Abstract

The obesity epidemic has widened the aims of prevention research to include the influence of local food environments on health outcomes. This mixed methods study extends existing research focused on local food environments by examining whether community members’ find food accessible. Data from food store audits and one-on-one interviews were analyzed. Results reveal that most of the food stores surrounding the three research sites were convenience stores and non-chain grocery stores; interviewees did not perceive these stores to be “real” food stores. Tobacco and alcohol products were more prevalent in the food stores than all varieties of milk, fresh fruits, or fresh vegetables. Food access varied by site in a manner that was designed to appeal to customers’ race, class, gender, or environment. Findings reveal that local food environments are reflections of social hierarchies. Unraveling the politics of space ought to be a part of broader efforts to promote the public’s health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

To understand the significance of space in health and health care, we cannot depend upon analysis of the spaces themselves, but must look at the meanings ascribed to the spaces, and how the spaces are used to facilitate behaviors and routines.

-Fox 1999 (p. 46)

Food, “a product and mirror of the organization of society” (Counihan 1999, p. 6), is at the center of this research, which focuses on both objective and subjective measures of the availability of food stores and food products within three communities in Nashville, TN. Over the past decade, a number of public health and medical researchers have investigated local food environments and explored the relationship between access to food and health outcomes. These studies are informed by ecological and population health perspectives, which challenge the biomedical model by avowing that health is produced through myriad factors including but not limited to individual-level characteristics such as biology, genetics, and behaviors.

Theories of Health

Ecological perspectives situate human choices and behaviors in direct relationship with the physical and social settings in which one resides, and maintain that individual behaviors are the product of personal characteristics, context, and the interaction between the two (Lewin 1935). Bronfenbrenner (1977) expanded the concept of ecological perspectives by identifying four spheres of influence affecting human health and development: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. These systems are often depicted as a series of concentric circles surrounding a person; the most proximal spheres are the microsystem and mesosystem, and the most distal are the exosystem and macrosystem.

The microsystem involves interactions between individuals and other people in their immediate settings, such as interactions within families and neighborhoods, between and among friends, and at work or school. The mesosystem focuses on interactions between various settings within the microsystem, such as when the family and neighborhood interact at a local convenience store. The exosystem involves the indirect influence of institutions on individual choices and opportunities. Policies and practices related to food-store marketing and development, for instance, represent an exosystem influence on populations. The macrosystem represents the overarching influence of economic, social, educational, legal, political, and cultural systems that show up in constructions such as capitalism, globalization, patriarchy, and racism.

Population health perspectives add complexity to the individual-environment interaction, and focus on exploring how and why health is socially produced (Evans et al. 1994; Kindig and Stoddart 2003; Whitehead and Dahlgren 1991). This approach to studying and addressing health is grounded in the growing body of public health research that suggests social conditions and social positions are important determinants of health (e.g., Cassel and Tyroler 1961; Haan et al. 1987; Kawachi and Berkman 2003; LaVeist 2002; Marmot and Syme 1976; Schulz and Mullings 2006). Population health perspectives are also rooted in the notion that all diseases have two causes—one pathological and the other political.Footnote 1 Accordingly, population health perspectives attempt to move beyond conventional explanations of morbidity and mortality, which view health as the absence of disease and as a function of individual factors (Evans et al. 1994; Institute of Medicine 2003; Shi and Singh 2005; Weber 2006). The resulting holistic view of health emphasizes a wide range of factors influencing health and wellbeing, including socio-cultural and economic conditions, living and working conditions, social networks, and individual behaviors, among other things (Dahlgren and Whitehead 1991).

Local Food Environments and Health

Concerned by the fact that over two-thirds of Americans are overweight or obese (Ogden et al. 2006), researchers and practitioners are beginning to acknowledge that health-promotion and obesity-prevention efforts focused on individual change alone are “ineffectual” because they do not take into account the contexts in which health behaviors and decisions are made (Jetter and Cassady 2006, p. 38). The obesity epidemic has, in turn, spurred many researchers to adopt ecological and population health perspectives, and has widened the aims of prevention research to include the influence of local food environments on health outcomes.

Results from these studies have found that local food environments vary by social context. Several studies have highlighted disparities in access to different types of food stores based upon the racial and economic composition of the community. Chain supermarkets such as Kroger or Publix—stores selling a wide variety of food items—tend to be located in areas that are predominantly populated by whites and by people representing middle or high levels of income whereas convenience stores and smaller, non-chain grocery stores are more common in communities predominately populated by racial and ethnic minorities and people living at or below the federal level of poverty (Baker et al. 2006; Chung and Myers 1999; Moore and Diez Roux 2006; Morland et al. 2002; Sloane et al. 2003).

The types of foods sold inside these stores also vary. A market basket survey found that non-chain grocery stores were much less likely to sell healthy food (e.g., whole wheat bread, skinless chicken) than chain supermarkets (Jetter and Cassady 2006). Another study found that non-chain food stores were up to two times less likely to sell fruits and vegetables than chain supermarkets (Chung and Myers 1999). In addition, foods sold in convenience or non-chain grocery stores are often cost more than the same product in chain supermarkets (Chung and Myers 1999).

These findings provide quantitative evidence that local food environments are not created equally. The quality of food stores and the products therein differ based on the social characteristics of people living near the stores. Areas of predominantly racial and ethnic minorities, and people with low levels of income have little or no access to food stores in general, and healthier food options in particular. The person-environment interaction in these locales may make it very difficult for people to adhere to obesity-prevention efforts, such as eating five fruits and vegetables per day, because they can not find these items. The resulting interaction may create health disparities.

The assessment of local food environments has expanded the definition of health; however, most of this research has been quantitative in nature. As a result, extant research documents differences in food access, but community members’ interpretations of access are missing. What does it mean to live in a community with little or no access to food? How does one make sense of the distribution of food stores in a community? What messages are conveyed through food stores or the lack thereof? Therefore, the purpose of this study is to extend existing quantitative research focused on local food environments by examining community members’ perceptions and interpretations of food access. Through a mixed-methods research approach involving food store audits and one-on-one interviews, this paper will construct a nuanced picture of food access.

Method

This research is part of a broader study focused on the promotion of health equity through the establishment of farmers’ markets at Boys and Girls Clubs (Freedman 2008). The analysis presented in this paper is focused on food store audit and interview data. This research was reviewed and approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Study Context

This research took place in three communities in Nashville, TN. Each community has a Boys and Girls Club, an organization with the mission “to enable all young people, especially those who need us most, to reach their full potential as productive, caring, responsible citizens” (Boys and Girls Clubs of Middle Tennessee 2008). The three Boys and Girls Clubs—Hopetown, Lincoln Court, and RidgetopFootnote 2—are located in noncontiguous census tracts in Davidson County, TN. These areas have higher rates of people living below the federal poverty level compared to Davidson County as a whole (see Table 1). Two of the Boys and Girls Clubs (Hopetown and Ridgetop) are next to public housing projects.

According to the 2000 decennial census, the socio-demographic characteristics of the census tracts surrounding the Boys and Girls Clubs differ by site (U.S. Census Bureau 2000). A gradient in median annual household income is evident. The census tract in which Lincoln Court is located has the highest annual median household income ($30,517). People living near Lincoln Court earn about one-third more per year than people living near Ridgetop ($21,936) and more than twice as much annually as those living near Hopetown ($14,714). The racial composition of the three sites also varies. The majority of the population residing in the census tract in which Lincoln Court is located identified their race as white (70.6%), whereas most of the residents near Hopetown indentified as black or African American (95.3%). The area near Ridgetop is the most racially diverse of the three sites, with 48.4% of the residents identifying as white and 42.7% identifying as black or African American.

Sampling and Recruitment

Food Store Audits

The source population for the food store audits included all food stores located within a mile radius of the three Boys and Girls Clubs. Shoppers could walk to stores within a mile of each Boys and Girls Club.

Food stores included supermarkets, local markets, and convenience stores. “Supermarkets” were defined as chain food stores that sell a wide variety of items, including food, medicine, toiletries, and alcohol. “Local markets” included non-chain food stores selling a wide variety of items. “Convenience stores” included chain or non-chain stores selling a limited variety of items including either food, medicine, toiletries, or alcohol. A total of 33 food stores were identified: 2 supermarkets, 10 local markets, and 21 convenience stores. Ninety-one percent of the food store owners permitted a food audit (30 of 33 stores). Three store owners refused to have their stores audited.

In-Depth Interviews

The source population for the in-depth interviews included anyone shopping at one of the three farmers’ markets that were established at the Boys and Girls Clubs as a part of the larger research endeavor (Freedman 2008). Purposeful and maximum variation sampling was used to select different types of interviewees (e.g., black, white, male, female, older, younger, community members, parent, etc.) (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Miles and Huberman 1994; Weiss 1994). This facilitated representativeness in the data analysis process (Miles and Huberman 1994). The interviews continued until interviewee responses related to the emergent themes became redundant; this point is often called “saturation” (Glaser and Strauss 1967).

Recruitment of interview participants took place at the farmers’ markets through posters and oral communication that described the purpose of the interviews, the time commitment, and the reimbursement amount ($20.00/interview). In-depth interviews were conducted with 20 individuals (Hopetown n = 4, Lincoln n = 7, Ridgetop n = 9); eleven with parents or guardians with children attending the Boys and Girls Clubs and nine with community members shopping at the farmers’ markets. Most interviewees were black or African American (90.0%), female (70.0%), had some college education or more (80.0%), and had an annual income of $39,999 or less (55%) (see Table 2).

Procedures

Food-Store Audits

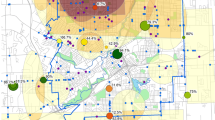

The food-store audits were conducted in May 2007. The audits were conducted by student researchers enrolled in a course at Vanderbilt University, all of whom completed a 4-h training focused on the food store audit process. Using geographical information system (GIS) software (ArcGIS, version 9.2), researchers created a map of each target area. This map represented all of the streets located within a mile of the three Boys and Girls Clubs. Each student team was assigned a target area and then traversed each street identified on their respective GIS maps for the presence of supermarkets, local markets, and convenience stores. For each store, students recorded the layout and flow of the store, the types of foods sold in the store, and whether or not the store sold alcohol or tobacco products. The types of foods examined included fruits, vegetables, dairy products, juices, meats, and breads. The food store audit used in this research was based on an inventory developed by the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UM-KC) Health Research Group.Footnote 3 In addition to conducting the food store audits, a photograph of each food store was taken.

In-Depth Interviews

In-depth interviews were conducted from June to August 2007. Interviews were open-ended, providing an opportunity to explore participants’ perceptions and interpretations of food access in greater detail, rather than closed-ended, “yes-or-no” interviews or surveys (Schensul et al. 1999). The interviews were semi-structured, open-ended, one-on-one, and focused on eliciting participants’ perspectives on the relationship between social contexts, social conditions, social positions, and access to healthy foods. Each participant was interviewed once. Interviews lasted between 45 min and two and one-half hours, including the time necessary to review and sign the informed consent form. The interviews were conducted at a location that was convenient for the participants, including fast-food restaurants, participants’ homes, the Boys and Girls Clubs, and over the telephone. All interviews were conducted by me and were tape-recorded for transcription.

The interview guide was a dynamic document, and new questions were added to the guide as new themes emerged (Weiss 1994). Because all interviewees were also customers at the farmers’ markets, the interviews typically began in light conversation about peoples’ experiences at the farmers’ markets. Next, participants were asked to describe the foods they consumed in the past 24 h and why they chose these foods. Participants were then asked to describe their most recent trip to the grocery store (e.g., Where did you go? What did you buy? What was the quality of the food in the store?). This was followed by questions about the food outlets located in participants’ neighborhoods (e.g., what types of food are sold at these outlets? how do the stores in your neighborhood compare to stores in other parts of town?). The last questions focused on the relationship between social position and access to food. Interviewees were asked to explore how these factors individually and collectively affect food access. For instance, how does one’s race, as well as the racial composition of a community, influence food access? Following each interview, participants completed a brief survey that focused on their demographic characteristics (see Table 2).

Analysis

Food-Store Audits

The food-audit data were analyzed using descriptive statistics in SPSS version 15.0. Frequencies were calculated to examine the types of food stores as well as the food items sold in the stores.

In-Depth Interviews

The qualitative data analysis approach was grounded in the thoughts, perspectives, and experiences of the interview participants. The analytic categories were derived directly from the data, rather than from predefined concepts or hypotheses (Charmaz 2001). Charmaz describes this process as an “interaction between the observer and observed,” thereby highlighting the influence of the observer’s worldviews, disciplinary assumptions, theoretical propensities, and research interests on data analysis (2001, p. 337). Thus, my transdisciplinary background in the fields of public health, community psychology, community development, and women’s and gender studies; my theoretical grounding in ecological and population health perspectives, and my social position as a white, middle-class woman living in Nashville all combine to inform the lens I applied to the qualitative data analysis process. I make no claims of being an “objective” or “neutral” observer. However, to keep my biases and perspectives in check, multiple methods, including two strategies for data collection and feedback sessions with the research team,Footnote 4 were employed to facilitate confirmability, dependability, credibility, transferability, and actionability—forms of validity frequently used by qualitative researchers—with respect to the resulting analysis (Miles and Huberman 1994).

Data analysis was a recursive process that began immediately after data collection. This was a back-and-forth process of collecting and analyzing, reviewing and discussing, and asking and re-asking questions of participants and the data. Once data were transcribed, I began listening to and reading the data in an effort to find regularities, patterns, and topics. Words and phrases that represented topics and patterns became the coding categories. Once preliminary coding categories were devised, they were assigned to units of data (e.g., word, sentence, or paragraph). This was an iterative process, in which the data were read through again, old categories were modified, and new categories were developed. This process was facilitated through the use of NovaMind 4 Platinum, an electronic tool for brainstorming and organizing information, as well as through Atlasti version 5.2, a qualitative data analysis software program. I managed the coding and data interpretation process. However, I met with the research team every week to review the coding categories and emergent themes.

Results

Availability of Food Stores Near Boys and Girls Clubs

Thirty-three food stores were identified within a mile of the three Boys and Girls Clubs (see Fig. 1). Almost two-thirds of the food stores were convenience stores (n = 21). Only two supermarkets were located in the three communities. Ten local markets were found within a mile of the three Boys and Girls Clubs.

The distribution of food stores varied across sites. Two of the Boys and Girls Clubs had a supermarket available within a mile, indicating physical access to a wide variety of food items. Hopetown, however, did not have a supermarket nearby. This was unexpected, since the population density of Hopetown’s census tract is substantially greater than those of census tracts for Lincoln Court and Ridgetop Boys and Girls Clubs. The supermarket-to-resident ratio was 1:2,383 for Lincoln Court and 1:1,974 for Ridgetop. Based these trends, it was predicted that the area near the Hopetown Club would have between two and three supermarkets. However, the supermarket to population ratio near Hopetown was 0:6,850.

These communities had more convenience stores than all other types of food stores. There was approximately one supermarket or local market for every two convenience stores in the areas near the Boys and Girls Clubs. This ratio is higher than that found in a national study of food store access, which identified a 1:1 ratio between supermarkets/local marketsFootnote 5 and convenience stores in low-wealthFootnote 6 communities (Morland et al. 2002).

When asked to describe the types of food stores available near the Boys and Girls Clubs, two types of responses emerged. First, many participants indicated there were no food stores in their community, revealing that interviewees did not consider the local markets or convenience stores to be “real” food stores. Instead, they described “good” food stores as being “way out” and “far away.” Over half of the interviewees reported that they were not satisfied with the food stores in their neighborhoods. The following excerpt from an interview with an African American woman focuses on her views of the food stores in Hopetown:

I mean, you’re not fixing to find any foods or anything in the convenience store. It’s a horrible thing, you know, for those who don’t have it [transportation], because they are forced to go to one of those convenience stores [in Hopetown]. …They [the stores] don’t have real food over there. You know, I mean, most of the time, the food is going to be outdated. So none of it [the food] would be good.

This participant indicated that if she had to rely on the local convenience stores to purchase foods for her family, then her “diet would probably be dead.” She followed this comment by saying, “You’re probably looking at about twenty pounds more of me” if she did not have private transportation to travel to food stores located in other parts of the city.

The products available in the local food stores were also described as being “over-priced” and “higher [in price] than the bigger grocery stores.” One-fourth of the participants reported that the “convenient” part of a “convenience store” simply means that “everything is a dollar more” than the same product in an “inconvenient” location.

Availability of Healthy and Unhealthy Products

In addition to examining the types of food stores located in the areas surrounding the three Boys and Girls Clubs, the auditors also documented the availability of healthy and unhealthy products for purchase in the stores. The next analyses are limited to the 30 food stores in which an interior audit was permitted.

Access to “Healthy” Food Products

First, the types of fresh fruits and vegetables available for sale at the food stores were assessed (see Table 3). Fresh fruits were only available on a limited basis in all three of the communities; 70% of the food stores did not sell at least one fresh fruit. The most common fresh fruits for sale in the food stores were oranges (23.3% of stores sold oranges), bananas (20.0%), and apples (20.0%) and the least common were grapes (6.0%) and grapefruit (6.0%). Fresh fruits were most abundant, though certainly not overwhelmingly available, near Lincoln Court, with multiple stores selling fresh bananas, apples, oranges, and peaches. One food store near Ridgetop (Kroger) sold a wide variety of fresh fruits. Access to fresh fruits was limited in the Hopetown area; the only fresh fruits sold near the Hopetown Boys and Girls Club were bananas, apples, and oranges.

Fresh vegetables were found less often than fresh fruits. More than 80% of the food stores did not sell at least one fresh vegetable. The most prevalent vegetables sold in the communities were lettuce (13.3% of stores sold lettuce) and tomatoes (13.3%). Once again, food stores near Lincoln Court sold the greatest amount of fresh vegetables, while the area near Hopetown had the least access to fresh vegetables for sale in the community. Tomatoes were the only fresh vegetableFootnote 7 available for sale within a mile of Hopetown.

In the few instances when fresh produce was available at local food stores, participants indicated that the quality of these items was less than ideal. An African American man from the Lincoln Court site addressed this concern by stating that fresh fruits and vegetables sold at a local chain supermarket were “not very good.” He continued to say:

…you buy like a pack of oranges [at the local chain supermarket] and you’ll see some that have mold on them. The same with strawberries. The selection, it wouldn’t be as good or they would have only a few items where [name of chain supermarket in another area] would have a wide layout and would also have the option to have organics.

Due to the limited variety and low quality of the produce, about one-third of the participants stated that they would not go to a food store located in their community to buy fresh fruits and vegetables. However, some indicated that they would buy canned produce from these stores.

In addition to examining access to fruits and vegetables, the availability of milk products was examined. Across the three sites, over two-thirds of the food stores sold milk. Whole milk was most commonly found in the food stores, whereas low-fat and skim milk were found substantially less often. Skim milk was not available for purchase in the area near Hopetown.

Access to “unhealthy” products

Finally, we examined the availability of tobacco and alcohol products in the food stores. These products were by far the most common items for sale in the community. Tobacco products (e.g., cigarettes, chewing tobacco, cigars) were available for purchase in 90% of the food stores, while alcohol products (e.g., beer, wine, liquor) were available in 80% of the stores. In the areas surrounding the Boys and Girls Clubs, tobacco and alcohol products were more prevalent than all varieties of milk, fresh fruits, or fresh vegetables.

Tobacco and alcohol products were most prevalent in the area near the Hopetown Club, with 100% of the stores selling tobacco products and 87.5% selling alcohol products. By contrast, few food stores near Hopetown sell healthy food items, such as fresh fruits, vegetables, and low-fat milk options.

Healthy Food is Far Away

Feedback from interview participants corroborated the food mapping data. There was consensus amongst the interviewees that the local food stores sold limited or no healthy products. When describing the types of foods sold within his community, an African American man from Ridgetop stated:

Far as fruit, there ain’t no fruit there [at the local convenience store]. I don’t remember seeing no kind of, you know, like oranges, bananas, apples, tangerines, peaches; I don’t see none of that down there. They ain’t got no fruits or nothing.

Instead of selling fruits or other types of healthy foods, the local food stores were described as being stocked with a wide variety of potato chips, candy, cold drinks, cigarettes, and beer. The following excerpt from an interview with an African American woman from Ridgetop illustrates participants’ perceptions of the foods sold within local food stores. This excerpt is related to the convenience store located just one block away from the interviewee’s home:

The little corner store [in the Ridgetop neighborhood], I’ve been in there a couple of times, and it’s smelly in that store. He has nothing to offer for me in the corner store. That’s the nearest place, and then he doesn’t have a lot to offer in that store. Cigarettes and beer I think are his two biggest selling items, because you see people coming out of there with beers in a sack and cigarettes. He has no fresh vegetables in there that I know anything about. And, this is it. You can’t even go buy an onion out of there. You can’t go there to get an onion or a head of lettuce.

The conclusion of this excerpt—“You can’t go there to get an onion or a head of lettuce”—reveals a deeper message about access to healthy foods in these communities. This participant is indicating that access to food is limited not only for fresh fruits and vegetables with a short shelf life (e.g., lettuce) but also for foods with a longer shelf life (e.g., onions). As one interviewee stated, one would therefore be in “hard luck” to find any fresh fruits and vegetables for sale in the local food stores.

Intersectionality of Food Access

Food audit and interview data revealed that access to healthful foods was associated with a variety of intersections. In the spatial sense, the intersections of streets and crossroads influenced food access. Some streets had food stores, while others did not. The people residing on various streets at various intersections were, in turn, vessels comprised of a range of social intersections—intersections of race and class and gender and age and so on.Footnote 8 Spatial intersections were related to socio-political intersections. Both intersected to influence access to food; Hopetown, the community with (1) the highest number of blacks or African Americans, (2) the lowest median household income, and (3) the highest number of single, female-headed households had the least access to fresh fruits and vegetables but the most access to tobacco and alcohol. Hopetown is one example of social relations of power related to space, race, class, and gender intersecting.

The intersectionality of food access was a common theme among interview respondents. Participants often referred to the ways that local food environments are “raced” and “classed” and “spaced.” An African American woman from Hopetown, for instance, responded to a question about differences in food access across various communities by saying, “…it’s all geographical. The good stores are in the better areas of town.” She followed this statement by saying that she didn’t want to “pull out the race card” to explain differences in food access, but then proceeded to describe the quality in freshness and goodness of foods sold in predominantly African American and/or low-income communities compared to those sold in stores located in predominantly white and/or higher income areas of town.

About one-fourth of the interviewees perceived local food environments to be related to intersections between race and space. For some participants, this relationship was quite easy to notice and describe, because segregation among food stores was understood to be a byproduct of broader systems of racism and oppression. An African American woman from Lincoln Court, for instance, frankly stated:

I’m sure that a predominantly black neighborhood might have food that’s not as healthy or you know, as fresh as somebody else’s. It wouldn’t shock me. You know? I mean, you know, things are better but racism is not dead. That’s just life.

For others, however, perceptions of food access as a raced phenomenon became more pristine throughout the interview process. The following excerpt highlights the thinking process of an African American woman from Ridgetop as she reflected on the relationship between the racial composition of a community and access to food:

Ridgetop doesn’t have anything within walking distance, again, grocery-store wise. There’s nothing in walking distance. I’m thinking of the communities around here…. [she names several different communities]…. you don’t…there’s nothing…there’s no Kroger or Piggly Wiggly or Food Lion in walking distance of those communities, and those are predominately African American and minority neighborhoods. You have to go onto the main streets, which you do need a vehicle or a bus pass to get to. So, you see what I mean? If you don’t have a car or you’re on a bus pass, you’ve got to think about all the different obstacles you have to go through just to get to a store that would even sell fresh fruits and fresh vegetables.

This interviewee detailed a pattern in food access such that “minority communities” tended to be in areas with little or no access to stores selling healthy food products. People located in these types of communities would therefore need to cross many “different obstacles” as they transgressed the boundaries of community, crossing spatial and social intersections, to locate fresh fruits and fresh vegetables.

In addition to viewing local food environments as being raced, about one-fourth of the interviewees described them as also being classed. Local food environments were perceived to mirror the social class of a community, as the following excerpt from an interview with an African American woman from Hopetown reveals:

Well, the neighborhood I live in is more low…it’s in a low-income place, because it’s subsidized. There’s not many good market stores that’s exactly where I am. So most of the low-income places is not going to have, per se, a nice little store to get fresh foods, and even get food that’s of value in money, you know.

A white woman from Lincoln Court reported that high-, middle-, and low-income communities “can have the same store, but it’s not stocked the same. They’re all stocked differently.” She followed this statement by saying that she was “better off” going to food stores in high-income communities—stores near her work—than shopping at stores in the Lincoln Court community. Others reported that low-income communities do not have chain supermarkets or specialty grocery stores.

Discussion

This study provides a nuanced picture of the local food environment of a specific context: three Boys and Girls Clubs in Nashville, TN. This picture includes both objective and subjective assessments of food access. An objective count of food stores located within a mile of the three Boys and Girls Clubs revealed higher levels of access to convenience stores and non-chain grocery stores than to chain supermarkets. Over 90% of the food stores established near the Boys and Girls Clubs were convenience stores or non-chain grocery stores. In other research, these types of stores have been found to sell healthy food options substantially less often compared to chain supermarkets (Chung and Myers 1999; Jetter and Cassady 2006). In addition, convenience stores and non-chain grocery stores often sell foods at a higher price than the same product in a chain supermarket (Chung and Myers 1999). The results of this study parallel these previous findings. Less than one-third of the food stores located near the Boys and Girls Clubs sold at least one fresh fruit. Even fewer food stores sold at least one fresh vegetable. In contrast, tobacco and alcohol products were available for purchase at 90 and 80% of the stores, respectively.

Although 33 food stores were identified through the food audit process, interviewees frequently did not acknowledge the presence of any food stores in their communities. In their opinion, no “real” food stores existed in the areas near the three Boys and Girls Clubs. Subjective interpretations of food access revealed that physical access to food was essentially nonexistent in these communities. When stores were acknowledged in participants’ local food environments, these stores were often described as being less than ideal. The stores were considered to be unclean and expensive, offering a limited selection of healthy food items but a wide array of unhealthy products.

Patterns in food access existed amongst the three sites. Although access to healthy foods was limited across all three sites, the Boys and Girls Club located in the census tract with the most people of color, people living in poverty, and single, female-headed households had the least access to healthy foods, but the most access to alcohol and tobacco products. Interview participants also highlighted the inverse relationship between “good food” and socially marginalized populations and communities. Interviewees reported that food stores vary from one community to the next; however, these variations were not understood to be random. Instead, participants invoked racial and economic factors to explain the quality of local food environments. These findings corroborate extant research suggesting that heterogeneities in local food environments are a function of the racial and economic make-up of a community (Baker et al. 2006; Chung and Myers 1999; Moore and Diez Roux 2006; Morland et al. 2002; Sloane et al. 2003).

Food mapping and interview data corroborate findings from other studies revealing that where one lives is strongly associated with one’s ability to access and ultimately consume healthy foods. The notion that one’s environment influences behaviors and choices is not novel. The reciprocal relationship between environments and human behaviors is central to scholarship informed by an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner 1977; Kelly 1966; Lewin 1935) and has led some scholars to argue: “It is not the nature of health behaviours, but the contexts in which they take place (where, when, and with whom), that need to be analyzed” (Morrow 1999, p. 758, emphasis in original).

Ecological perspectives shift the burden of public health concerns onto places rather than people in an effort to move beyond individually oriented understandings of health, and thus purport that where you are in society has equal or greater influence on behaviors, choices, and outcomes than who you are. Data from this research, however, reveal that this view of places and peoples is far too neat and narrow. Food access was found to be related to the intersectional and entangled relationship between where and who you are. Food access in the Hopetown, Lincoln Court, and Ridgetop communities was not only related to their geographic coordinates, but also and perhaps to a greater extent to their social coordinates. The “where” and the “who” in these spaces were mutually constitutive and dynamic. Local food environments represented “physical concretizations of power” (Mitchell 2000, p. 125) located on the socially constructed gridlines of race, class, and gender.

Accordingly, research and action striving to improve health outcomes by addressing local food contexts ought to consider the systems and relations of power produced and reproduced through these spatial locations. A focus on the presence or absence of food stores as key determinants of health does indeed represent a shift away from individually oriented understandings of health and wellbeing, but the results from this research indicate that this may only be the first step as we move “upstream” in our analysis (Cohen and Chehimi 2007). As we begin to explore the causes of the causes, research and practice focused on improving the health of the public may, for example, begin to examine housing policies and practices, and the ways that they contribute to the creation of segregated communities. We may also identify and deconstruct the ways that various forms of oppression, such as racism, classism, or sexism unwittingly influence access to food (Jones 2002).

Future research is also needed to examine the messages conveyed by and through local food environments. This new line of research may explore the messages transmitted through food stores that are raced and classed and gendered and spaced into hierarchies of quality and goodness. It may also examine the ways that these differences in space influence peoples’ health and well-being. Perhaps most important, studies ought to investigate strategies for unraveling the politics of space and begin to redress social injustices related to food access, or lack thereof.

Limitations

There are three main limitations related to this research. First, like all research that does not use random sampling, results from this study are not generalizable to all populations (Babbie 2001). In particular, since data were collected at Boys and Girls Clubs located in an urban setting in the southeastern region of the United States, findings may not apply to populations without these types of youth-serving organizations or communities outside this region. Second, the sample size for the Hopetown site was small compared to the other sites. This may limit the representativeness of responses from the Hopetown site. Finally, there is the chance that researcher and/or participant bias influenced the collection and analysis of the qualitative data. The use of multiple methods for collecting data was one strategy for addressing this concern. In addition, biases were examined on a regular basis through ongoing meetings with the research team.

Conclusion

This research provides quantitative and qualitative evidence supporting the notion that food environments differ by community. Although all humans have similar needs for nutritious food, physical access to healthful food products differs by social location. These differences were found to be patterned according to the socio-demographic characteristics of people residing in a community. Disparities in local food environments represent one stone in the sea of influences affecting the health of the public, and the ripple effect produced by these differences may contribute to health inequities.

Notes

Physician-activist Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902) said that all diseases have two causes, one pathological and the other political.

Hopetown, Lincoln Court, and Ridgetop are pseudonyms for the three research sites.

I received a copy of the inventory from Dr. Paul Speer. The lead investigators of the UM-KC research project were Walker C. Poston, C. Keith Haddock, and Joseph Hughey.

The research team was comprised of three research assistants and five faculty advisors. Members of the team had diverse disciplinary backgrounds, representing psychology, nursing, sociology, public health, and community development. Half of the team members identified their race as black or African American, and the remaining as white or Caucasian.

In this study, the term “grocery store” was used instead of local market.

Morland et al. (2002) determined wealth by calculating the median value of homes in the census tracts included in the study.

By definition, tomatoes are fruits. However, they are commonly referred to as vegetables. In this research, tomatoes were categorized as “vegetables.”

References

Babbie, S. (2001). The practice of social research (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Baker, E., Schootman, M., Barnidge, E., & Kelly, C. (2006). The role of race and poverty in access to foods that enable individuals to adhere to dietary guidelines. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3(3), 1–11.

Boys and Girls Clubs of Middle Tennessee. (2008). Retrieved June 17, 2008, from http://www.bgcmt.org/main_sublinks.asp?id=4&sid=81.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531.

Cassel, J., & Tyroler, H. A. (1961). Health status and recency of industrialization. Archives of Environmental Health, 3, 25–33.

Charmaz, K. (2001). Grounded theory. In R. M. Emerson (Ed.), Contemporary field research (pp. 335–352). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press Inc.

Chung, C., & Myers, S. L. (1999). Do the poor pay more for food? An analysis of grocery store availability and food price disparities. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 33(2), 276–296.

Cohen, L., & Chehimi, S. (2007). Beyond brochures: The imperative for primary prevention. In L. Cohen, V. Chavez, & S. Chehimi (Eds.), Prevention is primary: Strategies for community well being (pp. 3–24). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Counihan, C. M. (1999). The anthropology of food and body: Gender, meaning, and power. New York: Routledge.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and anitracist policies. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 13, 9–167.

Dahlgren, G., & Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm: Institute of Futures Studies.

Evans, R. G., Barer, M. L., & Marmor, T. R. (Eds.). (1994). Why are some people health and others not? The determinants of health of populations. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Fox, N. J. (1999). Beyond health: Postmodernism and embodiment. New York: Free Association Books.

Freedman, D. A. (2008). Politics of food access in food insecure communities. Unpublished Dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Haan, M., Kaplan, G. A., & Camacho, T. (1987). Poverty and health: Prospective evidence from the Alameda Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 125(6), 989–998.

Institute of Medicine. (2003). The future of the public’s health in the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Jetter, K. M., & Cassady, D. L. (2006). The availability and cost of healthier food alternatives. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(1), 38–44.

Jones, C. P. (2002). Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. In T. A. LaVeist (Ed.), Race, ethnicity, and health (pp. 311–318). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (Eds.). (2003). Neighborhoods and health. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kelly, J. G. (1966). Ecological constraints on mental health services. American Psychologist, 21, 535–539.

Kindig, D., & Stoddart, G. (2003). What is population health? American Journal of Public Health, 93(3), 380–383.

LaVeist, T. A. (Ed.). (2002). Race, ethnicity, and health: A public health reader. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lewin, K. (1935). A dynamic theory of personality. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Marmot, M., & Syme, S. (1976). Acculturation and coronary heart disease in Japanese-Americans. American Journal of Epidemiology, 104(3), 225–247.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Making good sense: Drawing and verifying conclusions. In M. B. Miles & A. M. Huberman (Eds.), Qualitative data analysis (pp. 245–280). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mitchell, D. (2000). Cultural geography: A critical introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Moore, L. V., & Diez Roux, A. V. (2006). Associations of neighborhood characteristics with the location and type of food stores. American Journal of Public Health, 96(2), 325–331.

Morland, K., Wing, S., Diez Roux, A., & Poole, C. (2002). Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22(1), 23–29.

Morrow, V. (1999). Conceptualising social capital in relation to the well-being of children and young people: A critical review. Sociological Review, 47(4), 744–765.

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Curtin, L. R., McDowell, M. A., Tabak, C. J., & Flegal, K. M. (2006). Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Journal of the American Medical Association, 295(13), 1549–1555.

Schensul, S. L., Schensul, J. J., & LeCompte, M. D. (1999). Essential ethnographic methods: Observations, interviews, and questionnaires. Walnut Creek: Rowman & Littlefield.

Schulz, A. J., & Mullings, L. (2006). Gender, race, class, and health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Shi, L., & Singh, D. (2005). Essentials of the U.S. health care system. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Sloane, D. C., Diamant, A., Lewis, L. B., Yancey, A. K., Flynn, G., Nascimento, L. M., et al. (2003). Improving the nutritional resource environment for healthy living through community-based participatory research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18, 568–575.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Decennial census. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Weber, L. (2006). Reconstructing the landscape of health disparities research: Promoting dialogue and collaboration between feminist intersectional and biomedical paradigms. In A. J. Schulz & L. Mullings (Eds.), Gender, race, class, and health: Intersectional approaches (pp. 21–59). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Weiss, R. S. (1994). Learning from strangers: The art and method of qualitative interviews. New York: The Free Press.

Whitehead, M., & Dahlgren, G. (1991). What can be done about inequalities in health? Lancet, 338(8774), 1059–1063.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants from the Baptist Healing Trust, Vanderbilt University Center for Community Studies, and Vanderbilt Center for Health Services. Gratitude is extended to the participants in this study and to my research advisors: Paul Speer, Craig Anne Heflinger, Monica Casper, Ken Wallston, Marino Bruce, Shavaun Evans, Shacora Moore, and Courtney Williams. Thank you to Sharon Shields and her students for their assistance with the food auditing process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freedman, D.A. Local Food Environments: They’re All Stocked Differently. Am J Community Psychol 44, 382–393 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9272-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-009-9272-6