Abstract

People living with HIV are disproportionately affected by food and housing insecurity. We assessed factors associated with experiencing food and/or housing insecurity among women living with HIV (WLHIV) in Canada. In our sample of WLHIV (N = 1403) 65% reported an income less than $20,000 per year. Most (78.69%) participants reported food and/or housing insecurity: 27.16% reported experiencing food insecurity alone, 14.26% reported housing insecurity alone, and 37.28% reported experiencing food and housing insecurity concurrently. In adjusted multivariable logistic regression analyses, experiencing concurrent food and housing insecurity was associated with: lower income, Black ethnicity versus White, province of residence, current injection drug use, lower resilience, HIV-related stigma, and racial discrimination. Findings underscore the urgent need for health professionals to assess for food and housing insecurity, to address the root causes of poverty, and for federal policy to allocate resources to ameliorate economic insecurity for WLHIV in Canada.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Across the globe, experiencing economic insecurity, including inadequate access to money, housing, and food is linked with poor health outcomes [1,2,3,4]. In Canada, people with lower socioeconomic status (SES) are four times more likely to report poor or fair health relative to people with higher SES [5, 6]. A US population-based study (N = 760,000) that examined geocoded census data in two states highlighted how socio-economic disparities account for a significant proportion of health inequities across multiple health outcomes, including AIDS mortality [7].

The concept of syndemics captures the complex dynamic of co-occurring psychosocial and structural factors that shape individual and population level health inequities [8]. Syndemic theory provides a framework for understanding how economic insecurity is linked with co-occurring social and behavioral outcomes that increase vulnerability to HIV, and HIV disease progression among persons living with HIV (PLHIV). Weiser et al’s. [9] conceptual model details nutritional, behavioral and mental health pathways between low SES, food and housing security, individual practices and HIV outcomes. For example, PLHIV may experience loss of income and assets due to illness, in turn compromising food and economic security [9]. Food and housing insecurity have a bidirectional relationship with HIV; food and housing insecurity are risk factors for HIV acquisition and may also contribute to poor HIV-related health outcomes among PLHIV across high, low, and middle-income contexts [10,11,12,13,14].

Food insecurity, an indicator of poverty and low SES, refers to the inability to access nutritionally safe and adequate foods or the uncertainty of being able to access sufficient food in socially acceptable ways [15]. Food insecurity disproportionately impacts PLHIV. A 2005 cross-sectional study found that food insecurity rates were five times higher than the general population national average among PLHIV in Canada [16]. Women living with HIV (WLHIV) may disproportionately experience food insecurity relative to men, for instance, 33% of women in this study were food insecure compared to 20% of men [16]. A 2017 systematic review of seven studies across the globe found that food insecurity is a barrier to antiretroviral therapy adherence among WLHIV [17]. In this review, three studies indicated that WLHIV who experienced food insecurity reported feeling powerless in their relationships as they relied on male partners for food [17]. Gender inequities may increase WLHIV’s vulnerability to poor social and health outcomes associated with food insecurity.

Housing insecurity is multifaceted and includes high costs of housing in relationship to one’s income, poor quality of housing and unstable neighborhoods, living situations that involve overcrowding, and homelessness [18]. Women also experience unique challenges as a result of housing insecurity, including constrained ability to leave contexts of intimate partner violence [19]. The relationship between housing insecurity and HIV is complex. Cross-sectional US studies have revealed that unstable housing and homelessness elevate HIV risk due to higher rates of syringe sharing, condomless sex, and exchanging sex for drugs [12, 13]. Additionally, a 2007 systematic review of 17 studies indicated that housing instability can compromise physical and mental health among PLHIV experiencing homelessness [14]. Similarly, a US cross-sectional study of WLHIV found that unstably housed women reported significantly lower emotional wellness, antiretroviral therapy adherence, environmental safety, physical health and risk reduction practices in comparison with stably housed women [20]. Experiences of housing insecurity result in social exclusion, discrimination, and constrained access to healthcare, food, and shelter—contributing to elevated morbidity and mortality [20, 21]. A longitudinal cohort study with PLHIV (44% female) who use drugs in Vancouver, Canada reported that housing access was associated with increased viral suppression [22]. Housing and food insecurity may present barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence [9]. Integrating poverty reduction strategies into HIV care is integral to advancing health among WLHIV.

Food and housing insecurity often co-occur among PLHIV [23]. Both US and Canadian cross-sectional studies reported that over half of PLHIV who experience housing insecurity also experience food insecurity [24, 25]. A longitudinal study in San Francisco (29% female) reported that severe food insecurity was associated with increased depressive symptoms in homeless and marginally housed PLHIV, and this effect was significantly stronger for women [10]. Concurrent food and housing security may exacerbate HIV treatment and care barriers. Research with PLHIV (41% female) in south Florida found that food and/or housing insecurity was associated with low antiretroviral therapy adherence and deficits in HIV care [26]. Furthermore, studies in Canada and the US reported associations between HIV-related stigma and economic insecurity [27, 28]. The intersection of food and housing insecurity is therefore an urgent area to address among WLHIV.

Despite the frequent co-occurrence of food and housing insecurity, most studies have examined the factors associated with these constructs separately among PLHIV [10, 11, 14, 16, 21,22,23,24, 27,28,29,30,31,32]. A US cross-sectional study with PLHIV [26] (41% female) examined associations between food and housing insecurity and antiretroviral therapy adherence; food and housing insecurity were measured using a single item, precluding an understanding of the separate and combined effects of food and housing insecurity. While there is evidence to suggest that women may be at higher risk of food insecurity [16], and that the impact of food and housing insecurity may have more detrimental consequences for WLHIV [9, 10], previous studies on food and housing insecurity and HIV have had majority male samples [10, 16, 22, 24, 26, 32]. Examining food and housing insecurity among WLHIV can inform gender-sensitive policy and practice to advance WLWH’s health and wellbeing in Canada, with implications for other contexts.

We examined factors associated with separate and concurrent experiences of food and housing insecurity among WLHIV. This approach is informed by syndemics frameworks that explore the intersection of HIV infection [33], stigma [34, 35], substance abuse, and poverty [36]. Our study aims to explore factors associated with separate and concurrent experiences of food and housing insecurity among WLHIV enrolled in a national Canadian study.

Methods

Data were derived from a cross-sectional survey with 1424 WLHIV who completed a baseline visit between August 2013 and May 2015 for the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual & Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS), a large, longitudinal, national, community-based research (CBR) study in British Columbia (BC), Ontario, and Quebec, Canada. CHIWOS focuses on healthcare utilization, healthcare access, and health outcomes among WLHIV in Canada. A description of the cohort and CBR approach of CHIWOS have been detailed elsewhere [37, 38]. Peer research associates (PRAs)—WLHIV trained and supported as researchers—helped to recruit self-identified WLHIV aged 16 years or older using non-random sampling methods such as word-of-mouth through PRA networks and online through Listservs for WLHIV and the study website, Facebook page, and Twitter. PRAs also engaged in venue-based sampling, recruiting participants from AIDS service organizations, HIV health clinics, and community-based organizations serving WLHIV, particularly serving those populations who are overrepresented in the Canadian HIV epidemic (e.g., women who use drugs) [37,38,39].

PRAs administered a structured online questionnaire (median completion time 89 min [IQR 71, 115]) to participants in a confidential setting of the participant’s choice. Some participants in rural or remote areas completed the questionnaire via phone or Skype [37, 38]. Participants received a $50 honorarium for their participation. Ethics approval was obtained from research ethics boards at Women’s College Hospital, University of Toronto (Ontario), Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia/Providence Health (British Columbia), and McGill University Health Centre (Quebec). Study sites with independent Research Ethics Boards obtained their own approval prior to commencing enrolment.

Measures

Housing insecurity was assessed with the questions: (1) “Which of the following best describes the residence in which you currently live?” (house that you own, apartment or condominium that you own, house that you rent, floor in a house that you rent, a basement apartment that you rent, apartment or condominium that you rent, self-contained room in a house with other people, self-contained room in an apartment with other people, self-contained room with amenities, self-contained room with no amenities, a HIV care group home, a housing facility, outdoors/on the street/parks/in a car, couch surfing, transition house/halfway house/safe house, shelter, jail) and (2) “Given your total household income, how difficult is it to meet your monthly housing costs including rent/mortgage, property taxes, and utilities (e.g., heat, electricity, water and gas)?” Insecure housing was coded as 1 if participants reported single room occupancy living with or without amenities (but not in a house or apartment with other people); a transition house, halfway house, or safe house; couch surfing; other/outdoors on street, parks, or in a car, or if participants responded that it was “fairly difficult” or “very difficult” to meet monthly housing costs regardless of the type of housing. Previous research has used a single-item measure of ability to meet monthly housing costs to determine housing insecurity [27]. In addition, a qualitative study on developing a measure of housing insecurity found that two important indicators of housing insecurity are housing type and subjective assessments of housing stability [40]. Secure housing was coded as 0, if participants reported living in an apartment (own or rent), house (own or rent), or a self-contained room in an apartment, house, or group home; and if participants responded that it was “Not at all difficult” or “A little difficult” to meet monthly housing costs.

Food insecurity was assessed using an adapted version of the validated Canadian Community Health Survey Household Food Security Survey Module [41]. Three statements were used, with response options of ‘Often True (2), ‘Sometimes True (1)’, or ‘Never True (0)’. The sum of these three items ranges from 0 to 6. A score of 0–1 was coded as food secure (0) and 2–6 was coded as food insecure (1). Items were: “In the past 12 months, you and other household members worried that food would run out before you got money to buy more”, “In the past 12 months, the food that you and other household members bought just didn’t last, and there wasn’t any money to get more”, “In the past 12 months, you and other household members couldn’t afford to eat balanced meals.”

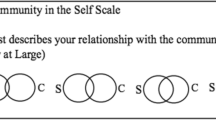

Experiencing food and housing insecurity concurrently was measured by dividing participants into four exhaustive, mutually exclusive groups. Participants who reported never experiencing any housing insecurity or food insecurity were coded as 0 (no food/housing insecurity), those who reported only food insecurity but no housing insecurity were coded as 1 (food insecurity only), those who reported only housing insecurity but no food insecurity were coded as 2 (housing insecurity only), and those who reported both food insecurity and housing insecurity were coded as 3 (concurrent food and housing insecurity).

Informed by ‘Social Ecological’ [42] and ‘Stigma and HIV Disparities’ [43] theoretical models, we examined intrapersonal (injection drug use, resilience) and social and structural (social support, HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination) level variables associated with food and housing insecurity. Injection drug use was derived with two questions: “In your lifetime, have you ever used injection drugs?” Participants who responded “Yes” were asked: “Over the last three months, have you used injection drugs?” Participant who responded “No” to the first question were coded as never IDU (0), those who responded “Yes” to the first question but “No” to the second question were coded previous IDU, not currently (1), and those who responded “Yes” to both questions were coded as current IDU (2). Resiliency was assessed using the Resiliency Scale (RS-10) to measure personal competence and self-acceptance. The scale ranges from 18 to 70 (Cronbach α = 0.91) with higher scores indicating higher resilience [44, 45].

Social and structural factors included HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, and social support. HIV-related stigma was measured with the HIV Stigma Scale (HSS) (Cronbach α = 0.85, range 0–100) [46,47,48]. Racial discrimination was assessed with the Everyday Discrimination Scale-Racism (EDD-R) (Cronbach α = 0.95, range 8–48) [49, 50]. Gender discrimination was measured with the Everyday Discrimination Scale-Sexism (EDD-S) (Cronbach α = 0.94, range 8–48) [49]. Social support was assessed with the four-item Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS-SSS) (Cronbach α = 0.85, range 4–20) [51, 52].

Covariates include a range of potential sociodemographic variables considered in this study, including age (continuous), gender identity (cisgender, transgender, other gender), legal relationship status (married, common law, single, separated, divorced, widowed and other), ethnicity (Indigenous, African, Caribbean or Black, White and other ethnicities), education (less than high school, high school or above), number of financial dependents (continuous), Canadian income poverty level (< $20,000 household annual income and ≥ $20,000 household annual income), year of HIV diagnosis (continuous), and province of residence (BC, Ontario or Quebec).

Statistical Analyses

We first conducted descriptive analyses of all variables for the whole sample. Bivariate analysis using ANOVA or Chi square were conducted to identify differences by experience of food and/or housing insecurity. Univariate and multivariable multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine the appropriate estimates of the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for food insecurity only, housing insecurity only, and concurrent food and housing insecurity, with no experience of economic insecurity as the reference group, controlling for socio-demographic variables. Backward stepwise selection method was used to determine the final model. A goodness of fit test adopting Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was conducted to determine the performance of the model. Statistical significance was set at the p < 0.05 level. Participants who answered “Don’t know” or “Prefer not to answer” to either of the questions listed above regarding economy insecurity were excluded from the analysis (N = 21). Missing responses were excluded from the analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 14.0).

Results

A total of 1403 participants with complete food and housing insecurity information were included in analyses. One-fifth (N = 299, 21.31%) reported no food or housing insecurity, one-quarter (N = 381, 27.16%) reported food insecurity alone, 14.26% (N = 200) reported housing insecurity alone, and 37.28% (N = 523) reported concurrent food and housing insecurity. Table 1 reports socio-demographic characteristics for the whole sample.

Table 2 demonstrates the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio for food and housing insecurity among WLHIV in Canada. The base outcome group selected for the regression models were participants that reported no food or housing insecurity. The AIC for the final model was 2.30, which suggests a good model fit.

Socio-demographic factors were associated with food and housing insecurity. In adjusted analyses, less than $20,000 CAD household annual income was associated with food insecurity alone, housing insecurity alone, and combined food and housing insecurity (AOR 8.04, 95% CI 5.44–11.87, p < 0.001, AOR 2.11, 95% CI 1.37–3.23, p < 0.01, AOR 6.65, 95% CI 4.61–9.60, p < 0.001). African, Caribbean or Black versus White ethnicity was associated with food insecurity alone, housing insecurity alone, and combined food and housing insecurity (AOR 2.11, 95% CI 1.27–3.49, p < 0.01, AOR 2.11, 95% CI 1.20–3.70, p < 0.01, AOR 2.81, 95% CI 1.73–4.57, p < 0.001). Indigenous participants were more likely to report food insecurity than White participants (AOR 1.73, 95% CI 1.01–2.95, p < 0.05). Province of residence was also associated with food and housing insecurity. Residing in Ontario versus BC was associated with food insecurity (AOR 2.50, 95% CI 1.54–4.05, p < 0.001). Residing in Quebec versus BC was associated with increased odds of food insecurity, housing insecurity, and combined food and housing insecurity (AOR 10.20, 95% CI 5.54–18.78, p < 0.001, AOR 6.51, 95% CI 3.48–12.19, p < 0.001, AOR 2.40, 95% CI 1.33–4.32, p < 0.01).

Intrapersonal variables of injection drug use and resilience were associated with food and housing insecurity. In adjusted analyses, compared to the odds of experiencing no food/housing insecurity, participants who were currently injecting drugs were more likely to experience concurrent food and housing insecurity than those who had never injected drugs (AOR 3.28, 95% CI 1.48–7.28, p < 0.001). Participants who reported lower resilience scores were more likely to experience food insecurity and concurrent food and housing insecurity (AOR 0.97, 95% CI 0.95–0.99, p < 0.05, AOR 0.97, 95% CI 0.95–0.99, p < 0.01).

HIV-related stigma was associated with higher odds of experiencing food insecurity only and concurrent food and housing insecurity (AOR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.02, p < 0.05, AOR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01–1.02, p < 0.01), compared to no experiences of food/housing insecurity. Similarly, racial discrimination was associated with increased odds of experiencing food insecurity alone and concurrent food and housing insecurity (AOR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.06, p < 0.001, AOR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.07, p < 0.001).

Discussion

We found that the overwhelming majority (79%) of WLHIV in Canada experienced food insecurity, housing insecurity, or concurrent food and housing insecurity. This is striking compared to prevalence in the general population; an estimated 9% of the Canadian population being homeless [53] or unstably housed [54] and 11% experiencing food insecurity [55]. In the present study, food and housing insecurity were independently associated with marginalized identities (e.g., Indigenous and Black vs. White ethnicity), social inequities (e.g., HIV-related stigma), and current substance use. These findings indicate the urgent need to address food and housing insecurity among WLHIV in policy, practice and community-based settings to ensure WLHIV can realize optimal health and wellbeing.

Our finding of racial disparities in food and housing insecurity corroborates previous Canadian and US research that indicates increased odds of food and housing insecurity among Indigenous and Black populations [16, 26]. WLHIV experiencing food and housing insecurity were more likely to report racial discrimination and HIV-related stigma. This substantiates Weiser et al’s. [9] conceptual framework that links food insecurity, discrimination, and social exclusion in WLHIV [9]. HIV-related stigma and racial discrimination can compromise access to health care and social support [56], which may further exacerbate physical and mental health inequities in WLHIV. Future research could further examine the mechanisms by which HIV-related stigma and racial discrimination are associated with food and housing insecurity in order to inform stigma reduction initiatives. For instance, if racial discrimination in housing is an issue for WLHIV, this has policy and advocacy implications for the housing sector. Research has documented racial discrimination in Canada’s housing market [57], and strategies to address this are urgently needed for Black and Indigenous WLHIV. Lifetime racial discrimination, particularly in employment and education, is associated with severe food insecurity in African American households [58]. As employment and education are two major avenues to reduce food insecurity [59], and racial discrimination impedes hiring, pay level, and educational quality and achievement [60, 61], racial discrimination likely has downstream impacts on food insecurity. Additionally, a recent report on Indigenous peoples’ health in Toronto, Canada indicated that 26% of Indigenous adults reported household food insecurity [62]. Among Indigenous peoples, food insecurity is associated with historical and current colonial policies such as forced relocation and control of food provisions in Indigenous communities that reduce access to, and consumption of, traditional foods [63, 64].

Current injection drug use was associated with food and housing insecurity. This aligns with prior research that highlighted linkages between non-prescribed drug use and homelessness among women [65], and between injection drug use and food insecurity among PLHIV [11, 29]. Moreover, WLHIV who use non-prescribed drugs report significantly lower health-related quality of life, and drug use may be a way of coping with poor mental health [66]. In contexts of poverty, WLHIV are faced with the complexity of navigating competing survival needs, and substance use may be a central coping resource that takes precedence over food and shelter [67]. The interplay between injection drug use and housing and food insecurity requires further investigation. It is plausible that there are also bidirectional relationships between food and housing insecurity and injection drug use. For example, unsheltered women have higher odds of using non-prescribed drugs than their sheltered counterparts [68]. Longitudinal studies can further explore the pathways between injection drug use, food and housing insecurity to design appropriate interventions for WLHIV who inject drugs.

There are study limitations. The purposive sampling limits generalizability, and we primarily included participants who currently accessed HIV services. Thus, we may have oversampled participants connected to care who may be more likely to experience poverty and stigma. On the other hand, we may have excluded participants who were more marginalized and not accessing HIV care. Future research should use random sampling to enhance generalizability of findings to other WLHIV. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study findings precludes understanding causation or temporal changes between food/housing insecurity and other variables. Longitudinal approaches can better clarify these associations [69]. Longitudinal approaches also help to elucidate if food and housing insecurity did, in fact, have unique and combined effects or if findings may have been influenced by the large sample size and inclusion of covariates. Third, a previous study on housing instability and HIV risk in women used five separate housing indicators [70]. Our brief housing insecurity measure may have missed indicators associated with social and health disparities. Future studies on WLHIV should include more subjective measures of housing insecurity in order to capture the precarious nature of housing for women who may rely on their partners for shelter [19].

Despite these limitations our study is unique in exploring factors associated with the separate and concurrent experiences of food and housing insecurity among WLHIV. Our findings align with the Multi-Dimensional Poverty Index that examines multiple, interlocking forms of poverty to distinguish and target the persons experiencing the most poverty for interventions [71]. This multi-dimensional versus unidimensional approach to poverty examines across indicators to gather more information about the incidence and intensity of poverty [72]. The intensity of poverty—how many indicators in which people experience deprivation—matters [73]. Examining levels of poverty can inform poverty alleviation strategies targeting WLWH; tackling housing or food insecurity alone may not be sufficient for WLHIV who experience concurrent food and housing insecurity [8]. We contribute to the nascent intersectional stigma literature [74] to demonstrate the importance of examining—and addressing—both HIV-related stigma and racial discrimination in efforts to address multi-dimensional poverty among WLHIV.

Our findings have significant implications for practice, policy and research. Our study revealed alarming rates of food and housing insecurity among WLHIV in Canada, highlighting the urgent need for policy focusing on poverty reduction that addresses the root causes of economic insecurity. Health care providers who work with PLHIV should screen patients for stable housing and access to adequate food in order to provide holistic healthcare and referrals to resources to address the basic needs of patients [14]. These referrals can guide patients to advocates and resources to secure housing, food supplements, legal and civil rights [67]. For instance, a program called “maximally assisted therapy” for unstably housed PLHIV with a history of addiction or mental health challenges in Vancouver, Canada increased the likelihood of 95% antiretroviral therapy adherence 5-fold in comparison with a control group [75].

Black and Indigenous women, and those reporting higher HIV-related stigma and racial discrimination, were more likely to experience economic insecurity. This highlights the need for intersectional approaches to practice and research that address multiple, co-occurring forms of social marginalization [74, 76]; there are evidence-based approaches to reduce HIV-related stigma [77, 78] but less knowledge on how to address the intersection of HIV-related stigma and racial discrimination [74, 79]. A US based study suggested the potential role of social capital development as a housing intervention after finding that lower social capital and discrimination were associated with housing instability among African American adults [80]. Developing social capital in homelessness prevention interventions for WLHIV warrants further attention.

Conclusion

Interventions to tackle the syndemics of social and economic inequities can integrate social and structural contexts to advance the wellbeing of WLHIV [81]. Multi-dimensional approaches to poverty that assess and address concurrent housing and food insecurity hold promise in reaching the most marginalized [82]. Poverty reduction strategies are urgently needed to examine social policies that may in fact contribute to entrenched poverty. For example, the need to enroll in social assistance to receive antiretroviral therapy coverage in some provinces limits the opportunity for securing employment and keeps many PLHIV living below the poverty line [83]. At the national level, policies and resources are required for food assistance and housing programs for WLHIV in order to increase access to regular HIV medical care. While many WLHIV in Canada receive social assistance, which can include a housing subsidy, current policies do not consider access to food [84]. Enhanced understanding of how socio-environmental stressors interact to shape health and wellbeing can inform strategies to promote health equity and human rights among WLHIV [26].

References

Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, Schaap MM, Menvielle G, Leinsalu M, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2468–81.

Bambra C, Netuveli G, Eikemo TA. Welfare state regime life courses: the development of western European welfare state regimes and age-related patterns of educational inequalities in self-reported health. Int J Health Serv. 2010;40(3):399–420.

Aldabe B, Anderson R, Lyly-Yrianainen M, Parent-Thirion A, Vermeylen G, Kelleher CC, et al. Contribution of material, occupational, and psychosocial factors in the explanation of social inequalities in health in 28 countries in Europe. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(12):1123–31.

Auger N, Alix C. Income, income distribution and health in Canada. In: Raphael D, editor. Social determinants of health: Canadian perspectives. 2nd ed. Toronto: Canadian Scholar’s Press; 2009. p. 61–74.

James PD, Wilkins R, Detsky AS, Tugwell P, Manuel DG. Avoidable mortality by neighbourhood income in Canada: 25 years after the establishment of universal health insurance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(4):287–96.

Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, Mustard C, Choinière R. The Canadian census mortality follow-up study, 1991 through 2001. Health Rep. 2008;19(3):25.

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Painting a truer picture of US socioeconomic and racial/ethnic health inequalities: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):312–23.

Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17(4):423–41.

Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, Kushel MB, Tsai AC, Tien PC, et al. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1729S–39S.

Palar K, Kushel M, Frongillo EA, Riley ED, Grede N, Bangsberg D, et al. Food insecurity is longitudinally associated with depressive symptoms among homeless and marginally-housed individuals living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1527–34.

Palar K, Laraia B, Tsai AC, Johnson MO, Weiser SD. Food insecurity is associated with HIV, sexually transmitted infections and drug use among men in the United States. AIDS. 2016;30(9):1457–65.

Neaigus A, Reilly KH, Jenness SM, Hagan H, Wendel T, Gelpi-Acosta C. Dual HIV risk: receptive syringe sharing and unprotected sex among HIV-negative injection drug users in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2501–9.

Deering KN, Rusch M, Amram O, Chettiar J, Nguyen P, Feng CX, et al. Piloting a ‘spatial isolation’ index: the built environment and sexual and drug use risks to sex workers. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):533–42.

Leaver CA, Bargh G, Dunn JR, Hwang SW. The effects of housing status on health-related outcomes in people living with HIV: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):85–100.

Anderson SA. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J Nutr (USA). 1990. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1555.

Normén L, Chan K, Braitstein P, Anema A, Bondy G, Montaner JS, et al. Food insecurity and hunger are prevalent among HIV-positive individuals in British Columbia, Canada. J Nutr. 2005;135(4):820–5.

Chop E, Duggaraju A, Malley A, Burke V, Caldas S, Yeh PT, et al. Food insecurity, sexual risk behavior, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among women living with HIV: a systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1337774.

Johnson A, Meckstroth A. Ancillary services to support welfare to work. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998.

Thurston WE, Roy A, Clow B, Este D, Gordey T, Haworth-Brockman M, et al. Pathways into and out of homelessness: domestic violence and housing security for immigrant women. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2013;11(3):278–98.

Delavega E, Lennon-Dearing R. Differences in housing, health, and well-being among HIV-positive women living in poverty. Soc Work Public Health. 2015;30(3):294–311.

Bowen EA. A multilevel ecological model of HIV risk for people who are homeless or unstably housed and who use drugs in the urban United States. Soc Work Public Health. 2016;31(4):264–75.

Marshall BD, Elston B, Dobrer S, Parashar S, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, et al. The population impact of eliminating homelessness on HIV viral suppression among people who use drugs. AIDS. 2016;30(6):933–42.

Parpouchi M, Moniruzzaman A, Russolillo A, Somers JM. Food insecurity among homeless adults with mental illness. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159334.

Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles S, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Frongillo EA. Food insecurity among homeless and marginally housed individuals living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):841–8.

Anema A, Weiser SD, Fernandes KA, Ding E, Brandson EK, Palmer A, et al. High prevalence of food insecurity among HIV-infected individuals receiving HAART in a resource-rich setting. AIDS Care. 2011;23(2):221–30.

Surratt HL, O’Grady CL, Levi-Minzi MA, Kurtz SP. Medication adherence challenges among HIV positive substance abusers: the role of food and housing insecurity. AIDS Care. 2015;27(3):307–14.

Logie CH, Jenkinson JI, Earnshaw V, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, housing insecurity and wellbeing among African and Caribbean black women living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0162826.

Wolitski RJ, Pals SL, Kidder DP, Courtenay-Quirk C, Holtgrave DR. The effects of HIV stigma on health, disclosure of HIV status, and risk behavior of homeless and unstably housed persons living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1222–32.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Milloy M, Anema A, Zhang R, Montaner JS, et al. Severe food insecurity is associated with elevated unprotected sex among HIV-seropositive injection drug users independent of HAART use. AIDS (Lond, Engl). 2011;25(16):2037.

Whittle HJ, Palar K, Napoles T, Hufstedler LL, Ching I, Hecht FM, et al. Experiences with food insecurity and risky sex among low-income people living with HIV/AIDS in a resource-rich setting. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.18.1.20293.

Milloy M-J, Kerr T, Bangsberg DR, Buxton J, Parashar S, Guillemi S, et al. Homelessness as a structural barrier to effective antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive illicit drug users in a Canadian setting. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(1):60–7.

Vogenthaler NS, Hadley C, Lewis SJ, Rodriguez AE, Metsch LR, del Rio C. Food insufficiency among HIV-infected crack-cocaine users in Atlanta and Miami. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(9):1478–84.

Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–42.

Mustanski B, Andrews R, Herrick A, Stall R, Schnarrs PW. A syndemic of psychosocial health disparities and associations with risk for attempting suicide among young sexual minority men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):287–94.

Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Poteat T, Wagner AC. Syndemic factors mediate the relationship between sexual stigma and depression among sexual minority women and gender minorities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(5):592–9.

Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(7):991–1006.

Loutfy M, de Pokomandy A, Kennedy VL, Carter A, O’Brien N, Proulx-Boucher K, et al. Cohort profile: The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS). PLoS ONE. 2017;12(9):e0184708.

Loutfy M, Greene S, Kennedy VL, Lewis J, Thomas-Pavanel J, Conway T, et al. Establishing the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS): operationalizing community-based research in a large national quantitative study. BMC Health Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0190-7.

Webster K, Carter A, Proulx-Boucher K, Dubuc D, Nicholson V, Beaver K, et al. Strategies for recruiting women living with HIV in community-based research: lessons from Canada. Prog Community Health Partnersh Res Educ Action. 2018;12(1):21–34.

Frederick TJ, Chwalek M, Hughes J, Karabanow J, Kidd S. How stable is stable? Defining and measuring housing stability. J Community Psychol. 2014;42(8):964–79.

Béland Y. Canadian community health survey—methodological overview. Health Rep. 2002;13(3):9.

Baral S, Logie C, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2011;13:482.

Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225.

Wagnild GM. The resilience scale user’s guide: for the US English version of the resilience scale and the 14-item resilience scale (RS-14). Worden: Resilience Centre; 2011.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):518–29.

Palmer AK, Duncan KC, Ayalew B, Zhang W, Tzemis D, Lima V, et al. “The way I see it”: the effect of stigma and depression on self-perceived body image among HIV-positive individuals on treatment in British Columbia, Canada. AIDS Care. 2011;23(11):1456–66.

Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam P, Templin T, Frey M. Stigma scale revised: reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV+ youth. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(1):96–8.

Williams DR, Yan Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51.

Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1576–96.

Stewart AL. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham: Duke University Press; 1992.

Gjesfjeld CD, Greeno CG, Kim KH. A confirmatory factor analysis of an abbreviated social support instrument: the MOS-SSS. Res Soc Work Pract. 2008;18(3):231–7.

Gaetz S, Dej E, Richter T, Redman M. The state of homelessness in Canada 2016. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press; 2016.

Statistics Canada. Homeownership and shelter costs in Canada. Government of Canada 2011. Updated 2016/9/15. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-014-x/99-014-x2011002-eng.cfm.

Research PFIP. Food insecurity in Canada 2012. Updated 2017. http://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/.

Phelan JC, Lucas JW, Ridgeway CL, Taylor CJ. Stigma, status, and population health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:15–23.

Dion KL. Immigrants’ perceptions of housing discrimination in Toronto: the Housing New Canadians project. J Soc Issues. 2001;57(3):523–39.

Burke MP, Jones SJ, Frongillo EA, Fram MS, Blake CE, Freedman DA. Severity of household food insecurity and lifetime racial discrimination among African-American households in South Carolina. Ethn Health. 2018;23(3):276–92.

Gundersen C, Kreider B, Pepper J. The economics of food insecurity in the United States. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2011;33(3):281–303.

The Annie E. Kasey Foundation. Race for results: building a path to opportunity for all children. 2014.

Pager D, Shepherd H. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:181–209.

Toronto Seventh Generation Midwives. Our Health Counts: a community health assessment for the people, by the people. Well Living House; 2018.

Daschuk JW. Clearing the plains: disease, politics of starvation, and the loss of Aboriginal life. Regina: University of Regina Press; 2013.

Rudolph KR, McLachlan SM. Seeking Indigenous food sovereignty: origins of and responses to the food crisis in northern Manitoba, Canada. Local Environ. 2013;18(9):1079–98.

Lum PJ, Sears C, Guydish J. Injection risk behavior among women syringe exchangers in San Francisco. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(11):1681–96.

Riley ED, Wu AW, Perry S, Clark RA, Moss AR, Crane J, et al. Depression and drug use impact health status among marginally housed HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17(8):401–6.

Riley E, Gandhi M, Bradley Hare C, Cohen J, Hwang S. Poverty, unstable housing, and HIV infection among women living in the United States. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):181–6.

Nyamathi AM, Leake B, Gelberg L. Sheltered versus nonsheltered homeless women. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(8):565–72.

Anema A, Vogenthaler N, Frongillo EA, Kadiyala S, Weiser SD. Food insecurity and HIV/AIDS: current knowledge, gaps, and research priorities. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009;6(4):224–31.

Weir BW, Bard RS, O’Brien K, Casciato CJ, Stark MJ. Uncovering patterns of HIV risk through multiple housing measures. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):31–44.

Alkire S, Santos ME. Acute multidimensional poverty: a new index for developing countries. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative; 2010.

Alkire S, Foster J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measures. Working Paper 7. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI); 2007.

Alkire S, Conconi A, Seth S. Multidimensional Poverty Index 2014: Brief methodological note and results. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. 2014.

Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):863–9.

Parashar S, Palmer AK, O’Brien N, Chan K, Shen A, Coulter S, et al. Sticking to it: the effect of maximally assisted therapy on antiretroviral treatment adherence among individuals living with HIV who are unstably housed. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1612–22.

Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001124.

Nyblade L, Stangl A, Weiss E, Ashburn K. Combating HIV stigma in health care settings: What works? J Int AIDS Soc. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2652-12-15.

Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(Suppl 2):18637.

Loutfy M, Tharao W, Logie C, Aden MA, Chambers LA, Wu W, et al. Systematic review of stigma reducing interventions for African/Black diasporic women. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:19835.

Priester MA, Foster KA, Shaw TC. Are discrimination and social capital related to housing instability? Hous Policy Debate. 2017;27(1):120–36.

Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):941–50.

Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, Gogolishvili D, Globerman J, Rueda S, et al. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):e1–23.

Rueda S, Chambers L, Wilson M, Mustard C, Rourke SB, Bayoumi A, et al. Association of returning to work with better health in working-aged adults: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):541–56.

Government of Canada. Social assistance statistical report: 2009–2013. 2013.

Acknowledgements

The CHIWOS Research Team would like to thank women living with HIV for their contributions to this study. We also thank the National Team of Co-investigators, Collaborators, and Peer Research Associates and acknowledge the National Steering Committee, our three Provincial Community Advisory Boards, the National CHIWOS Aboriginal Advisory Board, the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS for data support and analysis, and all our partnering organizations for supporting the study. Listed here are all research team members and affiliated institutions; all those not listed by name on the title page are to be hyperlinked as authors: The CHIWOS Research Team: British Columbia: Aranka Anema (University of British Columbia), Denise Becker (Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Lori Brotto (University of British Columbia), Allison Carter (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Simon Fraser University), Claudette Cardinal (Simon Fraser University), Guillaume Colley (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Erin Ding (British Columbia Centre for Excellence), Janice Duddy (Pacific AIDS Network), Nada Gataric (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Robert S. Hogg (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and Simon Fraser University), Terry Howard (Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Shahab Jabbari (British Columbia Centre for Excellence), Evin Jones (Pacific AIDS Network), Mary Kestler (Oak Tree Clinic, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre), Andrea Langlois (Pacific AIDS Network), Viviane Lima (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Elisa Lloyd-Smith (Providence Health Care), Melissa Medjuck (Positive Women’s Network), Cari Miller (Simon Fraser University), Deborah Money (Women’s Health Research Institute), Valerie Nicholson (Simon Fraser University), Gina Ogilvie (British Columbia Centre for Disease Control), Sophie Patterson (Simon Fraser University), Neora Pick (Oak Tree Clinic, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre), Eric Roth (University of Victoria), Kate Salters (Simon Fraser University), Margarite Sanchez (ViVA, Positive Living Society of British Columbia), Jacquie Sas (CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network), Paul Sereda (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS), Marcie Summers (Positive Women’s Network), Christina Tom (Simon Fraser University, BC), Lu Wang (British Columbia Centre for Excellence), Kath Webster (Simon Fraser University), Wendy Zhang (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS). Ontario: Rahma Abdul-Noor (Women’s College Research Institute), Jonathan Angel (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute), Fatimatou Barry (Women’s College Research Institute), Greta Bauer (University of Western Ontario), Kerrigan Beaver (Women’s College Research Institute), Anita Benoit (Women’s College Research Institute), Breklyn Bertozzi (Women’s College Research Institute), Sheila Borton (Women’s College Research Institute), Tammy Bourque (Women’s College Research Institute), Jason Brophy (Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario), Ann Burchell (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Allison Carlson (Women’s College Research Institute), Lynne Cioppa (Women’s College Research Institute), Jeffrey Cohen (Windsor Regional Hospital), Tracey Conway (Women’s College Research Institute), Curtis Cooper (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute), Jasmine Cotnam (Women’s College Research Institute), Janette Cousineau (Women’s College Research Institute), Annette Fraleigh (Women’s College Research Institute), Brenda Gagnier (Women’s College Research Institute), Claudine Gasingirwa (Women’s College Research Institute), Saara Greene (McMaster University), Trevor Hart (Ryerson University), Shazia Islam (Women’s College Research Institute), Charu Kaushic (McMaster University), Logan Kennedy (Women’s College Research Institute), Desiree Kerr (Women’s College Research Institute), Maxime Kiboyogo (McGill University Health Centre), Gladys Kwaramba (Women’s College Research Institute), Lynne Leonard (University of Ottawa), Johanna Lewis (Women’s College Research Institute), Carmen Logie (University of Toronto), Shari Margolese (Women’s College Research Institute), Marvelous Muchenje (Women’s Health in Women’s Hands), Mary (Muthoni) Ndung’u (Women’s College Research Institute), Kelly O’Brien (University of Toronto), Charlene Ouellette (Women’s College Research Institute), Jeff Powis (Toronto East General Hospital), Corinna Quan (Windsor Regional Hospital), Janet Raboud (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Anita Rachlis (Sunnybrook Health Science Centre), Edward Ralph (St. Joseph’s Health Care), Sean Rourke (Ontario HIV Treatment Network), Sergio Rueda [Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH)], Roger Sandre (Haven Clinic), Fiona Smaill (McMaster University), Stephanie Smith (Women’s College Research Institute), Tsitsi Tigere (Women’s College Research Institute), Wangari Tharao (Women’s Health in Women’s Hands), Sharon Walmsley (Toronto General Research Institute), Wendy Wobeser (Kingston University), Jessica Yee (Native Youth Sexual Health Network), Mark Yudin (St-Michael’s Hospital). Quebec: Dada Mamvula Bakombo (McGill University Health Centre), Jean-Guy Baril (Université de Montréal), Nora Butler Burke (University Concordia), Pierrette Clément (McGill University Health Center), Janice Dayle (McGill University Health Centre), Danièle Dubuc (McGill University Health Centre), Mylène Fernet (Université du Québec à Montréal), Danielle Groleau (McGill University), Aurélie Hot (COCQ-SIDA), Marina Klein (McGill University Health Centre), Carrie Martin (Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal), Lyne Massie (Université de Québec à Montréal), Brigitte Ménard (McGill University Health Centre), Nadia O’Brien (McGill University Health Centre and Université de Montréal), Joanne Otis (Université du Québec à Montréal), Doris Peltier (Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network), Alie Pierre (McGill University Health Centre), Karène Proulx-Boucher (McGill University Health Centre), Danielle Rouleau (Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal), Édénia Savoie (McGill University Health Centre), Cécile Tremblay (Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal), Benoit Trottier (Clinique l’Actuel), Sylvie Trottier (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec), Christos Tsoukas (McGill University Health Centre). Other Canadian provinces or international jurisdictions: Jacqueline Gahagan (Dalhousie University), Catherine Hankins (University of Amsterdam), Renee Masching (Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network), Susanna Ogunnaike-Cooke (Public Health Agency of Canada). All other CHIWOS Research Team Members who wish to remain anonymous.

Funding

This study was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-111041), the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN 262), the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN), and the Academic Health Science Centres (AHSC) Alternative Funding Plans (AFP) Innovation Fund. CHL is supported by an Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation Early Researcher Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CHL conceptualized the manuscript, contributed to study design and analytic methods, and led writing the manuscript. NM contributed substantially to writing the manuscript. YW conducted data analysis. AK, MRL, ADP were principal investigators and designed the study, contributed substantially to data collection, and provided feedback and edits. KW, VN and TC contributed to study design, data collection, and provided feedback and edits. NO provided feedback and edits and contributed to study design. All authors approved the final manuscript version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the Ethical Standards of the Institutional and/or National Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants provided informed consent before commencing the interview, consistent with the ethics protocol approved by Women’ s College Hospital, University of Toronto (Ontario), Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia/Providence Health (British Columbia), and McGill University Health Centre (Quebec).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Logie, C.H., Wang, Y., Marcus, N. et al. Factors Associated with the Separate and Concurrent Experiences of Food and Housing Insecurity Among Women Living with HIV in Canada. AIDS Behav 22, 3100–3110 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2119-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2119-0