Abstract

Programs to improve police interactions with persons with mental illness are being initiated across the country. In order to assess the impact of such interventions with this population, we must first understand the dimensions of how police encounters are experienced by consumers themselves. Using procedural justice theory as a sensitizing framework, we used in-depth semi-structured interviews to explore the experiences of twenty persons with mental illness in 67 encounters with police. While participants came into contact with police in a variety of ways, two main themes emerged. First, they feel vulnerable and fearful of police, and second, the way police treated them mattered. Findings elaborate on dimensions of procedural justice theory and are informative for police practice and mental health services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Programs to improve police interactions with persons with mental illness are being initiated in jurisdictions across the country. These efforts include Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) and educational programs presented during academy and inservice trainings (National Council of State Governments 2002). There is a growing body of research on factors that influence police response to persons with mental illness and the effectiveness of interventions such as CIT. However, in order to assess the impact of such interventions on the successFootnote 1 of police encounters with this population, we must first understand the relevant dimensions of how police encounters are experienced by consumers themselves.

Procedural justice theory has proven useful for examining the experiences of persons with mental illness in other parts of the justice system, for example, mental health courts and civil commitment proceedings (Cascardi et al. 2000; Lidz et al. 1995; Poythress et al. 2002). Studies have found that when individuals with mental illness evaluate a legal interaction as being high in procedural justice they report feeling less coerced and are more likely to cooperate with authorities (Poythress et al. 2002). Here, we use procedural justice theory as a sensitizing framework to consider the experiences of persons with mental illness in encounters with police.

The study described in this article explores police encounters from the perspective of persons with mental illness. First, we explore the nature of police encounters and general expectations/perceptions of police among a sample of persons receiving community mental health services. We then explore their experiences in these encounters and conditions associated with both positive and negative evaluations, and in a few instances, violent struggles. In doing so, we identify themes consistent the procedural justice framework as well as emergent themes that are extremely informative to our understanding of how police interactions are experienced by persons with mental illness. Finally, we present advice and implications for police from the participants of the study and based on our analysis of their encounters.

Theoretical Framework

Police work involves a great deal of discretion, differing from other criminal justice activities in the range of incidents, formal and informal responses available and the low levels of supervision of officers. Unlike other criminal justice agents, police officers spend the majority of their time on order maintenance activities rather than responding to offenders or addressing the effects of violent crime (Walker and Katz 2005). While police officers have limited discretion when responding to violent crime, they have a range of formal and informal options available to respond to less serious crime (Terrill and Paoline 2007). In these incidents, officers have subjective authority; meaning that they do not make arrests for every illegal activity. Rather, the police must decide for which offenses they will take formal action and which they will address informally. There is little transparency in police encounters, particularly when officers employ informal responses. There are no written transcripts and citizens and police are often the only witnesses to these encounters. Individual officers receive little supervision or oversight in the course of their daily work activities. Thus, as discretionary agents, police officers possess a variety of options when encountering people with mental illness in the course of their everyday work and their decisions are likely shaped by an array of contextual considerations (Morabito 2007).

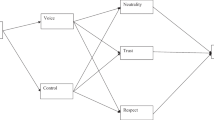

In considering how people with mental illness may respond to the discretionary actions of police, the social psychological concept of procedural justice provides a framework for considering subjective experiences of process that may be as or even more important than the actual outcome of an interaction (see Watson and Angell 2007). For example, an individual who feels unhappy about being arrested or involuntarily committed may evaluate the precipitating incident positively if he or she perceives that the outcome was determined through a fair process. The literature on procedural justice identifies key components or antecedents of procedural justice judgments (Lind and Tyler 1992): (1) voice-the opportunity to tell one’s side of the story and be heard by the authority; (2) dignity-being treated with respect by the authority; (3) trust-perceiving that the authority is genuinely concerned about one’s welfare.

Tyler and colleagues (1992, 2003) propose that people want to be treated fairly by authorities, independent of the outcome of the interaction. Fair treatment by an authority, operationalized in terms of voice, dignity and trust, shapes procedural justice judgments by signifying that the individual is a valued member of the group. This in turn facilitates cooperation by strengthening a person’s ties to the social order (Lind and Tyler 1992; Tyler and Blader 2003).

In a series of studies, Tyler and colleagues have found that when individuals feel that they have been treated with sufficient procedural justice, they are more likely to cooperate with police (Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler and Blader 2000). Evidence suggests that the reverse is also true. Individuals who feel that they are treated with procedural injustice may be less likely to cooperate with the police and more likely to rely on informal means of social control to address their own problems (Kane 2005; Carr et al. 2007). Perceived fairness is particularly pertinent in disadvantaged neighborhoods where the people may already have difficult relationships with the police (Kane 2005)—and these are the same communities where people with mental illness tend to reside (Draine et al. 2002). Thus, procedural justice is of great concern for people with mental illness in part by nature of the neighborhoods where they live.

Past research specific to persons with mental illness interacting with other parts of the justice system supports the procedural justice model. For example, studies have established that persons civilly committed for involuntary treatment are sensitive to procedural aspects of the hearing process (Greer et al. 1996), and hearing features consistent with procedural justice are related to more positive attitudes about participation in treatment (Cascardi et al. 2000). Findings from the Broward County (Florida) Mental Health Court evaluation suggest procedural justice is important to persons with mental illness in criminal proceedings as well. Participants in the court that perceived higher levels of procedural justice reported a more positive emotional experience, greater satisfaction with hearing outcomes, and feeling less coerced (Poythress et al. 2002). In sum, these findings suggest that procedural justice is crucial for cooperation and successful outcomes for persons with mental illness in encounters with the police.

Method

Study Interviews

Since little is known about consumers’ subjective perceptions of police encounters, this study employed qualitative methods suitable for exploratory concept development. Procedural justice theory was used as a sensitizing concept, however, because of its clear relevance to the phenomenon. In-depth semi-structured interviews were used to explore the experiences of persons with mental illness in encounters with police officers. Using a funneling approach, we began the interviews with broad open-ended inquiries in which participants were asked to describe their most recent encounters with the police. Subsequently, we used probes derived from the procedural justice literature to elicit specific information related to context, the participant’s behavior, the officer’s behavior, and the participant’s objective and subjective experience of the interaction. This series of questions was repeated for up to five police contacts. Participants were also asked about their general perceptions of police officers and whether they would offer any advice for them about responding to persons with mental illness. Interviews, which were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim, were conducted by the first author and a research assistant. All procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Participants were recruited from two psychosocial rehabilitation programs operated by Thresholds, Inc., a community mental health center serving multiple neighborhoods in Chicago. Thresholds is Illinois’ largest psychiatric rehabilitation center, serving over 4,000 people with mental illness annually at its 22 service locations and more than 40 housing developments in the Chicago area. We intentionally selected two program sites that differ in terms the demographics of the clientele and the communities they are located in. The Dincin Center is located on the near north side of the city very close to a neighborhood densely populated with nursing homes, group homes and mental health programs. It is rapidly gentrifying and becoming a predominantly white, higher income area, putting many of Thresholds members in conflict with new residents of the community and the police who experience community pressure to move them along and reduce their visibility. Thresholds South is located on the South side of the city and serves a predominantly African American population. The surrounding neighborhood is far less affluent, but more demographically stable. According to US Census Database (2000), over 55–69% of residents have lived in the same house for 5 years or longer compared to 32.4% for the neighborhood where the Dincin Center is located (www.Chicagotribune.com).

Eligibility criteria included having had an encounter (any type) with the police within the past 12 months, receiving services at Thresholds South or the Dincin Center, having a non-substance use Axis I diagnosis and being over 18 year old. Participants’ most recent contact had to have been within 12 months, however, we also asked them about up to four additional contacts that may have occurred more than 12 months prior to the interview.

In total, 26 individuals were recruited and completed study interviews. Due to recording equipment problems, however, six interviews were not useable. Sample characteristics described are for the 20 participants whose interviews were used in the analysis. Sixteen (80%) of the sample were male. Ages ranged from 29 to 63 years old, with a mean of 45.1 (SD 9.6) years. Ten (50%) participants identified as African American, six (30%) as White, two (10%) as multiracial, and two (10%) as other. Only one (5%) participant indicated Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. Eighteen (90%) participants were single/never married and one each (5%) indicated they were separated and divorced. Six (30%) participants indicated less than a high school education, 10 (50%) had graduated from high school, and four (20%) reported some college or vocational school. Annual household incomes reported ranged from 0 to $20,000, with a mean of $8,097 (SD $5,738).

Data Handling and Analysis

We used the dimensional analysis approach for analyzing data from grounded theory studies (Schatzman 1991; Caron and Bowers 2000). Conducting dimensional analysis involves a close scrutinization of the data to explain the phenomenon of interest (in this case, interactions between persons with mental illness and police officers) by rigorously examining the perspective from which the phenomenon is presented by the subjects, the context in which it is described, the dimensions of the phenomenon, the conditions under which it varies (for example, by type of contact, setting, outcome) and the consequences of the phenomenon.

The computer package Nvivo (QSR 7.0) was used to manage the transcript data. Based on the literature and an initial screen of 20% of the interviews by the primary and secondary authors, an initial categorical coding template was developed to code individual police contacts based on the type of contact and characteristics of the interaction as well as more general thoughts and feelings about the police. Coding was conducted by the first author and two research assistants. Disagreements during this process were discussed and resolved by consensus. Once initial coding was completed, comparisons and connections were made between categories to generate and assess rival hypotheses and to allow higher order themes to be identified.

Findings

Police encounters were used as the primary unit of analysis (as opposed to individual participants, since participants were permitted to discuss multiple contacts). Participants described one to five encounters each (mean 3.35, SD 1.04, mode 3.0) in varying levels of detail for a total of 67 separate encounters. The initial organization into categorical codes allowed us to characterize the nature of encounters between police and persons with mental illness and for subsequent comparison of cases and identification of higher-level themes and relationships. Given that encounters were the primary unit of analysis, participants reporting a greater number of incidents may be more heavily represented in the findings. However, we make every effort to present examples and quotes from all participants to illustrate the themes that emerged.

The Nature of Police Encounters

Individual encounters were coded in terms of where they occurred, how the participant came to the attention of police, and the behavior that brought them to police attention or reason for the contact. The majority of the encounters (49, 73.13%) occurred in public, while 11 (16.42%) occurred in the participants’ homes and 7 (10.45%) occurred in service agency or shelter settings. Police officers initiated 36 (53.73%) of the encounters and participants initiated 9 (13.43%). Twenty-two (32.85%) encounters were initiated by someone other than the participant calling the police, only two of those were calls made by family members.

Stated reasons for the contacts varied, but most often consisted of “street stops” for nuisance activity, minor criminal behavior, or in some cases, no apparent reason. Participants indicated they were regularly stopped and asked for identification or told they “resembled a suspect.” These types of stops combined with nuisance related stops (e.g. drinking in public) accounted for 24 (35.82%) of the encounters described. Twelve (17.91%) encounters were related to minor criminal behavior such as misdemeanor shoplifting, while only six (8.99%) encounters involved more serious criminal behavior such as felony drug possession or theft. Mental health crisis calls accounted for 12 (17.91%) of the encounters, and participants’ requests for police assistance accounted for seven (10.45%) encounters. The remaining six contacts described involved the participant being served a warrant or as a witness of a crime or accident.

Vulnerability and Negative Expectations of Police

In describing their experiences in contacts with police, many participants shared generally negative perceptions and expectations of police officers. Based on personal or second hand experience and general distrust of police, they expected to be treated badly and felt that many officers are corrupt and use authority illegitimately. This, along with their tenuous status in the community, made participants feel very vulnerable. Six participants specifically mentioned that the officers could have killed them right on the scene. One man, who reported being falsely accused of “pulling on a woman’s shirt” expressed relief at having come out of the encounter unharmed, stating:

……..because they could’ve took me to jail and killed me, you know. … I was scared enough to think that. I heard about police brutality when they attack you or something. They try to beat you into a confession or something, so I was kind of nervous like, you know, what’s going to happen to me now …..

Several participants commented more generally on feeling vulnerable to police brutality. One woman stated:

You just have to speak to them the best way you can and hope that you aren’t going to say something wrong. I know some police, they got that attitude that they would rather kill you…..And it’s been done around here.

Participants also felt vulnerable to being falsely arrested. One man, who felt targeted because he looked homeless, was stopped in a grocery store.

Well, I was shocked when they said you fit the description of someone robbing stores and I actually thought they were joking ….. knowing that I didn’t have an ID on me and technically could be arrested for vagrancy ……I was afraid that I was going to be wrongfully arrested.

Given their negative expectations and feelings of vulnerability, for many participants not being treated abusively was in itself a good outcome for which they felt relieved and satisfied. One participant stated, “I felt relieved that I survived the incident.” Another indicated, “Yeah, I was satisfied. They didn’t hit me or knock me around. They were just cool man.”

Evaluations of Police Encounters

Since the primary goal of the study was to better understand the experiential dimensions of encounters with police, we identified and categorized positive and negative aspects of these evaluations.

Conditions Associated with Positive Evaluations

As indicated above, for many participants, not being roughed up or abused was evaluated as a positive encounter, as it defied their expectations. Several additional themes emerged from narratives of encounters that were experienced positively. These themes pertained kindness and personal interaction, voice and fairness, and legitimacy.

A number of participants described encounters in which police officers went out of their way to show kindness or take a moment to put them at ease, for example, chatting with them or sharing a cigarette. Such characterizations were viewed as unusual and were often verbalized in contradistinction to other experiences individuals may have had in which officers behaved disrespectfully or abusively. One woman, who was caught shoplifting and arrested, provided a typical example.

The officer that arrested me, he was actually very kind. He treated me like a human. He offered me a cigarette, did I want a smoke, you know, and I’m like – that’s not normal. Normally they rough me up, you know, they have the cuffs on too tight. They talk to me like very degrading, but this officer was very kind….Like I said, he treated me with respect, not a thief.

In another encounter, police were called to a board and care home to transport a participant to the hospital after he had allegedly pulled a fire alarm under false pretenses. This particular individual felt wrongly accused of the offense by the home staff, but in contrast felt mollified by the police handling of the situation. Here again, the important feature of the encounter is the extra time the officer took to forge a personal connection and express concern for the participant rather than accuse him of wrongdoing:

Yeah, I was having a cigarette with one of the officers. Well he had an Italian last name but he said he wasn’t Italian. Talking about just stuff like that… whatever and I think I expressed that I didn’t want to be in hospital… They were concerned that I might hurt myself.

This theme evokes the procedural justice component of being treated with respect and dignity, but adds a texture of genuine human to human interaction in which the status distance between the participant and authority figure is experienced as leveled to some degree. The strategies officers used to narrow the perceived difference in power were basic displays of kindness and concern, and in some cases, delimited personal disclosure.

Consistent with the procedural justice framework, participants linked having the opportunity to tell their side of the story, or voice, to positive evaluations of encounters. Having voice was closely tied with perceptions of fairness. Police were called about one participant after he had an altercation with a staff person at his building. He felt the officers handled the situation fairly, as they listened to both parties involved, not just the staff person.

I explained to them what was going on and we had a talk about, you know, how I should, act, you know, and stuff like that, …calling the police was enough for me, because, I mean it’s not like they came to be on her side. They came to keep the peace, so, you know, that made me feel better. The police got there. They listened to the director. They listened to me.

Even when police did not behave kindly or give participants an opportunity to tell their side of the story, some participants’ encounters were evaluated positively because the participants perceived officers as acting legitimately within their role. For example, the phrase “they were just doing their job” came up repeatedly in participant narratives. One participant, who encountered police after he had created a disturbance at a social service agency, appreciated how the police responded even though he felt they did not go out of their way to be kind to him:

They were not necessarily nice about the way they talked to me but they gave me the exact information that I needed. I was uncomfortable with the way they spoke to me, but like I say, the point is they did their job, what was required of them and I really appreciate that.

Conditions Associated with Negative Evaluations of Police Encounters

Participants also described features of encounters that they experienced very negatively. Themes emerging from these narratives pertained to being “jumped” or “rushed” by police, unnecessary use of force and physical abuse, verbal abuse and disrespect and the absence of voice.

Rapid and forceful tactics have historically been used by the police to respond to uncertainty and suspicious activity (Skolnick and Fyfe 1993; Walker and Katz 2005). However, such swift and forceful handling can be confusing and jarring to the situational actors, who may respond erratically. Two participants that had interactions with police officers during mental health crises described feeling that officers rushed at them forcefully before they had the opportunity to comply with their directions. Both of these situations escalated to violent struggles. One man indicated he had been feeling suicidal and that upon realizing this, his building manager contacted police. When the police arrived, the participant was sitting on his couch in his underwear, unarmed. As he describes, the situation escalated very quickly:

Yes, when they came to my apartment, they had their guns drawn. They told me to lay down, lay down. I mean real coarse, “Get down, get down.” And then as I decided to go down because I didn’t want the police to get hurt, I was calming down and then they rushed me, threw me down on the ground, and kind of like grabbed me out of my apartment….It was scary.

Another man related a situation in which his mother had called the police to take him to the hospital after he broke some furniture. When the police arrived he was in his room with the door locked. The officers instructed him to open his bedroom door. Before he could comply, the police proceeded to pry the door open with a crowbar.

Then I got up and started putting on my clothes and they knocked on the door because I had it locked and before I could open it they pried it open with a crowbar and tore it off the hinge…..I said “Let me put some clothes on before you take me out of here.”….before I can grab the latch, here come the door busting open with a crowbar. …They didn’t really say nothing because I tried…While he was trying to handcuff me I was trying to keep him from handcuffing me and they both started pulling on me and wrestling me, trying to get me down on the floor. It was just a big fight

Some participants described encounters that featured more straightforward instances of harsh or callous treatment, in which the officers were physically abusive and used unnecessary force. One man who was stopped by police because “they probably thought I was going to do a crime,” indicated he was cooperating with police instructions.

I was doing everything he told me and yet he still wants to get rough with me, you know, and then he called some more police to come assist him in getting rough with me. Oh it made me angry, and it made me want to get his gun and shoot him.

Another man acknowledged that he was out of control after being taken into custody by store security for shoplifting. When police arrived, he was already handcuffed and somewhat calmed down, yet the officer behaved as if he needed to be “taken down”:

The policeman [said], “Shut the fuck up.” Pow, he slaps me upside the head. All shit cut loose then, man, I must have….I jumped out of the seat but I was still handcuffed, trying to jump up and I was cursing him out, you know..I was really infuriated…because why would he do that? I was handcuffed.

As the above quotes suggest, the physical abuse reported by some participants was often accompanied by verbal abuse and disrespect, which seemed to be part of the overall negative experience. On its own, verbal abuse/disrespect contributed to negative evaluations of encounters and was tied to feelings of humiliation.

One woman, who was picked up for drug possession, felt she was treated in a dehumanizing way. She stated, “He treated me like, like I was trash, like I was a dope head, like I, I wasn’t part of the system. They laughed at me. They roughed me up, you know. I mean just because… They were humiliating me, you know.” A man whose encounter focused on a situation in which he was robbed recounted that the police accompanied him to the hospital to have his injuries treated. While this was a solicitous gesture, the participant felt offended by the officers’ questions, which were perhaps intended to assess his functioning and needs for assistance, yet nonetheless implied problematic assumptions about his mental illness:

And this is what I really couldn’t stand was that – ‘were you picked on in school or something?’ You know, ‘were you slow?’ ‘Why are you on these medicines?’ I felt humiliated. I just felt very, you know, helpless and made to… I was diminished. I was made to feel very small, you know. It felt lousy. It really did.

Just as having an opportunity for voice was linked to perceptions of fairness and more positive evaluations of police encounters, not having an opportunity to explain their view of the situation left participants feeling treated unfairly and to their evaluating the interaction negatively. Several participants described encounters in which they tried to tell their side of the story but were told to “shut up.” Others indicated they were not allowed to talk or were ignored when they tried. Those who indicated they were not given voice in an encounter generally felt they were treated unfairly and were dissatisfied with the encounter. This was true whether they were arrested or not. One woman described being stopped in a park with her boyfriend and searched, presumably for drugs. She tried to ask what officers were looking for and explain what they were doing at the park, “She wouldn’t let us talk. They just said they were going to put you in our file, you know, that we stopped you in the park. So basically they’re just hadn’t nothing better else to do than harass somebody.”

Another participant, who was accused of assaulting a woman and ultimately was arrested, felt that the officers who were called to the scene neither sought his account of the situation nor believed him when he tried to counter the accusation. Instead, they focused entirely upon the complainant’s side of the story:

I was trying to explain to them, you know, what was going on. All they did was they… You know, they were talking to her. They would say something to me, then they would like ignore me and say something, and talk to her, so, you know, they were like her private police, you know.

Advice for Police Officers

At the end of the interview, we asked all participants if they had advice for police officers about responding to calls involving people with mental illness. Several themes emerged from their responses. Participants want officers to allow them a chance to explain themselves and treat them like human beings. One woman indicated she would like to be able to explain herself, “It’s just they [should] talk to you and let you explain what’s going on and stuff, why a certain situation happened.” Several others wanted officers to understand that people with mental illness are human beings, and should be treated as such. In one man’s words, “Actually what I would tell the police about working with people that have mental health problems is to understand that they are human beings too.” This suggests that underlying the conception of being treated “like a human being” within the context of this asymmetrical power relationship is that the more powerful actor (the officer) takes the time to dialogue with the less powerful actor, and further, to explain his or her decisions rather than acting unilaterally to enforce order.

In addition, participants stressed that they wanted officers to be patient and to respond in a calm manner. One man indicated that staying calm was a source of security because it signals that the officer is there to help rather than to threaten the participant’s safety:

I would like the police to come and talk to me and keep me calm…..As long as they stay calm and talk to me. They do have a threatening appearance you know but as long as they are calm, I am calm, and I have nothing to fear because I know they are not going to hurt me.

Some participants want police officers to recognize or ask about mental illness. This would allow them to respond more effectively. As one participant stated, they could ask:

“Are you on any kind of medication” or “Are you seeing a psychiatrist or mentally ill?” They should ask that because common sense you see somebody acting crazy, when you want, wouldn’t you know, you know. They should, you know. That would probably alleviate a whole lot of all these police misconducts they got going on, suits happening against them right now.

Several participants specifically mentioned that officers should get special training to help them respond to people with mental illness more effectively, and keep situations from escalating. One participant indicated that he felt good that officers are getting trained. He stated, “Now they are training police to deal with people like us. They don’t have to always become forceful with them because all that will do is aggravate the problem, so that makes me feel good.”

Discussion

Two major themes emerged from our interviews with people with mental illness. First, the respondents are fearful of the police and second, the behavior of the police during these encounters affects the corresponding experiences and behavior of the respondents. This suggests that fairness and respect can affect the outcomes of police encounters with people with mental illness. Police actions do matter.

Our findings fit nicely within the procedural justice framework, and perhaps expand the content of some of the key elements. Participants often spontaneously discussed themes related trust/concern, dignity and voice when describing their interactions with police officers and these themes were clearly linked to their evaluations of the encounters in expected ways. Despite their negative general perceptions of the police, participants described many interactions that they experienced positively. In these encounters, participants described being treated with respect, dignity and concern. In some of the most positive contacts, participants described being treated with kindness. In these situations officers interacted on a more personal level, offering a cigarette or casual conversation that narrowed the status distance between the officer and participant. In procedural justice terms, such treatment affirms the person’s status as a valued member of the community rather than further marginalizing him or her (Lind and Tyler 1992). Not only is this experienced positively by the individual, it may enhance cooperation with the law in the moment and beyond (Paternoster et al. 1997; Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler 1990). Thus, procedurally just treatment could potentially reduce contact between persons with mental illness and the police, and when contact does occur, improve the outcomes for all.

Legitimacy is a concept often discussed in the procedural justice literature. Tyler (1997, 2004, 2006a, b) writes about global evaluations of the legitimacy of police use of authority as important to cooperation within specific encounters and suggests that procedural justice during personal encounters influences general views of the legitimacy of the police. In our interviews, participants spoke of legitimacy within the encounter more often than global evaluations of police legitimacy. They seemed satisfied with the encounter if they felt the police were acting legitimately within their role, or “just doing their job.” This was true even if components of procedural justice were absent. Similar to the findings of Carr and associates (2007), participants felt that the police had an important role in crime control and law enforcement and understand that they have a job to do.

As expected, verbal and physical abuse from police officers led to negative evaluations of encounters, as did the absence of voice. Among the encounters that were evaluated negatively were three that escalated to violence on the part of the participant. In a handful of other encounters, participants indicated they wanted to fight with police, but did not. They were able to consider the consequences in the moment and refrain from struggling with officers. Several situational characteristics may have contributed to whether these potentially violent situations escalated beyond thoughts of wanting to fight with police, while others did not. It appears that the combination of an already agitated person experiencing a mental health crisis and forceful and/or abusive treatment by police officers is a recipe for violence, whereas someone who is not in crisis is less likely to be provoked. It may also be that when officers are aware that they are approaching a person in crisis, their perception of risk may be heightened, thus eliciting a more forceful and rushed approach which in turn may further escalate the situation (Ruiz 1993). One man indicated, “They were more afraid of me than I was of them.” Fortunately, in many jurisdictions, officers are being trained to take a less forceful and rushed approach to responding to mental health crises as part of CIT programs. There is some evidence that CIT programs that include de-escalation training can reduce injuries to officers and persons with mental illness (Dupont and Cochran 2000).

It is important to stress that the participants in our study came into contact with police in a variety of ways. While participants reported contact with police during mental health crises, more often their contacts involved street stops and nuisance activity not directly related to their illness. Participants indicated that being stopped and asked for identification was a routine and was experienced as harassment. Many participants lived in nursing homes or single room occupancy hotels (SROs) and were unemployed. Thus, they spent much of their time in public spaces, making them more vulnerable to police scrutiny. This points to a failure of the mental health system rather than simply a policing issue. Increased housing options, employment services and opportunities, and spaces for people with mental illness to spend their time engaged in activity they find meaningful might be useful for reducing their vulnerability to police contact and further involvement with the criminal justice system by simply giving them someplace to be.

Conclusion

Our findings are consistent with the procedural justice framework and provide information that could improve police interactions with persons with mental illness. Clearly, less rushed and forceful approaches to persons in crisis could prevent situations from escalating. In less intense interactions, being respectful and kind and listening may lead to greater satisfaction on the part of the person with mental illness. Future research is needed to determine how procedural justice assessments relate to cooperation within these encounters and with the law more generally for persons with mental illness.

Study participants, like residents of low income, minority neighborhoods in general, tended to have unfavorable perceptions of the police (Reisig and Correia 1997). They expected to be harassed, treated unfairly, beat up, or even killed. Some had personally experienced abusive treatment, others reported knowing or knowing of people that had been beaten up and otherwise abused. Given their negative expectations, participants evaluated interactions positively if they simply were not abused. Being treated well, for example, with kindness, concern, dignity and voice, was icing on the cake. However, consistent with other studies of public perceptions of the police (cf. Skogan 2006) evaluating an individual interaction positively did not necessarily change participants’ overall negative perceptions of the police. One negative experience may be far more powerful than even several positive experiences. Thus, police departments have to work hard to improve general perceptions among persons with mental illness (and others), particularly in low income, minority neighborhoods where persons with mental illness often reside.

Currently, there are efforts across the country to improve police response to persons with mental illness. Many of these efforts are focused on mental health crises. Thus, it is important to note that people with mental illness come into contact with the police in a variety of ways, more often because of where they are rather than what they are doing. It will take more than law enforcement to address this problem. The mental health system and the community will need to work together to provide better housing and employment opportunities.

Notes

Note, by “success” we do not intend to objectively favor a particular outcome of a police contact over another. Rather, in this paper we hope to understand the perspective of persons with mental illness.

References

Caron, C., & Bowers, B. (2000). Methods and application of dimensional analysis: A contribution to concept and knowledge development in nursing. In B. L. Rodgers & K. A. Knafl (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications (pp. 285–319). Philadelphia: Saunders.

Carr, P., Napolitano, L., & Keating, J. (2007). We never call the police and here is why: A qualitative examination of legal cynicism in three Philadelphia neighborhoods. Criminology, 45(2), 445–480.

Cascardi, M. A., Poythress, N. G., & Hall, A. (2000). Procedural justice in the context of civil commitment: An analogue study. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 18(6), 731–740.

Census Database (2000) Demographics. http://www.chicagotribune.com/classified/realestate/communities. Accessed 5 March 2008.

Draine, J., Salzer, M., Culhane, D., & Hadley, T. (2002). The role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 53(5), 565–573.

Dupont, R., & Cochran, S. (2000). Police response to mental health emergencies—barriers to change. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 28, 338–344.

Greer, A., O’Regan, M., & Traverso, A. (1996). Therapeutic jurisprudence and patients’ perceptions of procedural due process of civil commitment hearings. In D. B. Wexler & B. J. Winick (Eds.), Law in a therapeutic key. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Kane, R. J. (2005). Compromised police legitimacy as a predictor of violent crime in structurally disadvantaged communities. Criminology, 43(2), 469–498.

Lidz, C., Hoge, S., Gardner, W., Bennett, N., Monahan, J., Mulvey, E., et al. (1995). Perceived coercion in mental hospital admission. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 1034–1040.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1992). Procedural justice in organizations. The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

Morabito, M. S. (2007). Horizons of context: Understanding the police decision to arrest people with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 58(12), 1582–1587.

National Council of State Governments. (2002). Criminal justice mental health consensus project. http://consensusproject.org/. Accessed 4 February 2008.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Bachman, R., & Lawrence, S. W. (1997). Do fair procedures matter? The effect of procedural justice on spouse assault. Law and Society Review, 31, 163–204.

Poythress, N., Petrila, J., McGaha, A., & Boothroyd, R. (2002). Perceived coercion and procedural justice in the Broward Mental Health Court. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 25, 517–533.

Reisig, M. D., & Correia, M. E. (1997). Public evaluations of police performance: An analysis across three levels of policing. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 20, 311–325.

Ruiz, J. (1993). An interactive analysis between uniformed law enforcement officers and the mentally ill. American Journal of Police, 12(4), 149–177.

Schatzman, L. (1991). Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to the grounding of theory in qualitative research. In D. R. Maines (Ed.), Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss (pp. 303–314). NJ: Aldine Transaction.

Skogan, W. G. (2006). Asymmetry in the impact of encounters with police. Policing and Society, 16(2), 99–126.

Skolnick, J., & Fyfe, J. (1993). Above the law: Police and the excessive use of force. USA: The Free Press.

Sunshine, J., & Tyler, T. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law and Society Review, 37(3), 513–547.

Terrill, W., & Paoline, E. (2007). Nonarrest decision making in police-citizen encounters. Police Quarterly, 10(3), 308–331.

Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Tyler, T. R. (1992). The psychological consequences of judicial procedures: Implications for civil commitment hearings. Southern Methodist University Law Review, 46, 401–413.

Tyler, T. R. (1997). The psychology of legitimacy: A relational perspective on voluntary deference to authorities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1, 323–345.

Tyler, T. R. (2004). Enhancing police legitimacy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 593, 84–98.

Tyler, T. R. (2006a). Legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 375–400.

Tyler, T. R. (2006b). Why people obey the law: Procedural justice, legitimacy, and compliance. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2000). Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. New York: Psychology Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2003). The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity and cooperative behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(4), 349–361.

Walker, S., & Katz, C. (2005). The Police in America: An introduction (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill.

Watson, A. C., & Angell, B. (2007). Applying procedural justice theory to law enforcement’s response to persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 58, 787–793.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant number R21MH075786 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors would like to acknowledge the hard work of Melissa Cosgrove, MSW and Theresa Vidalon, MSW who assisted with the interviews and data coding. We are grateful to the staff and members at Thresholds, Inc. who welcomed us and allowed us to conduct interviews in their space.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watson, A.C., Angell, B., Morabito, M.S. et al. Defying Negative Expectations: Dimensions of Fair and Respectful Treatment by Police Officers as Perceived by People with Mental Illness. Adm Policy Ment Health 35, 449–457 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0188-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-008-0188-5