Abstract

HIV testing and counseling (HTC) in antenatal care is extremely effective at identifying women living with HIV and linking them to HIV care. However, retention is suboptimal in this population. We completed qualitative interviews with 24 pregnant women living with HIV in Tanzania to explore perceptions of HTC. Participants described intense shock and distress upon testing positive, including concerns about HIV stigma and disclosure; however, these concerns were rarely discussed in HTC. Nurses were generally kind, but relied on educational content and brief reassurances, leaving some participants feeling unsupported and unprepared to start HIV treatment. Several participants described gaps in HIV knowledge, including the purpose of antiretroviral therapy and the importance of medication adherence. Targeted nurse training related to HIV disclosure, stigma, and counseling skills may help nurses to more effectively communicate the importance of care engagement to prevent HIV transmission and support the long-term health of mother and child.

Resumen

Las pruebas de VIH y la orientación (HTC) en el cuidado prenatal son métodos extremadamente efectivos para identificar a mujeres viviendo con VIH y referirlas al cuidado que necesitan. Sin embargo, la retención en los programas de cuidado es un obstáculo en esta población. Completamos entrevistas cualitativas en Tanzania con 24 mujeres embarazadas que viven con el VIH para identificar sus reacciones al HTC. Las participantes describieron un sentido de conmoción intensa y angustia al dar positivo, además de las preocupaciones sobre el estigma del VIH y el temor a divulgar ser positivas. Sin embargo, estas preocupaciones rara vez se discutieron durante el proceso de HTC. Por lo general, las enfermeras fueron amables, pero se dependían del material educativo y ofrecían pequeñas consolaciones, los cuales dejaban a algunas participantes sintiéndose sin apoyo y sin preparación para comenzar el tratamiento contra el VIH. Varias participantes describieron poco conocimiento del VIH, como el propósito de la terapia antirretroviral y la importancia de la adherencia terapéutica. Un entrenamiento específico para las enfermeras en relación a la divulgación, el estigma y la orientación sobre el VIH podrían ayudar a las enfermeras a comunicar de manera más efectiva la importancia de la participación en el cuidado de la condición para así prevenir la transmisión del VIH y fomentar la salud a largo plazo del la madre y la criatura.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Universal HIV testing during antenatal care is a key catch point for HIV diagnosis, counseling, and the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in many nations throughout the world [1]. In 2012, the World Health Organization introduced Option B+, a policy that all pregnant women living with HIV should be started on ART, regardless of CD4 count or clinical stage, and continue for lifetime use [2]. In the years following its introduction, Option B+ has been taken to scale, starting with 21 UNAIDS Global Plan priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa, including Tanzania [3].

By 2017, the Option B+ policy had facilitated the initiation of ART in over 900,000 women living with HIV worldwide, and contributed to UNAIDS Global Plan progress in preventing 1.2 million new infections among children [3, 4]. Studies of Option B+ have found that the program leads to earlier linkage to HIV care among women, reductions in mother-to-child transmission, increased ART coverage at the community level, and improved health outcomes for both the mother and child [5, 6] In Tanzania, the policy became part of the national strategy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and was fully implemented by the end of 2014 [7, 8].

Although the Option B+ policy has been successful at extending the reach of HIV testing and linkage to care, there are some important limitations to consider. A recent meta-analysis of studies conducted in Africa suggests that women enrolled in PMTCT programs under Option B+ have higher rates of loss to follow-up than the general population of people living with HIV (PLWH) [9]. A large portion of this difference can be explained by low treatment uptake following a diagnosis in antenatal care and high loss to follow-up in the first months after being linked to HIV treatment [9,10,11]. Because HIV testing is conducted when women are presenting for a non-HIV healthcare service (antenatal care), those who test positive for HIV may be less emotionally prepared to accept the test result, which may contribute to hesitancy or fear to initiate lifelong treatment immediately upon diagnosis [6].

Thus, for women who test positive for HIV during antenatal care, a positive experience with HIV testing and counseling (HTC) is a critical first step to promoting long-term HIV care engagement [12]. Additionally, among women who test negative, HTC provides an opportunity for education about the importance of safe sexual practices, regular testing, and stigma reduction [13]. For women with a pre-established HIV diagnosis, a confirmatory HIV test is generally not given during pregnancy, but antenatal care provides an opportunity to assess ART adherence and provide additional counseling or education. HIV testing and counseling is based on a confidential dialogue with a healthcare worker, and it involves preparing the patient for an HIV test, completing the test, communicating the results, and providing post-test support and education [14]. Among women who test positive for HIV, Tanzanian national policy indicates that post-test counseling should include the provision of emotional support to accept the diagnosis, education about HIV and antiretroviral therapy, adherence counseling, conversations about HIV disclosure, and discussions about implications for delivery, breastfeeding, and the long-term health of mother and child [15].

Increasingly, Tanzanian clinics are encouraging pregnant women to bring the father of the child to the first antenatal care appointment, where he will also participate in HIV testing and counseling [16]. If a pregnant woman or her partner tests positive, nurse-counselors provide a direct referral to a PMTCT Clinic for the woman or a Care and Treatment Clinic (CTC) for the partner, typically housed in the same health center. HIV clinics in Tanzania provide all HIV care, including antiretroviral therapy, free of charge, and patients are encouraged to initiate medication on the same day or within 1 week of an HIV diagnosis [17]. These policies are part of a “multi-sectoral approach” to offer co-located HIV services aimed at “full integration of HIV prevention, care and treatment services, and maternal nutrition, newborn, child, adolescent health, and other reproductive health programs” delivered entirely within HIV clinics [8].

In Tanzania and most other African nations, HTC is primarily provided by nurses. In the Tanzanian antenatal care setting, nurses typically receive initial on-the-job training in HTC with occasional updates and refresher trainings. For example, the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation led training efforts for nurses to prepare for the roll-out of the Option B+ policy [18, 19]. Despite clear efforts to provide high-quality HTC services, many nurses describe lacking the time to effectively counsel patients due to conflicting demands with their other duties [20]. This reality is exacerbated by the lack of trained professional nurses and high demand for their services in low-resource healthcare settings [21, 22]. When HIV counseling is perceived as insufficient, patients describe struggling with unanswered questions, doubts about the validity of the information provided, and uncertainty about how to put the information into action in their daily lives [23, 24].

When done effectively, HTC in antenatal care has a direct benefit to all women, regardless of their HIV status, as it may reduce stigma, assist those with negative test results to remain uninfected, and support those living with HIV to minimize the medical, social, and emotional impacts of HIV [25, 26]. However, there is currently a notable gap in the literature examining the content of nurse-delivered HTC, its effectiveness, and how it is received by women seeking antenatal care. This qualitative study sought to elicit the perspectives of PMTCT patients regarding the content and quality of the counseling they received during HTC in Tanzania. These insights can help to identify opportunities to improve counseling in the antenatal care setting, which may contribute to improved health outcomes.

Methods

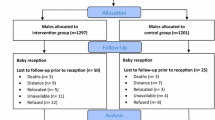

We completed semi-structured in-depth interviews with 24 pregnant women living with HIV between July of 2016 and August of 2017. Participants were recruited from a broader parent study of pregnant women living with HIV in the Moshi district of Tanzania [27]. Pregnant women living with HIV were enrolled from the PMTCT clinics of a tertiary hospital and two urban health centers in the district, where the prevalence of HIV among pregnant women is 4.8%. The three study sites operate under the Tanzanian National AIDS Control Program, which provides free clinical services and antiretroviral treatment to all patients living with HIV [15]. All study clinics had implemented the Option B+ policy by the start of enrollment.

Participants were eligible to complete in-depth interviews if they were at least 16 weeks pregnant, at least 18 years old, fluent in Kiswahili, had been in HIV care for at least 1 month, and were capable of understanding and providing written informed consent. The consent form was read aloud in Kiswahili and participants were provided with a copy. Participants were encouraged to ask questions. Those unable to write were able to provide a thumbprint in the presence of a witness to indicate their consent.

Participants were purposively selected from the broader cohort to include the perspectives of both women newly diagnosed with HIV during the current pregnancy and those with an earlier, established diagnosis at the time of entry into antenatal care; ten participants had established HIV diagnoses and fourteen were newly diagnosed during the current pregnancy. Interviews were completed in Kiswahili by a trained Tanzanian research nurse, lasted approximately 60 min, and were audio recorded for later transcription. All participants provided their informed consent prior to the interviews. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) and the institutional review boards of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre and Duke University. This manuscript was prepared according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [28].

Qualitative Interview Guide

The semi-structured interview guide was developed through an iterative process, incorporating prior literature, formative data collected from providers and patients, and research team members’ clinical experience in HIV care. We received feedback on a preliminary version from people living with HIV who are members of a local study advisory board and finalized the guide during training and practice sessions with the study nurses. The final interview guide included questions and prompts aimed at exploring the participant’s experiences with HTC. For women with established HIV diagnoses or those who had participated in HTC during more than one pregnancy, they were encouraged to share their experiences across all the times they had participated. The guide included prompts relating to their emotional response to receiving a positive test result, the demeanor and communication style of the nurse providing HTC, and the content of the counseling they received after testing positive. Specific prompts probed further into about counseling related to antiretroviral treatment, adherence and care engagement, PMTCT, social support and coping, labor and delivery, and care of the baby after birth, including breastfeeding. Finally, participants were asked to discuss their overall satisfaction with HTC and with the nurse-counselor, and to provide feedback for areas of improvement.

Researcher Characteristics, Training, and Reflexivity

The research was conducted by a diverse team of Tanzanian and U.S.-born researchers. The informed consent procedures and qualitative interviews were conducted by two Tanzanian study nurses; study nurses were members of the research team and not clinic staff, but worked closely with clinic staff in managing participant recruitment and referral. Both study nurses had extensive prior experience in conducting qualitative research. They received 2 weeks of face-to-face training to build expertise in qualitative research, gain familiarity with the qualitative interview guide, and practice administering interviews. They were required to complete a final mock interview prior to any contact with participants. Tanzanian study team members were equal partners in the analysis, interpretation, and reporting of findings.

Data Analysis

The audio recordings were transcribed and translated to English by a trained Tanzanian interpreter, and a random subset were reviewed for accuracy by a research team member fluent in Kiswahili. Data were analyzed through a team-based, thematic approach informed by grounded theory and the constant comparative method [29, 30]. Each transcript was first reviewed by two research team members to identify the broader domains represented in the data and informed by the qualitative interview guide. Next, the researchers developed a qualitative memo for each interview which served to summarize the interview and track content related to the topic onto the relevant domains [31]. The memos were then transferred to NVivo software and coded to develop inductive themes, linking the memo content to respective themes. To facilitate trustworthiness and to ensure reproducibility, each memo was coded by one team member and checked by another, and all discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. A subset of five memos were randomly selected to be re-coded by a third team member and checked for inter-coder agreement using a pre-established threshold of 80% [32]. All five coded memos exceeded the desired threshold for inter-coder agreement (range: 82–93%).

Results

Participants

The 24 participants in the study ranged from 18 to 43 years old, with the mean age of 29. Fourteen participants (58.3%) were newly diagnosed with HIV during the current pregnancy, and ten (41.7%) had established HIV diagnoses at the time of entry into ANC. Sixteen (66.7%) were married, six (25.0%) were unmarried but in a relationship, and two (8.3%) were not in a relationship. Fifteen participants (62.5%) knew the HIV status of the father of the child, and seven (29.2%) reported that they were in a sero-discordant relationship (i.e., their partner was HIV-negative). Among the 14 women newly diagnosed with HIV during this pregnancy, 6 tested with a male partner; 3 of these male partners tested positive for HIV and 3 tested negative.

The final themes that emerged in the data analysis included the participants’ responses to receiving an HIV diagnosis, her perceptions of the demeanor of the nurses who provided HTC, the content of the counseling, the emotional support she received, and subsequent challenges or barriers she faced to linkage or retention in HIV care (see Table 1).

Response to HIV Diagnosis

In describing their response to learning about their HIV diagnosis during HIV testing and counseling, most participants said they were shocked, afraid, and panicked. About one-third of participants described extreme sadness, depression, and hopelessness, often sparked by a fear of death from HIV. One participant shared, “Before [antiretroviral treatment became available], you knew that once you get HIV you just die, nothing else. So, I panicked badly when I was told I had HIV. I saw that my journey had come to an end." In the interviews, three participants acknowledged thoughts of suicide after learning their HIV status. Of the three patients who had experienced suicidal ideation, none had been asked about thoughts of suicide during HIV testing and counseling, and none had shared this information with a nurse or other healthcare worker.

Other participants described feelings of denial and struggling to accept that they were HIV-positive, sometimes for days or weeks after the diagnosis. Two participants acknowledged that they went to another clinic for a confirmatory test before they were willing/able to accept the results.

At first, I didn’t believe it was true because I didn’t cheat on our marriage. I refused to take the medication; I said no because I was feeling very healthy…I have never been sick in my life, so I had doubts about the medications. Being informed about my HIV status was a very hard thing for me to believe. It distressed me and I wasn’t able to accept it.

Several participants said that when they learned of their diagnosis, they were fearful that they might transmit to the virus to their baby and/or partner, while others expressed concern that they would not be able to work and support their children. Women whose partner did not know their HIV status described substantial worry and distress surrounding when and how they might choose to disclose, while women who tested with their partner expressed relief that they could be open with one another about the illness. Several participants expressed that they made an effort to embrace feelings of acceptance and normalcy soon after receiving the HIV diagnosis. For example, one woman shared,

I never expected a result like this…I mean, you are walking around and you are alive, but you are suffering from something that you don’t know about. But when I was told I just accepted it, because when I look around there are so many people who have HIV, and they are alive and they are using the medicine and we just see them as normal.

Demeanor of the Healthcare Worker

When asked about the demeanor of the nurse who provided HIV testing and counseling, participants most often described the person as kind, supportive, helpful, or concerned. As one participant described, “Yes, the nurse was helpful. She was kind to me…she gave me the medicine and explained how to take them. She also told me that whenever I have a problem I should tell her.”

Two participants described the nurse as nervous or uneasy when giving the results of the HIV test and providing counseling and education. As one participant shared, “[The nurse] was clearly shocked as she was telling me [my positive result]. She was finding it difficult to tell me. When she saw the results, she was really startled.” In instances where participants had a negative or uneasy perception of the nurse’s demeanor, they also commonly reported feeling uncomfortable asking questions, or were worried about their HIV outcomes. Participants who reported feeling less comfortable with the nurse also commonly said they left the initial session feeling uninformed about important topics such as reducing transmission risk, medication adherence, and breastfeeding.

Content of Counseling

In discussing the content of counseling, participants were primarily focused on post-test counseling and provided little information about pre-test counseling. After receiving their test result, participants most commonly described receiving didactic education from the nurse. They noted that they received practical information about HIV and treatment, with a particular emphasis on the importance of medication and daily adherence to antiretroviral treatment. One participant shared, “They advised me to take my medicine on time, and that I would have to take the medicine for the rest of my life. That is it." Many participants also received information about minimizing the risk of transmission to the baby. Several described receiving education about breastfeeding and reassurance that they would be able to breastfeed their baby as normal. Among women who were in a discordant relationship or did not know their partner’s status, counseling commonly centered around prevention of transmission to the partner and the need to use condoms and other safe sex practices. Overall, when women were asked generally about the content of HTC, there was a notable absence of discussion of emotional support or mental health, little guidance on managing HIV stigma, and minimal support in navigating HIV disclosure to the father of the child or others.

Emotional Support in HIV Testing and Counseling

When asked specifically whether they felt emotionally supported in HTC, most of the women we interviewed said they received “reassurance” from the nurses that the outcomes would not be as bad as they feared. This included reassurance that they could live a long, full life and that they could deliver a healthy, uninfected baby. “They told me that if I will concentrate on using the medicine, I will give birth to a baby that’s free of the infection." Nurses also commonly encouraged patients to “be strong” and “don’t worry.” In some instances, patients described this approach as helpful in providing them with encouragement and hope.

The nurse just gave me some hope that I wasn’t the only one out there who was infected, that there are many people who are infected like myself. And also, she encouraged me that if you use the medicine, it isn’t that this is the end of your life…no.

However, some other patients described the nurse’s stance that they should “be strong” and “don’t cry” as dismissive of the feelings of shock, fear, and sadness they were experiencing. In some instances, patients felt the brevity of counseling was due to the busy clinic schedule and the fact that the nurses needed to see such a large number of patients. Women were commonly told not to worry, not to think too much, and not to be afraid, sometimes in an abrupt way that did not acknowledge the seriousness of the emotional impact of receiving a new HIV diagnosis. As one woman shared, “They comfort you just fine. They tell you don't cry, don’t worry, you will live.” Another participant shared a similar experience: “They told me not to worry and that I was not sick, it was just deficiency of immunity in the body.”

Challenges Experienced in HIV Testing and Counseling

About half of participants described a challenging experience during HIV testing and counseling, with the most common being that they had unanswered questions about their health at the end of the session. This included receiving inadequate or inaccurate information about topics such as how long they needed to take antiretroviral medication, why they needed to take medication, how their HIV might impact their delivery, and how long they should breastfeed their baby. One participant said she did not feel comfortable asking questions because there were student nurses present in the session, while several others acknowledged that they simply felt too emotionally overwhelmed by the diagnosis to understand the counseling that was provided or to ask questions after receiving their diagnosis.

I tell you, I ended up being very weak and even if you asked me something I found my head was not working. I mean, I didn’t have the strength to ask someone questions. I was so weak I couldn’t ask. I was so hurting.

In some cases, clinic staff took steps to remedy these challenges. For example, one participant shared that a nurse took the time to follow up with her at her next appointment when she felt more emotionally prepared to receive information about her diagnosis, and that she came to understand better at that time:

On that first day, I didn’t come away with anything other than that I will have to swallow the pills for the rest of my life and that I shouldn’t skip. That’s the only thing I came out with. The rest I didn’t catch at all. Later when I sat with the nurse, she explained it to me. I came to know the meaning of the medicine.

Discussion

HIV testing and counseling (HTC) during antenatal care is an important opportunity for identifying women living with HIV, connecting with women who have been previously diagnosed but are not taking antiretroviral medication, and engaging both groups in care. However, studies have observed greater loss to follow-up among pregnant and postpartum women as compared to the general population of people living with HIV [9]. In Tanzania, HTC is provided by clinic nurses who face a variety of challenges, including high demand for services and resource constraints [22]. Further, there is wide variation in the training nurses receive in counseling, and training is typically focused on providing information related to medication and preventing transmission; there is much less emphasis on how to provide effective emotional support, discuss disclosure, and address HIV stigma; this critical lack of training may contribute to reduced confidence among nurses in addressing these topics in HTC [33, 34]. Understanding the perspectives of patients who undergo HIV testing in antenatal care serves to identify areas of need and inform how testing and counseling can be improved to better serve the needs of patients.

In our qualitative interviews with pregnant women living with HIV in Tanzania, women shared their experiences of HTC in antenatal care, the counseling and education received, and their perceptions of the quality of services. Upon learning of their HIV diagnosis, newly diagnosed women described intense feelings of shock, distress, fear, and worry. Nurses were generally considered supportive and kind, but many participants felt that nurses did not spend the time necessary to provide adequate HIV education and emotional support. Nurses instead relied on brief education on specific topics (e.g., adherence and breastfeeding) and brief reassurances that did not acknowledge the complex and nuanced challenges of receiving a new HIV diagnosis. Together, these findings are similar to earlier studies from Uganda and Tanzania that showed time and resource limitations may hinder post-test counseling from having a positive impact on health behavior and may instead contribute to feelings of uncertainty and doubt [23, 24].

The interviews revealed several missed opportunities in current HIV testing and counseling practice related to counseling, education, and emotional support. Several participants described gaps in their knowledge of HIV that were not addressed in counseling, including a lack of understanding of the rationale for antiretroviral treatment, that they should remain in treatment for life, and how HIV might impact their labor, delivery, and breastfeeding. The topic of how and when to disclose one’s HIV status to sexual partners and/or family members was also rarely discussed. Similar to other settings, a key contributor to these limitations may be the high demands placed on nurses’ time, which allowed for only brief interaction with the patient after communicating the test results [35].Women who completed HIV testing with a male partner described relief in this opportunity to be open about their HIV status, despite accompanying stress. It is unclear from these data whether nurses had adequate training to offer more effective counseling, and this will be an important area of future study [36].

The findings highlight the potential to improve person-centered education and emotional support in the antenatal care setting. In our interviews, many women described feeling too emotionally overwhelmed to appropriately absorb the information being offered to them in HIV testing and counseling. This may point to the need to first address the emotional challenge of accepting an HIV diagnosis before shifting focus to the more educational components of counseling, as well as the need to repeat and reinforce key information at future clinic appointments when the patient is likely to be better prepared to absorb the information and make long-term decisions that will promote her health and well-being [36, 37].

Task-shifting may help alleviate some of the burden of counseling from nurses and present an opportunity for comprehensive education and support from trained lay counselors. Lay counselors in Zambia who provided HIV testing and counseling services were both motivated and confident, demonstrating high quality of counseling, while significantly reducing the workload for healthcare workers [38]. Other examples of lay counselor support for HIV testing and counseling in South Africa show promising outcomes when counselors are equipped with proper training in counseling skills, supervision support, and integration into the formal healthcare system [39]. The lay counselor model could be adapted and integrated into ANC care to provide additional support for women who test positive for HIV during pregnancy.

Antenatal care provides a unique opportunity for testing, diagnosis, and counseling related to HIV, which are integral components of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs and critical to promoting care engagement in the first months after a diagnosis [7]. Women are encouraged to return to the clinic to check on the progress of the pregnancy and to obtain antiretroviral medication refills, and health workers can use these visits as an opportunity to provide additional education and counseling. Based on our findings and the existing literature, areas that may require additional attention include managing HIV stigma [40], offering mental health screening and treatment [41], and facilitating selective and appropriate HIV disclosures to a partner, friend, or family members to recruit social support [42]. Specific emphasis should be placed on mental health comorbidities which have been found to hinder HIV care engagement, including depression, anxiety, and traumatic stress [43,44,45]. Effective HIV counseling should not only enhance patient knowledge and skills that are applicable within the clinic, but should also foster healthy coping and social support in the patient’s daily life, which have been shown to be critical for long-term HIV care engagement and medication adherence[46].

The findings should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. Interviews were conducted with a small cohort of adult women living in a single city in northern Tanzania; therefore, results may not be generalizable to other samples and settings. To minimize the emotional burden this interview might place on women immediately after receiving a diagnosis, all interviews were conducted at least 30 days after the initial diagnosis; some women with an established HIV diagnosis had been diagnosed many years prior to study enrollment. Therefore, it is likely that there were issues of recall bias related to past experiences with HIV testing and counseling. The study also missed women who were lost to follow up on the first month after diagnosis. It is likely that women who dropped out of care during this critical window would have shared different and more negative experiences with HTC, which will be important to explore in future research.

Conclusions

Antenatal care is an important setting for HIV testing and counseling, and the implementation of Option B+ has led to advances in linking pregnant women living with HIV to lifelong care. However, women enrolled in Option B+ are more likely to drop out of care in the first months of treatment as compared to the general population of people living with HIV. Our results indicate that patients may feel overwhelmed immediately upon learning of a new HIV diagnosis, making it difficult for them to absorb counseling content and commit to long-term treatment. Further, limitations in time, human resources, and training may prevent nurses from offering high-quality counseling, particularly in low-resource settings. These findings point to the need for having targeted training in critical aspects of counseling in PMTCT care, including HIV disclosure, stigma, and effectively communicating the importance of care engagement to prevent HIV transmission and support the long-term health of mother and child. The scale-up and improvement of task-shifting programs that integrate lay counselors to support HIV counseling and treatment are also a promising avenue for PMTCT programming.

References

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: Recommendations for a public health approach (Second edition). Geneva: WHO; 2016. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/208825/1/9789241549684_eng.pdf?ua=1

World Health Organization. Programmatic update: Use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: https://www.who.int/hiv/PMTCT_update.pdf

Haroz D, von Zinkernagel D, Kiragu K. Development and impact of the global plan. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75:17–26.

Kalua T, Tippett Barr BA, van Oosterhout JJ, Mbori-Ngacha D, Schouten EJ, Gupta S, et al. Lessons Learned From Option B+ in the Evolution Toward “Test and Start” From Malawi, Cameroon, and the United Republic of Tanzania. JAIDS JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017; Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2017/05011/Lessons_Learned_From_Option_B__in_the_Evolution.7.aspx

Kim MH, Ahmed S, Hosseinipour MC, Giordano TP, Chiao EY, Yu X, et al. Implementation and operational research: the impact of option B+ on the antenatal PMTCT cascade in Lilongwe. Malawi J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 Apr 15;68(5):e77–83.

Myer L, Phillips TK. Beyond “Option B+”: understanding antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, retention in care and engagement in ART services among pregnant and postpartum women initiating therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017 Jun;1(75):S115–S12222.

Gamell A, Luwanda LB, Kalinjuma AV, Samson L, Ntamatungiro AJ, Weisser M, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV Option B+ cascade in rural Tanzania: the one stop clinic model. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0181096.

The United Republic of Tanzania. Tanzania Elimination of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV Strategic Plan II: 2018–2021. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly, and Children; 2017. Available from: https://www.moh.go.tz/en/pmtct-publications

Knettel BA, Cichowitz C, Ngocho JS, Knippler ET, Chumba LN, Mmbaga BT, et al. Retention in HIV care during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the option B+ era: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018 Apr;77(5):427–38.

Cichowitz C, Mazuguni F, Minja L, Njau P, Antelman G, Ngocho J, et al. Vulnerable at each step in the PMTCT care cascade: high loss to follow up during pregnancy and the postpartum period in Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2298-8.

Mazuguni F, Mwaikugile B, Cichowitz C, Watt MH, Mwanamsangu A, Mmbaga BT, et al. Unpacking loss to follow-up among HIV-infected women initiated on option B+ in Northern Tanzania: a retrospective chart review. EA Health Res J. 2019;3(1):6–15.

Gunn JKL, Asaolu IO, Center KE, Gibson SJ, Wightman P, Ezeanolue EE, et al. Antenatal care and uptake of HIV testing among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20605.

American Psychological Association. Counseling in HIV Testing Programs. 2014. Available from: https://www.apa.org/about/policy/counseling.aspx

National comprehensive guidelines for HIV testing and counselling. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; 2013. Available from: https://aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/htc_tanzania_2013.pdf

Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. National guidelines for comprehensive care services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and keeping mothers alive. 2013.

Nyamhanga T, Frumence G, Simba D. Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in Tanzania: assessing gender mainstreaming on paper and in practice. Health Policy Plan. 2017 Dec;32(Suppl 5):v22–30.

Mateo‐Urdiales A, Johnson S, Smith R, Nachega JB, Eshun‐Wilson I. Rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6575156/. Accessed 27 July 2019.

Chumba LN. Facility-level factors affecting implementation of the Option B+ protocol for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. 2018; https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/17002. Accessed 17 Aug 2017.

EGPAF. Tanzania Program 2014 Annual Report-EGPAF. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation; 2014. Available from: https://www.pedaids.org/resource/tanzania-program-2014-annual-report/

Phiri N, Tal K, Somerville C, Msukwa MT, Keiser O. “I do all I can but I still fail them”: health system barriers to providing Option B+ to pregnant and lactating women in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2019 Sep 12;14(9):e0222138.

Agarwal R, Rewari BB, Allam RR, Chava N, Rathore AS. Quality and effectiveness of counselling at antiretroviral therapy centres in India: capturing counsellor and beneficiary perspectives. Int Health. 2019;11:480–6.

Campbell C, Scott K, Madanhire C, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. A ‘good hospital’: Nurse and patient perceptions of good clinical care for HIV-positive people on antiretroviral treatment in rural Zimbabwe: a mixed-methods qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011 Feb;48(2–3):175–83.

Lyatuu MB, Msamanga GI, Kalinga AK. Client satisfaction with services for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Dodoma rural district. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5(3):174–9.

Rujumba J, Neema S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T, Heggenhougen HK. Pregnant women’s experiences of routine counselling and testing for HIV in Eastern Uganda: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013 May 24;13(1):189.

DiCarlo AL, Gachuhi AB, Mthethwa-Hleta S, Shongwe S, Hlophe T, Peters ZJ, et al. Healthcare worker experiences with Option B+ for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in eSwatini: findings from a two-year follow-up study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019 Apr 2;19(1):210.

Meursing K. HIV counselling: a luxury or necessity? Health Policy Plann. 2000 Mar 1;15(1):17–23.

Watt MH, Cichowitz C, Kisigo G, Minja L, Knettel BA, Knippler E, et al. Predictors of postpartum HIV care engagement for women enrolled in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs in Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2019 Jun 3;31(6):687–98.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014 Sep;89(9):1245.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2014.

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2012.

Birks M, Chapman Y, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J Res Nurs. 2008 Jan 1;13(1):68–75.

Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, Pedersen OK. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Methods Res. 2013 Aug 1;42(3):294–32020.

Leshabari SC, Blystad A, de Paoli M, Moland KM. HIV and infant feeding counselling: challenges faced by nurse-counsellors in northern Tanzania. Hum Resour Health. 2007 Jul;24(5):18.

Watson-Jones D, Balira R, Ross DA, Weiss HA, Mabey D. Missed opportunities: poor linkage into ongoing care for HIV-positive pregnant women in Mwanza, Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40091.

Delva W, Mutunga L, Quaghebeur A, Temmerman M. Quality and quantity of antenatal HIV counselling in a PMTCT programme in Mombasa Kenya. AIDS Care. 2006 Apr;18(3):189–93.

Evans C, Ndirangu E. The nursing implications of routine provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in sub-Saharan Africa: a critical review of new policy guidance from WHO/UNAIDS. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009 May 1;46(5):723–31.

Fonchingong CC, Mbuagbo TO, Abong JT. Barriers to counselling support for HIV/AIDS patients in south-western Cameroon. Afr J AIDS Res. 2004 Nov;3(2):157–65.

Sanjana P, Torpey K, Schwarzwalder A, Simumba C, Kasonde P, Nyirenda L, et al. Task-shifting HIV counselling and testing services in Zambia: the role of lay counsellors. Hum Resour Health. 2009 May;30(7):44.

Mwisongo A, Mehlomakhulu V, Mohlabane N, Peltzer K, Mthembu J, Van Rooyen H. Evaluation of the HIV lay counselling and testing profession in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015 Jul;22(15):278.

Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievement of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: a review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013 Sep;17(7):2528–39.

Modula MJ, Ramukumba MM. Nurses’ implementation of mental health screening among HIV infected guidelines. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2018 Jan;1(8):8–13.

Knettel BA, Minja L, Chumba L, Oshosen M, Cichowitz C, Mmbaga BT, et al. Serostatus disclosure among a cohort of HIV-infected pregnant women enrolled in HIV care in Moshi, Tanzania: a mixed-methods study. SSM-Popula Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.11.007.

Ngocho JS, Watt MH, Minja L, Knettel BA, Mmbaga BT, Williams PP, et al. Depression and anxiety among pregnant women living with HIV in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2019 Oct 31;14(10):e0224515.

Sikkema KJ, Mulawa MI, Robertson C, Watt MH, Ciya N, Stein DJ, et al. Improving AIDS care after trauma (ImpACT): pilot outcomes of a coping intervention among HIV-infected women with sexual trauma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):1039–52.

Yehia BR, Stephens-Shield AJ, Momplaisir F, Taylor L, Gross R, Dubé B, et al. Health outcomes of HIV-infected people with mental illness. AIDS Behav. 2015 Aug;19(8):1491–500.

Ncama BP, McInerney PA, Bhengu BR, Corless IB, Wantland DJ, Nicholas PK, et al. Social support and medication adherence in HIV disease in KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa Int J Nurs Stud. 2008 Dec;45(12):1757–63.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the NIH National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Grant R21 AI124344. We also acknowledge support received from the Fogarty International Center (R21 TW011053; D43 TW009595; D43 TW009337), the Duke Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI064518), and the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research (OBSSR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oshosen, M., Knettel, B.A., Knippler, E. et al. “She Just Told Me Not To Cry”: A Qualitative Study of Experiences of HIV Testing and Counseling (HTC) Among Pregnant Women Living with HIV in Tanzania. AIDS Behav 25, 104–112 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02946-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02946-7