Abstract

Deriving self-worth from romantic relationships (relationship contingency) may have implications for women’s sexual motives in relationships. Because relationship contingency enhances motivation to sustain relationships to maintain positive self-worth, relationship contingent women may engage in sex to maintain and enhance their relationships (relational sex motives). Using structural equation modeling on Internet survey data from a convenience sample of 462 women in heterosexual and lesbian relationships, we found that greater relationship contingency predicted greater relational sex motives, which simultaneously predicted both sexual satisfaction and dissatisfaction via two distinct motivational states. Having sex to improve intimacy with one’s partner was associated with greater sexual satisfaction and autonomy, while having sex to earn partner’s approval was associated with sexual dissatisfaction and inhibition. While some differences exist between lesbian and heterosexual relationships, relationship contingency had sexual costs and benefits, regardless of relationship type.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When individuals stake their self-esteem on specific domains (i.e., their self-esteem is contingent upon success in a certain domain of life), they increase their effort to pursue and maintain positive self-worth in these domains (Crocker & Park, 2004). For example, people who base their self-esteem on academics tend to spend more time studying while those who are contingent on their physical appearance spend more time grooming and tending to their appearance (Crocker & Luhtanen, 2003). Although having contingencies of self-worth (CSWs) increases motivation and effort in the contingent domains, CSWs also have costs for learning, relationships, and well-being because attempts to validate the self often backfire and increase feelings of inauthenticity (Crocker & Knight, 2005; Crocker & Park, 2004; Park & Crocker, 2005). Thus, while CSWs may be motivating, they may simultaneously be debilitating. No research that we know of has examined the role of CSWs in shaping motivation in sexual relationships yet the pursuit of self-esteem through romantic relationships may affect when and why individuals engage in sexual activities with their partner.

Relationship Contingent Self-Worth

Contingencies of self-worth theory suggests that motives are shaped not so much by level of self-esteem but rather by domains on which self-esteem is based (Crocker & Knight, 2005). Research on contingencies of self-worth examines the extent to which people base their self-esteem in various domains as well as the cognitive, affective, and behavioral consequences of staking self-worth in these various domains. People who have relationship contingent self-worth (Relationship CSW) base their self-esteem on maintaining their romantic relationships (Knee, Canevello, & Bush, 2008; Sanchez & Kwang, 2007). Because self-worth is tied to their romantic relationships, people who have Relationship CSW experience greater emotional responses to changes in their relationships (Knee et al., 2008; Park, Sanchez, & Brynildsen, in press). For example, relationship contingent individuals experience greater drops in self-esteem and increases in distress when negative events happen in their relationships and greater increases in self-esteem when positive events occur than those who are less relationship contingent (Knee et al., 2008; Park et al., in press). Relationship CSW also increases behaviors aimed at preserving and maintaining one’s romantic relationship (Sanchez & Kwang, 2007). People with Relationship CSW may attempt to achieve their relationship goals through their sexual relationship because sexual satisfaction is thought to (and may actually) improve relationship satisfaction (Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Edwards & Booth, 1994). The more people base their self-worth on their romantic relationships, the more they may be motivated to have sex to preserve their romantic relationship rather than, for example, their own pleasure.

Greater motivation to preserve romantic relationships as result of Relationship CSW leads to both positive and negative outcomes for romantic relationships and the self. For example, relationship contingent people are more focused and attentive to their partners than those who are less contingent; however, the added attention towards their partners may make relationship contingent individuals obsessively pursue their partners after their relationships have ended (Park et al., in press). Moreover, relationship contingent individuals report greater levels of commitment to their relationships than those who are not relationship contingent (Knee et al., 2008). However, this greater level of commitment does not necessarily translate into more satisfying relationships (Knee et al., 2008). In fact, the fear of being without a romantic partner may keep relationship contingent individuals in unsatisfying relationships for longer periods of time (Sanchez, Good, Kwang, & Saltzman, 2008).

Relational Sex Motives

Contingency of self-worth theory suggests that goal pursuit within contingent domains can be costly because increased motivation and effort in contingent domains does not always translate into goal attainment (see Crocker & Park, 2004). Likewise, Relationship CSW may lead to greater sexual motivation aimed at maintaining or enhancing relationships with partners (relational sex motives) with mixed results for the sexual relationship. Specifically, sexual motivations that focus on maintaining the relationship may lead to divergent outcomes for sexual satisfaction depending on whether the desire to have sex stems from the need for partner’s approval or from a desire to enhance intimacy. To explore this possibility, we examined two distinct types of sexual motivation that could potentially result from Relationship CSW.

Theories of sexual motivation suggest that sexual motivation may be better understood by determining whether behaviors are driven by the pursuit of pleasurable outcomes (appetitive behaviors) or the avoidance of negative outcomes (aversively motivated behaviors; Cooper, Shapiro, & Powers, 1998; Impett, Gable, & Peplau, 2005). Within this framework, relational motives may involve the desire to create positive outcomes in relationships such as intimacy and closeness (intimacy motives) or the desire to avoid negative outcomes such as disapproval from one’s partner (approval sex motives). People who base their self-worth on their relationships may be even more motivated than others to avoid negative relationship outcomes (e.g., breakups and unhappy partners) and create positive relationship experiences (e.g., long-term relationships), given the consequences for their self-worth.

Thus, the consequences of relational sex motives may diverge, depending on whether behavior is driven by the desire to create intimacy eliciting appetitive behaviors or the desire to avoid disapproval eliciting aversively driven behaviors. If people engage in sexual behavior primarily in an effort to gain their partner’s approval (approval sex motives), they are unlikely to express their own sexual desires and therefore feel less sexually autonomous, which can lead to more unwanted sexual behavior, lower psychological well-being and decreased relationship satisfaction over time (Cooper et al., 1998; Impett & Peplau, 2003; Impett et al., 2005). People who are sexually autonomous feel as though their sexual behaviors are volitional, chosen, and self-determined (Kiefer & Sanchez, 2007). Thus, approval sex motives may dampen sexual autonomy and satisfaction. This may be particularly true of women, who are more likely than men to engage in unwanted and passive sexual behavior, which impedes sexual functioning and satisfaction (O’Sullivan & Algeier, 1998; Sanchez, Kiefer, & Ybarra, 2006). In contrast, women who are motivated to engage in sexual behavior to enhance intimacy with their partner may have more satisfying sexual experiences. Unlike approval sex motives where external forces (i.e., identifying and satisfying the partner’s needs) guide behavior, internal desires for connection and relatedness drive sexual encounters for those with intimacy motives (Cooper et al., 1998). As a result, intimacy motives predict greater daily psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction (Impett et al., 2005). Therefore, women who are motivated to enhance the intimacy in their relationship may be more likely to express their sexual desires, and succeed in having them met.

Exploring Moderators

Given that Relationship CSW may encourage relational sexual motives with divergent outcomes for relationships, it is important to explore when Relationship CSW may be more likely to promote intimacy motives or approval motives. Individuals who have Relationship CSW may also be more likely to base their self-esteem on the approval of others (Approval CSW). In other words, romantic relationships may be one of many social sources of self-esteem. Approval CSW is related to lower and more unstable self-esteem as well as less satisfaction in relationships (Crocker, 2002; Crocker, Luhtanen, Cooper, & Bouvrette, 2003; Kernis, 2003; Sanchez, Crocker, & Boike, 2005). Those who are higher in Approval CSW may have more dependent personalities which may lead to an exaggerated reliance on others for emotional support, lack of confidence and feelings of powerlessness (Bornstein, 1993). Relationship CSW may be less likely to lead to motives aimed at creating positive relationships and more likely to promote approval sex motives when combined with high Approval CSW. The consequences of Relationship CSW may also depend on aspects of the romantic relationship such as the quality or length of the relationship. Basing self-worth on a more satisfying relationship or long-term relationship may lend itself to intimacy sexual motives when the relationship is already moving in a positive direction while basing self esteem on an unsatisfying relationship or a short-term relationship may lend itself to greater approval sexual motives. Long term relationships may alleviate concerns about relationship loss among individuals with Relationship CSW while those in the early stages of relationships may make more compromises for the sake of relationship conservation such as unwanted sexual behavior.

A Model for Women in Lesbian or Heterosexual Relationships

We focus on women in the present study for several reasons. First, research suggests that women, on average, are less sexually satisfied than men (e.g., Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999); thus, it is crucial to understand the predictors of women’s sexual satisfaction. Second, women are socialized to prioritize personal relationships so much so that their desire to maintain relationships may become internalized in the self (Cross & Madson, 1997; Sanchez & Kwang, 2007). Thus, women’s relationship contingency may be a stronger predictor of women’s behaviors and strivings within the relationship than men’s.

Several theories suggest that the dynamics in heterosexual relationships may account for women’s difficulty negotiating autonomy and power in sexual relationships (MacKinnon, 1987; Rubin, 1990). For example, researchers argue that women face added pressure and obstacles when negotiating safe sex with male partners due to unequal power dynamics between men and women (Holland, Ramazanoglu, Scott, Sharpe, & Thomson, 1992). Moreover, men report greater sexual desire and interest than women (Baumeister, Catanese, & Vohs, 2001); thus, disparities in sexual desire may be unique to male–female relationships and drive some of the links between approval sex motives and sexual outcomes. Thus, we included women who were in relationships with other women to test whether this model would hold for relationships that are not as prone to unequal power dynamics and disparities in desire.

Overview of the Present Study

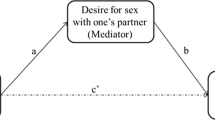

In the present study, we test a model of sexual satisfaction with the following paths: (1) Women’s relationship contingency predicts greater relational sexual motivation (e.g., higher intimacy sex motives and approval sex motives); (2) relational sexual motivations will predict sexual autonomy and satisfaction, such that inti macy sex motives predict greater sexual autonomy and satisfaction while approval sex motives predict lower sexual autonomy and satisfaction; (3) consistent with previous research (Kiefer & Sanchez, 2007; Sanchez et al., 2005, 2006), we expected greater sexual autonomy to predict greater sexual satisfaction. The predictions are shown in Fig. 1. Lastly, we conduct some exploratory analyses to examine whether relationship satisfaction, length, and approval contingency affects whether relationship contingency is associated with intimacy sex motives or approval sex motives.

Method

Participants

We utilized cross-sectional data from a convenience sample of women currently involved in romantic relationships who were recruited over the Internet from various Yahoo® groups and local email lists serving women, women’s groups, women’s hobbies, and the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis, no compensation was given. Data were collected from individuals, not couples. The Internet survey was active for 10 months from January 2005–October 2005. Internet research utilizing convenience samples is common (Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2004), especially with research on gay and lesbian participants (Harry, 1990; Konik & Stewart, 2004; Sell, 1996). This type of sampling is utilized because gay and lesbian participants are often difficult to find, representing a relatively small percentage of the population. Although this type of sampling may be limited by non-representativeness, other methods are impractical (see Harry, 1990; Konik & Stewart, 2004).

We took several additional precautions to enhance the reliability of the results. For example, the demographic page directly followed the informed consent and assessed whether participants were eligible for the survey. If participants were not women in relationships, they were exited from the survey, thanked for their time, and blocked from entering the survey again. Moreover we prevented multiple responses from the same computer using cookies (Eysenbach, 2004). Questions appeared on several different pages. Time spent on each page of the survey was recorded. We created time cutoffs for each page based on the number of questions on the page. Participants exceeding 60 s per question or under 1-s per question warranted removal from the data. The average time participants took to complete the survey was 21.14 min. Participants could skip any question at any time as well as exit the entire survey at any point. Forty participants were not included in the analyses because of incomplete data, violating time constraints, or not being in romantic relationships (9% of the data).

The final sample included 300 participants currently involved in heterosexual relationships and 159 currently involved in lesbian relationships. The racial background of the participants was as follows: 372 Whites (81%), 28 Black/African American (6%), 24 Multiracial Americans (5%), 20 Asians/Asian American (4%), 16 Hispanic/Latinos (3%), 1 Native American (~1%), and 1 who did not indicate a racial background (~1%). Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 62 years (M = 29.57, SD = 9.56). The majority of our sample indicated an income of “Under $25, 000” (N = 236; 51%) or “Between $25,000 and $50,000” (N = 147; 32%). The rest of the sample indicated incomes above $51,000 (N = 70; 15%) or comprised missing data (N = 6; 2%). The majority of our sample estimated their partner’s income at “Under $25, 000” (N = 171; 37%) or “Between $25,000 and $50,000” (N = 146; 32%). The rest of the sample indicated partners’ incomes above $51,000 (N = 139; 31%) or comprised missing data (N = 3; ~1%). The majority of the participants indicated either having completed college (N = 117; 26%) or having complete some post-college graduate education (N = 212; 46%). The rest of the sample either had some high school or college education (N = 129; 28%) or comprised missing data (N = 1; ~1%).

Participants indicated an average length of relationship of 1–3 years. Fifty-six percent indicated currently living with their romantic partners (N = 259). The majority of the sample (N = 375; 75%) indicated that they did not have any children while 45 (10%) indicated 1 child, 35 (7%) indicated 2 children, 19 (4%) indicated 3 children, 12 (2%) indicated 3 children, and 4 (1%) indicated 4 or more children. Our entire sample was sexually experienced (i.e., had previously engaged in sexual activities such as giving/receiving oral sex or vaginal penetration). We report on a subset of the measures administered in the Internet survey. Ethical approval was obtained for all aspects of the study design.

Measures

The Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale (CSWS; Crocker et al., 2003) was administered with the Relationship Contingency subscale. The CSWS contains seven other subscales: competition contingency, approval contingency, appearance contingency, religious faith contingency, virtue contingency, and work/academic contingency. Relationship contingency was assessed with four items from Sanchez and Kwang (2007) measuring the extent to which women based their self-esteem on having a romantic relationship: (1) “When I do not have a significant other (i.e., boyfriend or girlfriend), I feel badly about myself”; (2) “I feel worthwhile when I have a significant other”; (3) “When I have a significant other (i.e., boyfriend or girlfriend), my self-esteem increases”; and (4) “My self-esteem depends on whether or not I have a significant other (i.e., boyfriend or girlfriend)”. Participants indicated agreement on a 7-point scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). The scale was reliable for women in lesbian relationships (α = .83) and heterosexual relationships (α = .74).

Approval sex motives were measured using the Sexual Motivation Scale developed by Cooper et al. (1998). The measure assessed how often women were motivated to have sex to avoid partners’ disapproval and attain their acceptance on a scale from 1 (Almost Never/Never) to 5 (Almost Always/Always). The following items were used: (1) “How often do you have sex out of fear that your partner won’t love you anymore if you don’t?”; (2) “How often do you have sex because you don’t want your partner to be angry with you?”; and (3) “How often do you have sex because you’re afraid that your partner won’t want to be with you if you don’t?” The scale was adequately reliable for lesbian relationships (α = .67) and heterosexual relationships (α = .77).

Intimacy sex motives were measured using the Sexual Motivation Scale developed by Cooper et al. (1998). The measure assessed how often women were motivated to have sex to enhance intimacy with their partner on a scale from 1 (Almost Never/Never) to 5 (Almost Always/Always). The following items were used: (1) “How often do you have sex to become more intimate with your partner?” (2) “How often do you have sex to express love for your partner?” and (3) “How often do you have sex to make an emotional connection with your partner?” The scale was reliable for lesbian relationships (α = .89) and heterosexual relationships (α = .90).

Sexual autonomy was measured by adapting the Relationship Autonomy Scale (LaGuardia, Ryan, Couchman, & Deci, 2000). The same measure was used and found reliable in previous research (Kiefer & Sanchez, 2007; Sanchez et al., 2005, 2006). The following items were included: (1) “In my sexual relationship with my partner, I feel free to be who I am,” and (2) “In my sexual relationship with my partner, I have a say in what happens and can voice my own opinion.” Participants indicated their agreement with each statement on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Disagree). The scale was found to be reliable for women in lesbian relationships (α = .78) and heterosexual relationships (α = .77).

Sexual satisfaction was measured with two items taken from Sanchez et al. (2005). Participants responded on a scale from 1 (Never) to 6 (Always) to the following items: (1) “I usually find sex to be completely satisfying,” and (2) “I usually find sex to be very exciting with my partner.” This scale was reliable for lesbian relationships (α = .86) and heterosexual relationships (α = .84).Footnote 1

Several measures were included as potential control variables for our model. For example, social desirability was assessed using the 32-item Marlowe–Crowne scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960; α = .92). In addition, religiosity was measured with three items (α = .84). Participants were asked, “How religious are you?” on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Very). Participants were also asked, “How often do you attend religious services?” and “How often do you pray” on a scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very Regularly). Finally, participants were asked “How often do you engage in sexual activities with your partner?” on a scale from 1 (less than once a month) to 6 (5 or more times a week) to serve as a measure of sexual frequency.Footnote 2 Relationship satisfaction was assessed with two subscales (satisfaction and communication) based on previous research (Kiefer & Sanchez, 2007; Murray, Bellavia, Feeney, Homes, & Rose, 2001). The satisfaction subscale consisted of three items based on Murray et al. Participants indicated their agreement on a 7-point scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree) with the following statements: (1) “I am extremely happy with my romantic relationship,” (2) (reverse-coded) “I do not feel that my relationship is successful,” and (3) “I have a very strong relationship with my partner.” The subscale was reliable for lesbian (α = .88) and heterosexual participants (α = .89). The communication scale consisted of the following items: (1) “I am satisfied with the level of communication in my relationship with my romantic partner,” (2) “I talk to my partner about everything, even topics that make me uncomfortable,” and (3) “I communicate well with my partner even when the topic is upsetting.” The scale was reliable for lesbian (α = .79), and heterosexual relationships (α = .77). The satisfaction and communication scales were used as indicators of overall satisfaction in the model (r = .76, p < .001), and the combined scale was reliable for lesbian relationships (α = .90) and heterosexual relationships (α = .90).

Moderator Variables

Approval contingency was assessed with four items from CSWS measuring the extent to which people based their self-esteem on having other’s approval: (1) (reverse-coded) “I don’t care if other people have a negative opinion of me”; (2) (reverse-coded) “I don’t care what other people think of me”; (3) (reverse-coded) “What others think of me has no effect on what I think about myself”; and (4) “My self-esteem depends on the opinions others hold of me.” Participants indicated agreement on a 7-point scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). The scale was reliable for women in lesbian relationships (α = .87) and heterosexual relationships (α = .88). Relationship Length was measured on a scale from where 1 = less than a month, 2 = 1–6 months, 3 = 6–12 months, 4 = 1–3 years, 5 = 3–6 years, 6 = 6–10 years, and 7 = over 10 years.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the means and SDs as well as any significant differences between those who had a female partner at the time of the survey as compared to those who had a male partner at the time of the survey. As shown in Table 1, women in lesbian relationships indicated greater sexual satisfaction but a lower sex frequency than women in heterosexual relationships. In addition, women in lesbian relationships were less religious than women in heterosexual relationships. Tables 2 and 3 show the zero-order correlations for the entire sample of women and then separately by gender of partner.

To assure that relationship contingency was the strongest predictor of sexual motives compared to all the other external contingencies of self-worth (other’s approval contingency, competition contingency, academic/work contingency, appearance contingency), we regressed intimacy sex motives and approval sex motives (separately) on all of the external contingencies of self-worth separately. Relationship contingency was the only predictor of intimacy motives (β = .19, p < .01) and approval sex motives (β = .10, p < .05).

To ensure that the links between Relationship CSW, sexual goals, sexual autonomy, and sexual satisfaction persisted when controlling for variables known to affect responses to sexual questions (e.g., social desirability) and sexual experiences (e.g., relationship length), we conducted preliminary regression analyses. We regressed sexual satisfaction on several demographic variables (living with partner, education, income, partner’s income, parental status, length of relationship) and potential control measures (social desirability, religiosity, sex frequency, relationship satisfaction). Social desirability was unrelated to sexual satisfaction. Although modest relationships were found between sexual satisfaction and education (r = −.13, p < .01), length of relationship (r = −.19, p < .001), personal income (r = .11, p < .01), and sexual activity frequency (r = .28, p < .001), adding these predictors did not improve—and indeed often hampered—the fit of the model. However, relationship satisfaction was a strong and theoretically important predictor of sexual satisfaction and thus was added to the hypothesized model (see Fig. 2). Relationship satisfaction was important to include in the model because approval sex motives, which include motives to avoid dissatisfied partners, may be more likely among those with dissatisfying relationships. Thus, approval sex motives may be conflated to some degree with lower relationship satisfaction. For this reason, it was important to account for the variance in relationship satisfaction when estimating the paths between approval sex motives, sexual autonomy, and sexual satisfaction.

Structural Equation Modeling Analyses

The model was tested with confirmatory latent variable structural analyses using EQS computer software. Essentially, this analysis allows researchers to test several regression equations simultaneously while also testing the factor structure of the items. In doing so, the analyses take into account measurement error while estimating the significance of the paths between variables. For example, the measurement error estimated for the underlying factor of Relationship CSW will affect the significance of the path from Relationship CSW and sexual goals. To perform structural equation modeling, the researchers must first determine the measurement model by deciding which items will serve as indicators for each factor and assessing the fit of the measurement model.

In the measurement model, each item was used an indicator of the underlying factor except for relationship contingency and relationship satisfaction. So, for example, the two questions about sexual satisfaction were used as the indicators of the underlying factor of sexual satisfaction. Because many items comprised the Relationship CSW and relationship satisfaction scales, which would require an even larger sample size, we chose to combine some items from each scale into two indicators of the underlying factor, a method called parceling. For Relationship CSW, we randomly selected two items and used their averages to serve as the two parcels. The two subscales served as indicators of relationship satisfaction. Parceling is a common procedure in structural equation modeling, which reduces bias in estimates, allows for testing of models with smaller sample sizes, and corrects for non-normality in data (Bandalos, 2002; Bandalos & Finney, 2001; Marsh, Hau, Balla, & Grayson, 1998). In some cases, however, parceling can lead to inaccurate results if the structure of the factor is not unidimensional (see Hall, Snell, & Singer-Foust, 1999); this was not the case for the factors in our model.

In the following analyses, the structural model was tested on the entire sample, and separately for women who were currently involved in lesbian and heterosexual relationships. The structural models were performed on listwise covariance matrices. In accordance with standard structural equation modeling reporting with EQS software (Raykov, Tomer, & Nesselroade, 1991), the following goodness-of-fit indices are reported: non-normed fit (NNFI) and comparative fit (CFI). Acceptable fit indices exceeded .90. We also reported the root MSE of approximation (RMSEA) as well as the confidence interval of the RMSEA. RMSEA misfit indices should be at or below .06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). χ2 is reported, but has been replaced by the previously-mentioned fit indices because of its sensitivity to sample size (Klem, 2000). χ2 is instead used to compare the fit of nested models (e.g., comparisons between the model fit for women in lesbian and heterosexual relations). Akaike information criterion (AIC) is reported and used to compare the fit of alternative models (Kline, 2005). We used listwise case deletion to handle missing data. Twenty-eight participants had incomplete data and were excluded from the structural equation modeling analyses. We used the Lagrange multiplier test to determine what paths to include in the model between relationship satisfaction and the other variables. The Lagrange multiplier test estimates the amount of change in χ2 that would result if a path was added between two underlying factors (Hoyle, 1995).

Testing the Hypothesized Model on the Full Sample

The measurement model provided a good fit to the data, suggesting that we could proceed to test the hypothesized model (see Table 4). The hypothesized structural model based on the total sample also provided a good fit to the data (see Table 4). As shown in Fig. 2, the overall model explained 54% of the variance in sexual satisfaction and 43% of the variance in sexual autonomy. As predicted, relationship CSW predicted greater relational sex motives (greater intimacy motives and approval sex motives). Also as expected, intimacy sex motives predicted greater sexual autonomy and satisfaction while approval sex motives predicted less sexual autonomy and satisfaction. Sexual autonomy predicted greater sexual satisfaction. Relationship satisfaction predicted greater sexual autonomy, less approval motivation, and more intimacy motivation, but unexpectedly did not directly predict sexual satisfaction.

Testing the Hypothesized Model by Gender of Partner

To test the comparative fit of the model by gender of partner, the fit of the covariance matrices was tested for both groups separately, constraining all paths to be equal. The fully restrained model provided a good fit to the data (see Table 4). Examination of the modification indices and releasing constraints did not improve the fit of the model. In addition, the hypothesized model was not significantly different from the unrestrained model, χ2(13) = 15.72, ns, suggesting that post hoc constraints should not be released.

Relationship CSW predicted relational sexual motivation: greater intimacy sex motives for women in lesbian relationships (β = .23) and heterosexual relationships (β = .20) and greater approval sex motives for women in lesbian relationships (β = .13) and heterosexual relationships (β = .13). Greater approval sex motives predicted less sexual autonomy for women in lesbian relationships (β = −.27) and heterosexual relationships (β = −.24). More intimacy motives predicted greater autonomy for both women in heterosexual (β = .12) and lesbian relationships (β = .12). Sexual autonomy was associated with greater sexual satisfaction for women in lesbian relationships (β = .55) and heterosexual relationships (β = .51). Moreover, relationship satisfaction predicted greater sexual autonomy, greater intimacy motivation, and lower approval motivation but not sexual satisfaction for both groups.

Testing the Hypothesized Model Against Alternative Models

Although we cannot confirm the causal paths in the model given the correlational nature of this study, we did test a series of plausible alternative models to compare with our full hypothesized model. The results for the alternative models appear in Table 4. In the alternative models, relationship satisfaction was always a predictor of sexual autonomy and satisfaction. In Alternative Model 1, we examined the possibility that relational sex motives may influence sexual autonomy and satisfaction, which then contribute to relationship contingency (i.e., Relational Sex Motives → Sexual Autonomy → Sexual Satisfaction → Relationship CSW), because people may become relationship contingent depending on the quality of their intimacy with their partner. However, Alternative Model 1 had a higher AIC and RMSEA and thus proved a worse fit to the data than the hypothesized model.

In Alternative Model 2, we examined the possibility that relational sex motives may influence relationship contingency, which then affect sexual autonomy and satisfaction (i.e., Relational Sex Motives → Relationship CSW → Sexual Autonomy → Sexual Satisfaction), because people may intuit that they are relationship contingent by the relational nature of their sexual motives. Alternative Model 2 also had a higher AIC and RMSEA and thus proved a worse fit to the data than the hypothesized model.

In Alternative Model 3, we completely reversed the hypothesized model to test whether sexual satisfaction influences sexual autonomy, which then influences relational sex motives and relationship contingency (i.e., Sexual Satisfaction → Sexual Autonomy → Relational Sex Motives → Relationship CSW). However, Alternative Model 3 also had a higher AIC and RMSEA and thus, proved a worse fit to the data than the hypothesized model. Thus, none of the alternative models provided a better fit to the data.

Testing for Moderators of the Path Between Relationship Contingency and Relational Sex Motives

To explore whether relationship length, relationship satisfaction, or approval contingency moderated the link between Relationship CSW and relational sex motives, we ran regression analyses following the method of examining interactions and simple effects recommended by Aiken and West (1991). First, we regressed intimacy sex motives and approval sex motives (separately) on Relationship CSW, Relationship Satisfaction, and the product of Relationship CSW and Relationship. The interaction term was not significant in either analysis, suggesting that Relationship Satisfaction did not moderate these effects. We conducted the same analyses with length of relationship as a moderator. The interaction was significant for approval sex motives (β = −.10, p < .05; see Fig. 3). Simple slopes analysis revealed that Relationship CSW predicted greater approval sex motives for those in shorter relationships (β = .25, p < .001), not for those in longer relationships (β = .04). No interaction was found for intimacy sex motives. We conducted the same analyses with approval contingency as a moderator. The interaction was marginally significant for intimacy motives (β = −.09, p = .06; see Fig. 4). Simple slopes analysis revealed that Relationship CSW predicted greater intimacy sex motives for those lower in approval contingency (β = .22, p < .01), not for those higher in approval contingency (β = .06). No interaction was found for approval sex motives.

Discussion

Consistent with predictions, Relationship CSW was linked to increased relational sex motives. On the one hand, relationship contingency predicted greater intimacy sex motives, which was related to greater sexual autonomy and satisfaction. On the other hand, relationship contingency predicted greater approval sex motives, which hindered sexual autonomy and satisfaction. Moreover, the results suggested that the gender of women’s partners did not moderate the results. We found preliminary evidence, however, that the length of relationship and one’s generally tendency to seek other’s approval to maintain self-worth may affect whether relationship contingency predicts intimacy sex motives or approval sex motives. When individuals were generally less approval seeking in their social relationships, Relationship CSW predicted greater intimacy sex motives. When individuals were at the beginning of their relationships, Relationship CSW predicted greater approval sex motives. This work adds to a growing literature on the motivating nature of contingencies of self worth as well as the costs and benefits of CSWs for relationships (Crocker & Luhtanen, 2003; Park & Crocker, 2005; Sanchez et al., 2005).

This work also builds on previous work suggesting that relationship contingency, specifically, may be damaging for close relationships (Knee et al., 2008; Park et al., in press). To maintain their romantic relationships and their partners’ happiness in the beginning of their relationships, relationship contingent women may engage in sexual activities at the expense of their own sexual autonomy and satisfaction. Relationship contingent women may be more likely to have approval sex motives in the beginning of relationships because, at early stages in the relationship, they may not feel secure in the longevity of their relationships. Thus, the possibility of losing the relationship and the resulting threat to self-esteem may motivate relationship contingent women to engage in activities that they feel will repair or maintain their partner’s happiness in and out of the bedroom.

Although women may have sex to gain their partner’s approval and preserve their relationships, it is unclear whether sex approval motives actually lead to satisfactory sexual experiences for their partners. In future studies, research should examine whether individual sexual satisfaction is affected by the sexual goals of their partners. People in relationships likely sense when their partners are having an autonomous and sexually satisfying experience, which can affect their own sexual satisfaction (Dunn, Croft, & Hackett, 2000). Therefore, sex approval motives may not achieve their intended purpose of pleasing partners.

In addition to the work suggesting that relationship contingency may lead to negative relationship outcomes (Knee et al., 2008; Sanchez & Kwang, 2007; Sanchez et al., 2008), relationship contingency was associated with greater commitment to relationships, regardless of relationship quality (Knee et al., 2008). In the present study, we found that Relationship CSW was associated with greater motivation to have sex to create intimacy and connection with their partners. Unlike sex approval motives, intimacy motives appeared to have a positive effect on relationships (Impett et al., 2005). Indeed, intimacy sex motives were linked to greater sexual autonomy and satisfaction for women. Greater autonomy may explain why those with intimacy sex motives tend to be less likely to engage in risky sexual behavior and more likely to have safe sex (Cooper et al., 1998; Gebhardt, Kuyper, & Greunsven, 2003). Like approval sex motives, future research should examine whether intimacy sex motives benefit both the individual and their partner.

Relationship CSW predicted intimacy sex motives primarily for those who are low in approval contingency. Generally, individuals who have less externally contingent self-worth tend to have better psychological outcomes including higher self-esteem and more positive attitudes about their bodies (Sanchez & Crocker, 2005; Sanchez & Kwang, 2007). Thus, it is not surprising that those who were less approval seeking had greater access to the benefits of Relationship CSW. When Relationship CSW is not an indicator of a general approval seeking personality, Relationship CSW may actually be good for relationships and the self.

Although we have identified some variables that may predict whether Relationship CSW leads to intimacy sex motives or approval sex motives, other individual difference variables and relationship context variables may moderate the effect of Relationship CSW on sexual relationships. While relationship satisfaction did not moderate the effect of relationship contingency on sexual outcomes, perceived satisfaction of one’s partner could influence the sexual motives of those who are relationship contingent. When relationship contingent individuals sense that their partners are unsatisfied or disapproving, they may engage in sex to regain their partner’s approval as an attempt to repair self-esteem (see Knee et al., 2008). Short relationship length, may, in part, be an indicator of low partner satisfaction although these cross-sectional data cannot address this question. Future research utilizing longitudinal design and data from couples should examine why and when relationship length and partner satisfaction interact with Relationship CSW to predict approval sex motives.

Although this research does not include clinical samples, these research findings could help in understanding some potential consequences of dependency for relationships. For example, motives (sexual or otherwise) may be informed by a tendency to derive worth from relationships. These motives may have more positive outcomes if Relationship CSW is not accompanied by a general dependence on other’s approval. Borrowing from treatments of dependent personality disorders, clinicians may want to encourage autonomous and independent thinking and behavior among their patients who are thought to be relationship contingent to encourage patients to see the self as powerful and reduce fears of abandonment (Bornstein & Bowen, 1995). Engaging in these types of treatments may improve romantic relationship experiences such as sexual outcomes among those with more Relationship CSW.

The present study also found that relationship contingency had similar costs and benefits for women in lesbian and heterosexual relationships. This suggests that the differential power dynamics that may exist between women with male and female partners does not change whether Relationship CSW predicts relational sex motives. Although women in lesbian relationships more equally divide labor and resources (e.g., Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983; Kurdek, 2003), how their self-worth is determined may play a more important role in shaping sexual motivation than unequal power dynamics. Women in heterosexual relationships did indicate having sex more often even though they indicated lower levels of sexual satisfaction compared to women in lesbian relationships. This finding suggests that women in heterosexual relationships engage in unsatisfying sex more often than lesbian women, which may reflect unequal power to refuse sexual activities in heterosexual relationships.

Although the current study examined important links between relationship contingency and sexual motives for women in lesbian and heterosexual relationships, the study has limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional, correlational design, we were unable to test causal relationships. While the proposed causal paths fit the data better than alternative causal models, we cannot rule out these alternatives completely. Moreover, some of the links between the variables of interest were modest in size, especially in comparison to the paths involving relationship satisfaction. This suggests that relationship satisfaction may play a more important role in sexual outcomes than Relationship CSW. The present research was also limited by reliance on self-report, which may be compromised by social desirability when people report sensitive topics such as sexuality (Alexander & Fisher, 2003). Notably, the measure of social desirability included in the study did not correlate with any of the variables and adding it did not improve the fit of the model; however, social desirability measures may not fully account for the effects of social desirability.

Our sample was also a convenience sample drawn from the Internet. Although many issues should be considered when evaluating Internet research, such as uncontrollable experimental conditions and representativeness, researchers suggest that samples in Internet survey research are just as representative as those in non-Internet survey research, if not more diverse than traditional methods (Gosling et al., 2004). Furthermore, Gosling et al. also found that Internet research generalizes across presentation formats, and results do not vary from traditional methods. In the present study, several precautions were taken to improve the reliability of results, such as keeping track of the length of time participants spent on the study, disallowing multiple responses from IP addresses, and recruiting from web communities that cater to women. Although the use of the Internet brings concerns, the Internet provided a great opportunity to find research participants who were sexual experienced and diverse in their sexual identifications, unlike many college samples. It is important, however, to note that our sample was predominantly White, without children, highly educated, and under thirty years of age. Thus, these findings may not represent women who do not share these characteristics.

Studying women’s sexuality has become increasingly important given that women’s sexual satisfaction still lags behind men’s (Laumann et al., 1999), but the exclusion of male participants does represent a limitation. Men, for example, may be less relationship contingent and generally less likely to have relational sex motives than women (Carrol, Volk, & Hyde, 1985; Leigh, 1989; Sanchez & Kwang, 2007) because they are socialized to have less interdependent and more independent construals of the self (Cross & Madson, 1997). In sexual relationships, for example, men are expected to be dominant and assertive which may explain why men are less likely to engage in unwanted sexual activity compared to women (Impett & Peplau, 2003). While Relationship CSW may predict greater relational sex motivations for men as well, it is unclear whether, for example, having approval sex motives would predict lower sexual autonomy and satisfaction if men are generally unlikely to be coerced into sexual activities. Moreover, men tend to base their self-esteem less on other’s approval than women (Crocker et al., 2003); thus, Relationship CSW may be more likely to predict intimacy motives for men.

Because gender socialization encourages women and girls to focus on and even derive self-worth from romantic relationships (Geller, Srikameswaran, & Zaitsoff, 2002; Josephs, Markus, & Tafarodi, 1992), it is important to understand whether and when Relationship CSW may be associated with positive and negative outcomes for women’s sexual relationships. On the one hand, Relationship CSW may encourage intimacy and emotional connectedness in sexual encounters when women do not also tend towards approval seeking in other relationships. On the other hand, Relationship CSW may encourage engaging in sex to avoid partner’s disapproval, especially at the beginning of relationships when longevity is uncertain. These results suggest that valuing newer relationships without basing self-worth on them may be associated with more satisfying and autonomous sexual encounters for women. Also, relationship-contingent women may experience greater sexual autonomy and satisfaction in their relationships if they are generally able to sustain self-esteem without the approval from others. The present study demonstrates how social sources of self-esteem play an important role in determining sexual motivation and therefore, sexual satisfaction.

Notes

In retrospect, the use of the word “usually” may have made this difficult for participants to interpret on a 1 (Never) to 6 (Always) scale. This represents a limitation for this measure.

Participants were also asked “How often do you engage in sexual intercourse with your partner? (i.e., vaginal penetration)”, “How often do you give oral sex to your partner?”, and “How often do you receive oral sex from your partner?” on a scale where 0 = I have never engaged in this activity and 6 = 5 or more times a week. Women in lesbian relationships indicated engaging in penetrative sex (M = 3.34) less frequently than women in heterosexual relationships (M = 3.99). No other differences on the oral sex frequencies measures were observed.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Alexander, M. G., & Fisher, T. D. (2003). Truth and consequences: Using the bogus pipeline to examine sex differences in self-reported sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 27–35.

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 78–102.

Bandalos, D. L., & Finney, S. J. (2001). Item parceling issues in structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: New developments and techniques (pp. 269–296). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Baumeister, R. F., Catanese, K. R., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 5, 242–273.

Blumstein, P., & Schwarz, P. (1983). American couples: Money, work, and sex. New York: William Morrow.

Bornstein, R. F. (1993). The dependent personality. New York: Guilford Press.

Bornstein, R. F., & Bowen, R. F. (1995). Dependency in psychotherapy: Toward an integrated treatment approach. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 32, 520–534.

Carrol, J. L., Volk, K. D., & Hyde, J. S. (1985). Differences between males and females in motives for engaging in sexual intercourse. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 14, 131–139.

Christopher, F. S., & Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage, dating and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 999–1017.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cooper, M. L., Shapiro, C. M., & Powers, A. M. (1998). Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: A functional perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1528–1558.

Crocker, J. (2002). The costs of seeking self-esteem. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 597–615.

Crocker, J., & Knight, K. M. (2005). Contingencies of self-worth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 200–203.

Crocker, J., & Luhtanen, R. K. (2003). Level of self-esteem and contingencies of self-worth: Unique effects on academic, social, and financial problems in college freshmen. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 701–712.

Crocker, J., Luhtanen, R. K., Cooper, M. L., & Bouvrette, A. (2003). Contingencies of self-worth in college students: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 894–908.

Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 392–414.

Cross, S. E., & Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 5–37.

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24, 349–354.

Dunn, K. M., Croft, P. R., & Hackett, G. I. (2000). Satisfaction in the sex life of a general population sample. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 141–151.

Edwards, J. N., & Booth, A. (1994). Sexuality, marriage, and well-being: The middle years. In A. S. Rossi (Ed.), Sexuality across the life course (pp. 223–259). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eysenbach, G. (2004). Improving the quality of web surveys: The checklist for reporting results of Internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 6, e34.

Gebhardt, W. A., Kuyper, L., & Greunsven, G. (2003). Need for intimacy in relationships and motives for sex as determinants of adolescent condom use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 154–164.

Geller, J., Srikameswaran, S., & Zaitsoff, S. L. (2002). The assessment of shape and weight-based self-esteem in adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28, 339–345.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about Internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59, 93–104.

Hall, R. J., Snell, A. F., & Singer-Foust, M. (1999). Item parceling strategies in SEM: Investigating the subtle effects of unmodeled secondary constructs. Organizational Research Methods, 2, 233–256.

Harry, J. (1990). A probability sample of gay males. Journal of Homosexuality, 19, 89–104.

Holland, J., Ramazanoglu, C., Scott, S., Sharpe, S., & Thomson, R. (1992). Pressure, resistance, and empowerment: Young women and the negotiation of safer sex. In P. Aggleton, P. Davies, & G. Hart (Eds.), AIDS: Rights, risk, and reason (pp. 142–162). London: Routledge Farmer.

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Impett, E. A., Gable, S. L., & Peplau, L. A. (2005). Giving up and giving in: The costs and benefits of daily sacrifice in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 327–344.

Impett, E. A., & Peplau, L. A. (2003). Sexual compliance: Gender, motivational, and relationship perspectives. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 87–100.

Josephs, R. A., Markus, H. R., & Tafarodi, R. W. (1992). Gender and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 391–402.

Kernis, M. H. (2003). Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 1–26.

Kiefer, A. K., & Sanchez, D. T. (2007). Scripting sexual passivity: A gender role perspective. Personal Relationships, 14, 269–290.

Klem, L. (2000). Structural equation modeling. In L. G. Grimm & P. R. Yarnold (Eds.), Reading and understanding MORE multivariate statistics (pp. 227–260). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Knee, C. R., Canavello, A., & Bush, A. L. (2008). Relationship-contingent self-esteem and the ups and downs of romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 608–627.

Konik, J., & Stewart, A. (2004). Sexual identity development in the context of compulsory heterosexuality. Journal of Personality, 22, 815–844.

Kurdek, L. A. (2003). The allocation of household labor in homosexual and heterosexual cohabitating couples. Journal of Social Issues, 49, 127–139.

LaGuardia, J. G., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 367–384.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., & Rosen, R. C. (1999). Sexual dysfunction in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. Journal of the American Medical Association, 281, 537–544.

Leigh, B. C. (1989). Reasons for having and avoiding sex: Gender, sexual orientation, and relationship to sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 26, 199–209.

MacKinnon, C. A. (1987). A feminist theory of the state. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., Balla, J. R., & Grayson, D. (1998). Is more ever too much? The number of indicators per factor in confirmatory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 33, 181–220.

Murray, S. L., Bellavia, G., Feeney, B., Homes, J. G., & Rose, P. (2001). The contingencies of interpersonal acceptance: When romantic relationships function as a self-affirmational resource. Motivation and Emotion, 25, 163–189.

O’Sullivan, L. F., & Algeier, E. R. (1998). Feigning sexual desire: Consenting to unwanted sexual activity in heterosexual dating relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 86–109.

Park, L. E., & Crocker, J. (2005). Interpersonal costs of seeking self-esteem. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin, 31, 1587–1598.

Park, L. E., Sanchez, D. T., & Brynildsen, K. (in press). Maladaptive responses to relationship dissolution: The role of relationship contingent self-worth. Journal of Applied Social Psychology.

Raykov, T., Tomer, A., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1991). Reporting structural equation modeling results in psychology and aging: Some proposed guidelines. Psychology and Aging, 6, 499–503.

Rubin, L. (1990). Erotic wars: What happened to the sexual revolution? New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux.

Sanchez, D. T., & Crocker, J. (2005). Investment in gender ideals and well-being: The role of external contingencies of self-worth. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 63–77.

Sanchez, D. T., Crocker, J., & Boike, K. R. (2005). Doing gender in the bedroom: Investing in gender norms and the sexual experience. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1445–1455.

Sanchez, D. T., Good, J., Kwang, T., & Saltzman, E. (2008). When finding a mate becomes urgent: Why relationship contingency predicts men’s and women’s body shame. Social Psychology, 39, 90–102.

Sanchez, D. T., Kiefer, A., & Ybarra, O. (2006). Sexual submissiveness in women: Costs for autonomy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 512–524.

Sanchez, D. T., & Kwang, T. (2007). When the relationship becomes her: Revisiting body concerns from a relationships contingency perspective. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 401–414.

Sell, R. L. (1996). Sampling homosexuals, bisexuals, and lesbians for public health research: A review of literature from 1990–1992. Journal of Homosexuality, 30, 31–47.

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this article, Ms. Moss-Racusin was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and Ms. Phelan was supported by a Jacob Javits Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanchez, D.T., Moss-Racusin, C.A., Phelan, J.E. et al. Relationship Contingency and Sexual Motivation in Women: Implications for Sexual Satisfaction. Arch Sex Behav 40, 99–110 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9593-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9593-4