Abstract

Plenty of researchers have explored the relationship between parent firm control and international joint venture (IJV) performance. However, the conclusions of these researchers are inconsistent. Some studies suggest that total control from foreign parent firms produces better outcomes, while other studies consider that shared control or split control structures result in higher IJV performance. All of these studies argue that a parent firm’s control over an IJV would influence the performance of the IJV. This paper contributes to these debates by exploring the control gap, that is, the difference between desired control and exercised control of a parent firm. Evidence from 80 IJVs in Taiwan indicates that control gaps in the areas of manufacturing, financial, and human resource management have negative impacts on IJV performance. Empirical results also show that the level of a parent firm’s resource contribution to an IJV positively influences the parent firm’s desired control. The extent of a parent firm’s learning intent in marketing and R&D management is also positively linked with the degree of control desired by the parent firm. These findings provide important implications for the study of control structure in IJV management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many firms have focused their global strategies on international joint ventures (IJVs) to enter emerging markets, acquire advanced technology, share risks, and obtain complementary resources (Fey & Beamish, 2000; Geringer & Hebert, 1989; Glaister, Husan, & Buckley, 2003; Inkpen & Beamish, 1997). IJVs are an effective means of competing within multi-domestic or global competitive arenas (Harrigan, 1988). An IJV normally involves two or more parent companies at least one of which is headquartered outside of the IJV host country (Harrigan, 1988). Previous research on IJVs and multinational enterprises has focused on control, especially the relationship between control and performance (Geringer & Hebert, 1989; Mjoen & Tallman, 1997; Osland & Cavusgil, 1996; Yan & Gray, 1994).

Control refers to the amount of decision-making power one partner may exercise over an IJV’s daily operations (Choi & Beamish, 2004; Yan & Gray, 2001a). Steensma and Lyles (2000) referred to a control structure as the relative decision-making pattern through which the partners divide power among the parent companies to run a joint venture (JV). Researchers have reached highly inconsistent conclusions on the relationship between control and the performance of IJVs. For instance, according to Hill (1988) and Kogut (1988), dominant control and performance in IJVs are not significantly related to each other. Ding (1997) found that the dominant control of a foreign partner can enhance the performance of US-China JVs, and Beamish (1985) found that shared control is preferable to dominant control by a foreign partner in IJVs in less developed countries. While adopting an organizational justice-based view, some researchers (Barden, Steensma, & Lyles, 2005; Steensma & Lyles, 2000) claim that because shared management can foster mutual respect among IJV partners, shared control can enhance the performance of an IJV. Choi and Beamish (2004) proposed splitting control according to functional expertise. They found that the split control structure performs better than any other approach. This finding suggests that parent companies should choose the activities to control such that those chosen activities can be matched with their respective firm-specific advantages.

A parent firm must control IJV activities for two reasons. First, an IJV can be regarded as a mixed game in which the partners concurrently cooperate and compete with each other (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Khanna, Gulati, & Nohria, 1998; Oxley & Sampson, 2004; Yan & Gray, 2001a). Opportunistic behavior should be a priority concern for a parent firm controlling the specific operational activities of an IJV. According to transaction cost theory, the risk of opportunistic behavior by an IJV partner leads to rent appropriation or a risk of unintended knowledge leakage if multinational corporations (MNCs) bring their valuable resources into an IJV (Choi & Beamish, 2004; Gulati & Singh, 1998; Zeng & Chen, 2003; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002). The ability to prevent IJV partners from engaging in opportunistic behavior depends on the parent company’s ability to maintain its specific advantages. Inkpen and Beamish (1997) suggested that knowledge of the local environment is essential to local parent firms. By contributing and controlling local knowledge, parent firms can place local partners in a vulnerable position that may cause them to increase their dependency on foreign partners. Additionally, because a parent firm can learn from IJV partners, the firms may form an IJV (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Oxley & Sampson, 2004). Lyles and Salk (1996) indicated that, compared with alternative management structures, two-partner JVs exhibit the highest level of knowledge acquisition from foreign partners. Thus, MNCs can acquire core skills or capabilities from their partners by becoming involved in the management process (Tsang, 2000).

Previous scholars have paid considerable attention to exactly how resource contribution and IJV control are related. Blodgett (1991) proposed that a certain combination of resources affects the amount of equity that the parent firm owns. According to Yan and Child (2004a), a party’s ability to control resources that are vital to organizational success gives this party power over the IJV because the ability of an investor to influence some or all IJV activities depends on the investor’s ability to provide better resources than his or her partners. While using a sample of IJVs in China, Chen, Park, and Newburry (2009) found that property-based contributions are linked to output control and process control, whereas knowledge-based contributions are related to process control and social control. The fact that resource contribution affects control is well known. However, exactly how resource contribution affects desired control has seldom been studied. We believe that the specific resource contributions by a parent firm explain the parent firm’s desire to control a specific area.

Most studies treat learning and anti-opportunism (i.e., core knowledge protection) as independent motivations for MNCs entering IJVs (Makhija & Ganesh, 1997; Hamel, 1991; Tsang, 2002; Yan & Gray, 2001a). However, learning and anti-opportunism always coexist (Inkpen, 2000). These two motivations are critical to the control structure through which MNCs dominate the daily operational decision making of the IJV. Therefore, the desire for control increases if a parent company has a strong learning intention or wants to prevent its partners from leaking specific knowledge. The unclear relationship between control and performance leads to the question of whether actual control is greater or less than a parent company desires. We posit that this empirical inconsistency is partially due to a control gap between the expectations and actual circumstances of a parent firm. A control gap refers to the difference between the degree of control that an IJV partner desires to exercise and the degree of control that an IJV partner actually achieves. Some studies have stressed the importance of differentiating between “desired” and “exercised” control (or between what one wants and what one can actually achieve) in IJVs (Yan & Gray, 2001a, b). Chen et al. (2009) suggested that the intent of control does not necessarily manifest itself as an actual influence over IJV activities. Chen et al. (2009) also indicated that the actual exercise of control may depend on a parent firm’s need for control. Rather than being determined by the unilateral intentions of an individual partner, control is a consequence of interpartner bargaining (Yan & Gray, 2001a), foreign direct investment (FDI) legitimacy, local market competition (Li, Zhou, & Zajac, 2009), and other factors. This control gap phenomenon has seldom been addressed. This study demonstrates that parent firms facing different degrees of control gap execute different strategic behaviors, which ultimately influence the performance of an IJV. A control gap may lead to control conflict, which makes it difficult for the partners to manage the IJV (Choi & Beamish, 2004; Geringer & Hebert, 1989; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002) and may cause a higher incidence of instability and failure (Das & Teng, 2000a; Park & Russo, 1996; Steensma & Lyles, 2000; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002). Thus, larger control gaps may degrade IJV performance and cause dissatisfaction for a parent firm. This study closely examines how control gaps and IJV performance are related. As mentioned previously, this topic has been seldom addressed in the literature.

This paper is organized as follows. First, this study reviews the pertinent literature and describes the conceptual framework of the IJV control gap. Next, this study provides theoretical support for the three hypotheses, introduces the research methods, and summarizes the empirical results. Conclusions are drawn and implications for managers and for future research are presented in the final section.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

Many firms focus on IJVs in their global strategies. Firms entering JV agreements strive to create products and services, enter new markets, or pursue both options (Beamish & Lupton, 2009). The strategic motivations for forming JVs also include the following: sharing risks, overcoming impediments such as host-country requirements, collaborating with rivals to manage competition, and integrating resources to obtain a market advantage (Makhija & Ganesh, 1997).

Previous studies have also contended that because alliances provide a platform for organizational learning, they give firms access to the knowledge of their partners (Kogut, 1988). In addition to learning by observing alliance activities and outcomes, firms can learn from their partners through the shared execution of alliance tasks and through mutual interdependence and problem solving (Inkpen, 2000). Because they often bring in technology and management know-how, foreign parent firms are a vital source of useful knowledge in developing countries, whereas a local parent firm with a learning-oriented cooperative strategy usually possesses clear learning intent. Partners must become actively involved in related organizational management procedures in which the knowledge is embedded to learn knowledge (Makhija & Ganesh, 1997). However, parent firms with less control over the IJV may lack the opportunity to become involved in the practical management of the IJV to access the target knowledge. This perspective can explain why a parent firm may have a desired control area that is not aligned with its real control area. Greater strategic knowledge and an increased contribution of resources normally imply that the partners desire great control over the IJV. Furthermore, Child and Faulkner (1998) indicated that parent firms should exercise control selectively over the activities and decisions that the parent firm regards as critical. IJV owners may concentrate on providing certain resources and controlling major decision areas and related activities, whereas parent firms seek to exercise more control over the strategic management of the IJV (Glaister et al., 2003).

Control gap framework of IJV control

IJV control is defined as the influence exercised by a partner over the operations of the IJV (Geringer & Hebert, 1989). Geringer and Hebert (1989) proposed that there are three dimensions of IJV control: the focus of control (i.e., the scope of the activities over which the parents exercise control); the extent or degree of control that the parents achieve; and the mechanisms that the parents use to exercise control. This study explores the first two dimensions of control. Prior studies of control have extended the concept from wholly owned international subsidiaries to the context of IJVs and have adopted a strategic perspective focusing on the relationship between the international strategy of the MNC, the strategy of the other partner, and IJV control (Yan & Gray, 2001a). Control refers to a conduit through which the specific advantages of a parent company are transferred to a venture. The allocation of management control can be influenced by the contribution of resources (Lecraw, 1984; Yan & Gray, 1994, 2001a). The inability of parent firms to hold all of the resources necessary to render the IJV successful leads to resource contribution asymmetry among the partners. Transaction cost theory suggests that a firm with more specific advantages tends to exercise greater control over an overseas subsidiary to prevent its firm-specific advantages from unintentionally spilling over to a local partner (Williamson, 1985). A partner must control some IJV activities to prevent unintended core knowledge leakage or to appropriate rent (Inkpen & Beamish, 1997; Tsang, 1999; Yan & Gray, 2001a; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002). Choi and Beamish (2004) suggested that MNCs can partition management control according to resource contributions. In split control, partners take responsibility for managing those functions in which they excel, whereas in shared control, both partners mutually share responsibility for all functions (Choi & Beamish, 2004). For instance, an IJV partner with marketing expertise should exert control over the IJV’s marketing-related activities. Therefore, an MNC’s desire to control a specific function could be positively related to its resource contributions toward the specific function.

Based on a survey of 178 foreign companies operating in China, Luo (1999) suggested that compared with Western firms, Asian MNCs are inferior in technological and organizational competencies but superior in host country-specific knowledge, such as marketing tactics and environmental familiarity. Despite these differences, knowledge in all four dimensions is found to enhance financial returns and overall performance in China no matter where knowledge comes from. Thus, parent firms tend to acquire useful knowledge from their oversea ventures to enhance their own performance. Luo, Shenkar, and Nyaw (2001) suggested that US partners prefer to have more dominant overall control of Chinese JVs than Chinese partners do, whereas Chinese partners prefer to have specific control over functional areas because they are more interested in technology transfer than in overall control. Simonin (2004) defined learning intent as an organization’s desire and will to learn from its partner or from a collaborative environment. According to Yan and Luo (2001), knowledge transfer between JV partners is closely related to each partner’s desire for such knowledge. A partner occasionally wishes to access the other partner’s knowledge that is brought to the IJV through management participation (Inkpen & Beamish, 1997; Luo et al., 2001; Tsang, 1999). As a consequence, learning intention positively impacts an MNC’s desire for control.

Rather than being independent of each other, learning and core knowledge protection always coexist as strategic issues if MNCs form IJVs (Kale, Singh, & Perlmutter, 2000). Both issues must be addressed if an MNC wants to learn from its IJV partner while preventing its own core knowledge from unintentionally leaking to the partner. MNCs can learn from their partners and protect their core knowledge by exerting management control. Therefore, an MNC and its local partners may desire to control the same operational activity of the IJV. If a JV partner exerts a greater degree of control over an IJV, the JV partner is more capable of achieving its own strategic objectives for the IJV at the expense of the other partners’ objectives (Yan & Gray, 2001a). However, if one partner achieves more management control, the interests of the other partners have likely been sacrificed. A control gap emerges if an MNC’s actual control over a specific operational activity is lower than its desired control. In this situation, MNCs may strive for more control power because they feel unsatisfied. This control gap may lead to a management control conflict among the parent companies, which, in turn, may damage the cooperative atmosphere and lead to further mistrust among the partners (Barden et al., 2005; Kale et al., 2000; Zeng & Chen, 2003). Although a parent firm with high control can reduce the possibility of knowledge leaks and allow an IJV to be integrated into the firm’s overall strategy, the exercise of IJV control is not without drawbacks. Control often implies a commitment from a parent firm in terms of both responsibility and resources, and may lead to increased overhead costs (Anderson & Gatignon, 1986). Geringer and Hebert (1989) noted that the exercise of extensive control over an IJV’s activities and decisions can generate significant coordination costs and limit the efficiency of an alliance. This is especially true for control efforts oriented toward activities and decisions that MNCs perceived to have little importance for either performance improvements or strategic goals achievements. In this scenario, the parent firm may desire less level of control than its exercised level of control. If a parent firm’s actual control level in an IJV differs from its desired level, the parent firm may be not willing to contribute critical skills and assets (e.g., technology and management practices) (Mjoen & Tallman, 1997). This unwillingness negatively impacts the IJV’s competitive position and performance.

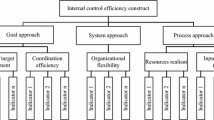

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the control gap and IJV performance.

Resource contribution and parent firm’s desired level of control

Resource complementarity and learning are two critical factors that motivate MNCs to form JVs (Choi & Beamish, 2004; Das & Teng, 2000b; Park & Russo, 1996; Tsang, 2000). The application of the resource-based and resource dependency views to parent firms’ control provide insights into how resources can improve a firm’s strategy and behavior through their ability to influence subsidiary control decisions. Thus, as a central component of the parent–subsidiary relationship, resource contribution seems to be an appropriate focus for exploring the control of parent firms (Chen et al., 2009). Many resource contributions made by parent firms can be classified as either capital or noncapital resources or differentiated into various functional resources, including human, financial, technological, managerial, or marketing resources. Notably, there is asymmetry in the resource contributions among partners if each parent firm brings its own specific resources to the IJV. This resource asymmetry can trigger two appropriation concerns regarding the opportunistic behaviors of partners (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Luo et al., 2001; Yan & Gray, 2001a; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002). The first concern, rent appropriation, relates to an MNC’s ability to capture a fair share of the rents from the IJV (Barden et al., 2005; Gulati & Singh, 1998; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002). Accordingly, a JV partner may only obtain a fair share of the rents from the IJV if it can effectively control the IJV (Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002). Knowledge leakage is the second appropriation concern. Control can be an effective means of protecting specific assets and reducing uncertainty if there are frequent interactions among different organizations. In the parent–IJV relationship, parent firms exercise control to protect their investments and prevent opportunistic behaviors (Hamel, 1991), whereas MNCs seek to prevent the leakage of valuable knowledge or core technologies (Larsson, Bengtsson, Henriksson, & Sparks, 1998; Tsang, 1999). Das and Teng (1998) referred to this concern regarding leakage as a relational risk. Recent empirical studies suggest that an MNC may choose an appropriate mode of governance to balance the competing interests of joint value creation and knowledge leakage (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Kale et al., 2000; Khanna et al., 1998; Zeng & Chen, 2003). Nevertheless, many studies suggest that the control that a parent company exerts over some or all of an IJV’s activities helps to protect the parent firm from the risk of prematurely exposing its technological or other proprietary assets to its other partners (Geringer & Hebert, 1989; Groot & Merchant, 2000; Yan & Child, 2004b; Yan & Gray, 2001a). Similarly, local partners may have incentives to pursue opportunism by exploiting the proprietary technology of their foreign partners (Beamish & Banks, 1987; Kogut, 1988), especially in a country with weak protection of intellectual property rights (Oxley, 1997). Some studies suggest that the threat of an initially weaker IJV partner obtaining a competitive advantage through a superior ability to learn from collaboration also increases the need to control activities and information flows in the IJV (Hamel, 1991; Makhija & Ganesh, 1997). Moreover, the frequent interactions and involvement typically found in an IJV can make it easy to absorb and misappropriate the firm-specific advantages of the MNC (Beamish & Banks, 1987; Geringer & Hebert, 1989; Park, 2010; Woodcock, Beamish, & Makino, 1994). This perspective, with its emphasis on the importance of control and reductions in the risk of appropriation (Beamish & Banks, 1987), suggests that the parent firm needs a high level of control over the specific critical resources contributed by the parent firm to the JV.

Therefore, controlling the IJV is increasingly important if a parent firm transfers critical strategic resources to the venture. The specific resources contributed by the parent firm increase its expectation of control over particular functional activities of the venture. In other words, a parent firm that contributes a significant amount of manufacturing resources and knowledge expects a high level of control and influence within the field of operations (Barden et al., 2005). As a consequence, an IJV partner that contributes more specific knowledge tends to exercise more control over the IJV (Choi & Beamish, 2004; Mjoen & Tallman, 1997; Yan & Child, 2004b). Because a parent firm that contributes its critical strategic resources to a JV intends to have control, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1

A parent firm’s resource contribution of a specific function is positively related to the level of the firm’s desired control over that specific function.

Learning intent and parent firm’s desired level of control

According to the resource-based view, a firm is a bundle of many resources whose attributes significantly affect the firm’s competitive advantage (Barney, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984). Successful business operations often require multiple resources to obtain a competitive advantage. IJVs are allegedly formed to achieve superior resource combinations that single firms cannot achieve independently (Das & Teng, 2000b). The growth of global competition has underlined the importance of acquiring and internalizing crucial skills in a timely manner to strengthen a firm’s competency. IJVs make it possible to acquire rapidly the unique competencies of other firms (Hamel, 1991; Kogut, 1988). Researchers note that IJVs are an effective vehicle for coping with the competition and rapid technological changes that characterize the intensely competitive international environment (Makhija & Ganesh, 1997) because the skills and knowledge underlying global competitiveness are often embedded in different international contexts, as are the institutional and cultural aspects that are not easily transferred without a participative settling such as an IJV (Makhija & Ganesh, 1997). For firms seeking to enter foreign markets, not all potential foreign market entrants possess sufficient knowledge of local market conditions to earn acceptable returns on their resources or can develop such knowledge in a timely and cost effective manner (Madhok, 1997). Collaborating with local partners allows a foreign firm entering a foreign market to compensate for these limitations in its knowledge base (Luo, 2001).

Learning intent refers to the level of a parent firm’s desire and will to learn from its partners. The strategic motives of MNCs largely determine their control focus (Yan & Luo, 2001). Learning intent could have either existed before the IJV was formed (Gulati & Singh, 1998; Oxley & Sampson, 2004) or emerged from the process of cooperation (Tsang, 1999). MNCs may form JVs because they hope to either remedy a resource deficiency or take advantage of an opportunity that they fail to realize on their own. Inkpen (2008) contended that a JV creates valuable and exploitable learning opportunities. As foreign parent firms normally bring in technology and management know-how, they serve as vital sources of useful knowledge in developing countries. A local parent firm that has adopted a learning-oriented, cooperative strategy usually possesses a clear learning intent. According to previous studies, the outcomes of many Japan–West alliances adversely impacted the Western firms while benefitting the Japanese partners, partially because of the Japanese partners’ clear intent to acquire specific knowledge from the Western firms (Teramoto, Richter, & Iwasaki, 1993). While discussing learning-intent JVs, Makhija and Ganesh (1997) argued that a knowledge transfer requires the partners to participate actively in the relevant organizational processes in which the knowledge is embedded. Tsang (2002) identified overseeing effort and management involvement as effective ways to acquire knowledge from a JV. His finding indicates that firms improve their knowledge acquisition skills through learning-by-doing. That is, parent firms must become involved in the practical management of the IJV to access the target knowledge that the parent firm is lacking.

Makhija and Ganesh (1997) asserted that control processes are a primary means through which learning occurs within a JV. For those IJVs in which the JV and the foreign parent firm may not be in close geographical proximity to each other, the managers within the parent firm are responsible for communicating with the JV and monitoring its performance. Otherwise, the JV normally entails submitting regular reports to the parent firm on routine issues related to financial matters, production, personnel, and local market situations. The extent to which the parent managers understand the venture operations largely determines the degree of knowledge learning. Lyles and Salk (1996) supported the notion that expatriate managers represent an effective medium for knowledge acquisition, as a parent firm can access its partner’s knowledge by actively participating in IJV managerial activities (Inkpen & Beamish, 1997; Tsang, 2002). This argument suggests that compared with alternative management structures, two-partner JVs have the highest level of knowledge acquisition from the foreign partners. If a parent firm attempts to exercise a significant amount of control over an IJV’s specific functional areas, the parent firm likely seeks to acquire knowledge or technologies from the foreign partner (Luo et al., 2001). In other words, by forming an IJV, parent firms create the opportunity to acquire knowledge from their partners. However, the strength of a parent firm’s control over an IJV influences the possibility and the degree of knowledge acquisition. In sum, parent firms that intend to learn a great deal from their partners should strongly prioritize control over the IJV. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 2

A parent firm’s learning intent regarding a specific function is positively related to the level of the firm’s desired control over that specific function.

Control gap and IJV performance

This paper focuses on the gap between the parent firm’s desire for control and the actual exercise of control. One of the many factors affecting the parent firm’s ability to obtain a desired level of control over the IJV is the local government (Yan & Gray, 2001a), which plays a particularly significant role for the IJVs in developing and transitional economies. Meschi (2009) analyzed the relationship between the corruption of local governments and the changes in the equity stakes of foreign partners in IJVs. His findings show that local government corruption is significantly related to the likelihood that the foreign partners will terminate the IJV. Kilduff (1992) contended that despite their desire for more control, parent firms find it difficult to implement their own operating routines in IJVs because the parent firms’ systems may be deeply rooted in certain cultural assumptions and values that are not necessarily shared by the IJV or other firms. Meanwhile, not all IJV parent firms consider the partnership equally important to their overall strategic portfolios. In addition, a parent firm likely utilizes its control if it views an IJV as strategically important (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1986). Thus, the firms that view the IJV as less strategically important have less desire for control. In the parent firm–IJV relationship, a parent firm’s need for control tends to increase with the strategic importance of the IJV (Martinez & Ricks, 1989), and a parent firm participating in an IJV intends to achieve specific goals. Thus, the IJV has a certain degree of importance for the parent firm. If an IJV is viewed as an important part of the parent firm’s competitive strategy or is a major profit contributor, the parent firm is likely to increase its management control in venture activities and to send more expatriates to the venture to ensure its success. Although the IJVs that are peripheral to the parent firm’s strategy often receive less attention, a parent firm commits more resources and attention to the IJVs that are strategically important (Cullen, Johnson, & Sakano, 1995). Therefore, if the parent firm considers the IJV to be less important, the firm exhibits less need for control. However, the difference between desired and exercised control (i.e., the difference between what one wants and what one actually achieves) must be noted (Yan & Gray, 2001b). Yan and Gray (2001a) suggested that if an IJV is strategically important to a partner, this partner more heavily depends on the other(s) and can achieve less management control. Therefore, a greater degree of strategic importance may cause the partner to exhibit less control over the venture than a partner desired.

A positive control gap exists if the actual level of control exceeds the desired level of control. Proposing an attention-based theory of the firm, Ocasio (1997) asserted that a firm’s behavior is the result of how the firm channels and distributes the attention and focus of its decision makers. What managers actually decide depends on the issues upon which they focus their attention. In turn, the focus of their attention depends on the particular context in which they find themselves and on how the firm’s rules, resources, and social relationships distribute the issues and the decision makers among the specific activities. For example, if a parent firm follows an output-oriented strategy, this strategic orientation will serve as a main guideline for channeling managerial attention. In other words, the strategic importance of the output or the outcome of an IJV in general naturally becomes a key determinant of managerial attention. Thus, the greater the strategic importance of an IJV, the more resources and attention the parent will commit to it (Cullen et al., 1995; Tsang, 2002). It is already widely acknowledged that subsidiaries evolve over time. Head-office assignments, subsidiary choices, and local environment determinism are the three mechanisms that interact to determine the subsidiary’s role. Consequently, the subsidiary’s role impacts not only the decisions made by the head office managers and the subsidiary managers but also the standing of the subsidiary in the local environment (Birkinshaw & Hood, 1998). For instance, a decrease in the host government’s support or in the strategic importance of the host country is likely to have a significant and negative impact on the importance of the IJV. If an IJV is less important to a parent firm, the parent firm is likely to withdraw its resources from the IJV and thus allow the partner to gradually assume responsibility for and control of the IJV. In this scenario, the control level desired by the parent firm is less than its actual control level, and a positive control gap exists. As a result, the parent firm will likely increasingly reduce the input of its resources into the IJV and reallocate its resources to other areas. In a survey of 126 IJVs in Korea, Park (2010) found that the support of foreign parents in various managerial functions will considerably increase the extent of knowledge acquisition for the IJVs. The acquisition of this external knowledge leads to an improvement in organizational routines and ultimately results in performance enhancement (Park, 2010). Conversely, if the parent firm fails to invest its efforts into the IJV operations, the IJV may exhibit an inferior performance.

A negative control gap exists if the desired control level exceeds the level of actual control, and the parent firm often faces conflicts due to irreconcilable desires in a cooperative relationship. Consequently, procedural conflict is inherently linked to the issues surrounding the distribution of control and responsibility in a cooperative relationship (Barden et al., 2005). Conflicts over task coordination, procedural fairness, and outcome distribution are often associated with negative emotions and time-consuming discourse, which subsequently creates a drag on firm performance (Barden et al., 2005). A situation in which a JV partner’s control over the IJV increases the coordination cost reduces the IJV’s effectiveness (Pearce, 1997). Furthermore, control-related conflicts among partners likely give rise to distrust and tension while significantly and negatively impacting the IJV’s performance (Ding, 1997). Geringer and Hebert (1989) suggested that coordination and conflict among partners as well as unintended disclosures of knowledge could increase the transaction costs associated with opportunistic behavior. This increased cost can subsequently limit the potential gain from the IJV. Consequently, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3

A parent firm’s control gap (i.e., the difference between desired control and exercised control) is negatively related to the performance of the IJV.

Methodology

Sample and data collection

The data for this study were collected through a questionnaire survey of IJV executives from JV parent firms. The executives were expatriates from various countries. Because expatriates in MNCs usually communicate easily in English (Chang & Taylor, 1999), the questionnaire was designed in English. Nonetheless, a translation was prepared by two bilingual scholars to verify the correctness of the questions in the English questionnaire. As a result of the review, the authors and a bilingual scholar identified and corrected a few inconsistencies. The population consisted of firms that had established JVs in Taiwan because Taiwan is one of the fastest growing emerging economies in Asia. Taiwanese IJVs formed by MNCs were used to test this framework. The samples were mainly based on D&B Foreign Enterprises in Taiwan, which was published by Dun and Bradstreet International Ltd. The ownership of the IJV partners had to fall in the range between 20% and 80% of total equity, as the IJVs with equity shares outside of this range are typically treated as wholly owned subsidiaries (Burton & Saelens, 1982; Choi & Beamish, 2004). Because 39 of the 688 potential targets could not be considered as IJVs based on the above criteria, these firms were deleted from the target list.

The data collection process was divided into two stages. During the first stage, initial contact with each IJV was made via fax or telephone. Actual contact was made with only 553 IJVs because of incorrect telephone numbers, wrong addresses, or the dissolution of the IJV. Of the 553 IJVs, 254 agreed to participate in the survey (a participation rate of 45.93%). During the second stage, 254 questionnaires were sent to these IJVs, but only 87 were returned after a six-month period that included follow-up contact by telephone. Of the 87, only 80 questionnaires were usable. The response rate was 31.50%. Among the respondents, 43 were from Northeast Asia (e.g., Japan and Korea), 13 were from Europe and North America, 19 were from Southeast Asia, and the remaining five were from Australia and New Zealand.

The representativeness of the samples collected was checked using a set of t-tests. Eighty non-responding IJVs were randomly selected and compared with the responding IJVs. The authors then examined the ownership structure (i.e., the percentage of equity owned by foreign partners), the size of the investment (i.e., the total capital investment) and the years of establishment (i.e., the number of years in Taiwan). Because the t-test results were all insignificant, we concluded that there was no significant non-response bias in our sample.

Owing to our reliance on self-reported data, this study examined whether common method variance was a likely threat that could inflate the results of the hypotheses testing. First, common method variance was tested using Harman’s single-factor test, as proposed by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (2003). All of the questionnaire items were entered together into a factor analysis. Because no single factor emerged and the first factor did not account for a majority of the variance, Harman’s single-factor test indicated that common method variance is insignificant (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Next, Harman’s single-factor test in CFA was conducted. The results of the analysis indicated that a single-factor model did not fit the data well (χ2 = 4644, χ2/df = 4.3, IFI = .287, CFI = .280, RMSEA = .208). Additionally, the chi-square difference test also revealed that the single-factor model and the five-factor model significantly differed from each other (Δχ = 678.5, Δdf = 10, p < .000). Thus, the above tests indicated that common method bias did not seriously distort the analytical results.

Variables and measurements

Appendix 1 presents the questionnaire items associated with the four constructs of the theoretical model.

Resource contribution

The 15 items used to measure this construct reflect five types of resource contributions related to business functions: manufacturing, marketing, finance, R&D, and human resource management (HRM). The three items used to measure manufacturing contribution included knowledge of production management, quality assurance, and factory layouts. The four items used to assess marketing contribution included knowledge of pricing setting, sales channels, promotional activities, and product selling, whereas the three items used to measure finance contribution included general financing, medium-term financing, and financial planning capabilities. The two items used to measure R&D contribution were R&D capabilities for new products and production. Finally, the three items used to determine HRM contribution were human resource planning, top management personnel, and mid-management personnel. The respondents were asked to assess the relative source contributions of the subsidiary resources and their capabilities using a seven-point Likert scale. The subscales of resource contributions were constructed based on the average score of the degree of resource contributions in each functional area. The Cronbach’s alpha for this construct was .93.

Learning intent

As Tsang (2002) mentioned, the intent to learn refers to a firm’s determination or commitment to learn certain skills from the other partners of a strategic alliance or an IJV. This construct was measured based on a seven-point Likert scale. The Cronbach’s alpha for this construct was .89.

Control gap

This term is defined as the difference between desired control and exercised control. Previous studies indicate that a partner controls an IJV with the following five functions: manufacturing decisions, marketing decisions, financial decisions, R&D decisions, and HRM decisions (Choi & Beamish, 2004; Steensma & Lyles, 2000; Tsang, 1999). Accordingly, 12 items were used to measure this construct. The three items used to measure manufacturing control included decisions regarding production management, quality control, and factory layouts. The three items used to determine marketing control included decisions on pricing setting, sales channels, and product promotion. The three items used to assess financial resource control were general financing, long- and medium-term financing, and financial planning. The two items used to determine R&D control were decision making regarding new products and production. The one item used to measure HRM control was human resource planning. The respondents were asked to identify the desired degree of control by indicating how important the above mentioned issues were on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = very unimportant, 7 = very important). The respondents were also asked to identify the degree of control exercised by their partner over the above mentioned functions using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = no control at all, 7 = complete control). By drawing on the measure employed by Barden et al. (2005), the control gap is expressed as follows:

where CG denotes the degree of the control gap experienced by the parent firm; CDi represents the parent firm’s desired level of control over the ith management activity (e.g., manufacturing, marketing, finance, R&D, and HRM); and CEi refers to the level of control exerted by the parent firm over the ith management activity. The Cronbach’s alpha of the difference was .95. A logarithmic transformation was performed to normalize the distribution (Barden et al., 2005).

IJV performance

Although profitability and stock market returns are common financial indicators of performance, they are less frequently used in scholarly research for the following reasons: (1) they are often unavailable in public databases, especially in the case of IJVs; (2) JVs usually do not issue or trade stocks on the market; and (3) financial measures are occasionally inapplicable given the objectives of a JV (Beamish & Lupton, 2009). Geringer and Hebert (1991) indicated that there is a high correlation between the subjective and objective measurements of an IJV’s performance. The term “IJV performance” refers herein to the degree of perceived satisfaction in the following four areas: strategic goal achievement, cooperative relationship among IJV partners, willingness to continue the alliance, and overall satisfaction. Previous studies on IJV control and performance have used this measurement scale (Ariño, 2003; Choi & Beamish, 2004; Luo & Park, 2004; Yan & Gray, 2001a). The responses collected (on a seven-point scale) are used to evaluate IJV performance. The Cronbach’s alpha for this construct was .96.

Control variables

This study has four control variables. The first control variable is the ownership of foreign partners. Ownership is the percentage of equity owned by the foreign parent and can be a source of bargaining power (Yan & Gray, 1994, 2001a). Therefore, ownership can also serve as a control mechanism (Pearce, 2001). Increasing ownership implies an increasing degree of control (Chang & Taylor, 1999). The second control variable in the regression analysis is the age of the IJV, which is calculated by subtracting the year of formation from the year of this survey. Given that the nationality of the foreign parent firm may have some systemic effects on the relationship’s interest because of cultural differences, the model included a dummy variable that differentiated the IJVs with culturally Western foreign parent firms from the IJVs with culturally Eastern foreign parent firms. A value of 1 was assigned to the IJVs with foreign parent firms from Western cultures. Additionally, if the goals between foreign and local parent firms’ objectives are incongruent, one partner is likely to resist control from the other and likely to view such control as detrimental to IJV performance (Luo et al., 2001). Because goal congruence between foreign and local parent firms’ objectives may systemically affect the results of the study, the respondents were asked to assess the level of goal concordance between the parent firm and the partner on a seven-point Likert scale.

Table 1 lists the means and standard deviations of each variable as well as the pair-wise correlations between variables.

Results

Resource contribution, learning intent, and parent firm’s desired level of control

Because resource contribution and learning intent may simultaneously affect the two variables (desired control and exercised control), we tested H1 and H2 with seemingly unrelated regressions (SURs). SUR models are a multivariate regression technique. The only difference between the SUR model and the more popular ordinary least squares (OLS) model is that the SUR model simultaneously estimates the desired and exercised level of control and allows the error terms to be correlated. Thus, the correlation coefficients are expected to contain additional information that is useful for the analysis. Using the SUR model to estimate the equations simultaneously, we can improve efficiency. An efficient estimator is desirable because it is the minimum variance unbiased estimator. Thus, all standard errors are better estimated with the SUR model than with the OLS regression. The model we tested consists of the following two equations:

where DC = desired control, RC = resource contribution, AG = age of IJV, OW = ownership, NA = nationality of the foreign parent, and EC = exercised control. Regarding the correlations of the error term, there is a significant positive correlation between equation (1) and equation (2), with a coefficient of .353. This finding indicates that a change in the desired control will coincide with a corresponding change in the exercised control. Based on this result, however, it is not possible to draw a conclusion on causality. The SUR results are reported in Table 2. Whereas Model 1 predicts the degree of desired control, Model 2 predicts the degree of exercised control. Because H1 and H2 are related to desired control, we only use information from Model 1 to test these hypotheses. Model 1 examines how the control variables are related to the firm’s desired level of control. Foreign parent nationality is a significant predictor of desired control because the foreign parent firms from Western cultures are more likely to desire control than the foreign parent firms from Eastern cultures. Hypothesis 1 suggests that a parent firm’s resource contributions are positively related to its desired level of control over the IJV. This study demonstrates that if the levels of resource contribution are high, the desire to avoid knowledge leakages increases the likelihood that the parent company will want to control the IJV. As expected, resource contribution has a positive effect on desired control (β11 = .799, p < .001). Hypothesis 2 predicts that learning intent increases the likelihood that parent firms will want to acquire more control. This study demonstrates that the parent firm can access its partners’ knowledge by becoming actively involved in IJV management and that parent firms can acquire knowledge of its partners by exercising greater control over the IJV. Therefore, learning intent and desired control are positively related. In Model 1, the coefficient associated with learning intent is insignificant (p > .1). Multicollinearity is tested by a variance inflation factors (VIF) test, and the VIF values for these models are all below 2, which suggest that multicollinearity is not a significant concern.

This study closely examined how each business function influences and is related to the desired level of control. In Table 3, Model 1 indicates that, although manufacturing contribution and desired level of control over manufacturing are positively and significantly related, learning intent and desired level of control over manufacturing are not significantly related. Model 2 reveals that both marketing contribution and marketing-knowledge learning intent are positively and significantly related to desired level of control over marketing. According to Model 3, although finance contribution and desired level of control over finance are significantly related, finance-knowledge learning intent and desired level of control over finance are not. Model 4 indicates that R&D contribution is positively and significantly related to desired level of control over R&D, and that R&D-knowledge learning intent is significantly related to desired level of control over R&D. Model 5 reveals that, although HR contribution and desired level of control over HR are positively and significantly related, HR-knowledge learning intent and desired level of control over HR are not. VIF values for these models are all below 2, which implies that multicollinearity is not a significant concern. This evidence supports H1 and suggests that resource contribution is positively related to the desired degree of control. However, H2 is only supported with regards to marketing and R&D.

The empirical results support the hypothesis that a desire for control is accompanied by a resource contribution. That is, resource contribution is a significant driver of desired control. This finding is consistent with that of Tsang’s (2002) study, which asserts that what managers’ decisions depend largely on the issues and answers upon which the managers focus their attention. Namely, greater resource allocation to a JV implies that the parent firm desires a greater degree of control. However, a parent firm with a clear learning intent in only marketing or R&D functions has a strong desire for control. This finding implies that control may not be an ideal mechanism to acquire all of the knowledge available from IJVs. In the process of learning capabilities from partners, Makhija and Ganesh (1997) noted that a key consideration is the codifiability of the knowledge inherent in the capability. Highly codifiable knowledge is related to highly tangible resources, such as capital and other assets, raw materials, and regulatory permits that can be easily extricable and transferable from a given environment. Because R&D and marketing knowledge are often embedded in the firm’s organizational processes, the partners desire to participate actively in the relevant organizational processes in which the knowledge is embedded.

Control gap and IJV performance

Table 4 summarizes the results of the regression models. The regression model in Model 1 examines how the control variables are related to the IJV performance. The variance explained for this model is .593 (p < .001), and the strong, significant, positive predictor is goal congruence. The results of all of the regressions suggest that the goal congruence of the IJV parent firms is positively related to performance.

Hypothesis 3 states that the control gap is negatively related to the performance of the IJV. Multicollinearity is further excluded by testing of variance inflation factors. VIF values (≤ 2) for these models rule out a multicollinearity problem. In Table 4, Model 2 reveals that a control gap significantly and negatively impacts the performance of the IJV. This finding suggests that the gap between desired control and exercised control is negatively related to performance. Models 3 to 7 show the regressions that explore how each function of the control gap and firm performance are related. Additionally, the control gap related to the manufacturing, financial, and human resource functions is negatively and significantly related to IJV performance. Because this finding suggests that a control gap in manufacturing, financial and/or human resource functions negatively influences performance, H3 is partly supported.

An increase in the control gap related to the manufacturing, financial, and human resource functions in an IJV decreases the performance of the IJV. This finding suggests that these three functions should not differ with respect to the desired and exercised degree of control. For a partner exerting control over or under the desired level, the IJV’s performance is likely to suffer because of the decreased degree of control incongruity. Barden et al. (2005) argued that parent firms easily face conflicts arising from irreconcilable desires in a cooperative relationship and that these conflicts are inherently linked to issues surrounding the distribution of control and responsibility within a cooperative relationship. The unsupported relationship between the control gap related to marketing and research development and performance is unexpected and may be due to the unique nature of IJVs in Taiwan. Examining 640 international alliances in Taiwan, Wen and Chuang (2010) attested to the embedded knowledge asymmetry between emerging partners and their foreign partners due to the later-comer status in the economic developmental stage. A foreign parent firm is motivated to join a cooperative venture in Taiwan because it desire to increase its technological knowledge and expand into overseas markets. Therefore, a foreign parent firm may tolerate control incongruity that does not necessarily lead to conflicts between itself and its local partners.

Discussion and conclusions

Control in IJVs can be divided into three dimensions: mechanisms of control, focus of control, and degree of control (Geringer & Hebert, 1989; Groot & Merchant, 2000). Most studies focus solely on control mechanisms (Baliga & Jaeger, 1984; Doz & Prahalad, 1984; Edström & Galbraith, 1997; Nobel & Birkinshaw, 1998). Although some studies have found that management control and IJV performance are related, these conclusions remain contentious. Accordingly, some studies suggest that dominate control by foreign partners can result in better performance (Ding, 1997; Glaister & Buckley, 1998; Hill, 1988; Kogut, 1988), whereas other studies insist that shared management control enhances the performance of IJVs (Barden et al., 2005; Beamish, 1985; Steensma & Lyles, 2000). Recently, however, Choi and Beamish (2004) proposed a split control model, which demonstrates that partitioning management control according to each partner’s specific advantage can increase satisfaction. The contentious issue regarding control in IJVs is whether MNCs can control the specific management function that they desire to control. As its first contribution, this study provides a control gap framework to show that the control structure may not be a major determinant of an IJV’s performance, though a control gap can influence an MNC’s perception of IJV satisfaction. Even if MNCs dominate most of an IJV’s daily operational activities, the inability of MNCs to control the specific IJV operational activity that they want to control leads to their dissatisfaction with the performance of the IJV. Closely examining the extent of control desired by the parent firms of the IJV reveals that this study complements previous studies that have mainly examined exercised control. Furthermore, whereas most IJV studies focus on the effects of a parent firm’s exercised control on performance, this study explores how a control gap influences the performance of an IJV. The results of the analysis confirm the importance of a control gap to the performance of IJVs. The findings related to the parent firm’s control gap shed further light on an important yet under-researched area of IJVs. Our findings significantly contribute to the IJV management literature by elucidating the relationship between control gaps and IJV performance. The control gap is critical to the success of an IJV.

Why has a control gap emerged? The control gap is positively related to an MNC’s desire to control a specific IJV operational activity. We contend that the resources contributed by the parent company influence its focus and degree of control. Our results also find empirical support for a direct relationship between the amount of contributed resources and the desired degree of control. A parent firm’s strategic intention is a critical determinant of the way in which control is focused (Yan & Luo, 2001). Furthermore, although learning from the other partners is often a strategic aim of the MNCs involved in an IJV (Inkpen & Beamish, 1997; Luo et al., 2001; Tsang, 1999), the empirical findings indicate that some learning intentions directly affect the amount of control desired.

Most studies assume that anti-opportunism and learning are two independent variables that contribute to the success of an IJV. We posit that because these two issues coexist. IJV control is also required to consider these two motivations simultaneously. This work provides further insight into the focus and degree of control in IJVs. Furthermore, this study has some useful implications for IJV managers and policy-makers. First, appropriability refers to the MNC’s ability to capture the rents generated by the valuable resources that are brought into an IJV. MNCs must effectively reduce appropriability hazards through management control to secure the rent appropriation. This fact explains why MNCs want to dominate and control IJV operational decisions. Although IJVs usually serve as a mode of entry, which used to be a mechanism for MNCs to overcome opportunistic behaviors (Dhanaraj, Lyles, Steensma, & Tihanyi, 2004), the IJV itself (or the level of ownership) does not equally affect the degree of control needed to deter the partners’ opportunism. The share of equity is not positively related to the share of control (Yan & Gray, 1994). As Choi and Beamish (2004) suggested, if MNCs lack the expertise or knowledge required to manage the local partner’s firm-specific advantages, MNCs should not exercise control over these advantages. If an MNC wants to exercise control over a partner’s specific advantage, the MNC can reduce rent appropriation concerns, but they may increase another partner’s control gap as a result. This control gap renders coordination more difficult and detracts from the performance of the IJV. Second, this study thoroughly elucidates control in IJVs to examine the focus of control and its division over specific single functions. The results of this study are also beneficial for managers who do not want to limit themselves to a global, overall perspective of control. However, a parent firm contributes functional resources to control its own functional activities and decisions. The control gap that arises from a difference between the parent company’s desired level of control and its exercised level of control is minimized, which subsequently improves the IJV performance. This finding may explain why split control can increase satisfaction with respect to IJV performance.

Despite its contributions, this study has certain limitations. First, because this study examines only the control gap from the perspective of a single JV partner, these findings are limited to the view of one JV partner. As a result, they do not reflect the view of the other JV partners. Future research should explore the perspectives of dual or multiple partners (Geringer & Hebert, 1989; Luo et al., 2001; Zhang & Rajagopalan, 2002). Second, other variables that can affect an IJV’s performance include the differences in organizational climates (Fey & Beamish, 2000), cultural similarity (Lin & Germain, 1998), and cooperative goals. These factors should be examined in greater detail. Third, the institutional environment and other variables may influence the choice of a control structure in an IJV. Furthermore, the data collected in this study are limited to those of the IJVs formed in Taiwan. Further research is needed to acquire a more generally applicable model. Finally, the scales used to evaluate an IJV’s performance are subjective, and a different result may be obtained if both subjective and objective scales are used (Geringer & Hebert, 1991). According to Osland and Cavusgil (1996), because using a subjective measure reflects the difficulties of obtaining objective data, future research should use objective indicators to measure the performance of an IJV.

References

Anderson, E., & Gatignon, H. 1986. Modes of foreign entry: A transaction cost analysis and propositions. Journal of International Business Studies, 17(3): 1–26.

Ariño, A. 2003. Measures of strategic alliance performance: An analysis of construct validity. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(1): 66–79.

Baliga, B. R., & Jaeger, A. M. 1984. Multinational corporations: Control systems and delegation issues. Journal of International Business Studies, 15(2): 25–40.

Barden, J. Q., Steensma, K. H., & Lyles, M. A. 2005. The influence of parent control structure on parent conflict in Vietnamese international joint ventures: An organizational justice-based contingency approach. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(2): 156–174.

Barney, J. B. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1): 99–120.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. 1986. Tap your subsidiaries for global reach. Harvard Business Review, 64(6): 87–94.

Beamish, P. W. 1985. The characteristics of joint ventures in developed and developing countries. Columbia Journal of World Business, 20(3): 13–19.

Beamish, P. W., & Banks, J. C. 1987. Equity joint ventures and the theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 18(2): 1–16.

Beamish, P. W., & Lupton, N. C. 2009. Managing joint ventures. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(2): 75–94.

Birkinshaw, J., & Hood, N. 1998. Multinational subsidiary evolution: Capability and charter change in foreign-owned subsidiary companies. Academy of Management Review, 23(4): 773–795.

Blodgett, L. L. 1991. Partner contributions as predictors of equity share in international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 22(1): 63–78.

Burton, F. N., & Saelens, F. H. 1982. Partner choice and linkage characteristics of international joint ventures in Japan: An exploratory analysis of the inorganic chemicals sector. Management International Review, 22(2): 20–29.

Chang, E., & Taylor, S. M. 1999. Control in multinational corporations (MNCs): The case of Korean manufacturing subsidiaries. Journal of Management, 25(4): 541–565.

Chen, D., Park, S. H., & Newburry, W. 2009. Parent contribution and organizational control in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 30(11): 1133–1156.

Child, J., & Faulkner, D. 1998. Strategies of co-operation: Managing alliances, networks, and joint ventures. New York: Oxford University Press.

Choi, C.-B., & Beamish, P. W. 2004. Split management control and international joint venture performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(1): 201–215.

Cullen, J. B., Johnson, J. L., & Sakano, T. 1995. Japanese and local partner commitment to IJVs: Psychological consequences of outcomes and investments in the IJV relationship. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(1): 91–115.

Das, K. T., & Teng, B.-S. 1998. Resource and risk management in the strategic alliance making process. Journal of Management, 24(1): 21–42.

Das, K. T., & Teng, B.-S. 2000a. Instabilities of strategic alliances: An internal tension perspective. Organization Science, 11(1): 77–101.

Das, K. T., & Teng, B.-S. 2000b. A resource-based theory of strategic alliances. Journal of Management, 26(1): 31–61.

Dhanaraj, C., Lyles, M. A., Steensma, H. K., & Tihanyi, L. 2004. Managing tacit and explicit knowledge transfer in IJVs: The role of relational embeddedness and the impact on performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5): 428–442.

Ding, D. Z. 1997. Control, conflict, and performance: A study of U.S.-Chinese joint ventures. Journal of International Marketing, 5(3): 31–45.

Doz, Y., & Prahalad, C. K. 1984. Patterns of strategic control within multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 15(2): 55–72.

Edström, A., & Galbraith, J. R. 1997. Transfer of managers as a coordination and control strategy in multinational organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(2): 248–263.

Fey, C. F., & Beamish, P. W. 2000. Joint venture conflict: The case of Russian international joint ventures. International Business Review, 9(2): 139–162.

Geringer, M. J., & Hebert, L. 1989. Control and performance in international joint venture. Journal of International Business Studies, 20(2): 235–254.

Geringer, M. J., & Hebert, L. 1991. Measuring performance of international joint venture. Journal of International Business Studies, 22(2): 249–262.

Glaister, K. W., & Buckley, P. J. 1998. Management-performance relationships in UK joint venture. International Business Review, 7(3): 235–257.

Glaister, K. W., Husan, R., & Buckley, P. J. 2003. Learning to manage international joint ventures. International Business Review, 12(1): 83–108.

Groot, T. L. C. M., & Merchant, K. A. 2000. Control of international joint ventures. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25(6): 579–607.

Gulati, R., & Singh, H. 1998. The architecture of cooperation: Managing coordination costs and appropriation concerns in strategic alliances. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(4): 781–814.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. 1998. Multivariate data analysis with readings. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Press.

Hamel, G. 1991. Competition for competence and inter-partner learning within international strategic alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 12(4): 83–103.

Harrigan, K. R. 1988. Joint ventures and competitive strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 9(2): 361–374.

Hill, R. C. 1988. Joint venture strategy formulation and implementation: A contingency approach. PhD dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas.

Inkpen, A. C. 2000. Learning through joint venture: A framework of knowledge acquisition. Journal of Management Studies, 37(7): 1019–1043.

Inkpen, A. C. 2008. Knowledge transfer and international joint ventures: The case of NUMMI and General Motors. Strategic Management Journal, 29(4): 447–453.

Inkpen, A. C., & Beamish, P. W. 1997. Knowledge, bargaining power, and the instability of international joint ventures. Academy of Management Review, 22(1): 177–202.

Kale, P., Singh, H., & Perlmutter, H. 2000. Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3): 217–231.

Khanna, T., Gulati, R., & Nohria, N. 1998. The dynamics of learning alliances: Competition, cooperation, and relative scope. Strategic Management Journal, 9(3): 193–210.

Kilduff, M. 1992. Performance and interaction routines in multinational organizations. Journal of International Business Studies, 23(1): 133–145.

Kogut, B. 1988. A study of the life cycle of joint ventures. In F. Contractor & P. Lorange (Eds.). Cooperative strategies in international business: 169–185. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books Press.

Larsson, R., Bengtsson, L., Henriksson, K., & Sparks, J. 1998. The interorganizational learning dilemma: Collective knowledge development in strategic alliances. Organization Science, 9(3): 285–305.

Lecraw, D. J. 1984. Bargaining power, ownership, and profitability of transnational corporations in developing countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 15(1): 27–43.

Li, J., Zhou, C., & Zajac, E. J. 2009. Control, collaboration, and productivity in international joint ventures: Theory and evidence. Strategic Management Journal, 30(8): 865–884.

Lin, X., & Germain, R. 1998. Sustaining satisfactory joint venture relationships: The role of conflict resolution strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1): 179–196.

Luo, Y. 1999. Dimensions of knowledge: Comparing Asian and Western MNEs in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 16(1): 75–93.

Luo, Y. 2001. Determinants of entry in an emerging economy: A multilevel approach. Journal of Management Studies, 38(3): 443–472.

Luo, Y., & Park, S. H. 2004. Multiparty cooperation and performance in international equity joint venture. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(1): 142–160.

Luo, Y., Shenkar, O., & Nyaw, M. K. 2001. A dual parent perspective on control and performance in international joint venture: Lessons from a developing economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1): 41–58.

Lyles, M. A., & Salk, J. E. 1996. Knowledge acquisition from foreign parents in international joint ventures: An empirical examination in the Hungarian context. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5): 877–903.

Madhok, A. 1997. Cost, value and foreign market entry mode: The transaction and the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 18(1): 39–61.

Makhija, M. V., & Ganesh, U. 1997. Control and partner learning in learning-related joint ventures. Organization Science, 8(5): 508–527.

Martinez, Z. L., & Ricks, D. A. 1989. Multinational parent companies’ influence over human resource decision of affiliates: US firms in Mexico. Journal of International Business Studies, 18(3): 465–487.

Meschi, P.-X. 2009. Government corruption and foreign stakes in international joint ventures in emerging economies. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(2): 241–261.

Mjoen, H., & Tallman, S. 1997. Control and performance in international joint ventures. Organization Science, 8(3): 257–274.

Nobel, R., & Birkinshaw, J. 1998. Innovation in multinational corporations: Control and communication patterns in international R&D operations. Strategic Management Journal, 19(5): 479–496.

Ocasio, W. 1997. Towards an attention-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 18(S1): 187–206.

Osland, G. E., & Cavusgil, S. T. 1996. Performance issues in U.S.-China joint ventures. California Management Review, 38(2): 106–130.

Oxley, J. E. 1997. Appropriability hazards and governance in strategic alliances: A transaction cost approach. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 13(2): 387–409.

Oxley, J. E., & Sampson, R. C. 2004. The scope and governance of international R&D alliances. Strategic Management Journal, 25(8): 723–749.

Park, B. I. 2010. What matters to managerial knowledge acquisition in international joint ventures? High knowledge acquirers versus low knowledge acquirers. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 27(1): 55–79.

Park, S. H. & Russo, M. V. 1996. When competition eclipses cooperation: An event history analysis of joint venture failure. Management Science, 42(6): 875–890

Pearce, R. J. 1997. Toward understanding joint venture performance and survival: A bargaining and influence approach to transaction cost theory. Academy of Management Review, 22(1): 203–225.

Pearce, R. J. 2001. Looking inside the joint venture to help understand the link between inter-parent cooperation and performance. Journal of Management Studies, 38(4): 557–582.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5): 879–903.

Simonin, B. L. 2004. An empirical investigation of the process of knowledge transfer in international strategic alliances. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5): 407–427.

Steensma, K. H., & Lyles, M. A. 2000. Explaining IJV survival in a transitional economy through social exchange and knowledge-based perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 21(8): 831–851.

Teramoto, Y., Richter, F.-J., & Iwasaki, N. 1993. Learning to succeed: What European firms can learn from Japanese approaches to strategic alliances. Creativity and Innovation Management, 2(2): 114–121.

Tsang, E. W. K. 1999. A preliminary typology of learning in international strategic alliances. Journal of World Business, 34(3): 211–229.

Tsang, E. W. K. 2000. Transaction cost and resource-based explanations of joint ventures: A comparison and synthesis. Organization Studies, 21(1): 215–242.

Tsang, E. W. K. 2002. Acquiring knowledge by foreign partners from international joint ventures in a transition economy: Learning-by-doing and learning myopia. Strategic Management Journal, 23(9): 835–854.

Wen, S. H., & Chuang, C.-M. 2010. To teach or to compete? A strategic dilemma of knowledge owners in international alliances. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 27(4): 697–726.

Wernerfelt, B. 1984. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2): 171–180.

Williamson, O. E. 1985. The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. New York: Free Press.

Woodcock, C. P., Beamish, P. W., & Makino, S. 1994. Ownership-based entry mode strategies and international performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 25(2): 253–273.

Yan, A., & Gray, B. 1994. Bargaining power, management control, and performance in U.S.-China joint ventures: A comparative case study. Academy of Management Journal, 37(6): 478–517.

Yan, A., & Gray, B. 2001a. Negotiating control and achieving performance in international joint ventures: A conceptual model. Journal of International Management, 7(4): 295–315.

Yan, A., & Gray, B. 2001b. Antecedents and effects of parent control in international joint ventures. Journal of Management Studies, 38(3): 393–416.

Yan, A., & Luo, Y. 2001. International joint ventures: Theory and practice. New York: M.E. Sharpe Press.

Yan, Y., & Child, J. 2004a. Investor’s resource commitments and information reporting systems: Control in international joint venture. Journal of Business Research, 57(4): 361–371.

Yan, Y., & Child, J. 2004b. Investors’ resources and management participation in international joint ventures: A control perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 21(3): 287–304.

Zeng, M., & Chen, X.-P. 2003. Achieving cooperation in multiparty alliances: A social dilemma approach to partnership management. Academy of Management Review, 28(4): 587–605.

Zhang, Y., & Rajagopalan, N. 2002. Inter-partner credible threat in international joint ventures: An infinitely repeated prisoner’s dilemma model. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3): 457–478.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors thank Professor Eric W. K. Tsang, Senior Editor of the Asia Pacific Journal of Management, and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive remarks and helpful feedback.

Appendix 1 Survey items used to measure constructs

Appendix 1 Survey items used to measure constructs

Resource contribution

The scores 1 to 7 have the following denotations: ‘‘1’’—all resources and capabilities in the mentioned item are provided by your partner; ‘‘2’’—most of the resources in an IJV are provided by your partner; ‘‘3’’—your partner contributes slightly more resources than you; ‘‘4’’—the parties contribute an equal amount of resources; ‘‘5’’—you provide slightly more resources than your partner; ‘‘6’’—you provide most of the resources; and ‘‘7’’—you provide all of the resources.

-

(1)

Knowledge of production management

-

(2)

Knowledge of quality assurance

-

(3)

Knowledge of factory layouts

-

(4)

Knowledge of pricing setting

-

(5)

Knowledge of establishing sales channels

-

(6)

Knowledge of promotional activities

-

(7)

Knowledge of making or selling products

-

(8)

General financing capabilities

-

(9)

Long- and medium-term financing

-

(10)

Financial planning capabilities

-

(11)

R&D capabilities for new products

-

(12)

R&D capabilities for production

-

(13)

Knowledge of human resource planning

-

(14)

Top management personnel (e.g., DB, GM, VP, and CEO)

-

(15)

Mid-management personnel (e.g., department managers and plant managers)

Learning intent

How important are the following to your parent company when setting up the joint venture? ‘‘1’’—very unimportant to ‘‘7’’—very important.

-

(1)

To learn production technology from the partner

-

(2)

To learn marketing know-how from the partner

-

(3)

To learn knowledge of finance management from the partner

-

(4)

To learn R&D know-how for new products from the partner

-

(5)

To learn how to create an HR system from the partner

Management control

This part is divided into two sections:

-

(a)

How important is it for your parent firm to control the following activities? The scale scores range from 1 to 7 (‘‘1’’—very unimportant to ‘‘7’’—very important).

-

(b)

What degree of control does your parent firm have over the following activities? The scale scores range from 1 to 7 (‘‘1’’—no control at all and ‘‘7’’—completely control).

-

(1)

Making decisions about production management

-

(2)

Making decisions about QC activities during production management

-

(3)

Making decisions about factory layouts and equipment

-

(4)

Making decisions about pricing strategies

-

(5)

Making decisions about the construction of sales channels

-

(6)

Making decisions about product promotion

-

(7)

Making decisions about general financing

-

(8)

Making decisions about long- and medium-term financing

-

(9)

Making decisions about financing planning

-

(10)

Making decisions about R&D activities on new products

-

(11)

Making decisions about R&D activities on production

-

(12)

Making decisions about human resources planning

IJV performance

Is your parent firm satisfied with the achievements in the following areas? The scale scores range from 1 to 7 (‘‘1’’—very unsatisfied to ‘‘7’’—very satisfied).

-

(1)

The achievements and progress of the joint venture

-

(2)

The cooperative relationship with the partner

-

(3)

The continued cooperation with the partner

-

(4)

The satisfaction with this cooperation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article