Abstract

We sought to examine the prevalence and correlates of HIV-disclosure among treatment-experienced individuals in British Columbia, Canada. Study participants completed an interviewer-administered survey between July 2007 and January 2010. The primary outcome of interest was disclosing one’s HIV-positive status to all new sexual partners within the last 6 months. An exploratory logistic regression model was developed to identify variables independently associated with disclosure. Of the 657 participants included in this analysis, 73.4 % disclosed their HIV-positive status to all of their sexual partners. Factors independently associated with non-disclosure included identifying as a woman (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.92; 95 % confidence interval [95 % CI] 1.13–3.27) or as a gay or bisexual man (AOR 2.45; 95 % CI 1.47–4.10). Behaviours that were independently associated with non-disclosure were having sex with a stranger (AOR 2.74; 95 % CI 1.46–5.17), not being on treatment at the time of interview (AOR 2.67; 95 % CI 1.40–5.11), and not always using a condom (AOR 1.78; 95 % CI 1.09–2.90). Future preventative strategies should focus on environmental and social factors that may inhibit vulnerable HIV-positive populations, such as women and gay or bisexual men, from safely disclosing their positive status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The act of disclosing one’s HIV serostatus to a sexual partner has been shown to significantly reduce the transmission of HIV by upwards of 40 % [1]. The adoption of preventative behaviors including increased condom use, a reduction in the number of sexual partners and increased efforts to access care and testing for both sexual partners may be increased following more frequent disclosure to a sexual partner [2–7]. While there are potential preventative benefits gained from disclosing a positive serostatus, research has found that this individual act must be contextualized within the social and structural setting where HIV disclosure may or may not take place [8]. Perceived advantages to disclosing may be outweighed by financial consequences, social exclusion, violence, discrimination, abandonment, and stigmatization [9–13]. Research suggests that situating disclosure as an individual responsibility may result in individual-level consequences such as sexual rejection, stigma, and a loss of privacy [14–17]. The criminalization of non-disclosure, which many jurisdictions globally are confronting, may also increase stigma associated with HIV infection and further places the responsibility of discussing serostatus solely on the part of the HIV-positive individual [18].

Considering these potential social and structural barriers, it is clear that disclosing one’s positive status cannot be understood without considering the social and environmental context within which sexual relationships and behaviors are negotiated [19]. Research has found that rates of disclosure and perceived consequences and social threats associated with disclosure vary significantly by individual sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics [20–23]. There is evidence that gay and bisexual men typically report lower rates of disclosure when compared to heterosexual men [24, 25]. Perceptions of HIV-related stigma may play an important role in gay and bisexual men’s decision to disclose as negative attitudes towards HIV and AIDS have been closely linked with prejudice towards homosexuals and bisexuals [26, 27]. In addition to sexual orientation, literature suggests that gender is also an important distinguishing factor with some studies demonstrating higher rates of disclosure among women [20, 21, 24]. Marks and Crepaz [14] found that sexual acts associated with increased vulnerability to HIV infection, i.e. unprotected insertive or receptive anal intercourse or unprotected vaginal intercourse, were also associated with lower rates of disclosure. This is corroborated in the research finding that disclosure is closely tied to sexual practices [28]. Understanding the association between sexual practices that result in an increased vulnerability to HIV and patterns of disclosure have important public health implications and will provide greater insight into the nuances and complexities of disclosure.

The objective of this study is to characterize the prevalence and correlates of serostatus disclosure among a sample of treatment-experienced HIV-positive individuals in British Columbia (BC), Canada.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

The Drug Treatment Program at the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS (BC-CfE) is mandated by the government to distribute antiretroviral therapy (ART) free-of-charge to all eligible HIV-positive persons requiring treatment in the province of BC. The BC-CfE distributes ART through the province according to the guidelines set by the Therapeutic Guideline Committee, which are based upon those established by the International AIDS Society USA [29].

The Longitudinal Investigations into Supportive and Ancillary health services (LISA) study is a sample of 1,000 HIV-positive persons who had ever been on ART in BC. To be eligible, participants were at least 19 years of age, had initiated ART in BC, were able to provide informed consent, and completed an interviewer-administered survey between July 2007 and January 2010. Study participants were actively recruited through letters distributed by physicians or pharmacists, word-of-mouth, and advertisements at HIV/AIDS clinics and service organizations. Particular sub-populations were deliberately over-sampled for analytical purposes; consequently, women, injection drug users, and Aboriginals are overrepresented in the cohort.

Study Instrument and Ethical Approval

Study participants completed a comprehensive interviewer-administered survey which captured a range of variables including: basic demographic data, housing, income, social support networks, mental health disorders, drug and alcohol use, and quality of life measures. Clinical variables, such as CD4 count, plasma viral load, and prescription-based adherence were obtained through a linkage with the provincial drug treatment program at the BC-CfE. Surveys took ~1 h to complete and participants were offered a $20 honorarium as compensation for their time. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ethical research boards.

Outcome and Explanatory Variables

The primary outcome variable of interest was disclosure of HIV-positive status to all new sexual partners. Participants were asked if in the last 6 months, they disclosed their HIV+ status to all new sexual partners. The available responses included, “not applicable (N/A)”, “always (100 % of the time)”, “usually (~75 %)”, “sometimes (~50 %)”, “occasionally (~25 %)”, or “hardly ever (<10 %)”. Answers were then dichotomized into always disclosing and not always disclosing by collapsing the answers “usually”, “sometimes”, “occasionally” or “hardly ever” into one outcome. Respondents who answered “not applicable” were excluded from the analysis. Participants may have answered “not applicable” either because they did not have a sexual partner in the last 6 months or they have had the same sexual partner over this interval of time.

Explanatory variables were identified through a literature review and were included in the bivariable and multivariable analyses. Potential covariates were arranged by demographic, clinical, socio-behavioral, beliefs and behavioral factors. Demographic factors included age, gender, sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay or bisexual), ethnicity (aboriginal and other groups), annual income, and year of HIV diagnosis. Income was dichotomized into those participants who made either more than or less than $15,000 CDN per year, based on Canada’s low-income cutoff.

Clinical variables included CD4 cell counts (cells/mm3) and viral loads (copies/mL) at the time of the interview, or the most recent data available within 6 months prior to interview date. Adherence was assessed through pharmacy refill compliance and was defined as the number of days for which treatment was dispensed divided by the number of days for which treatment was prescribed in the 12 months prior to the interview. Adherence was dichotomized as <95 % (suboptimal) and ≥95 % (optimal).

Two additional variables were included with respect to attitudes on viral load as a risk reduction strategy. Participants were read the statements “I believe that an undetectable viral load means I cannot transmit HIV”, and “I believe taking HIV meds will protect my sexual partner from getting HIV”. Participants were then asked if they “strongly agreed”, “agreed”, were “neutral”, “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” with each of the statements. The variables were then dichotomized, by collapsing the responses of “strongly agree”, “agree” or “neutral” and “disagree” or “strongly disagree”.

Socio-behavioral covariates included history of injection drug use, current alcohol use, exposure to violence, sexual behavior and relationship status. For drug and alcohol use behavior, current use was defined as self-reported in the 3 months preceding the interview. In this analysis, injection drugs included injection of cocaine, crack, heroin, speedball (heroin and cocaine), or methamphetamine. Information on sexual behavior included type of partner, number of partners in the last 6 months, number of sex acts in the last 6 months, condom use, and whether they are less likely to use a condom with a sexual partner that is also HIV-positive. The type of sexual partner was broken down into “has had sex with strangers (including sex workers)”, “sex only with regular partners” and “have had casual sex”, and was followed up by asking how often they used condoms during different sexual acts (vaginal and/or anal sex). The variables were then dichotomized into either the “always used condom” category or the “not always” category for each different type of sex act.

Statistical Analysis

Participants were categorized into either always or not always disclosing their HIV status to new sexual partners. Baseline categorical variables were compared in a bivariate analysis using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Variables with a significant p value (<0.05) in the bivariable analysis were considered potential factors associated with not always disclosing one’s HIV status to a new sexual partner and were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model. A backward stepwise technique, minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), was used in the selection of covariates [30]. Linearity of the continuous explanatory variables was assessed via cumulative residuals techniques [31]. The concordance index was used to assess the predictive power of the model. The process was repeated for a sub-analysis of bisexual and gay men and another of women in the LISA cohort. All analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.1.3, service pack 3).

Results

Table 1 demonstrates the representativeness of the sample, comparing LISA participants with all HIV-positive participants on therapy in the drug treatment program across the province that were eligible for participation in the LISA study. As shown in Table 1, LISA participants more likely to have a history of injection drug use (71.3 vs. 28.4 %; p ≤ 0.001), to be women (27.4 vs. 16 %; p ≤ 0.001), to report an aboriginal ancestry (31.5 vs. 6.7 %; p ≤ 0.001), and to have a baseline suboptimal adherence (48.6 vs. 39.9 %; p ≤ 0.001).

For this study, four LISA participants were excluded, because they did not complete the disclosure portion of the survey and 256 (25.6 %) were excluded because they were not in a current sexual relationship with a new sexual partner and thus the disclosure questions were not relevant. Of the sample of 657 participants used in this study, 482 (73.4 %) reported disclosing their HIV status all the time.

The bivariable analysis compares those study participants who did and did not disclose their HIV status to all their sexual partners (Table 2). Those who do not disclose were more likely to be women (32.0 vs. 25.7 %; p ≤ 0.0001) and gay or bisexual men (48.6 vs. 32.8 %; p ≤ 0.0001). Non-disclosure was also more likely to be attributed to individuals who were younger (median age; 43 vs. 45 years, p = 0.009), single or out of a relationship (68 vs. 63.5 %, p = 0.0350), and not on ART at time of interview (13.1 vs. 5.2 %, p = 0.0011).

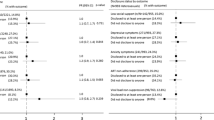

This study identified independent predictors of disclosure to all new sexual partners. As shown in Table 3, women (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.92; 95 % confidence interval [95 % CI] 1.13–3.27) and gay or bisexual men (AOR 2.45; 95 % CI 1.47–4.10) were more likely to not disclose their status to their sexual partners than heterosexual men. Participants who were not on ART were more likely to not disclose (AOR 2.67; 95 % CI 1.40–5.11) than those on ART at the time of the interview. Participants who had sex with strangers were more likely to not disclose (AOR 2.74; 95 % CI 1.46–5.17) than those who reported only having sex with regular partners. Participants who reported ever having sex without a condom (AOR 1.78; 95 % CI 1.09–2.90) had greater odds of non-disclosure than those who reported using condoms 100 % of the time. Also, individuals who reported having five or more partners in the past six months (unadjusted odds ratio [UOR]: 3.53, 95 % CI 2.03–6.15) had greater odds of non-disclosure than those who had sex with only one sexual partner. Identifying as aboriginal increased odds of not disclosing, compared to all other ethnicities (AOR 1.64; 95 % CI 1.05–2.56) (Tables 4, 5, 6, 7).

A sub-analysis of 189 women was completed to look at unique factors associated with disclosure. Women who were younger (AOR 0.93; 95 % CI 0.88–0.98), off ART at time of interview (AOR 3.05; 95 % CI 1.11–8.40), and more likely to have sex with strangers versus regular partners (AOR 5.20; 95 % CI 1.76–15.37) were more likely not to disclose. Furthermore, women that were more likely to use a condom with a HIV-positive partner were less likely not to disclose (AOR 0.24; 95 % CI 0.10–0.57).

A sub-analysis of 243 gay and bisexual men was completed to look at unique factors associated with disclosure. In the multivariable analysis of gay and bisexual men, those men who did not disclose were significantly more likely have 6 or more partners (AOR 7.68; 95 % CI 2.46–24.00) or 2–5 partners (AOR 3.16; 95 % CI 1.19–8.40), when compared to those men who disclose.

Discussion

This is the first study in British Columbia, where ART is available free-of-charge, that looks explicitly at patterns of disclosure and specifically moves beyond looking at disclosure as an individual behavior and looks more broadly at how social-structural factors are tied to disclosure of HIV. Nearly three quarters of LISA participants (73.4 %) who had one or more new sexual partners in the last 6 months reported always disclosing their HIV-positive status to their sexual partners. The factors associated with not disclosing included being a gay or bisexual man, being a woman, having sex with a stranger, having sex without a condom, having sex with five or more partners, and not being on ART at the time of the interview. When our analysis focused on women more specifically, one additional variable, willingness to have sex without a condom with a partner who is HIV-positive, was also a significant predictor of non-disclosure. Gay and bisexual men were more likely to not disclose if they had sex with two or more partners and did not always use condoms.

The overall rate of disclosure reported here is slightly higher than other similar studies documented in the literature [21, 32–35]. In a multi-ethnic study conducted by Stein et al. [21], 60 % of all HIV-positive individuals disclosed their positive status to all of their partners. Another study examining HIV serostatus disclosure in 266 sexually active HIV-positive persons found that 41 % of participants had not disclosed their HIV serostatus to their last sex partner [34]. The rate of disclosure may have been higher in our sample due to the harsh Canadian criminalization of non-disclosure relative to other jurisdictions.

Certain trends that emerged in our study were found to be consistent with previous literature. In one large US study, bisexual and gay men were less likely to disclose their serostatus than heterosexual men and women, consistent with our findings [33]. This finding has at least in part been explained previously by the perceived social stigma gay and bisexual men feel surrounds HIV and AIDS, and the link between this social stigma and negative attitudes towards homosexuals and bisexuals [24]. While Marks and Crepaz [14] found that prevalence of safer sex did not differ between those who always disclosed and those who did not, another study found that, not using condoms was associated with non-disclosure [33].

Women and Disclosure

Although, the rate of disclosure for this population is relatively high, we found that women are less likely to disclose than heterosexual men, in contrast with other studies which state that women are more likely to disclose than men [20, 21]. This may be partly due to the fact that many of the women in the study are considered marginalized; generally women with low incomes and little education may not have the social power necessary to safely disclose. This is corroborated by the work of Vyavaharker et al. [36], which demonstrates that certain social contexts inhibit women’s ability to disclose their HIV status such as physical and sexual violence or having a history of drug use [35]. Research in Ontario, Canada found that women experience multi-leveled discrimination and stigma, which directly impacts their ability to cope and engage in healthy strategies, which may include self-disclosure [15]. Women who are marginalized are more likely to experience physical abuse following their diagnosis [33, 37, 38]. This fear of physical retribution may help explain why, in our study, sexual practices that lead to an increased vulnerability to HIV were found to be associated with not disclosing. A study investigating criteria for disclosing found that women were more likely to disclose to a partner they were close with, that they had a good relationship with, and was confident they would keep their HIV status confidential [39]. Women with multiple new sexual partners may not be provided with the emotional support or stability necessary for serostatus disclosure.

Gay and Bisexual Men and Disclosure

High-risk sexual behaviors, including sex with five or more partners, sex with strangers, and sex without a condom, were associated with non-disclosure among gay and bisexual men in our study, which is corroborated by previous published literature [4, 19, 21, 31, 40–43]. The disclosure rate noted for gay and bisexual men is lower than that of heterosexual men, which is also consistent with the published literature [2, 20, 21]. While men may be more likely than women to disclose to regular sexual partners, specific patterns emerge around sexual orientation and relationships structure [24, 43]. In one study of HIV-positive men, 11 % did not disclose to their primary partner whereas 66 % did not disclose to a non-primary sex partner [24]. We have demonstrated that men with five or more partners are less likely to disclose which is quite intuitive as individuals with more sexual partners may have more of an opportunity to not disclose.

Gay and bisexual men continue to be a socially marginalized and highly stigmatized population and placing the responsibility of disclosure solely on the positive person may further marginalize this population [4, 40]. Research suggests that there are consequences associating with disclosing such as fear of social rejection and isolation, stigmatization, and criminalization [19, 26, 32, 40, 41]. This stigma and marginalization may be unique to gay and bisexual men, which is why we are seeing lower rates of disclosure compared to heterosexual men. Strategies for gay and bisexual men may be to disclose to those individuals who they feel a connection or trust with [15, 44]. Recognizing these structural and social variables is essential in not only de-stigmatizing HIV-disclosure but also for minimizing the rhetoric of gay and bisexual men as an inherently risky population.

Limitations

The reader should be aware of the limitations in our study. Although the sample size is both large and diverse, the LISA cohort is not representative of all HIV-positive people in BC. As noted in the methods section, injection drug users, people of Aboriginal descent, and women were oversampled to sufficiently power comparisons between groups. Additionally, while men were divided into two groups—heterosexual men and gay and bisexual men—due to the small number of self-reported lesbians and bisexual females in the LISA cohort, all women were grouped together in the statistical analysis. The financial honorarium offered to participants could have led to the oversampling of individuals of low socio-economic status. The study only includes individuals who have been or were currently on ART at the time of the interview and thus excludes those HIV-positive individuals who never went on therapy during the study period. With respect to the chosen analysis, proportional odds and multinomial models were attempted to make use of the ordinal data, but there was much agreement between the various levels of non-disclosure. There would be some information to be gained through not dichotomizing the data, but it appeared to be minimal. Finally, data gathered through the interviewer-administered questionnaire, may be subject to both recall and social desirability bias. Considering the current legal context surrounding disclosure and HIV in BC, it is also possible that prevalence of disclosure may be over reported.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results suggest that nearly three-quarters of HIV-positive men and women in the study disclose their HIV-status to new sexual partners. Gay and bisexual men and women are less likely to disclose their HIV-positive status to new sexual partners than heterosexual men. Furthermore, gay or bisexual men and women who do not disclose are more likely to have multiple new sex partners and engage in practices that lead to an increased vulnerability to HIV, suggesting that the support and trust necessary for disclosure is not available in those circumstances and that there are more opportunities to not disclose than individuals with fewer partners.

Ultimately, disclosing one’s positive status cannot be understood without considering the social and environmental context within which sexual relationships and behaviors are negotiated [19]. Both HIV-related stigma and the historical and contemporary marginalization of certain populations due to race, gender and sexual orientation are important elements of the overall context and environment, which need to be considered. As non-disclosure has been associated with higher rates of HIV transmission [1], future strategies that aim to encourage disclosure should focus on the structural issues that may inhibit HIV-positive people from safely disclosing. In Canada, the criminalization of HIV-positive individuals who do not disclosure their status is a pertinent and controversial issue and has created an environment where non-disclosers are not only at an increased risk for violence, exclusion and discrimination, but criminal prosecution. We believe that patterns of disclosure and non-disclosure largely reflect the unique circumstances stigmatized and marginalized populations are expected to disclose in. Placing the responsibility of discussing sexual risk solely on HIV-positive people will continue to marginalize, stigmatize and potentially offset significant movements in treatment and prevention of HIV.

References

Pinkerton S, Galletly C. Reducing HIV transmission risk by increasing serostatus disclosure: a mathematical modeling analysis. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:698–705.

Chen S, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse between potentially HIV-serodiscordant men who have sex with men, San Francisco. JAIDS. 2003;33:166–70.

Golden M, et al. Importance of sex partners HIV status in HIV risk assessment among men who have sex with men. JAIDS. 2004;36:734–42.

Klitzman R, et al. It’s not just what you say: relationship of HIV disclosure and risk reduction among MSM in the post-HAART era. AIDS Care. 2007;19:749–56.

Simone J, Pantalone D. Secrets and safety in the age of AIDS: Does HIV disclosure lead to safer sex? Int AIDS Soc USA. 2004;4:109–18.

Bird J, Fingerhurt D, McKirnan. Ethnic differences in HIV-disclosure and sexual risk. AIDS Care. 2011;23:444–8.

King R, et al. Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:232–43.

Serovich J. A test of two HIV disclosure theories. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001;13(4):355–64.

Lovejoy N. AIDS: impact on the gay man’s homosexual and heterosexual families. Marriage Fam Rev. 1990;14:285–316.

Macklin E. AIDS: implications for families. Fam Relat. 1998;37:141–9.

Eustace R, Ilagan P. HIV disclosure among HIV positive individuals: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:2094–103.

Petrak J, et al. Factors associated with self-disclosure of HIV serostatus to significant others. British J Health Psychol. 2001;6:69–79.

Dempsey A, et al. Patterns of disclosure among youth who are HIV-positive: a multisite study. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:315–7.

Marks G, Crepaz N. HIV-positive men’s sexual practices in the context of self-disclosure of HIV status. JAIDS. 2001;27:79–85.

Siegel K, Lune H, Meyer I. Stigma management among gay-bisexual men with HIV/AIDS. Qual Sociol. 1998;21(1):3–24.

Logie C, et al. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation, and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2011;8:11.

Overstreet N, et al. Internalized stigma and HIV status disclosure among HIV-positive black men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2013;25(4):466–71.

C.H.A.L. Network, HIV Disclosure and the Criminal Law in Canada: Responding to the Media and the Public. Briefing paper, 2003. 30 Oct 2003.

Kalichman S, et al. Stress, social support, and HIV-status disclosure to family and friends among HIV-positive men and women. J Behav Med. 2003;26(4):315–32.

Olley B, Seedat S, Stein D. Self-disclosure of HIV serostatus in recently diagnosed patients with HIV in South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8:71–6.

Stein M, et al. Sexual ethics. Disclosure of HIV-positive status to partners. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:253–7.

Gorbach P, et al. Don’t ask, don’t tell: patterns of HIV disclosure among HIV positive men who have sex with men with recent STI practicing high-risk behavior in Los Angeles and Seattle. Sex Trans Infect. 2004;80:512–7.

McLean J, et al. Regular partners and risky behavior: why do gay men have unprotected intercourse? AIDS Care. 1994;6:331–41.

Obermeyer C, Baijal P, Pegurri E. Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: a review. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1011–22.

Hart J, et al. Effect of directly observed therapy for highly active antiretroviral therapy on virologic, immunologic, and adherence outcomes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. JAIDS. 2010;54:167–79.

Pryzbyla S, et al. Serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV: examining the roles of partner characteristics and stigma. AIDS Care. 2013;25(5):566–72.

Derlega V, et al. Perceived HIV-related stigma and HIV disclosure to relationship partners after finding out about the seropositive diagnosis. J Health Psychol. 2002;7:415–32.

Wolitski R, et al. HIV serostatus disclosure among gay and bisexual men in four American cities: general patterns and relation to sexual practices. AIDS Care. 1998;10(5):599–610.

Thompson M, Aberg JA, Cahn P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the international AIDS society-USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304(3):13.

Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. Inst Stat Math. 1974;19:7160723.

Lin D, Wei L, Wing Z. Model-checking techniques based on cumulative residuals. Biometrics. 2002;58:1–12.

Niccolai L, et al. Disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners: predictors and temporal patterns. Sex Trans Dis. 1999;26:281–5.

Ciccarone D, et al. Sex without disclosure of positive HIV serostatus in a US probability sample of persons receiving medical care for HIV infection. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:949–54.

Kalichman S, Nachimson D. Self-efficacy and disclosure of HIV-positive serostatus to sex partners. Health Psychol. 1999;18(3):281–7.

Gielen A, et al. Women’s lives after an HIV-positive diagnosis: disclosure and violence. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:111–20.

Vyavaharkar M, et al. HIV-disclosure, social support, and depression among HIV-infected African American women living in the rural Southeastern United States. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23:78–90.

Gielen A, et al. Women living with HIV: disclosure, violence, and social support. J Urban Health. 2000;77(3):480–91.

Gielsen A, et al. Women’s lives after an HIV-positive diagnosis: disclosure & violence. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4(2):111–20.

Sowell R, et al. Disclosure of HIV infection: how do women decide to tell? Health Educ Res. 2003;18(1):32–44.

Serovich J, et al. An intervention to assist men who have sex with men disclose their serostatus to casual sex partners: results from a pilot study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:207–19.

Klitzman R. Self-disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners: a qualitative study of issues faced by gay men. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 1999;3(2):39–49.

Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson B. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1266–75.

Parsons J, et al. Consistent, inconsistent, and non-disclosure to casual sexual partners among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2005;19(1):s87–97.

Schnell D, Higgins D, Wilson R. Men’s disclosure of HIV test results to male primary sex partners. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(12):1675–6.

Acknowledgments

The LISA research team is thankful for the cooperation of our various research sites. We are inspired by their amazing dedication to their clients and the communities they serve. We would especially like to thank the participants of the LISA study who trust us with sensitive and intimate information and share their stories in hopes of supporting research projects that will make a difference in their communities. We respectfully listen and interpret their experiences and hope that we are doing them justice. We are also grateful for the contributions of the LISA Community Advisory Committee: Terry Howard, Rosa Jamal, Isabella Kirchner, Sandy Lambert, Kecia Larkin, Steve Levine, Melissa Medjuck, Stacie Migwans, Sam Mohan, Lori Montgomery, Glyn Townson, Michelle Webb, Sarah White; and Study Co-Investigators: Dr. Rolando Barrios, Dr. David Burdge, Dr. Marianne Harris, Dr. David Henderson, Dr. Thomas Kerr, Dr. Julio S.G. Montaner, Dr. Thomas Patterson, Dr. Eric Roth, Dr. Mark Tyndall, Dr. Brian Willoughby, and Dr. Evan Wood. Finally, we thank colleagues who have provided additional assistance with the dataset and manuscript: David Milan, Dragan Lesovski, Anya Shen, and Svetlana Draskovic.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Robert Hogg has held grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research National Health Research Development Program, and Health Canada. He has also received funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Merck Frosst Laboratories for participating in continued medical education programmes. Dr. Julio Montaner has received grants from Abbott, Biolytical, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck and ViiV Healthcare. He is also is supported by the Ministry of Health Services and the Ministry of Healthy Living and Sport, from the Province of British Columbia; through a Knowledge Translation Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); and through an Avant-Garde Award (No. 1DP1DA026182-01) from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, at the US National Institutes of Health. He has also received support from the International AIDS Society, United Nations AIDS Program, World Health Organization, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health Research-Office of AIDS Research, National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases, The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPfAR), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, French National Agency for Research on AIDS & Viral Hepatitis (ANRS), Public Health Agency of Canada. He has academic partnerships with the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, Providence Health Care and Vancouver Coastal Health. This study was supported by a fund received from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Grant number 53396).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hirsch Allen, A.J., Forrest, J.I., Kanters, S. et al. Factors Associated with Disclosure of HIV Status Among a Cohort of Individuals on Antiretroviral Therapy in British Columbia, Canada. AIDS Behav 18, 1014–1026 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0623-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0623-9