Abstract

We analyze favors as utilization of informal modes of exchange within a formal economy, relating their negative aspects to corruption. This exercise enables us to integrate them into a model linking national institutional factors to the magnitude of cross-country FDI flows. In our empirical tests of FDI inflows in 55 countries across four distinct time periods, we find that the level of economic regulation is a major determinant of the extent of FDI inflows as well as the level of corruption, but corruption does not have an independent influence on levels of FDI inflows. Our results have important policy implications regarding the role of the state in influencing the location decisions of MNEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

One way of conceiving favors is to think of them as the pervasive utilization of informal modes of exchange within the formal sector (Lomnitz, 1988). These exchanges vary according to the extent of reciprocity expected by the parties involved. Favors are often seen as a necessary part of business activities, especially in emerging market economies (Myrdal, 1970). Favors can be positive or negative elements of the business environment. On the one hand, favors can facilitate extant business transactions or trigger ones that would not otherwise occur. On the other hand, they can lead to inefficient outcomes, since decisions may not be made based on the underlying capabilities of market participants. This negative aspect is the subject of this paper.

We concentrate our attention on those informal exchanges that involve public decision makers. Therefore, the formal system is the public sector and the decision makers are public bureaucrats. From a transaction costs perspective, firms might implement informal exchanges as a means of circumventing the expensive regulatory burden and/or pursuing governmental support (Husted, 1994). In this context, favors may be defined more specifically as the occurrence of at least two transactions, with the roles of service supplier and receiver being reversed in sequential transactions, and with reciprocity that can be delayed and indirect (Verbeke & Greidanus, 2009; Verbeke & Kano, 2013). In this sense, favors consist of various forms of trading influence and bureaucratic favoritisms for equivalent services or cash. These situations arise whenever decisions are made by bureaucrats, who are not guided by market-based metrics (Niskanen, 1968). To put it more generally, informal exchanges take place to obtain preferential treatment from bureaucrats in response to the inadequacies of the formal mechanisms of decision making.

Informal exchanges may take the form of either legal or illegal practices. In the first case, we think of interpersonal connections embedded and exploited on business activities that promote mutual benefit within the bounds of the law. These connections are reciprocal practices exploited by different individuals to secure bureaucratic favoritism in obtaining certificates, transcripts of documents, permits, tax clearances, and countless other items, including social introductions to people who can eventually procure these favors. In the second case, illegal informal exchanges involve the misuse of public power for private benefit, through unauthorized payments of money or other in-kind substitutes. Such material payments in return for favors performed by public officials take the form of bribes and are generally not associated with personal relationships.

It is important to note that the boundary between legal and illegal informal exchanges is often a matter of social norms. Societal tolerance toward strong interpersonal involvements is higher in relational cultures and this can lead to practices of bureaucratic favoritism (Husted, 1999; Luo, 2002; Myrdal, 1970).

In this paper the type of favors we focus on are illegal informal exchanges that are commonly known as corrupt practices. More specifically, we are interested in examining the effect of corruption on the location decision of foreign direct investment (FDI) by multinational enterprises (MNEs). We argue that the more the economic system is regulated and planned the greater the scope for informal modes of exchange through illegal shortcuts. Corruption thrives on the inefficiencies of the regulatory system and tends to perpetuate itself through the temptations for personal gain that are presented to the relevant bureaucrats. We develop a systematic theory examining the effect of regulation on corruption, that has important implication for cross-country FDI flows.

Research in international business devotes considerable conceptual and empirical effort to identifying the determinants of cross-border FDI flows (Dunning, 1993). This rather large literature has uncovered a number of host country institutional factors (political, social, and economic) that are related to firm performance and FDI inflows (Cuervo-Cazurra & Dau, 2009). This literature has largely documented—both theoretically and empirically—that the burden of regulation (Bengoa & Sanchez-Robles, 2003) and corruption (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008; Habib & Zurawicki, 2002; Wei, 2000) affect the location decisions of MNEs. The impact of these two institutional factors on FDI has been analyzed in separate but parallel research paths, without any systematic effort to conceptually link these factors. In this study, we develop a coherent theory that describes the mechanisms by which economic regulation and corruption are related to each other, and how these inter-relationships affect FDI inflows.

By adopting this integrated approach, we are able to demonstrate that much of the existing literature suffers from the causal fallacy of joint effects. In the literature, FDI is held to be independently determined by corruption (Habib & Zurawicki, 2002; Voyer & Beamish, 2004), when in fact both FDI and corruption are each caused by the burden of government regulation (Rose-Ackermam, 1999; Shleifer & Vishny, 1999).

Aside from this objective of conceptualizing and testing an integrated approach, our motivation for this study extends from two conclusions being drawn from these distinct streams of research. First, there is reasonable evidence to conclude that corruption is related to a nation’s institutional features (Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 2002). As excessive regulation is a contributor to corruption, deregulation and privatization can be effective measures to fight corruption, to increase competition in an economy, and to lower the level of opportunistic behavior of state officials (Bliss & Di Tella, 1997; Rose-Ackermam, 1988). Second, corruption in an economy can be seen as a rational response to a given institutional environment. Although research has begun to recognize the important institutional antecedents to corruption activities, research on the relationship between FDI and corruption continues to treat corruption as an exogenous variable unaffected by other social, political, and economic conditions in place in the economies under investigation (Habib & Zurawicki, 2002; Hines, 1995; Smarzynska & Wei, 2002; Wei, 2000).

In this paper, we bridge these ideas, using the focal point of the FDI decision, to examine how the restrictions placed on economic activities and corruption in emerging economies influence the strategies of MNEs. Our approach is novel because we treat corruption as an endogenous feature of a host country environment. Instead of asking the question: What is the influence of corruption on firm strategy and performance?, we ask the more essential question: What factors determine cross-national variances in levels of corruption, and do these same factors influence FDI inflows?

From a managerial standpoint, our work suggests that managers would be well advised to look beyond simple measures of corruption in making their location decisions. In particular, when comparing two locations with relatively similar corruption levels (as often happens in FDI short-listing exercises) (Cantwell & Mudambi, 2000; Mudambi, 1998), managers would be well advised to examine the underlying burden of government regulation. While this is unlikely to be captured in a single summary statistic like a corruption index, it is the basis for making better FDI location decisions.

Our empirical work is based on a sample of 55 countries, with four panels of FDI data drawn from the 1985–2000 time period (1985–86, 1990–91, 1995–96, and 1999–2000). We find that when modeled conventionally, a nation’s corruption levels are inversely related to FDI flows. When we place corruption as an endogenous feature of a host country environment, in a simultaneous equations model, we find that the economic impact of corruption on FDI inflows declines quite substantially, as compared to a treatment of corruption as an exogenous feature of an institutional environment. Meanwhile, the level of economic regulation emerges as a substantive predictor of corruption levels and FDI inflows.

This paper is structured as follows. Next, we review the two theories of government regulation. Then, we develop our theoretical hypotheses. In the Methods, we describe the data and our empirical strategy and carry out the estimation. Then, we discuss our findings and, finally, we present some concluding remarks.

Background

One of the recent focal areas of transition in economic policies in many nations worldwide has been towards a decreased burden of government regulation. A declining burden of regulation decentralizes economic decision making from government-owned to privately-owned enterprises and from highly-regulated to deregulated private enterprises. Accordingly, policies aimed at liberalization, deregulation, and privatization are macro-level factors that can sharply reduce opportunities for corruption (Aguilera & Vadera, 2008; Djankov et al., 2002). In economies with extensive state regulation, greater opportunities for venality exist. The supply of rents for officials to allocate will be higher than in more liberal settings.

The burden of government regulation can also be connected to the extent of corruption in an economy, via either the public interest view or public choice theory. The first approach sees regulation as a remedy for market failures. In this perspective, benevolent government intervention may alleviate the inefficiencies arising from monopoly power and externalities. The second approach questions the very existence of benevolent government. In this view, regulation is essentially a redistributive process among self-interested individuals and/or groups that aim to obtain specific benefits by the means of governmental intervention. The two approaches, therefore, differ in terms of who gets the benefits of regulation.

The public interest view of public policy emphasizes the point that unregulated markets exhibit frequent failures that can be corrected by government regulation (Maidment & Eldridge, 1999; Pigou, 1947). The public interest view (Pigou, 1947) identifies economic regulation as a response to market failures ranging from monopoly power to externalities. Economic regulation overcomes the inefficiencies of these failures through benevolent governmental intervention. Scholars have criticized this approach as unrealistic and have questioned the appropriateness of assuming a government composed of selfless public servants (Stigler, 1971). Critics argue that regulation is a redistributive process influenced by self-interested individuals who attempt to gain specific benefits by the means of government intervention.

In line with this criticism, public choice theory considers governments to be less than benign, and regulation as socially inefficient (Buchanan & Tullock, 1962). If there is less competition in an economy, firms can enjoy higher rents and bureaucrats with high control rights over industries (such as tax inspectors or industry regulators) have greater incentives to engage in malfeasant behavior (Bliss & Di Tella, 1997). Consistent with this line of argument, Ades and Di Tella (1997, 1999) found that corruption is higher in countries where domestic firms are sheltered from foreign competition by natural or policy-induced barriers to trade. Similarly, public sector corruption tends to be more prevalent in economies dominated by small numbers of firms with low levels of product market competition and where antitrust regulations are not effective in preventing anticompetitive practices. The inverse of this is the point that increased competition in an economy discourages corrupt activities and promotes economic growth. Well-established market institutions, characterized by clear and transparent rules, fully functioning checks and balances, and a robust competitive environment reduce incentives for corruption.

In a study of the regulatory burden faced by entrepreneurs seeking to establish start-up firms in 85 countries, Djankov et al. (2002: 26) reported that “…corruption levels and the intensity of entry regulation are positively correlated.” This suggests that the principal beneficiaries of the regulatory burden imposed on start-up businesses are politicians and bureaucrats. Endemic corruption does not suggest a presence or absence of self-interested behavior, but rather a failure to tap self-interest for productive purposes (Rose-Ackerman, 1999).

Corruption in an economy can also extend from another aspect of the regulatory environment, namely where firms face legal obstacles to enter an industry or operate a business. Politicians use their temporary monopoly rights to distort economic policy to generate large rents for themselves (Bardhan, 1997). These activities are most prominent when there is low electoral accountability (Coate & Morris, 1999). Corruption, hence, extends from an underlying weakness of the state to control its bureaucrats, to protect property and contract rights, and to provide institutions that underpin an effective rule of law. Whether these same features of the political environment influence the level of regulation, and thereby make corruption an endogenous feature of a national institutional environment, with respect to its influence on FDI flows is the focus of our hypotheses.

Hypotheses development

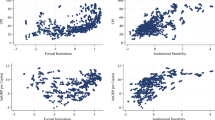

Our study connects two distinct bodies of literature: (1) economic regulation and corruption and (2) market liberalization (the burden of government regulation) and FDI. We integrate ideas from these literatures to show how corruption has been considered to be an exogenous influence on FDI, yet it is fundamentally an endogenous feature of a nation’s business environment. In Figure 1, we graphically depict our contention that the regulatory burden of the state in an economy affects both levels of corruption and of FDI.

Government regulation and corruption

Much of the existing literature points to the regulatory state as being a source of corruption (Bardhan, 1997). The burden of regulation with its elaborate system of permits and licenses spawns corruption (Rose-Ackermam, 1999) and, therefore, different countries with different degrees to which the regulatory state is inserted into the economy give rise to varying levels of corruption (Shleifer & Vishny, 1999). Regulations and bureaucratic allocation of scarce public resources breed corruption, and so the immediate task is to get rid of them. In some sense the simplest and the most radical way of eliminating corruption is to legalize the activity that was formerly prohibited or controlled (Bardhan, 1997). When Hong Kong legalized off-track betting, police corruption fell significantly, and as Singapore allowed more imported products duty free, corruption in customs went down (Klitgaard, 1988).

Tanzi (1998) identified that corrupt activities take place more often in environments where laws and procedures are opaque, which creates a situation in which administrators enjoy substantial discretionary power. The more the rules (the greater the burden of the regulation), the more confusing the system and the more opaque it becomes. In this framework, the more the rules, the greater the chances that they contrast with each other, the less likely they can be effectively enforced and the greater the chances of corruption. As noted by Shleifer and Vishny (1993), regulations provide opportunities for politicians and government officials to engage in corrupt activities, for example, the extortion of payments from private businesses and citizens in exchange for licenses. Where regulation is extensive, we expect that the pervasiveness of corruption is greater.

This point is supported by the large literature on the tollbooth view of regulation, in which a strong regulatory environment creates sufficient conditions for public sector employees to extract benefits for the provision of services governed by regulations (De Soto, 1990; Djankov et al., 2002). Even though the regulatory state can create opportunities for corruption, the extent to which actors engage in corruption will depend to an extent on individual cost-benefit calculations. In a situation in which a public sector official has a low income, corrupt practices will yield a high benefit in relation to the level of risk (Aguilera & Vadera, 2008). As incomes rise, however, the benefits derived from corrupt practices will be less attractive relative to the risks. This form of calculation suggests that corruption should be less prevalent richer societies, as found by Husted (1999). That said, given appropriate consideration for the general administrative tendencies in a nation to the pursuit of public interest, an increased burden of regulation in a nation should lead to a greater level of corruption. All other things being equal, we hence expect to find a higher level of corruption to be associated with a higher level of government regulation.

Hypothesis 1

The lower the level of government regulation, the lower the prevalence of corruption in the economy.

Corruption and FDI

Corruption can be defined as the abuse of public power for private benefit (Tanzi, 1998), in which there is a transfer from private firms or individuals to government officials or politicians, in exchange for preferential treatment in a regulated environment. The mainstream literature on the effects of corruption on FDI almost uniformly argues that corruption negatively influences levels of FDI inflows (Habib & Zurawicki, 2002; Wei, 2000). The argument begins with the point that MNEs often encounter corruption in their FDI, particularly when they enter emerging market economies (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2008; Smarzynska & Wei, 2000). Corruption deters investment because it increases the direct costs and uncertainty of doing business. Further, in most nations, corruption is illegal. The consequent requirement for secrecy for business undertaken with corruption is risky since investors have limited protection from expropriation (Shleifer & Vishny, 1993).

The pervasiveness of corruption is a probabilistic measure and refers to the likelihood that an entering firm will encounter corruption in its dealings with government officials or politicians in the host country (Rodriguez, Uhlenbruck, & Eden, 2005). A high level of pervasiveness indicates that firms are more likely to encounter corruption when undertaking normal business activities.

As with other dimensions of the political environment (Henisz & Delios, 2004), MNEs can cope with corruption by either avoiding locations where they encounter it, as marked by the pervasiveness of corruption, or by adjusting their entry modes to reduce their exposure (Doh, Rodriguez, Uhlenbruck, Collins, & Eden, 2003). If corruption is pervasive, MNEs are more likely to choose no entry, or an arm’s-length entry strategy, such as exporting or licensing. Hence, corruption can impose a cost on MNEs that leads to a negative effect of corruption on FDI inflows (Habib & Zurawicki, 2002; Wei, 2000). Accordingly, we expect that when modeled independently of other features of the national institutional environment, the pervasiveness of corruption should be negatively associated with levels of FDI inflows.

Hypothesis 2

The greater is the pervasiveness of corruption in the host country, the lower the level of FDI inflows.

Government regulation, corruption, and FDI

We connect the ideas in our first two hypotheses with our view that corruption can be considered as an endogenously determined feature of a nation’s business environment. Further, as we contend in H1, corruption levels can be connected to the burden of government regulation.

Even with a general worldwide trend in the 1990s and 2000s towards lower levels of government regulation, it is still present in all economies and yet pervasive in others. Economic regulation is one of the policy decisions that matters the most for the functioning of an economy. It concerns the extent of state intervention in the market economy and the degree of discretionary power allocated implicitly or explicitly to bureaucrats. A major impetus in the trend towards decreased levels of government regulations has been its connection to economic outcomes, such as the intensity of foreign participation in an economy.

A small but focused literature calls attention to the effect of the burden of regulation on FDI (Bengoa & Sanchez-Robles, 2003). With respect to the FDI decision, corporate tax rates, as one area of regulation, have been found to be an important factor in explaining location decisions by MNEs (Wheeler & Mody, 1992). Within a single country, tax incentives can influence the location choice of a firm’s investment (Tung & Cho, 2001). Bengoa and Sanchez-Robles (2003) found economic freedom and economic growth to be positively correlated with FDI inflows into Latin American countries. Latin American countries with high levels of political stability, together with a deregulated environment, tend to attract high levels of inward FDI.

This emerging literature points to the existence of a relationship between the burden of government regulation and FDI, just as the literature has documented a link between corruption and FDI. We posit that these relationships are two sides of the same coin. Specifically, we suggest that the literature on corruption focuses excessively on legal status. For example, Shleifer and Vishny (1993) argued that corruption imposes a greater burden on the economy than taxation because of the secrecy that is necessarily associated with an illegal activity. We do not dispute this point. Taxes reduce welfare by distorting resource allocation, but they can also have positive welfare effects, for example, in terms of the provision of public goods. Corruption, on the other hand, imposes an asymmetric cost on an economy. It provides a public sector official with a gain, but it does so by imposing a cost on a firm, that can deter private sector activity, such as FDI.

These arguments suggest that the level of government regulation has both a direct and indirect effect on FDI. The direct effect works through lowering the legal expenses of complying with regulatory procedures and red tape. The indirect effect works through the hypothesized (H1) negative relationship between the burden of government regulation and corruption. As regulations are removed, the scope for corrupt activities shrinks, reducing the costs of operating in the host country. Hence:

Hypothesis 3

The lower the burden of government regulation, the higher the level of FDI inflows into the host economy.

Although we cannot form a hypothesis about a null effect, our previous arguments also suggest that corruption should have a decreased, or at the extreme, no influence on FDI levels, when it is considered to be an endogenous feature of the environment, or a consequence of the level of government regulation in an economy (H1). An argument for a null effect of corruption on FDI inflows is consistent with existing empirical work, which does not find a link between the extent of corruption and the level of FDI inflows (Hines, 1995; Wheeler & Mody, 1992). We have predicted in H3 that FDI levels respond directly to levels of government regulation. Continuing the argument along these lines, we expect that FDI should not be related to levels of corruption, once we account for the state of the regulatory environment. We examine this alternative outcome to H2 (i.e., corruption is not related to FDI inflows) in the models we construct to test our hypotheses.

Regulation enforcement and corruption in developing countries

In Figure 1 we describe a situation in which the more the economic system is regulated and planned, the greater the scope for informal modes of exchange through illegal shortcuts. A more careful examination of the figure, might lead a reader to ask whether there is any role played by the enforcement of regulation in determining its effects on corruption. Although to the best of our knowledge there are no data that measure the effectiveness of the judiciary and regulators in the fight against corruption for the countries and the time span under investigation in this study, it is interesting to comment on some findings obtained in the literature examining the relationship between the extent of government regulation and the enforcement capabilities of the judiciary in developing countries.

Starting with Becker (1968) and Stigler (1970), a line of research investigated the optimal enforcement of laws (see Polinsky & Shavell 2000; Shavell 1993). One important result in this literature is that stricter and more complex laws and regulations require more incisive and costly enforcement machinery (Holmes & Cass, 1999). This result has important implications for less developed countries. Although good laws and rules are rather simple to import from the developed to the developing world, their enforcement is much more difficult because of the lack of financial and technical resources and because of the weak bargaining position of regulators (Ordover, Pittman, & Clyde, 1994). Therefore, less developed countries suffer from significant weaknesses of enforcement capabilities (Laffont, 1996). This implies that regulations in developing and emerging economies tend to be either loose and effective or strict and ineffective. In both cases there is large scope for corruption. Loose regulations are more likely to be overturned by illegal actions and behaviors. On the other hand, strict regulations are associated to weak and often fruitless enforcement and, as a consequence, are more likely to open the way for the enactment of corrupt practices.

Methods

Sample

We develop our sample using country-level data drawn from several published and electronic sources. We provide complete details on sampled countries, and a description of the data and the data sources in the Appendix. The sample we constructed for the analysis is panel data that has cross-national variance across 55 countries. The within-country variance comes from the four panels of data (1985–86, 1990–91, 1995–96, and 1999–2000) we have to cover the period from 1986 to 2000, which is a comparatively long period for corruption-FDI related research. In line with the panel nature of our data, our variables are time-varying, with the exception of the indicator variables which will not change over time. By using time periods, rather than annual observations in our sample, we provide opportunity for institutional variables to change over time, even given the point that the rate of institutional change can be slow. In these ways, our sample is primarily cross-sectional, but it does provide multiple period snapshots of each of the 55 countries in our sample.

Measures

Endogenous variables

Our two endogenous variables (Figure 1) are (1) the extent of corruption and (2) the level of FDI inflows.

We measure the level of corruption with the widely-used survey-based measure created by Transparency International (Husted, 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2005; Wei, 2000). The formal Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) began to be reported in 1995, which are the data we used for the 1995 and 2000 panels. The Transparency International CPI evolved out of a precursor index developed at the Internet Center for Corruption Research, University of Passau, Germany (Lambsdorff, 1999), which was constructed using the same methodology as the CPI. The precursor index is available for the 1980–85 and 1988–92 periods, in two snapshots anchored in the years 1985 and 1990. The range of country coverage for the precursor index is less than the CPI, hence resulting in our sample being limited to 55 countries. For the Transparency International measure, high values mark low levels of corruption.

It is important to note that several other corruption measures are available in the literature. Among them, one of the most used indicators of corruption is the one offered by International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) compiled by the political Risk Service Group. However, our choice of the CPI for measuring corruption is determined by the fact that it is the only one that covers all the countries considered in the empirical analysis for the time span under investigation in our study.

We measure the level of inward FDI inflows by the average annual value in US dollars of FDI into a given country for each panel. We used the log form of this variable after testing for normality using the standard Jarque-Bera test. The value of the test statistic [chi-square(2)] was marginally significant, suggesting that the use of the log form is not essential, but a useful precaution. We note here that both the logged and (mean-centered) unlogged FDI flow measures yield very similar results in our models, indicating that normality is not a significant concern. We implement models using the logged form because it reduces leverage issues associated with outliers, yielding superior estimates to those from the unlogged form.

Exogenous variables

The three variables used to test our hypotheses are the two endogenous variables, plus a measure of the extent of government regulation. To operationalize the burden of government regulation we use the economic freedom index generated by the Fraser Institute (Doucouliagos & Ulubasoglu, 2006; Dreher & Rupprecht, 2007). There are a number of measures of economic freedom, but the Fraser Institute data is our preferred measure for a number of reasons. It is the only economic freedom measure that covers our intended wide time span. The Heritage Foundation index is not available before 1995, while the economic freedom indices generated by the World Bank are only available from 2000 onwards. Further, in a recent survey, De Haan, Lundstrom, and Sturm (2006) compared several indices of economic freedom including the Fraser Institute and the Heritage Foundation indices. Their survey concludes that the Fraser Institute index is the best at capturing the essence of market-oriented economic institutions. Finally, we note that the correlation between the Fraser Institute and the Heritage Foundation indices is reasonable at a level .85 (Cumings, 1984).

To complete our specification of exogenous variables in our models, we turned to the literature to identify variables that determine each of the two endogenous variables. Both corruption and FDI are likely to be sensitive to a number of other environmental influences. Hence we control for socio-economic (Cheng & Kwan, 2000; Smarzynska & Wei, 2002; Wei, 2000) and institutional factors (Adam & Filippaios, 2007; Bengoa & Sanchez-Robles, 2003; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 2008, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 2008). We control for the level of GDP (income and the extent of the market) and the growth rate of GDP (income and market growth), country risk and inflation (macroeconomic stability), trade exposure and export diversity (open economy measures), literacy rate (human capital and demand sophistication) and the level of civil liberties and the legal heritage of the country (civic and legal institutions).

The model

In Table 1, we present summary statistics and a correlation matrix for all variables used in this study. As can be seen in the table, inter-item correlations are modest to low, but still at a level where we needed to institute checks to see if estimated coefficients were affected by collinearity concerns. Aside from our examination of the correlation matrix, we tried various specifications that included or excluded variables that were moderately correlated with one another. When doing this, we checked for the stability of coefficient estimates across specifications and we looked for large changes in standard errors, both of which are symptomatic of collinearity. We did not observe any instability in estimates, enhancing the confidence with which we could interpret the estimated coefficients as not being the product of collinearity. Finally, for all specifications and variables, we estimated VIFs, with all VIFS well below the threshold value of 10.

Our hypotheses predict a series of relationships in stages, for which a common method to use is structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM is particularly useful for modeling exogenous and endogenous variables, but it has its greatest utility when constructs have multiple items. All variables in our analysis are single-item measures, so we use a simultaneous equations approach (two-stage least squares, or 2SLS) instead of SEM.

The simultaneous equation system we use consists of two equations:

where C1 and C2 are the vectors of control variables, as identified in the preceding section. This model builds from the idea that estimating the effects of economic institutions on FDI requires a simultaneous equations approach in which levels of corruption (Eq. 1) are predicted by burden of government regulation. Equation 2 predicts FDI levels from government regulation, corruption, and the control variables.

As one of the main points of investigation in our study is to identify whether corruption, and its influence on FDI inflows, is endogenously determined, we first establish an empirical benchmark by estimating a set of single equations of the variables on FDI inflows, following Habib and Zurawicki (2002) and Harms and Ursprung (2002). This benchmark establishes the point that our results for the effects of corruption on FDI in the 2SLS estimation are not a consequence of poor variable definitions nor of sample selection bias. Instead, the effect of corruption on FDI emerges as a consequence of how we have modelled corruption as an endogenous variable in the 2SLS estimation.

The estimation

We estimate FDI inflows two ways. First, we generate estimates akin to those that appear in the corruption-FDI literature. These involve using ordinary least squares (OLS) to estimate Eq. 2, treating corruption as an exogenous variable. We wish to demonstrate that we are able to reproduce the effects of corruption on FDI in our sample.

Second, we estimate Eq. 2 using 2SLS, treating corruption as an endogenous determinant of FDI. 2SLS is a robust and consistent estimation methodology, although it is not unbiased (Greene, 1997). However, it is well-known that the quality of 2SLS results is crucially dependent on the validity and quality of instruments used. A strong instrument is correlated with the endogenous regressor for reasons the researcher can verify and explain, but uncorrelated with the outcome variable beyond its effect on the endogenous regressor (Bowden & Turkington, 1984). Further, with one endogenous regressor, it is necessary to have at least three over-identifying restrictions to extract a consistent estimate along with its standard error (Kinal, 1980). We ensure that this requirement is met.

We use inflation, the level of civil liberties, export diversity, and legal heritage as our main instruments. These variables were identified on the basis of the prior literature as being correlated with corruption but not with FDI, indicating their suitability as potential instruments. Corruption has been associated with inflation rates (Paldam, 2002), the level of civil liberties (Lambsdorff, 2003), the extent of trade openness (Knack & Azfar, 2003), and legal institutions and heritage (Fisman & Gatti, 2006).

We now examine the relationship between each one of these potential instruments and FDI. FDI is based on foreign inputs and/or markets, so that it may remain relatively insulated from domestic inflation, a position that has found empirical support (Trevino, Daniels, Arbelaez, & Upadhyaya, 2002). Further, foreign firms are essentially profit maximizing entities and it is unclear why the state of domestic civil liberties should have a systematic effect on FDI. The empirical evidence with regard to this relationship is mixed (e.g., Jakobsen & de Soysa, 2006; Li & Resnick, 2003). Direct measures of trade openness like the level of exports have a clear theoretical relationship with FDI and are unsuitable as instruments. However, the diversity of exports relates to openness, but has no systematic link to the level of FDI, that is, a country may have a high level of FDI either from a single dominant sector or from general openness leading to inflows into a wide range of sectors. Thus, greater export diversity relates to trade openness, but need be correlated with FDI.

Our above discussion is borne out by the data. With the exception of legal heritage, all instruments are highly correlated with the level of corruption, but not with the level of FDI inflows. Finally, previous research has identified Africa as a region with a significantly different corruption profile compared to other geographical regions (Heineman & Heimann, 2006). Therefore, in our estimation of corruption we include an instrument to control for this effect.

Results

As mentioned above, prior studies of FDI flows have focused on estimating a single equation (like Eq. 2). We first estimate Eq. 2 alone to ensure that we can reproduce the results reported in the corruption-FDI literature using our data. We use a panel data approach and present the estimates in Table 2. These estimates demonstrate that we are able to reproduce the negative effect of corruption on FDI that is reported in much of recent literature. In other words, a higher level of corruption (a lower value of the corruption index) is associated with lower levels of FDI inflows.

Having reproduced the findings of the literature in this area, we proceed to examine the effect of treating corruption as an endogenous variable. The panel estimates of Eq. 2 are presented in Table 3. We estimate Eq. 2 using an instrumental variables (IV) methodology, with corruption as an endogenous regressor. The results of this estimation are presented in Table 4. We also reproduce the estimates of Eq. 2 alone in the second column of Table 4 for purposes of comparison.

Two aspects of the regulatory burden appear to be associated with corruption (Table 3): the legal structure of private property rights protection and the freedom to trade internationally. The lower the security afforded to private property through the legal system, the greater the incentive to obtain protection through alternative means. These are likely to involve corrupt practices. For instance, it has been documented that the greater the extent of tariffs and other restrictions on the availability of desirable foreign products, the greater the extent of practices like smuggling that often involve corruption (Gillespie & McBride, 1996). This applies with even more force in the international context, where the illegality of drugs has created extra-legal corporations that fund corruption on an international scale (Mudambi & Paul, 2003). Further, in many African countries, police forces often extract protection payments or bribes and provide security for life and property only to those who pay, rather than to the public at large (Rose-Ackermam, 1999).

Several of the control variables are significant in the direction expected in estimating the extent of corruption. Higher incomes, more trade-exposed economies with greater export diversity, higher literacy, and higher levels of civil liberties are all associated with lower levels of corruption. As noted by Shleifer and Vishny (1993), the illegality of corruption means that it requires secrecy. This means that open societies with high levels of civil liberties are less likely to be conducive to such behaviors.

The geographic dummy identifying African countries appears to be associated with lower levels of corruption. Although this result may appear surprising, the positive effect of the Africa dummy on corruption may be interpreted as follows. The African economies in our sample have among the lowest incomes and highest regulatory burdens. The expected levels of corruption are therefore extremely high—higher in fact than the index is able to capture since it is bounded below by zero. Further, the multiple-survey-based nature of the Transparency International CPI means that even very low reported scores tend to be positive. Since the expected values of the index for many African economies are negative, while the actual values are all positive, the coefficient of the dummy takes a significant positive value.

We now proceed to examine the estimates of FDI flows presented in Table 4. The two main explanatory variables are the extent of the regulatory burden and the endogenous level of corruption. The aspect of the regulatory burden that is a significant determinant of FDI flows is the size of the government as measured by extent of public expenditure, public enterprises, and taxes. This is consistent with several studies that point to taxes as the most important factor influencing MNE location decisions (Mutti & Grubert, 2004; Wheeler & Mody, 1992).

Most importantly, we emphasize that whether we treat the level of corruption as exogenous or endogenous changes its estimated effect on FDI. As noted above, when the level of corruption is treated as exogenous, it appears to exert a significant negative influence on FDI (see column 2 in Table 4). However, when it is treated as endogenous, its relationship with FDI is no longer statistically significant (see column 3 in Table 4). Further, the significance of the effect of the regulatory burden on FDI flows is increased when the endogeneity of corruption levels is taken into account.

Why is the regulatory burden associated with tariffs and trade not significant in determining FDI? This is because the measure examines the costs of undertaking export–import activity. Assuming that most FDI into developing countries is market-seeking and based largely on domestic tangibles and imported intangibles, tariffs would not have strong effects on FDI flows. In fact, as tariffs and other restrictions on trade rise, ceteris paribus, the incentive to undertake tariff-jumping FDI increases (Dehejia & Weichenrieder, 2001). Thus, the negative effects of trade regulation on FDI flows may be counter-balanced by tariff-jumping, so that the overall impact is insignificant.

Finally, we control for standard location attractiveness factors like the size of the market (GDP), the growth rate of the market (the growth rate of GDP), macroeconomic stability (the level of country risk and the inflation rate), openness of the economy (trade percentage) as well as human capital and demand sophistication (adult literacy). Market size and the openness of the economy appear to be the strongest control variables associated with FDI flows.

Discussion

We examine the influence of corruption on FDI levels, by developing arguments about, and constructing an empirical model for, corruption as both a cause and an effect. The starting point for our analysis is our consideration that corruption will vary systematically across countries, according to the nature of a country’s institutional environment. The same features of a national institutional environment that influence levels of corruption can also operate as influences on FDI inflows as they affect managerial behavior (Zhou & Peng, 2013). As such, we constructed a systems model in which we considered FDI and corruption as endogenous variables that are related to other features of national institutional environments, when we tested the determinants of cross-national FDI inflows across 4 panels of data for 55 emerging economies.

In our analysis, we contend that the level of corruption is determined by the burden of government regulation in the economy (Djankov et al., 2002). Hence, the level of corruption is also endogenous. Relatedly, we find FDI inflows to be positively influenced by economic freedom. Our theoretical integration thus indicates that models that treat the level of corruption as an exogenous determinant of FDI inflows are mis-specified, so that their results are questionable (e.g., Habib & Zurawicki, 2002).

These points emerge in our empirical results. When we model corruption in a standard fashion (Table 2), as an exogenous feature of an institutional environment, we find that consistent with much of the extant empirical literature it is negatively related to the extent of FDI inflows. When we consider corruption as an endogenous feature of an institutional environment (Tables 3 and 4), we find that corruption has no relationship to FDI inflows. Instead, the burden of government regulation is the principal determinant of the level of FDI inflows, as well as a determinant of the level of corruption. Hence, once we conceptualize and empirically test the endogeneity of corruption, we find that its net effect over and above that of the regulatory burden (economic freedom) is negligible.

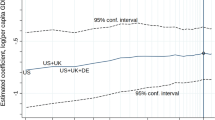

This latter point is evident when we plot the predicted influences of economic freedom and corruption on FDI inflows: As can be seen in Figure 2, moving from a mean level of economic freedom to the highest level of economic freedom increases the predicted level of FDI inflows by a factor of eight. A similar shift in corruption, from its mean level to its lowest level, results in no substantive change in the level of expected FDI inflows. Clearly, the regulatory burden of the state has a much stronger negative impact on FDI inflows than corruption. Corruption appears to be an outcome of the institutional features of a nation, with the consequence that its marginal impact on FDI inflows is negligible.

These findings are important theoretically for three main reasons. First, we contribute to the international business and economics literatures on the determinants of FDI by offering a systematic theory to evaluate the impact of economic institutional factors on FDI. Second, our findings help us to understand the causal links that define the investment climate that influences the magnitude and direction of cross-country FDI flows. Third, our results have important policy implications regarding the role of the state in influencing the location decisions of MNEs.

Related to this third point, our arguments and findings point to the idea that reducing the burden of government regulation can be a powerful stimulus for inward FDI flows. The effect of lower regulation is both direct and indirect. The direct effect spurs FDI through the removal of barriers to entry and exit. The indirect effect works through the positive consequences of the reduced regulatory burden: more transparency, higher levels of competition, and lower returns to public sector corruption. We provide evidence that the direct effect dominates the indirect effect, although the indirect effect can be important.

In a related fashion, our results have important government policy implications. Since corruption affects the investment location decisions of foreign firms, governments might be tempted to implement policy actions to fight corruption to attract FDI. However, this policy choice will likely be limited in its effectiveness if it is not accompanied by a reform in markets and political institutions. This is because corruption and FDI are jointly determined by the extent of regulatory burden. Put another way, corruption is an effect and not a cause.

The perspective we adopt in this study also has value for practitioners. Managers contemplating an investment in potential host country sites will clearly be concerned with the level of corruption in the countries under consideration. Their concern is not just with the present environment, but also with the future environment. By directing attention to the influence of economic regulation on corruption, we can suggest that managers try to identify how government regulation reforms are progressing when forming predictions about future levels of corruption in a nation. Rather than viewing corruption as a static element in a nation, corruption levels can change, particularly in emerging economies where economic institutions are undergoing a relatively rapid evolution.

Recent data supports this contention, especially for Asian countries. Results from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Surveys that cover over 11,000 firms (World Bank, 2011) indicate that the overall trend in emerging market economies is towards a lower burden of administrative regulation as well as a decline in the level of corruption over the period 2005–2010. This is a broad-based trend wherein we witness a reduction in the three major burdens associated with state intervention: taxes, customs, and legal requirements. The data indicate that this trend is particularly pronounced in the East Asia and Pacific groups of countries, which have also witnessed the fastest economic growth in recent years. In fact, the share of the largest Asian economies in global outward FDI flows increased from about 10 % to over 20 % during the same 5-year period. The importance of this relationship is underscored by the fact that FDI constitutes a large and increasing percentage of overall gross fixed capital formation in Asian countries. For example, the figures for Singapore, Cambodia, and Vietnam are 60 %, 52 %, and 25 %, respectively.

These data emphasize the importance of our results. We do not claim that policymakers reduced the burden of regulation with the express purpose of fighting corruption. As our paper demonstrates, supported by the above empirical evidence, liberalization policies, especially in Asia, had two salutary outcomes: one intended and one unintended. The intended consequence was that reductions in the extent of state intervention typically attracted FDI. The unintended consequence was that the extent of corruption declined.

Limitations

In the design of our study, we contend that government regulation is tightly related to levels of corruption. A limitation of our study is that we only consider the existence of regulation as an indicator of the opportunities for corrupt practices. The quality of the rules and regulations is likewise important. The Fraser Institute variable that we use to measure the burden of government regulation is a composite measure that includes both quantitative (number of rules) and qualitative (impact of rules) dimensions. In this way, our measure does capture elements of the existence and quality of rules. However, a finer distinction could be drawn, such as recent work decomposing corruption along the two dimensions of pervasiveness and arbitrariness (Rodriguez et al., 2005): the first dimension relates to how widespread corruption is and the second refers to the uncertainty associated with having to make corruption payments.

An important aspect that might affect the relationship between regulation, corruption, and FDI is the impact of national culture. There is an established strand of research that examines whether and to what extent cultural distance determines the location decision of multinationals, their entry mode and the successes and/or failures of their business operations (Shenkar, 2001). We have not explicitly taken into consideration national cultures in our empirical analysis. Nonetheless, the effect of culture is indirectly picked up in our estimations by the country dummies. Although this can be viewed as a limitation of our research, it opens the scope for future research in which to address how culture might relate to corruption by comparing developing and developed countries.

Finally, we recognize that our data relate to less developed and emerging market economies. We chose such a restricted sample in order to ensure an “apples to apples” comparison. Further, such economies tend to have rapidly changing institutional environments (Kumaraswamy, Mudambi, Saranga, & Tripathy, 2012). This creates many opportunities for the exercise of corrupt practices since such countries “exhibit more institutional flexibility than more developed countries where property rights are well established and defended” (Mudambi, Navarra, & Paul, 2002: 185). Therefore, we would be cautious about extending our results to the case of advanced market economies. However, very poor countries are likely to exhibit similar institutional characteristics with regard to the defense of property rights as the countries in our sample, so we would expect our results to hold there.

Conclusion

There is a substantial empirical literature documenting the negative effect of corruption on FDI (Habib & Zurawicki, 2002; Hines, 1995; Smarzynska & Wei, 2002; Wei, 2000). There is also a literature documenting the linkage between corruption and the extent of the regulatory burden (Ades & Di Tella, 1999, 1997; Djankov et al., 2002; Shleifer & Vishny, 1999). Integrating these findings leads to the implication that an increased burden of regulation leads to both higher levels of corruption and lower levels of FDI.

In this paper, we develop a theoretical model in which the volume of FDI and the level of corruption are jointly determined by the extent of the government regulatory burden. The model integrates the two strands of literature discussed above. In doing so, we are able to develop a choice-theoretic framework explaining the determination of the extent of the regulatory burden. The level of corruption emerges as endogenous outcome of the interaction between MNC firms and the government. Intuitively, governments that have very short time horizons are more likely to choose heavier regulatory burdens since they place less value on future inflows of FDI. In contrast, governments that have longer time horizons choose lighter regulatory systems. Such policies have two self-reinforcing effects. First, they stimulate the development of a larger FDI stock that is a lucrative source of future corruption payments. Second, they enhance the likelihood of government survival through more rapid economic growth and high skill employment through technology transfer and spillovers (Cantwell, 1995).

Estimating FDI using corruption and other standard control variables, we are able to reproduce the results reported in the FDI-corruption literature: higher levels of corruption are associated with lower levels of FDI. Estimating corruption using the regulatory burden and other controls, we obtain results that are consistent with the findings reported in the literature on regulatory burden (i.e., higher levels of regulation are associated with higher levels of corruption). Finally, when we combine these results and treat corruption as endogenously determined by the extent of regulation, we find that it is the regulatory burden that has the significant effect on the level of FDI inflows. Once corruption is treated as an effect of the regulatory burden, rather than an exogenous factor, its direct effect on FDI is statistically insignificant.

This finding has important policy implications. Both governments and international agencies spend substantial resources on policies aimed at combating corruption. The expenses associated with these policies include both the costs of enforcement, as well as the costs of designing and maintaining detailed location-specific codes of conduct and action plans (e.g., Asian Development Bank, 2006; United Nations, 2001). The effects of these policies have shown up in the delaying or denial of development aid to countries with poor corruption records (Institute for Global Ethics, 2006). These policies are touted as means of improving economic performance and attracting foreign investors. However, it has been recognized that the success of such policies may be doubtful when officials “expend resources to avoid detection and punishment” (Manion, 1996).

Our analysis suggests that such “monitoring” policies fail to address the root cause of the problem. More importantly, they may not have a discernable impact since they are likely to be overwhelmed by the powerful incentives for public officials created by the regulatory burden. Thus, in addition to their direct effect on market efficiency, deregulation and liberalization can have strong indirect benefits through reducing the opportunities for corrupt practices.

References

Adam, A., & Filippaios, F. 2007. Foreign direct investment and civil liberties: A new perspective. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(4): 1038–1052.

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. 1997. National champions and corruption: Some unpleasant interventionist arithmetic. Economic Journal, 107: 1023–1042.

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. 1999. Rents, competition and corruption. American Economic Review, 89(4): 982–993.

Aguilera, R., & Vadera, A. 2008. The dark side of authority: Antecedents, mechanisms and outcomes of organizational corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(4): 431–449.

Asian Development Bank. 2006. Second governance and anti-corruption action plan. Manila: ADB/OECD.

Bardhan, P. 1997. Corruption and development: A review of the issues. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(3): 1320–1346.

Becker, G. S. 1968. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76: 169–217.

Bengoa, M., & Sanchez-Robles, B. 2003. Foreign direct investments, economic freedom and growth: New evidence from Latin America. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(3): 529–545.

Bliss, C., & Di Tella, R. 1997. Does competition kill corruption?. Journal of Political Economy, 105: 1001–1023.

Bowden, R. J., & Turkington, D. A. 1984. Instrumental variables. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buchanan, J. M., & Tullock, G. 1962. The calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Cantwell, J. A. 1995. The globalisation of technology: What remains of the product cycle model?. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19(1): 155–174.

Cantwell, J. A., & Mudambi, R. 2000. The location of MNE R&D activity: The role of investment incentives. Management International Review, 40(Special Issue 1): 127–148.

Cheng, L. K., & Kwan, Y. K. 2000. What are the determinants of the location of foreign direct investment? The Chinese experience. Journal of International Economics, 51(2): 379–400.

Coate, S., & Morris, S. 1999. Policy persistence. American Economic Review, 89: 1327–1336.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. 2008. The effectiveness of laws against bribery abroad. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(4): 634–651.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Dau, L. A. 2009. Pro-market reforms and firm profitability in developing countries. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6): 1348–1368.

Cumings, B. 1984. The origins and development of the Northeast Asian political economy: Industrial sectors, product cycles, and political consequences. International Organization, 38(1): 1–40.

De Haan, J., Lundstrom, S., & Sturm, J. E. 2006. Market-oriented institutions and policies and economic growth: A critical survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 20(2): 157–191.

Dehejia, V. H., & Weichenrieder, A. J. 2001. Tariff jumping foreign investment and capital taxation. Journal of International Economics, 53(1): 223–230.

De Soto, H. 1990. The other path. New York: Harper and Row.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 2002. The regulation of entry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1): 1–37.

Doh, J. P., Rodriguez, P., Uhlenbruck, K., Collins, J., & Eden, L. 2003. Coping with corruption in foreign markets. Academy of Management Executive, 17(3): 114–127.

Doucouliagos, C., & Ulubasoglu, M. A. 2006. Economic freedom and economic growth: Does specification make a difference?. European Journal of Political Economy, 22(1): 60–81.

Dreher, A., & Rupprecht, S. M. 2007. IMF programs and reforms: Inhibition or encouragement?. Economics Letters, 95(3): 320–326.

Dunning, J. H. 1993. Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. 2006. Bargaining for bribes: The role of institutions. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.). International handbook on the economics of corruption: 127–139. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Gillespie, K., & McBride, B. 1996. Smuggling in emerging markets: Global implications. Columbia Journal of World Business, 31(4): 40–54.

Greene, W. 1997. Econometic analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Habib, M., & Zurawicki, L. 2002. Corruption and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2): 291–307.

Harms, P., & Ursprung, H. W. 2002. Do civil and political repression really boost foreign direct investments?. Economic Inquiry, 40: 651–663.

Heineman, B. W., & Heimann, F. 2006. The long war against corruption. Foreign Affairs, 85(3): 75–86.

Henisz, W. J., & Delios, A. 2004. Information or influence: The benefits of experience for managing political uncertainty. Strategic Organization, 2: 389–421.

Hines, J. R., Jr. 1995. Forbidden payments: Foreign bribery and American business after 1997. NBER Working paper no. 5266, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Holmes, S., & Cass, R. S. 1999. The cost of rights: Why liberty depends on taxes. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Husted, B. W. 1994. Honor among thieves: A transaction-cost interpretation of corruption in the Third World. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(1): 17–27.

Husted, B. 1999. Wealth, culture and corruption. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(2): 339–359.

Institute for Global Ethics. 2006. Aggressive World Bank anti-corruption policies prompt backlash from critics. Ethics Newsline, 9(39): 1.

Jakobsen, J., & de Soysa, I. 2006. Do foreign investors punish democracy? Theory and empirics, 1984–2001. Kyklos, 59(3): 383–410.

Kinal, T. W. 1980. The existence of moments of κ-class estimators. Econometrica, 48(1): 241–249.

Klitgaard, R. E. 1988. Controlling corruption. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Knack, S., & Azfar, O. 2003. Trade intensity, country size and corruption. Economics of Governance, 4(1): 1–18.

Kumaraswamy, A., Mudambi, R., Saranga, H., & Tripathy, A. 2012. Catch-up strategies in the Indian auto components industry: Domestic firms’ responses to market liberalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(4): 368–395.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. 2008. The economic consequences of legal origins. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(2): 285–332.

Laffont, J. J. 1996. Regulation, privatization and incentives in developing countries. In M. G. Quibria & J. M. Dowling (Eds.). Current issues in economic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lambsdorff, J. G. 1999. Corruption in empirical research: A review. Working paper, Transparency International, Berlin.

Lambsdorff, J. G. 2003. How corruption affects persistent capital flows. Economics of Governance, 4(3): 229–243.

Li, Q., & Resnick, A. 2003. Reversal of fortunes: Democratic institutions and foreign direct inflows to developing countries. International Organization, 57(1): 175–211.

Lomnitz, L. 1988. Informal exchange networks in formal systems: A theoretical model. American Anthropologist, 90(1): 42–55.

Luo, Y. 2002. Corruption and organization in Asian management systems. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 19(4): 405–422.

Maidment, F., & Eldridge, W. 1999. Business, government and society. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Manion, M. 1996. Corruption by design: Bribery in Chinese enterprise licensing. Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 12(1): 167–195.

Mudambi, R. 1998. The role of duration in MNE investment strategies. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(2): 239–262.

Mudambi, R., Navarra, P., & Paul, C. 2002. Institutions and market reform in emerging economies: A rent seeking perspective. Public Choice, 112(1): 185–202.

Mudambi, R., & Paul, C. 2003. Domestic drug prohibition as a source of foreign institutional instability: An analysis of the multinational extra-legal enterprise. Journal of International Management, 9(3): 335–349.

Mutti, J., & Grubert, H. 2004. Empirical asymmetries in foreign direct investment and taxation. Journal of International Economics, 62(2): 337–358.

Myrdal, G. 1970. Corruption as a hindrance to modernization in South Asia. In A. J. Heidenheimer & M. Johnston (Eds.). Political corruption: Concepts and contexts. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Niskanen, W. 1968. Non-market decision making: The peculiar economics of bureaucracy. American Economic Review, 58(2): 293–305.

Ordover, J., Pittman, R., & Clyde, P. 1994. Competition policy for natural monopolies in a developing market economy. Economics of Transition, 2: 317–343.

Paldam, M. 2002. The cross-country pattern of corruption: Economics, culture and the seesaw dynamics. European Journal of Political Economy, 18(2): 215–240.

Pigou, A. C. 1947. A study in public finance, 3rd ed. London: Macmillan.

Polinsky, M. A., & Shavell, S. M. 2000. The economic theory of public enforcement of law. Journal of Economic Literature, 38: 45–76.

Rodriguez, P., Uhlenbruck, K., & Eden, L. 2005. Government corruption and entry strategies of multinationals. Academy of Management Review, 30(2): 383–396.

Rose-Ackermam, S. 1988. Bribery. In J. Eatwell, M. Milgate & P. Newman (Eds.). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. London: Macmillan.

Rose-Ackermam, S. 1999. Corruption and government: Causes, consequences and reform. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shavell, S. M. 1993. The optimal structure of law enforcement. Journal of Law and Economics, 36(2): 255–287.

Shenkar, O. 2001. Cultural distance revisited: Toward a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3): 519–535.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1993. Corruption. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3): 599–617.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. 1999. The grabbing hand. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Smarzynska, B. K., & Wei, S. J. 2002. Corruption and cross-border investment: Firm-level evidence. Working paper no. 494, William Davidson Institute, Ann Arbor, MI.

Stigler, G. J. 1970. The optimum enforcement of laws. Journal of Political Economy, 78: 526–536.

Stigler, G. J. 1971. The theory of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics, 12: 3–21.

Tanzi, V. 1998. Corruption around the world: Causes, consequences, scope and cures. IMF Staff Papers, 45(4): 559–594.

Trevino, L. J., Daniels, J. D., Arbelaez, H., & Upadhyaya, K. P. 2002. Market reform and foreign direct investment in Latin America: Evidence from an error correction model. International Trade Journal, 16(4): 367–392.

Tung, S., & Cho, S. 2001. Determinants of regional investment decisions in China: An econometric model of tax incentive policy. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 17: 167–185.

United Nations. 2001. United Nations manual on anti-corruption policy. Vienna: Global Programme against Corruption, Centre for International Crime Prevention, Office of Drug Control and Crime Prevention.

Verbeke, A., & Greidanus, N. 2009. The end of the opportunism vs. trust debate: Bounded reliability as a new envelope concept in research on MNE governance. Journal of International Business Studies, 40: 1471–1495.

Verbeke, A., & Kano, L. 2013. A transaction cost economics (TCE) theory of trading favors. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, this issue.

Voyer, P. A., & Beamish, P. W. 2004. The effect of corruption on Japanese foreign direct investment. Journal of Business Ethics, 50(3): 211–224.

Wei, S. J. 2000. How taxing is corruption on international investors?. Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(1): 1–11.

Wheeler, D., & Mody, A. 1992. International investment location decisions: The case of U.S. firms. Journal of International Economics, 33(1–2): 57–76.

World Bank. 2011. Trends in corruption and regulatory burden in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Zhou, J. Q., & Peng, M. W. 2013. Does bribery help or hurt firm growth around the world?. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. doi:10.1007/s10490-011-9274-4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Emerging and developing economies in the dataset:

Argentina, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Cameroon, Chile, P.R. China, Colombia, Congo Dem. R., Costa Rica, Dominican Rep., Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Gabon, Ghana, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Jamaica, Jordan, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritius, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Syria, Thailand, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Uruguay, Venezuela, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mudambi, R., Navarra, P. & Delios, A. Government regulation, corruption, and FDI. Asia Pac J Manag 30, 487–511 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-012-9311-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-012-9311-y