Abstract

This study compared male and female university students’ experiences with online sexual activity (OSA) and tested a model explaining gender differences in OSA. OSAs were categorized as non-arousal (e.g., seeking sexuality information), solitary-arousal (e.g., viewing sexually explicit materials), or partnered-arousal (e.g., sharing sexual fantasies). Participants (N = 217) completed measures of OSA experience, sexual attitudes, and sexual experience. Significantly more men than women reported engaging in solitary-arousal and partnered-arousal OSA and doing so more often. However, the men and women who reported having engaged in partnered-arousal activities reported equal frequencies of experience. There were no significant gender differences for engaging in non-arousal OSA experience. These results support the importance of grouping OSAs in terms of the proposed non-arousal, solitary-arousal, and partnered-arousal categories. Attitude toward OSA but not general attitudes toward or experiences with sexuality partially mediated the relationship between gender and frequency of engaging in arousal-oriented OSA (solitary and partnered OSA). This suggests that attitude toward OSA specifically and not gender socialization more generally account for gender differences in OSA experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Internet provides a dynamic and ever-evolving medium for sexual expression and information. Online sexual activity (OSA) refers to the use of the Internet for activities of a sexual nature (Cooper & Griffin-Shelley, 2002). To date, researchers have focused on describing OSA experiences. In doing so, some researchers have differentiated activities in terms of the goals of information seeking, relationships, and sexual gratification (e.g., Boies, 2002; Goodson, McCormick, & Evans, 2001). Other researchers have grouped together any use of sexually explicit material on the Internet (e.g., Byers, Menzies, & O’Grady, 2004; Traeen, Nilsen, & Stigum, 2006). In contrast, offline sexual activities are typically differentiated in terms of whether they are arousal-oriented and whether they are solitary or involve a partner (Rye & Meaney, 2007; Spector, Carey, & Steinberg, 1996). These distinctions have resulted in a nuanced understanding of the differential effects of gender role socialization on various offline sexual behaviors. It is likely that gender roles affect some but not all types of online sexual behavior. Therefore, we examined gender differences in three categories of OSA: non-arousal activities (e.g., seeking sexual information); solitary-arousal activities (e.g., viewing sexually explicit videos); and, partnered-arousal activities (e.g., maintaining a sex partner online). These categories lend themselves towards a theoretical examination of gender differences. We also examined the extent to which sexual attitudes and offline sexual experience mediate the relationship between gender and OSA experience.

Gender and OSA Experience

Socialization results in different sexual scripts for men and women (Gagnon & Simon, 1973; Wiederman, 2005). For example, the traditional sexual script (TSS; Byers, 1996), prevalent in North America, posits that men have strong sexual needs and motivations that, when acted upon, enhance their social status. In contrast, women are expected to have few sexual needs, attach sexual activity to emotion and commitment, and experience status decreases with increasing sexual experience. As such, the TSS creates permissiveness for arousal-oriented sexual behaviors in men but not in women. Researchers who rely on evolutionary theories expect these same gender differences due to historical strategies for reproductive success (Schwartz & Rutter, 2000). In keeping with these predictions, literature reviews have revealed consistent findings that, compared to women, men engage in intercourse at a higher frequency and younger age, masturbate more frequently, watch pornography more frequently, and have more casual sexual partners (Baumeister, Catanese, & Vols, 2001; Peterson & Hyde, 2010). In addition, compared to men, women expect sexual activity to begin later in a relationship, suggesting that women see sexual activity in the context of an ongoing relationship (Baumeister et al., 2001). These findings support separation of sexual pleasure and relationships for men but not for women. It is likely that differential socialization affects the extent to which men and women engage in some but not all types of OSA.

Non-arousal OSAs do not require men and women to express themselves sexually. Thus, based on the TSS, men and women would not be expected to differ in their experiences with these activities. However, findings about gender differences in non-arousal OSA have been mixed depending on the population studied. In student samples, researchers have found that more men than women report using Internet dating sites and seeking sexual information online and that they do so more frequently (Boies, 2002; Goodson et al., 2001). In contrast, in a sample of non-student Internet users, Cooper, Morahan-Martin, Mathy, and Maheu (2002) found no significant difference between men and women in seeking online dating partners and that more women than men have sought sexual information online. Unfortunately, researchers have relied on categorical rather than continuous measures of frequency of OSA experience and these can obscure relative gender differences. Therefore, we examined both the percentage of men and women who reported experience with non-arousal OSAs as well as how often they had participated in these activities. We expected that an equal number of men and women would have engaged in non-arousal OSA and would have done so at similar frequencies.

In contrast, solitary-arousal OSAs reflect the separation of sexual pleasure from relationships. Therefore, according to the TSS, more men than women would be expected to participate in solitary-arousal OSAs and at a greater frequency. Indeed, researchers have found that, compared to undergraduate women, more undergraduate men reported accessing and viewing sexually explicit material online and masturbating while online, as well as doing so more frequently (Boies, 2002; Byers et al., 2004; Goodson et al., 2001). However, in calculating the frequency of solitary-arousal OSA experience, these researchers included individuals who had and had not engaged in the behavior. Because more men than women engage in solitary-arousal OSA, it may be that men’s greater frequency of experience is an artefact of the fact that more women have no experience. Therefore, we predicted that more men than women would report experience with solitary-arousal OSA and that men would report a greater frequency of experience in the full sample as well as within the subsample of men and women who have engaged in these activities.

Finally, it is not clear how partnered-arousal OSAs fit with prescriptions based on the TSS. On the one hand, these activities involve sexual pleasure. Therefore, it would be expected that they fit into the prescribed realm of sexual expression for men but not for women. This suggests that more men than women would report partnered-arousal OSA experience and would report doing so more frequently. On the other hand, the partnered aspect implies a relationship context, particularly when the activity involves interacting with the same person on more than one occasion (e.g., maintaining a sexual relationship online). Sexual activity within a relational context is consistent with the TSS prescription for both men and women. Thus, it may be that as many women as men engage in partnered-arousal activities and at a similar rate. Finally, it may be that the TSS has different implications for whether women initially participate in partnered-arousal OSA than for the frequency with which they engage in it once involved. That is, prior to participating in partnered-arousal OSA, the characteristic of sexual pleasure may be more salient than the characteristic of the relationship context. As such, more men than women would report having had partnered-arousal OSA experience. However, for individuals who do participate in this type of OSA, the relational aspect may become a primary component of the activity. As such, men and women who participate in partnered-arousal OSA would report similar frequencies of experience. Given these alternatives and the lack of previous research on partnered-arousal OSA, we did not offer a prediction regarding gender differences.

The Roles of Sexual Attitudes and Offline Experience in Explaining OSA Experience

Researchers have not investigated mechanisms that may account for gender differences in OSA experience. Based on the TSS, we proposed that socialization leads men to have more liberal, permissive, and positive sexual attitudes as well as more offline sexual experience than women and these, in turn, lead to more frequent arousal-oriented (solitary-arousal and partnered-arousal) OSA experience. That is, we proposed that sexual attitudes and sexual experience mediate the relationship between gender and frequency of arousal-oriented OSA experience. There is support for some of these relationships.

First, research has shown that, compared to women, men subscribe to more permissive and liberal sexual attitudes (Baumeister et al., 2001; Peterson & Hyde, 2010). Additionally, individuals with more permissive and liberal sexual attitudes tend to report more offline partnered and autoerotic sexual experience (Ku et al., 1998; Lopez & George, 1995; Simpson & Gangestad, 1991; Yost & Zurbriggen, 2006). Although it is likely that sexual attitudes are also associated with OSA experience, to our knowledge no one has examined this association. We selected two measures of sexual attitudes that we expected would affect OSA because they reflect openness toward sexual expression: sociosexual orientation and liberal-conservative sexual attitudes. Sociosexual orientation refers to degree of comfort or acceptance of casual sexual activity (Simpson & Gangestad, 1991). Liberal-conservative sexual attitudes refer to the beliefs that sexual expression should be open, free, and unrestricted (Hudson, Murphy, & Nurius, 1983). We expected that individuals who were more open to a range of sexual expression would also be more open to engaging in arousal-oriented OSA.

Researchers have documented the importance of attitude specificity in predicting target behaviors (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977; Albarracin, Johnson, Fishbein, & Muellerleile, 2001; Cha, Doswell, Kim, Charron-Prochonwnik, & Patrick, 2007). Thus, it may be that specific attitudes regarding OSA are more important to understanding men and women’s different arousal-oriented OSA experience than are general sexual attitudes. Therefore, we also assessed attitudes toward OSA specifically. Compared to women, men have been found to report more positive attitudes toward sexually explicit material offline, and more positive expectations, expectancies, and reactions to sexually explicit material online (Boies, 2002; Goodson et al., 2001; O’Reilly, Knox, & Zusman, 2007). However, researchers have not examined attitudes toward OSA more generally. Nonetheless, we predicted that men would have more positive attitudes toward OSA than would women and that individuals with more positive attitudes toward OSA would report more frequent arousal-oriented OSA experience.

In addition, men consistently report more offline sexual partners than do women (Peterson & Hyde, 2010). Although there is evidence that for heterosexual men and women this difference is an artefact of self-reports biased by gender normative expectation (Alexander & Fisher, 2003), we chose to examine reported number of sexual partners as a mediator in the model. Traeen et al. (2006) found that both men and women who reported more offline sex partners also reported more experience with sexually explicit material online. However, Boies (2002) found that the number of offline sexual partners is not associated with frequency of viewing sexually explicit material online. Thus, the extent to which the number of offline sexual partners is associated with engaging in the full range of arousal-oriented OSAs is not known. We predicted that men would report more offline sexual partners than women and that individuals with more offline sexual partners would report more frequent arousal-oriented OSA experience.

Method

Participants

There were 217 participants (108 men and 109 women). Twenty additional participants were dropped: one because gender was not specified, three due to missing data, and 16 to increase the homogeneity of the sample (i.e., only 13 were not heterosexual and only three were over 40 years old with the rest under 30). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 28 years old (M = 19.5, SD = 2.0), with the majority (46.5%) being 18 years old. Most participants were in a relationship with one person (58.8%); 38.4% indicated they were not seeing anyone romantically. The mean number of reported lifetime sexual partners was 2.7 (SD = 2.9) and ranged from 0 to 16.

Measures

Background Questionnaire

A background questionnaire was used to assess participants’ demographic characteristics, relationship status, and number of sexual partners (“How many sexual partners have you had?”).

Online Sexual Experience Questionnaire

Nine items were developed to examine participants’ non-arousal (2 items), solitary-arousal (4 items), and partnered-arousal (3 items) OSA experience. Items are listed in the Appendix. Participants rated the frequency with which they had engaged in each behavior during the past month on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from never (0) to once a day or more (5). The nine items were averaged to create an overall OSA frequency score (Cronbach’s α = .77). In addition, three subscales were created using the mean scores: Non-Arousal OSA, Solitary-Arousal OSA, and Partnered-arousal OSA. Means, rather than total scores, were used in order to take into account the different number of items per subscale.

Attitude Toward Online Sexual Activity

Participants rated their thoughts and feelings in reference to the nine OSAs listed. They responded to the question “What do you think about engaging in behaviors involving computer use such as those listed…” by rating 10, 7-point bipolar scales (e.g., very morally wrong to very morally right; dirty to very pure). Ratings were summed with higher sores representing more positive views toward OSA. Internal consistency for the scale was high, α = .93.

Sexual Attitude Scale (Hudson et al., 1983)

The 25-item Sexual Attitude Scale was used to measure liberal versus conservative attitudes toward sexuality. Participants rated their agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) (e.g., What two consenting adults do together is their business, I think there is too much sexual freedom given to adults these days). Hudson et al.’s procedure for calculating a total score was used, with scores ranging from 0–100 and higher scores indicating more conservative attitudes. Hudson et al. (1983) reported that the scale has high internal consistency (α = .88 in the current study) and demonstrated construct and factorial validity.

Sociosexual Orientation Inventory (Simpson & Gangestad, 1991)

This 7-item scale measures participants’ willingness to engage in uncommitted sexual relations. It contains behavioral (e.g., With how many different partners have you had sex on one and only one occasion?) and attitudinal (e.g., Sex without love is ok) items with varying response scales. Simpson and Gangestad’s published weighted score calculations were used to create a total score ranging from 10 (maximally restricted orientation) to 1,000 (maximally unrestricted orientation) with a normal range in post-secondary samples of 10–250. Thus, higher scores indicate greater acceptance of casual sex. Simpson and Gangestad (1991) have shown the measure to contain a single factor and to be reliable and valid (α = .75 in the current study).

Procedure

Participants were recruited to participate in a study about sexual opinions and experiences through announcements in introductory courses and notices throughout campus at a mid-sized Canadian university. Interested students were invited to complete the questionnaire in small groups (up to 15), in a data collection room that provided individual desk carrels with dividers between participants to ensure confidentiality. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to completing the questionnaire package that stressed confidentiality and freedom to withdraw. The background questionnaire was always presented first in the package. The remaining questionnaires were counterbalanced with additional measures as part of a larger study of students’ sexual definitions and experiences (Byers, Henderson, & Hobson, 2009). After completing the questionnaire package, participants were provided with a debriefing sheet informing them about the study as well as providing contact information for the researchers. Introductory course participants received bonus points; all other participants were entered into a raffle. Data were collected in 2005. The project was approved by the university Research Ethics Board.

Results

OSA Experience

Overall, almost three quarters of the sample reported experience with at least one OSA. More than half reported experience with solitary-arousal OSAs; only one-third reported non-arousal OSA experience; about one quarter reported partnered-arousal OSA experience (see Table 1). Although some participants reported engaging in these behaviors three or four times a week, on average participants reported engaging in non-arousal (M = 0.23), solitary-arousal (M = 0.94), or partnered-arousal (M = 0.14) between never and once a month. Non-arousal OSA was significantly related to frequency of solitary-arousal OSA (r = .18, p < .01), and of partnered-arousal OSA (r = .17, p < .01). More frequent solitary-arousal OSA was significantly related to more frequent partnered-arousal OSA (r = .26, p < .001).

Regarding gender differences, we first examined the percentages of men and women who had experience with each subtype of OSA (see Table 1). Consistent with our prediction, the percentage of the men and the women reporting non-arousal OSA experience did not differ, χ2 = 1.62, p = .20. However, significantly more men than women reported solitary-arousal OSA experience and partnered-arousal OSA experience, χ2 = 49.29, p < .001 and χ2 = 5.08, p = .02, respectively.

Next, we examined gender differences in the frequency of OSA experience. These results are reported in Table 2. The results of a one-way ANOVA using the overall OSA experience score revealed that the men reported significantly more frequent OSA experience than did the women. To examine whether this gender difference occurred for each type of OSA experience, we used a one-way MANOVA with the OSA experience subscales (Non-Arousal OSA, Solitary-Arousal OSA, and Partnered-Arousal OSA) as three dependent variables. The overall test was significant, F(3, 206) = 44.33, p < .001, η2 = 0.39. Follow-up ANOVAs revealed that the men and the women reported similar frequencies of Non-Arousal OSA experience but that the men reported more frequent Solitary-Arousal and Partnered-Arousal OSA experience than did the women. Finally, because many participants reported no OSA experience, using three separate one-way ANOVAs, we also examined whether the gender differences remained when the men and the women who had not reported the respective OSA experience were removed from the analysis. The results indicated that the men and women who had engaged in Non-Arousal OSA did not differ in their reported frequency of doing so. Similarly, the men and women who reported Partnered-Arousal experience did not differ in their reported frequency of these experiences. Consistent with our prediction, among men and women who engaged in Solitary-Arousal OSA, the men reported doing so significantly more frequently than did the women. Nevertheless, the frequency was low for both the men (about two or three times a month) and the women (about once a month).

The Roles of Offline Experience and Sexual Attitudes in Explaining OSA Experience

Means, SDs, and correlations for the variables used to test the mediational model are reported in Table 3. Because the men reported significantly more frequent experience with solitary-arousal and partnered-arousal OSA than the women, we combined these two subscales into a single Arousal-oriented OSA (AR-OSA) subscale for the mediational analyses. An examination of the correlations between the predictor variables and frequency of solitary-arousal and partnered-arousal OSA experience separately revealed the same pattern of results as reported below, supporting our use of the combined dependent variable in the analyses.

We predicted that men would report more liberal sexual attitudes, greater acceptance of casual sex, more positive attitudes toward OSA, and more offline sexual partners than would women. Consistent with our predictions, an examination of the simple correlations between gender and these variables revealed that the men reported significantly greater acceptance of casual sex, more positive attitudes toward OSA, and a greater number of sexual partners than did the women. However, the men and women reported similar sexual attitudes (see Table 3). Additionally, the simple correlations between AR-OSA and both sexual attitudes and number of offline sexual partners were not significant. Therefore, sexual attitudes and number of offline sex partners were not included in further analyses.

We used 5000 bootstrap resamples to test a multiple mediator model estimating the following parameters: (1) direct effect of gender on the mediators (acceptance of casual sex and attitude toward OSA); (2) direct effect of the mediators on the dependent variable (AR-OSA); (3) total (i.e., direct and indirect) effect of gender on the dependent variables; and (4) indirect effect of gender on the dependent variable through each of the mediators. Bootstrapping involves estimating the desired statistic by using the available data and randomly resampling with replacement to generate a distribution of the statistics over multiple resamples. This distribution is then treated as “an empirical estimate of the sampling distribution of that statistics” (Ganesalingam, Sanson, Anderson, & Yeates, 2007, p. 302). As such, it is an approach to hypothesis testing that avoids assumptions about the shape of the distribution of variables or sampling distribution of the statistic (for further discussion, see Preacher & Hayes, 2008). We used Preacher and Hayes SPSS macro for estimating multiple mediator models with bootstrapping to test our modified model. A summary of the bootstrapping analyses is shown in Table 4.

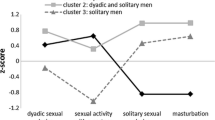

The hypothesized paths between gender, acceptance of casual sex, attitude toward OSA, and AR-OSA and the resulting coefficients are depicted in Fig. 1. As expected, gender significantly predicted acceptance of casual sex and attitudes toward OSA, such that men reported greater acceptance and more positive attitudes than did women. Attitude toward OSA, but not acceptance of casual sex, uniquely predicted AR-OSA experience such that individuals with more positive attitudes toward OSA also reported more AR-OSA experience. Only attitude toward OSA significantly mediated the relationship between gender and AR-OSA experience. The direct effect of gender, independent of attitudes, as well as the total effect (direct and indirect) of gender were significant. These findings suggest that gender contributes to AR-OSA experience directly and also indirectly through its relationship with attitudes toward OSA.

Path diagram depicting the relationships among gender, acceptance of casual sex, attitudes toward OSA, and arousal-oriented OSA experience. Note: N = 209. Unstandardized coefficients for the direct paths are labelled on the arrows whereas the unstandardized coefficients and 95% confidence interval of the indirect effects of gender on arousal-oriented OSA through each attitude mediator are marked inside the attitude variable. Total direct and indirect effect of gender on arousal-oriented OSA experience is −0.62, * p < .001

Discussion

The goal of this study was to extend our understanding of gender differences in OSA experience by differentiating between non-arousal, solitary-arousal, and partnered-arousal OSA. The pattern of gender differences suggests that arousal versus non-arousal and solitary versus partnered were key dimensions for understanding differences in men and women’s OSA experience. We also demonstrated that attitudes toward OSA specifically but not general sexual attitudes or experience account in part for gender differences.

Who Engages in Various OSAs?

The popular media promotes the view that OSA is prevalent, particularly among men (e.g., Field, 2009). Nonetheless, our findings were consistent with past research in suggesting that OSA, even among this young, computer-literate sample, was not as prevalent as might be expected (Boies, 2002; Goodson et al., 2001). A minority of both the men and women reported non-arousal and partnered-arousal OSA experience. Whereas the majority of the men reported solitary-arousal experience, a minority of the women reported this type of experience. Further, across all types of OSAs, individuals who reported engaging in the activities did so infrequently, with the highest average frequency being less than once a week. In comparison, recent statistics suggest that 93% of American adults aged 18–29 use the Internet and this age group dominates use for all areas of life including daily activities such as online banking, etc. (PEW Internet and American Life Project, 2009, 2010).

This study extended previous research on OSA by demonstrating that men and women differ on some but not all types of OSAs. We found support for our predictions, based on the TSS, that a similar percentage of men and women would report that they had engaged in non-arousal OSA and at a similar frequency. This finding suggests that gender socialization does not produce different sexual scripts for men and women with respect to seeking sexual information and dating relationships online. Also consistent with the TSS, about twice as many men than women reported solitary-arousal OSA experience. Further, among the subsample of men and women who had engaged in solitary-arousal OSA, the men reported doing so more frequently than did the women. Thus, consistent with previous research findings for online and offline pornography use (Traeen et al., 2006), the findings suggest that solitary-arousal activities are a more acceptable part of sexual expression for men than for women. An alternative explanation is that women participate in solitary-arousal OSA less frequently than men because they find these activities less subjectively and/or physiologically sexually arousing or pleasurable (Allen et al., 2007).

Similarly, about twice as many men than women reported partnered-arousal OSA experience. This finding indicates that partnered-arousal OSA fits with the TSS prescription that less mainstream sexual behaviors are more acceptable for men than for women. Further, it suggests that heterosexual men’s frequency of engaging in partnered-arousal OSA was limited by the low number of women who participate in partnered-arousal OSA. If this is the case, we would expect that men who have sex with men would report higher frequencies of engaging in partnered-arousal OSA than would exclusively heterosexual men. Indeed, Traeen et al. (2006) found that gay and bisexual men reported more erotic chatting than heterosexual men. However, it is also possible that the gender difference in incidence of partnered-arousal OSA is an artefact of gender norm responding, similar to offline reports (Alexander & Fisher, 2003). Nonetheless, the men and women in the present study who reported they had engaged in partnered-arousal OSA did not differ in their frequency of experience. This finding suggests that once partnered-arousal OSAs are initiated, the relational aspects of these activities fit with the TSS prescription for women’s sexual expression. It may be that women engage in partnered-arousal OSA within a real, or perceived, relationship. Indeed, past research has found that women are more likely to view sexually explicit material online with their current partners than alone whereas men are more likely to do the opposite (Traeen et al., 2006). Thus, it may be that women do not initiate OSA experiences with a partner but rather participate in response to male initiation. Past research has found that men initiate offline sexual activity more frequently than women (O’Sullivan & Byers, 1992). Future research needs to examine the context in which men and women engage in partnered-arousal OSA, including their relationship to their online partner, whether they engage repeatedly with the same person or with different people each time, and how their own relationship status influences their partnered-arousal OSA experience.

Understanding Gender Differences in OSA Experience

In keeping with past research (Baumeister et al., 2001; Peterson & Hyde, 2010), we found that men were more accepting of casual sex than women. We also found that men reported more positive attitudes toward OSA than did women. This finding was consistent with research on attitudes toward pornography (O’Reilly et al., 2007). We extended past research by examining the extent to which these accepting and positive attitudes mediate the relationship between gender and AR-OSA. We found partial support for the proposed model. Although attitude toward OSA, sexual attitudes, and acceptance of casual sex were all related to each other, only attitude toward OSA mediated the relationship between gender and AR-OSA. Indeed, sexual attitudes were not even significantly associated with AR-OSA. These findings suggest it is specific attitudes toward OSA and not sexual attitudes in general that are important in understanding men’s more frequent participation in AR-OSA.

Although we found support for the hypothesized model, other causal relationships are possible. That is, it may be that engaging in OSA results in more positive attitudes toward OSA rather than vice versa, or that the relationship is reciprocal. Additionally, we found a direct relationship between gender and frequency of AR-OSA experience that suggests there are mechanisms not assessed through which gender exerts its influence on AR-OSA experience. One such mechanism may be men’s greater comfort with computers. Researchers have found that higher computer self-efficacy is associated with more Internet use and men report both higher computer self-efficacy and more Internet usage (Jackson, Ervin, Gardner, & Schmitt, 2001).

Our findings did not support an association between offline and online sexual experience. Consistent with Boies (2002), number of offline sexual partners was not associated with frequency of AR-OSA experience. It may be that number of offline sexual partners is not a good indicator of the aspects of offline sexual activity that are most pertinent to understanding how OSA fits into a larger repertoire of sexual behavior. For example, Traeen et al. (2006) found that experience with group sex, an unconventional sexual activity, predicted experience with viewing pornography online and with erotic chatting. Because arousal-oriented OSAs are not widely experienced, they are not conventional forms of sexual activity. Thus, it may be specifically experience with unconventional offline sexual activity that is key for understanding the association between online and offline sexual experience. Alternatively, it may be that experience with specific offline sexual activities are associated with a parallel experience online but that general sexual experience does not predict general OSA experience. This alternative is consistent with research that has found a connection between more offline sex partners and more online sex partners as well as between viewing sexually explicit material offline and online (Byers et al., 2004; Daneback, Cooper, & Månsson, 2005). If so, to fully understand the association between offline and online sexual experience researchers may need to examine specific types of sexual interests, fantasies, and behaviors.

Limitations and Conclusions

This study is not without its limitations. The results may not generalize to more diverse samples because participants were generally young, heterosexual, and of white European descent. This limitation is particularly important with respect to generalizing to sexual minority groups because the Internet likely plays a different role for these individuals than for heterosexual individuals (e.g., facilitating social supports and the coming out process; Heinz, Gu, Inuzuka, & Zender, 2002). In addition, our use of self-report measures may have introduced socially desirable responding which could have resulted in an underestimation of the actual frequency of OSAs because these activities are unconventional thus unlikely to be socially desirable. Additionally, as suggested by previous research (e.g., Wiederman, 1999), the participants who volunteered for this study may have more liberal sexual attitudes than those who did not volunteer to participate. This may be particularly true for the women and may have resulted in an underestimation of gender differences. Finally, due to a lack of validated measures, some of the measures were created specifically for this study. Thus, there is only limited evidence about their reliability and validity.

Nonetheless, this study contributes to OSA research by demonstrating the importance of examining different types of OSA experience. It also provides support for an initial model aimed at understanding factors affecting men and women’s participation in OSA. However, the OSA phenomenon is inherently intertwined in the technology of the modern world. Already, the popularity of social networking sites and avatars in virtual worlds add possible dimensions to OSA experiences that were uncommon when this study was conducted. The increasing integration of online communication into everyday life suggests that OSA will become more popular and more common place as youth develop with these technological capabilities already in place. As researchers, we will be challenged to understand how OSA experience parallels, differs from, and expands offline sexual expression—a task that may require modifications of our standard notions of sexual behavior.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 888–918.

Albarracin, D., Johnson, B. T., Fishbein, M., & Muellerleile, P. A. (2001). Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 142–161.

Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self-reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 27–35.

Allen, M., Emmers-Sommer, T. M., D’Alessio, D., Timmerman, L., Hanzal, A., & Korus, J. (2007). The connection between the physiological and psychological reactions to sexually explicit materials: A literature summary using meta-analysis. Communications Monographs, 74, 541–560.

Baumeister, R. F., Catanese, K. R., & Vols, K. D. (2001). Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5, 242–273.

Boies, S. C. (2002). University students’ uses of and reactions to online sexual information and entertainment: Links to online and offline sexual behavior. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 11, 77–89.

Byers, E. S. (1996). How well does the traditional sexual script explain sexual coercion? Review of a program of research. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 8, 7–25.

Byers, E. S., Henderson, J., & Hobson, K. M. (2009). University students’ definitions of sexual abstinence and having sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 665–674.

Byers, L. J., Menzies, K. S., & O’Grady, W. L. (2004). The impact of computer variables on the viewing and sending of sexually explicit material on the Internet: Testing Cooper’s “Triple-A Engine”. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13, 157–169.

Cha, E. S., Doswell, W. M., Kim, K. H., Charron-Prochownik, D., & Patrick, T. E. (2007). Evaluating the theory of planned behavior to explain intention to engage in premarital sex amongst Korean college students: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 44, 1147–1157.

Cooper, A., & Griffin-Shelley, E. (2002). Introduction. The Internet: The next sexual revolution. In A. Cooper (Ed.), Sex and the Internet: A guidebook for clinicians (pp. 1–15). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Cooper, A., Morahan-Martin, J., Mathy, R. M., & Maheu, M. (2002). Toward an increased understanding of user demographics in online sexual activities. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28, 105–129.

Daneback, K., Cooper, A., & Månsson, S.-A. (2005). An Internet study of cybersex participants. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34, 321–328.

Field, G. (2009, January 5). Houston, we have a porn problem. Glamour Magazine. Retrieved February 19, 2008, from http://www.glamour.com/sex-love-life/2009/01/houston-we-have-a-porn-problem?currentPage=4.

Gagnon, J. H., & Simon, W. (1973). Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Ganesalingam, K., Sanson, A., Anderson, V., & Yeates, K. O. (2007). Self-regulation as a mediator of the effects of childhood traumatic brain injury on social and behavioral functioning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 13, 298–311.

Goodson, P., McCormick, D., & Evans, A. (2001). Searching for sexually explicit materials on the internet: An exploratory study of college students’ behavior and attitudes. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 30, 101–118.

Heinz, B., Gu, L., Inuzuka, A., & Zender, R. (2002). Under the rainbow flag: Webbing global gay identities. International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies, 7, 107–123.

Hudson, W. W., Murphy, G. J., & Nurius, P. S. (1983). A short-form scale to measure liberal vs. conservative orientation toward human sexual expression. Journal of Sex Research, 19, 258–272.

Jackson, L. A., Ervin, K. S., Gardner, P. D., & Schmitt, N. (2001). Gender and the Internet: Women communicating and men searching. Sex Roles, 44, 363–379.

Ku, L., Sonenstein, F. L., Lindberg, L. D., Bradner, C. H., Boggess, S., & Pleck, J. H. (1998). Understanding changes in sexual activity among young metropolitan men: 1979–1995. Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 256–262.

Lopez, P. A., & George, W. H. (1995). Men’s enjoyment of explicit erotica: Effects of person-specific attitudes and gender-specific norms. Journal of Sex Research, 32, 275–288.

O’Reilly, S., Knox, D., & Zusman, M. E. (2007). College student attitudes toward pornography use. College Student Journal, 41, 402–406.

O’Sullivan, L. F., & Byers, E. S. (1992). College students’ incorporation of initiator and restrictor roles in sexual dating interactions. Journal of Sex Research, 29, 435–446.

Peterson, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 21–38.

PEW Internet and American Life Project. (2009, December 4). Trend data. Retrieved March 23, 2010, from http://www.pewinternet.org/Trend-Data/Online-Activities-Daily.aspx.

PEW Internet and American Life Project (2010, January 6). Demographics of internet users. Retrieved March 23, 2010, from http://pewinternet.org/Static-Pages/Trend-Data/Whos-Online.aspx.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Rye, B. J., & Meaney, G. J. (2007). The pursuit of sexual pleasure. Sexuality and Culture, 11, 28–51.

Schwartz, P., & Rutter, V. (2000). The gender of sexuality: Sexual possibilities (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Simpson, J. A., & Gangestad, S. W. (1991). Individual differences in sociosexuality: Evidence for convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 870–883.

Spector, I. P., Carey, M. P., & Steinberg, L. (1996). The Sexual Desire Inventory: Development, factor structure, and evidence of reliability. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 22, 175–190.

Traeen, B., Nilsen, T. S., & Stigum, H. (2006). Use of pornography in traditional media and on the Internet in Norway. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 245–254.

Wiederman, M. W. (1999). Volunteer bias in sexuality research using college student samples. Journal of Sex Research, 36, 59–66.

Wiederman, M. W. (2005). The gendered nature of sexual scripts. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 13, 496–502.

Yost, M. R., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2006). Gender differences in the enactment of sociosexuality: An examination of implicit social motives, sexual fantasies, coercive sexual attitudes, aggressive sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 163–173.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this research were conducted with the support of funding from a Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada Doctoral Fellowship to the first author and under the supervision of the second author. The data for this study were collected by the third author in partial fulfillment of her Honours thesis under the supervision of the second author. The authors would like to thank members of the Human Sexuality Research Group at the University of New Brunswick, particularly Susan Voyer and Hillary Randall, for their help with data collection and data entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shaughnessy, K., Byers, E.S. & Walsh, L. Online Sexual Activity Experience of Heterosexual Students: Gender Similarities and Differences. Arch Sex Behav 40, 419–427 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9629-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9629-9