Abstract

There is little or no data examining the association between either pain or the use or misuse of opioid analgesic with adherence to antiretroviral medications (ARVs) among HIV-infected adults. We interviewed a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults prescribed antiretroviral medications (ARVs) quarterly to examine the association between (1) pain, (2) receipt of opioid analgesics, and (3) opioid analgesic misuse with self-reported ARV adherence. Of 281 participants, most (82.5 %) reported severe or moderate pain, half (52.4 %) received a prescription for opioids, and one quarter (24.6 %) misused opioid analgesics. Most (71.9 %) reported >90 % ARV adherence. In a GEE model, neither pain (unadjusted OR 1.14, CI 0.90–1.45) nor prescription of opioid analgesics (unadjusted OR 1.11, CI 0.84–1.49) were significantly associated with ARV adherence. Misuse of opioid analgesics was associated with incomplete adherence (AOR 1.42, CI 1.09–1.86). Individuals who misuse opioid analgesics, like those who use illicit substances, may have difficulty adhering to medication regimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Pain is prevalent among HIV-infected individuals and it worsens with progression of HIV [1–8]. Use of opioid analgesics for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain remains controversial because of the limited evidence for its efficacy and concerns about the potential for misuse [9–12]. Identifying individuals at risk for opioid analgesic misuse is challenging [13].

Predictors of opioid analgesic misuse and pain, such as illicit substance use and depression, are also associated with decreased ARV adherence [14–21]. Pain is associated with decreased medication adherence among individuals with chronic medical conditions other than HIV infection [22, 23]. Prior studies among HIV-infected individuals have not demonstrated a significant association between pain and ARV adherence; however, these studies were small, cross sectional, had a narrow sampling of participants (e.g. from a single methadone or neurology clinic), and did not adjust for other variables known to be associated with decreased adherence, such as substance abuse and depression [19, 24, 25].

We found no studies examining the association of either taking prescribed, or misusing, opioid analgesics with medication adherence among HIV or non-HIV infected individuals. Opioid-related substance use disorders are associated with decreased ARV adherence, and treatment of opioid use disorders with methadone or buprenorphine improves ARV adherence among HIV-infected individuals [26–28].

We examined whether pain, opioid analgesic use, and opioid analgesic misuse were associated with self-reported ARV adherence in a cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. We hypothesized that increased pain severity and the misuse of opioid analgesics would be associated with incomplete antiretroviral adherence, while appropriately using prescribed opioid analgesics would be associated with optimal adherence.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Design

Pain study participants were enrolled from the Research in Access to Care in the Homeless (REACH) cohort, which consisted of individuals recruited using probability sampling from homeless shelters, free meal programs, and single room occupancy hotels who tested positive for HIV [29]. We attempted to recruit all REACH cohort members who came for a quarterly REACH follow-up interview from September 2007 thru June 2008 (n = 337) into the Pain Study, regardless of current pain status or opioid analgesic use. Of REACH cohort members active at the time, 87.8 % (296) participated in the Pain Study. All participants reporting an ARV regimen at any visit were included in our analysis (n = 258). For the purposes of our analysis, follow up begins with the first visit at which subjects reported being prescribed ARVs and continues through all subsequent visits.

REACH study visits involved a 45-min structured interview that assessed demographics, health status, depression, HIV medication use and adherence, recent illicit substance use, alcohol use, housing status, and recent incarceration. At baseline, and 7 quarterly follow-up visits, participants completed the Pain Study questionnaire, a 45-min structured interview conducted by trained interviewers about pain and use and misuse of analgesic medications. To minimize under-reporting of stigmatized behavior, participants self-administered questions about opioid analgesic misuse behavior using Audio Computer-Assisted Self Interview (ACASI) technology [30–33]

All study procedures took place at the Tenderloin Clinical Research Center (TCRC), a University-affiliated Clinical Research Center associated with the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Clinical and Translational Science Institute. All participants provided written and informed consent prior to participation. We gave each participant modest reimbursement for their participation. We received a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Measurement of Adherence

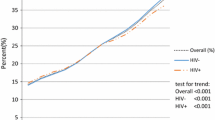

We assessed adherence at each study visit by self-report of percentage of prescribed doses taken in the past 7 days. For participants not reporting taking ARVs at subsequent visits, we categorized them as having zero adherence. We further categorized adherence as ≥90 % versus <90 % adherence; 90–95 % adherence is the optimal minimal adherence for virologic control [34–36].

Measurement of Pain

At each interview, we assessed worst pain severity during the prior week using a 0–10 numeric rating scale, based on the modified Brief Pain Inventory [37–39]. We categorized responses of 1–4 as mild pain, 5–6 as moderate pain, and ≥7 as severe pain [40, 41].

Opioid Analgesic Prescriptions

At each quarterly interview, we asked participants if they took opioid analgesics prescribed by a health care provider in the past 90 days. If they did, we asked them to identify the opioid analgesic, dose, and schedule from a picture of pills representing all opioid analgesics on the market. Medications that were formulated for sustained release, such as oxycodone controlled release and morphine sulfate controlled release, were classified as long-acting; other opioid analgesics were classified as short-acting. We converted the total dose of medication to oral morphine equivalent doses and reported the participants’ total average daily dose [42, 43].

Opioid Analgesic Misuse

We created a global variable of opioid analgesic misuse using participant ACASI responses to a series of yes/no questions about past-90-day opioid analgesic behavior. For each quarterly interview, we coded participants as reporting opioid analgesic misuse if they endorsed one or more of the following: using opioid analgesics to get high, altering the prescribed route of administration for transdermal or oral medications, selling of opioids, borrowing of opioids, exchanging opioids for sex or illicit drugs, attempting to forge a prescription for opioid analgesics, stealing opioids from another person or a pharmacy, hospital or clinic, and buying opioids without a prescription.

Depression

We assessed depressive symptoms using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and categorized scores of 0–13 as mild depression, 14–28 as moderate depression, and above 28 as severe depression [44]. In the multivariate model, we analyzed BDI score as a continuous variable.

Illicit Substance and Alcohol Use

We assessed current use of illicit drugs and alcohol at each quarterly interview. We categorized participants as current illicit substance users (versus not) based on self-reported use of cocaine, methamphetamine, and/or heroin in the past 90 days. We asked participants the average number of drinks per day on a typical day of drinking, in which one drink was defined as a 12 oz. can of beer, a 5 oz. glass of wine, or a 1.5 oz. drink of liquor. We defined problem drinking among participants if they consumed an average of >2 drinks per day (men) >1 drink per day (women) during the previous 30 days [45].

Health Status

We classified health as poor or fair versus good, very good or excellent based on participant self-report.

Statistical Analysis

Perceived general health and BDI score were missing for 7 and 5 observations, respectively. No other predictor variable had more than one missing observation. A total of 1,661 interviews were available for the 258 subjects. The mean number of interviews was 6.44 and 140 (54.3 %) subjects received all 8 pain interviews.

Odds ratios were calculated using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) with logit link. The exchangeable, m-dependent (with m = 2, 4 and 6), and auto-regressive structures were evaluated using the quasilikelihood under independence criterion (QIC) statistic, and the auto-regressive structure was selected based on this criterion. Predictors with a bivariate p value of 0.20 or less were included in multivariate models, which were then reduced using backward elimination until only predictors with p-value of 0.05 or less remained. We performed the analysis using SAS software (version 9.2).

Results

Of the 296 participants initially enrolled in the Pain Study, 258 participants reported taking ARVs at any visit during the Pain Study. At the baseline interview, participants were predominantly male (73.3 %) and African-American or White (39.9 % and 39.5 %, respectively), with a mean age of 48 (Table 1). A quarter of participants (27.1 %) reported moderate or severe depression, and 37.6 % rated their health status as poor or fair. Participants reported cocaine use (22.5 %), methamphetamine use (16.7 %), problem alcohol use (7.0 %), and heroin use (5.4 %) in the preceding 90 days.

At the baseline interview, most participants reported experiencing moderate (34.1 %) or severe (47.7 %) pain in the preceding week. Over half of participants (53.1 %) reported receipt of opioid analgesics prescribed by a health care provider in the past 90 days. Of those taking prescribed opioid analgesics, 34.7 % took more than 100 mg/day of oral morphine equivalent dose. One fifth of participants (20.5 %) reported opioid analgesic misuse in the preceding 90 days. Most participants (78.3 %) reported ≥90 % adherence to ARV therapy (Table 1). Subsequent visits in which participants who initially reported taking ARVs reported no longer receiving ARVs occurred for 103 (6.2 %) visits.

In a GEE analysis adjusting for age, education, homelessness, self-reported health status, depression, and substance use, neither severe pain (unadjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.37, CI 1.02–1.85) nor receiving prescribed opioid analgesics (OR 1.40 CI 0.99–1.97) was associated with incomplete ARV adherence (Table 2). Opioid analgesic misuse was independently associated with an increased odds of incomplete adherence [Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.47, CI 1.06–2.03], as was illicit substance use (AOR 2.10, CI 1.53–2.87) (Table 2). Other variables associated with increased odds of incomplete adherence in the adjusted analysis were homelessness for more than one consecutive year (AOR 1.67, CI 1.07–2.59), depression (AOR 1.02, CI 1.01–1.04) and poor or fair self-rated health (AOR 1.49, CI 1.14–1.97).

Discussion

In a cohort of indigent, HIV-infected adults on ARV therapy, we found a high prevalence of optimal ARV adherence. Neither pain nor receipt of prescribed opioid analgesics was associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Opioid analgesic misuse was associated with a 47 % increased odds of incomplete adherence.

Use of prescribed opioid analgesics was not associated with ARV adherence, but misuse of opioid analgesics was significantly associated with incomplete adherence after adjustment for other substance use disorders. Opioid analgesic misuse likely represents a similar, but distinct, phenomenon as illicit substance use, in which individuals’ priorities are focused on obtaining and using the desired substance at the expense of social, occupational, and personal obligations, including health maintenance [46]. HIV-infected adults with co-morbid substance abuse disorders are less likely to follow-up and remain in care, and are more likely to have ARV treatment interruptions [47, 48].

Individuals misusing opioid analgesics may benefit from interventions that are successful in improving adherence among HIV-infected adults with a history of substance use, such as opioid substitution therapy and directly observed therapy for ARVs [49–52]. Case management can assist with coordination of social, mental health, and medical services, as well as linkage to substance abuse treatment and adherence to ARVs [52, 53]. Health care provider knowledge of opioid analgesic misuse should trigger an assessment of ARV adherence among HIV-infected individuals, and vice versa, with appropriate referral to services.

In our unadjusted analysis, severe pain was associated with decreased ARV adherence, but this association was not significant in the multivariate analysis. We have confirmed the negative findings of prior studies demonstrating no association between pain and ARV adherence with a larger cohort of HIV-infected individuals followed longitudinally while considering many potential confounders, such as illicit substance use and depression [19, 24, 25, 40]. Substance use and depression are associated with both pain and decreased medication adherence [54–56]. These factors likely confound the association of pain and medication adherence and were not controlled for in prior studies that demonstrated an association between pain and medication adherence among non-HIV-infected individuals [22, 23].

Receiving prescribed long acting opioid analgesics was not associated with decreased adherence. Opioids have not consistently demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain among HIV-infected adults, and there is no clear data that use of opioid analgesics improves self-efficacy or functional status in HIV-infected and uninfected adults [9, 57, 58]. Many providers believe that prescribing of opioids will improve patients’ quality of life [59]. Treating pain with opioid analgesics in an effort to promote ARV adherence is not supported by our findings.

Participants who were homeless for at least 1 year were more likely to have decreased ARV adherence, consistent with prior studies looking at homelessness and ARV adherence [28, 60]. The association between poor or fair self-reported health status and decreased ARV adherence is consistent with prior findings demonstrating that lower self-rated health is associated with lower CD4 cell counts and later ARV initiation [61].

Our study has several limitations. We collected misuse and adherence data by self-report, though we minimized bias and consequent underreporting of opioid misuse behaviors with the use of ACASI software. Prior studies within this sample found that self-report generally overestimates adherence, but correlates with electronic pill count monitoring and unannounced pill count measures [34, 62–64].

Our finding that opioid analgesic misuse increases the odds of incomplete ARV adherence warrants further exploration. Research into engagement in care, barriers to adherence, and self-efficacy among participants misusing opioid analgesics may further elucidate the association between opioid analgesic misuse and ARV adherence. In patients with pain and incomplete ARV adherence, treatment of pain may not improve adherence, but evaluation and management of co-occurring substance use disorders and depression might.

References

Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Passik SD, Hewitt D, Thaler H, et al. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. I: Pain characteristics and medical correlates. Pain. 1996;68(2–3):315–21.

Breitbart W, Rosenfeld BD, Passik SD, McDonald MV, Thaler H, Portenoy RK. The undertreatment of pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. Pain. 1996;65(2–3):243–9.

Larue F, Fontaine A, Colleau SM. Underestimation and undertreatment of pain in HIV disease: multicentre study. BMJ. 1997;314(7073):23–8.

Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Passik SD, Thaler H, Portenoy RK. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. II: Impact of pain on psychological functioning and quality of life. Pain. 1996;68(2–3):323–8.

Singer EJ, Zorilla C, Fahy-Chandon B, Chi S, Syndulko K, Tourtellotte WW. Painful symptoms reported by ambulatory HIV-infected men in a longitudinal study. Pain. 1993;54(1):15–9.

Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization Study in Primary Care. JAMA. 1998;280(2):147–51.

Harding R, Easterbrook P, Dinat N, Higginson IJ. Pain and symptom control in HIV disease: under-researched and poorly managed. Clin Infect Dis. [Comment Letter]. 2005;40(3):491–2.

Lee KA, Gay C, Portillo CJ, Coggins T, Davis H, Pullinger CR, et al. Symptom experience in HIV-infected adults: a function of demographic and clinical characteristics. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(6):882–93.

Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, Coates VH, Wiffen PJ, Akafomo C, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(1):CD006605.

Ballantyne JC. Opioids for chronic nonterminal pain. South Med J. 2006;99(11):1245–55.

Ballantyne JC, Mao J. Opioid therapy for chronic pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(20):1943–53.

Chou R, Ballantyne JC, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Miaskowski C. Research gaps on use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain: findings from a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2009;10(2):147–59.

Turk DC, Swanson KS, Gatchel RJ. Predicting opioid misuse by chronic pain patients: a systematic review and literature synthesis. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):497–508.

Ives TJ, Chelminski PR, Hammett-Stabler CA, Malone RM, Perhac JS, Potisek NM, et al. Predictors of opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain: a prospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:46.

Michna E, Ross EL, Hynes WL, Nedeljkovic SS, Soumekh S, Janfaza D, et al. Predicting aberrant drug behavior in patients treated for chronic pain: importance of abuse history. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(3):250–8.

Vijayaraghavan M, Penko J, Guzman D, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Primary care providers’ judgments of opioid analgesic misuse in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(4):412–8.

Edlund MJ, Steffick D, Hudson T, Harris KM, Sullivan M. Risk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2007;129(3):355–62.

Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG). AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–66.

Gordillo V, del Amo J, Soriano V, Gonzalez-Lahoz J. Sociodemographic and psychological variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13(13):1763–9.

Haubrich RH, Little SJ, Currier JS, Forthal DN, Kemper CA, Beall GN, et al. The value of patient-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in predicting virologic and immunologic response. California Collaborative Treatment Group. AIDS. 1999;13(9):1099–107.

Morasco BJ, Turk DC, Donovan DM, Dobscha SK. Risk for prescription opioid misuse among patients with a history of substance use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. doi 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.032.

Krein SL, Heisler M, Piette JD, Butchart A, Kerr EA. Overcoming the influence of chronic pain on older patients’ difficulty with recommended self-management activities. Gerontologist. 2007;47(1):61–8.

Krein SL, Heisler M, Piette JD, Makki F, Kerr EA. The effect of chronic pain on diabetes patients’ self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(1):65–70.

Lucey BP, Clifford DB, Creighton J, Edwards RR, McArthur JC, Haythornthwaite J. Relationship of depression and catastrophizing to pain, disability, and medication adherence in patients with HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. AIDS Care. 2011;23(8):921–8.

Cervia LD, McGowan JP, Weseley AJ. Clinical and demographic variables related to pain in HIV-infected individuals treated with effective, combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Pain Med. 2010;11(4):498–503.

Roux P, Carrieri MP, Villes V, Dellamonica P, Poizot-Martin I, Ravaux I, et al. The impact of methadone or buprenorphine treatment and ongoing injection on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence: evidence from the MANIF2000 cohort study. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1828–36.

Metzger DS, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. Drug treatment as HIV prevention: a research update. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S32–6.

Palepu A, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Zhang R, Wood E. Homelessness and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among a cohort of HIV-infected injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2011;88(3):545–55.

Robertson MJ, Clark RA, Charlebois ED, Tulsky J, Long HL, Bangsberg DR, et al. HIV seroprevalence among homeless and marginally housed adults in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1207–17.

Rogers SM, Willis G, Al-Tayyib A, Villarroel MA, Turner CF, Ganapathi L, et al. Audio computer assisted interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviours in a clinic population. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(6):501–7.

Kurth AE, Martin DP, Golden MR, Weiss NS, Heagerty PJ, Spielberg F, et al. A comparison between audio computer-assisted self-interviews and clinician interviews for obtaining the sexual history. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(12):719–26.

Macalino GE, Celentano DD, Latkin C, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D. Risk behaviors by audio computer-assisted self-interviews among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative injection drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(5):367–78.

Murphy DA, Durako S, Muenz LR, Wilson CM. Marijuana use among HIV-positive and high-risk adolescents: a comparison of self-report through audio computer-assisted self-administered interviewing and urinalysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(9):805–13.

Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14(4):357–66.

Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30.

Mannheimer S, Friedland G, Matts J, Child C, Chesney M. The consistency of adherence to antiretroviral therapy predicts biologic outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(8):1115–21.

Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–38.

Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):309–18.

Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Donaghy KB, Portenoy RK. Pain and Aberrant Drug-Related Behaviors in Medically Ill Patients With and Without Histories of Substance Abuse. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(2):173–81.

Miaskowski C, Penko JM, Guzman D, Mattson JE, Bangsberg DR, Kushel MB. Occurrence and characteristics of chronic pain in a community-based cohort of indigent adults living with HIV infection. J Pain. 2011;12(9):1004–16.

Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, Edwards KR, Cleeland CS. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61(2):277–84.

Korff MV, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, Boudreau D, Campbell C, Merrill J, et al. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):521–7.

Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Trends in use of opioids for non-cancer pain conditions 2000–2005 in commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain. 2008;138(2):440–9.

Storch EA, Roberti JW, Roth DA. Factor structure, concurrent validity, and internal consistency of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition in a sample of college students. Depress Anxiety. 2004;19(3):187–9.

US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. In: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Chapter 9—Alcoholic Beverages. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2005. p. 43–6.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—fourth edition (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Kavasery R, Galai N, Astemborski J, Lucas GM, Celentano DD, Kirk GD, et al. Nonstructured treatment interruptions among injection drug users in Baltimore, MD. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(4):360–6.

Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC Jr, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(11):1493–9.

Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Joy R, Kerr T, Wood E, Press N, et al. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: the role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84(2):188–94.

Moatti JP, Carrieri MP, Spire B, Gastaut JA, Cassuto JP, Moreau J. Adherence to HAART in French HIV-infected injecting drug users: the contribution of buprenorphine drug maintenance treatment. The Manif 2000 study group. AIDS. 2000;14(2):151–5.

Altice FL, Maru DS, Bruce RD, Springer SA, Friedland GH. Superiority of directly administered antiretroviral therapy over self-administered therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(6):770–8.

Gonzalez A, Barinas J, O’Cleirigh C. Substance use: impact on adherence and HIV medical treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):223–34.

Kushel MB, Colfax G, Ragland K, Heineman A, Palacio H, Bangsberg DR. Case management is associated with improved antiretroviral adherence and CD4 + cell counts in homeless and marginally housed individuals with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(2):234–42.

Tsao JC, Stein JA, Ostrow D, Stall RD, Plankey MW. The mediating role of pain in substance use and depressive symptoms among Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) participants. Pain. 2011;152(12):2757–64.

Katon W, Russo J, Lin EH, Heckbert SR, Karter AJ, Williams LH, et al. Diabetes and poor disease control: is comorbid depression associated with poor medication adherence or lack of treatment intensification? Psychosom Med. 2009;71(9):965–72.

Bailey JE, Hajjar M, Shoib B, Tang J, Ray MM, Wan JY. Risk Factors Associated with Antihypertensive Medication Nonadherence in a Statewide Medicaid Population. Am J Med Sci. 2012 Aug 9.

Koeppe J, Armon C, Lyda K, Nielsen C, Johnson S. Ongoing pain despite aggressive opioid pain management among persons with HIV. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(3):190–8.

Koeppe J, Lyda K, Johnson S, Armon C. Variables associated with decreasing pain among persons living with human immunodeficiency virus: a longitudinal follow-up study. Clin J Pain. 2011. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318220199d.

Nwokeji ED, Rascati KL, Brown CM, Eisenberg A. Influences of attitudes on family physicians’ willingness to prescribe long-acting opioid analgesics for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Clin Ther. 2007;29(Suppl):2589–602.

Leaver CA, Bargh G, Dunn JR, Hwang SW. The effects of housing status on health-related outcomes in people living with HIV: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):85–100.

Souza Junior PR, Szwarcwald CL, Castilho EA. Self-rated health by HIV-infected individuals undergoing antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27(Suppl 1):S56–66.

Moss AR, Hahn JA, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Guzman D, Clark RA, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the homeless population in San Francisco: a prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(8):1190–8.

Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Chang CJ, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(8):1417–23.

Arnsten JH, Li X, Mizuno Y, Knowlton AR, Gourevitch MN, Handley K, et al. Factors associated with antiretroviral therapy adherence and medication errors among HIV-infected injection drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;1(46 Suppl 2):S64–71.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse R01DA022550, and a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health R01MH54907. This publication was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study or the preparation of the manuscript. Drs. Kushel and Jeevanjee had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jeevanjee, S., Penko, J., Guzman, D. et al. Opioid Analgesic Misuse is Associated with Incomplete Antiretroviral Adherence in a Cohort of HIV-Infected Indigent Adults in San Francisco. AIDS Behav 18, 1352–1358 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0619-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0619-5