Abstract

Given the enormous successes in treating HIV disease with antiretroviral therapies, there is a burgeoning population of healthy, sexually active HIV+ men and women. Because HIV prevention counseling has focused traditionally on persons at risk of becoming infected, there is an urgent mandate to explore ways to engage HIV+ persons in transmission risk reduction counseling. Using two case examples, this article presents an overview of motivational interviewing in a single counseling session as a promising treatment for addressing ambivalence about safer sex with HIV+ persons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This article describes a brief counseling intervention for HIV transmission risk reduction intervention for HIV+ persons. Following an overview of contemporary approaches to prevention with this population at different systems levels and a summary of the tenets of motivational interviewing, I describe a pilot study of a one-session motivational enhancement counseling intervention. The article uses two case examples to illustrate how HIV/AIDS case managers and other social workers or counselors might employ a low-burden approach to engage HIV+ persons in harm reduction for sexually transmitting HIV to their sexual partners.

Prevention approaches with HIV+ persons

“Prevention with positives” is an increasingly stressed component of HIV prevention programming in the United States, as demonstrated by Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2003) initiatives. Working with people who know they are HIV+ on strategies to reduce their risk of infecting others has long made sense (Kok, 1999); however, several factors have delayed translating basic approaches used for intervening with populations at risk for becoming HIV infected into techniques to be used with those at risk for infecting others. First, prior to greater availability of antiretroviral therapies (ARV), emphasis was placed on primary prevention of HIV. This emphasis was due to practical considerations. For example, many individuals discovered they were HIV+ only when they were identified as having an opportunistic infection (e.g., pneumonia) indicative of AIDS. Such persons were often considered too ill or weak to be sexually active.

Another factor was concern over “blaming victims,” and, as a result, considerable attention was paid to enacting protective legislation and nondiscriminatory public health practices. Despite advances made in protecting the civil rights of persons living with HIV/AIDS, stigma remains a formidable barrier to prevention and care services (Herek et al., 1998; Valdiserri, 2002). The stigma of AIDS prevents people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) from accessing social and health services because they wish to keep their HIV status a secret from health-care providers, families, and sex partners. Moreover, public discourse and legal issues may also reinforce stigma. As recently as March 2005, various pundits made innuendoes about quarantining people with HIV (Pinkerton, 2005), even though quarantining people has traditionally been legally sanctioned only in cases of communicable diseases that are easily spread. Finally, increasing numbers of persons with HIV are being prosecuted for not revealing their HIV status to sex partners who subsequently test HIV+ (Worth, Patton, & McGehee, 2005; for additional information about policy level interventions, see also Shriver, Everett, & Morin, 2000). These contexts likely have consequences for HIV disclosure to sexual partners and to social and health service practitioners.

It should be noted that, of the factors slowing the development of prevention with positives, one of the most significant has been complacency on the part of people living with HIV/AIDS as well as among traditional risk groups for infection (Valdiserri, 2004). For the latter, the development of ARV has led substantial numbers of persons at risk for HIV infection to minimize the seriousness of HIV infection because AIDS is now socially constructed to be a chronic and manageable health condition, like multiple sclerosis or diabetes, rather than a terminal disease (Bayer & Oppenheimer, 2000; Valdiserri, 2004). And for some people living with HIV, learning that they are HIV+ is an opportunity to abandon notions of safer sex, because for them, “It's too late anyway.” Finally, agencies providing AIDS services have themselves been barriers to risk reduction among their HIV+ clients. AIDS service organizations (ASOs) have long assumed that persons with HIV will not attend prevention programs for the reasons described above. However, it appears that, until recently, ASOs hired case managers primarily to assist people living with HIV/AIDS in acquiring and maintaining social and medical services and welfare benefits. Such staff are often unready and untrained to counsel individuals about their sex lives (Mitchell & Linsk, 2001). In short, prevention and care services are bifurcated.

Despite the growing emphasis on prevention with positives in the United States and the increasing numbers of HIV infected persons leading longer and sexually active lives, many agencies serving people with HIV/AIDS may be unprepared to roll out community or group-level programs because of the difficulty in obtaining resources and training providers with available curricula. Perhaps the biggest barrier, however, is recruiting participants given AIDS stigma and complacency. Multi-session individual counseling approaches obviously have their own burden with staffing.

There is a growing literature describing and testing a variety of approaches to prevention with positives, including community, group, and individual interventions. Perhaps least (empirically) tested and most politically scrutinized efforts are those by the HIV+ community to change attitudes about complacency for prevention. Social marketing has been utilized to disseminate messages via newspaper, Internet, radio, and television within communities about the realities of living with HIV and pro-actively integrating prevention messages. One example are multilingual versions of the program titled “HIV Stops with Me,” which features spokespersons giving testimonials about their lives living with HIV and challenging others to live and act safely (Palmer, 2004; see also http://www.hivstopswithme.org/). Although such programs are promising for reinforcing norms to reduce transmission of HIV, they are also prone to scrutiny given their sex-positive approaches. For example, the San Francisco based version of “HIV Stops with Me” received heavy criticism by members of the U.S. Congress for their sex-positive messages from gay, bisexual, and transgender spokesmodels and was threatened with having $500,000 of CDC funding stripped (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2003).

Support groups have been a mainstay in the provision of care for people living with HIV/AIDS since the beginning of the pandemic. For the most part, these groups provide advocacy and comfort–with the goal of empowerment–to persons coping with AIDS and its impact on social functioning. More recently, group level counseling interventions have been tested for their effectiveness in guiding HIV+ persons toward transmission risk reduction with sexual and drug-sharing partners. These groups range in numbers of session (e.g., as few as 5 or as many as 11) and have been used with populations identified by gender, age, and transmission-risk category. The interventions can focus on learning about safer sex or drug injection harm reduction, developing coping strategies for safer sex, status disclosure, and skill building to enhance self-efficacy. These programs have been demonstrated to have a range of effectiveness from preliminary evidence of efficacy with injection drug users (Margolin, Avants, Warburton, Hawkins, & Shi, 2003) to being disseminated as model programs by the CDC (Kalichman et al., 2001). However, as Rotheram-Borus et al. (2001) noted, while group participants tend to become safer and healthier, alternative formats are needed to counter the stigma or other constraints to attendance for the sizable number of individuals who won't attend group sessions.

Individual approaches include HIV prevention case management (Gasiorowicz et al., 2005; Purcell, DeGroff, & Wolistksi, 1998) and transmission risk reduction interventions directed at discrete target groups of PLHA, including youth, racial/ethnic groups, men being released from prison, and persons with hemophilia (Wolitiski, Janssen, Onorato, Purcell, & Crepaz, 2005). In general, individual approaches provide education about and behavioral reinforcement for transmission risk reduction. Evidence is accumulating to indicate efficacy of these approaches, some of which are now being tested in randomized clinical trials.

A longstanding concern of implementing risk reduction programs is that they are not always optimally designed for persons ambivalent about behavior change. In response, there is a growing literature on the use of motivational enhancement therapy for both brief and extended individual HIV risk reduction counseling, including therapy for HIV+ persons and individuals with co-morbidity with alcohol or drug problems (see, e.g., Baker, Kochan, Dixon, Heather, & Wodak, 1994; Beadnell et al., 1999; Koblin, Chesney, Coates, & EXPLORE Study Team, 2004; Picciano, Roffman, Kalichman, Rutledge, & Berghuis, 2001; Ryan, Fisher, Peppert, & Lampinen, 1999). Such counseling interventions have been developed partly in response to evidence that motivational enhancement therapy is effective for a broad range of problem health behaviors, including obesity, medication schedule noncompliance for diabetes, and substance abuse (for reviews, see Dunn, Deroo, & Rivera, 2001; Nahom, 2005).

Brief motivational enhancement therapy: Primary tenets

Motivational enhancement therapy is concerned primarily with motivating individuals who feel ambivalent (or “stuck”) about a behavior change or are assessed by counselors as “resistant” by assisting them in identifying their thoughts and feelings about change, considering a range of strategies for change when they are ready, accepting personal responsibility, and preparing for change or its maintenance by becoming behaviorally self-efficacious. A first step toward assisting such individuals is in identifying their placement on the spiraling continuum of the stages of change (Prochaska, Redding, Harlow, Rossi, & Velicer, 1994). Used as an assessment tool, the stages of change model can assist counselors in determining what sorts of professional interactions may be useful. For example, persons in early stages of change may benefit from strategies designed to increase their awareness of the need for change, whereas persons who wish to enact change may better benefit from confidence building brought on by successful practice of transmission risk reduction strategies. A “one size fits all” approach to prevention counseling, including motivational enhancement therapy, may cause more harm than good by not tailoring counseling encounters to clients with various needs.

Motivational interviewing is often adopted as the primary counseling strategy in motivational enhancement therapy approaches. Widely associated with the work of Miller and Rollnick (2002; Rollnick, Mason, & Butler, 2000), it was developed to supplant other forms of treatment where clients were assumed–often erroneously–to be ready for change because they were in alcohol or other drug treatment programs. Building on the spirit of client self-determination, motivational interviewing has four principles for successfully engaging persons unready for or resistant to change: expressing empathy, developing discrepancies between current and desirable attitudes and behavior, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy.

Expressing empathy

Although requisite in many counseling approaches, the expression of empathy often falls short in sessions, especially when the counselor is working with clients engaging in socially undesirable behavior, such as unprotected intercourse absent disclosure of HIV+ status. Counselors must make conscious efforts to become mindful of their own stigmatizing attitudes about HIV so they are prepared to provide unconditional positive regard for clients expressing ambivalence about behavior that may lead to infecting others with HIV. From the perspective of motivational interviewing, expressing empathy means using reflective listening to enhance a client's understanding of ambivalence, commitment toward change, and fears.

Developing discrepancies

It is not unusual for persons to persist with potentially harmful behavior in spite of wishing not to do so. For these persons, enhancing self-awareness of the costs and benefits of maintaining current practices versus moving toward important personal goals is helpful. Rather than forcing awareness, however, counselors should utilize feedback to highlight apparent discrepancies between actual and desired behavior. Thus, developing discrepancies should be aimed at eliciting change statement from clients. Focusing on contradictions can become sticking points wherein clients may view counselors as pressuring them. As reflected in the next principle, avoiding argumentation is paramount in motivational interviewing.

Rolling with resistance

Social networks and sociopolitical forces can engender resistance when they oppose specific behaviors. Counselors can unwittingly reinforce client resistance when they are seen as agents of public policy or public health. Thus, counselors should be wary of using labels or directly acknowledging resistance. Resistance may be manifested as argumentation, denial, or challenges. Rather than being opposed to change, clients may simply feel misunderstood. At the initial sign of resistance, counselors should recognize this as an opportunity for growth rather than an obstacle to overcome. To assist clients in arguing for change (the desired side of ambivalence) rather than protecting current behavior (the undesired side of ambivalence), a number of strategies can be utilized, including reframing defensive statements, and amplified or double-sided reflections.

Supporting self-efficacy

Counselors should build on their expressions of empathy by expressing optimism for client-generated statements of desire for change. Upon hearing commitment to change, counselors should assist their clients in assessing their abilities to enact behavioral strategies as well as helping the client become more confident about executing planned actions or using coping responses. Of course, previous successes in change efforts for the current problem or past concerns with other issues can be the foundation for bolstering client confidence.

Protocol of intervention

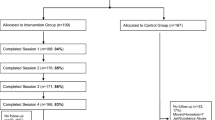

Building on past work by Picciano et al. (2001) and Ryan et al. (1999), a one-session counseling intervention was developed to be delivered to HIV+ male and female clients of a regional ASO in North Florida as part of a small feasibility pilot trial. Procedures for protecting human participants were approved by university internal review board. Flyers announcing a “research study for exploring thoughts and feelings about having HIV and being sexually active” were distributed in the lobby of the ASO and directly to clients by case managers. The flyers directed clients to telephone the researcher directly; there was no cross-referencing with the ASO. Eligibility–screened by telephone–was indicated by self-identifying as HIV+, being 18 years or older, and having had oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse within the past two months with a partner who was HIV-negative, with more than one partner, or within a monogamous HIV serostatus concordant relationship of less than one year. Counseling sessions were held face-to-face by the author in his university office and participants received a $25 incentive with a $10 two-month post-assessment. Persons were able to participate anonymously (no identifying information whatsoever collected) or confidentially (minimal contact information collected for the purpose of providing an appointment reminder telephone call).

The session was comprised of three major components: (1) a client-completed written assessment about sexual activity and related attitudes; (2) a semi-structured review of the assessment data using principles of motivational interviewing; and (3) establishing how the client foresaw using the information.

The sessions began by reviewing informed consent procedures, wherein participants were apprised of their rights and responsibilities in research. The researcher stressed that no one else would have access to the information participants shared, including case managers and supervisors at the cooperating ASO. Then, participants were invited to complete a questionnaire including information about their health status, attitudes about sex, attitudes about safer sex including HIV status disclosure, HIV transmission risks, stage of change for disclosing their HIV status and for having sex only with other HIV+ people, and alcohol and other drug use. When they completed that questionnaire, they were engaged in a partner recall method of their four most recent sex partners (within the previous two months) and asked to complete a brief questionnaire about them. Most participants completed the assessment portion of the session within one-half hour. Upon conclusion, participants were offered a snack and beverage and the opportunity to take a break to stretch their legs or use the restroom. This allowed an opportunity for the researcher-counselor to review the questionnaires to prepare for the next component of the session.

Following the break (5–10 min), the active counseling component began with the counselor asking the participant what his or her thoughts were about having to complete the questionnaire. This was intended to serve as an opportunity for the client to voice any preliminary statements about her or his behavior and concerns and for the counselor to express empathy. Next, the counselor conducted a semi-structured review of the following foci from the questionnaires: (1) HIV status of recent partners; (2) sexual activity–protected and unprotected; (3) attitudes about condoms; (4) transmission risks; (5) disclosure attitudes and practice; (6) responsibility and seriousness of infecting others; and (7) alcohol and other drug use. Rather than strictly following a guided review of each component of the assessment (as done with a personal feedback report in the check-up modality, see Rutledge et al., 2001), the counselor provided a summary of the various foci and asked the participant to elaborate. For example, in reviewing the data about sexual activity, the counselor would simply state, “You indicated having used condoms with some partners, but not others. Tell me more about that.” In so doing, participants sometimes pointed out discrepancies between their behavior and their attitudes, between their current behavior and their hopes for the future, and so forth. Rather than directly confronting the participants with these contradictions, the counselor simply “noticed” such differences aloud.

Depending on the identified stage of change related to disclosure and partner choice (indicated by responses in the assessment questions), the counselor utilized the remaining time to build toward the final component, which was to establish direction for how the participant anticipated using the information. Persons at earlier stages of change in transmission risk reduction often identified that, although interesting, they did not see any way to use the information. Others farther along the continuum of change typically voiced the desire to think more about their behavior as persons living with HIV and expressed interest in gaining additional support to make such changes. Individuals already practicing transmission risk reduction emphasized appreciation for being able to tell their stories and, occasionally, a desire to be supportive to other HIV+ people. This final component of the session was an opportunity for the counselor to re-emphasize empathy for ambivalence, identify avenues for change or support, or express confidence in the participant.

Case Examples

The primary goal of the study was to determine the feasibility of attracting participants and piloting the assessment and counseling activities as designed. In all, in the period of 4 weeks, 22 men and women called for more information about the study and 15 participated in the intervention. From this sample, two cases were selected as representative to highlight the use of brief motivational enhancement therapy for HIV transmission risk reduction with persons at different stages of change. Names have been changed to protect the participants’ identities.

Paul, a 45-year-old gay man, has been healthy throughout his 15 years of being HIV+. He credits his health to not doing illegal drugs and to having a good relationship with his physician, who reportedly is knowledgeable about ARV. His brief questionnaire revealed he had recently had sex with six partners in the past two months, including a 19-year-old man to whom he described himself as becoming quite attached. Like the other five men, Paul had met this sex partner in a gay bar and not disclosed his own HIV status nor asked about his. He used condoms inconsistently with each of the four partners, but was concerned only for the welfare of the 19-year-old, whom he described as recently out of the closet. He was assessed at being in the contemplative stage of change regarding adjusting his condom use and the precontemplative stage for disclosing his HIV status to sexual partners. He emphasized that he never discloses his HIV status because he felt he cannot trust others given the many times he had overheard friends and acquaintances whispering about the perceived HIV status of other gay men. He felt the need to control this information because he had kept his HIV status a secret from his family for the past 15 years.

Rapport was quickly built with brief empathic reflections as Paul presented as desiring to think through his mixed feelings about condom use. In describing his safer-sex philosophy, Paul explained that he feels sex is a 50–50 responsibility and that he would prefer to use a condom every time he was the “top” (inserting his penis into a male partner's anus). However, he rationalized that because gay and bisexual men have been around AIDS so long that if sex partners are aggressive about unsafe sex, he does not use condoms, but will withdraw before ejaculating. In response to a gentle empathic summary, Paul responded by reinforcing his rationalization with statements that he generally has little pre-ejaculate and that he had a 10-month unsafe relationship with an HIV negative man who did not seroconvert.

Motivational interviewing principles suggest addressing such obvious rationalizations might be construed as argumentation and met with resistance with which to dance rather than confront. Thus, for the moment, the focus shifted to exploring the inconsistencies by partner in condom use. Paul explained that conversations about using condoms really depend on the other person. A double-sided reflection was used to expose the discrepancy with the earlier statement about 50–50 responsibility. At this point, Paul explained that his age cohort of gay men had supported one another in the early days of AIDS and adopted the practice of assuming everyone was HIV+ and acting accordingly. This, he now acknowledged, was not really a 50–50 responsibility, but more of a personal responsibility to protect oneself. In a quiet moment, Paul realized that there might well be intergenerational differences in communication: the young man to whom he was becoming attached might not be asking for condoms because he assumed–like other young HIV negative persons–that people with HIV would always use condoms to prevent transmission. This moment represented a potential point of decisional balance for Paul in environmental and self-re-evaluation. Accordingly, the balance of time in the session was spent shoring up the pros of condom use as personal responsibility and subtly chipping away at the cons of constructing safer sex as a shared responsibility.

The session ended with Paul's expression of appreciation for being able to talk with someone about these concerns rather than mulling them over by himself. He said that he was unlikely to change his philosophies about condom use and disclosure in general. However, he did plan to either cut off the budding romantic relationship with the 19-year-old or spend more time getting to know him to build a sense of trust. Regardless, he was committed to either always using condoms with this partner or not having sex with him at all.

Jeremiah, a 25-year-old heterosexual man, had been HIV+ about nine months prior to the counseling session. The session did not begin smoothly as Jeremiah appeared distracted and uncomfortable with the university setting. He was quite concerned that if the information he discussed about his sexual behavior were reported to his ASO case manager, the agency would withdraw financial support. Following a brief discussion reinforcing the statements about confidentiality in the informed consent form and empathic expressions reflecting his anxiety, Jeremiah agreed to complete the brief self-administered assessment.

After completing the assessment, Jeremiah responded to the standard opening query of what it was like to fill it out with a statement that he wished to proceed quickly through the rest of the session because he was not sure that it was going to be helpful. Further, he stated he had only 20 more minutes before he needed to catch a bus and just wanted to know what the researcher-counselor thought of his sexual behavior.

Because time was short and the client was openly resistant, the counselor elected to roll with this resistance by providing quick feedback about the assessment data. According to his brief assessment data, he had disclosed his HIV status to only a few select people and was in the contemplative stage for always disclosing his HIV status to sex partners. He reported having had vaginal and oral sex with one woman about 30 times in the past two months. Assessment data suggested Jeremiah endorsed the notion of safer sex as a way to protect sexual partners. The counselor summarized that it appeared that although Jeremiah believed it would be wrong to infect others with HIV, he had mixed feelings about using condoms and always disclosing his HIV status to sexual partners.

In response, Jeremiah explained the benefits of using condoms are that they prevent people from getting HIV and feeling good about himself for using them. The negative effects of condoms were decreased sexual spontaneity and difficulty maintaining an erection while putting one on. He said he was committed to using condoms as long as the partner did not refuse, but that he felt it was likely he would have unprotected sex with women who rejected safer sex because if he did not, someone else would anyway.

To explore further how the desire to have sexual intimacy was influencing the discrepancy of ideal vs. current behavior regarding using condoms to avoid transmission, the counselor asked Jeremiah to recount the decision making with his one sexual partner of the previous two months. He emphasized tersely that he always uses condoms with her because that is what she prefers. According to Jeremiah, she was not someone with whom he foresees having a long-term relationship beyond sexual encounters because she was involved with another man who did not know she was also seeing Jeremiah. He said he regrets having told her he was HIV+ when he first met her because she would never leave her boyfriend for someone with HIV. Thus, he was uncertain about always disclosing his HIV status to sexual partners. He stated that he would really like to get married some day, but he felt like “damaged goods”–that no woman would ever want for the long run. His primary conflict was thus revealed: although he felt he was morally obligated to do the right thing with women by not only using condoms but also disclosing his HIV status, he worried many women would turn him down for sex and not consider him “marriage material” for doing so.

Because the session needed to move to a close given the participant's schedule, the counselor asked what Jeremiah would do with information he had shared. By this time, his gruffness had softened considerably. He responded that it just reminded him that his life options were limited, but that he was far from dead. He recalled a question from the assessment about only having sex with other HIV+ persons as a safer sex strategy and wondered if it might be possible to meet HIV+ women who would not reject him because of his health status. The session closed with a referral to two local support groups where Jeremiah could share his concerns with others who had traveled a similar path.

Discussion

In both cases, the men expressed ambivalence in communicating their HIV status and using condoms with prospective or current sexual partners. In traditional HIV prevention counseling or conversations with medical personnel, this ambivalence might often be met with stern statements that people with HIV must always use condoms to protect others. Unfortunately, this unempathic response often triggers an immediate internalized response from HIV+ men and women: that someone with HIV obviously did a lousy job of protecting them from HIV. Moreover, in gay men's communities, preventing HIV transmission has long been designated as primary prevention, that is, something for which uninfected persons take responsibility. Thus, space must be provided for HIV+ people, regardless of how long they have been infected, to grapple with these feelings of responsibility.

Although few HIV+ persons wish to transmit HIV intentionally, the stigma of the disease continues to silence many persons from communicating about it. Both men described fears of rejection. Developing the strength to reveal a stigmatized health condition and deal with the aftermath of disclosure requires time. Depending upon stage of readiness, follow up to brief motivational enhancement could include assisting individuals with referrals to support groups or individual cognitive behavioral skills building counseling.

A critique of motivational enhancement counseling for HIV transmission is that it does not necessarily lead directly to reduced transmission risk, including consistent condom use or sexual abstinence. This critique should be refocused on the actual aim of the counseling intervention: to engage persons in a discussion about ambivalence to propel them through stages of change of behavior. In the case of Paul, he was prompted to think through his philosophy about condom use by his feelings for someone he saw as vulnerable. Although he admitted that he is not likely to change his overall behavior, he indicated movement in viewing transmission risk reduction as somewhat more than a 50–50 responsibility for himself. In the case of Jeremiah, his desire to meet other HIV+ people through a support group may assist him in seeing other persons living with HIV who wish to develop long-term romantic relationships. Thus, brief motivational enhancement can be conceptualized as providing focused energy to sort through mixed feelings and offering linkage to other support or counseling services.

Given the promise of motivational enhancement and the increasing emphasis (political and practical) on prevention with positives, it is imperative to continue to test such innovations like the one described in this article in rigorous randomized control trials. In addition, such interventions should be adapted for effectiveness trials with ASOs or medical settings specializing in providing treatment for HIV disease. There are increasing numbers of front-line workers being exposed to motivational interviewing as a counseling style in their educational programs as well as at conferences. However, it is critical to determine the training needs and capacity of staff with a variety of professional experience and training (from paraprofessionals without bachelor's degrees to new professionals with recent bachelor's degrees to advanced professionals with master's and doctoral degrees) to deliver interventions like this one effectively given the constraints of high caseloads and traditional concerns about client complacency.

References

Baker, A., Kochan, N., Dixon, J., Heather, N., & Wodak, A. (1994). Controlled evaluation of a brief intervention for HIV prevention among injecting drug users not in treatment. AIDS Care, 6, 559–570.

Bayer, R., & Oppenheimer, G. M. (2000). AIDS doctors: Voices from the epidemic. New York: Oxford.

Beadnell, B., Rosengren, D., Downey, L., Fisher, D., Best, H., & Wickizer, L. (1999, August 31). Motivational interviewing to facilitate reduced HIV risk among MSM alcohol users. Paper presented at the National HIV Prevention Conference, Atlanta, GA.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003). Advancing HIV prevention: New strategies for a changing epidemic–2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 52, 329–332.

Dunn, C., Deroo, L., & Rivera, F. P. (2001). The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: A systematic review. Addiction, 96, 1725–1742.

Gasiorowicz, M., Llanasm, M. R., DiFranceisco, W., Benotsch, E. G., Brondino, M. J., Catz, S. L., et al. (2005). Reductions in transmission risk behaviors in HIV-positive clients receiving prevention case management services: Findings from a community demonstration project. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17(1 Suppl. A), 40–52.

Herek, G. M., Mitnick, L., Burris, S., Chesney, M., Devine, P., Fullilove, M. T., et al. (1998). Workshop report: AIDS and stigma: A conceptual framework and research agenda. AIDS Public Policy Journal, 13, 36–47.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2003, June 16). CDC asks AIDS project to discontinue ‘controversial’ HIV prevention programs. Kaiser Daily HIV/AIDS Report. Retrieved November 10, 2005, from Http://www.kaisernetwork.org/daily_reports/print_ report.cfm?DR_ID= 18279&dr_cat=1.

Kalichman, S. C., Rompa, D., Cage, M., DiFonzo, K., Simpson, D., Austin, J., et al. (2001). Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 21, 84–92.

Koblin, B., Chesney, M., Coates, T., & EXPLORE Study Team (2004). Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: The EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet, 364, 41–50.

Kok, G. (1999). Targeted prevention for people with HIV/AIDS: feasible and desirable? Patient Education and Counseling, 36, 239–246.

Margolin, A., Avants, S. K., Warburton, L. A., Hawkins, K. A., & Shi, J. (2003). A randomized clinical trial of a manual-guided risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive injection drug users. Health Psychology, 22, 223–228.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Mitchell, C. G., & Linsk, N. L. (2001). Prevention for positives: Challenges and opportunities for integrating prevention into HIV case management. AIDS Education and Prevention, 13, 393–402.

Nahom, D. (2005). Motivational interviewing and behavior change: How can we know it works? Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 2, 55–78.

Palmer, N. B. (2004). “Let's talk about sex, baby”: Community-based HIV prevention work and the problem of sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33, 271–275.

Picciano, J. F., Roffman, R. A., Kalichman, S. C., Rutledge, S. E., & Berghuis, J. P. (2001). A telephone-based brief intervention to reduce sexual risk taking among MSM: A pilot study. AIDS and Behavior, 5, 251–262.

Pinkerton, J. (2005, March 3). Darwin's war on political correct-ness. Retrieved November 10, 2005, from http://www.techcentralstation.com/030305B.html.

Prochaska, J. O., Redding, C. A., Harlow, L. L., Rossi, J. S., & Velicer, W. F. (1994). The transtheoretical model of change and HIV prevention: A review. Health Education Quarterly, 21, 471–486.

Purcell, D. W., DeGroff, A. S., & Wolitski, R. J. (1998). HIV prevention case management: Current practice and future directions. Health and Social Work, 23, 282–289.

Rollnick, S., Mason, P., & Butler, C. (2000). Health behavior change: A guide for practitioners. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Lee, M. B., Murphy, D. A., Futterman, D., Duan, N., Birnbaum, J. M., et al. (2001). Efficacy of a preventive intervention for youths living with HIV. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 400–405.

Rutledge, S. E., Roffman, R. A., Mahoney, C., Picciano, J. F., Berghuis, J. P., & Kalichman, S. C. (2001). Motivational enhancement counseling strategies in delivering a telephone-based brief HIV prevention intervention. Clinical Social Work Journal, 29, 291–306.

Ryan, R., Fisher, D., Peppert, J., & Lampinen, T. (1999, August 31). Pilot results of a brief intervention to reduce high-risk sex among HIV seropositive gay and bisexual men. Paper presented at the National HIV Prevention Conference, Atlanta, GA.

Shriver, M. D., Everett, C., & Morin, S. F. (2000). Structural interventions to encourage primary HIV prevention among people living with HIV. AIDS, 14(Suppl. 1), S57–S62.

Valdiserri, R. O. (2002). HIV/AIDS stigma: An impediment to public health. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 341–342.

Valdiserri, R. O. (2004). Mapping the roots of HIV/AIDS complacency: Implications for program and policy development. AIDS Education and Prevention, 16, 426–439.

Wolitiski, R. J., Janssen, R. S., Onorato, I. M., Purcell, D. W., & Crepaz, N. (2005). An overview of prevention with people living with HIV. In S. C. Kalichman (Ed.), Positive prevention: Reducing HIV transmission among people living with HIV/AIDS (pp. 1–28). New York: Kluwer.

Worth, H., Patton, C., & McGehee, M. T. (2005). Legislating the pandemic: A global survey of HIV/AIDS in criminal law. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 2(2), 15–22.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rutledge, S.E. Single-Session Motivational Enhancement Counseling to Support Change Toward Reduction of HIV Transmission by HIV Positive Persons. Arch Sex Behav 36, 313–319 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9077-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9077-8