Abstract

Conceptual models of implementation posit contextual factors and their associations with evidence-based practice (EBP) use at multiple levels and suggest these factors exhibit complex cross-level interactions. Little empirical work has examined these interactions, which is critical to advancing causal implementation theory and optimizing implementation strategy design. Mixed effects regression examined cross-level interactions between clinician (knowledge, attitudes) and organizational characteristics (culture, climate) to predict cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic therapy use with youth (N = 247 clinicians across 28 agencies). Results indicated several interactions, highlighting the importance of attending to interactions between variables at multiple levels to advance multilevel implementation theory and strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Identifying factors that predict clinicians’ use of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in mental health settings is important for developing effective implementation strategies to improve the quality of care for those seeking treatment (Proctor et al. 2011). Conceptual models of implementation posit factors influencing clinician practice use at multiple levels (e.g., individual, organizational). Consistent with this, there is an extensive literature examining predictors of clinician practice use documenting main effects of variables across these levels on implementation outcomes in mental health service systems (Becker et al. 2013; Beidas et al. 2015; Brookman-Frazee et al. 2010; Czincz and Romano 2013; Henggeler et al. 2008; Higa-McMillan et al. 2015; Jensen-Doss et al. 2009; Lim et al. 2012; Nelson and Steele 2007). However, how these multilevel factors interact with one another to predict practice use is poorly understood. While many conceptual models imply interactive or synergistic cross-level effects, few speculate the direction or strength of cross-level interactions and therefore lack causal specificity (Damschroder et al. 2009; Tabak et al. 2012; Wandersman et al. 2008). Some frameworks suggest that general and/or innovation-specific organizational context is a necessary foundation for successful implementation to occur (Durlak and DuPre 2008; Powell et al. 2017) and emerging evidence has started to unpack the relationship between these contextual factors (e.g., the relationship between organizational and therapist characteristics; Powell et al. 2017).

While there is a burgeoning literature examining the mechanisms by which organizational processes influence EBP implementation (e.g., Williams et al. 2017). To our knowledge, no empirical work has yet examined how these organizational processes interact with clinician characteristics to predict clinician practice use. Identification of potential mechanisms by which implementation strategies may influence EBP use has been identified as a key step toward advancing the science of implementation (Lewis et al. 2018). Empirical examination of how theorized implementation predictors interact can improve our understanding of the mechanistic processes through which implementation strategies affect practice use, guide selection of targeted implementation and de-implementation strategies, and identify strategic points of intervention. Prior work has established that both organizational and clinician factors influence individual clinician practice use (Beidas et al. 2015; Aarons et al. 2015), although the mechanisms by which these levels interact with one another to influence practice use are poorly understood (Brookman-Frazee and Stahmer 2018; Glisson and Williams 2015; Lewis et al. 2018). Elucidating cross-level predictive pathways in the context of EBP implementation efforts can inform our understanding of these cross-level mechanisms that influence clinician uptake of EBPs, which in turn can inform the development of implementation strategies to target these causal pathways.

Building on work examining the relative contributions of clinician and organizational variables as predictors of clinician practice use in the publicly-funded Philadelphia mental health system (Beidas et al. 2015; Powell et al. 2017), we expand this prior work to examine the interactive processes across these factors that influence clinician practice. We aim to highlight the importance of specifying and testing cross-level interactions at the two levels most proximal to implementation—the clinician and the organization- (Damschroder et al. 2009). We then draw out implications of these interactions to begin to unpack how therapist-level variables moderate the influence of organizational culture and climate on practice use. Recent work has highlighted the importance of considering such boundary conditions of organizational influences (i.e., the “who, where, when” questions associated with the relationship between organizational characteristics and clinician behavior; Whetten 1989) to better understand the relationship between organizational factors and outcomes of interest (Busse et al. 2016).

We explicitly selected variables for inclusion in this study that have shown both theoretical and empirical links with clinician practice use in mental health. Clinician variables of interest were attitudes toward and knowledge of EBPs, two key clinician-level constructs in implementation frameworks (Damschroder et al. 2009) that are considered proximal antecedents of EBP delivery (Brookman-Frazee and Stahmer 2018; Lyon et al. 2013). For organizational variables, a distinction has been made between general and implementation specific organizational factors (Durlak and DuPre 2008), both of which are linked to successful EBP implementation (Williams et al. 2017, 2018). Thus, we examined proficient organizational culture (norms and expectations that clinicians are competent in up-to-date practices and prioritize client well-being) and functional climate (perceptions that the work environment supports clinicians’ personal well-being) as general organizational factors associated with EBP use (Glisson 2002). We looked at implementation climate (perceptions that the use of EBP is expected, rewarded, and supported by the organization; innovation specific; Ehrhart et al. 2014) as an implementation-specific factor. These specific constructs were selected as prior empirical work has highlighted these constructs as particularly important for optimizing EBP delivery (Aarons et al. 2012; Beidas et al. 2015; Ehrhart et al. 2016; Williams and Glisson 2013, 2014a; Olin et al. 2014) and are consistent with identified possible mechanisms of change in organizational interventions (e.g., the Availability Responsiveness, and Continuity [ARC] intervention; Williams et al. 2017).

Based on work showing that organizational culture and climate are associated with therapists’ EBP attitudes, knowledge, and use (Glisson et al. 2012; Glisson et al. 2016; Powell et al. 2017; Williams et al. 2018), we anticipated that interactions between organizational culture and climate with clinician EBP attitudes and knowledge would explain practice use in a more nuanced way than direct associations. Specifically, we hypothesized that there would be boundary conditions to the effect of organizational culture and climate, with organizational factors predictive of EBP use only within the context of optimal levels of the examined clinician-variables (i.e., in the presence of positive attitudes, high knowledge) and that organizational variables would be less and/or not associated with clinician EBP use when clinicians had negative attitudes and/or low knowledge. Based on findings suggesting the importance of organizational factors relative to clinician factors as main effects of EBP use (Beidas et al. 2015; Durlak and DuPre 2008; Kam et al. 2003; Powell et al. 2017), we expected that in the absence of interactions, organizational characteristics would predict EBP use more strongly than clinician characteristics.

To evaluate these hypotheses, we were interested in two types of therapy approaches that vary in the extent to which they have been tested and studied in the literature: both EBP and other practices. Prior work has shown that when EBPs are delivered, they are often delivered alongside a variety of other treatment strategies that vary in the extent to which they have empirical support for their efficacy and effectiveness (Beidas et al. 2017; Garland et al. 2010). As a result, in addition to examining factors associated with EBP use to inform implementation strategy development, there is a need to examine factors associated with use of other, less evidence-based treatment strategies. Such work could both: (a) help inform an understanding of why clinicians continue to utilize treatment practices with less evidence within the context of EBP implementation efforts, and (b) potentially inform the design of strategies to de-implement the use of such other treatment strategies and facilitate the delivery of the EBP as intended (Niven et al. 2015; Prasad and Ioannidis 2014).

Our EBP of interest was cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which has the most empirical support for its efficacy across a range of youth mental health disorders (Dorsey et al. 2017; Higa-McMillan et al. 2016; Hofmann et al. 2012; McCart and Sheidow 2016; Weisz et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2015). CBT has been a target of implementation efforts across the country (Novins et al. 2013), including Philadelphia (Powell et al. 2016), where the current study was conducted. As a result, we would expect that community clinics high in organizational proficiency, functionality, and implementation climate would place an emphasis on the use of CBT techniques amongst their clinicians compared with other treatment practices with less evidence. Thus, CBT is an ideal EBP for advancing our understanding of implementation determinants and cross-level processes.

In terms of other treatment strategies, we were particularly interested in clinician use of psychodynamic therapy. While small studies of psychodynamic techniques show modest success (Abbass et al. 2013; Midgley et al. 2017), psychodynamic therapy is generally considered to not yet have sufficient empirical support for its use with youth (De Nadai and Storch 2013; Midgley et al. 2017) to be considered an EBP. Despite this, use of these techniques often persists in community practice (Beidas et al. 2017) and the organizational influences on use of these lesser supported techniques is poorly understood. Importantly, psychodynamic therapies are generally thought to be less cost-effective than CBT (Egger et al. 2016). Thus, low-resourced community settings may wish to prioritize use of CBT over psychodynamic strateiges, making it an important intervention for studying possible mechanisms of de-implementation.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

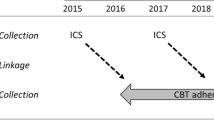

All procedures were approved by the City of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania institutional review boards. Cross-sectional surveys were collected from therapists as part of a larger longitudinal study examining the impact of a policy mandate on clinician use of EBPs for youth clients within the Philadelphia community mental health system (Beidas et al. 2013). The Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services (DBHIDS) in Philadelphia had supported four EBP implementation initiatives at the time of data collection (cognitive therapy, prolonged exposure, trauma-focused-CBT, and dialectical behavior therapy; see Powell et al. 2016 for an overview). Of note, all EBP initiatives placed emphasis on the use of CBT strategies, providing further support for studying CBT as the EBP of interest in this study. Clinicians attended a 2 h meeting during which research staff presented the study. Interested clinicians provided informed consent and completed questionnaires independently during this group meeting; they received $50 for participating. While clinicians completed measures, agency leadership was not present to facilitate clinician comfort in answering questions honestly.

Participants were 247 community mental health clinicians working in 28 youth-serving agencies in Philadelphia. Approximately 58% of clinicians employed by the 28 organizations participated in 2015. Participants averaged 38.7 years old (SD = 11.9), were largely female (n = 192, 77.7%), and of heterogeneous ethnic backgrounds (40.9% White, 16.2% Hispanic/Latino; 30.0% African American, 4.5% Asian, 4.0% Multiracial, 2% Other; 6 individuals did not report on their ethnicity). Average years of experience was 10.1 years (SD = 8.6). Just under half of clinicians (46.6%; n = 115) had participated in one of the EBP training initiatives sponsored by the Philadelphia DBHIDS (see Powell et al. 2016).

Measures

Clinician Practice Use

Clinicians’ use of CBT and psychodynamic therapy was measured using the Therapy Procedures Checklist—Family Revised (Weersing et al. 2002), a well-validated self-report measure (Kolko et al. 2009; Weersing et al. 2002). Consistent with the original developed measure (Weersing et al. 2002) and prior large-scale studies of clinician practice use in the public mental health system (e.g., Beidas et al. 2015, 2017), clinicians were asked to select a representative client on their caseload and indicate the extent to which they used 62 therapeutic techniques with that client over the course of that client’s treatment. All items are rated on a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (Rarely Use) to 5 (Use Most of the Time). To our knowledge, the TPC-FR is the only published self-report instrument of therapist practices that spans multiple treatment protocols and theoretical orientations; techniques measured are drawn from family, CBT, and psychodynamic therapy strategies. The TPC-FR yields subscales with total scores for each of these three treatment families. Prior work suggests that the TPC-FR demonstrates adequate psychometric properties, including test–retest reliability and sensitivity to within-therapist changes in technique use (Kolko et al. 2009; Weersing et al. 2002). Only the CBT and psychodynamic scales were used in this study, given our specific interest in clinician use of these therapeutic strategies. Example CBT items include “using time-out from reinforcement” and “training the child to recognize maladaptive thoughts.” Example psychodynamic items include “trying to understand the effects of early life experiences” and “analyzing the child’s dreams, fantasies, or other products (e.g., art).” Both subscales showed excellent internal consistency in this sample (CBT α = .92, Psychodynamic α = .87).

Clinician Characteristics

Clinicians’ attitudes towards EBP were assessed using the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS), which yields four subscales: appeal (EBP is intuitively appealing), requirements (would use EBP if required), openness (general openness to innovation), and divergence (perceived divergence between EBP and current practices; Aarons 2004). Higher scores indicate more favorable attitudes. The EBPAS has excellent psychometric properties (Aarons et al. 2010); in this sample, subscale alphas were > 0.70 (α range .72–.89), with the exception of the divergence subscale (α = .60), which showed internal consistency somewhat lower than those published in the national norms (Aarons et al. 2010). As such, we did not include the divergence subscale.

EBP knowledge was assessed with the Knowledge of Evidence-Based Services Questionnaire (KEBSQ; Stumpf et al. 2009), which is one of the only existing measures of youth mental health practice knowledge with psychometric support. The KEBSQ is a 40-item multiple true–false self-report measure that assesses knowledge of EBP techniques on a scale of 0–160; higher scores indicate more EBP knowledge. Prior analysis demonstrated that the KEBSQ demonstrates acceptable psychometric properties, including test–retest reliability, discriminative validity, and sensitivity to change over time (Stumpf et al. 2009).

Organizational Characteristics

Organizational proficiency culture and functional climate were assessed using the Organizational Social Context Measurement System (OSC), a well-validated measure developed specifically to assess organizational culture and climate in mental health and social service organizations (Glisson et al. 2008, 2012). These factors are theorized to be key organizational factors linked to EBP use (Williams and Glisson 2014b; Williams et al. 2017). The proficiency scale assesses an organization’s proficiency culture, or the norms and behavioral expectations for clinicians to place the well-being of clients first, be responsive to client needs, and be competent in up-to-date treatment practices. The functionality scale assesses an organization’s functional climate, or the extent to which clinicians perceive they can get their job done effectively and have a well-defined understanding of how they fit within the organization. Scoring yields a T-score with a μ = 50 and σ = 10 (Glisson et al. 2008). OSC profiles were calculated by the OSC development team. Of note, OSC profiles for each organization are usually created by creating an average score by agency composed of responses from front line service providers. However, two of our organizations did not have enough front line providers to create the OSC profile without including agency leaders. As aggregate statistics (i.e., awg) were acceptable and empirical work suggests that agreement in small organizations between leaders and followers is high (Beidas et al. 2018); we included agency leaders in the total profile score for those two organizations only. Higher scores on the OSC subscales indicate more proficient and functional organizational cultures.

Implementation climate was assessed via the 18-item Implementation Climate Scale (ICS) total score (Ehrhart et al. 2014). The ICS assesses multiple factors that contribute to successful implementation including: organizational focus on EBP, educational support for EBP, recognition for using EBP; rewards for using EBP; selection of staff for EBP; and selection of staff for openness. The ICS has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Ehrhart et al. 2014). Higher scores on the ICS indicate higher levels of implementation climate. Organization-level scores were calculated by aggregating (i.e., averaging) items across clinicians within each organization based on evidence of adequate within-organization agreement (average within group agreement values = .73–.99; LeBreton and Senter 2008).

Analysis Plan

Preliminary analyses confirmed the need for a multilevel approach, as there was significant inter-organizational variance in CBT (ICC = .15) and psychodynamic therapy (ICC = .06) use. Of note, while the ICC for psychodynamic therapy is considered relatively small, it is consistent with prior studies in community mental health (Beidas et al. 2015) and is thought to be a meaningful proportion of variance to proceed with examining predictors (Zyzanski et al. 2004). We first examined bivariate relationships between each predictor of interest and clinicians’ EBP use via two-level mixed effects models with random organization intercepts to account for clinicians nested within agencies. Next, we ran two-level mixed-effects regression models to test the cross-level interactions between organizational (level 2) and clinician (level 1) characteristics in predicting clinicians’ CBT and psychodynamic use. Each model contained all clinician predictors, a single organizational characteristic, and their interactions.Footnote 1 All variables were grand-mean centered prior to computing interaction terms. Significant interactions were probed via simple slopes and plotted at ± 1.5 SD of the mean of each independent variable. Main effects were interpreted for variables without significant interactions. All analyses were conducted using SAS PROC MIXED and controlled for whether clinicians had participated in a system-sponsored CBT training (Powell et al. 2016) and years of clinical experience. All presented coefficients are unstandardized to facilitate interpretation; coefficients reflect estimated changes in the dependent variable as a result of one point increases in the independent variable, controlling for the effects of other variables in the model.

Results

Bivariate Analyses

Table 1 shows clinician and organization means, standard deviations, and bivariate results illustrating the relationships between each variable and practice use. Greater CBT use was associated with higher EBPAS Openness scores, lower EBP knowledge, and more proficient organizational cultures. Higher psychodynamic therapy use was associated with higher EBPAS Openness scores and lower EBP knowledge.

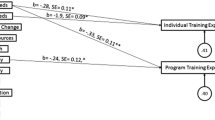

Interactions Predicting CBT

Table 2 shows results of the mixed effects models examining the cross-level interactions between clinician and organization characteristics in predicting CBT use; Fig. 1 illustrates the patterns of significant interactions. There was a significant interaction between the EBPAS Appeal subscale and both proficiency culture and functional climate (proficiency b = .02, p = .003; functionality b = .02, p = .004) scales, such that more proficient cultures and more functional climates predicted greater CBT use when clinicians viewed EBPs as intuitively appealing (proficiency b = .04, p < .001; functionality b =.02, p = .06), but was not associated with CBT use when clinicians viewed EBPs as unappealing (proficiency b = − .002, p = .82; functionality b = − .01, p = .51). There was also a significant interaction between EBP knowledge and proficiency culture (b = − .01, p = .03), such that higher proficiency culture was associated with higher CBT use when clinicians had low EBP knowledge (b = .03, p = .001) but was not related at high levels of EBP knowledge (b < − .001, p = .99; Fig. 2). Implementation climate did not interact with any clinician variables to predict CBT use.

Main Effects of CBT

As not all predictors showed interactions, a follow-up mixed-effects regression model containing only the predictors (i.e., no interaction terms) indicated that higher clinician openness to new practices was a main effect of more CBT use (EBPAS Openness b = .17), controlling for all other predictors (ps < .01). Implementation climate and the EBPAS Requirements subscale were not main effects of CBT use.

Interactions Predicting Psychodynamic Therapy

Table 2 shows the results for psychodynamic therapy; Fig. 2 illustrates the pattern for significant interactions. There was a significant interaction between EBP knowledge and implementation climate (b = − .02, p = .04), such that lower EBP knowledge was marginally associated with higher use of psychodynamic strategies at low levels of implementation climate (b = − .02, p = .05) but was more strongly associated with lower psychodynamic strategy use in the presence of high implementation climate (b = − .04, p < .001). Proficiency culture and functional climate did not interact with clinician variables to predict psychodynamic strategy use.

Main Effects of Psychodynamic Therapy

A mixed-effects model containing no interactions indicated that higher clinician openness to new practices was a main effect of more psychodynamic therapy use (EBPAS Openness b = .14), controlling for all other predictors in the model (p < .05). Proficiency culture, functional climate, and the EBPAS Appeal and Requirements subscales were not main effects of psychodynamic therapy use.

Discussion

Although conceptual models of implementation suggest that clinician and organization factors interact to influence practice use, few studies have explored this empirically. Empirical work in this vein is essential to furthering causal theory in implementation science. Overall, our findings suggested that the extent to which organizational factors influence a clinician’s practice may be dependent on clinician attitudes toward and knowledge of EBPs. This is consistent with conceptual theory suggesting the presence of cross-level interactions. Specifically, findings provide preliminary support for a “necessary but not sufficient” conceptualization of the role of organizational culture and climate. In other words, results supported the assertion that optimizing organizational culture and climate is important for successful EBP use, but also suggested that there may be boundaries to the effect of organizational context as a function of clinician characteristics.

Findings from this study suggest that optimal outcomes (highest CBT use, lowest psychodynamic technique use) may occur when there is synergy between organizational and clinician constructs. This is consistent with prior work that suggests the need for multi-level implementation and de-implementation strategies. However, our findings extend prior literature by highlighting that fostering an optimal organizational culture and climate to facilitate EBP use be an insufficient implementation strategy when clinicians in an organization hold negative attitudes and lower EBP knowledge. Thus, our data suggest that it is possible that organizational-level implementation strategies may be sufficient when clinicians are relatively positive to and generally knowledgeable about EBPs. However, a multi-level approach targeting both clinicians and organizations is likely to be particularly important when implementing EBPs for clinicians with lower knowledge and more negative toward EBPs.

Importantly, our results demonstrated that while multiple clinician and organization variables were predictive of clinician practices in this study, relying on main effects analyses alone (as is typical in the extant literature) was misleading. For example, while bivariate associations indicated that clinicians working within more proficient cultures (i.e., those that place emphasis on being up to date with the latest evidence and improving client well-being) reported higher CBT use on average, interactions indicated proficient culture was associated with higher CBT use primarily for those clinicians who viewed EBPs as appealing; there was no effect of proficient culture on CBT use for clinicians with more negative attitudes. Similarly, neither functional organizational climate nor implementation climate were associated with clinician practice use in the bivariate analyses but both variables showed conditional effects on outcomes. Specifically, higher functional climates predicted increased CBT use only for those clinicians who view EBPs as appealing and higher implementation climates predicted lower psychodynamic therapy use predominantly only when clinician knowledge of EBP was high. This highlights the importance for future empirical work to move beyond testing the main effects of predictors, as examining main effects alone obscures a more complex picture of interacting variables.

All significant interactions in this study provided support for a synergistic effect between therapist characteristics and organizational culture and climate. Hypothesizing specific explanations for these interaction results is critical to building casual theory and understanding potential causal pathways influencing clinician EBP use. Identifying these causal pathways will allow identification of possible mechanisms that can be targeted in future implementation studies. With respect to interactions predicting CBT use, examination of items on the EBPAS appeal subscale suggest that certain items assess how likely clinicians are to use EBP if it is used by colleagues who are happy with it (Aarons 2005). A respondent’s attitudes on the appeal subscale may therefore be more malleable to the organizational context as a function of the extent to which an individual looks to and connects with others in their organization to inform their practice. EBP knowledge also interacted with proficiency culture, suggesting that higher proficiency culture positively impacted CBT use primarily for clinicians with lower EBP knowledge, with less impact for those with high knowledge. One possible explanation for this is that organizational cultures in which clinicians are expected to be up to date on EBPs effectively pull clinicians with lower EBP knowledge toward the mean with respect to CBT use.

With respect to potential explanations for interactions predicting psychodynamic technique use, a combination of high EBP knowledge and high implementation climate led to the lowest levels of psychodynamic technique use. This suggests that fostering a strong implementation climate may have an impact on reducing use of, or de-implementing, psychodynamic interventions, but only when clinicians have a strong knowledge base of EBPs. It is also worth noting that there was relatively less variance in psychodynamic practice use attributable to the organization than for CBT (psychodynamic ICC = .06, CBT ICC = .15). Given that data were collected within a system actively training and supporting clinician use of CBT across organizations (and not psychodynamic techniques), it is possible that higher use of psychodynamic practices use may represent a more “independent” decision and thus primarily driven by clinician-level factors. This would also be consistent with prior work suggesting that organizational factors may function differently as a function of the extent to which an intervention requires more interdependence within an organization (Jacobs et al. 2014).

Contrary to our hypothesis that in the absence of interactions organizational factors would more strongly relate to clinician practice use, the only main effect was a clinician-level variable. Clinician openness to new practices related to higher CBT and psychodynamic technique use regardless of organizational context. The EBPAS openness items may tap into a more general openness to innovation, rather than EBP specifically (Aarons 2005), and clinician openness may be a primary driver of adopting a variety of innovations into practice (i.e., eclecticism). Given that openness can be construed as a personality construct (McCrae and Costa 1987), it may be less malleable to organizational influences. This further supports the importance of multilevel implementation and de-implementation strategies. Taken together, results point to several hypotheses that can be tested in future work to further understanding of the causal mechanisms at play within the context of implementation efforts.

Several limitations are worth noting. While we attempted to select variables consistent with prior theory and empirical work to enhance parsimony, it is possible other organizational factors interact with clinician variables to predict practice use or that there may be interactions within levels [e.g., organizational culture with climate; (Williams and Glisson 2014b)]. Additionally, data were cross-sectional, and we were unable to test mediation relationships, (e.g., whether organizational context influences EBP use through changes in therapists’ attitudes); the presence of interactions in this study highlights the importance of examining the mechanisms underlying these interactions in prospective work. We also looked at implementation climate for EBPs broadly, consistent with published psychometrics of the ICS (Ehrhart et al. 2014; Ehrhart et al. 2016); other work has found it to be beneficial to ask about innovations at a more specific level (e.g., CBT rather than EBP; Jacobs et al. 2014). Results may have differed had we asked about implementation climate for CBT specifically, rather than EBP broadly.

In addition, while a major strength of this paper is our ability to extend prior work examining relative contributions of clinician and organizational factors to clinician practice use that used similar, self-reported practice use to reach conclusions, self-reported use has limitations. Self-report does not always correlate with observational data (Hurlburt et al. 2010) and clinicians may over-report the amount of EBP in their practice (Creed et al. 2016). We also asked clinicians to report their use of therapy techniques with a representative client on their caseload, rather than a comprehensive examination of therapist practices. It is not known the extent to which reports about a representative client will generalize across a full clinician caseload.

Finally, some of our coefficients were relatively small; there is likely variation in clinician practices unexplained by our predictors and interactions. One important variable that likely contributes to variation is clinician practices is client characteristics (Benjamin Wolk et al. 2016) and we did not assess whether the specific CBT strategies clinicians endorsed were clinically appropriate for their client’s unique presentations. While the examination of three-way interactions (organization by therapist by client characteristics) would stretch the bounds of our sample beyond appropriate, future work with larger datasets should explore these complex interactive processes to more fully explain variation in clinician practice use. Furthermore, while self-report represents the most feasible method of assessing clinician practice (Schoenwald and Garland 2013), future work would benefit from replicating findings with observational data and with multiple identified clients on clinicians’ caseloads. In addition, it will be important for all interactions to be replicated in additional samples.

Conclusions

Findings support frameworks suggesting a complex interplay between organizational and individual implementation determinants as they relate to practice use and extends theory by empirically demonstrating there may be boundary conditions to the impact of organizational culture and climate for EBP implementation in mental health. Results underscore the importance of future empirical work studying interaction effects within the context of implementation efforts and suggest the potential value of attending to clinician characteristics in tandem with organizational culture and climate in implementation and de-implementation efforts.

Notes

As the high number of predictors and interactions may stretch the limits of the sample size and increases risk for multicollinearity, we also tested each interaction independently. Results were largely unchanged, suggesting we retain the overall models for parsimony. Inter-correlations between subscales of the EBPAS were small to moderate (all r < .33) further supporting the decision to retain the overall models. Inter-correlations between organizational proficiency and implementation climate were high (r = .50), suggesting each organizational variable be examined separately.

References

Aarons, G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65.

Aarons, G. A. (2005). Measuring provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice: Consideration of organizational context and individual differences. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14(2), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.008.

Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., Farahnak, L. R., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2015). Leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI): A randomized mixed method pilot study of a leadership and organization development intervention for evidence-based practice implementation. Implementation Science, 10(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0192-y.

Aarons, G. A., Glisson, C., Green, P. D., Hoagwood, K., Kelleher, K. J., & Landsverk, J. A. (2012). The organizational social context of mental health services and clinician attitudes toward evidence-based practice: A United States national study. Implementation Science, 7(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-56.

Aarons, G. A., Glisson, C., Hoagwood, K., Kelleher, K., Landsverk, J., & Cafri, G. (2010). Psychometric properties and US National norms of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 356. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019188.

Abbass, A. A., Rabung, S., Leichsenring, F., Refseth, J. S., & Midgley, N. (2013). Psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of short-term psychodynamic models. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(8), 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.014.

Becker, E. M., Smith, A. M., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2013). Who’s using treatment manuals? A national survey of practicing therapists. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(10), 706–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.008.

Beidas, R. S., Aarons, G., Barg, F., Evans, A., Hadley, T., Hoagwood, K., et al. (2013). Policy to implementation: Evidence-based practice in community mental health - study protocol. Implementation Science. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-38.

Beidas, R. S., Marcus, S., Aarons, G. A., Hoagwood, K. E., Schoenwald, S., Evans, A. C., … & Adams, D. R. (2015). Predictors of community therapists’ use of therapy techniques in a large public mental health system. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(4), 374-382. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3736

Beidas, R., Skriner, L., Adams, D., Wolk, C. B., Stewart, R. E., Becker-Haimes, E., et al. (2017). The relationship between consumer, clinician, and organizational characteristics and use of evidence-based and non-evidence-based therapy strategies in a public mental health system. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 99, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.08.011.

Beidas, R. S., Williams, N. J., Green, P. D., Aarons, G. A., Becker-Haimes, E. M., Evans, A. C., … & Marcus, S. C. (2018). Concordance between administrator and clinician ratings of organizational culture and climate. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(1), 142-151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0776-8

Benjamin Wolk, C., Marcus, S. C., Weersing, V. R., Hawley, K. M., Evans, A. C., Hurford, M. O., et al. (2016). Therapist-and client-level predictors of use of therapy techniques during implementation in a large public mental health system. Psychiatric Services, 67(5), 551–557.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Haine, R. A., Baker-Ericzén, M., Zoffness, R., & Garland, A. F. (2010). Factors associated with use of evidence-based practice strategies in usual care youth psychotherapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0244-9.

Brookman-Frazee, L., & Stahmer, A. C. (2018). Effectiveness of a multi-level implementation strategy for ASD interventions: Study protocol for two linked cluster randomized trials. Implementation Science, 13(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0757-2.

Busse, C., Kach, A. P., & Wagner, S. M. (2016). Boundary conditions: What they are, how to explore them, why we need them, and when to consider them. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 574–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116641191.

Creed, T. A., Wolk, C. B., Feinberg, B., Evans, A. C., & Beck, A. T. (2016). Beyond the label: Relationship between community therapists’ self-report of a cognitive behavioral therapy orientation and observed skills. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0618-5.

Czincz, J., & Romano, E. (2013). Childhood sexual abuse: Community-based treatment practices and predictors of use of evidence-based practices. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 18(4), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12011.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

De Nadai, A. S., & Storch, E. A. (2013). Design considerations related to short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(11), 1213–1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.08.012.

Dorsey, S., McLaughlin, K. A., Kerns, S. E., Harrison, J. P., Lambert, H. K., Briggs, E. C., et al. (2017). Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1220309.

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0.

Egger, N., Konnopka, A., Beutel, M. E., Herpertz, S., Hiller, W., Hoyer, J., … & Wiltink, J. (2016). Long‐term cost‐effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy versus psychodynamic therapy in social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 33(12), 1114-1122. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22540

Ehrhart, M. G., Aarons, G. A., & Farahnak, L. R. (2014). Assessing the organizational context for EBP implementation: The development and validity testing of the Implementation Climate Scale (ICS). Implementation Science, 9(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0157-1.

Ehrhart, M. G., Torres, E. M., Wright, L. A., Martinez, S. Y., & Aarons, G. A. (2016). Validating the implementation climate scale (ICS) in child welfare organizations. Child Abuse and Neglect, 53, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.017.

Garland, A. F., Brookman-Frazee, L., Hurlburt, M. S., Accurso, E. C., Zoffness, R. J., Haine-Schlagel, R., et al. (2010). Mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems: A view inside therapists’ offices. Psychiatric Services, 61(8), 788–795. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2010.61.8.788.

Glisson, C. (2002). The organizational context of children’s mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(4), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1020972906177.

Glisson, C., Green, P., & Williams, N. J. (2012). Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of child welfare systems: Implications for research and practice. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36(9), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.002.

Glisson, C., Landsverk, J., Schoenwald, S., Kelleher, K., Hoagwood, K. E., Mayberg, S., et al. (2008). Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1–2), 98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5.

Glisson, C., & Williams, N. J. (2015). Assessing and changing organizational social contexts for effective mental health services. Annual Review of Public Health, 36(1), 507–523. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122435.

Glisson, C., Williams, N. J., Hemmelgarn, A., Proctor, E., & Green, P. (2016). Increasing clinicians’ EBT exploration and preparation behavior in youth mental health services by changing organizational culture with ARC. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 76, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.11.008.

Henggeler, S. W., Chapman, J. E., Rowland, M. D., Halliday-Boykins, C. A., Randall, J., Shackelford, J., et al. (2008). Statewide adoption and initial implementation of contingency management for substance-abusing adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 556. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.76.4.556.

Higa-McMillan, C. K., Francis, S. E., Rith-Najarian, L., & Chorpita, B. F. (2016). Evidence base update: 50 years of research on treatment for child and adolescent anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(2), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1046177.

Higa-McMillan, C. K., Nakamura, B. J., Morris, A., Jackson, D. S., & Slavin, L. (2015). Predictors of use of evidence-based practices for children and adolescents in usual care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(4), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0578-9.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1.

Hurlburt, M. S., Garland, A. F., Nguyen, K., & Brookman-Frazee, L. (2010). Child and family therapy process: Concordance of therapist and observational perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(3), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0251-x.

Jacobs, S. R., Weiner, B. J., & Bunger, A. C. (2014). Context matters: Measuring implementation climate among individuals and groups. Implementation Science, 9(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-46.

Jensen-Doss, A., Hawley, K. M., Lopez, M., & Osterberg, L. D. (2009). Using evidence-based treatments: The experiences of youth providers working under a mandate. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 417. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014690.

Kam, C.-M., Greenberg, M. T., & Walls, C. T. (2003). Examining the role of implementation quality in school-based prevention using the PATHS curriculum. Prevention Science, 4(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021786811186.

Kolko, D. J., Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Baumann, B. L., & Knudsen, K. (2009). Community treatment of child sexual abuse: A survey of practitioners in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 36(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0180-0.

LeBreton, J. M., & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106296642.

Lewis, C. C., Klasnja, P., Powell, B., Tuzzio, L., Jones, S., Walsh-Bailey, C., et al. (2018). From classification to causality: Advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 136. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00136.

Lim, A., Nakamura, B. J., Higa-McMillan, C. K., Shimabukuro, S., & Slavin, L. (2012). Effects of workshop trainings on evidence-based practice knowledge and attitudes among youth community mental health providers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(6), 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.03.008.

Lyon, A. R., Ludwig, K., Romano, E., Leonard, S., Vander Stoep, A., & McCauley, E. (2013). “If it’s worth my time, I will make the time”: School-based providers’ decision-making about participating in an evidence-based psychotherapy consultation program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(6), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0494-4.

McCart, M. R., & Sheidow, A. J. (2016). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(5), 529–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1146990.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81.

Midgley, N., O’Keeffe, S., French, L., & Kennedy, E. (2017). Psychodynamic psychotherapy for children and adolescents: an updated narrative review of the evidence base. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 43(3), 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/0075417x.2017.1323945.

Nelson, T. D., & Steele, R. G. (2007). Predictors of practitioner self-reported use of evidence-based practices: Practitioner training, clinical setting, and attitudes toward research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 34(4), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0111-x.

Niven, D. J., Mrklas, K. J., Holodinsky, J. K., Straus, S. E., Hemmelgarn, B. R., Jeffs, L. P., et al. (2015). Towards understanding the de-adoption of low-value clinical practices: A scoping review. BMC Medicine, 13(1), 255. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0488-z.

Novins, D. K., Green, A. E., Legha, R. K., & Aarons, G. A. (2013). Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practices for child and adolescent mental health: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(10), 1009–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.07.012.

Olin, S. S., Williams, N., Pollock, M., Armusewicz, K., Kutash, K., Glisson, C., et al. (2014). Quality indicators for family support services and their relationship to organizational social context. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0499-z.

Powell, B. J., Beidas, R. S., Rubin, R. M., Stewart, R. E., Wolk, C. B., Matlin, S. L., et al. (2016). Applying the policy ecology framework to Philadelphia’s behavioral health transformation efforts. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 43(6), 909–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0733-6.

Powell, B. J., Mandell, D. S., Hadley, T. R., Rubin, R. M., Evans, A. C., Hurford, M. O., et al. (2017). Are general and strategic measures of organizational context and leadership associated with knowledge and attitudes toward evidence-based practices in public behavioral health settings? A cross-sectional observational study. Implementation Science, 12(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0593-9.

Prasad, V., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2014). Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implementation Science, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-1.

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., et al. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Schoenwald, S. K., & Garland, A. F. (2013). A review of treatment adherence measurement methods. Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029715.

Stumpf, R. E., Higa-McMillan, C. K., & Chorpita, B. F. (2009). Implementation of evidence-based services for youth: Assessing provider knowledge. Behavior Modification, 33(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445508322625.

Tabak, R. G., Khoong, E. C., Chambers, D. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2012). Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(3), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.024.

Wandersman, A., Duffy, J., Flaspohler, P., Noonan, R., Lubell, K., Stillman, L., … Saul, J. (2008). Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3-4), 171-181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9174-z

Weersing, V. R., Weisz, J. R., & Donenberg, G. R. (2002). Development of the therapy procedures checklist: A therapist-report measure of technique use in child and adolescent treatment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(2), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1207/153744202753604458.

Weisz, J. R., Kuppens, S., Ng, M. Y., Eckshtain, D., Ugueto, A. M., Vaughn-Coaxum, R., … & Weersing, V. R. (2017). What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: A multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. American Psychologist, 72(2), 79. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040360

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495.

Williams, N. J., Ehrhart, M. G., Aarons, G. A., Marcus, S. C., & Beidas, R. S. (2018). Linking molar organizational climate and strategic implementation climate to clinicians’ use of evidence-based psychotherapy techniques: Cross-sectional and lagged analyses from a 2-year observational study. Implementation Science, 13(1), 85.

Williams, N. J., & Glisson, C. (2013). Reducing turnover is not enough: The need for proficient organizational cultures to support positive youth outcomes in child welfare. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(11), 1871–1877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.09.002.

Williams, N. J., & Glisson, C. (2014a). The role of organizational culture and climate in the dissemination and implementation of empirically supported treatments for youth. In R. Beidas & P. Kendall (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation of evidence based practices in child and adolescent mental health (pp. 61–81). New York: Oxford University Press.

Williams, N. J., & Glisson, C. (2014b). Testing a theory of organizational culture, climate and youth outcomes in child welfare systems: A United States national study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38(4), 757–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.003.

Williams, N. J., Glisson, C., Hemmelgarn, A., & Green, P. (2017). Mechanisms of change in the ARC organizational strategy: Increasing mental health clinicians’ EBP adoption through improved organizational culture and capacity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0742-5.

Zhou, X., Hetrick, S. E., Cuijpers, P., Qin, B., Barth, J., Whittington, C. J., et al. (2015). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of psychotherapies for depression in children and adolescents: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.202.

Zyzanski, S. J., Flocke, S. A., & Dickinson, L. M. (2004). On the nature and analysis of clustered data. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2(3), 199–200.

Funding

Funding for this research project was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant K23MH099179 to Dr. Beidas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Beidas receives royalties from Oxford University Press and has served as a consultant for Merck, Dohme, & Sharp. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Becker-Haimes, E.M., Williams, N.J., Okamura, K.H. et al. Interactions Between Clinician and Organizational Characteristics to Predict Cognitive-Behavioral and Psychodynamic Therapy Use. Adm Policy Ment Health 46, 701–712 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00959-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-019-00959-6