Abstract

Intersectional stigma and discrimination have increasingly been recognized as impediments to the health and well-being of young Black sexual minority men (YBSMM) and transgender women (TW). However, little research has examined the relationship between intersectional discrimination and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) outcomes. This study with 283 YBSMM and TW examines the relationship between intersectional discrimination and current PrEP use and likelihood of future PrEP use. Path models were used to test associations between intersectional discrimination, resilience and social support, and PrEP use and intentions. Individuals with higher levels of anticipated discrimination were less likely to be current PrEP users (OR = 0.59, p = .013), and higher levels of daily discrimination were associated with increased likelihood of using PrEP in the future (B = 0.48 (0.16), p = .002). Greater discrimination was associated with higher levels of resilience, social support, and connection to the Black LGBTQ community. Social support mediated the effect of day-to-day discrimination on likelihood of future PrEP use. Additionally, there was a significant and negative indirect effect of PrEP social concerns on current PrEP use via Black LGBTQ community connectedness. The results of this study highlight the complexity of the relationships between discrimination, resilience, and health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Black gay, bisexual, and other sexual minority men (SMM) in the United States (US) continue to experience a disproportionate burden of HIV [1]. In 2017, the rate of new HIV diagnoses among Black adults and adolescents was eight times that of white and more than twice that of Latinx individuals [2]. In 2018, SMM made up 92% of new HIV cases among adolescents and young adults aged 13 to 24, of whom 51% were among young Black SMM (YBSMM) [3]. Black transgender women (TW) also face significant disparities in HIV; among all trans women, HIV prevalence is 44.2% among Black TW, compared to 6.7% among white TW [4].

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a key aspect of HIV prevention. In areas of high PrEP uptake, HIV incidence is significantly reduced, even when controlling for viral suppression [5]. Yet, PrEP has been slow to reach communities in the US that experience a disproportionate burden of HIV [6,7,8,9]. While evidence indicates that PrEP use may be increasing, [10] persistent racial disparities remain. Although PrEP awareness among Black TW is high, PrEP initiation and consistent use remain low [11, 12]. Between 2014 and 2016, Black individuals accounted for approximately 44% of those indicated for PrEP, yet just 11% of PrEP users during that same time period were Black [10]. Current estimates indicate that about 10% of PrEP users are Black SMM [13,14,15]. Furthermore, data indicate that only between 12 and 20% of Black SMM on PrEP achieve protective levels of PrEP [16,17,18].

Prior research has examined myriad individual, social, and structural factors, and their association with disparities in PrEP uptake [19]. One factor thought to contribute to the slow and uneven rollout of PrEP among Black SMM and TW communities is stigma and discrimination. There is evidence, for example, that unconscious bias among medical providers may lead to reduced willingness to prescribe PrEP to Black patients [20]. Additionally, experienced and anticipated racism and homonegativity in healthcare settings may contribute to difficulty receiving PrEP prescriptions among YBSMM [21] and TW [22]. Although sexuality disclosure to healthcare providers is positively associated with HIV prevention services among YBSMM, [23] individuals may be hesitant to disclose their sexuality if they worry about mistreatment from providers. There is also evidence that structural-level stigma may contribute to PrEP disparities. In states with nondiscrimination laws that protect sexual and gender minorities, there are higher levels of PrEP awareness and uptake [24]. Similarly, SMM who reside in states with high LGBTQ equity (as measured by state-level laws and policies affecting LGBTQ individuals), have significantly higher odds of PrEP use, compared to low equality states [25].

Influenced by intersectionality scholarship, research on the effects of stigma and discrimination on HIV disparities has largely shifted from examining a singular type of stigma toward examining the interlocking nature of various forms of stigma, oppression, and discrimination. Intersectionality is rooted in Black feminist thought [26,27,28] and highlights the ways that various forms of oppression (e.g. racism, heterosexism, sexism) are mutually reinforcing and should be considered simultaneously.[29, 30] Intersectionality scholarship suggests that marginalized social identities intersect and reflect multiple systems of societal oppression and power. [26, 30] Intersectional discrimination [31] is the process by which some individuals are exposed to multiple forms of oppression, prejudice, and discrimination.

There is some evidence that intersectional stigma and discrimination influence health outcomes among Black SMM and TW, [32, 33] although little research has examined the relationship between intersectional discrimination and PrEP use. In research with Black SMM living with HIV, Bogart and colleagues found that discrimination based on race, sexual orientation, and HIV interacted to predict higher levels of depressive symptoms, although none of the main effects from these forms of discrimination were individually associated with depressive symptoms. [34] More recent research has examined the interaction between racial discrimination and gay rejection sensitivity and found that the interaction of these constructs contributed to higher levels of emotion regulation difficulties, and subsequently, to heavy drinking among Black, Latinx, and multiracial SMM. [35] Intersectional stigma can also contribute to negative self-concept, negative future orientation, and reduced sense of social connectedness, which can place individuals at greater vulnerability to HIV [36, 37] and limit engagement in HIV prevention interventions, including PrEP. Qualitative research has begun to investigate how experiences of stigma and discrimination may influence PrEP use. [38, 39] For example, the intersections of racism and homonegativity can negatively affect YBSMM’s interactions with the healthcare system and contribute to medical mistrust, disengagement from the healthcare system, and skepticism surrounding PrEP [21].

Increasingly, resilience has been incorporated into intersectional stigma research to understand how various resilience resources may help racial minority SMM and TW cope with and respond to stigma and discrimination [40,41,42]. Resilience is a dynamic process wherein individuals are able to positively adapt or succeed within the context of adversity. [43, 44] Positive adaptation occurs via protective internal assets (individual-level resilience) or external resources (supportive social environments) that can help facilitate positive health outcomes,[45] such as social support [46,47,48] and connection to an affirming LGBTQ community.[49, 50] Individuals who face stigma and discrimination may seek out supportive social environments that offer a sense of safety and protection and build community in response to discrimination.

The psychological mediation framework posits that stigma-related stressors render sexual and gender minorities vulnerable to psychological processes that predict mental health outcomes. [51] Stigma and discrimination-related stressors can shape individual coping processes, including the development of resilience, building of social support, and stronger ties to the LGBTQ community, which in turn may mediate the process between stigma or discrimination and PrEP use outcomes. Research has demonstrated support for this model in examining resilient coping and social support as mediators of the relationship between sexual minority stigma and depression. [52,53,54] Prior research with gay men has also shown that, in response to discrimination, men developed resilience and built supportive social networks to overcome daily adversity. [55] This aligns with stress inoculation theories, which suggest that early experiences of racism may help racial minority LGBTQ individuals develop resilience processes. [56] YBSMM and TW who experience discrimination may receive support and learn coping skills for dealing with discrimination and may demonstrate greater resilience in the face of stigma due to stress-inoculation processes [57].

However, there is little research on the relationship between intersectional discrimination and PrEP use, and what role resilience factors may play. This is a critical gap in our understanding of how intersectional discrimination influences HIV prevention efforts and may help inform interventions to increase access to and usage of PrEP among YBSMM, TW, and others who contend with multiple societal stigmas. To that end, this study examined the relationship between intersectional discrimination and PrEP use among YBSMM and TW, and the role of resilience, social support, and Black LGBTQ community connectedness as potential mediators. Research has demonstrated that there are likely multiple mediating and moderating pathways of resilience factors. [58] The models tested in this paper are rooted in the psychological mediation framework, as we examine resilience factors that may be activated in response to the stigma experienced.[59] We hypothesized that individuals who have experienced higher levels of intersectional discrimination (that is, discrimination based on their marginalized intersectional identities) would be less likely to currently use PrEP and less likely to use PrEP in the future than those who have experienced less discrimination. However, given evidence that discrimination may also contribute to resilience, we also hypothesized that resilience factors would mediate associations between intersectional stigma and PrEP use. Specifically, we predicted that intersectional discrimination would be positively associated with resilience, social support, and Black LGBTQ community support, which in turn would be positively associated with PrEP use.

Methods

Between 2018 and 2020, we recruited 283 YBSMM to participate in this study. Eligibility criteria included: (1) self-identifying as Black or African American, (2) assigned male sex at birth, (3) being between the ages of 16 and 25, (4) identifying as gay, bisexual, or other sexual minority status, (5) residing in Milwaukee, WI or Cleveland, OH, and (6) reporting a negative or unknown HIV status.

Cleveland and Milwaukee are two mid-size midwestern cities with significant racial disparities in HIV and low uptake of PrEP. Geographically, both Cuyahoga and Milwaukee counties in Ohio and Wisconsin, respectively, have a disproportionate share of the states’ HIV incidence.[60, 61] In both cities, young Black SMM and TW are disproportionately affected by HIV.[60, 61] In 2018, 65% of new infections among African Americans in in Ohio were among SMM.[60] Similarly, in Wisconsin in 2018, racial and ethnic minorities made up just 18% of Wisconsin’s population yet consisted of 66% of new HIV diagnoses.

Participants were recruited through outreach activities led by experienced research associates in both cities. Outreach efforts included in-person recruitment at community organizations and social venues frequented by YBSMM, social media postings, and paid advertising on the dating/hookup smartphone apps Jack’d and Grindr. Interested individuals were screened for eligibility by study staff and eligible participants scheduled a time to complete the self-administered Qualtrics assessment in person in a community-based setting. Beginning in mid-2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, enrollment shifted to allow eligible participants to be sent a personalized link to the assessment to complete at home. Given the stigmatized nature of HIV, PrEP and sexuality, we received a waiver of parental/guardian consent for participants under the age of 18 and a waiver of documented consent for all participants. Prior to accessing the survey, participants were given an informational letter outlining the study procedures and risks and benefits and providing contact information for study team members and the PI. The median survey completion time was 32 min. Participants received $50 for completing the survey, along with a list of community resources. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at [Blinded for Review].

Measures

Assessment content was informed by focus groups conducted in 2017 and 2018 with YBSMM that explored intersectional stigma, HIV prevention, and PrEP use [Blinded for Review].

Demographics and other covariates. For city, we examined whether participants were enrolled in Cleveland or Milwaukee. We coded whether participants had enrolled in the study following COVID-19 shutdowns in March 2020. Participants self-reported their age, gender identity, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and highest level of education. A dummy variable was created indicating transgender, non-binary, or another gender identity; male gender identity served as the reference category. For sexual orientation, dummy variables were created indicating bisexual sexual orientation and straight/heterosexual or another sexual orientation; gay sexual orientation served as the reference category. A dummy variable indicated Latinx ethnicity; non-Latinx ethnicity was the reference category. Education was coded as never graduated high school (0), graduated high school or GED (1), some college (2), or graduated college or graduate schooling (3). To assess economic hardship, participants responded to 3 items (α = 0.81, e.g., “In the last 12 months, how often did you run out of money for your basic necessities?” [62]) using a scale of never (0) to many times (3). Items were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater economic hardship. Participants reported whether they currently had health insurance (0 = no, 1 = yes). An item assessed the number of sexual partners in the past 30 days (0 = 0, 1 = 1, 2 = 2–3, 4 = 4 or more). Finally, participants responded to 10 items assessing psychological distress (α = 0.95, e.g., “During the last 30 days, about how often did you feel depressed?” [63]) using a scale of none of the time (1) to all of the time (5). Items were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater distress.

Current PrEP use and likelihood of future PrEP use. We considered two separate outcome variables. First, participants reported whether they were currently taking PrEP (0 = no, 1 = yes). Second, those who were not currently taking PrEP reported their likelihood of taking PrEP in the future [64] (“How likely would you be to use PrEP in the future?”), with response options being not at all likely (1), probably not likely (2), neutral (3), probably likely (4), and definitely likely (5). Those who reported that they had never heard of PrEP did not respond to questions about current or future use and were coded as not currently taking PrEP (0) and not at all likely to take it in the future (1).

Stigma-related constructs

Intersectional discrimination. The Intersectional Discrimination Index (InDI) developed by Scheim and Bauer [65] was used to measure intersectional anticipated discrimination, day-to-day discrimination, and major discrimination (lifetime). The InDI was explicitly developed to assess discrimination across a range of intersectional marginalized social identities and positions by asking participants to endorse discriminatory experiences “because of who I am,” rather than attributing an experience of discrimination to a single axis of one’s identity (e.g., discrimination due to race). Prior research has shown that attributions in discrimination measures are difficult and even impossible for some research participants to answer. [28] For anticipated discrimination, participants responded to 9 items (e.g., “Because of who I am, a doctor or nurse or other health care provider might treat me poorly”) on a scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Items were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater anticipated discrimination (α = 0.91). For day-to-day discrimination, participants indicated how frequently they had experienced 9 types of discrimination (e.g., “Been called names or heard/saw your identity used as an insult”); for each item, frequency was coded as never or not in the past year (0), once or twice in the past year (1), or many times in the past year (2). Items were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater day-to-day discrimination (α = 0.91). Finally, for major discrimination, participants indicated how frequently they had experienced 14 types of discrimination in their lifetime (e.g., “Because of who you are, has a health care provider ever refused you care?”), with response options being never (0), once (1), or more than once (2). Items were averaged (α = 0.89), with higher scores indicating more major discrimination experiences. Reliability of these three subscales was higher in this study (α = 0.89–91) than in the initial scale development study (α = 0.70–72) [65].

Interpersonal homophobia and racism. In addition to intersectional discrimination, we also measured experiences of interpersonal homophobia and racism with 9 items from Jeffries et al. (2013) that assessed the number of times in the last 12 months participants experienced a specific event, (e.g., “Felt that white gay men are uncomfortable around me because of my race or ethnicity”) using the response options never (0), once (1), and 2 + times (2). Items were averaged (α = 0.92), with higher scores indicating more experiences of interpersonal homophobia and racism [66].

Microaggressions. The 18-item LGBT People of Color Microaggressions scale [67] assessed whether individuals had ever experienced various microaggressions (e.g., “Being told that race isn’t important by white LGBT people”) and how much those experiences bothered participants. Responses were on a scale from it did not happen/is not applicable to me (0) to it happened and it bothered me EXTREMELY (5). Items were averaged (α = 0.96), with higher scores indicating more microaggressions.

PrEP social concerns. PrEP social concerns were assessed with 5 items developed for this study based on findings from our preliminary qualitative research [21] and prior measures of PrEP stigma [68, 69] (e.g., “I would be concerned if my friends found out I was taking PrEP”). Responses were on a scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Items were averaged (α = 0.90), with higher scores indicating more social concerns related to using PrEP.

Resilience-related constructs

Resilience. Resilience was assessed with 10 items from the Connor-Davidson Resilience scale, [70] (e.g., “Having to cope with stress can make me stronger”). Responses were on a scale from not at all true (0) to true nearly all the time (4). Items were averaged (α = 0.97), with higher scores indicating greater resilience.

Social support. Social support was assessed with 12 items from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Support [71] that asked about support available from family, friends, and significant others (e.g., “I can count on my friends when things go wrong”). Responses were on a scale from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (7). Items were averaged (α = 0.97), with higher scores indicating greater social support.

Black LGBT community connectedness. Black LGBT community connectedness was assessed with 8 items adapted from Frost and Meyer [72]. Items were adapted to incorporate race (e.g., “I feel I am part of my community’s Black LGBT community”). Responses were on a scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Items were averaged (α = 0.94), with higher scores indicating greater connection to the Black LGBT community.

Data Analysis

Missing data was relatively rare (3% of all data was missing). To address missing data, we used multiple imputation (MI), a modern method for dealing with missing data which allowed us to maintain the maximum sample size and avoid biases associated with complete case analysis or single imputations All study variables were included when imputing 100 datasets in Mplus 8. [73] Analyses were conducted with all datasets, and parameter estimates were pooled using the imputation algorithms in Mplus 8.

Path models in Mplus 8 were used to test associations between intersectional discrimination, resilience, and PrEP use and intentions. The model focused on likelihood of future PrEP use, excluding those who reported being current PrEP users. In both models, directional paths led from intersectional stigma constructs to resilience constructs and PrEP outcomes, and from resilience constructs to PrEP outcomes, in line with our hypotheses. Additionally, paths led from demographic covariates to all constructs. Resilience constructs (resilience, social support, and Black LGBTQ community connectedness) were allowed to correlate with one another.

We fit models using a full information maximum likelihood estimator robust to non-normality (the MLR estimator). Coefficients for predictors that were not associated with outcomes (p > .20) were constrained to zero to increase model parsimony and stabilize estimates. [74] Given this approach, our primary focus was on path coefficients and estimates of indirect effects rather than overall model fit. When testing mediation, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Monte Carlo method in RMediation. [75] This is recommended given the non-normal distribution of indirect effects. We report unstandardized factor loadings, beta coefficients, and odds ratios (ORs). For indirect effects, we also report 95% CIs.

Results

Descriptive information

Based on eligibility criteria, all 283 participants were Black/African American; 8% were multiracial and 7% were Latinx. Most participants (87%) identified as male; the remainder identified as transgender women (11%) or another gender identity (2%). The average age was 22 (SD = 2.75, range = 16–25). With regard to PrEP use, 13% were currently using PrEP and 8% had previously used PrEP. Slightly more than half (56%) of participants enrolled in Milwaukee and the rest in Cleveland (44%). Descriptive statistics related to demographic covariates, stigma, resilience, and likelihood of taking PrEP are summarized in Table 1. Correlations between all study variables are included in Table 2.

Current PrEP use: path model

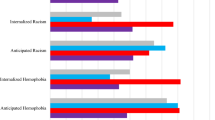

The path model focused on current PrEP use (Fig. 1) showed that participants with higher levels of anticipated discrimination had lower odds of being current PrEP users, OR = 0.59, p = .013. Participants who experienced more day-to-day stigma had higher levels of resilience, B = 0.38 (0.10), p < .001, higher levels of social support, B = 0.37 (0.16), p = .019, and greater connection to the Black LGBTQ community, B = 0.19 (0.07), p = .006. Additionally, participants with more social concerns about PrEP use reported lower levels of resilience, B = -0.19 (0.07), p = .004, and a lower connection to the Black LGBTQ community, B = -0.11 (0.05), p = .013. Participants with more connection the Black LGBTQ community had higher odds of current PrEP use, OR = 2.25, p = .003. There was a significant and positive indirect effect of day-to-day discrimination on current PrEP use via Black LGBTQ community connectedness, B = 0.15 (0.08), 95% CI [0.03, 0.32], p < .01, such that community connectedness fully mediated the association between day-to-day discrimination and PrEP use. Additionally, there was a significant and negative indirect effect of PrEP social concerns on current PrEP use via Black LGBTQ community connectedness, B = -0.09 (0.05), 95% CI [-0.20, -0.01], p < .05, such that community connectedness fully mediated the effects of PrEP social concerns on current PrEP use.

Path model showing associations between intersectional stigma, resilience, and current PrEP use in a sample of young sexual minority men in the Midwest (N = 283). Unstandardized linear regression coefficients (Bs) and odds ratios (ORs) are presented. The model also included correlations between resilience, social support, and Black LGBT community connectedness (paths not shown); there were moderate correlations between the constructs, rs = 0.29–0.40, ps < 0.001. Demographic covariates (age, gender identity, ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, economic hardship, insurance status, number of sexual partners in the past 30 days, psychological distress, enrollment city, and enrollment following the COVID-19 shutdowns) were also included in the model (paths not shown). *** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05

In terms of demographic covariates, participants from Cleveland had lower levels of resilience than those from Milwaukee, B = -0.34 (0.14), p = .018, while those recruited to the study following COVID-19 shutdowns had higher levels of resilience, B = 0.30 (0.16), p = .018. Those with more education and current insurance had higher levels of resilience, B = 0.22 (0.07), p = .002 and B = 0.27 (0.13), p = .039, respectively. Those with higher levels of economic hardship had higher levels of resilience, B = 0.16 (0.07), p = .019. Transgender women and non-binary participants reported lower levels of social support than cis male participants, B = -0.76 (0.32), p = .017, while those with current insurance reported higher levels of social support, B = 0.55 (0.26), p = .032. No demographic covariates were significantly associated with Black LGBTQ community connectedness or with current PrEP use.

Because this path model was fit using the MLR estimator (allowing the report of odds ratios) with mediation and a binary outcome variable, no standard fit indices were available. The model explained 23% of the variance in current PrEP use (p = .006).

Future PrEP use: path model

The path model focused on intentions to use PrEP in the future (Fig. 2), which included only those participants not currently using PrEP (n = 247), showed that individuals who experienced more day-to-day discrimination were more likely to use PrEP in the future, B = 0.48 (0.16), p = .002. Consistent with the current use model, participants who experienced more day-to-day discrimination had higher levels of resilience, B = 0.35 (0.11), p < .001, higher levels of social support, B = 0.44 (0.17), p = .011, and greater connection to the Black LGBTQ community, B = 0.21 (0.07), p = .005. Participants with more social concerns about PrEP use reported a lower connection to the Black LGBT community, B = -0.11 (0.06), p = .037, and were less likely to use PrEP in the future, B = -0.23 (0.09), p = .013. Participants with higher levels of social support were more likely to use PrEP in the future, B = 0.15 (0.05), p = .005. There was a significant and positive indirect effect of day-to-day discrimination on likelihood of future PrEP use via social support, B = 0.07 (0.04), 95% CI [0.01, 0.15], p < .05. This indirect effect indicated that social support partially mediated the effect of day-to-day discrimination on likelihood of future PrEP use.

Path model showing associations between intersectional stigma, resilience, and likelihood of future PrEP use in a sample of young sexual minority men in the Midwest who are not current PrEP users (N = 247). Unstandardized linear regression coefficients (Bs) are presented. The model also included correlations between resilience, social support, and Black LGBT community connectedness (paths not shown); there were moderate correlations between the constructs, rs = 0.30–0.39, ps < 0.001. Demographic covariates (age, gender identity, ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, economic hardship, insurance status, number of sexual partners in the past 30 days, psychological distress, enrollment city, and enrollment following the COVID-19 shutdowns) were also included in the model (paths not shown). *** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05

In terms of demographic covariates, participants recruited to the study following COVID-19 shutdowns reported a lower likelihood of using PrEP in the future compared to those enrolling before the shutdowns, B = -0.60 (0.24), p = .012. Participants who identified as bisexual or as having another sexual orientation reported a lower likelihood of future use compared to gay individuals, B = -0.57 (0.21), p = .006 and B = -0.92 (0.24), p < .001, respectively. Those with higher levels of economic hardship and those with current insurance (vs. no insurance) were more likely to use PrEP in the future, B = 0.21 (0.10), p = .042 and B = 0.73 (0.19), p < .001, respectively. Participants from Cleveland had lower levels of resilience than those from Milwaukee, B = -0.33 (0.14), p = .019. Latinx participants had higher levels of resilience than non-Latinx participants, B = 0.50 (0.17), p = .004. Those with more education, higher levels of economic hardship, and current insurance (vs. no insurance) had higher levels of resilience, B = 0.19 (0.07), p = .007, B = 0.16 (0.07), p = .031, and B = 0.35 (0.13), p = .008, respectively. Those with other sexual orientations had lower levels of resilience compared to those identifying as gay, B = -0.39 (0.18), p = .026. Transgender women and non-binary participants reported lower levels of social support than cis male participants, B = -0.80 (0.34), p = .017, while Latinx participants (vs. non-Latinx participants) and those with current insurance (vs. those without insurance) reported higher levels of social support, B = 0.78 (0.29), p = .008 and B = 0.59 (0.25), p = .021, respectively. Finally, those with sexual orientations other than gay reported lower levels of Black LGBT community connectedness, B = -0.57 (0.13), p < .001.

The model was a good fit to the data, χ2(35, N = 247) = 22.41, RMSEA = < 0.001, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.12, and explained 27% of the variance in likelihood of future PrEP use (p < .001).

Discussion

Despite increasing attention to the effects of intersectional stigma and discrimination on the health of Black SMM and TW, [33, 39, 76, 77] little work has examined how these experiences influence PrEP outcomes. The present study examined the relationship between intersectional discrimination and (1) current PrEP use, and (2) the likelihood of future PrEP use among a sample of YBSMM and TW in two mid-sized Midwestern cities. Further, we examined the potential mediating roles of resilience, social support, and connection to the Black LGBTQ community. While our findings showed some unanticipated relationships, they provide insight into how discrimination and stigma may influence PrEP use and disparities.

Individuals who reported greater anticipated discrimination had lower odds of current PrEP use. Unexpectedly, our results also showed that while major discrimination was not associated with PrEP outcomes, daily experiences of intersectional discrimination in the past year were positively associated with likelihood of future PrEP use. This was surprising and stands in contrast to our qualitative research, which indicated that intersectional racism and homophobia can impede PrEP use among YBSMM. [21, 39] However, this finding does align with other recent studies. For example, research on the relationship between racism and PrEP use found that individuals who reported higher levels of internalized racism were more likely to report PrEP use. [78] Similarly, researchers have found higher levels of internalized homophobia among Black MSM who use PrEP compared to those who do not use PrEP. [79] Sexuality-related discrimination has also been found to be positively associated with PrEP use. [80] Collectively, this research highlights the complexity of stigma and discrimination and requires we move beyond basic assumptions that greater stigma or discrimination necessarily contribute to worse HIV prevention outcomes.

In both models, various aspects of discrimination were also associated with resilience factors. Individuals who experienced more day-to-day discrimination had higher levels of resilience, social support, and connection to the Black LGBTQ community. Individuals who experience greater discrimination may seek out social support and LGBTQ community connections in response to these experiences, which may, in turn, positively impact PrEP outcomes. These social connections can also increase positive perceptions of PrEP and likelihood of current and future use, [81] while mitigating the negative effects of discrimination. Previous research has found that SMM with stronger connections to gay communities may be more likely to know others on PrEP and may also have access to a greater variety of affirming PrEP messages and access. [50]

However, PrEP social concerns, a component of PrEP stigma, was negatively associated with likelihood of future PrEP use. This reflects prior research on PrEP stigma, wherein some individuals associate PrEP with being gay or sexually promiscuous, [39] which may be a deterrent to PrEP use. PrEP social concerns was also negatively associated with Black LGBTQ community connectedness. Higher levels of stigma may weaken connections to LGBTQ communities and in turn limit resources, access, and willingness to use PrEP. Our findings align with prior research highlighting the complexity of connection and attachment to the LGBTQ community, which has been identified to be both a source of risk and resilience with regard to sexual health. [50, 82, 83]

Our results highlight the importance of the Black LGBTQ community in supporting PrEP use for Black SMM and TW. We found that Black LGBTQ community connectedness mediates the effects of day-to-day discrimination and PrEP social concerns on current PrEP use. Connections to Black LGBTQ spaces that support and promote PrEP may increase comfort with the idea of PrEP and help reduce PrEP concerns. Among Black SMM, social support is a common strategy used to cope with racial discrimination. [40, 42] Researchers have found that social support may also be critical in helping sexual and gender minority individuals cope with HIV- and sexuality-related stigma, [84] and that connectedness to the gay community may reduce minority stress and mental distress symptoms. [72] Our findings highlight the importance of supporting and developing LGBTQ affirming spaces for YBSMM and TW to connect, build community, and support one another. Efforts to increase PrEP use among YBSMM and TW should build on existing community resources and networks, particularly Black LGBTQ spaces. Funding initiatives that enhance existing support networks and provide needed support for coping with stigma and discrimination may also support PrEP use among Black sexual and gender minority individuals.

Given the importance of social support and community connectedness identified in this study, it is concerning that trans and gender nonbinary individuals reported lower levels of social support. Similarly, individuals who identified as bisexual or a sexual identity other than gay had lower levels of connectedness to the Black LGBTQ community compared to those who were gay, and they also had a lower likelihood of future PrEP use. This supports prior research demonstrating lower levels of PrEP use among bisexual men compared to gay men. [85, 86] This may also be related to LGBTQ community connectedness and the challenges some bisexual and non-gay-identifying individuals face in navigating gay centric social spaces and obtaining gay community support. [87] These findings highlight the need to support gender and sexually diverse individuals, who may not be receiving support in currently available LGBTQ spaces and communities.

Additional research is needed to better understand the role of resilience, social support, and community connectedness in supporting PrEP use. For example, understanding how Black LGBTQ community connectedness supports PrEP use can provide needed information to grow and support Black LGBTQ community resources. Additionally, we did not find an association between resilience and PrEP outcomes, and future research may help identify aspects of resilience that are unmeasured in this study. Current measures of resilience may be insufficient at capturing all of the experiences of YBSMM and TW, particularly in response to intersectional discrimination, or may not reflect how YBSMM and TW conceptualize resilience. Individuals may elicit greater resilience from social support and community connectedness rather than “coping with stress,” “bouncing back,” or being “able to handle” adversity, the individual-level resilience concepts measured by common resilience measures. [70] Future qualitative research is needed to understand YBSMM’s conceptualizations of and experiences with resilience and coping with discrimination and stigma in order to inform the development of resilience-based interventions.

This study has limitations. First, recruitment extended from 2018 to 2020, spanning a changing political, social, and health care landscape, which may have influenced use and perceptions of PrEP over time. Enrollment was temporarily suspended from March-July 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, our analyses did account for when participants enrolled in the study. Second, the study was dependent on self-report measures, and responses may have been influenced by recall bias or social desirability bias. Related, current and prior PrEP-use were not verified by medical records, and we did not capture length of time on PrEP or reasons for discontinuation. We examined participants’ self-reported likelihood to use PrEP in the future, yet this does not necessarily translate into using PrEP. Additionally, there was no timeframe included in the question about future PrEP use, so it is unclear whether participants were interested in using PrEP in the short- or long-term future. Third, this study’s cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw causal inferences and limits our interpretation of results and ability to determine directionality. It is possible, for example, that limited connection to Black LGBTQ communities contributes to greater PrEP stigma, rather than PrEP stigma weakening connection to Black LGBTQ communities, as identified in this study. Longitudinal research is needed to further test the associations identified in this study and understand how intersectional discrimination influences PrEP uptake and persistence over time. Finally, there remains a lack of consensus about the best ways to quantitatively measure intersectional discrimination. [32, 88] In this study, we used the intersectional discrimination index, given its alignment with intersectionality and focus on any aspects of a participants’ identity. [65] That said, participants may not have been considering their sexual and racial identities when answering the questions.

Importantly, this is one of few studies that have examined how intersectional discrimination relates to PrEP use among young Black sexual minority individuals, and our findings highlight the need for more research on this topic. Specifically, greater attention is needed to the complexities of the relationships between intersectional discrimination, resilience, social support resources, and HIV prevention efforts including PrEP. Finally, an intersectional approach to understanding stigma and discrimination has been critical in advancing our understanding of the effects of discrimination on HIV outcomes for marginalized populations. Stigma scholarship must continue to incorporate intersectional approaches and contribute to the development of intersectional interventions that address multiple mechanisms of stigma.

Citation diversity statement

Recently, researchers have shed light on the racial, ethnic, and gender inequities in citation practices in numerous academic fields. [89,90,91] Research has demonstrated bias in citation practices, such that papers authored by women and racial and ethnic minorities are under cited relative to the number of those papers in the field. Accordingly, during our writing process, we interrogated the literature we read and cited, and aimed to cite research that reflects the diversity of the field in thought, method, and gender, race, and ethnicity of authors. Although this approach is insufficient for addressing these biases, we aim to raise awareness about these inequities and encourage other scholars to examine their citation decisions.

Data Availability

Data will be made available upon request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Change history

12 August 2023

In this article the title was incorrectly given as ‘Intersectional Discrimination and PrEP uSe Among Young Black Sexual Minority Individuals: The Importance of Black LGBTQ Communities and Social Support’ but should have been ‘Intersectional Discrimination and PrEP use Among Young Black Sexual Minority Individuals: The Importance of Black LGBTQ Communities and Social Support’.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Updated). Vol 31.; 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Kaiser Family Foundation. Black Americans and HIV/AIDS. Published 2020. https://www.kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/black-americans-and-hivaids-the-basics/.

Guilamo-Ramos V, Thimm-Kaiser M, Benzekri A, Futterman D. Youth at risk of HIV: the overlooked US HIV prevention crisis. The Lancet HIV. 2019;6(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30037-2.

Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, Higa DH, Sipe TA. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: A systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304727.

Sullivan PS, Smith DK, Mera-Giler R, et al. The impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis with TDF/FTC on HIV diagnoses, 2012–2016, United States. In: 22nd International AIDS Conference.; 2018.

Kanny D, Jeffries W, Chapin-Bardales J, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men – 23 Urban Areas, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:801–806. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6837a2.htm?s_cid=mm6837a2_e&deliveryName=USCDC_921-DM9093&deliveryName=USCDC_1046-DM10139.

Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, et al. Limited Awareness and Low Immediate Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Men Who Have Sex with Men Using an Internet Social Networking Site. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0033119 [doi].

Zablotska IB, Prestage G, de Wit J, Grulich AE, Mao L, Holt M. The informal use of antiretrovirals for preexposure prophylaxis of HIV infection among gay men in Australia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(3):334–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e854a [doi].

Kirby T, Thornber-Dunwell M. Uptake of PrEP for HIV slow among MSM. Lancet. 2014;383(9915):399–400.

Huang YLA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity — United States, 2014–2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Published online 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.15585/MMWR.MM6741A3.

Coy KC, Hazen RJ, Kirkham HS, Delpino A, Siegler AJ. Persistence on HIV preexposure prophylaxis medication over a 2-year period among a national sample of 7148 PrEP users, United States, 2015 to 2017. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25252.

Poteat T, Wirtz A, Malik M, et al. A Gap between Willingness and Uptake: Findings from Mixed Methods Research on HIV Prevention among Black and Latina Transgender Women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002112.

Bauermeister JA, Meanley S, Pingel E, Soler JH, Harper GW. PrEP awareness and perceived barriers among single young men who have sex with men. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(7):520–7. doi:CHRE-EPUB-58855 [pii].

Goedel WC, King MRF, Lurie MN, Nunn AS, Chan PA, Marshall BDL. Effect of racial inequities in pre-exposure prophylaxis use on racial disparities in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men: A modeling study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(3):323–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001817.

Kuhns LM, Hotton AL, Schneider J, Garofalo R, Fujimoto K. Use of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Young Men Who Have Sex with Men is Associated with Race, Sexual Risk Behavior and Peer Network Size. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1376–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1739-0.

Mustanski B, Ryan DT, Hayford C, Phillips IIG, Newcomb ME, Smith JD. Geographic and individual associations with PrEP stigma: Results from the RADAR cohort of diverse young men who have sex with men and transgender women. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3044–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/210461-018-2159-5.

Arnold T, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Chan PA, et al. Social, structural, behavioral and clinical factors influencing retention in Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) care in Mississippi. PLoS ONE. Published online 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172354.

Rolle CP, Rosenberg ES, Siegler AJ, et al. Challenges in Translating PrEP Interest into Uptake in an Observational Study of Young Black MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 76.; 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001497.

Pinto RM, Berringer KR, Melendez R, Mmeje O. Improving PrEP Implementation Through Multilevel Interventions: A Synthesis of the Literature. AIDS and Behavior Published online. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2184-4.

Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Dovidio JF. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):226–40.

Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Zarwell M, Pearson B, Lewis M. “A gay man and a doctor are just like, a recipe for destruction”: How racism and homonegativity in healthcare settings influence PrEP uptake among young Black MSM. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(7):1951–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2375-z.

Bradley E, Forsberg K, Betts JE, et al. Factors Affecting Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Implementation for Women in the United States: A Systematic Review. J Women’s Health. 2019;28(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7353.

He Y, Dangerfield DT, Fields EL, et al. Health care access, health care utilisation and sexual orientation disclosure among Black sexual minority men in the Deep South. Sex Health. 2020;17(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20051.

Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. AIDS. 2015;29(7):837–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000622 [doi].

Rodriguez K, Kelvin EA, Grov C, Meyers K, Nash D, Wyka K. Exploration of the Complex Relationships Among Multilevel Predictors of PrEP Use Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States. AIDS and Behavior Published online. 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03039-1.

Crenshaw KW. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Univ Chic Legal Forum. 1989;139:139–67.

Collins PH. Moving beyond gender: intersecionality and scientific knowledge. In: Feree MM, Lorber J, Hess BB, editors. Revisioning Gender. AltaMira Press; 2000. pp. 261–84.

Bowleg L. When black + lesbian + woman ≠ black lesbian woman: the methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–25.

Collins PH. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Unwin Hyman; 1990.

Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. Published online 1991:1241–1299.

Berger MT. Workable Sisterhood: The Political Journey of Stigmatized Women with HIV/AIDS. Princeton University Press; 2004.

Biello KB, Hughto JMW. Measuring intersectional stigma among racially and ethnically diverse transgender women: Challenges and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306141.

English D, Carter JA, Forbes N, et al. Intersectional Discrimination, Positive Feelings, and Health Indicators Among Black Sexual Minority Men. Health Psychol. 2020;39(3):220–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000837.

Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Landrine H, Klein DJ, Sticklor LA. Perceived discrimination and mental health symptoms among black men with HIV. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2011;17(3):295–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024056.

English D, Rendina HJ, Parsons JT. The effects of intersecting stigma: A longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use Among Black, Latino, and Multiracial Gay and Bisexual Men. Psychol Violence. 2018;8(6):669. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000218.

Harper GW. A journey towards liberation: Confronting heterosexism and the oppression of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered people. In: Community Psychology: In Pursuit of Liberation and Well-Being.; 2010:382–404.

Miller RL. Legacy denied: African American gay men, AIDS and the Black Church. National Association of Social Workers. Published online 2007.

Elopre L, McDavid C, Brown A, Shurbaji S, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM. Perceptions of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Young, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2018.0121.

Quinn K, Bowleg L, Dickson-Gomez J. “The fear of being Black plus the fear of being gay”: The effects of intersectional stigma on PrEP use among young Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Soc Sci Med. 2019;Jul(232):86–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.042.

Choi KH, Han CS, Paul J, Ayala G. Strategies for managing racism and homophobia among U.S. ethnic and racial minority men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prevention: Official Publication Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2011;23(2):145–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2011.23.2.145 [doi].

Han C, Ayala G, Paul JP, Boylan R, Gregorich SE, Choi KH. Stress and coping with racism and their role in sexual risk for HIV among African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with Men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(2):411–20.

Bogart LM, Dale SK, Christian J, et al. Coping with discrimination among HIV-positive Black men who have sex with men. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(7):723–37.

Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev. 2000;71(3):543–62.

Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. ADOLESCENT RESILIENCE: A Framework for Understanding Healthy Development in the Face of Risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26(1):399–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357.

Buttram ME. The social environmental elements of resilience among vulnerable African American/Black men who have sex with men. J Hum Behav Social Environ. 2015;25(8):923–33.

Logie CH, Williams CC, Wang Y, et al. Adapting stigma mechanism frameworks to explore complex pathways between intersectional stigma and HIV-related health outcomes among women living with HIV in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2019;Jul(232):129–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.044.

Cook PF, Schmiege SJ, Bradley-Springer L, Starr W, Carrington JM. Motivation as a Mechanism for Daily Experiences’ Effects on HIV Medication Adherence. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29(3):383–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2017.09.003.

Earnshaw VA, Lang SM, Lippitt M, Jin H, Chaudoir SR. HIV stigma and physical health symptoms: Do social support, adaptive coping, and/or identity centrality act as resilience resources? AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):41–9.

McConnell EA, Janulis P, Phillips G, Truong R, Birkett M. Multiple minority stress and LGBT community resilience among sexual minority men. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2018;5(1):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000265.

Meanley S, Connochie D, Choi SK, Bonett S, Flores DD, Bauermeister JA. Assessing the Role of Gay Community Attachment, Stigma, and PrEP Stereotypes on Young Men Who Have Sex with Men’s PrEP Uptake. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:1761–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03106-7.

Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707.

Wang Y, Lao CK, Wang Q, Zhou G. The Impact of Sexual Minority Stigma on Depression: the Roles of Resilience and Family Support. Sexuality Res Social Policy. 2022;19(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00558-x.

Kalomo EN. Associations between HIV-related stigma, self-esteem, social support, and depressive symptoms in Namibia. Aging and Mental Health. 2018;22(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1387763.

Chakrapani V, Vijin PP, Logie CH, et al. Understanding How Sexual and Gender Minority Stigmas Influence Depression among Trans Women and Men Who Have Sex with Men in India. LGBT Health. 2017;4(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0082.

Handlovsky I, Bungay V, Oliffe J, Johnson J. Developing Resilience: Gay Men’s Response to Systemic Discrimination. Am J Men’s Health. 2018;12(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318768607.

Bowleg L, Huang J, Brooks K, Black A, Burkholder G. Triple jeopardy and beyond: Multiple minority stress and resilience among Black lesbians. J Lesbian Stud. 2003;7(4):87–108.

Greene B. Ethnic-Minority Lesbians and Gay Men: Mental Health and Treatment Issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.243.

Logie CH, Wang Y, Marcus NL, et al. Pathways from sexual stigma to inconsistent condom use and condom breakage and slippage among MSM in Jamaica. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(5):513–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001712.

Storholm ED, Huang W, Siconolfi DE, et al. Sources of Resilience as Mediators of the Effect of Minority Stress on Stimulant Use and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Young Black Men who have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02572-y.

Ohio Department of Health. Summary of HIV Infection Among Blacks/African-Americans in Ohio.; 2019.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services Division of Public Health HIV Program. HIV in Wisconsin: Wisconsin HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2018.; 2019.

Mena L, Crosby RA, Geter A. A novel measure of poverty and its association with elevated sexual risk behavior among young Black MSM. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462416659420.

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074.

Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2014;49(2):177–86.

Scheim AI, Bauer GR. The Intersectional Discrimination Index: Development and validation of measures of self-reported enacted and anticipated discrimination for intercategorical analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2019;226:225–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.016.

Jeffries 4th WL. Marks G, Lauby J, Murrill CS, Millett GA. Homophobia is Associated with Sexual Behavior that Increases Risk of Acquiring and Transmitting HIV Infection Among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1442–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0189-y.

Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, Walters K. Measuring multiple minority stress: the LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2011;17(2):163.

Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, Conway-Washington C. Minimal Awareness and Stalled Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among at Risk, HIV-Negative, Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(8). doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2014.0303.

Walsh JL. Applying the Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills Model to Understand PrEP Intentions and Use Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and Behavior Published online. 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2371-3.

Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new Resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113.

Canty-Mitchell J, Zimet GD. Psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in urban adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 2000;28(3):391–400.

Frost DM, Meyer IH. Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. J Sex Res. 2012;49(1):36–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.565427.

Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7th ed.: Muthen & Muthen; 2015.

Bentler PM, Mooijaart A. Choice of Structural Model via Parsimony: A Rationale Based on Precision. Psychol Bull. 1989;106(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.315.

Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. Monte Carlo Confidence Intervals for Complex Functions of Indirect Effects. Struct Equ Model. 2016;23(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2015.1057284.

Earnshaw VA, Reed NM, Watson RJ, Maksut JL, Allen AM, Eaton LA. Intersectional internalized stigma among Black gay and bisexual men: A longitudinal analysis spanning HIV/sexually transmitted infection diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2021;26(3):465–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318820101.

Remedios JD, Snyder SH. Intersectional Oppression: Multiple Stigmatized Identities and Perceptions of Invisibility, Discrimination, and Stereotyping. J Soc Issues. 2018;74(2):265–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12268.

Whitfield DL. Does internalized racism matter in HIV risk? Correlates of biomedical HIV prevention interventions among Black men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2020;32(9):1116–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1753007.

Eaton LA, Matthews DD, Driffin DD, Bukowski L, Wilson PA, Stall RD. A Multi-US City Assessment of Awareness and Uptake of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Prevention Among Black Men and Transgender Women Who Have Sex with Men. Prev Sci Published online. 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0756-6.

Meanley S, Chandler C, Jaiswal J, et al. Are sexual minority stressors associated with young men who have sex with men’s (YMSM) level of engagement in PrEP? Behav Med. 2020;May 13:1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2020.1731675.

Hotton AL, Keene L, Corbin DE, Schneider J, Voisin DR. The relationship between Black and gay community involvement and HIV-related risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. Published online 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2017.1408518.

Carpiano RM, Kelly BC, Easterbrook A, Parsons JT. Community and drug use among gay men: The role of neighborhoods and networks. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395026.

Petruzzella A, Feinstein BA, Davila J, Lavner JA. Moderators of the Association Between Community Connectedness and Internalizing Symptoms Among Gay Men. Arch Sex Behav. 2019;48(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1355-8.

Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Broaddus M, Kelly JA. “It’s almost like a crab-in-a-barrel situation”: Stigma, social support, and engagement in care among black men living with HIV. AIDS Educ Prev. 2018;30(2):120–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2018.30.2.120.

Zarwell M, John SA, Westmoreland D, et al. PrEP Uptake and Discontinuation Among a U.S. National Sample of Transgender Men and Women. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(4):1063–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03064-0.

Hammack PL, Meyer IH, Krueger EA, Lightfoot M, Frost DM. HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use, familiarity, and attitudes among gay and bisexual men in the United States: A national probability sample of three birth cohorts. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202806.

Friedman MR, Bukowski L, Eaton LA, et al. Psychosocial Health Disparities Among Black Bisexual Men in the U.S.: Effects of Sexuality Nondisclosure and Gay Community Support. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2019;48(1):213–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1162-2.

Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med. 2019;17(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9.

Chatterjee P, Werner RM. Gender Disparity in Citations in High-Impact Journal Articles. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7). doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14509.

Bertolero MA, Dworkin JD, David SU, et al. Racial and ethnic imbalance in neuroscience reference lists and intersections with gender. bioRxiv. Published online 2020.

Dworkin JD, Linn KA, Teich EG, Zurn P, Shinohara RT, Bassett DS. The extent and drivers of gender imbalance in neuroscience reference lists. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(8). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-020-0658-y.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the contributions of the study team members at the Center for AIDS Intervention Research and the AIDS Taskforce of Greater Cleveland. This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH112412; Quinn; K01-MH118939, PI: John). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (K01 MH112412; Quinn; K01-MH118939, PI: John).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KQ was the PI on the study and conceived of the analysis and drafted the manuscript; JDG provided feedback on study design and analysis and substantial feedback on the manuscript; AC provided substantial input into the analyses and feedback on the manuscript; SJ provided substantial feedback on the manuscript; JW conducted analysis, wrote components of the paper, and provided substantial feedback on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Consent to participate

All participants consented to participate; we received a waiver of documented consent and a waiver of parental consent for individuals under age 18.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Quinn, K.G., Dickson-Gomez, J., Craig, A. et al. Intersectional Discrimination and PrEP use Among Young Black Sexual Minority Individuals: The Importance of Black LGBTQ Communities and Social Support. AIDS Behav 27, 290–302 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03763-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03763-w