Abstract

A few studies suggest that women who experience intimate partner violence (IPV) are willing to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), but no research has examined mediators of this relationship. The current study used path analysis to examine a phenomenon closely associated with IPV: reproductive coercion, or explicit male behaviors to promote pregnancy of a female partner without her knowledge or against her will. Birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion—two subtypes of reproductive coercion behaviors—were examined as mediators of the relationship between IPV and PrEP acceptability among a cohort of 147 Black women 18–25 years of age recruited from community-based organizations in an urban city. IPV experiences were indirectly related to PrEP acceptability through birth control sabotage (indirect effect = 0.08; p < 0.05), but not to pregnancy coercion. Findings illustrate the importance of identifying and addressing reproductive coercion when assessing whether PrEP is clinically appropriate and a viable option to prevent HIV among women who experience IPV.

Resumen

Algunos estudios sugieren que las mujeres que experimentan violencia de pareja están dispuestas a usar la profilaxis previa a la exposición (PrEP), pero ninguna investigación ha examinado a los mediadores de esta relación. El presente estudio utilizó el análisis de trayectoria para examinar un fenómeno estrechamente asociado con el IPV: coerción reproductiva o comportamientos masculinos explícitos para promover el embarazo de una pareja sin su conocimiento o contra su voluntad. El control del control de la natalidad y la coerción del embarazo -dos subtipos de conductas de coerción reproductiva- fueron examinados como mediadores de la relación entre la aceptación de la violencia de pareja y PrEP en una cohorte de 147 mujeres negras de 18 a 25 años reclutadas de organizaciones comunitarias en una ciudad urbana. Las experiencias de IPV se relacionaron indirectamente con la aceptación de la PrEP a través del sabotaje de control de la natalidad (efecto indirecto = 0,08; p < 0,05), pero no a la coerción del embarazo. Los hallazgos ilustran la importancia de identificar y abordar la coerción reproductiva al evaluar si la PrEP es clínicamente apropiada y una opción viable para prevenir el VIH entre las mujeres que experimentan violencia de pareja.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Linking Reproductive Coercion to Women’s HIV Risk

Reproductive coercion is a constellation of controlling behaviors in which an intimate male partner uses power and control to influence his female sexual partner’s reproductive health outcomes [1–3]. Controlling partners may use birth control sabotage, direct actions to prevent contraception use, and/or pregnancy coercion, verbal pressure and threats to promote pregnancy [3–5]. Examples of birth control sabotage behaviors include removing a condom during sex without the consent of the other partner, purposely putting holes in or breaking a condom, or hiding condoms. Pregnancy coercion behaviors include verbal demands to become pregnant, threats to end the relationship or to have a baby with another partner, or using violence or threats of violence to engage in or force unprotected sex. Birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion have important implications for women’s reproductive health because these behaviors are strongly associated with unintended pregnancy [1].

Reproductive coercion may also have negative consequences on women’s sexual health. In the context of HIV acquisition and susceptibility, reproductive coercion may be a direct or indirect pathway for increased HIV risk among women. For example, preventing a woman from using contraception, including condoms, may directly lead to increased HIV susceptibility. Limiting a woman’s access to birth control could also lower her sexual autonomy, potentially placing her at higher risk for HIV. The risk for transmission is greatest if a woman or her partner engage in sexual risk behaviors such as partner concurrency or sex with multiple partners [6]. Thus, it is critical for researchers to examine the acceptability of innovative women-controlled HIV-prevention methods among women at risk for HIV.

Understanding Reproductive Coercion and HIV Risk Among IPV-Exposed Women

Examining the direct and indirect effects of reproductive coercion on PrEP acceptability may be most salient among women with intimate partner violence (IPV) experiences; they are more likely to report being involved with a male partner who uses reproductive coercion tactics during their relationship [1, 7]. There is a strong relationship between reproductive coercion and IPV [8], and while both experiences can occur within the context of power and control, distinguishing their unique contributions to women’s HIV risk is important. Specifically, reproductive coercion is distinct from IPV because reproductive coercion such as birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion describe behaviors that interfere with women’s ability to make decisions about their reproductive health [8, 9]. Also, reproductive coercion can occur in relationships where IPV is absent and these strategies can be enacted by family members [8, 10]. Although few studies have examined the relationship between reproductive coercion and women’s HIV risk, a growing body of research demonstrates a significant co-occurrence of IPV and HIV [11]. Thus, there is strong evidence that women with experiences of physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner have heightened risks for HIV compared to women in nonviolent relationships [12, 13].

There are several direct and indirect pathways that increase HIV susceptibility and acquisition among women who experience IPV [11, 14]. For example, they may have been sexually assaulted by a male partner who was either HIV-positive or had concurrent sex partners, directly influencing HIV susceptibility [11, 14]. IPV experiences can also indirectly influence HIV susceptibility because women may be unable to negotiate safe sex practices or control their reproductive autonomy with an abusive partner [11]. It is clear that HIV susceptibility and acquisition among women who experience IPV are significantly influenced by a male partner’s behaviors; however, few studies have examined whether men’s use of reproductive coercion strategies may impact women’s health-seeking behaviors. Given the strong associations between reproductive coercion and IPV experiences and the heightened risk for HIV among women enduring violent relationships, it is essential to understand the influential role of reproductive coercion on choices for protection from HIV.

PrEP as a Potential Women-Controlled Strategy

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a promising biomedical HIV prevention method [15, 16] that disrupts potential direct and indirect effects of reproductive coercion on HIV acquisition and susceptibility. Currently, PrEP is a daily oral emtricitabine-tenofovir medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration to reduce HIV incidence among people who are uninfected but who are at high risk for HIV acquisition [17]. PrEP could present an opportunity for women experiencing IPV to expand the number of available prevention options. Women taking PrEP could potentially protect themselves from HIV without disclosing its use to an abusive partner. This is a key women-controlled strategy because women with a history of IPV experiences are more willing to use PrEP compared to women without these experiences [18, 19].

According to the PrEP continuum of care model for men who have sex with men developed by Kelley and colleagues [20], PrEP willingness and acceptability is considered a necessary first step towards uptake. A women-centered PrEP continuum of care model does not yet exist; however, assessment of PrEP acceptability among women with IPV experiences may offer an opportunity to potentially reduce HIV acquisition in this population. Before PrEP can be implemented effectively, associations between IPV and PrEP acceptability are required.

The Need to Focus on Young Black Women Living in Low-Income Communities

Socioeconomically disadvantaged young Black women experience high rates of HIV diagnoses and IPV victimization [21], and are currently overlooked in PrEP research. Low-income young Black women experience multiple structural inequalities due to their race (e.g., racism), gender (e.g., gender pay gap), and class (e.g., unemployment rates). These social forces shape these Black women’s sexual vulnerability, potentially placing them at increased risk for HIV [22, 23]. For example, low access to financial resources and support may limit some Black women’s economic survival, residential security, or mobility. These circumstances can lead some women to seek support by engaging in exchange sexual relationships. Evidence suggests that women’s control over sexual decisions in exchange relationships is often compromised [22].

HIV remains a leading cause of mortality for young Black women in the U.S. [24]. Black women are 20 times more likely to be infected with HIV than women in other racial/ethnic groups [24]. HIV incidence is further complicated by educational disparities because young Black women with a college degree are 73% less likely to report STI and HIV diagnoses than young Black women without a college degree [25]. Furthermore, having less than a college education may directly influence young Black women’s economic status, by increasing the likelihood of living in poverty. Living in low-income communities and lacking access to quality education can accelerate social vulnerabilities, creating an environment in which young Black women are more dependent on their sexual partners; thus, making relationships a critical intervention point for HIV risk reduction [26].

Young Black women’s vulnerability to HIV may be linked to their experiences of IPV. While some research suggests that Black women report significantly higher rates of IPV victimization than some women in other racial/ethnic groups [27, 28], others find that controlling for education and income results in nonsignificant differences [21]. Black women with IPV experiences are also more likely to report engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors and infrequent condom use, which may lead to increased HIV risk [29]. This is particularly concerning since heterosexual sex accounts for 87% of new HIV infections among Black women [24].

Despite this literature, few studies have examined PrEP acceptability among young Black women in the U.S. Among the few studies, Black women seemed to be highly interested and more accepting of PrEP than White women [18, 30]; however, additional research is needed to inform PrEP implementation among this population at high risk for HIV. Thus, the aims of the current study are to: (1) describe the prevalence and associations of IPV, reproductive coercion experiences, and PrEP acceptability among urban-dwelling low-income young Black women, and (2) examine birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion as mediators of the association between IPV and PrEP acceptability.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

All research activities were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Johns Hopkins University, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and Yale University. Study participants self-identified as Black/African-American women ages 18–25 years who reported sex with a man in the six months prior to enrollment (N = 147). Recruitment occurred at six sites between February and July 2014: two youth educational and employment programs, three Women, Infants, and Children’s Programs (WIC), and one community-based organization that focused on linking low-income individuals to health insurance and health services. Flyers and word-of-mouth advertising were used to recruit participants to the study.

Oral informed consent was obtained from each participant due to the sensitive subject of the study. Each participant was asked to complete a questionnaire on a computer tablet in a private area at the recruitment site. The survey assessment tool included 92 items. Survey administration lasted approximately 20–30 min per participant. Upon completion of the questionnaire, research assistants assessed participants for emotional distress and provided a comprehensive health resource list that included support services for IPV, health care, substance use, and mental health. Participants received remuneration of $20 for their participation.

Measures

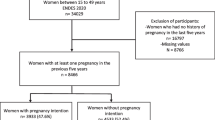

In addition to previous research examining women’s vulnerability to HIV risk, the theory of gender and power [31] was used to guide our measure selection. The theory of gender and power proposes three social structures that influence HIV vulnerability among women: (1) sexual division of labor, (2) sexual division of power, and (3) affective attachment and social norms [31]. These structures exist and are maintained by social mechanisms to produce gender-based inequities and disparities (Fig. 1) [32]. The theory of gender and power is suitable for examination of PrEP acceptability among this study population because, according to this theory, there are economic (e.g., poverty) and physical exposures (e.g., IPV) that can constrain women’s power in heterosexual relationships and place them at greater risk for HIV [31, 32]. Thus, some women could be experiencing gender-based inequities that heighten not only their HIV risk but impact their willingness to consider taking PrEP. Our model includes components of the theory of gender and power and other potentially relevant controlling behaviors such as reproductive coercion.

Intimate Partner Violence

To assess lifetime experiences of physical and sexual violence, items from the subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale 2-Short Form [33, 34] were adapted by asking if they ever occurred rather than how many times they occurred in the past year: (a) Sexual Coercion (2-items: “In your lifetime, has someone you were dating or going out with used force or threats to make you have sex (vaginal, oral, or anal) when you didn’t want to?” and “In your lifetime, has someone you were dating or going out with made you have sex (vaginal, oral, or anal) when you didn’t want to, but didn’t use force or threats?”), and (b) Physical Assault (1-item: “In your lifetime, have you ever been hit, pushed, slapped, choked or otherwise physically hurt by someone you were dating or going out with?”). Concurrent validity between the Short Form and full CTS scale are comparable (0.69 for physical assault scale and 0.67 for sexual assault) [34].

Reproductive Coercion

Lifetime experiences of reproductive coercion were assessed using nine items developed by Elizabeth Miller and colleagues [4]. Women who endorsed one or more of these items were classified as experiencing reproductive coercion. The nine reproductive coercion items were divided into pregnancy coercion (four items) and birth control sabotage (five items). Pregnancy coercion items addressed threats and pressure to promote pregnancy. An example of pregnancy coercion items include “Has someone you were dating or going out with ever told you he would have a baby with someone else if you didn’t get pregnant?” Birth control sabotage items addressed direct interference with use of contraception. An example of a birth control sabotage item includes “Has someone you were dating or going out with ever taken off the condom while you were having sex so that you would get pregnant?” These items demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha for reproductive coercion = 0.91, for birth control sabotage = 0.84, for pregnancy coercion = 0.91).

PrEP Acceptability

To assess participant interest in trying out new ways to prevent getting HIV or STIs, participants were asked a single question, “Would you consider taking a pill every day if you could protect yourself from getting HIV during sex?”

Sociodemographics

Single items were used to assess demographic characteristics including age, relationship status, education level, and gender of sex partners. The questionnaire referred to intimate partners as “someone you were dating or going out with.”

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and Chi square/Fisher’s Exact tests were conducted using SPSS 21 [35] to determine which sociodemographics and key variables were significantly related to birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion. Very little data was missing for sociodemographics: education (<1%) and relationship status (<3%).

The mediation model was conducted using path analysis with MPlus Version 7.0 [36] to determine whether experiences of IPV were indirectly related to PrEP acceptability through birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion. Total direct and total indirect effects—the sum of the specific indirect effects—are provided in the Results section. None of the sociodemographic variables were significantly related to PrEP acceptability and, thus, were not included in the model as covariates. Further, a goodness of fit for the mediation model was determined with the following criteria: a CFI and TLI >0.95, RMSEA <0.06 [37]. To test the significance of the indirect effects, bootstrapping with 5000 re-samples was used, which is optimal for samples <200 [38].

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows characteristics of young Black women enrolled in the study (N = 147). The average age was 21.28 (SD = 2.09). The average household income was 13,496 (SD = 15,529). One in two women (52%) had less than a 12th grade education, 29% finished high school, 16% had some college, and 3% finished college or graduate school. More than half the sample (61%) were dating only one person, 31% were single, 4% were dating more than one person, and 5% were married. A large portion of the women (72%) reported men as their only sex partners whereas 28% reported sexual relationships with both women and men.

Prevalence and Bivariate Associations of PrEP Acceptability, IPV, and Reproductive Coercion

Overall, 77% (n = 114) of the participants reported willingness to use PrEP (Table 1). More than one in two women (52%; n = 77) reported physical or sexual IPV; 29% (n = 42) of the sample reported experiencing birth control sabotage and 21% (n = 31) reported pregnancy coercion. Specifically, 9.5% (n = 14) of the sample reported experiencing only birth control sabotage and 2% (n = 3) reported only pregnancy coercion. Nineteen percent of the sample (n = 28) reported experiencing both types of reproductive coercion.

Women who reported physical or sexual IPV were more likely to report birth control sabotage (p < 0.01) and pregnancy coercion (p < 0.01). Women who were willing to use PrEP were more likely to have experienced birth control sabotage compared to women not willing or indecisive about PrEP (p = 0.05).

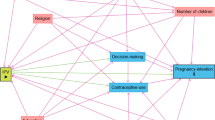

Mediation Model Examining Relationships between IPV, Birth Control Sabotage, Pregnancy Coercion, and PrEP Acceptability

Figure 2 shows the final mediation model with IPV as predictor, birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion as mediators, and PrEP acceptability as the outcome. The overall model was a just identified model (CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00). IPV was directly related to both birth control sabotage (B = 0.40, t = 5.85 p < 0.001) and pregnancy coercion (B = 0.33, t = 4.54, p < 0.001), indicating that young women who reported IPV were more likely to report birth control sabotage and pregnancy coercion than women who did not report IPV. Birth control sabotage was directly related to PrEP acceptability (B = 0.19, t = 1.98 p < 0.05), indicating that young women who experienced birth control sabotage were more likely to be willing to use PrEP. IPV was indirectly related to PrEP acceptability through birth control sabotage, indicating that women with IPV experiences were more willing to use PrEP given their experiences of birth control sabotage. The total indirect effect from IPV to PrEP acceptability (indirect effect = 0.08; p < 0.05) was significant. There were no significant indirect effects from IPV to PrEP acceptability through pregnancy coercion.

Discussion

More than three-quarters of the young women who participated in this study (77%), regardless of lifetime IPV experiences, reported they would be willing to take a daily pill to protect themselves from HIV. The overwhelmingly positive responses to this survey question provide evidence that researchers should further examine innovative ways to provide PrEP to low-income young Black women. While PrEP among heterosexual couples has been shown to increase a person’s chances of preventing HIV from 64 to 84% [39, 40], results have not been consistent across studies [41]. Social factors such as IPV and reproductive coercion as well as PrEP acceptability are important considerations to understand the dynamics of introducing PrEP to women.

Women in the community from which this study sample was drawn have heightened risks for HIV transmission due to their age, race, class, and geographic location. In this study, we identified a group of Black women who reported experiencing IPV at higher rates (52%) than the national average for Black women (43.7%) [21]. However, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey does not include indicators of socioeconomic status for Black women who participated in the survey. Additionally, about one-quarter of the sample in this study reported experiencing reproductive coercion. This finding is almost twice that of previous studies [4, 7]. Although only portions of these studies’ samples were Black women, these findings are consistent with research that demonstrates that Black women living in under-resourced communities experience violence and reproductive coercion at higher rates than women from other racial/ethnic groups [21, 42]. PrEP was found to be a viable and efficacious resource for preventing HIV among women with high-risk demographic and behavioral profiles such as young age and recent unprotected sex or STI infection among the Partners PrEP clinical trial participants in Kenya and Uganda [40]. Many of these are factors or behaviors among women experiencing IPV and, thus, may augment their HIV risks [14, 21]. However, among the cohort of women participating in the Partners PrEP study who reported experiencing recent IPV, PrEP adherence was found to be suboptimal. Measures of IPV in the Partners PrEP did not include sexual violence, thus, more research is needed.

Experiencing birth control sabotage or pregnancy coercion were associated with greater risks for HIV acquisition. The behaviors associated with these two types of reproductive coercion produced direct and indirect pathways to HIV susceptibility. Coercive behaviors such as the clandestine removal of a condom during sexual activity to promote pregnancy, refusal to wear a condom, and making threats to leave a woman if she does not have a baby for her partner—all have implications for a woman’s control over her sexual and reproductive health [43].

Thus, our path analysis findings broaden the scope of understanding ways that IPV-related experiences can influence a woman’s need for greater options for HIV prevention. Birth control sabotage behaviors such as condom removal are discrete, objective, and provide more direct avenues for HIV transmission. This pathway between IPV and PrEP acceptability demonstrates a potential opportunity for clinical or research intervention to modify behaviors. Pregnancy coercion, on the other hand, includes behaviors such as threats which are more indirect. Verbal pressure is often a subjective experience that can be influenced by the complexities of relationship dynamics, intrapsychic experiences, and social factors that may be less amenable to change. Findings from this study highlight nuances found within the constellation of behaviors known as reproductive coercion.

Our study findings also suggest an important overlap of reproductive and sexual health. The women in our study were not only at risk for HIV but, given the high rates of reported reproductive coercion, they were at risk for pregnancy. The potential for PrEP’s utility during pregnancy is not well studied; however, evidence suggests that risks for acquiring HIV are heightened and that acute HIV infection could be transmitted to a developing fetus [44]. Thus, provision of PrEP to women at risk for unintended pregnancies could prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

This age group—emerging adults or young people ages 18–25—are in a developmental stage in which making healthy decisions may be a challenge [39]. The number of trials examining PrEP use among this population is limited [45]; thus, the unique influences of late adolescent brain development on adherence and efficacy to PrEP is unknown. Therefore, future work should consider including larger samples of young men and women.

These findings must be interpreted within the context of IPV-exposed women’s lives. Willingness to take PrEP does not attend to the practical decisions around its implementation as a daily activity. Abusive and controlling male partners may prevent women from accessing medications or services to protect themselves from pregnancy or STIs including HIV [46, 47]. PrEP does not prevent pregnancy or STIs and thus, women will need to continue to find ways to maintain their safety while taking PrEP. Taking a daily pill could exacerbate an already unsafe situation in which power is imbalanced. These are often key reproductive and sexual health concerns expressed by women in violent relationships [48]. Finally, PrEP should be used only by HIV-negative people in potentially risky relationships. Adherence to the HIV testing requirement every three months could present challenges for women experiencing abuse due to associated stigma and shame that can be barriers to testing uptake [49]. Additionally, in the event that a woman has a positive screening test, there is evidence that disclosure of serostatus to a controlling or abusive partner might escalate an already violent situation for a woman [50].

This may be one of the first studies to examine the implications of IPV and reproductive coercion on PrEP acceptability among low-income Black women in the U.S. However, these findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits our ability to make causal inferences. Future studies that are prospective in design will be needed to replicate and add credibility to our finding that birth control sabotage is a mediator between IPV experiences and PrEP acceptability. Second, reproductive coercion and IPV experiences were captured using self-reported data which is susceptible to social desirability bias. This type of bias is likely to result in an underreporting of IPV and reproductive coercion prevalence. Despite this, the majority of violence and coercion studies are based on self-reported measures. Finally, our sample included young Black women residing in socially disadvantaged communities, therefore our findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

PrEP’s utility to the myriad populations that are vulnerable to HIV acquisition is still emerging and largely unknown; however, findings from this study represent a first step to understanding the complexities associated with PrEP implementation in research and clinical settings among young Black women experiencing abuse. Given the high rates of violence found in this sample population, trauma-informed approaches to HIV prevention strategies should include strengthened universal clinical screening policies, comprehensive assessment of IPV and reproductive coercion, and enhanced healthcare provider training efforts to increase safety planning. Recommendations for PrEP initiation should incorporate guiding principles of trauma-informed care including promotion of safety, trust-building, empowerment and choice, and the specialized gender and poverty experiences of Black women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities [51].

References

Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–22.

Miller E, Decker MR, Reed E, Raj A, Hathaway JE, Silverman JG. Male partner pregnancy-promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence: findings from a qualitative study with adolescent females. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(5):360–6.

Obstetricians ACo, Gynecologists. Acog committee opinion no. 554: Reproductive and sexual coercion. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 Pt 1):411.

Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. A family planning clinic partner violence intervention to reduce risk associated with reproductive coercion. Contraception. 2011;83(3):274–80.

Miller E, Decker MR, Raj A, Reed E, Marable D, Silverman JG. Intimate partner violence and health care-seeking patterns among female users of urban adolescent clinics. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(6):910–7.

Brawner BM, Alexander KA, Fannin EF, Baker JL, Davis ZM. The role of sexual health professionals in developing a shared concept of risky sexual behavior as it relates to HIV transmission. Public Health Nurs. 2015.

Clark LE, Allen RH, Goyal V, Raker C, Gottlieb AS. Reproductive coercion and co-occurring intimate partner violence in obstetrics and gynecology patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):42. e41–42. e48.

Grace KT, Anderson JC. Reproductive coercion a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016:1524838016663935.

Miller E, Silverman JG. Reproductive coercion and partner violence: Implications for clinical assessment of unintended pregnancy. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5:511–5.

McCauley HL, Falb KL, Streich-Tilles T, Kpebo D, Gupta J. Mental health impacts of reproductive coercion among women in côte d’ivoire. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2014;127(1):55–9.

Dunkle KL, Decker MR. Gender-based violence and HIV: reviewing the evidence for links and causal pathways in the general population and high-risk groups. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(s1):20–6.

Li Y, Marshall CM, Rees HC, Nunez A, Ezeanolue EE, Ehiri JE. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):18845.

Maman S, Campbell J, Sweat MD, Gielen AC. The intersections of HIV and violence: directions for future research and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(4):459–78.

Stockman JK, Lucea MB, Campbell JC. Forced sexual initiation, sexual intimate partner violence and HIV risk in women: a global review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):832–47.

Underhill K, Operario D, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer MR, Mayer KH. Implementation science of pre-exposure prophylaxis: preparing for public use. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):210–9.

Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. What’s love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (prep) for HIV serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(5):463.

Administration FaD. Truvada for prep fact sheet: Ensuring safe and proper use

Wingood GM, Dunkle K, Camp C, et al. Racial differences and correlates of potential adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis (prep): results of a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(01):S95.

Rubtsova A. M Wingood, G, Dunkle K, Camp C, J DiClemente R. Young adult women and correlates of potential adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis (prep): results of a national survey. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(7):543–8.

Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, et al. Applying a prep continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta GA. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1590.

Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011.

Amaro H, Raj A. On the margin: power and women’s HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7–8):723–49.

Boekeloo B, Geiger T, Wang M, et al. Evaluation of a socio-cultural intervention to reduce unprotected sex for HIV among African American/Black women. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(10):1752–62.

HIV Surveillance report 2011: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013.

Painter JE, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, DePadilla LM, Simpson-Robinson L. College graduation reduces vulnerability to STIS/HIV among African-American young adult women. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(3):e303–10.

Hodder SL, Justman J, Haley DF, et al. Challenges of a hidden epidemic: HIV prevention among women in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 2):S69.

Walton-Moss BJ, Manganello J, Frye V, Campbell JC. Risk factors for intimate partner violence and associated injury among urban women. J Commun Health. 2005;30(5):377–89.

Taft CT, Bryant-Davis T, Woodward HE, Tillman S, Torres SE. Intimate partner violence against African American women: an examination of the socio-cultural context. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(1):50–8.

Stockman J, Campbell J, Campbell D, Sharps P, Callwood G. Sexual intimate partner violence, sexual risk behaviors, and contraceptive practices among women of African descent. Contraception. 2010;82(2):212.

Flash CA, Stone VE, Mitty JA, et al. Perspectives on HIV prevention among urban Black women: a potential role for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014;28(12):635–42.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):539–65.

Panchanadeswaran S, Johnson SC, Go VF, et al. Using the theory of gender and power to examine experiences of partner violence, sexual negotiation, and risk of HIV/AIDS among economically disadvantaged women in Southern India. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2007;15(3–4):155–78.

Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (cts2) development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316.

Straus MA, Douglas EM. A short form of the revised conflict tactics scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004;19(5):507–20.

Nie NH, Bent DH, Hull CH. Spss: Statistical package for the social sciences, vol. 421. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1975.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus. Statistical analyses with latent variables. User’s Guide. 1998;3.

Lt Hu, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2004;36(4):717–31.

Mujugira A, Baeten JM, Donnell D, et al. Characteristics of HIV-1 serodiscordant couples enrolled in a clinical trial of antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e25828.

Murnane PM, Celum C, Nelly M, et al. Efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high-risk heterosexuals: subgroup analyses from the partners prep study. AIDS. 2013;27(13):2155.

Cohen MS, Baden LR. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV—where do we go from here? N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):459–61.

Miller E, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Decker MR, Anderson H, Silverman JG. Recent reproductive coercion and unintended pregnancy among female family planning clients. Contraception. 2014;89(2):122–8.

Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, et al. Recent partner violence and sexual and drug-related STI/HIV risk among adolescent and young adult women attending family planning clinics. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;90:145.

Mugo NR, Heffron R, Donnell D et al. Increased risk of HIV-1 transmission in pregnancy: a prospective study among African HIV-1 serodiscordant couples. AIDS (London, England). 2011;25(15):1887.

Pace JE, Siberry GK, Hazra R, Kapogiannis BG. Preexposure prophylaxis for adolescents and young adults at risk for HIV infection: is an ounce of prevention worth a pound of cure? Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1149–55.

Kazmerski T, McCauley HL, Jones K, et al. Use of reproductive and sexual health services among female family planning clinic clients exposed to partner violence and reproductive coercion. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(7):1490–6.

Silverman JG, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Male perpetration of intimate partner violence and involvement in abortions and abortion-related conflict. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1415–7.

Fontenot HB, Fantasia HC. Do women in abusive relationships have contraceptive control? Nurs Womens Health. 2011;15(3):239–43.

Etudo O, Metheny N, Stephenson R, Kalokhe AS. Intimate partner violence is linked to less HIV testing uptake among high-risk, HIV-negative women in Atlanta. AIDS Care. 2016;1–4.

Karamagi CA, Tumwine JK, Tylleskar T, Heggenhougen K. Intimate partner violence against women in Eastern Uganda: implications for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(1):284.

SAMHSA. Guiding principles of trauma-informed care. 2014. https://newsletter.samhsa.gov/2014/04/30/guiding-principles-trauma-informed-care/.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25-MH087217 and T32MH020031) and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HDO64428).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Willie, T., Kershaw, T., Campbell, J.C. et al. Intimate Partner Violence and PrEP Acceptability Among Low-Income, Young Black Women: Exploring the Mediating Role of Reproductive Coercion. AIDS Behav 21, 2261–2269 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1767-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1767-9