Abstract

This study examines a relatively unexplored impression management tactic—supplication. Compared to other more popular impression management tactics such as ingratiation and self-promotion, we know relatively little regarding how employee supplication affects job performance. Using social role theory, we argued that when the images of Chinese employees were consistent with their social roles of receiving help, supplication would be viewed as acceptable. We tested our hypotheses among 158 supervisor–subordinate dyads in China and found that female and junior employees did not receive negative job performance ratings due to supplication. Age, on the other hand, did not moderate the supplication–performance relationship. We believe our findings are consistent with the social norms in the five cardinal relations of Confucianism regarding the modest role of certain social classes in enhancing social harmony. We discuss how our research contributes to the literature of impression management and impacts management practices in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Among the impression management tactics, supplication is the only strategy that exploits one’s weakness in order to achieve the desirable self-image of a needy person. Supplication is also the only impression management attempt that directly obscures the organization’s ability to reach its full workforce capacity. It is opposite to self-promotion, in which attribution of competence is the sought-after impression. Supplication is also drastically different from intimidation, where a person wants to communicate that he/she has the ability to inflict pain or stress on others. Despite the unique characteristics of supplication, it receives far less research attention compared to other more popular impression management tactics, such as ingratiation, exemplification, and self-promotion (Crane & Crane, 2002; Harris, Kacmar, Zivnuska, & Shaw, 2007; Turnley & Bolino, 2001). These impression management tactics (ingratiation, exemplification, self-promotion) communicate the admired images of power and liking, representing “a strong, respected, and considerable individual” (Schlenker, 1980: 287). It is therefore not surprising that most research of impression management focuses on these tactics. The opposite of the impression management spectrum describes images that are not so desirable. Supplication in particular is associated with the image of a powerless, submissive, and weak individual (Schlenker, 1980). Among the few empirical studies of supplication, Gove, Hughes, and Geerkin (1980) found that individuals using supplication were more likely to be alienated and to have poor mental health, low self-esteem, and unhappiness. In general, there is a lack of understanding of how the supplicants are perceived by others in the workplace (Turnley & Bolino, 2001).

Supplication is a tactic to advertise “one’s dependence to solicit help...by stressing his inability to fend for himself or emphasizing his dependence of others” (Jones & Pittman, 1982: 247). The individual engaging in supplication purposely advertises his or her own weaknesses and incompetence so as to gain sympathy from potential helpers (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). As a “norm of obligation or social responsibility,” the helper exerts his/her energy and resources in order to aid the supplicant to survive and to achieve (Jones & Pittman, 1982: 247). In other words, the supplicant is able to convince the helper that without his/her aid, the supplicant will stand little chance of accomplishment. Supplicants achieve their purpose by exaggerating their ineptitude or by extending gratitude to their helper. For the helper, the primary motivation is to acknowledge his/her superiority over the supplicant, a situation not uncommon in the animal world, such as the hierarchical relationship between the leader and the followers in a pack of wolves (Jones & Pittman, 1982). In the work context, an individual supplicates with the intention to avoid a distasteful chore and in an attempt to pass the task to the sympathetic others. Consequently, while the supplicant is relieved of the unpleasant task at hand, the member extending a helping hand actually performs organizational citizenship behavior at the expense of his or her own task performance. Therefore, supplication can be viewed as negative externalities within organizations, the same way as Chen and Chen (2009) interpreted guanxi as a strategy where guanxi parties’ gain could be the organization’s loss.

Supplication is a risky impression management strategy. If successful, the supplicant is able to project an image of needing help. If the tactic is not done carefully, others may see the supplicant as lazy, or not willing to do any work. Jones and Pittman (1982: 248) in particular argued that “there is always the good possibility that the resource-laden person is insensitive to the social responsibility norm.” If the supplicant does not conform to the norm of where social responsibility should be extended (e.g., an affluent individual claiming a lack of money or a well-built male expressing his inability to carry heavy furniture), he or she will run the risk of carrying the negative image of supplication. Our research question therefore is to explore under what conditions supplicants are able to solicit the necessary help. Specifically, we are interested in finding out when the negative image of laziness will be rectified because supplicants are able to convince the helpers that they really need help. Literature on social influence has documented a few instances in which individuals are more likely to obtain help when in need—for example, when the individual seeking help is physically attractive, when there is similarity between the helper and the help seeker, etc. (Cialdini, 2009). In this study, we focus on the demographic characteristics of the supplicants. We argue that the norm of social responsibility to help will be evoked if the images of supplicants are consistent with their social roles of needing help in the Chinese context.

China provides an ideal environment within which to investigate how supplication will be perceived in the work context. First, guided by the five cardinal relations (wŭ lún) of Confucianism (Bond, 1992), Chinese culture emphasizes male-domination in which the male is higher in the social hierarchy than the female is. Despite the remarkable social and cultural changes brought about by the rapid industrialization and modernization process, many Chinese still adhere to these traditional values (Hofstede, 1991). In such context, certain degrees of supplication may be deemed acceptable during work, especially if male domination can be demonstrated. Second, besides male-domination, Chinese culture is also both paternalistic and collectivistic (Hofstede, 1991). As a result, there is a social norm for needy persons to be helped by someone who is more senior in the company. Third, Chinese culture has placed great emphasis on modesty such that supplication may be viewed positively. In a survey of Chinese values, humbleness and moderation were identified as two of the important Chinese values (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987). Humility is seen as a positive virtue among the Chinese because exaggerated claims of ability (such as self-promotion) are generally viewed with suspicion and are considered arrogant. As an opposite of self-promotion, supplication may be interpreted as humility on the surface (Sosik & Jung, 2003) and therefore may be considered acceptable in the Chinese work context.

To examine supplication and job performance, first, we introduce the theoretical background and review of the impression management literature, and show why supplication is among the least studied impression management tactics. Second, using social role theory, we examine the moderating roles of gender, work tenure, and age on the relationship between employee supplication and job performance in China. Finally, we analyze these hypothesized relationships using a matched sample of 158 supervisor–subordinate dyads of three automotive dealers in China to explain how our findings contribute to research on impression management.

Theoretical background

Impression management is the process by which individuals present themselves to appear as they wish others to see them (Rosenfeld, Giacalone, & Riordan, 1995). It results in particular behaviors that influence or manipulate how individuals are perceived, evaluated, and treated with an ultimate purpose of attaining some valued goals (Goffman, 1959; Villanova & Bernardin, 1989). Empirical findings have shown that certain impression management tactics can have an impact on individual outcomes, such as promotions, performance appraisal ratings, and career success (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). For example, ingratiation was positively related to supervisor liking, performance ratings (Wayne & Ferris, 1990), and career success (Judge & Bretz, 1994). Therefore, in most circumstances, individuals intuitively behave in ways that will create positive impressions. Nevertheless, the literature has suggested that individuals may also attempt to appear incapable in order to limit others’ expectations of them (e.g., Braginsky, Braginsky, & Ring, 1969; Schlenker, 1980). For example, Kowalski and Leary (1980) found that individuals depreciated themselves or presented themselves less positively in order to avoid unwanted tasks. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for individuals to attempt to look bad in the first place so that they will look good in the future when exceeding the managed expectation (Becker & Martin, 1995). Jones and Pittman (1982) referred to this phenomenon as supplication whereby individuals broadcast their weaknesses or limitations so as to solicit help from the target person and set up subsequent improvement. By emphasizing his/her incompetence and dependence on others, the supplicant takes advantage of the social rule known as the “social responsibility norm” in which one is obligated to help others in need (Berkowitz & Daniels, 1963). Other concepts such as “deceiving down,” “faking bad,” “playing dumb,” etc., have been used by social psychologists to describe similar behaviors (Becker & Martin, 1995). Regardless of the terms used, there has been a paucity of empirical work on supplication’s effects in organizations.

In this context, while some research has been conducted to investigate the relationship between impression management tactics and performance evaluation (Guadagno & Cialdini, 2007), research on supplication has rested upon a far more tenuous empirical basis. Cumulative results of the very few studies on supplication tend to support its negative relationship with performance ratings (Harris et al., 2007). This is largely due to the fact that individuals using impression management strategies might fail to create their intended desired images, and present the undesired ones unintentionally (Jones & Pittman, 1982). In particular, supplicants intending to portray themselves to be seen as needy (desired image) often run the risk of being perceived as lazy (undesired image) on the flipside. In a study with student subjects, Turnley and Bolino (2001) reported that individuals who used supplication were more likely to be perceived as lazy regardless of their self-monitoring abilities. In today’s organizations where teamwork is a commonplace, human resource flexibility is highly emphasized (Bhattacharya, Gibson, & Doty, 2005). In such circumstances, supplicants demonstrating their skill or behavior inflexibility may be seen as a liability for organizations, and thus may be perceived negatively. For example, Harris and his colleagues (2007) found that the main effect of supplication was negatively related to job performance. Furthermore, in explaining why supplication failed, Jones and Pittman (1982) described the possibility that persons targeted by supplicants were simply insensitive to the social responsibility norm upon which supplicants relied. As a result, supplication is a precarious impression management strategy where supplicants place themselves in a vulnerable position of falling into disfavor, and eventually can suffer the dire consequence of not receiving any support to accomplish the task (Gardner, 1992). Thus, theory and empirical evidence suggests a negative relationship between supplication and job performance.

Hypothesis 1

Employee supplication will be negatively related to job performance.

Gender as a moderator

The social role theory of gender differences suggests that men and women are raised to behave according to their gender roles in society (Eagly, 1987) and this may affect supplication. Men are expected to adopt masculine roles such as dominance, aggression, and achievement, whereas women are expected to take feminine roles such as affiliation, nurturance, deference, and abasement (Watson & Hoffman, 2004). With a female labor force participation rate of 68% (compared to 83.9% in Iceland, a country high in femininity, OECD, 2004), China has made such gender role differences more visible. Traditional Chinese values advocate the concept of the male as the breadwinner, and the female as the caregiver, such that a man’s primary responsibility is at work whereas a woman’s duties are child-rearing and home-making (Chow, 1995). Although married women may work nowadays, they are generally not the primary source of income in the family. Social role theory predicts that any violation from the normative expectations based on gender roles is likely to be perceived negatively. Therefore, women tend to avoid tasks which are considered masculine in order to behave in ways consistent with their social roles. This tendency is expected to be augmented in the context of China where rigid adherence to the traditional gender roles is particularly prominent.

The implication of social role theory for impression management is that men and women are viewed differently when they engage in the same tactic. For example, the use of ingratiation was found to be positively related to performance evaluations for women only because making oneself likeable was a feminine characteristic (Kipnis & Schmidt, 1988). Similarly, in a study of the use of self-promotion (a masculine-appropriate behavior) by women, Rudman (1998) explained a phenomenon called “the backlash effect.” She found that women who actively highlighted their success were interpreted as violating their gender role prescriptions. Since such self-promotion was not gender appropriate for females, they were likely to be penalized in terms of salary and promotion. Following this logic, a man who supplicates may be perceived as violating the gender norm of masculinity. Advertising one’s own weaknesses and declaring dependence on others are more in line with the normative expectations of the feminine rather than masculine roles. Likewise, supplication by a woman is likely to be viewed as a legitimate feminine behavior consistent with the gender norm. In the original work of impression management, Jones and Pittman (1982) also used gender to describe why supplication at traditionally masculine tasks was seen to be acceptable when a female was paired with a male in facing the physical world. For example, a classic female supplicant could easily solicit help from a classic male counterpart by expressing incompetence at changing a tire, understanding algebra, or carrying heavy objects, etc. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2

Gender will moderate the relationship between supplication and job performance, such that the relationship will be less negative for women than for men.

Tenure as a moderator

Work tenure is a reflection of experience and knowledge in the organization (Lau, Lam, & Salamon, 2008). As an individual’s career unfolds in a company, his or her job knowledge, skills, abilities, and confidence increase. Moreover, work tenure enhances one’s understanding of organizational culture, policies and procedures, and the way tasks should be accomplished (Zenger & Lawrence, 1989). As a result, high-tenured employees are considered to be senior, more experienced, and resource-laden. By contrast, low-tenured employees often lack the experience and resources which are essential to effective performance in organizations. As discussed previously, the social responsibility norm suggests the obligation for the resource-laden individuals, when being solicited for help, to provide assistance to those who lack or think they lack the resources. Consistent with the social role theory, the normative expectation of helping others in need should therefore be stronger for high-tenured employees than low-tenured ones. This is particularly applicable in China’s paternalistic society, in which a senior leader is expected to take care of the junior staff and to assume a nurturing role in the organization. Furthermore, high-tenured employees should carry themselves in a competent manner and serve as role models for others (Moser & Galais, 2007). As a result, supplication strategy adopted by high-tenured employees can represent a major discrepancy from the normative expectations based on seniority, and therefore, will be more negatively evaluated; the same strategy used by low-tenured employees is consistent with the normative expectation, thus is seen as legitimate and will be perceived less negatively. Furthermore, supervisors have longer previous work records when assigning job performance ratings for high-tenured employees. This means high-tenured employees will have increasing difficulties in getting away with supplication (Moser, Schuler, & Funke, 1999). Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Tenure will moderate the relationship between supplication and job performance, such that the relationship will be less negative for low-tenured than high-tenured employees.

Age as a moderator

Age represents wisdom and respect. Such representation is more intense in the context of China because another essence of traditional Chinese culture is the emphasis on the respect for elders (Luo, 2000; Tsui & Farh, 1997). Confucius advocated loyalty and reciprocity in the five cardinal relationships in society. Age and hierarchy are respected in each of these five basic relationships so that the younger one has to show respect for authority and obedience to the elder one. In return, the elder one is expected to protect and take care of the younger one. Among the very few studies of impression management exploring the effects of age, Gove and his colleagues (1980) reported that younger employees were more likely to use the supplication tactic than older ones. Gardner (1992) accounted for this observation with the lower status roles occupied by young employees, so that supplication was considered legitimate for them. We expect that this justification fits more strongly in China because of the implied hierarchy inherent in age, such that elder employees have higher status roles than younger employees do. This argument is also consistent with the normative expectations prevailing in China that elder employees are expected to behave as resourceful individuals and provide help to younger employees, whereas younger employees are expected to be loyal to and protected by the elders. Therefore, in the context of China, supplication tactics adopted by elder employees are likely to be seen as violating the normative expectations, and be evaluated more negatively, while younger employees employing the same tactics are likely to be accepted and thus perceived less negatively. As a result, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Age will moderate the relationship between supplication and job performance, such that the relationship will be less negative for young employees than old employees.

Materials and methods

Sample and data collection procedures

Employees from three automotive dealers in a major city in China were invited to participate in this study. All three dealers sold the same French brand of automobiles and had similar organizational structures—sales, after-sales (repair, maintenance, and parts), human resources, and accounting. One of the authors travelled to the three dealers and collected the data on-site. The purpose of this research was explained to the employees before they completed the survey. Two local news summaries were also included in the survey. Employees were told that if they were unwilling to take part in this study, they could read the news summaries during the survey and return the blank questionnaires afterwards. Among the 184 questionnaires distributed, 158 were returned with useful responses (approximately 86%). There were 47 useful questionnaires out of 54 in the first dealer, 48 out of 61 in the second, and 63 out of 69 in the third. 101 of the respondents were men (63.9%) and 57 were women (36.1%). About 50% of the respondents worked for more than 1 year in their store. Approximately 93.7% of the respondents were 35 years old or younger.

Measures

Supplication

We used Bolino and Turnley’s (1999) 5-item scale to measure how often employees would use the supplication tactic at work. Sample items included “act like you know less than you really do so that other group members will help you out” and “try to gain assistance or sympathy from other group members by appearing needy in some area.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.824.

Job performance

We asked supervisors to rate employee’s job performance in terms of task performance and supervisor’s expected performance. First, an employee’s task performance was measured using the seven-item scales from Williams and Anderson (1991). Sample items were “this employee adequately completes assigned duties” and “this employee fulfills responsibilities specified in the job description.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.792.

Second, we followed Wayne, Liden, Graf, and Ferris’s (1997) approach to measure supervisor’s expected performance for each employee in addition to his/her task performance. The six items of supervisor’s expected performance were adopted from Harris and his co-authors (2007). Sample items included: “overall, to what extent has this employee been performing his/her job the way you would like it to be performed?” and “if you entirely had your way, to what extent would you change the manner in which this employee is performing his/her job?” (reverse coded). The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.807.

Gender, tenure, education, and age

In the survey, each employee also reported gender, work tenure, level of education, and age. Gender was stated as a dummy variable (0 = male; 1 = female). Work tenure was measured in a five-point scale (1 = 6 months or below; 5 = 3 years or above), level of education was anchored to a six-point scale ranging from high level (1) to low level (6), whereas age was measured in an eight-point scale (1 = 20 or below; 8 = 50 or above).

Data analysis

In this study, supervisors provided the ratings of job performance for more than one subordinate. To control for nonindependence effects at supervisor-level, hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was employed with the average supervisor’s evaluation of his/her subordinates’ job performance as a level-2 control in all analyses. HLM allows simultaneous investigation of relationships within and between levels. First, we ran a null model (without independent variables) to test if there were significant between-group differences in performance ratings. This null model is equivalent to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A presence of significant between-group differences among groups supports the assumption that supervisors’ levels of leniency in assigning ratings were different across groups. Second, random coefficient regression models were constructed to examine the level-1 relationships between supplication and job performance ratings.

Results

Table 1 reports the means, standard deviations, and correlations for all variables in the analyses. The HLM results are presented in Table 2. The null model shows that there was systematic between-group variance in task performance (χ2(39) = 174.06; p < 0.000) and supervisor’s expected performance (χ2(39) = 79.25; p < 0.000). Following the procedure suggested by Hofmann, Griffin, and Gavin (2000), an intra-class correlation (ICC) was computed. The ICC indicates that 49% of the variance in task performance resided between supervisors, while 51% of the variance resided within supervisors. For supervisor’s expected performance, 21.5% of the variance resided between supervisors, while 78.5% resided within supervisors. Therefore, these figures indicate the need to control for supervisor-level effects.

Before testing the hypotheses, a random coefficient regression model was estimated for the control variables, i.e., age, gender, education, tenure, and the level-2 average of supervisor’s ratings. The HLM results in Table 2 show that the level-2 supervisor’s control consistently predicted both task performance and supervisor’s expected performance. Apart from the level-2 supervisor control, as shown in Models 1 and 6, tenure positively predicted task performance and supervisor’s expected performance. On the other hand, age was negatively related to supervisor’s expected performance.

To test the hypotheses in this study, a random coefficient regression model was conducted for task performance and supervisor’s expected performance separately. Hypothesis 1 predicted a negative relationship between supplication and performance ratings. According to Models 2 and 7, supplication was significantly related to task performance (γ = −0.07, p < 0.01) and supervisor’s expected performance (γ = −0.05, p < 0.05) in the hypothesized direction, thus providing strong support for Hypothesis 1.

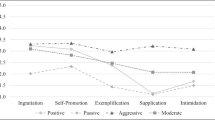

Hypothesis 2 predicted that gender would moderate the relationship between supplication and performance ratings. Models 3 and 8 reveal that the interaction of supplication with gender (0 = male; 1 = female) was a significant predictor of task performance (γ = 0.12, p < 0.05) only, but not supervisor’s expected performance (γ = 0.02, ns). From these results, we calculated that the interaction term explained 5% (ΔR2) of the residual level-1 variance. Further examination of the interaction effects indicated that the negative relationship between supplication and task performance was stronger for men than for women. Figure 1 illustrates these findings. In particular, the flat slope for women indicates that women’s task performance was not affected by their levels of supplication. As a result, the significance of the γ parameter together with the form of interaction provided support for the prediction of task performance in Hypothesis 2.

The test of Hypothesis 3 is shown in Models 4 and 9. Results indicate that the interaction of supplication and tenure was significant in predicting supervisor’s expected performance (γ = −0.04, p < 0.05) only, but not task performance (γ = 0.03, ns). The explained variance by this interaction was 1%. The plot in Figure 2 shows that the form of interaction was consistent with the hypothesized direction, such that the negative relationship was stronger for high-tenured employees than low-tenured. Specifically, supplication was negatively related to supervisor’s expected performance for high-tenured employees but the relationship was not significant for low-tenured employees, i.e., low-tenured employees received roughly the same rating regardless of their levels of supplication. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 received partial support.

Similarly, Models 5 and 10 show the results of Hypothesis 4, testing the moderating effect of age. The interaction of supplication and age was not significant for both task performance (γ = 0.03, ns) and supervisor’s expected performance (γ = 0.01, ns). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was not supported.

Discussion

Our paper examines the relationship between employee supplication and job performance in the Chinese context. Among the impression management tactics proposed by Jones and Pittman (1982), research on supplication is few and far between. The few studies conducted on supplication indicate that in general supplicants are more likely to portray lazy (negative) rather than needy (positive) images. Thus their job performance will suffer afterwards. Social role theory on the other hand suggests that if the social image of supplicants is consistent with the ones that need help, supplicants will be able to solicit aid from the helpers due to the social norm of responsibility. Most importantly, with the proper social image, supplicants reduce the risk to be perceived as lazy employees. We tested our proposed relations in China because certain Chinese cultural values allow supplication to be deemed acceptable. Chinese culture advocates ordering relationships by status, such that one class of people will be submissive in front of another class (zūn bēi yŏu xừ) (The Chinese Culture Connection, 1987). To enhance social order and harmony, the five cardinal relations of Confucianism establish the role of certain social groups and their inter-group relationships (Bond, 1992). Thus it is highly proper for the female and the junior employees to be modest in the workplace, and to receive guidance and help from the male and the more senior staff.

Our findings are consistent with previous research that supplication is negatively related to job performance. However, our analyses also show that female and low-tenured employees were able to supplicate and to receive not-so-negative job performance ratings. The moderating role of gender and work tenure was consistent with our prediction that certain supplication tactics were acceptable in China because of inherent cultural values emphasizing social harmony and hierarchy.

Some of our results are worthy of further interpretation. First, the moderating role of gender found support in task performance but not in supervisor’s expected performance, whereas the opposite was observed for the moderating role of work tenure. Task performance is a function of how well employees perform their prescribed roles according to the job description. For the same job, male employees are expected to perform better than their female colleagues, especially in the Chinese society where masculinity is emphasized. Thus supplication by female employees was considered to be normal and would not affect their task performance, as seen in Figure 1. On the other hand, low-tenured and high-tenured employees are likely to occupy different jobs. Because the prescribed roles of low-tenured employees are already different, and most likely less demanding, when compared to high-tenured employees, supplication by low-tenured employees was considered unacceptable. Regarding our findings on the supervisor’s expected performance, it is plausible that compared with male subordinates, supervisors already had different expectations for their female subordinates (Lockheed & Hall, 1976). Therefore additional supplication by female workers may further deteriorate their performance evaluation. As a result, gender did not moderate the relationship between employee supplication and supervisor’s expected performance. On the other hand, since supervisors by default are more senior, they will be more lenient towards low-tenured employees and more likely to consider their supplication acceptable. Thus we observed the flat relationship in Figure 2 regarding supplication and supervisor’s expected performance among low-tenured workers.

Second, we found no support for the moderating role of age. One possibility of our non-findings is due to our sample characteristics, where the majority of workers were 35 years old or younger. To give a fair test of Hypothesis 4, we would need a sample with more much older (e.g., 50+) employees so that we could analyze if supplication by younger employees could be considered more acceptable than that by the older staff. We will further address this issue under “Directions for future research.” Another explanation involves the indistinguishable age difference especially when the age gap was not wide in our sample. As suggested by one of the reviewers, unlike job title and seniority which can be publicly known and easily distinguished, age information has to be explicitly conveyed by the focal employee. Although supervisors normally have such information in the archive, they might not have good memory or pay close attention to it.

Theoretical contribution

A major theoretical contribution of this study lies in its ability to confirm the relationship of impression management tactics with social identity. Specifically we were able to show that the fit between the image claimed and the stereotypical characteristics of the actor’s social identity is important in determining the outcome of the actor’s impression management tactic. To our knowledge, no previous research has examined the roles of gender and tenure on the use of supplication (c.f., Rudman’s (1998) study on female self-promoters). Our study offers the first empirical support that female and junior employees could employ supplication tactics more effectively than their male and senior counterparts. In other words, some supplicants could actually get away from reprisal depending on who they were. This is an important contribution to the literature on impression management because it suggests the consideration of contextual factors in deploying impression management tactics.

Our findings also further our knowledge regarding how to implement strategic self presentation successfully. In Schlenker’s (1980) seminal book on impression management, the author proposed that the projected self image should match with the image requirements in order to claim it legitimately. What we proposed and demonstrated was that for supplication to be conducted effectively, individuals needed to be mindful on presenting their needy characteristics first. Particularly in the Chinese context, we were able to show that female and low-tenured employees were more able to fulfill requirements of the needy image. Schlenker (1980) further stated that images of the strategic self were more likely to be challenged in longer rather than in briefer encounters. In our study, supplicants with high tenure (having long encounters in the organization) were more susceptible to continual challenges than those with low tenure, resulting in poorer performance evaluation. As Schlenker (1980: 99) put forth, “People who claim to be what they are not will sooner or later fail to meet a challenge, and their façades will crumble, causing embarrassment and possibly negative social sanctions.”

Since social identity is instrumental in effective impression management, and appropriate behaviors arising from a social identity are subject to cultural variation, another contribution of this study is to test the Western developed impression management theory in the context of China. This is the first study focusing on the examination of supplication in China. Her unique cultural values allow this study to take the first step toward the understanding of the intertwining relationships among supplication, modesty, humility, and social-role stereotyping based on gender and seniority. Although supplication and modesty are two distinct constructs, their distinction is often obscured in the eye of the beholder. For example, remarks such as “I can’t do it without you, I count on you for the success of this project” can be interpreted as soliciting help from others as an expression of either supplication or modesty. For example, in a study of perceived impression management strategies employed by world-class transformational leaders, Ronald Reagan, well known for his humility, was ranked the highest in the supplication dimension (Gardner & Cleavenger, 1998). Another study conducted by Sosik and Jung (2003) found that individuals who rated themselves modestly were percieved by some as acts of supplication. When the taxonomy of strategic self presentation was first introduced by Jones and Pittman (1982), little discussion was devoted to how impression management tactics could be conducted in cross-cultural context. Our study thus contributes to Jones and Pittman’s (1982) framework by showing the possibility that modesty and humility, in addition to neediness, can serve as desirable images of supplication.

Managerial contribution

Results of this study also serve practical contributions for both Chinese employees and managers. First, based on these findings, supplicants who strive to maintain a positive impression would benefit from understanding the normative expectations that supervisors place on them. Specifically, male and senior employees should avoid using supplication; otherwise they will be punished more severely for transgressing the social norms.

Second, practicing managers in China also benefit from knowing the potential influences of employees’ demographic characteristics on the accuracy of performance appraisal. Although not directly measured in our study, impression management might be associated with perceived injustice—a relationship which is relatively unexplored. As mentioned, impression management involves manipulating, controlling, and influencing the projected images in order to obtain some valued goals (Goffman, 1959). This study shows that although supervisors normally discounted employees’ performance ratings for supplicating, they were intuitively more lenient to female and junior supplicants. It shows that certain groups of supplicants obtained their valued goal of not putting as much effort on the job while having their performance ratings unaffected. Perceived injustice may be formed among other employees, particularly the non-supplicants, and in turn undermine their contributions and attitudes towards organizations, such as organizational citizenship behaviors, organizational commitment, etc. Furthermore, supervisor’s leniency toward certain supplicants may further reinforce supplicating behaviors in those social groups. Therefore, we suggest that supervisors should not be obliged to offer lenient performance evaluation to supplicants, but instead provide sufficient organizational support and socialization to help needy employees. Both perceived organizational support and procedural justice were found to enhance career satisfaction of Chinese employees (Loi & Ngo, 2008). Given the strong reliance of important personnel decisions on performance evaluation, managers should adopt performance evaluation criteria that are objective, clearly established, and bias-free, and consider using the performance evaluation procedures that are anonymous (e.g., without taking into account the social identity of the employees).

Study limitations

Despite these significant findings, as with any research, this study has several limitations. First, although this study incorporated matched-sample data from subordinates and supervisors, it was a cross-sectional study, thus making causal inferences problematic. In evaluating the findings, we could not conclusively argue whether supplication caused low performance ratings or whether employees adopted supplication tactics in response to low performance ratings. It is well-documented that employees’ confidence in tasks decreases when they receive negative feedback or low performance expectations (Beyer & Bowden, 1997). Future research using longitudinal data will be needed to further explore the nature of the relationships and obtain more veridical results.

Another limitation is the use of employees’ self-reported supplication behavior. Employees were likely to find it undesirable to report the use of supplication tactics, thus causing the assessment of supplication in this study to be less accurate. There is a good possibility that those employees who frequently supplicated were better at managing others’ impressions and, as a result, were not likely to admit that they supplicated in the past. We acknowledge the fact that measuring impression management behavior is always difficult because neither direct observation of the behavior nor supervisor report is a valid method (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). Furthermore, because impression management tactics are often directed at the supervisors, coworkers’ perspectives towards the “actors” are likely to differ from the supervisors’ (Wayne, Kacmar, & Ferris. 1995). Therefore, reliance on self-reported data is still necessary. Nevertheless, findings of this study should be interpreted cautiously in light of the limitation imposed by self-reported data on supplication.

Finally, we intentionally chose a more “masculine” industry, the automobile industry, in order to augment the possible effect of gender stereotyping in understanding the images of supplication projected by men and women. In one way, the chosen industry represents strength in this study. In another way, focusing on only one industry coupled with the small sample size somewhat limits the generalizability of our findings. Therefore, we believe that future research would benefit from investigating the issues of supplication using more diverse subjects drawn from different organizations and industries, particularly in feminine or less gender-biased industries.

Directions for future research

The limitations discussed above have suggested several methodological areas for future investigations to focus on. In addition, the results of this study also leave some potential avenues for future research in understanding supplication. Our findings suggest that employees were penalized for supplication if their supplication behavior violated the normative expectations arising from their own demographic characteristics. However, we focused on one type of impression management strategy only, i.e., supplication. Future research efforts should be made to explore the use of impression management tactics in combination rather than in isolation (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). It is not uncommon that individuals simultaneously use more than one impression management tactic in influencing others. For instance, adopting supplication together with ingratiation might generate better images than supplication paired with intimidation. Prior literature suggests that supplication and self-promotion are in essence opposites (Jones & Pittman, 1982; Rosenfeld et al., 1995), and additional research is also needed to confirm such a relationship empirically. Moreover, although literature has proposed several possible images of supplication, such as needy and lazy (Turnley & Bolino, 2001), other images such as modesty and sense of respect might concurrently exist. Modesty is an important Chinese virtue but there is little work to our knowledge that conceptualizes and operationalizes this indigenous construct. Similarly, sense of respect might also be earned for humble individuals in the Chinese context. Therefore, future research work should be sought for examining the nature of the images presented by supplicants, measuring the perception of recipients, and analyzing which image affects job performance the most.

Another important area for future research is the cross-cultural comparison of the impact of impression management tactics on performance rating. Perception of recipients towards a single impression management tactic can differ across culture. We argue that the difficulty to distinguish between supplication and modesty in the Chinese context might muddle the negative effect of supplication. This argument can be ascertained by replicating our study in a non-Chinese sample where humility is not as heavily emphasized, such as with a North American sample. If our theory is correct, the negative relationship between supplication and performance ratings should be stronger for the North American sample, who are more likely to perceive supplicants as lazy, than for the Chinese, who are more likely to consider supplication a humble virtue.

Possibility of future research also holds in testing exact opposite effects of supplication and self-promotion in the cross-cultural context. Self-promotion is more likely to be seen as hubristic and arrogant, considered as negative images in the Chinese culture, but is often seen positively as assertive and ambitious in the Western context (Gardner, 1992). Ciacalone and Rosenfeld (1986) argued that self-promotion is a stronger characteristic among Americans than Chinese. If researchers in the future include both self-promotion and supplication in the same cross-cultural study, we are then able to analyze if self-promotion and supplication generate opposite results between the Chinese and a North American sample. Doing so will further our understanding of how impression management is manifested in different cultures.

Given the interpersonal nature of impression management behavior, in which actors and audience must be present, the composition of supervisor-subordinate dyads warrants significant attention in future research. As we emphasized previously, Chinese culture highlights observing the social order in the five cardinal relations, particularly between men and women. A male supervisor might feel obligated to help and protect a female subordinate who supplicates, but the same might not be true for a female supervisor who has far less social pressure to protect another female colleague. Senior and high-tenured supervisors are expected to be lenient on their junior and low-tenured subordinates, but the same expectation may not hold if both supervisors and subordinates are of similar tenure and age. On the other hand, relationship between supervisor and the supplicant might be of substance. The effectiveness of supplication is more likely to be enhanced when the supervisor–subordinate relationship is of high quality. Thus future research should examine if demographic composition of supervisor–subordinate dyads and LMX will affect the perception of supplicants by their supervisors.

Lastly, this study focuses only on the moderating role of surface attributes of individual characteristics in determining the effectiveness of supplication tactics. However, it is not certain that these surface attributes will have stable and long-term influences. It might as well be possible that the effects of these surface attributes are compromised and lose their influence after a certain period of time. According to Harrison, Price, and Bell (1998), deep-level attributes were more likely to have enduring influences on work group dynamics than surface-level attributes. Thus, it is imperative for future studies to incorporate longitudinal research designs as well as examine the effects of deep-level attributes, such as the supplicants’ personality, in terms of sociability, and the supplicants’ skills, in terms of political skills, self-monitoring skills, and social skills, etc. (Ferris, Witt, & Hochwarter, 2001; Harris et al., 2007; Turnley & Bolino, 2001).

Conclusion

This study focuses on a relatively less explored dimension of impression management—supplication. The findings show that individuals are punished on their performance evaluation if their supplication tactic transgresses the social role norms. Given the negative impact of supplication on an organization’s productivity, the findings in this study suggest that practicing managers as well as their employees should be aware of the potential influence of stereotyping based on social status norms and the potential impact on the performance appraisal system.

References

Becker, T. E., & Martin, S. L. 1995. Trying to look bad at work: Methods and motives for managing poor impressions in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 174–199.

Berkowitz, L., & Daniels, L. R. 1963. Responsibility and dependency. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66: 664–669.

Beyer, S., & Bowden, E. M. 1997. Gender differences in self-perceptions: Convergent evidence from three measures of accuracy and bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23: 157–172.

Bhattacharya, M., Gibson, D. E., & Doty, D. H. 2005. Human resources and competitive advantage: The effects of skill, behavior and HR practice flexibility on firm performance. Journal of Management, 31: 622–640.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. 1999. Measuring impression management in organizations: A scale development based on the Jones and Pittman taxonomy. Organizational Research Methods, 2: 187–206.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. 2003. Counternormative impression management, likeability, and performance ratings: The use of intimidation in an organizational setting. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24: 237–250.

Bond, M. (Ed.). 1992. The psychology of the Chinese people. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Braginsky, B. M., Braginsky, D. D., & Ring, K. 1969. Methods of madness: The mental hospital as a last resort. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Chen, C. C., & Chen, X.-P. 2009. Negative externalities of close guanxi within organizations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26: 37–53.

The Chinese Culture Connection. 1987. Chinese values and the search for culture-free dimensions of culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18: 143–164.

Chow, I. H. S. 1995. Career aspirations, attitudes and experiences of female managers in Hong Kong. Women in Management Review, 10: 28–32.

Ciacalone, R. A., & Rosenfeld, P. 1986. Self-presentation and self-promotion in an organizational setting. Journal of Social Psychology, 126: 321–326.

Cialdini, R. 2009. Influence: Science and practice, 5th ed. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Crane, E., & Crane, F. G. 2002. Usage and effectiveness of impression management strategies in organizational settings. International Journal of Action Method, 55: 25–34.

Eagly, A. H. 1987. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ferris, G. R., Witt, L. A., & Hochwarter, W. A. 2001. Interaction of social skill and general mental ability on job performance and salary. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86: 1075–1082.

Gardner, W. L. 1992. Lessons in organizational dramaturgy: The art of impression management. Organizational Dynamics, 21: 33–47.

Gardner, W. L., & Cleavenger, D. 1998. The impression management strategies associated with transformational leadership at the world-class level: A psychohistorical assessment. Management Communication Quarterly, 12: 3–38.

Goffman, E. 1959. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday.

Gove, W. R., Hughes, M., & Geerkin, M. R. 1980. Playing dumb: A form of impression management with undesirable side effects. Social Psychology Quarterly, 43: 89–102.

Guadagno, R. E., & Cialdini, R. B. 2007. Gender differences in impression management in organizations: A qualitative review. Sex Roles, 56: 483–494.

Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., Zivnuska, S., & Shaw, J. D. 2007. The impact of political skill on impression management effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92: 278–285.

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., & Bell, M. P. 1998. Beyond relational demography: Time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Academy of Management Journal, 41: 96–107.

Hofmann, D. A., Griffin, M. A., & Gavin, M. B. 2000. The application of hierarchical linear modelling to organizational research. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.). Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: 467–511. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hofstede, G. 1991. Culture and organizations: Software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. 1982. Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. In J. Suls (Ed.). Psychological perspectives on the self, 1: 467–511. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Judge, T. A., & Bretz, R. D. 1994. Political influence behaviour and career success. Journal of Management, 20: 43–65.

Kipnis, D., & Schmidt, S. M. 1988. Upward-influence styles: Relationship with performance evaluation, salary, and stress. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33: 528–542.

Kowalski, R. M., & Leary, M. R. 1980. Strategic self-presentation and the avoidance of aversive events: Antecedents and consequences of self-enhancement and self-depreciation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26: 322–336.

Lau, D. C., Lam, L. W., & Salamon, S. D. 2008. The impact of relational demographics on perceived managerial trustworthiness: Similarity or norms?. Journal of Social Psychology, 148: 187–208.

Lockheed, M. E., & Hall, K. P. 1976. Conceptualizing sex as a status characteristic: Application to leadership training strategies. Journal of Social Issues, 32: 111–124.

Loi, R., & Ngo, H.-Y. 2008. Mobility norms, risk aversion, and career satisfaction of Chinese employees. Asia Pacific Journal of Management doi:10.1007/s10490-008-9119-y.

Luo, Y. 2000. Guanxi and business. Singapore: World Scientific.

Moser, K., & Galais, N. 2007. Self-monitoring and job performance: The moderating role of tenure. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 15: 83–93.

Moser, K., Schuler, H., & Funke, U. 1999. The moderating effect of raters’ opportunities to observe ratees’ job performance on the validity of an assessment center. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 7: 133–141.

OECD. 2004. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. http://www.oecd.org/, Accessed May 10, 2008.

Rosenfeld, P. R., Giacalone, R. A., & Riordan, C. A. 1995. Impression management in organizations: Theory, measurement, and practice. New York: Routledge.

Rudman, L. A. 1998. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74: 629–645.

Schlenker, B. R. 1980. Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Sosik, J. J., & Jung, D. I. 2003. Impression management strategies and performance in information technology consulting: The role of self-other rating agreement on charismatic leadership. Management Communication Quarterly, 17: 233–268.

Tsui, A. S., & Farh, J. L. 1997. Where guanxi matters: Relational demography and guanxi in the Chinese context. Work and Occupations, 24: 56–79.

Turnley, W. H., & Bolino, M. C. 2001. Achieving desired images while avoiding undesired images: Exploring the role of self-monitoring in impression management. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85: 351–360.

Villanova, P., & Bernardin, H. J. 1989. Impression management in the context of performance appraisal. In R. A. Giacalone & P. Rosenfeld (Eds.). Impression management in the organization: 299–313. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Watson, C., & Hoffman, L. R. 2004. The role of task-related behaviour in the emergence of leaders: The dilemma of the informed woman. Group and Organization Management, 29: 659–685.

Wayne, S. J., & Ferris, G. R. 1990. Influence tactics, affect, and exchange quality in supervisor-subordinate interactions: A laboratory experiment and field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75: 487–499.

Wayne, S. J., Kacmar, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. 1995. Coworker responses to others’ ingratiation attempts. Journal of Managerial Issues, 7: 277–289.

Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., Graf, I. K., & Ferris, G. R. 1997. The role of upward influence tactics in human resource decisions. Personnel Psychology, 50: 979–1006.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. 1991. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17: 601–617.

Zenger, T. R., & Lawrence, B. S. 1989. Organizational demography: The differential effects of age and tenure distributions on technical communication. Academy of Management Journal, 32: 353–376.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, J.Y.M., Lam, L.W. & Liu, Y. Do you really need help? A study of employee supplication and job performance in China. Asia Pac J Manag 27, 541–559 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-009-9152-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-009-9152-5