Abstract

Poor adherence remains a major barrier to achieving the clinical and public health benefits of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs). A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis was conduct to evaluate how ARV adverse drug reactions may influence ARV adherence. Thirty-nine articles were identified, and 33 reported that ARV adverse drug reactions decreased adherence and six studies found no influence. Visually noticeable adverse drug reactions and psychological adverse reactions were reported as more likely to cause non-adherence compared to other adverse drug reactions. Six studies reported a range of adverse reactions associated with EFV-containing regimens contributing to decreased adherence. Informing HIV-infected individuals about ARV adverse drug reactions prior to initiation, counselling about coping mechanisms, and experiencing the effectiveness of ARVs on wellbeing may improve ARV adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over 15 million HIV-infected individuals were on antiretroviral therapy (ART) by March 2015 [1]. However, adherence to treatment remains a key challenge for HIV programs to achieve optimal health outcomes and viral suppression [2, 3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines treatment adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behavior-taking medications, following a diet and/or executing lifestyle changes corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider” [4].

ARV adverse drug reactions are an important factor that influences adherence to ARV [5]. WHO defines an adverse drug reaction as “a response which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in humans for the prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for modification of physiological function” [6]. Serious and/or long-term adverse drug reactions can affect adherence to the treatment regimen [7]. There is limited knowledge of how HIV-infected individuals perceive and experience adverse drug reactions to ARVs and how these perceptions and experiences may influence ARV adherence.

Qualitative synthesis focuses on in-depth interpretive explanation of a phenomenon and therefore enables deeper analysis of the complex, multi-faceted experiences of adverse drug reactions and its relation to ARV adherence. The aim of this qualitative synthesis was to systematically review and synthesize the qualitative literature examining how perception and experience of ARV adverse drug reactions influence drug adherence among HIV-infected individuals.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

In accordance with guidance from PRISMA checklist [8], ENTREQ [9], and meta-synthesis guidance from the Cochrane group [10], we used a comprehensive search strategy to identify all relevant studies in English (Search strategy available in supplement). The review protocol (CRD42015017265) was registered (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/). The following electronic journal and dissertation/thesis databases were searched from January 1st, 2000 until February 21st 2015 (to limit to recent ARV drug regimens): CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), EMBASE, LILACS, PsycINFO, PubMed (MEDLINE), Web of Science/Web of Social Science, CINAHL, British Nursing Index and Archive, Social science citation index, AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database), DAI (Dissertation Abstracts International), EPPI-Centre (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre), ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council), Global Health (EBSCO), Anthrosource, and JSTOR. Conference proceedings including the Conferences on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), International AIDS Conference (IAC), and alternating year International AIDS Society (IAS) clinical meetings were searched from their inception dates (1993, 1985 and 2001, respectively). References of included studies were checked and authors were contacted to provide additional information as required.

Studies were selected that used qualitative research designs, including but not limited to ethnographic research, case studies, process evaluations, and mixed methods research. Studies also had to include qualitative data collection techniques (e.g., participant observation, in-depth interview, or focus group) and a qualitative data analysis approach (e.g., framework analysis, or thematic analysis). The review included studies that provided description and interpretation of the impact of adverse drug reactions on adherence for all HIV-infected individuals. We excluded studies that only used quantitative methods to investigate the same phenomenon.

Data Extraction

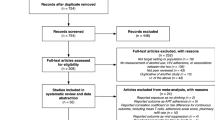

A health sciences librarian conducted the electronic searches and excluded duplicates. All titles were reviewed to examine relevance to the meta-synthesis topic. Two authors (HL & GM) independently reviewed abstracts and made a list of categories for exclusion, and then independently reviewed full text manuscripts and noted reasons for exclusion. Discordance between the two authors was resolved by a discussion with a third author (QM). Studies were reviewed for relevance based on adverse drug reaction’s impact on adherence, study design, main findings and interpretations of findings. (Fig. 1).

A data extraction form was designed specifically for this review. The characteristics extracted from each study included authors, year published, study design, location/orientation of study, key populations and subgroups, age range, main findings, ARV drug regimen, and adverse drug reactions described.

Data Analysis

Prior to conducting the synthesis, each paper’s quality was assessed by both HL and GM using a seven scale criteria tool adapted from the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) [11], which has been used in other reviews [12]. The CERQual approach was used to evaluate the certainty of the review finding [13]. This approach includes an assessment of methodological limitations, coherence, relevance, and adequacy (see the supplement for details), based on a guidance document from the Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group [10, 13]. Thematic synthesis was adopted in the data analysis. A line-by-line coding of the findings of primary studies was conducted by HL and GM prior to organizing into related areas to construct descriptive themes. Analytical themes were developed based on the descriptive themes [14]. Pre-defined subgroup analyses were conducted among specific groups of adults, children and adolescents, and pregnant women. EFV was specifically chosen in the analysis because it has known adverse drug reactions and yet remains first-line therapy in WHO ARV guidelines.

Role of Funding Source

The WHO was a funding source for this study. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The content of the article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of WHO or the National Institutes of Health.

Results

Thirty-nine studies published after 2000 were included in the review. In the CASP assessment, most of the studies reached good quality with the highest score of 7 (17 studies) or 6 (14 studies), while some studies had medium score of 5 (4 studies) and low score of 4 or less (4 studies). Thirty-three out of 39 studies reported that perceived adverse ARV reactions decreased adherence [12, 15–46], whilst six studies [47–52] described no apparent relationship. Nineteen studies [12, 15–27, 29, 32, 36, 44, 47] were conducted in high-income countries, eight [30, 31, 33, 34, 41, 42, 46, 49] in middle-income countries, and twelve [28, 35, 37–40, 43, 45, 48, 50–52] in low-income countries. (Countries—see Tables 1, 2).

The majority of the studies (34/39) sought the perspectives of HIV-infected adults. Two studies considered the views and experiences of children (aged 3–12) and their caregivers [24, 46] and one study of adolescents [45]. Two studies focused on pregnant women [16, 36]. Three studies explored experiences of coping mechanisms for adverse drug reactions as a way of improving adherence [31, 38, 45]. Study characteristics have been summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Eight themes emerged in the thematic synthesis, which included three barriers (i.e., visually noticeable adverse drug reactions, psychological suffering, and Efavirenz (EFV)-containing regimens), three facilitators (i.e., prior knowledge of adverse ARV reactions, coping strategies, and self- perceived effectiveness of ARV), and subgroup analyses among populations of children, adolescents, and pregnant women.

Barriers

Visible Adverse Drug Reactions

Visible adverse drug reactions (e.g., body changes, a buffalo hump, excess sweating, darkening of the skin, body odor, hair loss, weight loss/gain, and skin rash) increased the risk of unintentional HIV disclosure and disturbed HIV-infected individuals’ daily routines. It led to low self-esteem and self-stigmatization among some HIV-infected individuals, and was felt to contribute to poor ARV adherence [15, 19, 21, 23, 25, 28, 29, 32, 35, 38–40, 42, 45, 49, 50]. In several persistent cases, ARV adverse drug reactions caused HIV-infected individuals to undertake long treatment free vacations or quit treatment completely [15, 21, 23, 32, 49]. This finding has a CERQual high level of confidence.

For many participants on ARVs, adverse drug reactions were perceived to be detrimental to adherence [29]. Primary data from the reviewed articles include the following: “I have asked my doctor not to put me on any medication that would make me look like a freak. I would simply not take the drug if I developed a buffalo hump on my back” [23]. “I then had a skin rash to a point where I was so uncomfortable and sick that I stopped taking the medication” [21].

Psychological Suffering

Psychological suffering associated with adverse drug reactions (e.g., being reminded of being sick, delusional, a feeling of being killed by taking the drugs, and getting mad) were occasionally considered to be severe enough to contribute to poor adherence [17, 19, 20, 37, 40, 47, 49]. This finding has a CERQual high level of confidence.

Primary data showed that some participants stopped taking ARVs because they realized that they were not psychologically prepared to take ARVs. For example, participants described: “Just the fact that I have to take it [medication(s)] and knowing that I’m going to have to take it for the rest of my life is having psychological effects, it’s causing trauma to my life right now” [19]. Participants generally used adjectives such as depressing, cranky, moody, sad, angry, guilty, irresponsible, nervous, anxious and afraid to describe their negative psychological problems related to ARVs [20].

Adverse Reactions Associated with EFV-Containing Regimens

Some people receiving EFV-containing regimens reported that neuropsychiatric adverse reactions (e.g., intense body heat, delusions, anxiety, intense dizziness, and nightmares) contributed to poor adherence [47–52]. This finding has a CERQual moderate level of confidence.

Participants described their pain and suffering related to EFV-associated adverse drug reactions: “The numbness crept up from my feet and spread out over my body. Just like with an electrical shock, the feet feel it the worst. During the night, my feet are so sore, numb, and swollen that I can hardly sleep. The pain is so constant. I can hardly close my eyes” [49]. “I can’t say that they have worked well because as you see now my face it has changed from its normal shape, I don’t know whether it is a type of drug or it is because I have spent some time on them” [50].

Facilitators

Prior Knowledge of Adverse ARV Reactions

When people receiving ART had prior knowledge of ARV adverse drug reactions, or had been informed in advance of potential adverse reactions and how to manage them, they felt these reactions were expected, normal and manageable, and therefore reported less non-adherence [35, 38, 48, 50]. This finding has a CERQual moderate level of confidence.

Participants described their experiences: “We were warned that some people would get drug reactions. This helped me not to worry when I fell sick” [38]. “That’s normal stuff” [48]. “Those things occur, and after a time they go away” [48]. For those participants who were informed about potential adverse effects of ARVs prior to treatment initiation, the reactions were not reported as reasons for non-adherence [48]. Participants wished they had been pre-informed about the adverse effect profile at the initiation of treatment, so that they know how to manage these effects [35].

Coping Strategies

When people receiving ART developed coping strategies to cope with adverse events (e.g., drinking a lot of fluids and resting to reduce dizziness, or eating a snack or meal before swallowing pills to control nausea), they expressed good levels of adherence [31, 38, 45]. This finding has a CERQual moderate level of confidence.

Participants described how they dealt with adverse drug reactions: “I have abdominal distention. I felt so uncomfortable even if I only ate a little. I felt that the food was stuck there and was not digested. Taking some herb digestion medicine makes me feel better” [31]. A number of strategies were also employed to disguise visible adverse effects. For example, women reported wearing dark nail polish to cover darkened nails and wearing long sleeved clothes, ankle reaching skirts and trousers to cover body sores [38].

Perceived Effectiveness of ARVs

When people on ART experienced individual benefits of taking ARVs on their health (e.g., regaining physical strength, being more independent, and able to help with domestic work again), they achieved greater adherence independent of the adverse effects [30, 31, 45, 48]. This finding has a CERQual moderate level of confidence.

Participants described benefits of ARVs as a reason to adhere to medication as follows: “I say ARVs are medicine [e.g., effective medicine, not fake]. Because basing it off my health, I had lots of sores all over my body, on my arms, in my mouth, on my head, on my private parts, you understand? …After being started on the drugs, all those sores went away, my health status started to improve, and I was able to eat well. Until now after coming to test recently I had a CD4 of like 181. So it has risen well. It’s these meds [that do it], man” [48]. “I cannot live without these meds. If I did not take them, I might die very soon. The benefit of the meds is they enable me to survive a few more days. As patients, our lives have been shortened by HIV, but ART can extend our lives a little bit longer. Taking meds on time can prolong my life” [31].

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup Analyses Among HIV-Infected Children and Adolescents

The experience of drug attributed adverse events (e.g., queasy feeling, vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, insatiable hunger, and skin sores) resulted in children’s refusal to take ARVs (e.g., coughing, gagging, and throwing it up) [24, 45, 46]. This finding has a CERQual moderate level of confidence.

For example, an adolescent said, “There is this one [pill] at night that makes you feel dizzy, that one bothersome a lot. I keep taking them, and then sometimes they […] provoke these scabs. Those others provoke wounds […], they damage your face. So these ARVs […] and my body don’t get along” [45].

Subgroup Analyses Among HIV-Infected Pregnant Women

Pregnant women perceived that the likelihood of their unborn baby suffering from ARV adverse effects was greater than the likelihood of their unborn baby acquiring HIV infection [36]. ARVs also worsened their pregnancy-associated nausea, hence they felt that ARVs did more harm than good [16, 36]. This finding has a CERQual low level of confidence.

For example, a woman described: “When you are pregnant, the thing about taking zidovudine (AZT) is that, it is so strong. Taking AZT is like taking drugs, it’s like taking marijuana or smoking crack…it’s like the baby is gonna be born with that in his system” [16].

Discussion

This synthesis identified 39 qualitative studies from diverse countries. Most of the studies supported that occurrence of ARV adverse drug reactions are associated with ARV non-adherence. This is consistent with quantitative research demonstrating that adverse drug reactions contribute to poor adherence with treatment interruptions [53–56]. This synthesis formally evaluated the qualitative evidence and extended the literature in three ways: (1) proposing barriers that likely contribute to non-adherence (2) exploring facilitators to improve adherence, and (3) uncovering challenges among specific groups.

This qualitative synthesis explored potential neuropsychological mechanisms of subjective perceptions and experiences influencing ARV adherence. This is consistent with cross-sectional data correlating subjective perceptions of ARVs and adherence [55, 56]. Cross-sectional and cohort studies showed that depression, anxiety, negative cognitive and psychosocial functioning were frequently associated with poorer ARV adherence [57, 58]. This synthesis suggested that the experiences of taking ARVs were associated with significant psychological trauma and emotional suffering in some HIV-infected individuals. In particular, the trauma and constraints were usually related to being on a lifelong therapy associated with HIV infection. Also, visually noticeable adverse drug reactions could disturb daily routines and threaten HIV disclosure and embarrassment in public, which might in turn increase psychological and emotional burden. This suffering may further exacerbate self-stigmatization and further decrease the self-esteem of HIV-infected individuals. When this suffering is not effectively addressed, it may contribute to ARV non-adherence.

Even though some ARV drugs (e.g., stavudine) has been recommended to be phased out [59]. This qualitative synthesis highlighted this concern and provided descriptions of adverse drug reactions related to EFV-containing regimens contributing to poor adherence. This is consistent with several quantitative meta-analysis demonstrating the association between EFV use and central nervous system (CNS) toxicity [60] and treatment non-adherence [61]. Shubber and colleagues’ systematic review described that around a third of people using EFV experienced CNS adverse reactions (e.g., dizziness, abnormal dreams) with variable degree of severity, which are usually mild and transient [62]. However, Shubber and colleagues’ review showed that compared to nevirapine, EFV was associated with a lower frequency of severe adverse reactions, particularly in treatment discontinuation among both adult and children populations [62]. A recent review [63] on comparative safety of EFV and impact of CNS adverse events showed 90 % of patients remaining on EFV (78 weeks). Even though the relative risk of treatment discontinuation due to EFV-related adverse events was higher than that related to other 1st line options (e.g., tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, abacavir, dolutegravir, raltegravir), the absolute differences were low (<5 %) [63]. Although the overall frequency of EFV adverse medication reactions remains rare, our findings suggest that EFV-containing regimens are perceived by PLWH as related to adverse reactions influencing their lives, appearance, and well-being.

Another important finding of this qualitative synthesis is that the HIV-infected individuals’ experience, perception, understanding, and knowledge of adverse drug reactions were related to ARV adherence. When people receiving ART experienced ARVs maintaining their health effectively, had knowledge of adverse ARV reactions, and practiced coping strategies to manage these reactions, they were more likely on adherence. This is consistent with previous quantitative studies that having knowledge about adverse drug reactions, adherence self-efficacy, self-management, and individual strategies for fitting medication into daily routines were associated with ARV adherence [64, 65]. However, researchers also argued that extensive communicating about potential adverse medication reactions may increase the likelihood of a patient developing those reactions [66]. A simplified and structured informing approach about potential adverse drug reactions to ARV is needed.

This qualitative synthesis found very limited studies considering perspectives of children, adolescent, and pregnant women, and the findings were in moderate and low confidence levels respectively. For children and adolescents, refusal of ARVs or doses skipping were related to pediatric adherence barriers, such as feeling sick and needing a break [67], palatability of medication, large medication volumes, and limited treatment options [68, 69]. For pregnant women and women with history of childbirth, some important issues were emerging that they perceived ARVs as medically powerful and full of potential adverse effects, which made these women felt that ARVs did more harm than good. For this specific group of women, ARV adherence became more complicated.

This qualitative synthesis is subject to some limitations. First, some of the reviewed articles are weak in research design or have incomplete reporting. However, we evaluated the quality of individual studies and this quality assessment was reflected in the overall confidence assessment using CERQual. Second, most of the reviewed articles emphasized adults with HIV and few specifically focused on children, adolescents or pregnant women. It is therefore difficult to generalize the findings to other specific sub populations. Third, our qualitative synthesis only provided subjective interpretation of the relationship between patient attributed adverse drug reactions and ARV non-adherence and causal pathways could only be inferred.

Despite these limitations, this synthesis found that visually noticeable drug reactions, emotional and psychological suffering, and EFV-containing regimens may be related to non-adherence for HIV-infected individuals. This synthesis also found that improved knowledge and understanding of adverse ARV reactions, experiencing the health benefits of ARVs, and strategies of coping and self-management were practically important in addressing the problem of ARV non-adherence caused by adverse drug reactions. It’s therefore important to provide HIV-infected individuals tailored counselling to enhance knowledge and understanding of adverse ARV reactions and to train and support people receiving ART how to adopt multiple strategies to deal with these reactions. Moreover, this synthesis provided directions for future studies. Vulnerable children, adolescents, and pregnant women are still far under studied in the qualitative literature on their experience and perception related to adherence of ARVs. Future qualitative studies should focus on exploring subjective experiences and perceptions of ARV adverse drug reactions and strategies being used to manage these reactions from the perspective of children, adolescents, and pregnant women.

References

UNAIDS. UNAIDS FACT SHEET 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/HowAIDSchangedeverything/factsheet. Accessed 15 May 2015.

Sungkanuparph S, Oyomopito R, Sirivichayakul S, Sirisanthana T, Li PCK, Kantipong P, et al. HIV-1 drug resistance mutations among Antiretroviral-Naı¨ve HIV-1 infected patients in Asia: results from the TREAT Asia studies to evaluate resistance-monitoring study. Clinical Infect Dis. 2011;52:1053–7.

WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities summary. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progressreports/update2013/en/. Accessed 7 July 2015.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, 2014. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/keypopulations/en/. Accessed 12 May 2015.

Veloso VG, Velasque LS, Grinsztejn B, Torres TS, Cardoso SW. Incidence rate of modifying or discontinuing first combined antiretroviral therapy regimen due to toxicity during the first year of treatment stratified by age. Braz J infect dis. 2014;18:34–41.

WHO. Surveillance of antiretroviral drug toxicity during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Geneva, World Health Organization 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/91768?mode=full. Accessed 9 June 2015.

Nadkar MY, Bajpai S. Antiretroviral therapy: toxicity and adherence. JAPI. 2009;57:375–6.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e100009.

Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181.

Noyes JSL. Supplemental guidance on selecting a method of qualitative evidence synthesis, and integrating qualitative evidence with Cochrane intervention reviews. In: Noyes J, Booth A, Hannes K, editors. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Oxford: Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group; 2011.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist, 2006. http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_951541699e9edc71ce66c9bac4734c69.pdf. Accessed 5 March 2015.

Monroe AK, Rowe TL, Moore RD, Chander G. Medication adherence in HIV-positive patients with diabetes or hypertension: a focus group study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:488.

Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gulmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001895.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45.

Laws MB, Wilson IB, Bowser DM, Kerr SE. Taking antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: learning from patients’ stories. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:848–58.

Siegel K, Lekas HM, Schrimshaw EW, Johnson JK. Factors associated with HIV-infected women’s use or intention to use AZT during pregnancy. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13:189–206.

Pugatch D, Bennett L, Patterson D. HIV medication adherence in adolescents: a qualitative study. J HIV/AIDS Prev Educ Adolesc Child. 2002;5:9–29.

Witteveen E, Van Ameijden EJC. Drug users and HIV-combination therapy (HAART): factors which impede or facilitate adherence. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37:1905–25.

Abel E, Painter L. Factors that influence adherence to HIV medications: perceptions of women and health care providers. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2003;14:61–9.

Powell-Cope GM, White J, Henkelman EJ, Turner BJ. Qualitative and quantitative assessments of HAART adherence of substance-abusing women. AIDS Care. 2003;15:239–49.

Remien RH, Hirky AE, Johnson MO, Weinhardt LS, Whittier D, Le GM. Adherence to medication treatment: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers among a diverse sample of HIV + men and women in four US cities. AIDS Behav. 2003;7:61–72.

Westerfelt A. A qualitative investigation of adherence issues for men who are HIV positive. Soc Work. 2004;49:231–9.

Prutch PT. Understanding the nature of medication adherence issues with the HIV-infected patient in the family practice setting [Ph.D.]. Ann Arbor: Colorado State University; 2005:85-85.

Roberts KJ. Barriers to antiretroviral medication adherence in young HIV-infected children. Youth Soc. 2005;37:230–45.

Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K, Lekas HM. Changes in attitudes toward antiviral medication: a comparison of women living with HIV/AIDS in the pre-HAART and HAART eras. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:267–79.

Alfonso V, Bermbach N, Geller J, Montaner JS. Individual variability in barriers affecting people’s decision to take HAART: a qualitative study identifying barriers to being on HAART. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:848–57.

Golub SA, Indyk D, Wainberg ML. Reframing HIV adherence as part of the experience of illness. Socl Work Health Care. 2006;42:167–88.

Hardon AP, Akurut D, Comoro C, Ekezie C, Irunde HF, Gerrits T, et al. Hunger, waiting time and transport costs: time to confront challenges to ART adherence in Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19:658–65.

Beusterien KM, Davis EA, Flood R, Howard K, Jordan J. HIV patient insight on adhering to medication: a qualitative analysis. AIDS Care. 2008;20:251–9.

Dahab M, Charalambous S, Hamilton R, Fielding K, Kielmann K, Churchyard GJ, et al. “That is why I stopped the ART”: patients’ & providers’ perspectives on barriers to and enablers of HIV treatment adherence in a South African workplace programme. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:63.

Chen WT, Shin CS, Simoni J, Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Zhang FJ, Starks H, et al. Attitudes toward antiretroviral therapy and complementary and alternative medicine in Chinese patients infected with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:203–17.

Vervoort SCJM, Grypdonck MHF, De Grauwe A, Hoepelman AIM, Borleffs JCC. Adherence to HAART: processes explaining adherence behavior in acceptors and non-acceptors. AIDS Care. 2009;21:431–8.

Curioso WH, Kepka D, Cabello R, Segura P, Kurth AE. Understanding the facilitators and barriers of antiretroviral adherence in Peru: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:13.

Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Dvoryak S, Reisner SL, Needle R, Woody G. “We fear the police, and the police fear us”: structural and individual barriers and facilitators to HIV medication adherence among injection drug users in Kiev. Ukraine. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1305–13.

Nsimba SED, Irunde H, Comoro C. Barriers to ARV adherence among HIV/AIDS positive persons taking anti-retroviral therapy in two Tanzanian regions 8–12 months after program initiation. J AIDS Clin Res. 2010;1:110–1.

McDonald K, Kirkman M. HIV-positive women in Australia explain their use and non-use of antiretroviral therapy in preventing mother-to-child transmission. AIDS Care. 2011;23:578–84.

Musheke M, Bond V, Merten S. Individual and contextual factors influencing patient attrition from antiretroviral therapy care in an urban community of Lusaka. Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl 1):1–9.

Nyanzi-Wakholi B, Lara AM, Munderi P, Gilks C. The charms and challenges of antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: the DART experience. AIDS Care. 2012;24:137–42.

Wasti SP, Simkhada P, Randall J, Freeman JV, Teijlingen EV. Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral treatment in Nepal: a mixed-methods study. PLoS One. 2012;7:1–11.

Wasti SP, Simkhada P, Randall J, Freeman JV, van Teijlingen E. Barriers to and facilitators of antiretroviral therapy adherence in Nepal: a qualitative study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30:410–9.

Barnett W, Patten G, Kerschberger B, Conradie K, Garone DB, Van Cutsem G, et al. Perceived adherence barriers among patients failing second-line antiretroviral therapy in Khayelitsha, South Africa. S Afr J HIV Med. 2013;14:170–6.

Lekhuleni ME, Mothiba TM, Maputle MS, Jali MN. Patients’ adherence to antiretroviral therapy at antiretroviral therapy sites in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr J Phys Health Educ Recreat Dance. 2013;19:75–85.

Vyankandondera J, Mitchell K, Asiimwe-Kateera B, Boer K, Mutwa P, Balinda JP, et al. Antiretroviral therapy drug adherence in Rwanda: perspectives from patients and healthcare workers using a mixed-methods approach. AIDS Care. 2013;25:1504–12.

Krummenacher I, Spencer B, Du Pasquier S, Bugnon O, Cavassini M, Schneider MP. Qualitative analysis of barriers and facilitators encountered by HIV patients in an ART adherence programme. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:716–24.

Mattes D. “Life is not a rehearsal, it’s a performance”: an ethnographic enquiry into the subjectivities of children and adolescents living with antiretroviral treatment in Northeastern Tanzania. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;45:28–37.

Peraza MC, Gonzalez I, Perez J. Factors related to antiretroviral therapy adherence in children and adolescents with HIV/AIDS in cuba. MEDICC Rev. 2015;17:35–40.

Brion JM, Menke EM. Perspectives Regarding Adherence to Prescribed Treatment in Highly Adherent HIV-Infected Gay Men. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19:181–91.

Beckham S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapies in resource-poor settings: A mixed-methods case study in rural Tanzania [M.P.H.]. Ann Arbor: Yale University; 2009:108.

Chen WT, Shiu CS, Yang JP, Simoni JM, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Lee TS, et al. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) Side effect impacted on quality of life, and depressive symptomatology: a mixed-method study. J AIDS Clin Res. 2013;4:218.

Mbonye M, Seeley J, Ssembajja F, Birungi J, Jaffar S. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Jinja, Uganda: a six-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78243.

Bezabhe WM, Chalmers L, Bereznicki LR, Peterson GM, Bimirew MA, Kassie DM. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to antiretroviral drug therapy and retention in care among adult HIV-positive patients: a qualitative study from Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97353.

McKinney O, Modeste NN, Lee JW, Gleason PC, Maynard-Tucker G. Determinants of antiretroviral therapy adherence among women in Southern Malawi: healthcare providers’ perspectives. AIDS Res Treat. 2014;2014:1–9.

de Bonolo PF, César CC, Acúrcio FA, Ceccato MGB, de Pádua CAM, Álvares J, et al. Non-adherence among patients initiating antiretroviral therapy: a challenge for health professionals in Brazil. AIDS. 2005;19:S5–13.

Horne R, Buick D, Fisher M, Leake H, Cooper V, Weinman J. Doubts about necessity and concerns about adverse effects: identifying the types of beliefs that are associated with non-adherence to HAART. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:38–44.

Stone VE, Jordan J, Tolson J, Miller R, Pilon T. Perspectives on adherence and simplicity for HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy—self-report of the relative importance of multiple attributes of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens in predicting adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:808–16.

de Menezes Padua CA, Cesar CC, Bonolo PF, Acurcio FA, Guimaraes MDC. Self-reported adverse reactions among patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:20–6.

Schuman P. Prescription of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among women with AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2001;5:371–8.

Wagner GJ, Kanouse DE, Koegel P, Sullivan G. Correlates of HIV antiretroviral adherence in persons with serious mental illness. AIDS Care. 2004;16:501–6.

WHO. Phasing Out Stavudine: Progress and Challenges. Supplementary section to the 2013 WHO consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection, Chapter 9—Guidance on operations and service delivery. www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/arv2013supplement_to_chapter09.pdf. Accessed 10 Sept 2015.

Muñoz-Moreno JA, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, González-García M, Moltó J, Negredo E, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with efavirenz: prevalence, correlates, and management. A neurobehavioral review. AIDS Rev. 2009;11:103–9.

Kryst J, Kawalec P, Pilc A. Efavirenz-based regimens in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124279.

Shubber Z, Calmy A, Andrieux-Meyer I, Vitoria M, Renaud-Théry F, Shaffer N, et al. Adverse events associated with nevirapine and efavirenz-based first-line antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2013;27:1403–12.

Ford N, Shubber Z, Pozniak A, Vitoria M, Doherty M, Kirby C, et al. Comparative safety and neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with efavirenz use in first-line antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:422–9.

Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Morin SF, Charlebois E, et al. Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: findings from the Healthy Living Project. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17:645–56.

Wang X, Wu Z. Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV/AIDS patients in rural China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S149–55.

Kaptchuk TJ, Miller FG. Placebo effects in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:8–9.

MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:86–93.

Brackis-Cott E, Mellins CA, Abrams E, Reval T, Dolezal C. Pediatric HIV medication adherence: the views of medical providers from two primary care programs. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17:252–60.

Coetzee B, Kagee A, Bland R. Barriers and facilitators to paediatric adherence to antiretroviral therapy in rural South Africa: a multi-stakeholder perspective. AIDS Care. 2015;27:315–21.

Acknowledgments

HL, GM, WM, CW, FR, JT conceived and designed the protocol and study. ML, HL, GM, QM acquired the data. HL, GM, JT analyzed the data. HL and GM drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in critically appraising the content and approving the final version.

Funding

This study was funded by the WHO HIV Department, NIAID 1R01AI114310-01, and FIC 1D43TW009532-01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

RB is an affiliated consultant with the World Health Organization and receives remuneration for work related to the topic of this paper. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Marley, G., Ma, W. et al. The Role of ARV Associated Adverse Drug Reactions in Influencing Adherence Among HIV-Infected Individuals: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. AIDS Behav 21, 341–351 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1545-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1545-0