Abstract

Innovative combination HIV-prevention and microfinance interventions are needed to address the high incidence of HIV and other STIs among women who use drugs. Project Nova is a cluster-randomized, controlled trial for drug-using female sex workers in two cities in Kazakhstan. The intervention was adapted from prior interventions for women at high risk for HIV and tailored to meet the needs of female sex workers who use injection or noninjection drugs. We describe the development and implementation of the Nova intervention and detail its components: HIV-risk reduction, financial-literacy training, vocational training, and a matched-savings program. We discuss session-attendance rates, barriers to engagement, challenges that arose during the sessions, and the solutions implemented. Our findings show that it is feasible to implement a combination HIV-prevention and microfinance intervention with highly vulnerable women such as these, and to address implementation challenges successfully.

Resumen

Existe la necesidad de una intervención innovadora que combine intervenciones de prevención del VIH y microfinanzas para manejar la alta incidencia de VIH u otras enfermedades de transmisión sexual con mujeres que usan drogas. Nova es un Ensayo Clínico Controlado Aleatorio Grupal para mujeres trabajadoras sexuales que usan drogas en dos ciudades en Kazakstán. La intervención fue adaptada de otras intervenciones anteriores dirigidas a mujeres con alto riesgo de contraer VIH y diseñada para satisfacer las necesidades de las mujeres trabajadoras sexuales que se inyectan o consumen drogas. Este documento describe el desarrollo y la implementación de la intervención Nova. Describimos los componentes de la intervención Nova, los cuales incluyen reducción del riesgo de VIH, entrenamiento en conocimiento financiero, entrenamiento vocacional, y programa de ahorros igualados. También describimos las tasas de asistencia a las sesiones, barreras para la participación, desafíos durante la implementación de las sesiones, y las soluciones implementadas. Los resultados muestran que es posible implementar una combinación de intervención de reducción del riesgo de VIH y micro-finanzas con mujeres altamente vulnerables y resolver problemas para manejar exitosamente los desafíos de la implementación.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Heterosexual transmission of HIV is rapidly outpacing parenteral transmission among women in Kazakhstan; it increased from 47% of new cases in 2006–81% of new cases in 2014 [1]. In 2015, there were approximately 19,100 female sex workers (FSW) in Kazakhstan, with an HIV prevalence of 1.3% [2]. UNAIDS estimates that one in nine cases of HIV in Central Asia occurs among FSW or their paying partners [3, 4], and other studies have suggested that in low- and middle-income countries such as Kazakhstan, FSW have 13.5 times the odds of contracting HIV when compared with all reproductive-age women [5]. And FSW who use drugs, whether injection or noninjection, have a dual risk for HIV [6]. A wide variety of drugs is available in Kazakhstan, including opioids (e.g., heroin, opium, prescription opioids, and synthetic opioids), benzodiazepines, barbiturates, antidepressants, stimulants (e.g., cocaine and methamphetamine), and cannabinoids (both natural and synthetic variants).

The prevalence of HIV among women who both trade sex and use drugs is higher than it is in either group individually; this suggests that the combination of these behaviors heightens the risk of infection [7]. Some women who use drugs report that engaging in sex work enables them to purchase drugs and sustain their drug use. Some women who engage in sex work report using drugs to cope with a lifestyle that is dangerous, traumatic, and highly stigmatizing. Still others may move into and out of engaging in risky sexual and/or drug-use behaviors over the course of their lifetimes to survive ongoing economic and sociocultural disadvantages. The majority of FSW who use drugs in Kazakhstan are street-based, and therefore face extreme poverty, stigma, and gender-based violence, all of which contribute to their HIV risk [3, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, drug use exacerbates poverty and may make women financially dependent on their sex partners, which in turn decreases the women’s ability to negotiate safe injections or safer sex. Use of drugs also increases risk by inhibiting the women’s likelihood of engaging in sexual-risk reduction during sex-work transactions [6, 14].

Given the critical role of these structural factors in shaping risks for HIV infection among FSW who use drugs, HIV-prevention interventions must address risk factors beyond the individual level—for example, through combination HIV-prevention and microfinance interventions that increase women’s access to employment and resources. Microfinance encompasses a range of programs, including financial-literacy education, vocational training, conditional or unconditional cash transfers, formal or informal microcredit or lending, small-business development, and asset-building through savings programs [15,16,17]. Income-generating interventions have been shown to reduce sexual- and drug-risk behaviors among poor women and those engaged in sex work [8, 15, 18, 19]. Creating increased economic opportunity for women may reduce their income from sex work, their drug use, and their high-risk behaviors [20,21,22].

Combination HIV-prevention and microfinance interventions for women who use drugs are limited globally, and absent in Kazakhstan and Central Asia, perhaps due to prevailing assumptions that such women are not capable of engaging in entrepreneurship or sustaining employment [21]. And there have been no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted among women who use drugs in Central Asia. Literature reviews have shown few studies that combine microfinance and HIV prevention for FSW [16, 17, 20], and only one targeting FSW who use drugs [16, 17]. Drug-using FSW who participated in a study of microfinance and HIV-risk reduction in Baltimore, Maryland (US), which provided training in craft-making, showed, on average, a decrease in the number of sexual contacts and of paying partners, and an increase in condom use [21]. FSW who were taught sewing skills in a similar study in India also decreased the number of their paying partners and increased their legal income [22]. Most recently, a savings-led microfinance program, Undarga, among FSW who use alcohol in Mongolia demonstrated efficacy in reducing the number of unprotected sex acts, having a lower percentage of income from sex trading, and increasing the odds that sex work was not their primary source of income [20]. Together, these studies demonstrate that microfinance holds promise for HIV-risk reduction among FSW, though there is a need for more interventions targeting FSW who use drugs.

This paper describes the development and adaptation, content, and implementation of Nova, an innovative combination HIV-prevention and microfinance intervention that incorporates HIV-risk reduction (HIVRR), financial-literacy training (FLT), vocational training (VT), and matched savings. The study was a cluster-randomized controlled trial (c-RCT) designed to test whether women who used drugs and engaged in sex work and were assigned to the HIVRR-and-microfinance (HIVRR + MF) arm would have lower rates of new and/or repeating HIV and STI diagnoses, fewer high-risk sexual and injection-drug-use behaviors, and reduced income from sex work, compared with those assigned to the HIVRR-alone arm.

The study took place in Almaty and Temirtau, two cities in Kazakhstan. Almaty is the former capital and the largest city in Kazakhstan (population 1,703,500), located in the southern part of the country; it is the country’s economic and cultural center. The city is diverse and attracts people from other regions of Kazakhstan and surrounding Central Asian countries. Temirtau (population 181,197) is a smaller, industrial city in northern Kazakhstan, where the country’s first cases of HIV infection were identified [23]. In 2002 the city was home to over half of the registered cases of HIV in Kazakhstan [24].

Full Nova study protocols are described elsewhere [25]; this paper focuses on the process of adapting and implementing the Nova intervention. We also detail session attendance, barriers to attendance and engagement, challenges faced by facilitators during intervention sessions, and solutions implemented in response to these challenges.

Methods

Nova Intervention Design

The Nova intervention consists of a four-session HIV-risk-reduction (HIVRR) component delivered to both study arms of the c-RCT (two sessions per week for 2 weeks), and three microfinance (MF) components delivered only to the treatment arm of the c-RCT: a six-session financial-literacy training (FLT) (three sessions per week for 2 weeks), a 24-session vocational training (VT) (three sessions per week for 8 weeks), and a matched-savings program. Each session in each component lasts approximately 2 h. We employed a two-arm c-RCT study design. The c-RCT compares the treatment arm, which included both HIVRR and MF intervention components, and a control arm, which received the HIVRR intervention alone. In each arm, participants completed the intervention as a “cohort” of six to eight participants.

HIV-Risk-Reduction Component

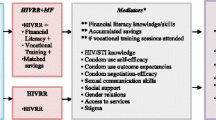

The HIVRR component is guided by both social-cognitive theory (SCT) and a harm-reduction approach [26, 27]. SCT guides many HIV-prevention studies, and the theoretical framework for this intervention (Fig. 1) incorporates many of its social-cognitive mediators. Harm reduction is well accepted as a pragmatic approach to high-risk behaviors if abstinence from the behavior itself is not achievable [28, 29]. The intervention scripts, activities, and goal-setting for Nova’s HIVRR component emphasize that change is incremental, and that any step toward change is desirable and welcomed.

Theoretical Framework. Single asterisk A complete list of moderator, mediator, and outcome measurements is provided elsewhere [22]. Double asterisk Uniquely associated with asset theory and the HIVRR + MF arm

The HIVRR component consists of four sessions lasting 2 h each. Table 1 provides an overview of the session activities, which focus on building participants’ knowledge, awareness, and skills in both sexual and drug-use risk reduction. Participants review information about HIV transmission, identify personal risks for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and discuss how drug use influences sexual risk with both paying and intimate partners. They also review practical skills such as syringe cleaning, emergency-overdose response, and use of male and female condoms. HIVRR emphasizes communication skills with both paying and intimate partners, and role-play activities provide opportunities to practice and to problem-solve overcoming barriers to applying these skills. HIVRR also includes incremental SMART goal setting (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound goals) to build the self-efficacy of the study participants. Participants discuss available informal and formal support systems and learn to identify risks within their social networks. Facilitators connect participants with necessary medical, legal, and social assistance, including referrals to harm-reduction and social programs such as needle and syringe programs, methadone services for women who inject drugs, and shelters for women who are victims of violence. In this context, issues of stigma from service providers are discussed and communication techniques such as reflective listening are suggested as tools to alleviate the challenges of stigma. Participants are encouraged to share experiences of stigmatizing interactions with providers and coping strategies they have used to deal with these situations. Intimate-partner violence (IPV) and gender-based violence (GBV) are of great concern to this population; regular safety-planning check-ins by session facilitators ensure that women receive support.

Participants are compensated the equivalent of US $12 for each session attended, and receive small safe-sex packets with male and female condoms and lubricants.

Microfinance Components

The MF components of Nova draw on SCT and asset theory [30, 31]. Asset theory posits that asset accumulation may yield outcomes ranging from increased economic stability to improvement in household financial circumstances. These, in turn, may mutually reinforce or enhance increases in noneconomic psychological, behavioral, and social assets [30, 31]. For low-income women, assets gained from microfinance programs have included economic, health, gender-based, and psychological empowerment [32, 33]. Asset theory has been successfully applied in both matched-savings and microcredit interventions among poor children and their families in Uganda [34,35,36], sexual-risk reduction among Ugandan adolescents [35, 37], and HIV-risk reduction among women engaged in sex work and poor women in the United States, Kenya, South Africa, and Mongolia [19,20,21, 38].

The MF components are designed to integrate self-efficacy and outcome expectancies related to building financial literacy, vocational training, savings, and matched savings. Each microfinance component builds on the previous one, providing participants in the HIVRR + MF arm with a path to increased economic opportunity. Financial literacy is a critical underpinning of successful economic-empowerment interventions. When such training is provided alongside vocational or business-development training, it leads to improved business knowledge, practices, and revenues [39].

Financial-Literacy Training (FLT)

The purpose of FLT is to provide the knowledge and skills participants need to engage with formal and informal systems of finance. FLT sessions begin after the HIVRR sessions are finished; they consist of six sessions lasting 2 h each. Table 2 provides an overview of the FLT session activities. They focus on knowledge and skills involved in making and managing a budget, accumulating savings, engaging in financial planning, and identifying and problem-solving how to overcome barriers to applying these skills in real life. Participants learn about the local banking system and are encouraged to open savings accounts and begin accumulating savings for matching (described below). Every session includes SMART goal-setting and review; the participants are encouraged to set goals related to banking or savings. Safety-planning check-ins continue in the FLT sessions. Participants are compensated the equivalent of US $12 for each FLT session attended, and continue to receive safe-sex packets.

Vocational Training (VT)

The vocational-training (VT) component of Nova places participants in privately owned, community-based vocational training centers for 2 months (24 sessions) of instruction. Participants choose VT in hairdressing, sewing, or manicure/pedicure services (the last of these only in Almaty). Women attend VT sessions in small groups; other Nova HIVRR + MF participants are their only fellow students. The Nova intervention covers tuition fees as well as compensation (US $12/session) for all sessions attended.

The hairdressing and manicure/pedicure VT includes five to 6 h of theoretical training, in which participants learn professional ethics, communication, hygiene, and personal and client safety, and physiological aspects of skin, nail, and hair care. Practical training (42–43 h) includes skills in techniques, methods, and instruments. In the sewing VT, participants receive 6 h of theoretical training in types of sewing equipment, tools, basic stitches, types of fabrics, and specific ways to work with these fabrics. The training introduces style development and fitting and alteration techniques. Women learn how to construct blouses, skirts, pants, dresses, and jackets.

In Temirtau, Nova partnered with two separate VT centers; in Almaty, Nova contracted with a single training center that provided all three VT options. The institutions selected were privately owned and operated. VT providers were chosen for the quality of their facilities, locations close to the project offices, availability of afternoon and part-time training hours, a reputation for successful student graduation, and subsequent referrals to potential employers.

Matched Savings

The final microfinance component is matched savings to promote asset-building [20, 34, 36]. During the FLT, each participant is encouraged to open a personal savings account at a bank. If she is unable to do so, the participant may open a “Nova account” maintained by the project staff. Participants are expected to deposit some portion of their US $12-per-session attendance compensation into their accounts. Facilitators encourage participants to make at least a small deposit after each session, and to include incremental-savings behaviors in their weekly goals during the FLT.

As participants make deposits into their own savings accounts, the project matches these amounts to encourage continued asset accumulation. The match cap (the maximum amount of individual contributions to be matched by the intervention program) is equivalent to US $60 for FLT sessions and US $250 for 2 months of vocational courses, for a total of US $310. Matches up to US $310 continue until the end of the intervention period. While personal savings are accessible to the participants throughout the MF intervention, the study staff reserves the matched funds until the end of the VT sessions. To maintain matched savings, participants need to attend at least four out of six FLT sessions and 18 out of 24 VT sessions; this ensures that participants have enough intervention exposure to apply basic knowledge and skills. Throughout the sessions, the staff provides participants with weekly account updates, including the amount of matched funds they are eligible for based on their current personal accounts and the maximum they are eligible for based on their session attendance.

After the VT sessions are complete, FLT facilitators lead a transitional session to help participants finalize long-term financial and VT-related goals and determine how to spend personal and matched savings in support of these goals. Matched savings must be spent on equipment, supplies, or additional education related to their chosen vocation to strengthen sustainability. When a participant identifies a goal, half of the price of the equipment, supplies, or continuing education is paid from her personal savings and the remaining half is paid from the matched amount directly to the vendor or educational establishment by the Nova project. Nova requires that participants spend their matched savings within 6 months of their intervention end dates.

Intervention Development and Adaptation

The intervention components described above underwent a thorough adaptation process by the research team in order to ensure cultural congruence and tailoring to the needs of drug-using women engaged in sex work in Kazakhstan. The process included a series of interviews, group discussions, and focus groups. The research team has a long-established collaborative working relationship with Kazakhstan’s Republican AIDS Center, the authority responsible for control, prevention, and treatment of HIV at the national level. For research, study investigators met with representatives of the Republican AIDS Center to present the study, discuss its feasibility, and engage them as active collaborators to ensure their support in providing relevant HIV and STI services for participants. To develop optimal recruitment strategies and adapt the content of the intervention, Nova staffers organized meetings with the epidemiologists, doctors, and outreach workers who engage with sex workers and drug users at the City AIDS Centers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working with high-risk women, and drug-treatment facilities. To prepare the microfinance component of the intervention, staffers held meetings with bank representatives, the Association of Business Women of Kazakhstan, and several providers of vocational courses.

Adaptation of HIVRR and FLT Sessions

The HIVRR component was adapted from three evidence-based HIV interventions: Project WORTH [40], Project Renaissance [41], and Undarga [20]. Project WORTH is a women-specific intervention addressing HIV, partner violence, and access to HIV care. Project Renaissance is designed to reduce HIV and STIs and improve links to care among drug-using couples in Kazakhstan. Undarga is the aforementioned combination HIV-prevention and microfinance intervention tested with FSW who use alcohol in Mongolia. The WORTH intervention activities were used as a base for Nova’s HIVRR intervention manual, and specific activities were added from Undarga and Renaissance. For example, language regarding paying partners and skill-building activities on syringe cleaning and overdose-emergency response were integrated into the intervention. The FLT manual was based on one tested in the Undarga trial, which had previously been adapted from the Global Financial Education Program by Microfinance Opportunities [42] to meet the needs of women engaged in sex work [20, 43]. It was further adapted to accommodate the cultural context of Kazakhstan and the needs of FSW who use drugs. To reduce barriers to attendance, the number of FLT sessions was reduced from 12 to six.

In the adaptation process, experts on HIV research, sex work, and women’s issues provided feedback on the content and the pace of the intervention sessions. This helped ensure that the sessions addressed the needs of FSW who use drugs in the two study sites. For example, the categories of service referrals for participants were expanded, and an emphasis on violence from the police was added to safety-planning discussions. The research team also consulted with staffers at the study’s partner banks to ensure accuracy of the session content on bank accounts, debt, and credit.

A community advisory board (CAB) was convened in each city during intervention development. The members of the CAB included key stakeholders from all areas touched by the intervention, including NGO leaders from community-based facilities (Moi Dom, Shapagat, Doverie), local police representatives from the department tasked with protection from domestic violence, medical personnel from the City AIDS Centers, drug-treatment programs, and other national and international NGOs. Each CAB met once during the formative process and provided valuable feedback that strengthened the intervention content and ensured that it was grounded in the cultural and contextual realities of each community environment. The research team integrated this feedback and refined the intervention sessions and other intervention materials.

Using questions from the Undarga study protocol, a research assistant trained in qualitative research methods conducted a single focus group with five FSW whose socioeconomic and risk-taking status reflected women targeted for inclusion in the intervention. These women were recruited through outreach workers at the City AIDS Center in Karaganda, a larger neighboring city of the Temirtau site. This alternate location was chosen to minimize the possibility of focus-group participants later being recruited to the intervention. Focus-group members provided feedback on the content and process of session delivery, and the team integrated all the feedback and refined the intervention sessions and training protocols.

Vocational Training (VT)

The vocational-training (VT) component was developed specifically for Nova in lieu of the business-development-training component used in the Undarga study. Most Undarga participants found they needed more experience and training before starting a new business, and they used matched savings to attend VT programs to strengthen their skills [20].

To develop the VT component of the study, the team incorporated information from interviews and meetings with HIV experts, local experts on women’s business development, and the focus group with women engaged in sex work in Temirtau and Almaty. Experts on women’s business development recommended offering VT in hairdressing and cooking, and women in the focus groups endorsed these choices. A hairdressing course was piloted with four participants, and barriers and facilitators to participants’ success in these sessions were identified. A VT provider clarified that positive STI or HIV status would prohibit some participants from attending cooking courses. The decision was made to offer sewing classes instead in both Temirtau and in Almaty, and to offer manicure/pedicure classes in Almaty as well.

Intervention Staff Training

Trained female facilitators delivered Nova’s HIVRR and FLT sessions to cohorts of six to eight women. Two facilitators in Almaty and three in Temirtau were trained. All facilitators had prior experience working with female key populations, and most were psychologists. The research team provided sensitivity training to facilitators as well as to VT staff to ensure that the entire project team was prepared for the challenges of working with women who engaged in sex work and used drugs. This training included discussion of stereotypes and stigma and how they affect women’s acceptance in society, employment, and access to healthcare and other services. Vocational teachers also received training in how to teach communication skills to future clients; language choices; professional ethics; and how to maintain self-care and prevent burnout. All facilitators and vocational training staff members completed training in human-subject protection.

Study Recruitment and Enrollment

Women were eligible to enroll in the intervention if they identified as female; were over 18 years old; reported any illicit drug use in the prior 12 months; reported providing sex in return for money, goods, drugs, or services in the prior 90 days; and reported at least one incident of unprotected sex with either a paying or an intimate partner in the prior 90 days. Participants were ineligible if they could not communicate in Russian; intended to move from the study area within the following 12 months; or had a cognitive impairment that would affect their ability to provide consent or participate fully in the intervention activities. More details describing the full study protocol design, including recruitment, eligibility, assessment, and intervention, are available elsewhere [25].

Quality Assurance and Supervision

Study staff conducted regular quality-assurance tests on intervention sessions. Quality-assurance protocols used were those already successfully implemented in other intervention studies by the research team [41, 44, 45]. All HIVRR and MF intervention sessions were audio-recorded. The clinical supervisor reviewed all of the intervention sessions during the initial 6 months of the intervention and a randomly selected 25% of tapes during the remaining months of the study. Session-evaluation forms were completed based on these reviews, and feedback was shared with the facilitator and the study investigators.

Facilitators were provided with ongoing supervision and capacity-building throughout the study period. Kazakhstan-based researchers conducted weekly supervision. The US-based investigators conducted monthly supervision conference calls via Skype (with translation assistance) with all facilitators and study staffers in order to support their skill development and address session-implementation challenges documented in the selected and translated reviews. Supervision also facilitated the development of broader techniques for group management, communication skills, individualized and targeted goal-setting, and self-care for facilitators. Facilitators received coaching on ways to counteract vicarious trauma when events such as suicide or other participant deaths occurred. Finally, supervision addressed emerging issues such as IPV and GBV, participation in sessions under the influence of drugs or alcohol, and strategies to increase comfort in disclosing high-risk sexual and drug-use behaviors.

Results

Study Enrollment and Attendance

Over a 3-year period, the study enrolled 354 women in 53 cohorts. Twenty-seven cohorts were randomized (179 participants) to the HIVRR-only control arm and 26 cohorts (175 participants) to the HIVRR + MF treatment arm. Table 3 provides details about randomization and attendance by study site.

Both study arms had high rates of HIVRR session attendance (an average of 3.5 out of 4 sessions), and 86.7% of randomized participants attended at least three sessions. There were no significant differences in attendance between the two arms. For treatment-arm participants only, the average FLT session attendance was 4.9 out of 6 sessions, and 86.9% of participants attended at least 4 sessions of FLT. For VT, the average session attendance was 19.6 out of 24 sessions, and 80.6% of participants attended at least 18 sessions.

Based on their attendance, 133 (76%) of treatment-arm participants were eligible for the matched-savings component. Eighty-six of these participants (49.1%) deposited money into either a bank or a Nova account. The average deposit amount was 50,048 tenge, the equivalent of US $149.

Barriers to Session Attendance and Engagement

Barriers to session attendance included substance use, transportation expenses, detention by the police, and conflicting or late-night work schedules that prevented attendance at morning sessions. Participants received transportation assistance when necessary—for example, in cases of heavy snowfall, when the study allowed them to be reimbursed for using taxi services to get to the sessions—and sessions were scheduled at times convenient for participants. Similarly, for participants who received HIV-positive test results during express testing, transportation to the City AIDS Center for confirmatory testing was provided. Finally, for participants who needed STI treatment, transportation to the Nova office was provided. Research assistants and facilitators made reminder phone calls to all participants prior to intervention sessions.

Study participants who attended the sessions under the influence of drugs or alcohol presented a significant challenge to facilitators. Because this issue had been anticipated during adaptation, the interventions included activities such as setting ground rules and building participant motivation to attend sessions sober (see Table 1). Participants were also encouraged to make “reduction in substance use” a goal during the goal-setting activities. This issue still came up frequently; an estimated 35% of the participants attended sessions under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The project staff kept a small supply of naloxone in field-office locations in the event of a participant overdose and were trained in naloxone administration.

Participants’ involvement in drug use and sex work made them regular targets of arrest. A representative from the police was included in the CAB at each study site.

Intervention Implementation Challenges

HIVRR Content

Discomfort with Discussing Sexual Behaviors During Intervention Sessions

Some participants were uncomfortable discussing, in their intervention cohorts, sexual behaviors that put them at risk for HIV, while others used very sexually explicit language. It was observed that condom use, sex work, having multiple sexual partners, and having an STI were taboo issues in Kazakhstan culture. This presented a challenge for facilitators, some of whom were also initially uncomfortable with the sexually explicit language used by participants.

Facilitators described divisions among the participants who traded sex formally (i.e., those who considered themselves professional sex workers), and those who did so more informally (i.e., either irregularly or in exchange for drugs or services rather than money). Participants who considered themselves professional sex workers were often stigmatized by those who did not, making group conversation challenging and making participants less open and honest about their risk behaviors. Facilitators addressed this by maintaining a respectful and nonjudgmental group environment, establishing ground rules that validated all participants’ viewpoints, and learning to control the flow of conversation during relevant activities.

Discomfort with Discussing Male-Condom Use with Sexual Partners

Facilitators observed that participants had little knowledge of their intimate partners’ health status. Participants expressed mistrust of their regular partners’ monogamy, yet reported that they rarely used condoms with either regular intimate partners or casual partners. Many participants were afraid to suggest condom use, as this might raise suspicions or jealousy and heighten their risk for IPV. Women were also uncomfortable proposing condom use with casual partners whom they considered “friends.” Although some women said it was appropriate to ask a paying client to use condoms, others said that their regular paying partners would be upset if the women proposed to use condoms because it would indicate a lack of trust. Others reported agreeing to sex without a condom for an additional fee from paying partners. Women learned how to address these high-risk situations using the HIVRR-session communication skills. To reduce the likelihood of increased IPV, facilitators helped women generate solutions to high-risk situations using communication skills and by practicing with coaching and feedback in the group.

Microfinance Components

Facilitators reported several common challenges in the FLT and VT sessions, including balancing savings goals with daily needs, use of the formal banking system, budgeting, and making the transition from vocational training to alternative employment.

Choosing Between Saving or Meeting Daily Needs

Most participants had a strong interest in savings, yet struggled to accumulate savings of their own, as they used their session compensation to meet needs such as food, utility payments, and transportation. Annual expenses, such as school supplies for their children or gifts during the winter holiday season, also conflicted with savings behavior. Many women declined to deposit savings regularly, expecting that they could make up the difference with extra deposits toward the end of the vocational training, yet few women were able to achieve this. Facilitators emphasized the importance of incremental savings and encouraged participants to put aside small amounts of money each week. In supervision sessions, facilitators received booster training in how to encourage incremental savings during the goal-setting activity of the FLT sessions. Some participants slowly overcame the challenges to saving. For example, one participant calculated that simply walking to the intervention sessions instead of using public transportation would allow her to save and deposit an amount large enough to purchase a hair dryer through the matched-savings program. Another woman calculated how much she spent on cigarettes and alcohol, and discussed with her partner the idea of cutting down on these expenses.

A key factor that may have prevented some women from saving was the nationwide recession in Kazakhstan between late 2015 and early 2016. This included a sharp devaluation of the national currency as a result of lower oil prices and inflation, with subsequent stabilization in 2017 [46]. Given the volatile economic situation, many participants may have been discouraged from saving money, instead choosing to purchase tangible goods before the value of their savings decreased further.

Challenges in Using the Formal Banking System

Participants faced several barriers to accessing formal financial institutions. Few participants opened savings accounts in banks; most chose to store their savings in project-based Nova accounts. Facilitators reported that most participants mistrusted financial institutions, and others lacked the required identification cards or citizenship status, or simply did not have enough money to deposit. Many women had received bank loans that they were unable to repay, and they feared being forced to repay these defaulted loans if they tried to open new accounts. Participants were not knowledgeable about the conditions of these past loans, and none had a feasible repayment plan.

Given this unexpected barrier, the research team developed additional protocols for handling and storing participants’ compensation in the Nova accounts. In response to the emerging issue of participant debt, the study added activities in the FLT intervention to address debt and strategies to pay it off. This added language prompted facilitators to use past debt as an example, and encouraged women to consider it in their financial plans and regular goal-setting. Some women visited their banks and negotiated plans to repay their loans. Others chose to improve their current financial situation first in order to create more-stable sources of income to be able to renegotiate loan repayment and use formal banking services.

Challenges in Developing a Budget

The women faced several challenges in developing household budgets. Most participants had very little income and never considered saving money for future spending. For many women without regular income from legal employment, dividing expenses into “regular” and “irregular” subcategories was complicated. Reflecting an issue of self-stigma, women would omit income from sex work, even though this often made up most of their income. Sometimes, with no clear picture of their income, women could make only vague predictions about their future income to build long-term financial plans. Emergencies entailing unexpected expenses for medical needs or the education of children were common. Yet facilitators found that women rarely planned for such emergencies because they needed to spend all their income on day-to-day survival. Participants had to learn how to reduce expenses on drugs, cigarettes, and alcohol, and to prioritize saving goals. According to facilitators, participants incorporated budgeting exercises in their lives in different ways. For example, one participant started to go to the grocery store with a prepared list of items for purchase, which ultimately helped her reduce unnecessary spending.

From Vocational Training to Employment

Nova participants had varying levels of education and of untreated substance use. Because of the often unresolved socioeconomic, health, and other challenges, the range of participants’ VT experiences was broad and their preparedness for transitioning into new vocations varied. Some individuals needed more time than others to gain competence at skills. Having matched savings was helpful to participants transitioning to new vocations. A total of 64 treatment-arm participants (36.6%) used matched savings for vocation-related purchases and 47 participants (26.8%) used their matched savings to purchase more vocational training, such as advanced hairdressing courses. There were also some hairdressing participants who decided to spend their savings on learning manicure/pedicure skills, and vice versa.

As they completed the VT sessions, women reported challenges in transferring to employment the skills they had learned. Women were more likely to find informal, occasional jobs using the skills they had learned rather than full-time employment. There were, however, successful transitions to full-time employment among project participants. Women who had developed strong relationships with their vocational-course teachers were given referrals to private salons. For example, one participant became a manicure/pedicure specialist, successfully worked in a salon, and promoted her services via Instagram. Another participant opened a low-cost hairdressing salon in Almaty.

Challenges Across Conditions

Stigma from Service Providers

Participants reported mixed experiences with stigma from medical and social-service providers due to both their sex work and their drug use. Most participants gave examples of negative interactions they had had with the general medical or social-services system, and many reported that this had prevented them from accessing care. HIV-positive participants reported that trained HIV service providers showed much more compassion and understanding than did general medical providers. At the same time, self-stigma often impeded participants from accessing existing services. Group discussions raised many prejudices that participants held against themselves, including low self-worth. Facilitators addressed this by developing their skills to build social support and to use positive self-talk, both of which helped participants feel confident in accessing services.

Gender-Based Violence

Women who inject drugs and engage in sex trading experience dual risks for violence. Participants described abuse from clients, intimate sexual partners, police, and family members. There are no community-based programs in Kazakhstan to protect women from gender-based violence, and there is limited access to domestic-violence shelters. Some women provided sex services in dangerous locations, such as in clients’ cars or apartments [47, 48]. Safety planning in such situations incorporated strategies such as telling friends where they were or persuading clients to go to an alternative, safer site, and reduced the probability of violence against participants. Facilitators provided leaflets with contact information for the police department responsible for IPV complaints and protection. In one case, a participant asked for protection from an abusive husband. Facilitators referred her to the police service to help her get a formal protection order.

Persistent Unmet Needs of Drug-Using FSW

Intervention facilitators observed that women’s engagement in sex work and drug use made their lives unstable and unsafe, which precluded them from benefiting fully from the program. Many of their basic needs—mental health treatment, drug treatment, personal safety, places to live, legitimate employment—were unmet. Addressing these needs may make a difference in participants being able to set short- and long-term goals and maximize the benefits of intervention participation.

Discussion

The process of implementing the Nova intervention breaks ground for innovative structural interventions addressing the needs of women who face multiple risks for HIV and STIs. Nova is the first c-RCT that combines HIV prevention and microfinance to target women who use drugs in Central Asia and globally. Currently, there are no other RCT studies on combination HIV prevention and microfinance for sex workers who use drugs. Previous microfinance studies among FSW have varying intervention structures and study designs [16,17,18]. While both arms of the c-RCT may receive benefits from psychological, behavioral, and social changes, the HIVRR + MF group includes accumulation of financial knowledge, job skills, and actual monetary assets, as well as additional self-efficacy and empowerment components.

Attendance rates underscore the feasibility and acceptability of delivering this kind of structural intervention to women who inject drugs and engage in sex work. The larger sample size and higher attendance rates improve on those of previously reported microfinance studies [18, 20,21,22]. Women’s ability to attend even the long and intensive vocational-training component supports the idea that vulnerable women can engage actively in a multicomponent, multisession intervention.

Study-team protocols, including using reminder calls, being flexible in response to challenges that arise (e.g., participants’ substance use), and careful support and supervision of facilitators may also have contributed to successful attendance rates. Lessons learned related to each of these issues. They strengthen protocols for future implementation studies using these interventions and may promote successful dissemination of Nova components in the future.

We found that Nova facilitators were flexible in their responses to multiple challenges arising during the intervention, and that regular supervision of facilitators supported this capacity. The challenges identified during implementation provide valuable lessons to those developing new structural interventions, specifically those with microfinance goals. Based on our experience, we believe that future research should focus on how to improve the process of implementing sessions and scripting session activities to ensure the best possible learning experience for participants.

We recommend that even when immersed in local culture, research teams reconsider local cultural norms, taboos, and stigmatized identities to keep open conversations about sex work, sexual language (colloquial as well as academic), and sexual behaviors. Teams should train local service providers in harm-reduction practices and in sensitivity to the needs of highly stigmatized groups such as FSW and women who use drugs. This could be a bidirectional effort, with the research staff sharing lessons learned and best practices with local providers and local providers sharing experience-based practice wisdom with the research staff. Sharing language, experiences, and sensitivity can only strengthen efforts to reduce stigma and promote implementation of research components and related service referrals.

Consistent with other studies, our research found that implementation and sustainability of financial-literacy and savings interventions require partnerships with financial institutions, sometimes including, but also in lieu of, traditional banks [19,20,21,22]. Local banks are often eager to collaborate with programs that may generate a stream of new customers. It is important to negotiate low- or no-fee agreements and to help financial institutions understand the gains to be achieved by engaging longer-term customers. We observed that participants had low trust in financial institutions because of their negative experiences with bank loans. Providing in-house accounts or nontraditional savings options may be important, depending on the participants’ history with loans. Working with banks to integrate microfinance-intervention activities to help participants address existing debt means that participants may eventually be engaged with formal institutions.

Implementing financial-literacy and savings interventions also requires taking into account the current fiscal environment, including fluctuations in currency valuation, in case adjustments must be made to ensure that savings are always a wiser long-term option to increase income compared with immediately spending acquired funds.

We recommend carefully researching and matching vocational options to the interests and capacity of the local target population. And it is critical to provide sensitivity training to vocational trainers, including them as part of the team. This integration of services may strengthen future efforts to implement the program.

To increase the program’s benefits, more access and links to psychiatric and psychological help may be needed to address trauma and mental health issues that might play a role in why women start using drugs and engaging in sex work. Consistent with global studies of women engaged in sex work who use drugs, safety planning was crucial to the intervention [49, 50], especially given the limited access to IPV/GBV services in Kazakhstan. Given the significant proportion of HIV-positive women among this population, a strong component on links to services and adherence to antiretroviral medications may be particularly important in future interventions. Individualized approaches and/or longer vocational-training periods might be tested in future efforts to identify the best combination to achieve successful employment. Future efforts might also take an individual approach rather than a group-based approach. While costly, an individual approach might target the particular needs of women based on their life experiences. Similarly, longer vocational training could ensure enough skill- and capacity-building to help with the transition to jobs using matched savings. This warrants further examination.

Conclusions

There is a critical need for interventions among drug-using FSW to empower them to protect themselves from HIV and STIs, and to access services and care. The structural intervention described here has the potential to contribute to a global effort to achieve the UNAIDS goal of 90-90-90 by 2020, focusing on the needs of one of the groups most vulnerable to HIV infection. The Nova intervention empowers women to reduce their risk for HIV and provides them the option of alternative ways to engage in employment if they choose to reduce or stop sex work. The challenges and potential solutions described in this paper provide critical information to strengthen activities integrated into HIV prevention directed at this group of women, whose day-to-day living environments present complex challenges to any intervention seeking to restructure sources of income. Future efforts should continue to innovate with economic-empowerment approaches, trusting that despite the multiple adversities faced by vulnerable groups, they have the capacity and are motivated to engage with and problem-solve with study teams to develop the skills and knowledge they need to overcome challenges. These approaches and individual activities may be repurposed in other low-resource, high-HIV-prevalence regions with FSW who do or do not use drugs, but also with other vulnerable populations—for example, with transgender women, men who use drugs, or men who have sex with men. Future efforts may examine how best to integrate Nova components into existing HIV services or drug-treatment services to help women reduce the degree to which their safety is dependent on their income. And studies must examine ways to make structural interventions such as Nova sustainable to ensure continued efforts to reduce risk among these most vulnerable groups.

References

Ministry of Healthcare of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Population size estimate of people who inject drugs (PWID) in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Almaty: Republican Center on Prevention and Control of AIDS; 2016.

Ministry of Healthcare of the Republic of Kazakhstan. National report on the AIDS response. Almaty: Republican Center on Prevention and Control of AIDS; 2016.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2010.

UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013.

Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–49.

Baral S, Todd CS, Aumakhan B, Lloyd J, Delegchoimbol A, Sabin K. HIV among female sex workers in the Central Asian Republics, Afghanistan, and Mongolia: contexts and convergence with drug use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:S13–6.

Pinkham S, Malinowska-Sempruch K. Women, harm reduction and HIV. Rep Health Matters. 2008;16(31):168–81.

Stratford D, Mizuno Y, Williams K, Courtenay-Quirk C, O’Leary A. Addressing poverty as risk for disease: recommendations from CDC’s consultation on microenterprise as HIV prevention. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(1):9.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:911–21.

El-Bassel N, Terlikbaeva A, Pinkham S. HIV and women who use drugs: double neglect, double risk. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):312–4.

Rhodes T, Wagner K, Strathdee SA, Shannon K, Davidson P, Bourgois P. Structural violence and structural vulnerability within the risk environment: theoretical and methodological perspectives for a social epidemiology of HIV risk among injection drug users and sex workers. In: Rethinking Soc Epidemiology. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. P. 205–230.

Blankenship KM, Koester S. Criminal law, policing policy, and HIV risk in female street sex workers and injection drug users. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30(4):548–59.

Wechsberg WM, Krupitsky E, Romanova T, et al. Double jeopardy—drug and sex risks among Russian women who inject drugs: initial feasibility and efficacy results of a small randomized controlled trial. Subst Abuse Treat Pr. 2012;7(1):1.

El-Bassel N, Strathdee SA, El Sadr WM. HIV and people who use drugs in central Asia: confronting the perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1):S2–6.

Dworkin SL, Blankenship K. Microfinance and HIV/AIDS prevention: assessing its promise and limitations. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(3):462–9.

Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, O’Reilly KR, Sweat MD. A systematic review of income generation interventions, including microfinance and vocational skills training, for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2014;26(6):659–73.

Arrivillaga M, Salcedo JP. A systematic review of microfinance-based interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2014;26(1):13–27.

Cui RR, Lee R, Thirumurthy H, Muessig KE, Tucker JD. Microenterprise development interventions for sexual risk reduction: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2864–77.

Pronyk PM, Kim JC, Abramsky T, et al. A combined microfinance and training intervention can reduce HIV risk behavior in young female participants. AIDS. 2008;22:1659–65.

Witte SS, Aira T, Tsai LC, et al. Efficacy of a savings-led microfinance intervention to reduce sexual risk for HIV among women engaged in sex work: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):e95–102.

Sherman SG, German D, Cheng Y, Marks M, Bailey-Kloche M. The evaluation of the JEWEL project: an innovative economic enhancement and HIV prevention intervention study targeting drug using women involved in prostitution. AIDS Care. 2006;18(1):1–11.

Sherman SG, Srikrishnan AK, Rivett KA, Liu SH, Solomon S, Celentano DD. Acceptability of a microenterprise intervention among female sex workers in Chennai, India. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):649–57.

Frantz D. Drug use begetting AIDS in Central Asia. New York Times. August 5, 2001.

Buzurukov A. HIV/AIDS epidemic: time is running out for Central Asia. Central Asia/Caucasus Analyst. 2002.

McCrimmon T, Witte S, Mergenova G, et al. Microfinance for women at high risk for HIV in Kazakhstan: study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Trials. 2008;19(1):187.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social and cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman; 1997.

Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K. Update on harm-reduction policy and intervention research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6(1):591–606.

Ti L, Kerr T. The impact of harm reduction on HIV and illicit drug use. Harm Reduct J. 2014;11(1):7.

Sherraden M. Stakeholding: notes on a theory of welfare based on assets. Soc Ser Rev. 1990;64(4):580–601.

Sherraden M. Assets and the poor: a new American welfare policy. New York: M. E. Sharpe; 1991.

Oosterhoff P, Nguyen T, Pham N, Wright P, Hardon A. Can micro-credit empower HIV + women? An exploratory case study in Northern Vietnam. Womens Health Urban Life. 2008;7(1):40–55.

Amin R, Becker S. NGO-promoted microcredit programs and women’s empowerment in rural Bangladesh: quantitative and qualitative evidence. J Dev Areas. 1998;32(2):221–36.

Ssewamala F, Sherraden M. Integrating saving into microenterprise programs for the poor: do institutions matter? Soc Ser Rev. 2004;78(3):404–29.

Ssewamala FM, Chang-Keun H, Neilands T, Ismayilova L, Sperber E. The effect of economic assets on sexual risk taking intentions among orphaned adolescents in Uganda. Am J Public Health Rep. 2010;100(3):483–9.

Ssewamala FM, Chang-Keun H, Neilands T. Asset ownership and health and mental health functioning among AIDS-orphaned adolescents: findings from a randomized clinical trial in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):191–8.

Ssewamala FM, Alicea S, Bannon W, Ismayilova L. A novel economic intervention to reduce HIV risks among school-going AIDS-orphaned children in rural Uganda. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(1):102–4.

Odek WO, Busza J, Morris CN, Cleland J, Ngugi EN, Ferguson AG. Effects of micro-enterprise services on HIV risk behavior among female sex workers in Kenya’s urban slums. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:449–61.

Karlan D, Valdivia M. Teaching entrepreneurship: impact of business training on microfinance clients and institutions. Rev Econ Stat. 2011;93(2):510–27.

El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Goddard-Eckrich D, et al. Efficacy of a group-based multimedia HIV prevention intervention for drug-involved women under community supervision: project worth. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e111528.

El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Terlikbayeva A, et al. Effects of a couple-based intervention to reduce risks for HIV, HCV, and STIs among drug-involved heterosexual couples in Kazakhstan: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(2):196–203.

Opportunities Microfinance. Global financial education program. Washington, DC: Microfinance Opportunities; 2002.

Tsai LC, Witte SS, Aira T, Riedel M, Offringa R, Chang M. Efficacy of a microsavings intervention in increasing income and reducing economic dependence upon sex work among women in Mongolia. Int Soc Work. 2015;61(1):6–22.

El-Bassel N, Jemmott JB, Landis JR, et al. National Institute of Mental Health multisite Eban HIV/STD prevention intervention for African American HIV serodiscordant couples: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1594–601.

El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):963–9.

World Bank. Global economic prospects: weak investments in uncertain times. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank; 2017.

WHO, UNFPA, UNAIDS, NSWP, Bank W, UNDP. Implementing comprehensive HIV/STI programmes with sex workers: practical approaches from collaborative interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Network of Sex Work Projects. Policy brief: impact of criminalization of sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV and violence; 2017.

El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, Chang M. Intimate partner violence and HIV among drug-involved women: contexts linking these two epidemics—challenges and implications for prevention and treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(2–3):295–306.

Weaver TL, Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Resnick HS, Noursi S. Identifying and intervening with substance-using women exposed to intimate partner violence: phenomenology, comorbidities, and integrated approaches within primary care and other agency settings. J Women’s Health. 2015;24(1):51–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants who shared their time and experiences with Project Nova and the project staff who assisted with recruitment, data collection and project implementation. We would like to thank Republican Center on Prevention and Control of AIDS and Dr. Baiserkin, city AIDS center of Almaty, Temirtau and Karaganda for collaboration. We appreciate assistance in recruitment and support of our study participants of NGO “Moi Dom” and “Shapagat” in Temirtau, NGO “Doverie” in Almaty.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Grant No. R01 DA036514, to Drs. Nabila El-Bassel and Susan Witte (Multiple PIs). The funders had no involvement in the design of the study or in collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Columbia University’s IRB and the ethics committee of the Kazakhstan School of Public Health (KSPH), and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mergenova, G., El-Bassel, N., McCrimmon, T. et al. Project Nova: A Combination HIV Prevention and Microfinance Intervention for Women Who Engage in Sex Work and Use Drugs in Kazakhstan. AIDS Behav 23, 1–14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2268-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2268-1