Abstract

This study examined sexual satisfaction and its social and behavioral correlates among urbanites aged 20–64 in China, using data from a nationally representative sample of 1,194 women and 1,217 men with a spouse or other long-term sexual partner with whom they had sex during the last year. The results from structural equation models suggest a multiplex set of determinants of sexual satisfaction, including relationship characteristics, sexual knowledge and personal values, physical vitality, and environmental impediments. A large proportion of the effect of these background characteristics was mediated by frequent orgasms, varied sexual practices, and perceived partner affection. In particular, much of the effect of knowledge and beliefs was mediated through variety in sexual practices. While many of the observed patterns were shared among women and men, much of the effect of relationship characteristics was mediated through perceived partner affection for women. Men, in contrast, paid greater attention to his partner's physical attractiveness and to her extramarital sex. A sexual transition is well underway in urban China, even if more rapidly for men than for women. While knowledge and values are arguably more important in this transitional period, many antecedents of sexual well-being drawn from the literature on sexual behavior in developed Western countries are also applicable to urban China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Past research suggests multiple linkages between sexual satisfaction, relationship quality, and personal knowledge and values (Cupach & Comstock, 1990; Edwards & Booth, 1994; Farley & Davis, 1980; Greeley, 1991; Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997). Since most research has focused on Western populations, whether these linkages are present in other societies remains unclear. This study examined these linkages in China.

Chinese sexuality was traditionally based on Confucian and Taoist philosophies, which viewed sex for pleasure as detrimental to social order and personal health (Ruan, 1991). Some of these tendencies were intensified when China's post-1949 socialist government strictly regulated sexual behavior (e.g., tight control over prostitution, promotion of monogamous marriage, and restraints on divorce) (Evans, 1997; Hershatter, 1997; Pan, 1993; Ruan, 1991). However, since the early 1980s, increased Western influence via the mass media and a growing market economy changed the social norms and values associated with love, marriage, and sex (Farquhar, 2002; Farrer, 2002; Herold & Byers, 1994; Higgins, Zheng, Liu, & Sun, 2002; Pan, 1993). Women are once again concerned about appearance (Luo, Parish, & Laumann, 2005). Premarital sex, divorce, prostitution, and sexually transmitted infections increased (Cohen, Ping, Fox, & Henderson, 2000; Diamant, 2000; Evans, 1997; Liu, Ng, Zhou, & Haeberle, 1997; Pan, 1993; Parish et al., 2003; Tang & Parish, 2000; Wang, Jiang, Siegal, Falck, & Carlson, 2001). Examining sources of sexual satisfaction in this context will potentially provide a better understanding of both sexual practices and attitudes in contemporary China, and of human sexuality in general.

Previous sexual satisfaction research

Previous sexual satisfaction research using large population-based surveys suggests five general determinants of sexual satisfaction: (1) sexual practices; (2) social-emotional aspects of the relationship with sex partner; (3) knowledge, values, and attitudes about sexual matters; (4) general physical vitality and health; and (5) environmental impediments to sexual satisfaction (e.g., lack of privacy) (Bancroft, Loftus, & Long 2003; Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997; Waite & Joyner, 2001). While previous studies have drawn attention to each of these hypothesized determinants of sexual satisfaction, no study considered all of them at once. Consequently, there is little, if any, information available on the relative importance of each factor, the extent to which factors overlap, or the empirical adequacy of existing models of sexual satisfaction. The research presented here used structural equation modeling (SEM) in an attempt to provide this missing information.

We review prior findings about each of the five general determinants of sexual satisfaction. We provide a conceptual model that integrates these findings, and then use SEM methods to estimate the parameters of this model with data from the China Health and Family Life Survey (CHFLS). Parameter estimates of that model and the general fit of the model to the data provide answers to questions about the effects of the five determinants, the connections between the five determinants, and the adequacy of previous theory as an explanation of sexual satisfaction.

Sexual practices

The link between behavioral aspects of sex life and sexual satisfaction appears in existing research. Variety of sexual techniques, frequency of intercourse, and frequency of orgasm are associated with sexual satisfaction. Achieving orgasm is an important predictor of sexual satisfaction, especially for women (Darling, Davidson, & Cox, 1991). Greeley (1991) reported that experimentation with love play contributed to sexual satisfaction. Similarly, sex therapy often encourages fondling and sexual experimentation (Kaplan, 1974; Masters & Johnson, 1970). In a Chinese study, frequency of intercourse, caressing during sex, and frequency of wife's orgasm increased sexual satisfaction (Zhou, 1993).

Although many studies found that sexual practices were associated with sexual satisfaction, several issues remain unresolved. One is the nature of the link between physical behavior and perceived satisfaction, particularly for women. Research shows that people who reported sexual dysfunctions sometimes did not report lack of sexual satisfaction (Frank, Anderson, & Rubinstein, 1978; Fugl-Meyer & Fugl-Meyer, 1999). And, despite a link between reported orgasm and satisfaction, scholars remain puzzled that this link is not closer (Darling et al., 1991; Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997; Lief, 2001; Whipple, 2001; Zhou, 1993). An additional concern is to sort out the relative role of proximate, endogenous (e.g., orgasm), and distal (e.g., values, beliefs) antecedents of satisfaction (Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997).

Social-emotional relationship with sex partner

Relationship issues have been considered by many practitioners to be at the heart of sexual problems (Kaplan, 1974; Masters & Johnson, 1970; Southern, 1999; Young, Denny, Young, & Luquis, 2000). Much of this research focused on male-female differences in the relative importance of various relationship characteristics (Dunn, Croft, & Hackett, 1999). Evolutionary approaches suggest that men seek youth, beauty, and sexual exclusivity in order to increase the certainty of genetic propagation. To ensure their offspring's survival, women seek men with resources and expect a stable, long-term relationship (Buss, 1998; Townsend & Wasserman, 1997). Social constructionists argue that satisfaction is shaped less by a woman's pursuit of resources than by male misuse of power (e.g., hitting), by his failing to help with chores, and his failing to understand her sexual needs (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983; DeMaris, 1997; Hirschman & Larson, 1998; Hochschild, 1989; MacMillan & Gartner, 1999; Rogers & DeBoer, 2001; Schwartz, 2000; Schwartz & Rutter, 1998). Waite and Joyner (2001) suggested that commitment has a positive role for both men and women.

Sexual knowledge, values, and attitudes

A diverse literature implies that sexual interest and desire are greatly conditioned by knowledge and values, particularly for women. Laboratory experiments found that women's perceptions of their own sexual arousal were imperfectly correlated with their instrumentally-measured vaginal lubrication—a physiological indicator of female sexual arousal; this finding suggests a strong interpretive filter of sexual response (Everaerd, Laan, Both, & van der Velde, 2000; Laan, Beekman, & Everaerd, 2001). Some studies suggest that cultural norms and values exert greater influence on women's interpretations of their sexual responses than on men's interpretations of their own sexual response (Baumeister, 2000; Baumeister & Tice, 2001). Other values, including religious values, were reported to condition sexual expression and satisfaction (Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997; Waite & Joyner, 2001; Young et al., 2000). In other studies, pleasure seeking (“sexual assertiveness”) and sexual knowledge were reported to condition both men's and women's sexual satisfaction (Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997; Hurlbert, 1991). Sexual knowledge gained from literature or pictures was reported to have both positive and negative effects on sexual satisfaction. Viewing sexual materials can be positive for sex therapy (Duncan & Donnelly, 1991; Duncann & Nicholsson, 1991; Trostle, 1993) or it can produce negative consequences, such as aggressive sexual behavior and sexual coercion (Janghorbani & Lam, 2003; Malamuth, Addison, & Koss, 2000; Malamuth & McIlwraith, 1988). Given that in China most of these materials are contraband imports that are freely and cheaply available on the street, the “negative consequences” argument could well apply. Or, it could be, if the typical assumption in the therapy literature is correct, and there are few other sources of instruction, greater knowledge, regardless of how acquired, could produce higher levels of satisfaction.

General physical health and vitality

Previous studies reported that physical health and vitality affect sexual satisfaction. Self-rated health, diabetes, high blood pressure, blood pressure medication, depression, heavy smoking, and alcohol consumption have been considered (Everaerd et al., 2000; Everaerd, Laan, & Spiering, 2000; Feldman, Goldstein, Hatzichristou, Krane, & McKinlay, 1994). Some studies treated health and vitality as mere control variables, while others have paid particular attention to the effects of age and health for men, and have compared these effects to the impact of relationship quality for women (Dunn et al., 1999; Dunn, Croft, & Hackett, 2000; Trudel, Turgeon, & Piché, 2000).

Impediments to sexual satisfaction

Lack of privacy and social pressure to avoid pregnancy can impede sexual satisfaction. By Western standards, Chinese tend to live in small apartments crowded with young children, parents and even grandparents (Liu et al., 1997; Pimentel, 2000). Without appropriate controls for crowding and fear of pregnancy, the effects of these factors on sexual satisfaction could be confounded with Chinese-Western differences in values, attitudes, sexual knowledge, or other factors.

Conceptual model

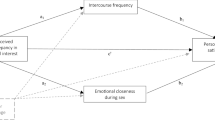

Figure 1 presents a conceptual and empirical model of sexual satisfaction. This model integrates patterns from previous research and establishes a basis for our empirical analysis. In this model, theoretical constructs are shown in bold face type. If constructs are not directly measured, observed indicators of these constructs are shown in plain font. All observed variables are described in detail in the following section.

The dependent variable of ultimate interest in this model is the construct, Sexual Satisfaction. In the empirical analysis, Sexual Satisfaction is a latent variable that we measured with five observed indicators (physical satisfaction, emotional satisfaction, not ashamed, thrilled, and believe sex not dirty). The conceptual model allows, but does not require, sexual satisfaction to be influenced by characteristics of the relationship between participant and partner (eight variables), sexual knowledge and values (seven variables), vitality (three variables), impediments to sexual satisfaction (two variables), variety of sexual practices (a latent variable with nine indicators), frequency of orgasm, and perceived affection provided by the participant's partner. Following a suggestion that marital well-being and sexual feelings influence each other (Byers, 2005; Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Edwards & Booth, 1994), the model permits but does not require reciprocal effects between sexual satisfaction and perceived partner affection. The model permits a variety of indirect, as well as direct, effects on sexual satisfaction. For example, the model permits sexual knowledge and values to affect sexual satisfaction directly, and/or indirectly through its effects on variety of sexual practices, frequency of orgasm, and perceived partner affection.

Following previous research, we hypothesized gender differences in the production of sexual satisfaction. Thus, we proposed the same conceptual model for men and women, but we expected to find substantial gender differences in parameters of this model. Because traditional Chinese culture values men's sexual pleasure much more than that of women (Evans, 1997; Gilmartin, 1994; Pan, 1993; Renaud, Byers, & Pan, 1997; Zhou, 1993), these gender differences could be particularly strong in China.

Method

Participants

Our analysis was based on data from the China Health and Family Life Survey, carried out between August 1999 and August 2000. The CHFLS utilized a sample of the adult population of China aged 20–64, who did not reside in Tibet or Hong Kong. The sample design included 14 strata, 48 primary sampling units, 60 neighborhoods, and 5,000 individuals aged 20–64. Geographic areas with high rates of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) were oversampled. 3,821 participants completed the interview, providing a final response rate of 76%.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire to Chinese was performed by a forward translation from English to Chinese followed by an independent backward translation from Chinese into English. Interviews were conducted in neighborhood facilities away from the participant's home. Oral and computer-entered consent was obtained prior to the hour-long interview, which began with the interviewer in control of the computerized interview and continued with the laptop computer controlled entirely by the participant. The methods were approved by institutional review boards at the University of Chicago and Renmin University in Beijing. Details about sample design and the final questionnaire used in this study are available at http://www.src.uchicago.edu/prc/chfls.php and in Parish et al. (2003). Because nearly 80% of the participants in the survey were urban residents, we limited the sample for this particular analysis to 3,055 urban participants, for whom we had a larger sample size and more robust estimates. The urban participants were further limited to 2,672 people currently in a stable relationship and, of those, to the 2,478 people currently having sexual intercourse. The people in stable relationships were 96% married, 2% cohabiting, and 2% other. The “other” relationships included people who have had sex together for at least six months. For the 18 people who currently had two or more sexual relationships, we asked for the most intimate of those relationships. Further limiting the cases to those with data on our key analytical variables, the final sample included 2,411 people (1,194 women and 1,217 men).

Measures

The variables used in the analysis are described in this section. The response categories and distributions of these variables are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Endogenous variables

Sexual satisfaction

Participants were asked if sex with their current partner made them feel: (1) physically satisfied, (2) emotionally satisfied, (3) ashamed, (4) thrilled, and (5) whether they felt the sex was dirty.

Frequency of orgasm

Participants were given a definition of orgasm and then asked, “When having sex with your current partner, how often did you have an orgasm?” The definition of female orgasm stated: “Female orgasm can be observed when there is: (1) uncontrolled vaginal contractions or muscle contractions of other parts of the body; or (2) strong feelings of pleasure and excitement.” The definition of male orgasm stated: “Usually, a male reaches orgasm when he ejaculates, and at the same time feels extremely excited (ejaculation is when sperm shoots or flows out).” In total, 56% of sexually active, partnered, urban men and 30% of similar women said they knew the definition before we gave it.

Variety of sexual practices

Participants reported on nine activities in the past year: kissing, caressing female partner's breast, genital contact (each way), oral sex (each way), anal sex, whether the female partner was on top, and whether “from behind (‘doggy,’ or in Chinese, ‘piggy’) style” was used.

Perceived partner affection

Perceived partner affection was measured with the question: “Is your partner sufficiently considerate and affectionate to you in daily life?”

Exogenous variables

Relationship characteristics

We examined several aspects of the marital/partner relationship (Table 2). From the question “Does your partner spend more time on chores than you do?” we derived an indicator of whether the man in the relationship did at least half the chores. We compared continuously married participants with those who were cohabiting, single, divorced, widowed or remarried. Couples were coded as having experienced domestic violence in their relationship if the participant answered “yes” to either of the questions: (1) “For whatever reason, has your partner ever hit you?” and (2) “For whatever reason, have you ever hit your partner?”

Participants also reported on several partner characteristics that might influence the relationship. We compared participants whose partner often or always had an orgasm with those whose partner never, rarely or only sometimes had orgasm during sex last year. Partner's extramarital sex was based on participants’ answer to the question: “Throughout the sexual relationship with your current partner, has your partner ever had sex with other people (even if it happened just once)?” The response was coded 1 (yes, definitely/perhaps, but I don't know for sure) and 0 (definitely not). Participants whose partner was away from home for more than one week in the past year were compared with those whose partner rarely or never left home. The partner's sexual attractiveness was coded 1 (very much/somewhat) or 0 (not much/not at all) based on response to the question: “Compared with people of the same age, how attractive is your partner in the eyes of the opposite sex?” We used the same coding for the participant's assessment of his/her own attractiveness.

Knowledge and values

We considered participants as having a gender egalitarian sex view if they answered “Women should also be proactive” to the question: “Some say that in sex, men should be proactive and take the lead while women should be cooperative and acquiescent. What is your opinion?” We created a permissive sex values scale from four items: (1) “Some say that one can have sex just for pleasure with someone whom he or she is not in love with. Do you agree?” (2) “Some say that it is ok to have sex with someone other than your spouse after marriage. Do you agree?” (3) “Nowadays in our society, some married people have sex with those other than their spouse. Do you think that each such case should be treated individually or that these people should all be punished?” And (4) “Nowadays in our society, some couples have sex when they are dating, and they eventually get married. Is this a moral issue?” The scale was the average of standardized responses to the four items with a scale reliability coefficient of .61. Adjusted to range from 1 to 4, higher values on this scale indicated more permissive sex values.

There were five knowledge items: (1) a claim by the participant of prior knowledge of the definition of orgasm given just before this question; (2) ability to pick the clitoris when asked to identify the most sexually sensitive part of a woman's body, first picking the general region of a body in one question and then in the next question picking the numbered arrow pointing to the clitoris in a picture of female genitalia; (3) whether the participant viewed erotic video(s) or other sexual materials last year; (4) the participant's own years of education; and (5) partner's years of education.

Physical vitality

We used three indicators of physical vitality. Own age was in years. Age gap was the man's age minus the woman's age, with extreme values truncated to a range of −4 to 11 years. We compared participants who reported thinking about things sexual in daily life at least once to several times a week with those reporting thinking of sex several times a month or less.

Impediments

Our first indictor of environmental impediments to sex was the response that at least once last year the participant did not want to have sex because of fear of becoming pregnant. Our second indicator of environmental impediments was the reply “a lot/somewhat” (coded 1) versus “no interference” (coded 0), in response to the question, “How seriously do your living conditions affect your sex life?”

Statistical methods

We began our analysis with description of variables used in this paper. Standard errors and significance tests for descriptive statistics used Huber-White “sandwich” estimation to make proper account of sample stratification, unequal sampling probabilities, and clustering. After data description, we turned to SEM of the model shown in Fig. 1. With separate analyses for men and women participants, the SEM estimation reported here was accomplished with the computer program Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2004). Mplus accommodates continuous, dichotomous, and ordinal variables. Except for the continuous variables of education, age, relative age, and permissive sexual values scale, all the original variables were dichotomous or ordinal. Estimation was accomplished with weighted least squares with robust standard errors (MLSMV), providing adjustment for sample stratification, clustering and unequal selection probability.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the observed indicators of latent factors. For each of the five indicators of sexual satisfaction, men were 8–24% more likely than women to be in the extreme categories of satisfaction and these were all at statistically significant levels. Also, men reported having orgasm more often. Men and women reported similar levels of several sexual activities (woman on top, from behind, oral sex, and anal sex). However, for some activities, men reported statistically higher levels than women (kiss, caress woman's breast, caress woman's genitals, and caress man's genitals). More generally, about 50–60% of women and men reported “woman on top” and “from behind” positions. About 27% practiced oral sex and less than 4% tried anal sex. More women than men complained that the care they received from their partner in daily life was insufficient—41% for women and only 24% for men.

Men and women differed on several of the background characteristics that served as exogenous variables in our analysis (Table 2). The gender differences were more muted for relationship characteristics. Men and women agreed on the man's role in chores, on spousal hitting, and on ratings of their own and their partner's attractiveness, with the partner's attractiveness being rated higher than one's own attractiveness. Men were more likely to have not been continuously married (they were more likely to have remarried or to be in cohabiting relationships), to be thought of as having an orgasm, to be suspected of having an extramarital affair (which in a separate analysis the men agreed with), and to be away more often.

Men and women differed more consistently on sexual knowledge and value items. Women were less likely than men to believe that women and men should be equal in sex (65% vs. 80%) or to identify the clitoris (39% vs. 56%), all of which could be consistent with a more rapid spread of new sexual values and pornography among men (Table 2). Women were less likely than men to know the definition of orgasm (30% vs. 56%), to consume sexual materials (23% vs. 42%), or to hold permissive sex values (1.89 vs. 2.34). Women were less likely to think of sex often and, conversely, more likely to fear pregnancy during sex. About 33% of men and women complained that their living conditions (children, grandparents sharing a small space, etc.) hindered their sexual activities.

SEM measurement results

Table 3 presents results for the measurement component of the SEM models. For both women and men, physical satisfaction and emotional satisfaction had the largest coefficients from sexual satisfaction, followed by feeling thrilled. Feeling ashamed and feeling dirty had smaller loadings on satisfaction. Because the positively and negatively worded questions may represent different theoretical constructs, we also ran the SEM models with only physical satisfaction, emotional satisfaction, and feeling thrilled as indicators of sexual satisfaction, with the finding that the relationships of satisfaction with other variables in the three-indicator models were similar to those in the five-indicator models. Here, we only present results from the five-indicator model. Not feeling ashamed ranked lower than not feeling dirty for women in their importance for sexual satisfaction while it ranked higher than not feeling dirty for men. This may be the result of strong interview design effect, where participants adapt poorly to items that were reversed in direction (Sudman & Bradburn, 1974).

For variety of sexual practices, oral sex (from either partner), caressing genitals (of either partner), and caressing female partner's breast had higher loadings. Although the unstandardized loadings of caressing woman's genitals and “from behind style” were significantly higher on men than on women, these gender differences were due to gender differences in the variations of these items—the standardized loadings of these items were not significantly different for men and women. Also, although the standardized loading for anal sex was significantly higher for women than for men, it was a trivial difference, given the rarity of this practice in China.

SEM structural results

Tables 4 and 5 present results for the structural component of the SEM models described in Fig. 1. Table 4 displays the total effects (including indirect effects) of exogenous variables on each endogenous variable, while Table 5 reports structural equation coefficients (direct effects net of indirect effects). The Appendix reports the size and significance of the total indirect effects of exogenous variables on each endogenous variable that are equal to the total effects minus the direct effects. In these models, while endogenous and continuous exogenous variables were standardized, dichotomous exogenous variables were unstandardized.

Proximate (endogenous) mechanisms

Results confirmed our expectation of strong influences of orgasm, variety of sexual practices, and perceived partner affection on sexual satisfaction, particularly for women (Table 5). More frequent orgasm and more diverse sexual activities were associated with higher levels of satisfaction for both women and men. As expected, frequency of orgasm had a significantly higher effect on women than on men (.51 vs. .25) and perceived partner affection outside of sex was only significantly associated with women's satisfaction, not with men's. Also as anticipated, sexual satisfaction had a strong feedback effect on perceived partner affection, and this feedback was not significantly different between women and men (final two columns of Table 5). In addition, variety of practices had an indirect effect on satisfaction through its positive effect on frequency of orgasm, resulting in a total effect of variety of practices on satisfaction of .38 (.20+.34×.51) for women and .32 (.25+.27×.25) for men.

Relationship characteristics

The total effects of most relationship variables on sexual satisfaction were significant and substantial (Table 4). The effects of male partner's share of chores, being continuously married, and spousal hitting for women and the effects of spousal hitting and partner's extramarital sex for men were mostly direct (Table 5). The effects of partner's orgasm, extramarital sex and attractiveness and participant's own attractiveness for women were mainly indirect through frequency of orgasms, variety of sexual practices and perceived partner affection. For men, both the direct and indirect effects of partner's orgasm and attractiveness on satisfaction were significant. Many of the indirect effects for women were through perceived partner affection, for which many of the relationship characteristics were important. Although several relationship variables were also significantly associated with men's perceived affection from their partner, their indirect effects on satisfaction through perceived partner affection were not significant because the direct effect of perceived partner affection on men's satisfaction was weak and statistically insignificant.

Knowledge and values

Many of the effects of knowledge and values were not direct but indirect through proximate mechanisms, particularly through the variety of sexual practices. Out of the seven knowledge and value items, five for women and six for men were associated with variety of sexual practices at the p < .05 level and the remaining two were marginally significant for women. However, while education and permissive sex values increased the variety of sexual practices (and, thus, indirectly increased sexual satisfaction), the direct effect of education and permissive sex values was to diminish reported satisfaction, perceived partner affection, and (for women) orgasm. This direct negative effect was so strong that the total effects of education and permissive sex values were all negative and mostly significant (first two columns in Table 4). Another unexpected result was that a distancing from the traditional view that men should lead in sex had opposing effects for men and women, increasing variety of practices for women while decreasing practices for men.

Physical vitality

Physical vitality had their most straightforward effect on satisfaction through age. About 60–67% of the effect of age was direct. The indirect effect of age was mainly caused by the negative effect of age on variety of practices. The total effect of frequent thoughts of sex was also significant for women, though it was mainly indirect. With more frequent thoughts of sex, women and, to a lesser extent, men reported more varied sexual practices and more orgasms. The effect of age gap had more complex patterns. When married with much younger women, men had more varied sexual practices. These same men, however, also reported less care from their wife and fewer orgasms.

Impediments

Fear of pregnancy had a large direct effect on sexual satisfaction. The total effect of living conditions that hindered sex was also significant for women, but it was mainly indirect. Living conditions that hindered sex diminished not only orgasms but also perceived partner affection, particularly for women.

Gender differences

One of our beginning questions concerned gender differences. Those differences were highlighted in Tables 4 and 5, with bold italic numbers indicating that the coefficients for men and women differed at the p < .05 level. Though not all the significant differences were interpretable, several stood out.

Relationship characteristics. Though both women's and men's satisfaction were shaped by relationship characteristics, women and men differed on which aspects were most important. For women, it was perceived partner affection and male share of chores that were most important, while for men, the most important factors were whether their partner was physically attractive, often had orgasms, and avoided extramarital sex (Table 4). The diminished significance of partner's attractiveness, orgasm, and extramarital sex for women weakened the role of “relationship characteristics” in directly shaping women's sexual satisfaction (Table 5). There were three final, somewhat curious patterns: First, most clearly in the direct effects, while men's sexual satisfaction was improved by their partner's physical attractiveness, women's orgasm and variety of practices were improved by women's perception of their own attractiveness. Second, while their partner's greater share of chores improved women's satisfaction and perceived partner affection, men who had this share of chores perceived less affection from their partner. Third, female partner's orgasm increased men's perception of partner affection, but male partner's orgasm had a negative direct effect for women's perception of partner affection.

Knowledge and values. Education and permissive sex values increased the variety of sexual practices for both women and men. However, that increase was greater for men's education and values, which could lead to speculation about who continued to initiate many practices.

Physical vitality. Women were at least as much influenced by age as men, particular in the total effects. Men were more influenced by large age gaps (being married to a younger partner).

Comparison of subsets of characteristics

Figure 2 used the results in Tables 4 and 5 to show linear combinations of the coefficients of sexual satisfaction within a subset of variables. The variables measuring physical vitality and impediments were combined into one subset so that we had balanced numbers of variables in each subset. The joint coefficients were derived by adding the coefficients (or subtracting if the coefficient was negative) of all dichotomous variables and 2 times the standardized coefficients (or −2 times if the coefficient was negative) of all continuous variables within a subset. For example, the joint coefficient of the total effects of all variables measuring knowledge and values for women in Table 4 was 1.29 and the linear constraint L was [1, −2, 1, 1, 1, −2, 2]. Standard errors were calculated using the formula: \(\sqrt {LVL^{\prime} }\), where V is the estimated variance-covariance matrix of the coefficients (Greene, 1993). The variance-covariance matrix of the coefficients for the total effects was estimated from a model where each endogenous variable was regressed on all exogenous variables, but the pathways among endogenous variables were omitted. The coefficients and standard errors from this model were equal to the total effects in the model described in Fig. 1.

Linear Combinations of Coefficients in Subsets of Variables on Sexual Satisfaction. Note. Joint coefficients for sexual satisfaction (and 95% confidence intervals) in SD units. Joint coefficients derived by adding the absolute values of the coefficients of all dichotomous variables and 2 times the absolute values of the coefficients of all continuous variables within a subset. *indicates significant gender difference at p < .05.

The joint effects of all background characteristics were substantial when both their direct and indirect effects were taken into account (Fig. 2, Panel A). For women, any set of background characteristics created an approximately 1.29–1.60 SD units improvement in sexual satisfaction. Men's patterns were in a statistically similar range.

The patterns for direct effects were somewhat more muted (Fig. 2, Panel B). For example, among women, the direct effects were about half those of the total effects (compare the top and bottom panels of Fig. 2). This reduction in effects suggests that to an extent many of the effects of background conditions flowed through the proximate mechanisms (orgasm frequency, sexual practice variety, and partner affection). The combined influence of the proximate mechanisms was statistically larger for women than for men.

SEM model fit

For women, the model fit statistics had a Chi-Square of 31.20 (df=6, p < .001), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of .85, and Root Mean Square Error Approximation of .06. For men, the corresponding statistics were 29.33 (df=6, p < .001), .85, and .06. Statistical significance of the Chi-Square statistic is not informative, as it is proportional to the sample size, other things equal. However, the CFI adjusts for sample size and indicates that there is room for adjustment of the model to fit the data. Performing that adjustment is beyond the scope of this paper—it is our purpose here to specify a model that integrates and reflects the arguments, hypotheses and findings of previous researchers, and to assess that model by application to the CHFLS data. A CFI of .85 is high enough to support the previous research that is the basis of our analysis. It remains for subsequent analysis to determine if a closer fitting model can be obtained by adjusting only the measurement sections of the model, or if more theoretically relevant constructs and pathways need to be added.

Discussion

This study examined sexual satisfaction and its social and behavioral correlates among urban adults in China. The findings contribute to our understanding of the levels and avenues by which sexual satisfaction is achieved in a society in the middle of a sexual transition (Farrer, 2002; Pan, 1993). The contributions include new information on overall satisfaction, gender differences, and the multiple determinants of satisfaction.

The results suggest that, as much as in the rest of the world, most Chinese urbanites are satisfied with their sex life. Moreover, contra the suspicion that many Chinese remain inhibited by traditional beliefs (cf. Ruan, 1991), only 14% of urbanites reported that they were ever ashamed of sex and only 27% reported that they ever felt that sex with their spouse or other primary partner was dirty. These percentages were higher than in the 1992 national study of sexual behavior in the U.S. (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994), where no more than 5% reported that sex with their spouse or other main partner made them feel sad or guilty (calculated from raw data). Nevertheless, the Chinese percentages still seem modest compared to accounts of how traditional values have not receded. The modest percentages (much lower among younger participants) seem more consistent with the argument that younger Chinese have begun to embrace new ideas in sexual practices and to try out diverse sexual activities in order to achieve satisfaction (Evans, 1997; Farrer, 2002; Pan, 1993).

It has been suggested that, on top of enduring gender differences, the embrace of new sexual ideas occurs more rapidly for men than for women (Higgins et al., 2002; Liu et al., 1997). Regardless of the exact origin of these tendencies, strong gender differences remain. Men exceeded women in not being ashamed about sex, not feeling that sex was dirty, rejecting the traditional notion that men should be the ones who initiate sex, and being able to identify the clitoris in a picture (Tables 1 and 2). Educated men with more permissive sex values seemed to lead in the adoption of new sexual practices (Table 4). Consistent with studies in the U.S. and Finland (Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997; Laumann et al., 1994), but contrary to studies in England, Denmark, Sweden, and Canada (Dunn et al., 2000; Fugl-Meyer & Fugl-Meyer, 1999; Renaud et al., 1997; Ventegodt, 1998), Chinese women were less satisfied than men with their sex life. The reports of lower levels of satisfaction could represent not only more traditional values but also insufficiently transformed male behavior. Women were more likely than men to report that their partner provided insufficient affection, never kissed during sex, and had extramarital sex (Tables 1 and 2). Increased consciousness about what they deserve out of sex may arguably have caused some women to report not more perceived partner affection and sexual satisfaction but just the opposite. This interpretation is consistent with the finding that education and permissive sexual values reduced satisfaction (Table 5). Moreover, particularly for women, greater education reduced reports of perceived partner affection and more permissive sex values reduced reported orgasms (Table 4). So, the circumstantial evidence from the survey suggested a rapid sexual revolution, accompanied perhaps by lagging experiences for women and some men, a situation perhaps not completely dissimilar from what Rubin (1990, 1992) reported two decades after the sexual revolution in the U.S.

One issue in the analysis was the relative role of relationship quality and of knowledge and values compared to other parameters, such as age. An existing literature suggested that, particularly for women, values and knowledge and couple relationships play at least as an important role as physical conditions in determining dysfunctions and sexual rewards (Bancroft, 2002; Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Kaplan, 1974; Masters & Johnson, 1970; Southern, 1999; Tiefer, 2000; Young et al., 2000). Our results were consistent with this emphasis on multiple determinants of sexual satisfaction. Statistically, each of three subsets of variables (relationship characteristics, knowledge and values, and physical vitality and impediments) had consequences of about equal magnitude (Fig. 2). The more general conclusion that emerges is that, for both men and women, multiple conditions help determine whether people find satisfaction in sex.

The findings on relationship quality require special comment. Not surprisingly, more affection provided by the partner produced a more satisfied sex life for women and, conversely, a more satisfied sex life increased perceptions of partner affection for both women and men. As might be expected for women, many consequences of relationship quality for sexual satisfaction flowed through perceived partner affection (Tables 4 and 5). At first glance, the finding that “relationship quality” mattered greatly for men seems surprising. That, however, is in many ways deceiving, for the focus of the men in our “relationship quality” was less on sharing of chores, absence of hitting, and affection and more on whether his female partner was physically attractive, having orgasm, or suspected of an extramarital affair. In ways that evolutionary approaches would find compelling, men put more emphasis on their partner's appearance, availability for sexual monitoring (their partner was not away for more than a week), and extramarital affair (Buss, 1998; Townsend & Wasserman, 1997).

An applied therapy literature has emphasized changes in knowledge and values and improvements in sexual techniques and practices as avenues to increased sexual satisfaction (e.g., Christopher & Sprecher, 2000; Everaerd et al., 2000; Everaerd, Laan, & Spiering, 2000; Haavio-Mannila & Kontula, 1997; Kaplan, 1974; Masters & Johnson, 1970; Young et al., 2000). Consistent with that literature, the Chinese data suggest not only that knowledge and values are important but that the intervening (proximate) mechanism through which knowledge and values improve sexual satisfaction is through increased sexual practices, starting with kissing and fondling and continuing through oral sex and other sexual techniques (Tables 4 and 5). Arguably, one might infer that this type of increased knowledge is particularly important in transitional societies such as China, where the sexual revolution is just beginning. The one wrinkle in this pattern is the one already noted, which is that increased education and more permissive sex values may not only increase the variety of sexual practices but also raise expectations in ways that make one more critical of current sexual practices (Tables 4 and 5). Raised consciousness and expectations may also explain the finding that sexual material use increased variety, even while its direct effect on sexual satisfaction was not significant. Another finding was that for women orgasm was even more strongly associated with satisfaction than for men, consistent with previous research (Darling et al., 1991). Given these patterns, it appears that encouraging women to experiment with diverse sexual activities is one key to helping them to achieve orgasm, and ultimately, a more satisfying sex life.

One pattern in the West was that those who were married had higher levels of sexual satisfaction than those who were not married, at least emotionally (Laumann et al., 1994; Waite & Joyner, 2001). This finding was not repeated in the Chinese data. Continuously married, urban Chinese women and men were no more satisfied than anyone else. Indeed, continuously married women were significantly less satisfied, even after the negative effect of being continuously married on sexual activities and the positive effect of being continuously married on perceived partner affection were taken into account (Table 5). In additional analyses that combined the continuously married with those who were remarried, as was done in Waite and Joyner (2001), we found that the direct effect of being married on satisfaction was no longer significant, though it remained in a negative direction (details not shown). This finding is consistent with an argument that marriage among urban Chinese may be problematic because, in at least some of these marriages, duty rather than romantic love is the glue that makes couples stay together (Xu & Ye, 1999).

Our study had several limitations. First, our analysis was only for urban residents. Since China's urban residents have more education and resources than rural residents (Farrer, 2002), the findings from this study should not be taken as representative of China as a whole. Second, as in all studies based on cross-sectional data, we could not rule out strong feedback effects (e.g., less partner affection could be as much the cause as the result of extramarital affairs). The structural equation models attempted to deal with this type of issue, but only for a limited subset of proximate mechanisms. Moreover, as in all research that used only people who were currently sexually active, our results could suffer from selection bias, i.e., the people who were most dissatisfied with their sexual relationship might have simply quit having sex and therefore no longer have been available for analysis.

In summary, with a large, nationally representative urban sample, this study provides one of the first studies of the determinants of sexual satisfaction in a large developing country in the midst of a major sexual transformation. The results suggest that the determinants of sexual satisfaction are multiplex, for both women and men. Knowledge and values increase the variety of sexual practices, producing higher levels of satisfaction even while some people become more sensitive to the inadequacies of their current sexual experience. For women, relationship characteristics have a major effect on perceived partner affection, which in turn shapes sexual satisfaction. While knowledge and values may be even more important in urban China during this period of rapid sexual transition, we see more similarities rather than dissimilarities with the literatures from developed countries.

References

Bancroft, J. (2002). The medicalization of female sexual dysfunction: The need for caution. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 451–455.

Bancroft, J., Loftus, J., & Long, J. S. (2003). Distress about sex: A national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 193–208.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 347–374.

Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (2001). The social dimension of sex. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Blumstein, P., & Schwartz, P. (1983). American couples. New York: Pocket Books.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley

Buss, D. M. (1998). Sexual strategies theory: Historical origins and current status. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 19–31.

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 113–118 .

Christopher, F. S., & Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 999–1017.

Cohen, M. S., Ping, G., Fox, K., & Henderson, G. (2000). Sexually transmitted diseases in the People's Republic of China in Y2K. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 27, 143–145.

Cupach, W. R., & Comstock, J. (1990). Satisfaction with sexual communication in marriage: Links to sexual satisfaction and dyadic adjustment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 179–186.

Darling, C. A., Davidson, J. K., & Cox, R. P. (1991). Female sexual response and the timing of partner orgasm. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 17, 3–21.

DeMaris, A. (1997). Elevated sexual activity in violent marriages: Hypersexuality or sexual extortion? Journal of Sex Research, 34, 361–373.

Diamant, N. (2000). Revolutionizing the family: Politics, love, and divorce in urban and rural China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Duncan, D. F., & Donnelly, J. W. (1991). Pornography as a source of sex information for students at a private northeastern university. Psychological Reports, 68, 782.

Duncan, D. F., & Nicholsson, T. (1991). Pornography as a source of sex information for students at a southeastern state university. Psychological Reports, 68, 802.

Dunn, K. M., Croft, P. R., & Hackett, G. I. (1999). Association of sexual problems with social, psychological, and physical problems in men and women: A cross sectional population survey. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 53, 144–148.

Dunn, K. M., Croft, P. R., & Hackett, G. I. (2000). Satisfaction in the sex life of a general population sample. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 141–151.

Edwards, J. N., & Booth, A. (1994). Sexuality, marriage, and well-being: The middle years. In A. S. Rossi (Ed.), Sexuality across the life course (pp. 233–259). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Evans, H. (1997). Women and sexuality in China: Female sexuality and gender since 1949. New York: Continuum Publishing.

Everaerd, W., Laan, E., Both, S., & Van Der Velde, J. (2000). Female sexuality. In L. T. Szuchman & F. Muscarella (Eds.), Psycho- logical perspectives on human sexuality (pp. 101–147). New York: John Wiley.

Everaerd, W., Laan, E., & Spiering, M. (2000). Male sexuality. In L. T. Szuchman & F. Muscarella (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on human sexuality (pp. 60–101). New York: John Wiley.

Farley, F. H., & Davis, S. A. (1980). Personality and sexual satisfaction in marriage. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 6, 56–62.

Farquhar, J. (2002) Appetites: Food and sex in postsocialist China. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Farrer, J. (2002). Opening up: Sex and market in Shanghai. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Feldman, H. A., Goldstein, I., Hatzichristou, D. G., Krane, R. J., & McKinlay, J. B. (1994). Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: Results of the Massachusetts male aging study. Journal of Urology, 151, 54–61.

Frank, E., Anderson, C., & Rubinstein, D. (1978). Frequency of sexual dysfunction in “normal” couples. New England Journal of Medicine, 299, 111–115.

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. (1999). Sexual disabilities, problems and satisfaction in 18–74 year old Swedes. Scandinavian Journal of Sexology, 2, 79–105.

Gilmartin, C. K. (1994). Engendering China: Women, culture, and the state. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Greeley, A. M. (1991). Faithful attraction: Discovering intimacy, love, and fidelity in American marriage. New York: Doherty.

Greene, W. H. (1993). Econometric analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan.

Haavio-Mannila, E., & Kontula, S. (1997). Correlates of increased sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 399–419.

Herold, E. S., & Byers, E. S. (1994). Sexology in China. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 3, 263–269.

Hershatter, G. (1997). Dangerous pleasures: Prostitution and modernity in twentieth-century Shanghai. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Higgins, L. T., Zheng, M., Liu, Y., & Sun, C. H. (2002). Attitudes to marriage and sexual behaviors: A survey of gender and culture differences in China and United Kingdom. Sex Roles, 46, 75–89.

Hirschman, L. R., & Larson, J. E. (1998). Hard bargains: The politics of sex. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift. New York: Avon Books.

Hurlbert, D. F. (1991). The role of assertiveness in female sexuality: A comparative study between sexually assertive and sexually nonassertive women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 17, 183–190.

Janghorbani, M., & Lam, T. H. (2003). Sexual media use by young adults in Hong Kong: Prevalence and associated factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 545–553.

Kaplan, H. S. (1974). The new sex therapy: Active treatment of sexual dysfunctions. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Laan, E., Beekman, L., & Everaerd, W. (2001). Response to sexology and the pharmaceutical industry: The threat of co-optation. Journal of Sex Research, 38, 179–180.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lief, H. I. (2001). Satisfaction and distress: Disjunctions in the components of sexual response. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 27, 169–170.

Liu, D., Ng, M., Zhou, L., & Haeberle, E. J. (1997). Sexual behavior in modern China: Report on the nationwide survey of 20,000 men and women. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company.

Luo, Y., Parish, W. L., & Laumann, E. O. (2005). A population-based study of body image concerns among urban Chinese adults. Body Image, 2, 333–345.

MacMillan, R., & Gartner, R. (1999). When she brings home the bacon: Labor-force participation and the risk of spousal violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 947–958.

Malamuth, N. M., Addison, T., & Koss, M. (2000). Pornography and sexual aggression: Are there reliable effects and can we understand them? Annual Review of Sex Research, 11, 26–91.

Malamuth, N. M., & McIlwraith, B. (1988). Fantasies and exposure to sexually explicit magazines. Communication Research, 15, 753–771.

Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1970). Human sexual inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2004). Mplus user's guide (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Pan, S. (1993). A sex revolution in current China. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 6, 1–14.

Parish, L. W., Laumann, E. O., Cohen, M. S., Pan, S., Zheng, H., Hoffman, I., et al. (2003) Population-based study of chlamydial infection in China: A hidden epidemic. Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 1265–1273.

Pimentel, E. E. (2000). Just how do I love thee? Marital relations in urban China. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 32–47.

Renaud, C., Byers, E. S., & Pan, S. (1997). Sexual and relationship satisfaction in mainland China. Journal of Sex Research, 34, 399–415.

Rogers, S., & DeBoer, D. D. (2001). Changes in wives' income: Effects on marital happiness, psychological well-being, and the risk of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 458–472.

Ruan, F. F. (1991). Sex in China. New York: Plenum.

Rubin, L. B. (1990). Erotic wars: What happened to the sexual revolution? New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Rubin, L. B. (1992). Worlds of pain: Life in the working class family. New York: Basic Books.

Schwartz, P. (2000). Creating sexual pleasure and sexual justice in the twenty-first century. Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews, 291, 213–219.

Schwartz, P., & Rutter, V. (1998). The gender of sexuality. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

Southern, S. (1999). Facilitating sexual health: Intimacy enhancement techniques for sexual dysfunction. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 21, 15–32.

Sudman, S., & Bradburn, N. M. (1974). Response effects in surveys: A review and synthesis. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

Tang, W., & Parish, W. L. (2000). Chinese urban life under reform: The changing social contract. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tiefer, L. (2000). Sexology and the pharmaceutical industry: The threat of co-optation. Journal of Sex Research, 37, 273–283.

Townsend, J. M., & Wasserman, T. (1997). The perception of sexual attractiveness: Sex differences in variability. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 243–268.

Trostle, L. (1993). Pornography as a source of sex information for university students: Some consistent findings. Psychological Reports, 72, 407–412.

Trudel, G., Turgeon, L., & Piché, L. (2000). Marital and sexual aspects of old age. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 15, 381–406.

Ventegodt, S. (1998). Sex and the quality of life in Denmark. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27, 295–307.

Waite, L., & Joyner, K. (2001). Emotional and physical satisfaction with sex in married, cohabiting, and dating sexual unions: Do men and women differ? In E. O. Laumann & R. T. Michael (Eds.), Sex, love, and health in America: Private choices and public policy (pp. 239–269). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Wang, J., Jiang, B., Siegal, H., Falck, R., & Carlson, R. (2001). Levels of AIDS and HIV knowledge and sexual practices among sexually transmitted disease patients in China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 28, 171–175.

Whipple, B. (2001). Women's sexual pleasure and satisfaction. Scandinavian Journal of Sexology, 4, 191–197.

Xu, A., & Ye, W. (1999). Zhongguo Hunyin Zhiliang Yanjiu (Studies on the Chinese marital quality). Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe.

Young, M., Denny, G., Young, T., & Luquis, R. (2000). Sexual satisfaction among married women. American Journal of Health Studies, 16, 73–85.

Zhou, M. (1993). A survey of sexual states of married, healthy reproductive age women. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 6, 15–28.

Acknowledgments

Primary funding support was provided by grant RO1 HD34157 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (William L. Parish, PI). Additional support was provided by grant P30 HD18288 to the University of Chicago from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Population Research Center, and grant P30 AI50410 to the University of North Carolina from the National Institutes of Health Fogarty Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parish, W.L., Luo, Y., Stolzenberg, R. et al. Sexual Practices and Sexual Satisfaction: A Population Based Study of Chinese Urban Adults. Arch Sex Behav 36, 5–20 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9082-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9082-y