Abstract

This study explored the association between coaching and the implementation of the Good Behavior Game (GBG) by 129 urban elementary school teachers. Analyses involving longitudinal data on coaching and teacher implementation quality indicated that coaches strategically varied their use of coaching strategies (e.g., modeling, delivery) based on teacher implementation quality and provided additional support to teachers with low implementation quality. Findings suggest that coaching was associated with improved implementation quality of the GBG. This work lays the foundation for future research examining ways to enhance coach decision-making about teacher implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Classroom-based universal preventive interventions have been shown to reduce problems and strengthen resilience among children in both the short- and long-term (Hahn et al. 2007; Kellam et al. 2008; Petras et al. 2008; Wilson and Lipsey 2007). Research linking the quality of program fidelity and dosage with student outcomes highlights the significance of implementation quality for the effectiveness of preventive interventions (Derzon et al. 2005; Ialongo et al. 1999). Given the growing concern about the quality with which research-based programs are implemented in schools, there is increased interest in different types of implementation support to optimize the quality of program delivery, and in turn translate into improved outcomes for students (Domitrovich et al. 2008; Fixsen et al. 2005).

One type of implementation support that is gaining attention is coaching, yet, there has been relatively limited research documenting characteristics of this professional development approach (Stormont et al. 2013). Moreover, there have been mixed findings regarding the extent to which coaching is associated with improved outcomes for students (Pas et al. in press). The current paper presents data from a randomized trial testing the impact of a set of classroom management and social-emotional learning prevention programs, in which a coaching model was employed to support the teachers’ implementation of the programs. Several aspects of the coaching process were examined, including specific coaching behaviors (e.g., modeling, feedback), the amount of time teachers received coaching, and the number of coaching contacts, which were hypothesized to be associated with improved implementation of classroom-based prevention programs. This year-long coaching process provided the opportunity to examine the association between coaching activities and improved implementation as reflected in measures of program fidelity and dosage.

Coaching as an Implementation Support

Results of multiple meta-analyses suggest that implementation supports such as training and ongoing coaching are integral to program implementation (Fixsen et al. 2005; Greenhalgh et al. 2005). A growing body of research indicates that traditional “workshop” trainings alone are not sufficient to enhance program implementation in the natural setting, like schools (Fixsen et al. 2005). Much of the interest in coaching within educational settings was motivated by the meta-analysis by Joyce and Showers (2002), in which they reported that training comprised of didactics, demonstrations, practice, and feedback does little to impact teacher practice unless it is coupled with classroom-based support. As summarized below, there is also more recent empirical research exploring the impacts of this form of professional development on both implementation and student outcomes (e.g., Cappella et al. 2012).

There are many different definitions of the term “coaching”, which often appear along with related concepts such as “consultation” and “mentoring”. There is no consensus regarding the distinction among these terms, nor is there agreement about the exact nature and intensity of the activities involved in coaching, although some progress has been made toward developing conceptual models of coaching (American Institutes for Research 2004). Accumulating research across different fields suggests that opportunities for observation, practice, performance feedback, and reflection are critical components that may be critical to skill development by program deliverers (e.g., Fixsen et al. 2005; Herschell et al. 2010; van Driel et al. 2001).

Coaching can occur in multiple settings but is likely to have the greatest impact when it is embedded in the context in which an intervention is implemented, which in the current study was the classroom (Garret et al. 2001). The goal of coaching teachers is to improve their use of a specific practice, such as the implementation of a program or general teaching skills. To meet this goal, coaches often use a variety of strategies, such as conducting needs assessments through observations of the teachers’ implementation of the program and review of program dosage documentation. The data collected through needs assessments guide the coaching process and help the coach monitor progress. Another commonly used coaching technique is modeling the implementation by demonstrating core program activities. Similarly, coaches my provide instruction to teachers on the components of an intervention, general technical assistance that is informational in nature, and constructive feedback. Coaches may also assist in problem solving around a particular student challenge or implementation barrier (e.g., finding time in the day to implement). Conducting periodic, brief check-ins to prompt and encourage the teacher to implement the program is another helpful coaching technique (for reviews, see American Institutes for Research 2004; Denton and Hasbrouck 2009; Domitrovich et al. 2008). Research has linked these and other practices with better student outcomes (Curby et al. 2009; Pianta et al. 2008a).

Research on the Effectiveness of Coaching

Despite the growing interest in coaching as a practice for supporting implementation, there has been relatively limited systematic investigation of coaching linking it explicitly with implementation or student outcomes. A recent randomized trial (i.e., Cappella et al. 2012) documented positive effects of the Bridging Mental Health and Education in Urban Schools (BRIDGE; Cappella et al. 2011) model, which aimed to increase classroom interactions and address the needs of children with behavioral challenges. Relative to a condition of teacher training alone, those in the combined coaching and training condition experienced significant improvements in the closeness of teacher–student relationships, students’ academic self-concept, and students’ experience of victimization by peers (Cappella et al. 2012).

Similarly, the MyTeachingPartner Program (Pianta et al. 2008c) is a video-based coaching model designed to improve the quality of teacher–student interactions in classrooms. The coaching process in this model utilizes the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta et al. 2008b), which is an observational measure of teaching quality, to score videotapes of teachers’ practice. The scores are used as a benchmark by the coach to identify teacher behaviors to target with feedback and to set as goals through collaborative discussion. A randomized trial of MyTeachingPartner at the pre-kindergarten level demonstrated impacts on CLASS ratings (Pianta et al. 2008a) and children’s receptive language skills (Mashburn et al. 2010). A second trial produced similar effects on teacher–student interactions and student achievement in secondary schools (Allen et al. 2011). While the findings from BRIDGE and MyTeachingPartner are favorable, some studies of classroom coaching and consultations models have produced mixed effects (see American Institutes for Research 2004; Pas et al. in press). This suggests a need for more research on coaching to identify which types of supports are most promising for optimizing implementation of prevention approaches, which may in turn translate to improved student outcomes.

Overview of the Current Study

Although randomized trials of some coaching models suggest that coaching is more effective than the absence of this form of support (e.g., Cappella et al. 2012), well-articulated guides of the coaching practices that support teacher implementation of prevention programs are lacking in the literature (Stormont et al. 2013). It is also unclear whether all teachers benefit equally from coaching or if coaching needs to be tailored in terms of types of supports, amount of time, or number of contacts.

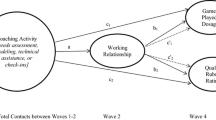

Within the current paper, coaching was defined as the provision of guidance to teachers to promote understanding and support skill development as well as their adequate use of preventive interventions in their classrooms (Denton and Hasbrouck 2009). This paper describes the coaching practices employed by a team of coaches aiming to optimize the implementation of the Good Behavior Game (GBG; Barrish et al. 1969; Embry et al. 2003), a widely used universal prevention program. Teachers received training and on-site support for the intervention from expert and highly-supervised coaches who worked for the project and were familiar with the interventions (see Becker et al. 2013a for more about the coaching model). The two main goals of the paper were to examine how coaches tailored their coaching practices according to the quality of teacher implementation of the GBG and whether coaching was associated with improved implementation quality and dosage.

It was hypothesized that coaches would tailor their coaching practices to meet the needs of each teacher. Specifically, it was expected that teachers with lower skills would receive more coaching as well as more intensive coaching activities (e.g., modeling, feedback, delivery). Additionally, it was hypothesized that coaching would be associated with improved implementation of the GBG. Together, these findings are intended to inform the implementation of coaching models, and the potential for tailoring coaching efforts to optimize impact.

Method

Design Overview

The context of the study was a randomized trial in which teachers delivered the GBG along with a social emotional learning curriculum (i.e., Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies; PATHS). The teachers of 140 classrooms in grades K-5 across 12 schools were recruited to participate in this study as program implementers. These schools were located in a large urban, east coast public school district (see participating school demographics in Table 1). Recruitment occurred at the school level such that all principals agreed to participate in the year-long project and allow their teachers to receive training and coaching in the interventions; however, teacher participation in the training and data collection activities was voluntary.

Participants

Teachers

Of the 140 eligible classroom teachers, 11 provided insufficient data for the current analysis. Specifically, 6 left the school prior to January and were excluded from the analyses due to the absence of implementation data. Other reasons for exclusion from the present analyses include a lack of complete data included refusal to deliver the intervention (n = 2), midyear maternity leave that interrupted data collection (n = 2), and death due to circumstances unrelated to the program (n = 1). Thus, 129 teachers were included in the current analyses.

The proportions of teachers who taught kindergarten (15.5 %), 1st grade (20.2 %), 2nd (18.6 %), 3rd (15.5 %), 4th (16.3 %), and 5th grades (14.0 %) were approximately equal due to the intentional enrollment of entire elementary schools. Teachers reported their educational attainment as bachelors (40.3 %), master’s (45.7 %), post-master’s (5.4 %), and doctoral degrees (0.8 %). Teachers were overwhelmingly female (90.7 %). With regard to age, 41.1 % self-reported their age to be 20–30 years old, 24.0 % were 31–40, 8.5 % were 41–50, 14 % were 51–60, and 4.7 % were older than 60 years. Teacher ethnicity was not assessed in this study.

Coaches

Three former school teachers employed by the research team served as coaches. All were Caucasian and two were female. Two of the coaches were former implementers of the GBG in a previous pilot study, and thus had implemented the program in their classroom for at least a year prior to joining the team as a coach. All coaches received intensive training over several months in the theory of the intervention, common challenges encountered by teachers, and the process of coaching the interventions from the intervention developers. They also co-conducted the teacher trainings with the intervention developers. A coaching manual (Becker et al. 2013b) was developed to guide the coaching process and to ensure consistency over time and across coaches.

PAX Good Behavior Game (GBG; Barrish et al. 1969; Embry et al. 2003)

Originally developed by Barrish et al. (1969), the GBG encourages teachers to utilize social learning principles within a team-based, game like context to reduce aggressive/disruptive and off-task behavior and, consequently, facilitate academic instruction. The PAX GBG represents Embry et al. (2003) efforts to improve the effectiveness of the original GBG (Embry et al. 2003). Like the original GBG, the PAX GBG is a group-based token economy, where the groups or “teams” are reinforced for their collective success in inhibiting inappropriate behavior. The team based nature of the “game” also allows teachers to take advantage of peer pressure in managing student behavior at the individual as well as the classroom level. The additional “PAX” elements introduced by Embry et al. (2003) primarily consist of verbal and visual cues that teachers and classmates use to promote attentive and prosocial student behaviors and a positive classroom environment. The GBG has a long history of successful implementation and positive academic, behavioral, and substance use outcomes in urban public schools (e.g., Bradshaw et al. 2009; Ialongo et al. 1999, 2001; Kellam et al. 2008; Petras et al. 2008).

Coaching Procedures

Teachers attended a one-day training workshop for the PAX GBG consisting of didactics, discussion, demonstration, and video review led by Dr. Embry, the program developer, with support from the coaches. Coaches were assigned individually to schools and each coach worked with the teachers across 1–3 schools per year. Schools and their respective teachers received coaching for one school year each. The present analyses include data from teachers who participated in one of two year-long cohorts. Data were collected during an intervention period of 31 weeks.

Coaches were expected to meet with each teacher approximately once a week. Coaches followed a two-phased coaching model that was developed in collaboration with teachers over the course of seven years (for additional details, see Becker et al. 2013a). Briefly, the coaching model involved a universal coaching phase lasting approximately 4–6 weeks after the workshop trainings in the interventions, during which coaches used the same coaching strategies with all teachers. As shown in Table 2, these activities include check-ins, modeling, needs assessments (e.g., observations), and technical assistance/performance feedback. Coaches followed consistent timelines and manualized guidelines regarding modeling, observations, and feedback (Becker et al. 2013b).

At the end of this 6-week period, coaches accompanied members of the research team who conducted the first of four independent observations of teachers’ program delivery and completed an implementation rubric rating (see description in measure section). Following the first observation, coaches provided written and verbal feedback to each teacher based on the rubric ratings.

The tailored coaching phase followed the initial rubric rating, during which coaches developed individualized plans regarding the type and intensity of coaching support each teacher needed. Coaches continued to collect data on a weekly basis about the number and duration of games played (i.e., dosage). Based on these data, together with the formal quarterly implementation rubrics and less formal structured observations, coaches varied the form and intensity of coaching supports provided to the teachers. Coaches were expected to have some contact with all teachers on a weekly basis but the frequency, intensity, and nature of the activities differed based on teachers’ level of skill and use of the GBG. Coaches continued to use a variety of strategies (i.e., modeling, observation and feedback) with all teachers but provided more intensive support to those teachers whose data reflected low implementation. The coaching process reflected an adaptive approach in which the coaching was tailored to fit the needs of the teacher. This tailoring could include any combination of longer (e.g., 60-min vs. 15-min) or more frequent (e.g., daily rather than weekly) coaching visits, or more intensive coaching activities to scaffold skill development (e.g., in vivo prompting while teacher plays the game). It might also involve other coaching targets (e.g., classroom organizational skills, general behavior management skills) in addition to the interventions. Coaching activities for the universal and tailored coaching phases were manualized (Becker et al. 2013b) and coaches used a program calendar that ensured consistency in the significant benchmarking activities of the coaching model.

Coach Supervision

Coaches attended weekly supervision meetings, conducted by three doctoral-level psychologists with expertise in behavioral interventions, during which coaching activities and teacher implementation were reviewed. The coaches discussed individual teachers and plans to help teachers maintain implementation or to reduce barriers to implementation were developed and monitored during each supervision session. The coaches and their supervisors also reviewed teacher implementation rubric data and the number of times the GBG was played each week by each teacher to ensure that the coaching process was data-driven. Additionally, the supervisors occasionally accompanied coaches into the field to observe classroom and coaching activities to ensure high quality and consistent implementation of the coaching model. The program developers were also available to the coaches through email and phone calls, and annual on-site visits to provide consultation and technical assistance to the coaches regarding challenges cases and problem-solving barriers to implementation.

Measures

Coaching Activities

Coaches completed the Coach Visit Log (Bradshaw and Domitrovich 2008) for each coaching contact that lasted five minutes or longer. The coach log reflects one-on-one coaching activities; therefore, attendance at team meetings and meetings with administrators were not recorded in these logs. The total number of coaching contacts was calculated by summing each contact. Coaches indicated the type of coaching activity performed by endorsing any of 16 coaching activities (e.g., check-in, modeling, technical assistance, needs assessment) listed on the form or by filling in additional activities in an “other” category. The percentage of effort (0–100 %) was tracked for each activity type, which was subsequently converted by the research staff to minutes. For ease of interpretation, certain coaching categories were combined for the present analyses (e.g., separate categories for “modeling PAX cues” and “modeling GBG” were combined into “modeling PAX Cues/GBG”), yielding 9 categories of coaching activities. The time coaches spent delivering each type of coaching activity was calculated by summing the number of minutes in that category. The total time coaching was the total number of minutes spent coaching across all 16 categories.

GBG Dosage

Teachers completed a weekly log of the number of GBG games played and the duration of each game using a “scoreboard” designed for this purpose. The coaches collected the teacher logs on a weekly basis. These data were summed across the 31-week implementation period and yielded two variables: total number of games implemented and total number of minutes implementing the GBG.

GBG Quality

Independent observers completed the PAX Good Behavior Game Implementation Rubric (Schaffer et al. 2006) at four time points throughout the academic year to assess each teacher’s implementation quality. Due to scheduling issues, coaches, rather than independent observers, completed 8.5 % of the implementation rubrics in the present study. During the implementation quality assessment, teachers were asked to “play” a 5–10-min GBG game. The implementation rubric included 29 items that mapped onto the following 7 dimensions reflecting core components of the game: (a) preparing students for the game (5 items), (b) choice of activity (3 items), (c) use of timer (3 items), (d) teams (4 items), (e) response to inappropriate behavior (4 items), (f) prizes (6 items), and (g) after the game (4 items). Independent observers rated teachers on each dimension using a 5-point scale. The seven ratings were then averaged to provide a mean implementation rating for each teacher. Higher scores reflect better quality implementation. Interrater reliability for the implementation rubrics was high (ICC = .93). For the purpose of the present study, implementation rubric observations that occurred during the fall (hereafter referred to as “round 1”) served as an initial measure of teacher implementation quality with the GBG. Final implementation rubrics that occurred in May of the same school year (“round 4”) were used as an outcome variable, thereby reflecting teacher proficiency following coaching.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We explored the extent to which teacher age and grade level were associated with the outcome variables of interest (i.e., round 4 implementation quality, time spent playing the GBG, number of games played) in order to determine which variables should be included in the primary models as covariates. Neither teacher age nor grade level was significantly related to any of the outcomes of interest. Round 1 implementation quality (i.e., implementation rubric score) was significantly correlated with round 4 implementation quality (r = .40, p < .05) and time spent playing the GBG (r = .21, p < .05).

Initial Implementation Quality

The 129 teachers were categorized into two groups based on their round 1 implementation rubric scores for the GBG. High quality implementing teachers (n = 71; 55.0 %) were those whose round 1 rubric scores were at least 3.43 on a scale from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating greater proficiency. Low quality implementing teachers (n = 58; 45.0 %) were those whose round 1 rubric scores were less than 3.43. This classification was based on a median split in the rubric frequency data and an a priori expectation that rubric scores of approximately 3.5 indicated high proficiency. The mean round 1 rubric scores for the low quality implementing group was 2.74 (SD = .48) and for the high quality implementing group was 3.65 (SD = .16).

Coaching Activities

Using the universal and tailored coaching phase data, a series of analyses were conducted to examine the frequency of coaching activities and the effects of teacher implementation quality on coaching activities.

Universal Coaching Phase

During the universal phase of coaching, the number of coaching contacts with teachers ranged from 2 to 14 (M = 5.48, SD = 2.07). The total time coaches spent with the teachers before the round 1 implementation rubrics ranged from .58 to 4.92 h (M = 1.99 h, SD = .75 h). Table 3 presents the time spent and number of contacts for each different coaching activity. Of all the coaching activities, coaches spent the most total time (35.6 % of the total time) conducting needs assessments, followed closely by modeling (24.9 %). When engaging in this activity, coaches spent the bulk of their time modeling specific components of the PAX GBG program (94.6 %) as opposed to general teaching or behavior management practices (5.4 %). Coaches also spent time engaged in check-ins (15.8 %), technical assistance/feedback regarding the GBG (14.5 %), and other coaching activities (7.0 %). Coaches rarely engaged in implementation tracking support (1.4 %) and program delivery (0.8 %).

A multivariate analysis explored for differences in the total time spent coaching and the number of coaching sessions based on teachers’ implementation quality at the end of the universal coaching phase. This analysis confirmed that the total time spent coaching and the number of coaching sessions did not differ based teacher implementation quality, F (2, 125) = 0.64, p = .53 (see Table 2).

Tailored Coaching Phase

During the tailored coaching phase, the number of coaching sessions conducted ranged from 8 to 60 (M = 33.19, SD = 11.50; see Table 3). The total amount of time coaches spent with teachers ranged from 1.33 to 27.5 h (M = 7.81, SD = 3.55). The relative frequencies of coaching activities also changed between the universal phase to the tailored phase. During the tailored coaching phase, coaches spent the most time conducting check-ins (42.0 % of the total time), followed by needs assessments (24.2 %). Technical assistance/feedback (10.1 %), other coaching activities (9.1 %), and implementation tracking support (8.2 %), all occurred with similar frequency and were more frequent than modeling (3.5 %) and coach delivery of program components (2.9 %).

Analyses explored for potential differences in the total time spent coaching and the number of coaching sessions, contrasting teachers considered high versus low implementing. The overall multivariate analysis was significant, F (2, 125) = 3.65, p = .03. Follow-up univariate analyses indicated that the mean frequency of coaching sessions was approximately once a week for high and low quality implementing teachers (see Table 3). However, coaches spent significantly more total time with low than with high quality implementing teachers, F (1, 127) = 4.63, p = .03 (Table 3).

Multivariate analyses also indicated that the time spent in each coaching activity also varied by implementation quality grouping, F (9, 118) = 2.01, p = .04. Coaches spent more time with low quality implementing teachers than with high quality implementing teachers in all coaching activities except for check-ins, and a few of these differences in time reached significance in univariate analyses. Specifically, coaches spent more time modeling the GBG, modeling general teaching skills, and delivering the GBG when working with teachers in the low versus high implementation group (Table 3).

Teacher Implementation of the PAX GBG

Dosage

During the 31-week intervention phase, teachers spent 30.25 h (SD = 27.90) playing an average of 180.06 (SD = 110.95) games. There was no difference in GBG dosage based on high versus low round 1 implementation quality grouping, F (2, 122) = 1.10, p = .34. Specifically, the number of hours spent playing the GBG did not differ between teachers with low (M = 26.42, SD = 30.14) versus high (M = 33.37, SD = 25.73) round 1 implementation quality groupings. Furthermore, there was no difference in the number of games played by teachers classified as low (M = 171.40, SD = 122.73) versus high (M = 187.24, SD = 100.49) quality implementing teachers.

Quality Improvement

As expected, round 4 implementation rubric scores (M = 3.40, SD = 0.50) for the entire sample were significantly higher than round 1 implementation rubric scores (M = 3.25, SD = 0.57), t (128) = 2.93, p = .004, suggesting significant improvement in implementation quality over the course of the year. On average, implementation scores increased by 0.15 U (SD = 0.59). Teachers classified as low quality implementers at round 1 demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in their round 4 rubric scores (M = 0.45, SD = 0.61) than the teachers who were classified as high quality implementers at round 1 (M = −0.09, SD = 0.44), F (1, 125) = 34.19, p < .001. For teachers who started out as high quality implementers, the round 4 rubric scores (M = 3.65, SD = 0.16) were not significantly different than their round 1 rubric scores (M = 3.56, SD = 0.43), t (70) = 1.78, p = .80. In contrast, the round 4 rubric scores of teachers who started out as low implementing teachers (M = 3.20, SD = 0.51) were significantly higher than their round 1 rubric scores (M = 2.75, SD = 0.48), t (57) = 5.61, p < .001. Overall, the round 4 rubric scores of teachers who started out rated as high quality were significantly higher than those who started out classified as low implementing teachers, F (1, 127) = 19.21, p < .001.

Discussion

The current paper used data from a randomized controlled trial involving two classroom-based intervention programs (i.e., PAX GBG and PATHS) to explore the association between coaching and quality of implementation of the PAX GBG. One goal of this study was to describe the nature, dosage, and sequencing of coaching activities that, to date, have rarely been presented in the literature (Stormont et al. 2013). Coaches spent their time engaged in a variety of tasks, some of which shifted over the course of the year. For example, during the initial 4–6 weeks of coaching following the training (i.e., universal coaching phase), coaches primarily focused on conducting observations to assess teachers’ implementation needs, followed by modeling various strategies and program components, conducting check-ins, and providing technical assistance and feedback. These coaching activities delivered at the beginning of the intervention period was consistent with the intended universal model in which coaches relied on a high degree of regular contact with teachers in order to encourage buy-in and to establish the GBG as part of the teachers’ routine as soon as possible. Based on the literature, modeling and technical assistance with feedback was expected to result in high quality implementation of the GBG. By the round 1 rubric observation, 55 % of teachers exhibited high levels of implementation (rubric ratings >3.43).

Following the round 1 rubric observations (i.e., tailored coaching phase), coaches spent the most time conducting check-ins, followed by needs assessments and technical assistance and feedback. There were noticeable shifts in the proportion of time spent in the various coaching activities. For example, modeling accounted for 24.9 % of coaching time during the universal coaching phase, but dropped to 3.5 % of coaching time during the tailored phase. This shift in the overall frequency of modeling is not surprising given this was a standard coaching strategy delivered to all teachers at the beginning of the intervention. As the school year progressed and more teachers mastered the game, the need for modeling decreased.

In contrast, check-ins accounted for 15.8 % of coaching time during the universal phase, this coaching activity increased as the year progressed and accounted for 42.0 % of coaching time during the tailored phase. As the year progressed, brief contacts were sufficient to maintain the skills and implementation dosage for many teachers. Needs assessments and concomitant technical assistance/feedback also decreased slightly from the universal phase to the tailored coaching phase when teachers demonstrated their implementation skills.

Coaches broadened the scope of their coaching activities during the tailored coaching phase. When modeling and providing technical assistance/feedback during the universal phase, coaches focused primarily on PAX GBG. During the tailored phase, coaches increased the proportion of time they spent modeling and providing technical assistance/feedback regarding general teaching and behavior management practices. Taken together, the results related to the frequency of coaching activities are novel in that they highlight specific patterns of coaching practices over time, such as how specific coaching activities (e.g., modeling) were utilized as an early coaching support and phased out over time. Moreover, they suggest that coaches used certain coaching strategies to enhance teacher skills outside of the GBG, the primary focus of coaching.

Consistent with an adaptive model of coaching, the findings from the current study confirmed that coaches strategically varied their coaching efforts based on teacher implementation quality. During the universal phase, teachers received coaching at the same frequency and duration regardless of their implementation quality, a finding that confirms that coaches followed a standardized coaching model. As hypothesized, during the tailored coaching phase that followed the round 1 implementation rubric, coaches spent more time with teachers who demonstrated low implementation quality. Additionally, coaches used more modeling of the PAX GBG with low implementing teachers. Repeated modeling was often an effective way for coaches to show teachers the success of the GBG on increasing on-task behavior and reducing classroom disruptions for their own students, thereby engaging teachers to implement the GBG.

Related, coaches also modeled general teaching strategies more frequently for low implementing teachers, suggesting that coaches perceived that these teachers could benefit from demonstration of skills that extended beyond the GBG, including effective academic instruction, classroom organization, or classroom management. Addressing these needs was important because teachers who struggled with general teaching were generally more likely to experience difficulty implementing the GBG, which is a relatively simple intervention to deliver. It is important to recognize that low implementation quality can also be a function of classroom composition. There may be a certain threshold of behavior problems in a classroom that is too high to respond effectively to a universal intervention such as the GBG and may require more tailored interventions for those students who are most disruptive. The GBG relies on the social reinforcement of positive peers but if the levels of negative peer contagion are too high this process might not be possible.

Coaches also spent more time in direct delivery of the intervention with teachers in the low implementation quality group than those in the high implementation quality group. This is likely due to the primary goal of the larger randomized controlled trial within which this study was set of testing the GBG intervention, thereby requiring adequate intervention dosage. Coaching data did not show more frequent coaching visits for low implementing teachers. This is likely due to the fact that the low implementing group included teachers who had more frequent coaching visits (usually for a week or two), teachers who continued to have weekly coaching visits, and teachers who frequently canceled their coaching sessions and so brought down the mean frequency for the low quality implementing group.

Another finding was that teacher implementation quality improved over time. Teachers who started off with high implementation quality continued to maintain that level. Low implementing teachers tended to improve the most over the course of the project, perhaps because they had more room for improvement than high implementing teachers, yet as a group they did not achieve an implementation level comparable to that of teachers who implemented at a high level early on. In the future, it will be important to validate the implementation rubric to determine the magnitude of improvement required to make a meaningful impact on student outcomes.

Limitations and Areas for Future Research

It is important to consider some limitations of this research when interpreting these findings. Consistent with the group randomized controlled trial design (Murray 1998), the random assignment to condition occurred at the school level, rather than the teacher level. The level of coaching was not random, as it was intended to be phased, whereby all teachers received the universal coaching model, and others with greater needs received enhanced support during the tailored phase. There may also be some school-level factors unmeasured in the current study (e.g., principal leadership; Kam et al. 2004) which affect all the teachers within a school. A related consideration is that we did not adjust for the clustering of teachers within schools, as teachers within schools may be more similar to each other, and thus non-independent (Murray 1998). Future studies will apply a multilevel approach, in which we both adjust for the clustering of teachers and include potential school-level factors, such as principal leadership or organizational context, which are hypothesized to influence implementation (Domitrovich et al. 2008).

The sample size was also relatively small, which may have limited our power to detect some significant effects; the relatively small sample also limited our ability to conduct some more advanced analyses of the overall pattern of coaching supports or trajectories of coaching and/or implementation over time. Although we did not have detailed data on the fidelity of the quality of the interactions between the coaches and teachers, the coaches were supervised weekly. During these sessions, the coach logs were reviewed to ensure that the coaches were following the activities of the coaching model and to develop action plans for teachers needing additional supports. In the future it would be helpful to record the coaching sessions to provide a stronger indicator of fidelity and because coaching requires a great deal of interpersonal skill to influence behavior change with an individual while also maintaining a working relationship. The coach log also could be improved to further elucidate the “other” coaching activities category to better understand the additional strategies (e.g., reinforcement, goal setting) coaches use.

This study was exploratory, in that it focused on the coaching practices of just 3 coaches who worked with 129 teachers. Although an extensive amount of practice-based testing and expert consultation informed the development of coaching practices over time, it is possible that the coaching repertoires of the coaches were not varied enough to meet each teacher’s needs. This may be particularly true for those low implementing teachers whose implementation quality did not improve over time. However, it is clear that for the majority of teachers, coaching was sufficient to support at least adequate, if not high implementation quality. Additionally, due to the small number of coaches, it is possible that there were coach effects that influenced the results. An examination of our data explored this possibility and found that there were school-level differences in implementation quality and dosage. Moreover, coaching data examined within coach but across schools showed variation, suggesting that it is a plausible conclusion that coaching varied based on some of the factors explored in this study (e.g., implementation quality, intervention condition), rather than simply as a function of the coach.

The implementation rubric may not have been sensitive enough to detect some of the variation in implementation quality, and changes in quality over time. We also used a cut-point of 3.43 for categorizing high versus low quality implementation; this number was based on the distribution of the data in the current sample, with consideration of the range of possible scores on the implementation rubric scale. However, additional examination of the rubric data is needed to determine which rubric dimensions distinguish high- from low-quality implementers. Additionally, rather than relying solely on a quality indicator to categorize teachers as was done in this study, a multifaceted construct that takes into account quality and delivery dosage might further distinguish high- from low-implementing teachers and yield even more distinctions in coaching practices. This is important because the association between GBG quality and dosage was not high. Further exploring this line of research could elucidate the level of implementation quality and dosage necessary for impacting student outcomes. Future approaches for addressing this issue could include sensitivity and specificity analyses, thereby linking different levels of quality, as well as dosage, with improvements in behavioral and academic outcomes for students.

Also critical to the coaching process is the formation of an alliance or close collaboration between the coach and the teacher (Wehby et al. 2012), as this relationship likely creates as safe context for self-disclosure, honest discussion, and a joint commitment to the goals of the program and the collaborative work (Reinke et al. 2011). Exploration of data on the coach/teacher alliance will permit examination of the extent to which the relationship between the coaches and teachers is associated with various aspects of the coaching process, including the amount of time spent together, the number of coaching visits, and the types of support provided. Alliance may also influence the impact of the coaching on implementation and student outcomes. Another area to explore in future studies is the role of incentives, as the coaches in this project occasionally provided modest incentives (e.g., $10 gift cards, T-shirts) to teachers with high implementation or those progressing toward their implementation goals. Incentives are often utilized in studies, but are rarely examined systematically. This study was also conducted in an urban, inner-city community; therefore, additional research is needed to determine the extent to which these findings generalize to other school settings.

Conclusions and Implications

The findings of this study highlight the importance of coaching as a support system for optimizing implementation quality of classroom-based preventive interventions. These results also illustrate some of the complexity associated with coaching, and the dynamic process that unfolds over time. Coaches use different types of information in order to develop a plan for supporting teachers, which appear to be tailored to meet the teachers’ needs. What is also promising to see is that over half of the teachers met the high implementation quality ratings after a relatively modest level of training (i.e., one to two days) and coaching (i.e., one month). This suggests that the models can be implemented with high quality by most teachers, and that phased coaching models may be useful in tailoring the needs of teachers requiring additional supports. The analyses also suggested that assessments of skill early in the implementation process (i.e., one month post-training) are moderately predictive of subsequent implementation, and can also be useful in determining which teachers require additional coaching supports to be successful. We found that coaching, regardless of the specific form, is helpful for optimizing implementation, as it was associated with improvements in implementation quality over the course of the year. Taken together, these findings emphasize the importance of developing a data-informed coaching process to ensure high quality implementation of classroom-based preventive interventions. Science, and ultimately the benefits to students, can be advanced by promoting wider scale dissemination and testing of coaching models.

References

Allen, J., Pianta, R., Gregory, A., Mikami, A., & Lun, J. (2011). An interaction-based approach to enhancing secondary school instruction and student achievement. Science, 333, 1034–1037.

American Institutes for Research. (2004). Conceptual overview: Coaching in the professional development impact study. Unpublished manuscript.

Barrish, H., Saunders, M., & Wolf, M. (1969). Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 2, 119–124.

Becker, K., Darney, D., Domitrovich, C., Keperling, J., & Ialongo, N. (2013a). Supporting universal prevention programs: A two-phased coaching model. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Becker, K., Domitrovich, C., Darney, D., Keperling, J., & Ialongo, N. (2013b). Coaching classroom-based interventions: A step-by-step guide. Unpublished manuscript.

Bradshaw, C. P., & Domitrovich, C. E. (2008). Coach Visit Log. Unpublished instrument. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Center for Prevention and Early Intervention.

Bradshaw, C., Zmuda, J., Kellam, S., & Ialongo, N. (2009). Longitudinal impact of two universal preventive interventions in first grade and educational outcomes in high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 926–937.

Cappella, E., Jackson, D. R., Bilal, C., Hamre, B. K., & Soule’, C. (2011). Bridging mental health and education in urban elementary schools: Participatory research to inform intervention development and implementation. School Psychology Review, 40, 486–508.

Cappella, E., Hamre, B. K., Kim, H. Y., Henry, D. B., Frazier, S. L., Atkins, M. S., et al. (2012). Teacher consultation and coaching within mental health practice: Classroom and child effects in urban elementary schools. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 597–610.

Curby, T. W., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Ponitz, C. C. (2009). Teacher–child interactions and children’s achievement trajectories across kindergarten and first grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 912–925.

Denton, C. A., & Hasbrouck, J. (2009). A description of instructional coaching and its relationship to consultation. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 19, 150–175.

Derzon, J. H., Sale, E., Springer, J. F., & Brounstein, P. (2005). Estimating intervention effectiveness: Synthetic projection of field evaluation results. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26, 321–343.

Domitrovich, C., Bradshaw, C., Poduska, J., Hoagwood, K., Buckley, J., Olin, S., et al. (2008). Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: A conceptual framework. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 1, 6–28.

Embry, D., Staatemeier, G., Richardson, C., Lauger, K., & Mitich, J. (2003). The PAX good behavior game (1st ed.). Center City, MN: Hazelden.

Fixsen, D., Naoom, S., Blase, K., Friendman, R., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: The National Implementation Research Network, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida.

Garret, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915–945.

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., Kyriakidou, O., & Peacock, R. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 61, 417–430.

Hahn, R., Fuqua-Whitley, D., Wethington, H., Lowy, J., Crosby, A., Fullilove, M., et al. (2007). Effectiveness of universal school-based programs to prevent violent and aggressive behavior: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33, s114–s129.

Herschell, A., Kolko, D., Baumann, B., & Davis, A. (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 448–466.

Ialongo, N., Poduska, J., Werthamer, L., & Kellam, S. (2001). The distal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on conduct problems and disorder in early adolescence. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9, 146–160.

Ialongo, N., Werthamer, L., Kellam, S., Brown, C., Wang, S., & Lin, Y. (1999). Proximal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on the early risk behaviors for later substance abuse, depression, and anti-social behavior. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 599–641.

Joyce, B., & Showers, B. (2002). Student achievement through staff development (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kam, C., Greenberg, M., & Kusche, C. (2004). Sustained effects of the PATHS curriculum on the social and psychological adjustment of children in special education. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 12, 66–78.

Kellam, S., Brown, C. H., Poduska, J., Ialongo, N., Wang, W., Toyinbo, P., et al. (2008). Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95S, S5–S28.

Mashburn, A., Downer, J., Hamre, B., Justice, L., & Pianta, R. (2010). Consultation for teachers and children’s language and literacy development during pre-kindergarten. Applied Developmental Science, 14, 179–196.

Murray, D. (1998). Design and analysis of group-randomized trials. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pas, E., Bradshaw, C. P., & Cash, A. (in press). Coaching classroom-based preventive interventions. In M. D. Weist, N. A. Lever, C. P. Bradshaw, & J. Owens (Eds.), Handbook of school mental health: Advancing practice and research (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Petras, H., Kellam, S., Brown, C., Muthén, B., Ialongo, N., & Poduska, J. (2008). Developmental epidemiological courses leading to antisocial personality disorder and violent and criminal behavior: Effects by young adulthood of a universal preventive intervention in first- and second-grade classrooms. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95(Suppl. 1), 45–59.

Pianta, R., Belsky, J., Vandergrift, N., Houts, R., & Morrison, F. (2008a). Classroom effects on children’s achievement trajectories in elementary school. American Educational Research Journal, 45, 365–397.

Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K., & Hamre, B. K. (2008b). Classroom assessment scoring system. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Pianta, R., Mashburn, A., Downer, J., Hamre, B., & Justice, L. (2008c). Effects of web-mediated professional development resources on teacher–child interactions in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 431–451.

Reinke, W., Herman, K., & Sprick, R. (2011). Motivational interviewing for effective classroom management: The classroom check-up. New York: Guilford Press.

Schaffer, K., Rouiller, S., Embry, D., & Lalongo, N. (2006). The PAX good behavior game implementation rubric. Unpublished technical report, Johns Hopkins University.

Stormont, M., Reinke, W. M., Newcomer, L., Darney, D. & Lewis, C. (2013). Coaching teachers’ use of social behavior interventions to improve children’s outcomes: A review of the literature. Manuscript submitted for publication.

van Driel, J., Beijaard, D., & Verloop, N. (2001). Professional development and reform in science education: The role of teachers’ practical knowledge. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38, 137–158.

Wehby, J., Maggin, D., Partin, T., & Robertson, R. (2012). The impact of working alliance, social validity, and teacher burnout on implementation fidelity of the good behavior game. School Mental Health, 4, 22–33.

Wilson, S. J., & Lipsey, M. W. (2007). School-based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behavior: Update of a meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33, S130–S143.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Grants from the Institute of Education Sciences [R305A080326] and the National Institute of Mental Health [P30 MH08643, T32 MH18834]. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the coaches who participated in this project: Sandra Hardee, Jennifer Keperling, Michael Muempfer, and Kelly Schaffer. The authors also appreciate the invaluable expertise of Drs. Mark Greenberg and Dennis Embry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Becker, K.D., Bradshaw, C.P., Domitrovich, C. et al. Coaching Teachers to Improve Implementation of the Good Behavior Game. Adm Policy Ment Health 40, 482–493 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0482-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0482-8