Abstract

The tomato red spider mite, Tetranychus evansi, is reported as a severe pest of tomato and other solanaceous crops from Africa, from Atlantic and Mediterranean Islands, and more recently from the south of Europe (Portugal, Spain and France). A population of the predaceous mite Phytoseiulus longipes has been recently found in Brazil in association with T. evansi. The objective of this paper was to assess the development and reproduction abilities of this strain on T. evansi under laboratory conditions at four temperatures: 15, 20, 25 and 30°C. The duration of the immature phase ranged from 3.1 to 15.4 days, at 30 and 15°C, respectively. Global immature lower thermal threshold was 12.0°C. Immature survival was high at all temperatures tested (minimum of 88% at 30°C). The intrinsic rate of increase (r m) of P. longipes ranged from 0.091 to 0.416 female/female/day, at 15 and 30°C, respectively. P. longipes would be able to develop at a wide range of temperatures feeding on T. evansi and has the potential to control T. evansi populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The phytophagous mite Tetranychus evansi Baker and Pritchard is found mainly on solanaceous plants such as tomato, eggplant and tobacco (Bolland et al. 1998). It is reported as a severe pest in tomato crop in Africa (Saunyama and Knapp 2003). It has been more recently found in Southern Europe (Ferragut and Escudero 1999; Bolland and Vala 2000; Aucejo et al. 2003; Migeon 2005; Castagnoli et al. 2006; Palevsky, pers. comm.). Resistance to various acaricides has been reported (Blair 1989), and predators commonly used against other spider mite pests, especially Tetranychus urticae Koch, are inefficient to control this species (Moraes and McMurtry 1985, 1986; Escudero and Ferragut 2005). Surveys for biological control agents in the suspected area of origin of T. evansi (Argentina and Brazil) have been conducted (Furtado et al. 2006b, in press), and a phytoseiid mite species, Phytoseiulus longipes Evans, has been found in association with T. evansi (Furtado 2006).

Previous predation tests suggested the ineffectiveness of a South African population of P. longipes in controlling T. evansi (Moraes and McMurtry 1985) but tests conducted with the Brazilian strain suggested it to be very promising (Furtado 2006). In order to optimize the use of this species in biological control, data concerning its development at different temperatures are needed. The aim of the present study was to determine life tables of P. longipes feeding on T. evansi at four temperatures (15, 20, 25 and 30°C). The temperature range selected is common in greenhouses (Zhang 2003), and is known to be favorable to the development of T. evansi (Moraes and McMurtry 1987; Bonato 1999).

Material and methods

Experimental conditions

The specimens of P. longipes used in this study were obtained from a colony initiated with specimens collected in March 2004 in Uruguaiana (29° 32′ 69′′ S, 56° 32′ 06′′ W), State of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) (Furtado 2006). The colony was fed with a mixture of T. urticae, offered on leaves of Canavalia ensiformis (L.) DC., placed on a plastic sheet (PAVIFLEX®) laid on a piece of foam mat in a plastic tray (25 × 17 × 9 cm). The margins of the plastic plate were covered with a 1-cm-wide band of cotton wool, to prevent mite escape. Plastic trays were kept in incubators at 25°C, 80 ± 10% RH and 12:12 [L:D] photoperiod.

The T. evansi stock colony was initiated with specimens collected from a tomato field at Piracicaba (22° 41′ 72′′ S, 47° 38′ 48′′ W), State of São Paulo (Brazil), and reared on Solanum americanum Miller and Lycopersicon esculentum Miller in screen cages.

The T. urticae stock colony initiated with specimens collected in Piracicaba (22° 41′ 72′′ S, 47° 38′ 48′′ W), State of São Paulo (Brazil), was reared on C. ensiformis in screen cages.

Immature development

The following steps were performed at 15, 20, 25 or 30°C, at 80 ± 10% RH and with a 12:12 [L:D] photoperiod. Groups of five to eight T. evansi females were placed in experimental units, consisting of a leaf disk of S. americanum (2 cm in diameter) placed underside up onto a moist disk of filter paper inside a Petri dish (2 cm in diameter, 1 cm high) using a thin paintbrush. Two days later, when 20–30 eggs of T. evansi had been laid, an egg of P. longipes (between 0 and 6 h old) was taken from the intermediate stock colony (consisting in 30–50 females reared on a leaf of C. ensiformis placed in a plastic tray as described above) and transferred to each experimental unit every 6 h. Each unit was then closed with a transparent plastic film. To maintain humidity, distilled water was added on the filter paper every day. Periodically (from 2 to 3 days at 30°C to 7 days at 15°C) P. longipes individuals were transferred to new leaves infested with T. evansi as previously reported.

Observations have been carried out every 8 h to determine the duration and the survivorship for each stage.

Lower thermal threshold (TD) was calculated as a/b, where a and b are determined by the following linear regression: DR = a + bT, where DR is the development rate per day, T the temperature in °C and a and b the regression coefficients (Bonato 1999).

Reproduction

Recently emerged adult P. longipes females obtained were transferred to new experimental units. A male taken from the stock colony was then added to each unit containing one female. At least 30 couples were observed at each temperature. Daily observations were conducted to determine female fecundity and survivorship. The eggs laid were placed together daily in a single unit and reared to adulthood to determine the secondary sex ratio (female percentage of the studied female cohort offspring).

Life table

The life table was constructed considering the females of the cohort studied. The net reproductive rate (Ro), the mean generation time (T), the intrinsic rate of increase (r m), the doubling time (D t), and the finite rate of increase (λ) were calculated using the method recommended by Birch (1948):

-

Ro = ∑ (l x × m x )

-

T = ∑ (x × l x × m x )/∑ (l x × m x )

-

r m = Ln (Ro)/T

-

D t = Ln (2)/r m

-

λ = exp (r m)

Here x is age (with 0.5 for the day when eggs had been laid), l x , the cumulative female survivorship, and m x , the number of female descendants per female at x.

Calculation of a corrected r m value was performed by iteration. The method, aiming to find r m for which (1 − ∑ exp (−r m × x) × l x × m x ) is minimal, was given by Maia et al. (2000).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and related Tukey HSD mean comparison tests were performed to determine differences between duration of the immature phases and adult stages at the four temperatures tested (R project 2006).

Results

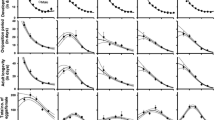

Immature development

Increasing temperatures significantly decreased the duration of all stages. The egg stage was the longest for each temperature tested, decreasing from 5.9 days at 15°C to 1.1 days at 30°C. The larval stage was the shortest, varying from 1.5 day at 15°C to 0.4 day at 30°C. The durations of the protonymphal and deutonymphal stages were about the same, within each temperature tested. Duration of the whole immature phase (egg to adult emergence) decreased from 15.4 days at 15°C to 3.1 days at 30°C (Table 1).

At 15 and 20°C, 96 and 95% of the immatures survived, respectively. The lowest mortality occurred at egg stage. At 25°C, all mites reached the adult stage. The lowest immature survival rate was observed at 30°C (88%) and concerned all immature stages. Lower thermal thresholds (TD) were calculated for each immature stage and for the whole immature phase (Table 2). TD ranged from 10.2°C for the larval stage to 12.6°C for the egg stage.

Reproduction

As previously observed for immature development, the longevity of adults was highest at 15°C and decreased as the temperature increased (Table 3). The pre-oviposition period ranged from 3.1 to 0.5 days (maximum was 3.3 at 20°C), oviposition from 17.0 to 6.8 days, post-oviposition from 6.2 to 1.3 days and longevity from 43.8 to 13.1 days, at 15 and 30°C, respectively.

A reverse tendency was observed for daily oviposition and fecundity rates, which ranged from 0.3 to 1.7 and 14.9 to 26.4 eggs per female at 15 and 30°C, respectively.

The secondary sex ratio was 0.85, 0.83, 0.78 and 0.82 at 15, 20, 25 and 30°C, respectively.

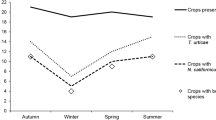

Life table

Calculated life table parameters are given in Table 4. Concurrently with the tendency observed for duration of immature and adult stages, a trend towards lower values of mean generation time and doubling time was observed from the lowest to the highest temperatures. Congruently with those trends and with the observed higher rates of oviposition at higher temperatures, intrinsic rates of increase (iterative method) and finite rates of increase raised from 0.091 to 0.416 female/female/day and from 1.09 to 1.53, from 15 to 30°C, respectively. The net reproductive rate increased progressively from 15 to 25°C, and remained about the same at 25°C and 30°C.

Discussion

Up to 2005, data on the biology of P. longipes concerned a strain from South Africa (Badii 1981; Badii and McMurtry 1983; Takahashi and Chant 1992, 1994), reported as not effective to control T. evansi (Moraes and McMurtry 1985). Furtado et al. (2006a, submitted) reported for the first time data on the biology of the strain from Brazil.

The present study confirms previous observations about the ability of the Brazilian strain of P. longipes to develop feeding on T. evansi (Furtado 2006). The larvae did not feed, thus no food was required to reach the protonymphal stage, as it is the case in many Type I phytoseiids as defined by McMurtry and Croft (1997), especially species of the genus Phytoseiulus. It has been observed, as previously by Furtado et al. (2006b, in press), that other stages of this species are neither hampered by T. evansi webbing nor by tomato trichomes. These observations could make P. longipes a preferential biocontrol agent against T. evansi populations.

Generally, demographic parameters from different studies are difficult to compare, as differences could be due to strains as well as to experimental methodology variations, for instance size and type of arenas, food provided, relative humidity, photoperiod and differences in calculations method.

The duration of the immature stages of P. longipes feeding on Tetranychus pacificus (McGregor), Oligonychus punicae (Hirst) and Panonychus citri (McGregor) were lower at 20, 25 and 30°C for the South African strain than for the Brazilian (Badii 1981; Badii and McMurtry 1983; Takahashi and Chant 1992). The latter seems to have a greater development ability than the South African populations at these temperatures, feeding on T. evansi. Development durations mentioned by Furtado et al. (2006a, submitted) were very close to those reported in this paper, for all immature stages.

The egg stage was the most sensitive to low temperatures, as it has the highest TD value (12.6°C). Lower thermal threshold values are similar to those of other phytoseiids. For instance, Gotoh et al. (2004) reported a TD of 10.3°C from egg to oviposition for Neoseiulus californicus (McGregor), while in the present work TD for immature development was 12°C. Phytoseiulus longipes has been reported from various regions of the world where low temperatures are very common during the winter, such as North Argentina, North Chile, South Africa, Zimbabwe (Moraes et al. 2004) and now Southern Brazil (Furtado 2006). The rapid development of the Brazilian strain of P. longipes feeding on T. evansi and its ability to develop during cold periods suggest that it would perhaps survive in temperate climates in Africa and Europe.

As for immatures, important differences were also found between previous data and the present results concerning the duration of the adult phases of P. longipes. At 25°C, Badii (1981) reported for the South African population an oviposition phase of 20.8 days feeding on T. pacificus versus 11.1 days in the present study. Takahashi and Chant (1992) reported an oviposition phase of 10.9 at 26°C feeding also with T. pacificus as prey.

Values of r m obtained by Badii (1981) and Takahashi and Chant (1994) for the South African strain of P. longipes were higher than in the present study, with 0.366 at 25°C and 0.465 at 26°C, respectively. Along with the origin of the P. longipes strains tested, the methodology and the food provided, the calculation of the secondary sex ratio could explain those differences. Badii (1981) and Takahashi and Chant (1994) based their estimation of the sex ratio on the generation considered in their studies for immature development, while in the present study calculations were made from the offspring of the generation considered for immature development. This difference leads to an underestimation of the r m in the present paper compared to the others cited above.

Similar values of r m as obtained in this paper are reported in the literature for other phytoseiid species (Sabelis 1985), for instance for Amblyseius longispinosus (Evans) (Kolodochka 1983, in Sabelis, 1985), for Amblyseius deleoni Muma and Denmark (Saito and Mori 1981, in Sabelis 1985) and for N. californicus (Ma and Laing 1973). On the other hand, they are very low compared to other Type I species as defined by McMurtry and Croft (1997). At 26°C, for Phytoseiulus persimilis Athias-Henriot, Phytoseiulus macropilis (Banks) and Phytoseiulus fragariae Denmark and Schicha, Takahashi and Chant (1994) reported r m-values of 0.4282, 0.3862 and 0.3263, respectively. Despite these differences, the values obtained are relatively high and could be considered as sufficient to control T. evansi populations efficiently (Gerson et al. 2003), even if more information about the specific predator/prey relation between P. longipes and T. evansi are needed to prove P. longipes effectiveness at a field scale (Janssen and Sabelis 1992).

The temperature for optimum development and reproduction of T. evansi was estimated to be 34°C (r m ≈ 0.4) (Bonato 1999). The optimum for P. longipes could not be determined in this study, but seems to occur at more than 30°C. It could thus be stressed that P. longipes would reproduce well at a wide range of temperatures in presence of T. evansi. It seems to perform better in warm environments, at temperatures at which T. evansi also develops better.

Furtado et al. (2006a, submitted) worked for the first time on the Brazilian P. longipes strain biology. Three major differences can be found between their study and the results reported here. Firstly, the adult phases are always longer in their work than in the present. Then, the secondary sex ratio is also higher, 0.90 vs. 0.78 between Furtado et al. (2006a, submitted) and the present values, respectively. Finally, all the reproductive parameters are greater, due to a major difference in the daily oviposition rates obtained in this previous study. Those differences could be explained mainly by two reasons. In Furtado et al. (2006a, submitted), the P. longipes stock colony was reared on tomato and fed on T. evansi. In the present paper, it was reared on C. ensiformis and fed T. urticae for many generations before the tests. The second point is that biology tests were performed in this paper on S. americanum instead of L. esculentum in the other work. Despite these differences, both papers reported that the life table parameters values would support the effectiveness of the Brazilian strain of P. longipes for T. evansi biocontrol. These promising results should lead to further work, for instance to compare variations of life table parameters, and especially oviposition, depending on the food provided and the vegetal support on which experiments are conducted.

Phytoseiulus longipes has excellent potential as a biocontrol agent for T. evansi, in European tomato greenhouses as well as in small-scale tomato production in Africa. The temperatures at which it develops and reproduces well lead to promising perspectives for its use in solanaceous greenhouses. Further experiments on its effectiveness and uses in biocontrol will be conducted in order to set the right conditions in which P. longipes would be the most efficient.

References

Aucejo S, Foo M, Gimeno E, Gomez A, Monfort R, Obiol F, Prades E, Ramis M, Ripolles JL, Tirado V (2003) Management of Tetranychus urticae in citrus in Spain: acarofauna associated to weeds. IOBC/WPRS Bull 26:213–220

Badii MH (1981) Experiments on the dynamics of predation of Phytoseiulus longipes on the prey Tetranychus pacificus (Acarina: Phytoseiidae, Tetranychidae). University of California, Riverside. PhD Thesis. 153 p

Badii MH, McMurtry JA (1983) Effect of different foods on development, reproduction and survival of Phytoseiulus longipes (Acarina: Phytoseiidae). Entomophaga 28(2):161–166

Birch LC (1948) The intrinsic rate of natural increase of an insect population. J Anim Ecol 17:15–26

Blair BW (1989) Laboratory screening of acaricides against Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard. Crop Prot 8:212–216

Bolland HR, Gutierrez J, Flechtmann CHW (1998) World catalogue of the spider mite family (Acari: Tetranychidae). Brill, Leiden, 392 p

Bolland HR, Vala F (2000) First record of the spider mite Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae) from Portugal. Entomol Berichten 60(9):180

Bonato O (1999) The effect of temperature on life history parameters of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp Appl Acarol 23:11–19

Castagnoli M, Nannelli R, Simoni S (2006) Un nuovo temibile fitofago per la fauna italiana: Tetranychus evansi (Baker e Pritchard) (Acari: Tetranychidae). Inf Fitopatol 5:50–52 (in Italian)

Escudero LA, Ferragut F (2005) Life-history of predatory mites Neoseiulus californicus and Phytoseiulus persimilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae) on four spider mite species as prey, with special reference to Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Tetranychidae). Biol Control 32:378–384

Ferragut F, Escudero LA (1999) Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari: Tetranychidae), una nueva araña roja en los cultivos hortícolas españoles. Bol San Veg Plagas 25(2):157–164 (in Spanish)

Furtado IP (2006) Sélection d’ennemis naturels pour la lutte biologique contre Tetranychus evansi Baker & Pritchard (Acari: Tetranychidae) en Afrique. Agro-Montpellier, France. PhD thesis, 135 p (in French)

Furtado IP, Moraes GJ de, Kreiter S, Tixier M-S, Knapp M (2006a) Potential of a Brazilian population of the predatory mite Phytoseiulus longipes as a biological control agent of Tetranychus evansi (Acari: Phytoseiidae, Tetranychidae). Biol Control, submitted

Furtado IP, Moraes GJ de, Kreiter S, Knapp M (2006b) Search for effective natural enemies of Tetranychus evansi in south and southeast Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol 40(3–4):157–174

Gerson U, Smiley RL, Ochoa R (2003) Mites (Acari) for pest control. Blackwell Science, Oxford (UK), 539 p

Gotoh T, Yamaguchi K, Mori K (2004) Effect on life history of the predatory mite Amblyseius (Neoseiulus) californicus (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Exp Appl Acarol 32(1–2):15–30

Janssen A, Sabelis MW (1992) Phytoseiid life histories, local predator-prey dynamics, and strategies for control of tetranychid mites. Exp Appl Acarol 14:233–250

Ma W-L, Laing JE (1973) Biology, potential for increase and prey consumption of Amblyseius Chilenensis (Dosse) (Acarina: Phytoseiidae). Entomophaga 18(1):47–60

Maia A, Luiz AJB, Campanhola C (2000) Statistical inference on associated fertility life table parameters using Jackknife technique: computational aspects. J Econ Entomol 93(2):511–518

McMurtry JA, Croft BA (1997) Life-styles of phytoseiid mites and their roles in biological control. Ann Rev Entomol 42:291–321

Migeon A (2005) Un nouvel acarien ravageur en France: Tetranychus evansi Baker et Pritchard. Phytoma 579: 38–43 (in French)

Moraes GJ de, McMurtry JA (1985) Comparison of Tetranychus evansi and Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) as prey for eight species of phytoseiid mites. Entomophaga 30(4):393–397

Moraes GJ de, McMurtry JA (1986) Suitability of the spider mite Tetranychus evansi as prey for Phytoseiulus persimilis. Entomol Exp Appl 40:109–115

Moraes GJ de, McMurtry JA (1987) Effect of temperature and sperm supply on the reproductive potential of Tetranychus evansi. Exp Appl Acarol 3:95–107

Moraes GJ de, Mcmurtry JA, Denmark HA, Campos CB (2004) A revised catalog of the mite family Phytoseiidae. Zootaxa 434. Magnolia Press. Auckland, New Zealand, 494 p

R project (2006) The R manuals. Edited by the R Development Core Team. Current Version: 2.4.0 (October 2006). http://www.r-project.org

Sabelis MW (1985) Capacity for population increase. In: Spider mites, Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control, vol 1B: 35–41. Helle W. & Sabelis M.W., Elsevier, Amsterdam

Saunyama GM., Knapp M (2003) Effect of pruning and trellising of tomatoes on red spider mite incidence and crop yield in Zimbabwe. Afr Crop Sci J 11(4):269–277

Takahashi F, Chant DA (1992) Adaptative strategies in the genus Phytoseiulus Evans (Acari: Phytoseiidae). I. Developmental times. Int J Acarol 18(3):171–176

Takahashi F, Chant DA (1994) Adaptative strategies in the genus Phytoseiulus Evans (Acari: Phytoseiidae). II. Survivorship and reproduction. Int J Acarol 20(2):87–97

Zhang Z-Q (2003) Mites of greenhouses, Identification, Biology and Control. CABI, London, 244 p

Acknowledgements

This collaborative research between the Red Spider Mite Project at ICIPE, ESALQ/USP and ENSAM/INRA was funded by a grant of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) to ICIPE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrero, M., de Moraes, G.J., Kreiter, S. et al. Life tables of the predatory mite Phytoseiulus longipes feeding on Tetranychus evansi at four temperatures (Acari: Phytoseiidae, Tetranychidae). Exp Appl Acarol 41, 45–53 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9053-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9053-6