Abstract

Income volatility appears to be increasing especially among lower income workers. Such volatility may reflect the ongoing shift of economic risk from employers to employees as marked by decreasing job security and employer-provided benefits. This study tests whether absolute volatility or downward volatility in income predict depression controlling for prior depression. A sample (n = 4,493) from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) with depression (CESD) measured at age 40 and prior depression measured eight to 10 years earlier was utilized. Downward volatility (frequency of income loss) was positively associated with depression; adjusting for downward volatility and other covariates, absolute volatility was negatively associated with depression. An interaction indicated a positive association between downward volatility and depression only when absolute volatility was high. These findings apply to respondents in a narrow age range (30 s) and the results warrant replication to identify the mediators linking absolute volatility and income loss to depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Income Volatility and the Shift of Economic Risk

Many studies have linked low income (e.g., Martikainen et al. 2003) and adverse employment change (e.g., Dooley 2004) to poor physical or mental health. This study examines the less explored construct of income volatility and tests the hypothesis that it predicts poor psychological health, specifically depression.

Income volatility refers to year-to-year change in earned income typically of the individual worker or for the family as a household unit. Economists often aggregate such individual-level measures of volatility by averaging over persons within temporal (e.g., series of five-year intervals) or spatial units (e.g., various countries). Such analyses can monitor trends over time or differences between economies. Recent research of this type indicates that aggregate income volatility has been rising in the United States (Gottschalk 1994; Hacker 2004; Moffitt 2002; Stevens 2001).

If income volatility threatens health or well-being, these increases raise the importance of understanding its public health consequences. However, income volatility is not necessarily harmful. The absence of year-to-year income change would mean that economic status is frozen with no opportunity for upward mobility. Although some volatility is essential for a dynamic society, conventional wisdom views the recent level of income volatility as harmful, e.g., via its link to the increasing gap between high and low income groups (Hacker 2004). The combination of upward and downward income changes could create unpredictability in income and savings, and hamper planning for the future. Moreover, income volatility appears to increase following such known stressors as job displacement (Stevens 2001) and may also be linked to changes in wages or hours in the absence of employment transitions (Gottschalk 1994). Thus, income variations can reflect both unemployment/re-employment transitions and shifts into and out of economically inadequate employment (e.g., poverty wages or involuntary part-time work). Both of these forms of underemployment (unemployment and economically inadequate employment) have been linked to increased depression (Dooley 2004).

Income volatility appears in a larger context. Recent attention has focused on the increasingly risky relationship that individuals have with their sources of income (e.g., under such rubrics as precarious employment, earnings uncertainty, and job insecurity). Employees decreasingly enjoy the standard relationship with their employers that assured them of full-time work in a steady job that lasted until retirement, and that often included such benefits as health insurance and employer-supported pensions. Work is being repackaged as outsourced jobs with payment for a defined task or product without assurance of future work (Dooley 2004). As a consequence, workers report rising perceived job insecurity (Schmidt 1999), which is linked to adverse psychological outcomes (De Witte 1999; Dooley et al. 1987; Sverke 2002).

Rising income uncertainty extends beyond workers. With the US welfare reform of 1996, welfare recipients saw their benefits become time limited with greater pressure to enter the labor force with its rising risks. Retirees from some large American corporations have seen their pension payments reduced as part of the cost cutting necessary for these companies to avoid bankruptcy. At the same time, politicians are raising concern about the reliability of social security. In sum, economic risks are being shifted to individuals from institutions such as corporations and governments.

Unfortunately, we know little about the health consequences of this shift of economic risk. We propose the variable of income volatility as a plausible operationalization of this phenomenon. Economic research has documented the rise in income volatility in recent years, but few studies have addressed the relationship of income change to any indicator of well-being and fewer still to the specific outcome of psychological depression.

Depression is a plausible effect of any stress resulting from income volatility. Moreover, the worldwide economic and societal burden of depression is substantial. From an economic standpoint, across 28 European nations, the direct cost of depression was estimated at 42 billion dollars in 2004 when considering outpatient care, drug costs and hospitalization, which corresponds to approximately 1% of the total economy of Europe (Sobocki et al. 2006). The economic burden of depression in the United States has been fairly stable between 1990 and 2000 with total cost estimated at 83.1 billion dollars in 2000 (Greenberg et al. 2003). Furthermore, from a societal standpoint, 109.7 million working days were lost due to depression in the United Kingdom (Thomas 2003), and costs to the workplace were estimated at 51.5 billion in the United States in 2000 (Greenberg et al. 2003). European nations reported depression as being the most costly mental disorder in Europe (Sobocki et al. 2006), and suicide-related mortality costs were estimated at 5.4 billion dollars in the US in 2000 (Greenberg et al. 2003).

From an individual perspective, events that cause feelings of loss and disappointment, especially those with possible long-term consequences have been associated with depression (Brown 1978). Researchers have linked specific events such as job loss (Montgomery et al. 1999), inadequate employment (Dooley et al. 2000) and welfare transitions (Dooley 2002) to increases in depression. Other researchers have linked changes in depression to change in family structure such as parenthood (Evenson 2005) or marital status (Frech 2007) as well as chronic environmental stressors such as neighborhood disorder (Hill et al. 2005).

Absolute versus Downward Volatility

Most of the economic research on income volatility has defined it as absolute change, i.e., variability without regard to the direction of change. The view that change per se might be harmful has a long tradition traceable to the nineteenth century sociological analysis of Durkheim (1966). He argued that any change, including economic booms, could undermine social cohesion. Breaking down the norms of behavior and social relationships could in turn leave individuals with a sense of alienation or anomie. He tested this theory by linking absolute economic change and suicide, both measured in the aggregate. This finding has been replicated in more recent data using modern econometric methods (Pierce 1967).

A more psychological mechanism by which change per se might produce distress comes from the stressful life event literature. The earliest approach summed both desirable and undesirable life changes (Holmes 1967) as representing potential demands for adaptation on the part of the individual. Thus, all events had the potential to exhaust the adaptive resources of the individual and, in turn, lead to adverse outcomes.

In contrast, the more intuitive view suspects that downward income changes would produce more stress than upward changes. Thus, absolute volatility might be associated with distress only because it includes downward change, and downward volatility would better predict distress than would change per se. Supporting this view, some aggregate time-series research has found that signed rather than absolute economic change measures better predicted such outcomes as depression (Catalano 1977). Similar findings have emerged from individual-level life event studies (Vinokur 1975). For example, one study found that undesirable economic life events predicted psychological symptoms better than their desirable economic counterparts (Dooley et al. 1987).

Prior Studies of Income Change and Well-Being

Most studies of income change and well-being have analyzed the link from family income to child development and well-being as mediated by parental functioning and home environment. Such studies usually focus on income loss between two time points as distinct from absolute income change, and when income increases are noted, they are usually associated with favorable change in the children (Dearing et al. 2001). These studies typically find significant adverse effects on lower income (vs. no effects in higher income) children including their social behavior (e.g., Dearing et al. 2001) and cognitive stimulation (Votruba-Drzal 2003). In contrast, others have found income variability unrelated to child well-being, perhaps because of insufficient variation in the income measure (Mistry et al. 2004). In adult samples, reductions in income have been shown to have a greater impact on physical health than increases in income (Benzeval 2001).

Besides paying little attention to absolute income change, these studies rarely measure the outcome of interest here, namely depression. However, one study of two-parent families found that income decreases were associated with increased economic pressure and hardship adaptations that were linked to negative changes in emotional health (Eldere et al. 1992). Income loss particularly affected fathers whose increased depression and hostility, in combination with the families’ economic pressures, were associated with aggressive behavior and depression in the children.

Hypotheses

To fill the void of research on income volatility and depression, this study tests three hypotheses. The first predicts that individuals who experience more absolute volatility in their incomes will report higher levels of depression. This test will control for likely confounding variables including prior depression that may operate by reverse causation to affect employment changes and income variation (Dooley 2004).

The second hypothesis predicts that individuals who experience more frequent episodes of income loss (downward volatility) will report higher levels of depression. Again this test will control for potential confounding variables such as income level and prior depression.

The third hypothesis predicts that downward volatility and absolute volatility will interact to affect depression. Support for this hypothesis stems from the stressful life events literature which suggests that both desirable and undesirable life events can have adverse mental health effects (e.g., Kessler 1997) as well as the intuitive view that high absolute volatility, when combined with frequent downward income change, should have more severe mental health effects. Specifically, when the magnitude of absolute volatility is high, the frequency of downward volatility should have strong positive association with depression. But when absolute volatility is low, indicating a relatively static income, the association between frequency of income loss and depression should be smaller in magnitude. That is, income losses of small magnitude should be less consequential than those of large magnitude.

Based on hints in the literature of interactions involving income change, other possible moderators of the volatility effects will be evaluated. For example, those in lower income groups might feel the adverse effects of volatility more acutely than their higher income counterparts due to fewer buffering resources such as accumulated wealth.

Methods

Sample

The National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79) was used to evaluate the relationship between income volatility and depression. The survey, under the administration of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, was started in 1979 with a sample of 12,686 individuals who were born in the United States between January 1, 1957 and December 31, 1964. Interviews were conducted annually through 1994 and every other year thereafter. The NLSY79 consists of three subsamples (Center for Human Resource Research 2002): (1) a cross-sectional sample of 6,111 designed to be representative of people aged 14–21 years living in the US in 1979; (2) a supplemental sample of 5,295 designed to over-sample Hispanic, African American and economically disadvantaged non-African American, non-Hispanic youth living in the US; and (3) a sample of 1,280 designed to represent youths enlisted in the four branches of the military as of September 30, 1978. The NLSY79 reports a 77.5% retention rate as of 2002 (Center for Human Resource Research 2002).

Beginning in 1998, the NLSY79 included an extra module for respondents aged 40 years and over (referred to as the NLSY 40+ Health Module) to collect health data on the panel as it entered middle age. A total of 6,518 respondents were 40 years or older at the 2000, 2002, and 2004 interviews. The CES-Depression scale (CESD) (Radloff 1977) was administered in the survey year when the respondents turned 40 years (or 41 years if a respondent turned 40 in the previous non-interview year) and was available for 6,429 of these respondents. Baseline CESD came from the 1992 interview (8 years earlier) for respondents who were 40 years old in 1999 or 2000, from the 1994 interview (8 years earlier) for respondents who were 40 years old in 2001 or 2002 and from the 1994 interview for respondents who were 40 years old in 2003 or 2004 (10 years earlier); it was available for a total of 6,229 respondents.

Because the NLSY survey was administered every other year after the 1994 interview, information on recent annual wages was available in alternating years. Annual personal income from salary and tips for the years 1993, 1995, 1997, and 1999 was used to calculate income volatility for the group turning 40 in 1999–2000; personal income in years 1995, 1997, 1999, and 2001 was used for the group turning 40 in 2000–2002; and personal income in years 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001, and 2003 was used for the group turning 40 in 2003–2004. Three or more consecutive income reports during the four- or five-year interview period were required in order to calculate the income volatility measures. Of the 6,229 respondents with both baseline and outcome CESD scores, income data for the volatility measures were available for 4,503 respondents. Of the 1,726 respondents missing on income volatility, the majority was excluded because they were not interviewed (n = 370) or reported being out of the labor force (OLF), (n = 638) for two or more years. Another 413 were excluded because they failed to report their income in two or more years, and 305 were excluded because they worked 3 years but only two were consecutive years. Of the 4,503 respondents with income and depression measures, complete data on other important study variables were available for 4,493.

Income Volatility Measures

Two measures of income volatility were calculated for individuals who reported income at three or more consecutive interviews. For the first income volatility measure, annual personal income (in dollars) was deflated using the GNP personal consumption expenditure deflator using 1993 as the base year (US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis 2004) and log10 transformed.

The measure of absolute income volatility focuses on the transitory component of earnings following the customary practice of prior econometric and policy analyses of volatility (e.g., Gottschalk 1994). The variance of logged annual earnings was calculated, within a time period, as the sum of the squared deviations of each person’s logged income from their mean annual logged income as follows:

where Absolute Volatility = Absolute Income Volatility for person i.

-

t1–t4 = 1993, 1995, 1997, 1999; 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001 or

-

t1–t5 = 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2003.

-

y it = Log10 of Personal Income (in dollars) for person i at time t.

-

T i = Number of years personal income was present for person i over T.

-

y i = Average log transformed annual income for person i over T.

The second measure of volatility, calculated over the same time period as the absolute volatility measure, represents downward volatility in income between adjacent interviews. This measure is based on the frequency of income loss. For each individual, the downward volatility measure was defined by the number of negative income changes expressed as a percent of the total number of income differences over the time period. A negative income change was defined as a 5% or greater fall in actual income (not deflated or log transformed) between adjacent interviews (i.e., the difference in income between time t and t–1 was divided by income at time t–1 to create the percentage change in income between adjacent years). The decision to use a 5% or greater fall in income to define a negative income change was arrived at after considering both a less conservative and more conservative definition of negative change. The less conservative strategy defined negative change as a one dollar or greater fall in income between adjacent interviews, whereas the more conservative strategy used a 10% or greater fall in income. All analyses were replicated using both definitions of negative change, and effect sizes for the relationship between the downward volatility measures and CESD were both statistically significant and of approximately the same magnitude. As a compromise between the less and more conservative approaches, we elected to use a 5% or greater fall in income to define a negative income change.

There was a positive correlation between the absolute volatility and downward volatility measures (r = .24, p < .001). Descriptive statistics for the income volatility measures and other study variables are presented in Table 1.

Depression Measures

CES-Depression measured in 1992 served as a baseline control for respondents who were 40 years old in 1999 or 2000 and CESD measured in 1994 served as a baseline control for respondents who turned 40 in 2001 through 2004. In 1992 the NLSY administered the complete 20-item CESD, but in 1994 an abbreviated 7-item version was used. The items, based on past week recall, were scaled 0–3 with 0 representing “rarely/none of the time/1 day” and 3 indicating “most of the time/all of the time/5–7 days”. The seven items included in the 1994 survey were: poor appetite, trouble keeping mind on tasks, depressed, took extra effort, restless sleep, sad, and could not get going. For comparability, these same seven items from the full CESD in 1992 were used to calculate baseline depression. There was high correlation between the full 20-item scale and the abbreviated 7-item scale in 1992, r = .90, p < .001. Coefficient alpha for the 7-item scale in 1992 and 1994 was .77 and .79, both p < .01.

The CESD scale was designed for general community surveys and epidemiologic studies rather than clinical diagnoses of depression. However, several studies have shown agreement between elevated CESD scores and clinical psychiatric diagnoses (Weissman et al. 1977). Further, elevated scores on the CESD are conventionally defined using a value greater than or equal to 16 on the 0–60 scale. The cut-point approach has been shown to detect elevated depressive symptoms in approximately 15% of the general population (Myer 1980; Roberts 1983; Weissman et al. 1977). Because the present study utilizes a 0–21 scale (i.e., 7-item CESD), a cut-point of greater than “6” was used to identify the top 15% of the sample in the analysis using the CESD as a dichotomous outcome. Other researchers have used different cutoffs to identify individuals with severe depressive symptoms (e.g., top 20% used in Frech 2007) and to detect “probable cases of clinical depression” (Frech 2007, p. 153).

CES-Depression measured in 2000, 2002, or 2004 was used as the outcome variable. In 2000 the NLSY administered the same 7-item version of the scale as in 1994. In 2002 and 2004, two items were added: could not shake the blues and felt lonely. However, these two items were excluded from this analysis to maintain comparability with the seven items from the 2000 interview. Coefficient alphas for the 7-item CESD in 2000, 2002, and 2004 were .84, .82, and .82, respectively, each p < .01.

Test–retest reliabilities for CESD in the baseline and outcome year were also evaluated and were .26, .37, and .30 for 2000, 2002, and 2004, respectively. Interactions between baseline CESD and other study variables were evaluated to determine whether the stability of the depression measure depended on these variables. Although small in magnitude, there was a statistically significant interaction between baseline CESD and income suggesting that the stability of the depression measure was somewhat higher in the middle and high income groups relative to the low income group (b = .061, p < .003).

Background Variables

Demographic variables, including gender, ethnicity, marital status, presence of children, years of education, and results from the armed forces qualification test (AFQT) were included in the analysis to help explain variation in the CESD outcome. Ethnicity was represented in the analysis by indicator variables for Hispanics and African Americans using the non-Hispanic/non-African American group as the reference group. Years of education, presence (or absence) of children in the household, and marital status were measured at the end of the observation period (2000, 2002, or 2004) when the CESD outcome variable was measured. Marital status was represented by indicator variables for never married and divorced/widowed/separated using married as the reference group. The AFQT, administered to the NLSY sample in 1980 and revised in 1989, served as a proxy for aptitude of the respondent and was available for 4,352 of the 4,493 respondents. These and the following variables are described in Table 1.

Four variables characterizing the extent of participation in the labor force were included as possible confounders of the relationship between income volatility and depression. These continuous variables, calculated over the same period as the income volatility measures, include the number of weeks unemployed, the number of hours worked, the number of weeks OLF, and the number of jobs held. The NLSY defines unemployment as not working or on layoff and having looked for work during the past 4 weeks. OLF is defined as not working and not actively looking for work (e.g., going to school, not able to work) (Center for Human Resource Research 2002).

The log10 transformed, deflated individual annual income (using 1993 as the base year) was used to calculate the mean income for each respondent over the time period in which the volatility measures were calculated. The NLSY uses a “top coding” method where unusually high values of income are replaced to maintain confidentiality of the respondent (Center for Human Resource Research 2002). For 1993–1995, annual income values above $100,000 were replaced with the mean of the outlying values, and beginning in 1996, annual incomes in the top 2% were replaced with the mean of the income values in the top 2%. The NLSY records zero annual income for individuals who were OLF or unemployed for 52 weeks in a given year. We elected to make annual income missing for years in which an individual was OLF for the entire year and to include a zero value for income in years that an individual was unemployed for the entire year.

Another income variable was created to represent the contribution of the respondents’ individual income to the total family income during the time period in which the volatility measures were calculated. It was computed by dividing the respondents’ total income by the total family income and serves as a proxy for principal wage earner.

Two variables were created to reflect receipt of income in the form of government assistance during the period in which the volatility measures were calculated. One measures receipt of income from TANF/AFDC, food stamps, or SSI, and another variable measures receipt of income from unemployment compensation. Because a small number of respondents reported ever receiving income from government assistance or unemployment compensation (11.4 and 18.7%, respectively), these variables are expressed as dichotomous variables indicating whether the respondent had ever received any form of government assistance or had ever received any income from unemployment compensation. These variables are included to help explain variation in CESD and to control for possible confounding of the relationship between the income volatility measures and CESD.

Variables characterizing assets were created to evaluate whether the association between the income volatility measures and depression might depend on the amount of savings or home ownership. Average savings were calculated by averaging the respondents’ report of their savings (in dollars) at each interview during the time period in which the volatility measures were calculated. This variable was originally represented as quartiles of savings where individuals who reported having no savings are included in the lowest quartile of savings and an additional category was coded to represent individuals who failed to report savings data. Initially, analyses conducted using a series of indicator variables representing these groups with the 4th quartile of savings serving as the reference group, demonstrated no significant difference in depression between the second and third quartiles relative to the fourth, so we elected to more parsimoniously represent savings using two indicator variables, one for no savings or first quartile of savings (low savings) and another for missing information on savings. Home ownership was coded dichotomously to represent whether the respondent had ever owned a home during the measurement period.

The source year of the outcome measure from the NLSY 40+ Health Module was characterized using two indicator variables, one representing 2002 and another representing 2004 with source year 2000 serving as the reference group. Although there was an 8 year lag between the measurement of baseline CESD and outcome CESD for source years 2000 and 2002, there was a 10 year lag for 2004. Because of the differential lags, the two indicator variables were included in all regression models and their interactions with both baseline depression and the two measures of income volatility were tested. Although there were no statistically significant interactions between source year and the income volatility measures, there was a significant interaction between source year 2002 and baseline depression (b = .084, p < .05) suggesting a somewhat stronger association between baseline and outcome CESD in source year 2002 when compared to 2000. Importantly, in source year 2004 where there was a 10 year lag between baseline and outcome CESD as opposed to an 8 year lag, the stability of the depression measure did not differ from 2000.

Attrition Analysis

Of the respondents with outcome CESD scores (n = 6,229), those who were included in the analyses (n = 4,493) were compared to respondents who were excluded for missing data (n = 1,736). Excluded respondents had less education (M = 12.5 years, SD = 2.5 vs. M = 13.4 years, SD = 2.4, p < .001) and lower aptitude as measured by the AFQT (M = 29.5, SD = 26.7 vs. M = 42.3, SD = 28.4, p < .001), and were slightly older (M = 31.8 years, SD = 1.7 vs. M = 31.4 years, SD = 1.7, p < .001). Additionally, the excluded group had proportionally fewer males (41.3 vs. 51.9%, p < .001), more African Americans (37.2 vs. 28.0%, p < .001), fewer married (54.4 vs. 63.7%, p < .001), and fewer with children in the home (62.2 vs. 67.6%, p < .001) compared to the sample included in the analyses. Although these comparisons were statistically significant, the effect sizes were small, as measured by Cramer’s Phi2 for the categorical variables (.003 for presence of children in the home to .013 for ethnicity) and were small to medium using the point biserial correlation2 \( \left( {r_{\text{pb}}^{2} } \right) \) for the continuous variables (.013 for age to .039 for AFQT score) (Witte 2004). Excluded respondents had higher depression at both baseline 1992/1994 (M = 4.7, SD = 4.6 vs. M = 3.6, SD = 3.7, p < .001) and at the outcome year (M = 4.4, SD = 5.0 vs. M = 3.0, SD = 3.8, p < .001) with effect sizes in the small range (\( r_{\text{pb}}^{2} \) = .017 and .021, respectively).

Statistical Analysis

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used to describe the association between the measures of income volatility and depression, adjusting for the study covariates. All regression models include baseline depression as a control for reverse causation and two indicator variables representing the year the outcome was measured with 2000 serving as the reference group. Main effects for absolute volatility and downward volatility tested hypotheses one and two, and product term interactions between absolute income volatility and downward volatility were evaluated to test hypothesis three.

Additionally, interactions between the background variables, baseline depression and both of the volatility measures were evaluated to determine whether the association between the two volatility measures and depression might depend on background factors such as gender or income. Continuous variables (e.g., baseline depression, percentage of negative income change, mean logged income) are represented in centered form in the regression models to reduce nonessential multicollinearity among main effects and product terms (Cohen et al. 2006). Main effects and interaction terms reaching the p = .05 level of significance are included in the models. Residuals from the regression models were screened for violations of OLS assumptions and were deemed acceptable for inferential purposes.

Results

Bivariate Associations

The bivariate relationship between CESD and absolute volatility was curvilinear and best represented using a second degree polynomial function. Both the linear (b = .809, p < .005) and quadratic (b = −.256, p < .005) terms were significant (multiple R = .081, p < .001) suggesting very little change in depression along the lowest range of absolute volatility then increasing depression along the middle and upper range of volatility.

Because of the non-linear pattern of association between absolute volatility and CESD we elected to categorize absolute volatility into quartiles in order to highlight the effects of low and high absolute volatility on depression. Absolute volatility was significantly associated with depression (F = 9.6(3,4171), p < .001, ω 2 = .007). Depression was significantly higher in the 4th quartile when compared to both the first and second quartiles. However, after adjusting for baseline depression, the bivariate association was no longer significant.

Downward volatility had a small, positive association with depression (r 2 = .008, p < .001). Adjusting for baseline depression, the association was larger (r 2 = .102, p < .001) indicating that a higher percentage of negative income change was associated with higher depression.

Multivariable Models

Table 2 presents the results of a series of OLS regressions describing the association between the volatility measures and depression. Adjusting for baseline depression, mean income, and other study variables, there was no association between depression and absolute income volatility contrary to hypothesis 1 (Model 1). The percentage of negative income change was positively associated with depression when adjusting for absolute volatility and other control variables consistent with hypothesis 2 (Model 2, b = .008, p < .002). With the downward volatility measure included in the model, depression was significantly lower when absolute volatility was higher (b = −.340, p < .05 for the second quartile and b = −.521, p < .02, for the 4th quartile, both relative to first quartile).

When controlling for the extent of participation in the labor force, savings, and receipt of government assistance, absolute volatility and downward volatility remained significantly associated with depression (Model 3). The number of weeks unemployed, number of weeks OLF, receipt of government assistance or unemployment compensation, and low savings were each positively associated with depression.

Some of the background variables were not significant predictors of CESD in the regression models and were not significant when tested as moderators of the relationship between the income volatility measures and depression. For the sake of parsimony these variables were omitted from the regression models (e.g., AFQT, presence of children, ratio of personal to family income, number of jobs held.) An indicator variable reflecting whether income decreased by more than 5% in the final pair of years right before measurement of the depression outcome was also tested. This indicator variable was not significantly associated with depression when controlling for the two measures of income volatility.

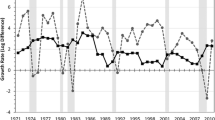

Product term interactions between downward volatility and the three indicator variables representing absolute volatility were evaluated to test hypothesis 3 (Table 2, Model 4). The term involving the 4th quartile of absolute volatility (relative to the first) was statistically significant (b = .014, p < .05) indicating that when absolute volatility was high, the relationship between depression and downward volatility was positive; depression was lowest when the percentage of negative income change was low and depression was highest when the percentage of negative income change was high (see Fig. 1). In contrast, downward volatility in income was not associated with depression when absolute volatility was low (e.g., in the lowest quartile of absolute volatility).

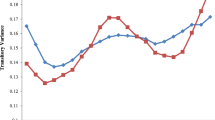

After testing a series of plausible moderators, the one statistically significant interaction with the downward volatility measure of income volatility involved mean income (Table 2, Model 5: b = −.009, p < .009). The direction of this interaction suggested a strong positive association between percentage of negative income change and depression in the low income group; whereas in the high income group, there was no association (see Fig. 2). Interactions with baseline depression and all study variables were examined and two significant interactions were detected. The first was between baseline depression and source year (2002) and the second was between baseline depression and mean income. These interactions were previously discussed in the Methods section.

To help clarify the clinical significance of the findings, the analyses were replicated using two different operationalizations of CESD. The first strategy dichotomized CESD to identify the top 15% of the sample (a cutpoint value greater than “6” on the 7-item, composite CESD). A multivariable logistic regression, using the same series of five models presented in Table 2, replicated all of the income volatility associations with depression with the exception of the interaction between the 4th quartile of absolute volatility and downward volatility. Importantly, the coefficient for the interaction term in the logistic regression, although not statistically significant, was of the same direction and interpretation as in the OLS findings. One plausible reason for failure to statistically detect the interaction in the logistic regression is the relative power differential between the two techniques. In logistic regression, power is maximized when the “event” rate is .50. In our analysis, the proportion with high depressive symptoms is necessarily less (i.e., .15) and we believe that power to detect the interaction was somewhat less in the logistic regression.

The second strategy operationalized depression as a count of the number of CESD symptoms reported in the past 7 days (ranging from 0 to 7) and utilized a Poisson regression to replicate the series of models presented in Table 2. The findings from the Poisson regression replicated all of the findings from the OLS analyses including associations between the two volatility measures and CESD as well as all of the interactions. Based on the results of these supplementary analyses, it appears that income volatility also predicts serious levels of depression as well as symptoms of depression.

Discussion

Summary

Absolute and downward volatility correlated modestly with each other, and although downward volatility was significantly associated with depression when controlling for baseline depression, absolute volatility was not. However, when absolute volatility was adjusted for downward volatility and other study variables, high absolute volatility was associated with lower depression and high downward volatility was associated with higher depression. The interaction between the two volatility measures supported the prediction that downward volatility in income would predict depression when absolute volatility was high and have a weaker association with depression when absolute volatility was low. High income appeared to buffer the effects of downward volatility on depression whereas those with lower incomes were more vulnerable to the adverse effects of downward volatility.

The first hypothesis, that absolute volatility would predict later depression, was not supported. The initial positive association between absolute volatility and later depression disappeared upon entry of baseline depression and other control variables. However, downward volatility appeared to operate as a suppressor of the relationship between absolute volatility and depression, when adjusting for baseline depression and other study variables. When absolute volatility was adjusted for downward volatility, it was negatively associated with depression, i.e., higher volatility was associated with lower depression, and this finding persisted with inclusion of all control variables. Although this suppressor relationship was not anticipated, it may reflect the beneficial effects of desirable income volatility, i.e., the income increases after adjusting for income drops measured by the downward volatility variable.

The second hypothesis, that downward volatility would predict depression, received support. The frequency of income loss was significantly associated with depression even after controlling for baseline depression, respondent characteristics, mean income, savings and assets, and employment characteristics such as weeks unemployed and weeks OLF. To give a sense of the size of this effect, compare three predictors: downward volatility, ever receiving unemployment compensation and years of education. The adverse effect of directional income change on depression (β = .04) was on par with ever having received unemployment compensation and years of education (β = .03 and −.04, respectively). Importantly, income appeared to buffer the adverse effects of downward volatility, which agrees with prior findings that adverse income change is more harmful for those with already low incomes (Dearing et al. 2001; Votruba-Drzal 2003). Thus, people of low-income level are both more at risk of experiencing income loss and more vulnerable psychologically when such losses occur. In contrast to income, baseline depression did not moderate the association between the income volatility measures and depression, suggesting that higher levels of prior depression did not leave people more vulnerable to the adverse effects of income volatility.

The main effects of these two measures are better understood in the context of their interaction. There was support for the third hypothesis, that absolute volatility would moderate the association between downward volatility (income loss) and depression. There was no association between downward volatility (income loss) and depression when absolute volatility was low; in contrast, when absolute volatility was high, there was a strong positive association between income loss and depression. This pattern suggests a dose response relationship between the magnitude of income loss and depression. The downward volatility measure reflects the frequency of income drops that can range from small to large. The absolute volatility measure reflects the magnitude of change that can range from positive to negative. The interaction indicates that large income losses have more impact on depression than do small losses.

In sum, these findings support the view that downward income change rather than change per se affects depression. This result agrees with the life events literature that generally finds adverse life events more hazardous for well-being than total life events or favorable events (Vinokur 1975).

Limitations

Although the data set provided several potential moderators (e.g., safety net variables such as house ownership, assets, unemployment compensation, and welfare payments), it did not allow testing of some likely mediators of the effect of the volatility measures on depression. For example, decreased income would likely lead to material changes in life style resulting in financial strains that have been linked to adverse psychological outcomes (Kessler 1988; Price et al. 2002). Other potential mediators include adverse changes in health insurance coverage, decreased contributions to pension plans, tiring or frustrating efforts to find other sources of income, and emotional disruption of family ties. One likely psycho-social mediator is that of perceived control, which has been found to mediate the effects of low income on life satisfaction (Johnson 2006). Future studies might try to capture such unfolding consequences of income volatility.

The data set offered a restricted age range consisting mainly of workers in their early to middle career years. This would seem to be a critical section of the labor force, but it may differ in vulnerability to economic shocks compared with younger people with less seniority and older workers with less ability to adapt. Thus it will be important to check the interaction with age in more diverse samples.

The data set also did not provide longitudinal measures of depression after 1994, hence the depression outcome was measured at a single point in time (when the respondent turned 40 or 41 years old). Although depression is often situational and connected to more recent events, we were only able to test the association of downward income change directly before measurement of the depression outcome at a single point in time. Analyses of the research hypotheses could have been more refined had the data set provided additional longitudinal assessments of depression that coincided with annual income.

One limitation inherent in studying income volatility is that, compared with cross-sectional indicators, subjects who are missing income data at some interviews must be excluded. In the present study, such attrition appeared to be biased towards the exclusion of those with more volatility and fewer resources for coping. If these missing respondents felt greater impacts of volatility, the present findings would, by virtue of their range restriction, give a conservative estimate of the adverse effect of signed change. The inclusion of respondents with more extreme volatility might have revealed significant impacts for absolute volatility or greater effects for downward volatility. But it is also conceivable that respondents experiencing more volatility are more accustomed to it and so less likely to respond adversely.

Perhaps contributing to the problem of range restriction, the time period of this study (the 1990s) saw generally robust economic growth and declining unemployment (see Dooley 2004). To the extent that this time frame does not represent typical economic downturns, it would not yield a generalizable estimate of the effect of income volatility. Only replication over various stages of the business cycle can clarify this issue.

On the other hand this study did offer several improvements on prior studies of income volatility. First, it extended the prior research that had documented the increase in volatility (Gottschalk 1994) by testing the assumption that volatility was harmful for psychological well-being. Moreover it did so using longitudinal data to control for possible reverse causation as well as other potential confounders. Secondly, it enlarged the usual focus of such research on white men (Gottschalk 1994) to include women and minorities and so was able to check the potential moderation of any volatility effects by such variables as gender and ethnicity (finding none). Finally, it went beyond prior econometric studies of volatility to consider downward as well as absolute volatility.

Implications

This study shows how income volatility, in addition to the more frequently studied employment variables such as job loss, can be brought into the domain of social epidemiology. Moreover, it provides evidence that downward not absolute change is more important in predicting depression. These findings invite research to explain how negative income change has an impact net of other economic stressors such as unemployment episodes and average income level. But even when focused on these other variables, research might usefully include volatility as a potential control or moderator as it may add explanation over and above baseline income and employment status.

These results should also hold interest for policy makers because the observed effects appear to reach social as well as statistical significance. Although the present study did not include a clinical diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, there is ample basis for viewing the present symptom measure as tapping a continuum ranging up to severe depression (Flett 1997). With respect to impact, this study finds that the magnitude of the downward income change effect is greater than or comparable to that of income level, consistent with earlier research (Elder et al. 1992).

Policy makers dealing with health and well-being should add recent income volatility to the other socio-economic variables that are already recognized as risk factors. If the social contract for workers is changing such that growing numbers will be working without assurance of steady employment at fixed hours and wages, then income volatility may play an increasing role compared to traditional dichotomous status measures such as employment/unemployment. Although some existing safety net programs such as unemployment insurance are designed to reduce income volatility, the insured share of the work force has been declining while income volatility has been rising. If reducing the social cost of adverse income change becomes a serious goal, then new or improved policies will be required.

The present findings link negative income shocks to one health problem, but income volatility is just one aspect of rising economic risk including insecurity in employment, health care, and retirement (Hacker 2006). Ideally the threat of increased economic risk would be met by primary preventive policies in place before the experience of income loss. Two variants of primary prevention appear relevant to employment related risk factors (Dooley 2000). Proactive interventions attempt to prevent exposure to the hazard, and reactive ones operate after exposure with the aim of inoculation against its worst effects.

Legislating government policies that could proactively prevent income oscillations throughout the population appears politically unlikely. By default, individuals must assume responsibility for managing their own risk exposure. Educational programs aimed at increasing awareness of the importance of savings as a cushion against rising economic risks may be beneficial to those with enough resources to allow saving, but may be unrealistic for people most vulnerable to downward income shocks—the lower income workers who do not have margins for saving. The inability of some groups to self-insure through savings is precisely why support should be mustered for government policies that encourage individual-level risk-prevention actions with tax incentives for career retraining, purchasing health insurance, and investing in retirement programs.

But reactive primary prevention will still be needed because uncontrollable events such as plant closures, outsourcing of jobs, or disabling health problems will continue to strike even the most responsible workers from time to time. The best response for these kinds of hazards is pooled risk insurance in which the government provides the safety net of last resort. One such safety net is unemployment insurance, but it is inadequate for three reasons (Dooley 2004; Hacker 2006). First, most American workers are not covered by unemployment insurance, and the number of uninsured has been steadily rising. Second, coverage usually only lasts for 6 months leaving the long-term unemployed without support. Third, such insurance only provides protection following complete job loss, but income drops can affect still employed workers, e.g., forced pay cuts or part-time work, loss of a second or third job, missed work due to illness without sick leave coverage.

As an improvement on unemployment insurance, Hacker (2006) has argued for “wage insurance”. But because economic risks involve more than just income drops, Hacker goes further to suggest a more comprehensive approach that he calls “universal insurance”. This program would fill the gaps left by all current public safety net programs and do so progressively in that it would be more generous for people of lower average income who experience greater losses. Political support for such economic security programs remains to be generated. However, social researchers might contribute to this political process through social cost accounting such as that offered in this study.

References

Benzeval, M., & Judge, K. (2001). Income and health: The time dimension. Social Science and Medicine, 52, 1371–1390.

Brown, G., & Harris, T. (1978). Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York: Free Press.

Catalano, R., & Dooley, D. (1977). Economic predictors of depressed mood and stressful life events in a metropolitan community. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 18, 292–307.

Center for Human Resource Research. (2002). NLSY79 user’s guide: A guide to the 1979–2002 national longitudinal survey of youth data. Columbus, OH: The Ohio State University.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2006). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dearing, E., McCartney, K., & Taylor, B. A. (2001). Change in family income-to-needs matters more for children with less. Child Development, 72, 1779–1793.

De Witte, H. (1999). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8, 155–177.

Dooley, D., & Catalano, R. (2000). Group interventions and the limits of behavioral medicine. Behavioral Medicine, 26, 116–128.

Dooley, D., & Prause, J. (2002). Mental health and welfare transitions: Depression and alcohol abuse in AFDC women. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 787–813.

Dooley, D., & Prause, J. (2004). The social costs of underemployment. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dooley, D., Prause, J., & Ham-Rowbottom, K. (2000). Unemployment and depression: Longitudinal relationships. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 421–436.

Dooley, D., Rook, K., & Catalano, R. (1987). Job and non-job stressors and their moderators. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 60, 115–132.

Durkheim, E. (1966). Suicide: A study in sociology. J. Spaulding & G. Simpson, translators. New York: Free Press. (Originally published in 1897).

Elder, G. H., Jr., Conger, R. D., Foster, E. M., & Ardelt, M. (1992). Families under economic pressure. Journal of Family Issues, 13, 5–37.

Evenson, R., & Simon, R. (2005). Clarifying the relationship between parenthood and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 341–358.

Flett, G. L., Vredenburg, K., & Krames, L. (1997). The continuity of depression in clinical and nonclinical samples. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 395–416.

Frech, A., & Williams, K. (2007). Depression and the psychological benefits of entering marriage. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48, 149–163.

Gottschalk, P., & Moffitt, R. (1994). The growth of earnings instability in the US labor market. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 217–272.

Greenberg, P., Kessler, R., Birnbaum, H., Leong, S., Lowe, S., Berglund, P., et al. (2003). The economic burden of depression in the United States: How did it change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 1465–1475.

Hacker, J. S. (2004). Privatizing risk without privatizing the welfare state: The hidden politics of social policy retrenchment in the United States. American Political Science Review, 98, 243–260.

Hacker, J. S. (2006). The great risk shift: The assault on American jobs, families, health care, and retirement and how you can fight back. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hill, T., Ross, C., & Angel, R. (2005). Neighborhood disorder, psychophysiological distress, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 170–186.

Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. E. (1967). The social readjustment scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

Johnson, W., & Krueger, R. F. (2006). How money buys happiness: Genetic and environmental processes linking finances and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 680–691.

Kessler, R. C. (1997). The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 191–214.

Kessler, R. C., Turner, J. B., & House, J. S. (1988). Effects of unemployment on health in a community survey: Main, modifying, and mediating effects. Journal of Social Issues, 44(4), 69–85.

Martikainen, P., Adda, J., Ferrie, J. E., Smith, G., Davey, & Marmot, M. (2003). Effects of income and wealth on GHQ depression and poor self rated health in white collar women and men in the Whitehall II study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 718–723.

Mistry, R. S., Biesanz, J. C., Taylor, L. C., Burchinal, M., & Cox, M. J. (2004). Family income and its relation to preschool children’s adjustment for families in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. Developmental Psychology, 40, 727–745.

Montgomery, S., Cook, D., Bartley, M., & Wadsworth, M. (1999). Unemployment pre-dates symptoms of depression and anxiety resulting in medical consultation in young men. International Journal of Epidemiology, 28, 95–100.

Moffitt, R., & Gottschalk, P. (2002). Trends in the transitory variance of earnings in the United States. Economic Journal, 112 (March), C68–C73.

Myer, J. K., & Weissman, M. M. (1980). Use of a self-report symptoms scale to detect depression in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 137, 1081–1084.

Pierce, A. (1967). The economic cycle and the social suicide rate. American Sociological Review, 32, 457–462.

Price, R. H., Choi, J. N., & Vinokur, A. D. (2002). Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: How financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 302–312.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Roberts, R. E., & Vernon, S. W. (1983). The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: Its use in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 41–46.

Schmidt, S. R. (1999). Long-run trends in workers’ beliefs about their own job security: Evidence from the general social survey. Journal of Labor Economics, 17((4, pt 2)), S127–S141.

Sobocki, P., Jonsson, B., Angst, J., & Rehnberg, C. (2006). Cost of depression in Europe. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 9, 87–98.

Stevens, A. H. (2001). Changes in earnings instability and job loss. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55, 60–78.

Sverke, M., & Hellgren, J. (2002). The nature of job insecurity: Understanding employment uncertainty on the brink of a new millennium. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 23–42.

Thomas, C., & Morris, S. (2003). Cost of depression among adults in England in 2000. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 514–519.

US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2004). National economic accounts. Retrieved 23 November 2004, from http://www.bea.doc.gov/bea/dn/nipaweb/Tableview.asp#Mid.

Vinokur, A., & Selzer, M. L. (1975). Desirable vs. undesirable life events: Their relationship to stress and mental distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 329–337.

Votruba-Drzal, E. (2003). Income changes and cognitive stimulation in young children’s home learning environments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 341–355.

Witte, R., & Witte, J. (2004). Statistics (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Weissman, M. M., Sholomskas, D., Pottenger, M., & Prusoff, B. A. (1977). Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 106(3), 203–214.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prause, J., Dooley, D. & Huh, J. Income Volatility and Psychological Depression. Am J Community Psychol 43, 57–70 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9219-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9219-3