bisexual women would be expected to report, for example, lower arousal and desire toward women than lesbian women do. However, in our study, bisexual women reported higher levels of sexual arousal and desire toward women than the lesbian women did. Illustratively, Vrangalova and Savin-Williams (2012) found that mostly heterosexual and mostly lesbian women were equally high in opposite and same-sex sexuality as heterosexual and lesbian women, implying that being less exclusive does not mean less attraction to men or to women, as would be expected if sexual orientation is one dimensional. In short, our findings echo those of Vrangalova and Savin-Williams (2012), lending further support to the theory that sexual orientation may not be one dimensional.

Overall, results of this research indicate that women who have had sexual contact with men and with women, regardless of their sexual orientation, do not rate their sexual arousal and desire with men versus women differently, except for in their motivation to engage in sexual activity. One theory that follows from these findings is that women define their sexual orientation in terms of their motivation to engage in sexual activity with men versus women and not in terms of how they feel when they are actually engaging in sexual activity. In short, bisexual women may be bisexual because they feel equally sexually motivated with men and with women while that may not be the case for the other sexual orientation groups. The motivational factor of the SADI is similar to the concept of female proceptivity, which is considered a woman’s motivation to initiate sexual contact (Beach, 1976; Diamond, 2007; Diamond & Wallen, 2011). In her book on female sexual fluidity, Diamond (2008b) contended female sexual orientation is only “coded” into proceptivity and not into arousability, which she defines as “a person’s capacity to become aroused once certain triggers, cues, or situations are encountered” (p. 202). The findings of the current study support Diamond’s (2008b) assertion: women rated men and women the same, except for on the motivational dimension. Further, Chivers (2010) has argued that female non-concordance and non-specificity are examples of “a relative independence between physiological, psychological, and behavioral aspects of sexual arousal in women” (p. 416). The fact that the women included in this study did not differentiate men and women on the physiological dimension of the SADI, regardless of their stated sexual orientation, further underlines the fact that sexual orientation for women is not equal to their autonomic responses per se. Chivers et al. (2007) found that although lesbian women displayed category-specific vaginal responding to depictions of exercise or masturbation, they did not to images of intercourse. These findings suggest that once a sexual situation is sufficiently intense, women, regardless of stated sexual orientation, may be more driven by physiology than by motivation. In their meta-analysis, Chivers et al. (2010) argue that women’s genital arousal may be automatically triggered to both preferred and non-preferred sexual stimuli, which again suggests that for women, sexual arousal may not necessarily be linked to conscious motivation for sexual contact.

The fact that the bisexual women in the current study reported higher sexual arousal and desire scores than the heterosexual and the lesbian women (although not significantly so for males) is in line with Lippa’s (2007) findings, which documented higher sex drive among bisexual than heterosexual and lesbian women. Lippa (2007) argued bisexual women’s high sex drive may “energize” latent same-sex attractions (or other-sex attractions), and it is possible that the same mechanism may be at work for mostly heterosexual and mostly lesbian women. In short, the finding that the lesbian women in this research did not report higher sexual arousal and desire toward women than the heterosexual women did could be a reflection of a generalized lower sex drive among monosexual than non-monosexual women.

Other research has found that bisexuality may be associated with elevated levels of sexual curiosity and sociosexuality (Rieger et al., 2013; Schmitt, 2005). For instance, cross-culturally, bisexual women score higher on sociosexuality than heterosexual and lesbian women do (Schmitt, 2005). Bisexual women’s higher sex drive and greater sociosexuality could help explain why they scored significantly higher than lesbians and heterosexuals on the female dimensions of the SADI but not on the male dimensions. Lippa (2007) made the assumption that bisexual women are mostly heterosexual women with a high sex drive; considering that heterosexuality is considered normative, high sex drive may only be evident in non-normative sexuality, in effect, lesbianism. Basically, bisexual women’s high sex drive may not be obvious in heterosexual activities because they do not have to “energize” what is non-normative.

Even if the bisexual women in the current study reported higher levels of sexual arousal and desire than the heterosexual and lesbian women did, they did not proclaim a greater number of total sexual partners, more frequent masturbation, or elevated levels of weekly sexual desire. In short, the current research does not support the stereotype that bisexual women are sexually promiscuous (Israel & Mohr, 2004; Rust, 1995, 2000). In sum, bisexual women may have the “best of both worlds,” in that they report high levels of arousal and desire, without this translating into promiscuity.

Strengths and Limitations

One of the main strengths of this research is that women were broadly recruited and that there was not a call for participants based on any one specific sexual orientation. Past research on sexual minorities may have been limited due to mainly recruiting participants from LGBT community organizations and LGBT student groups, and we attempted to avoid this limitation by recruiting from diverse settings. Further, participants varied in nationality, language, and demographics, implying results may be generalized to women from divergent backgrounds. However, despite attempting to get a heterogeneous sample, participants were still only recruited in Canada and mainly in Montreal, Quebec. In addition, our findings may be limited by a cohort effect. The majority of women were below the age of 30, for whom bisexual experiences may be considered more common than for older women. For example, one of the main findings from the third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL) is that lifetime female same-sex experiences have quadrupled from 1990 (for women aged 16–44), namely from 4 % then (Johnson, Wadsworth, Wellings, & Field, 1994) to 16 % currently (Mercer et al., 2013).

Further, we only measured subjective sexual arousal and desire. In short, our focus was not on the interrelation of physiological and subjective arousal but rather on the type of subjective experience that contributes in a conscious way to erotic response. However, as noted previously, subjective and genital sexual arousal in women may not show concordance (for a meta-analysis, see Chivers et al., 2010). Although the self-reported sexual arousal and desire of mostly heterosexual, bisexual, and mostly lesbian women were similar to each other in this study, it is possible that their genital arousal may be more similar to lesbian or to heterosexual women. In addition, women’s subjective ratings here were based on their memory of sexual contact with men, with women, or with both men and women. Therefore, memory bias cannot be ruled out.

Due to previous lack of research on the sexual arousal and desire of non-monosexual women in comparison to monosexual women, the main goal of this research was to test whether sexual orientation differences exist. However, although this study was not intended to specify mediators, we note that interpretation of sexual orientation differences may be limited due to not accounting for several potential sources of variability. For example, we did not control for women’s current sexual partner status or length of time since their last sexual contact. As Diamond (2008a, b) has demonstrated, female sexual attractions may fluctuate over time and by relationship status. Therefore, it is possible that results could have been different if we had taken into account the gender of the women’s current sexual partner. Future studies may want to investigate how several aspects of sexual history, such as satisfaction in sexual relationships with men and women, number of sexual partners, and sexual victimization may be related to sexual arousal and desire. For instance, research has found that women who identity as bisexual may report more lifetime sexual partners and higher rates of sexual victimization than monosexual women (Hequembourg, Livingston, & Parks, 2013; Lehavot, Molina, & Simoni, 2012).

Further, women’s sexual arousal may be related to the intensity of sexual stimuli (Chivers et al., 2007). As Chivers et al. have demonstrated, lesbian women’s genital arousal is category-specific to stimuli depicting nudity and masturbation but non-specific to stimuli depicting intercourse. In the current study, sexual contact was defined as including both oral sex and intercourse. It is possible that results may have varied if, for example, participants had been asked to rate their arousal and desire for different types of sexual activities.

Women’s sexual arousal and desire may also be associated with their menstrual cycle (Diamond & Wallen, 2011; Suschinsky, Bossio, & Chivers, 2014). Although our findings suggest that bisexual women may not differentiate their subjective sexual arousal and desire with men versus women overall, future studies should continue to explore how these women’s self-reports may vary by hormonal levels. For example, it is possible that around the time of ovulation, memories of sexual contact with men may be more salient than memories of sexual contact with women, which could translate into higher sexual arousal ratings for men than for women during this time.

Also, our research speaks to subjective trait and not subjective state, differences in sexual arousal and desire. Future laboratory sexual arousal and desire studies should include bisexual, mostly heterosexual, and mostly lesbian women in order to assess whether they differ from monosexual women in response to sexual stimuli. Our findings of subjective trait sexual arousal and desire indicate that future studies measuring genital and subjective sexual arousal may benefit from analyzing mostly heterosexual, bisexual, and mostly lesbian women separately from the exclusive categories. However, if collapsing categories are necessary to increase group sizes, our findings suggest that it may be more valid combining the three non-monosexual groups rather than placing them into a heterosexual or a lesbian category.

Finally, there has been a call for research to include sexual identity as a covariate when analyzing sexual arousal and desire in response to sexual stimuli (Goldey & van Anders, 2012). The current study underlines the importance of separating women based on a five-category sexual orientation approach, and we contend that future studies on sexual arousal and desire should follow this methodology rather than excluding non-monosexual women.

References

Bailey, J. M. (2009). What is sexual orientation and do women have one? In D. A. Hope (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities (Vol. 54, pp. 43–63). New York, NY: Springer.

Bailey, J. M., Rieger, G., & Rosenthal, A. (2011). Still in search of bisexual sexual arousal: Comment on Cerny and Janssen (2011). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(6), 1293–1295. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9778-5.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 347–374.

Beach, F. A. (1976). Sexual attractivity, proceptivity, and receptivity in female mammals. Hormones and Behavior, 7(1), 105–138. doi:10.1016/0018-506X(76)90008-8.

Bossio, J. A., Suschinsky, K. D., Puts, D. A., & Chivers, M. L. (2014). Does menstrual cycle phase influence the gender specificity of heterosexual women’s genital and subjective sexual arousal? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 941–952. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0233-7.

Chivers, M. L. (2010). A brief update on the specificity of sexual arousal. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 25(4), 407–414. doi:10.1080/14681994.2010.495979.

Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2005). A sex difference in features that elicit genital response. Biological Psychology, 70(2), 115–120. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.12.002.

Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2007). The sexual psychophysiology of sexual orientation. In E. Janssen (Ed.), The psychophysiology of sex (pp. 458–474). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Chivers, M. L., Rieger, G., Latty, E., & Bailey, J. M. (2004). A sex difference in the specificity of sexual arousal. Psychological Science, 15(11), 736–744. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00750.x.

Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., & Blanchard, R. (2007). Gender and sexual orientation differences in sexual response to sexual activities versus gender of actors in sexual films. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1108–1121. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1108.

Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., Lalumière, M., Laan, E., & Grimbos, T. (2010). Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(1), 5–56. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9556-9.

Chivers, M. L., & Timmers, A. D. (2012). Effects of gender and relationship context in audio narratives on genital and subjective sexual response in heterosexual women and men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 185–197. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9937-3.

Diamond, L. M. (1998). Development of sexual orientation among adolescent and young adult women. Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 1085–1095. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.1085.

Diamond, L. M. (2000). Sexual identity, attractions, and behavior among young sexual minority women over a 2-year period. Developmental Psychology, 36(2), 241–250. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.241.

Diamond, L. M. (2003a). Was it a phase? Young women’s relinquishment of lesbian/bisexual identities over a 5-year period. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 352–364. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.352.

Diamond, L. M. (2003b). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110(1), 173–192. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.110.1.173.

Diamond, L. M. (2005). A new view of lesbian subtypes: Stable versus fluid identity trajectories over an 8-year period. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29(2), 119–128. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00174.x.

Diamond, L. M. (2007). The evolution of plasticity in female-female desire. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 18, 245–274. doi:10.1300/J056v18n04_01.

Diamond, L. M. (2008a). Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 5–14. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5.

Diamond, L. M. (2008b). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Diamond, L. M., & Wallen, K. (2011). Sexual minority women’s sexual motivation around the time of ovulation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 237–246. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9631-2.

Ebsworth, M., & Lalumière, M. L. (2012). Viewing time as a measure of bisexual sexual interest. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 161–172. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9923-9.

Goldey, K. L., & van Anders, S. M. (2012). Sexual arousal and desire: Interrelations and responses to three modalities of sexual stimuli. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(9), 2315–2329. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02845.x.

Hequembourg, A. L., Livingston, J. A., & Parks, K. A. (2013). Sexual victimization and associated risks among lesbian and bisexual women. Violence Against Women, 19(5), 634–657. doi:10.1177/1077801213490557.

Israel, E., & Strassberg, D. (2009). Viewing time as an objective measure of sexual interest in heterosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(4), 551–558. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9246-4.

Israel, T., & Mohr, J. J. (2004). Attitudes toward bisexual women and men: Current research, future directions. In R. C. Fox (Ed.), Current research on bisexuality (pp. 117–134). Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press/The Haworth Press.

Johnson, A. M., Wadsworth, J., Wellings, K., & Field, J. (1994). The National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Press.

Laan, E., Sonderman, M., & Janssen, E. (1995). Straight and lesbian women’s sexual responses to straight and lesbian erotica: No sexual orientation effects. Poster presented at the meeting of the International Academy of Sex Research, Provincetown, MA.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lehavot, K., Molina, Y., & Simoni, J. (2012). Childhood trauma, adult sexual assault, and adult gender expression among lesbian and bisexual women. Sex Roles, 67(5–6), 272–284. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0171-1.

Lhomond, B., Saurel-Cubizolles, M.-J. P., Michaels, S., & The CSF Group. (2014). A multidimensional measure of sexual orientation, use of psychoactive substances, and depression: Results of a national survey on sexual behavior in France. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 607–619. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0124-y.

Lippa, R. A. (2006). Is high sex drive associated with increased sexual attraction to both sexes? It depends on whether you are male or female. Psychological Science, 17(1), 46–52. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01663.x.

Lippa, R. A. (2007). The relation between sex drive and sexual attraction to men and women: A cross-national study of heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(2), 209–222. doi:10.1007/s10508-006-9146-z.

Lippa, R. A. (2013). Men and women with bisexual identities show bisexual patterns of sexual attraction to male and female ‘swimsuit models’. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(2), 187–196. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9981-z.

Mercer, C. H., Tanton, C., Prah, P., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., … Johnson, A. M. (2013). Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: Findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet, 382(9907), 1781–1794. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8.

Mustanski, B. S., Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2002). A critical review of recent biological research on human sexual orientation. Annual Review of Sex Research, 13, 89–140.

Rieger, G., Rosenthal, A. M., Cash, B. M., Linsenmeier, J. A. W., Bailey, J. M., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2013). Male bisexual arousal: A matter of curiosity? Biological Psychology, 94(3), 479–489. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.09.007.

Rosenthal, A. M., Sylva, D., Safron, A., & Bailey, J. M. (2012). The male bisexuality debate revisited: Some bisexual men have bisexual arousal patterns. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 135–147. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9881-7.

Rullo, J., Strassberg, D., & Israel, E. (2010). Category-specificity in sexual interest in gay men and lesbians. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 874–879. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9497-3.

Rust, P. C. (1992). The politics of sexual identity: Sexual attraction and behavior among lesbian and bisexual women. Social Problems, 39(4), 366–386.

Rust, P. C. (1995). Bisexuality and the challenge to lesbian politics: Sex, loyalty, and revolution. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Rust, P. C. (2000). Bisexuality: A comtemporary paradox for women. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 205–221. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00161.

Savin-Williams, R. C. (2006). Who’s gay? Does it matter? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(1), 40–44. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00403.x.

Savin-Williams, R. C. (2009). How many gays are there? It depends. In D. A. Hope (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities (vol. 54, pp. 5–41): New York, NY: Springer.

Savin-Williams, R. C., & Vrangalova, Z. (2013). Mostly heterosexual as a distinct sexual orientation group: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Developmental Review, 33(1), 58–88. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2013.01.001.

Schmitt, D. P. (2005). Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: A 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28(2), 247–311. doi:10.1017/S0140525X05000051.

Shively, M. G., & De Cecco, J. P. (1977). Components of sexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 3(1), 41–48. doi:10.1300/J082v03n01_04.

Storms, M. D. (1980). Theories of sexual orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 783–792. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.38.5.783.

Suschinsky, K. D., Bossio, J. A., & Chivers, M. L. (2014). Women’s genital sexual arousal to oral versus penetrative heterosexual sex varies with menstrual cycle phase at first exposure. Hormones and Behavior, 65(3), 319–327. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.01.006.

Suschinsky, K. D., & Lalumière, M. (2012). Is sexual concordance related to awareness of physiological states? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 199–208. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9931-9.

Suschinsky, K. D., Lalumière, M. L., & Chivers, M. L. (2009). Sex differences in patterns of genital sexual arousal: Measurement artifacts or true phenomena? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(4), 559–573. doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9339-8.

Toledano, R., & Pfaus, J. (2006). The Sexual Arousal and Desire Inventory (SADI): A multidimensional scale to assess subjective sexual arousal and desire. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 3(5), 853–877. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00293.x.

van Anders, S. (2012). From one bioscientist to another: Guidelines for researching and writing about bisexuality for the lab and biosciences. Journal of Bisexuality, 12(3), 393–403. doi:10.1080/15299716.2012.702621.

Vrangalova, Z., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2012). Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 85–101. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9921-y.

Acknowledgments

TJP was supported by a doctoral scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Persson, T.J., Ryder, A.G. & Pfaus, J.G. Comparing Subjective Ratings of Sexual Arousal and Desire in Partnered Sexual Activities from Women of Different Sexual Orientations. Arch Sex Behav 45, 1391–1402 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0468-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0468-y