Abstract

Home-based HIV testing and counseling (HBTC) has the potential to increase access to HIV testing. However, the extent to which HBTC programs successfully link HIV-positive individuals into clinical care remains unclear. To determine factors associated with early enrollment in HIV clinical care, adult residents (aged ≥13 years) in the Health and Demographic Surveillance System in Kisumu, Kenya were offered HBTC. All HIV-positive residents were referred to nearby HIV clinical care centers. Two to four months after HBTC, peer educators conducted home visits to consenting HIV-positive residents. Overall, 9,895 (82 %) of 12,035 residents accepted HBTC; 1,087 (11 %) were HIV-positive; and 737 (68 %) received home visits. Of those receiving home visits, 42 % reported HIV care attendance. Factors associated with care attendance included: having disclosed, living with someone attending HIV care, and wanting to seek care after diagnosis. Residents who reported their current health as excellent or who doubted their HBTC result were less likely to report care attendance. While findings indicate that HBTC was well-received in this setting, less than half of HIV-positive individuals reported current care attendance. Identification of effective strategies to increase early enrollment and retention in HIV clinical care is critical and will require coordination between testing and treatment program staff and systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Kenya, an East African country of 38.8 million people, an estimated 6.3 % of adults are living with HIV [1]. HIV prevalence is higher among women (8.0 %) than men (4.3 %). Among married couples, rates of HIV sero-discordance are high with an estimated 43 % of HIV-positive women and 44 % of HIV-positive men living with an HIV-negative partner [1]. However, most Kenyans remain unaware of their HIV status. In a recent national survey, only 58 % of women and 42 % of men aged 15–64 years reported that they had ever been tested for HIV in their lifetime and 31 % of HIV-positive individuals were unaware of their status [1].

Early identification of HIV-positive individuals through HIV testing and counseling (HTC) and linkage of these individuals to HIV care and treatment services reduces the morbidity and mortality experienced by the HIV-positive individual [2, 3] and the risk of transmission to HIV-negative partners [4–6]. The Government of Kenya has made the expansion of HTC services a national goal and aims to provide HIV testing to at least 80 % of all adolescents and adults by 2013 [7]. A variety of HIV testing approaches are being utilized to reach this goal including provider-initiated HTC offered as part of routine care in health facilities, community-based HIV testing services (both mobile and standalone clinics), and home-based HIV testing and counseling services (HBTC).

HBTC has the potential to increase access to HIV testing by eliminating the need for individuals to travel to a health facility or community center for HIV testing. HBTC promotes couples- and family-centered care and prevention by offering services at the household level to individuals, couples, and families and encouraging disclosure and support among couples and family members. By offering testing services to individuals not routinely accessing the health care system or who perceive themselves to be at low risk for HIV infection, HBTC provides the opportunity to identify asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals early in their infection and facilitate their enrollment and receipt of HIV clinical care and prevention services. However, the extent to which HBTC programs successfully link HIV-positive individuals into these services remains unclear.

In this study, we describe the HBTC coverage, acceptance, and HIV prevalence rates among adult residents of a longitudinal Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) in a rural area of Nyanza province, Kenya. We also describe characteristics associated with enrollment into HIV clinical care within two to four months after receiving an HIV diagnosis during HBTC.

Methods

Heath and Demographic Surveillance System

This study took place in Nyanza Province in western Kenya. Adult HIV prevalence is 13.9 %, the highest in Kenya, and HIV testing rates are low with only 34 % of adults reporting an HIV test within the past 12 months [1]. Since 2001, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) have maintained a HDSS in Nyanza province. Details of the surveillance activities conducted as part of the HDSS have been previously described [8]. In brief, regular household visits are conducted every 4 months to collect data on socio-demographic and health indicators for all household members including births, deaths, pregnancies, and migrations. Verbal autopsies are conducted with a primary caregiver within 4–6 months after notification of a resident death and then reviewed by clinicians who assign a probable cause of death. Bi-annual household socioeconomic and education status surveys are also conducted with each household. The positions of housing compounds, health facilities, and public transport roads are mapped annually with an estimated accuracy of ±1 m [9]. The HDSS also serves as a sampling frame or platform for the conduct of surveys and assorted research studies on a variety of illnesses including malaria and HIV.

Procedures for HBTC and Follow-up

From February 2008 to July 2009, trained counselors made three household visits to offer HBTC to all adult HDSS residents aged 13 years and older in the Asembo area of Nyanza Province. Prior to conducting HBTC, counselors obtained written informed consent from all adult participants that included permission to administer a survey on HIV testing experiences and sexual behaviors; to perform HIV testing and provide post-test counseling; and to link participant data to the larger HDSS dataset. In addition, all residents were informed that they might receive follow-up visits following HBTC for potential participation in various ongoing studies or follow-on programs as part of the consent process. This component of the consent avoided repeatedly re-consenting participants as well as minimizing unintentional disclosure of HIV status to other household members or community residents. Residents were free to decline HBTC and still be enrolled in the HDSS. Children 12 years and younger, were tested only if the biologic mother was known to be HIV-positive or deceased after consent was obtained from a primary caregiver. Individuals who self-reported HIV-positive status when offered HBTC were only retested at their request. All HIV testing was performed according to Kenyan Ministry of Health guidelines.

Residents who tested HIV-positive during HBTC were provided with a referral letter and a list of all nearby health facilities offering HIV care and treatment services. Residents were asked to indicate to the HBTC counselor their “preferred” facility for HIV care, and counselors received residents’ permission to have a facility-based peer educator from the preferred facility return to the household for a follow-up visit 2–4 months following HBTC.

Facility-based peer educators, who were HIV-positive and currently enrolled in HIV care and treatment at the facility, made three attempts to revisit homes of all HIV-positive adults who consented to a follow-up visit. Peer educators first asked residents to reconfirm both their HIV-positive status and their willingness to be re-contacted. Residents unwilling to do both were considered to have refused contact and were not interviewed.

Consenting residents were interviewed about their HBTC experience, HIV status disclosure, enrollment in HIV care, and their perceived health status. Stigma as a barrier to HIV care enrollment was assessed in two ways. First, all participants were asked whether they felt fear of stigma was a barrier to seeking HIV care among individuals in their community. In addition, residents who reported non-attendance in care were asked whether fear of stigma was a factor in their own decision not to seek HIV care. Residents who reported that they were currently enrolled in HIV care were asked about their health care experiences including any medications they were currently taking. Following the interview, peer educators answered residents’ questions about HIV and offered to facilitate entry into HIV clinical care services for any participant who was not yet enrolled.

Children who tested HIV-positive during HBTC were not interviewed by peer educators. However, mothers and caregivers of these children were asked whether the child was currently enrolled in HIV clinical care, and if not, reasons for non-enrollment in care. These findings are presented separately.

This study was reviewed and approved by the KEMRI Scientific Steering Committee and the CDC Institutional Review Board.

Data Management and Analysis

Data from paper-based forms were entered into Microsoft Access and exported into Stata 11.1 for analysis (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Information from HBTC and peer educator follow-up interviews were linked to the wider HDSS dataset using name (2 names), gender, age at enrolment (±5 years), residential information, and HDSS unique identification number. Information derived from the linked data included household socio-economic status [quintiles of all HDSS households ranging from 1 (poorest) to 5 (wealthiest)] and distance between household residence and nearest health facility offering HIV clinical care.

Descriptive statistics were computed for variables of interest overall and by gender. χ 2 and t tests were used to examine gender differences for all variables of interest. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were fit to explore the relationship between variables of interest and the outcome variable, self-reported current enrolment in HIV clinical care. The final multivariable model included potentially predictive (P < 0.20) characteristics for HIV care enrolment identified in univariable logistic regression models as well as forced inclusion of potential confounders including marital status, distance from household to nearest HIV clinic, time between HBTC and the follow-up interview, and being newly diagnosed with HIV as part of HBTC. Variables were considered significant with a P value less than 0.05. All regression models were adjusted using the generalized estimating equation (GEE) to account for clustering within households [10].

Results

HBTC Service Delivery

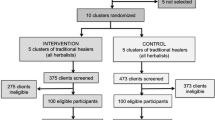

A schematic of HDSS residents who were offered and accepted HBTC and who received a follow-up visit by a peer educator is presented in Fig. 1. Overall, 76 % of eligible HDSS residents were approached by HBTC counselors. Individuals who were contacted at home and offered HBTC were more likely to be female (58 vs. 42 %, χ 2 = 185.4, P < 0.001) and older (mean age: 36.5 vs. 27.6, t = −31.9, P < 0.0001) than residents who were not contacted or offered HBTC. Among residents offered HBTC, 82 % agreed to complete the survey and receive HIV testing. HBTC uptake was higher among residents who were younger (mean age 35.8 vs. 39.5, t = 8.4, P < 0.0001) and had not been previously tested for HIV (67 vs. 32 %, χ 2 = 130.1, P < 0.0001). Although 44 % of residents reported being married and 53 % were sexually active, only 17 % of sexually active residents knew the HIV status of their partner. HIV prevalence among all HBTC residents was 11 % and was significantly higher among females than males (13 vs. 8 %, χ 2 = 53.5, P < 0.0001).

Adults Diagnosed as HIV-Positive During HBTC

Of the 1,087 adult HDSS residents who tested HIV-positive, 923 (85 %) were newly diagnosed during HBTC while the remaining 15 % were previously aware of their status. The mean age of HIV-positive residents was 36.6 years (SD 13.3) and 68 % were female. 943 (87 %) of HIV-positive residents consented to a follow-up visit by a peer educator, and peer educators contacted and interviewed 737 (78 %) of these residents (Fig. 1). Residents who completed a follow-up interview were significantly older (mean age: 37.8 vs. 33.9, t = −4.6, P = 0.0001) and more likely to be widowed (30 vs. 19 %, χ 2 = 24.4, P = 0.0001) than residents who did not complete a follow-up interview (Table 1).

Of the 206 originally consenting residents who did not receive a follow-up visit, 89 (43 %) had migrated out of the area, 70 (34 %) refused the follow-up visit, 27 (13 %) could not be reached, and 20 (10 %) had died. Reported causes of death among these 20 residents included: 15 (75 %) AIDS-related conditions, 4 (20 %) cancer, and 1 (5 %) hypertension. Among the 15 residents who died of an AIDS-related condition, 12 (80 %) had been previously unaware of their HIV status prior to HBTC. The mean length of time between diagnosis and death for patients with an AIDS-related condition was three months.

HBTC Experience and Disclosure

Among the 737 HIV-positive individuals who completed a follow-up interview, 70 % were women and over half (57 %) were married (Table 2). The mean length of time between HBTC and the follow-up interview was 3.5 months (SD 1.1 month). Compared to men, women were more likely to be younger (mean age 36.7 vs. 40.1, t = 3.2, P = 0.002) and widowed (38 vs. 10 %, χ 2 = 76.3, P = 0.0001). Men were more likely to be residing in a household with another HIV-positive individual (32 vs. 18 %, χ 2 = 16.6, P = 0.0001). Most (60 %) residents received HBTC individually with men and women equally as likely to report testing as an individual. However, women were more likely to be tested as part of a family (24 vs. 13 %, χ 2 = 20.6, P < 0.0001) while men were more likely to test as a couple (28 vs. 16 %, χ 2 = 20.6, P < 0.0001).

Satisfaction with HBTC service delivery was high (74 %). Residents reported feeling satisfied knowing their status (56 %), appreciated the privacy of testing in their own home (17 %), and the assistance with disclosure (13 %) provided through couples and family HIV testing. Fewer residents (20 %) reported feeling sad or shocked at the results while 14 % disbelieved their test result. Following HBTC, 55 % of residents had disclosed their HIV status to someone with males more likely to report disclosing to their spouse (49 vs. 33 %, χ 2 = 16.4, P = 0.0001). Residents who tested as part of a couple or family were significantly more likely to report disclosure than those who tested individually (93 and 73 vs. 37 %, respectively, χ 2 = 159.5, P < 0.0001).

Attendance in Care

The vast majority of residents interviewed (73 %) described their health as good or excellent, and less than half reported receipt of any medical care since HBTC. Overall, only 312 (42 %) HIV-positive residents reported current attendance in HIV clinical care (Table 2) following HBTC. Most residents (66 %) reported receiving HIV care at a facility that was less than 5 km from their residence (Fig. 2) and the distance to the nearest HIV care facility did not differ significantly between those individuals in care and those not in care (mean distance 1,728 vs. 1,700 m, t = −0.48, P = 0.63). The mean length of time between diagnosis and enrollment into care was 26.5 days (SD 87.6).

Most residents initiated HIV care alone (77 %) and traveled by foot to the HIV clinic (61 %). Almost all residents reported receiving cotrimoxazole and multivitamins (98 %), while 80 (26 %) were receiving antiretrovirals. Residents cited encouragement by an HBTC counselor (46 %) as one of the main reasons for seeking medical care, and 97 % perceived that HBTC facilitated their enrollment into medical care. Most residents (94 %) were attending their preferred health facility for HIV clinical services with proximity of the clinic to their residence cited by 66 % as the main reason for the selection.

Overall, 425 (58 %) HIV-positive residents reported that they were not currently attending HIV care at the follow-up interview. The two main reasons cited for non-attendance in care were feeling in good health (34 %) and disbelief of their HIV result (23 %). Disbelief of the HIV test result was significantly associated with reporting current health status as excellent (χ 2 = 11.0, P = 0.001). While stigma was mentioned by 76 % of residents as the main barrier inhibiting HIV-positive individuals in their community from seeking HIV care, only 17 % of residents who reported not attending HIV care cited fear of being stigmatized as a reason for their own non-attendance in care. Furthermore, fear of stigma was not related to failure to enroll in HIV care (χ 2 = 2.283, P = 0.13).

Overall, 685 children received HBTC; 51 (7 %) were identified as HIV-positive. Their mean age was 4.5 years (SD 3.7) and 57 % were female. Of the 39 (80 %) pediatric respondents with follow-up data available, only 40 % of children and 54 % of their mothers reported current attendance in HIV care. Maternal attendance in HIV care was not associated with the child’s attendance in care (χ 2 = 3.1, P = 0.077). The gender and age distribution of children enrolled in care did not differ significantly from children not in care. Main reasons cited for pediatric non-enrollment in care included: family/child not ready to seek treatment (37 %), child perceived to be healthy (16 %), disbelief of child’s HIV test result (16 %), and family/child chose to seek alternative sources of care (16 %).

In multivariable analysis (Table 3), significant correlates of attendance in HIV clinical care included: having disclosed HIV status (OR 2.10, 95 % CI 1.50, 2.94), living in a household with another individual attending HIV clinical care (OR 4.15, 95 % CI 1.76, 9.74), and wanting to seek medical care following the HIV diagnosis (OR 3.04, 95 % CI 1.58, 5.84). Residents who reported their current health status as good (OR 4.04, 95 % CI 2.23, 7.25), fair (OR 9.54, 95 % CI 4.52, 20.1), or poor (OR 3.46, 95 % CI 1.29, 9.27) were more likely to report care attendance than those who reported excellent health. Residents were less likely to report care attendance if they perceived the HBTC test result to be inaccurate (OR 0.12, 95 % CI 0.04, 0.32). Age, gender, marital status, being newly diagnosed with HIV, length of time between HBTC and the follow-up interview, and household proximity to an HIV care facility were included in the model but were not associated with current care attendance.

Discussion

HBTC was well-received by the community and increased individuals’ and families’ knowledge of HIV status. However, at 2–4 months after HBTC, only 42 % of HIV-positive individuals reported current attendance in HIV clinical care. This rate is lower than another study conducted in rural Kenya which found that 63 % of individuals diagnosed as HIV-positive during a community-based HIV testing program had enrolled in care within 3-months of diagnosis [11]. However, that study included peer navigators who facilitated enrollment into HIV care for individuals diagnosed as HIV-positive. In contrast, the rates of care enrollment observed in this HBTC study were much higher than the 28 and 36 % observed after mobile HTC campaigns in Ethiopia [12] and South Africa, respectively [13].

Factors significantly associated with care enrollment included disclosure, living in a household with another individual attending HIV clinical care, and reporting less than excellent health. Reasons for not enrolling in HIV clinical care were similar for both adults and children and included being in good health and disbelief of HIV test results. Demographic characteristics and proximity of the household to the nearest HIV care facility were not associated with enrollment. Furthermore, while stigma was mentioned by many residents as a factor inhibiting HIV-positive individuals in their community from seeking care, it was not significantly associated with actual non-enrollment in HIV care among HIV-positive HBTC residents.

Earlier studies identified distance and transport costs as main barriers to both enrollment and retention in care mainly through participant self-report [14–18]. By contrast, the GIS mapping data collected as part of the larger HDSS in this study, allowed us to uniformly calculate the distance from residence to health facility and conclude that distance was not significantly different between residents who were and were not currently enrolled in care. Since 2005, the Kenyan Ministry of Health has been decentralizing HIV care and treatment services to smaller health centers in order to improve access to these services. Our findings suggest that this decentralization of services has removed distance as a major barrier to care enrollment. Continued assessment will be needed to determine if decentralization will help retain patients in care by removing distance and transport costs as barriers to continued enrollment in HIV clinical care [19, 20].

Residents were less likely to enroll in HIV clinical care if they perceived their health to be excellent. This finding is similar to other studies that have also noted that patients wait to access care until after they have developed symptomatic disease [21–24]. In addition, our finding that disbelief of the HIV test result was negatively associated with care enrollment but positively associated with reporting current health as excellent suggests that individuals diagnosed before the onset of symptoms will most likely require additional education and counseling on the accuracy of the HIV test result to facilitate care enrollment. As late enrollment into treatment is associated with both early mortality [25, 26] and increased risk of HIV transmission to sex partner(s) [4–6], HIV counselors should educate all HIV-positive individuals on the health and prevention importance of seeking early HIV clinical care even if they are asymptomatic and perceive their health as excellent.

Disclosure and living in a household with another HIV-positive individual attending HIV care were both associated with current care enrollment among adults. While other studies have highlighted the importance of disclosure and family support in the uptake of and adherence to HIV care and treatment services [15, 27], this study used the household data collected as part of the larger HDSS to also identify the importance of having another family member in HIV care as a key predictor of HIV care enrollment. In addition to its importance in facilitating care enrollment, disclosure to sex partners is also important for prevention as it allows the couple to make decisions about condom use and other risk reduction strategies to prevent HIV transmission to uninfected partner(s) and children [28]. Future HBTC activities and other HTC efforts should continue to train counselors on how to perform family and couples HIV testing and counseling. Whenever possible, counselors should encourage individuals to test as couples or families to facilitate disclosure and subsequent enrollment into care. Given the importance of disclosure in both HIV care and prevention efforts, counselors should also discuss strategies for safe disclosure with individuals who test alone. Counselor-assisted disclosure may also be one option for individuals who do not feel comfortable disclosing on their own.

This study had a number of limitations. First, HIV prevalence was most likely underestimated in this population-based sample. HBTC service delivery missed younger residents and men who were more likely to be absent from the home. In addition, HIV-positive residents who already knew their HIV status might have been more likely to refuse HIV testing. Second, the results presented here do not represent the rates of engagement in care for all HIV-infected individuals or only persons newly diagnosed as HIV-infected in this population as self-reported HIV-positive individuals who refused HBTC were excluded, and both those newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals as well as those who already knew their status and chose to be re-tested were included. Moreover, as this study did not collect WHO staging or CD4 data for patients enrolled in HIV clinical care, we cannot assess ART eligibility or predictors of ART uptake in this population. However, our self-reported ART uptake findings appear to be consistent with those in the literature [29], and it is highly likely that a substantial proportion of our HBTC population did not yet qualify for ART [30]. Younger and single/never married HIV-positive residents were less likely to both consent to and receive a follow-up visit by a peer educator. Thus, the perceptions and experiences of younger residents are under-represented in this study. It is unclear if non-contacted residents may have been more or less likely to enroll in HIV care. Finally, although sexual risk behavior data including consistent condom use, number of sex partners in the past 3 months, and knowledge of partner’s HIV status were collected at the time of HBTC, prior to participant’s learning their HIV status, they were not collected afterwards so we are unable to examine how these behaviors may have changed after residents learned their HIV status.

Despite these limitations, this study showed the population acceptability of a large scale HBTC program at diagnosing new HIV infections and promoting family and couple testing with facilitated disclosure. This study also identified factors associated with early enrollment into HIV care following HBTC. Future programmatic efforts should focus on other complementary HIV testing strategies (i.e., routine facility-based provider-initiated HTC services, offering evening and weekend HTC services, male circumcision programs, mobile outreach programs, and workplace programs) to capture men and younger residents who may be missed during HBTC initiatives.

As earlier ART initiation becomes increasingly emphasized for both its HIV care and prevention effects, identifying effective strategies to increase the number of HIV-positive individuals who are enrolled and retained in HIV clinical care will be critical to achieve optimal program impact [31]. Ensuring that all HIV-positive individuals identified through HBTC and other HIV testing services are linked to HIV clinical care will require coordination between testing and HIV care and treatment program staff and systems. For HBTC programs, potential strategies include counselors initiating the linkage process by providing a list of nearby HIV care facilities to all individuals testing HIV-positive and instituting follow-up services through peer educators, community health workers, or other staff to ensure that all residents enroll in HIV clinical care. Health facilities should evaluate the effectiveness of promising strategies such as patient escorts, patient navigation systems, intensive case management, home-based outreach, and text messaging to ensure HIV-positive individuals enroll and are retained in care [32]. Finally, developing appropriate and sustainable databases and systems to track patients from diagnosis through enrollment and retention in care should be prioritized to enable better patient care and monitoring [33].

References

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), ICF Macro: Kenya demographic and health survey 2008–09. Available at http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/fr229/fr229.pdf (2010). Accessed 2 Feb 2012.

Crum NF, Riffenburgh RH, Wegner S, Agan B, Tasker S, Spooner K, et al. Comparisons of causes of death and mortality rates among HIV-infected persons: analysis of the pre-, early, and late HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) eras. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:194–200.

Lima V, Harrigan R, Bangsberg D, Hogg R, Gross R, Yip B, et al. The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:529–36.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, HPTN 052 Study Team, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505.

Attia S, Egger M, Muller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:1397–404.

Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiaire J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–8.

Kenya National AIDS Control Council. Kenya National AIDS Strategic Plan, 2009/2010–2012/13: delivering on universal access to services. Nairobi: National AIDS Control Council; 2009.

Adazu K, Lindblade KA, Rosen DH, Odhiambo F, Ofware P, Kwach J, et al. Health and demographic surveillance in rural western Kenya: a platform for evaluating interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality from infectious diseases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:1151–8.

Ombok M, Adazu K, Odihambo F, Bayoh N, Kiriinya R, Slutsker L, et al. Geospatial distribution and determinants of child mortality in rural western Kenya 2002–2005. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:423–33.

Zeger S, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30.

Hatcher A, Turan J, Leslie H, Kanya L, Kwena Z, Johnson M, et al. Predictors of linkage to care following community-based HIV counseling and testing in rural Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1295–307.

Assefa Y, Van D, Mariam DH, Kloos H. Toward universal access to HIV counseling and testing and antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: looking beyond HIV testing and ART initiation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:521–5.

Govindasamy D, van Schaik N, Kranzer K, Wood R, Matthews C, Bekker LG. Linkage to HIV care from a mobile testing unit in South Africa by different CD4 count strata. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(3):344–52.

Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers, and facilitators for linkage to ART care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS. 2012; (epub).

Posse M, Baltussen R. Barriers to access to antiretroviral treatment in Mozambique, as perceived by patients and health workers in urban and rural settings. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:867–75.

Zachariah R, Harries AD, Manzi M, Gomanj P, Teck R, Philips M, et al. Acceptance of anti-retroviral therapy among patients infected with HIV and tuberculosis in rural Malawi is low and associated with cost of transport. PLoS One. 2006;1:e121.

Hardon AP, Akurut D, Comoro C, Ekezie C, Irunde HF, Gerrits T, et al. Hunger, waiting time and transport costs: time to confront challenges to ART adherence in Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19:658–65.

Miller CM, Kelthapile M, Rybasack-Smith H, Rosen S. Why are antiretroviral treatment patients lost to follow-up? A qualitative study from South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(suppl 1):48–54.

Harries AD, Zachariah R, Lawn SD, Rosen S. Strategies to improve patient retention on antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(suppl 1):70–5.

Geng EH, Nash D, Kambugu A, Zhang Y, Braitstein P, Christopoulos KA, et al. Retention in care among HIV-infected patients in resource-limited settings: emerging insights and new directions. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:234–44.

Abaynew Y, Deribew A, Deribe K. Factors associated with late presentation to HIV/AIDS care in South Wollo Zone Ethiopia: a case–control study. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:8.

Lawn S, Harries A, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–908.

Kigozi IM, Dobkin LM, Martin JN, Geng EH, Muyindike W, Emenyonu NI, et al. Late-disease stage at presentation to an HIV clinic in the era of free antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:280–9.

Battegay M, Fluckiger U, Hirschel B, Furrer H. Late presentation of HIV-infected individuals. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:841–51.

Lawn SD, Harries AD, Wood R. Strategies to reduce early morbidity and mortality in adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Curr Opin HIV/AIDS. 2010;5:18–26.

Lahuerta M, Lima J, Elul B, Okamura M, Alvim MF, Nuwagaba-Birbonwoha H, et al. Patients enrolled in HIV care in Mozambique: baseline characteristics and follow-up outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:e75–86.

Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, Biraro IA, Wyatt MA, Agabji O, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e11.

Medley A, Garcia-Moreno C, McGill S, Maman S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:299–307.

Rosen S, Fox M. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001056.

Wachira J, Kimaiyo S, Ndege S, Mamlin J, Braitstein P. What is the impact of home-based HIV counseling and testing on the clinical status of newly enrolled adults in a large HIV care program in Western Kenya? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(2):275–81.

Nakanjako D, Colebunders R, Coutinho AG, Kamya MR. Strategies to optimize HIV treatment outcomes in resource-limited settings. AIDS Rev. 2009;11:179–89.

Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800.

World Health Organization: Patient monitoring guidelines for HIV care and antiretroviral therapy. Available at http://www.who.int/3by5/capacity/ptmonguidelinesfinalv1.PDF (2012). Accessed 10 Mar 2012.

Acknowledgments

This work received funding support through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement 5U19CI000323-05). The authors would like to express their gratitude to Maurice Ombok and Alan Rubin for their assistance with the GIS mapping data and to Jan Moore for her insightful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. The authors are also grateful for the extraordinary efforts of the HBTC counselors, the field and data management staff of the HDSS, and the facility-based peer educators without whom this study could not have taken place. The authors would also like to thank KEMRI and CDC/KEMRI administrative staff for the support they provided and continue to provide to the project. Finally, the authors would like to thank the HDSS residents for their continued participation. This paper was published with the approval of the director of the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Conflict of interest

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Medley, A., Ackers, M., Amolloh, M. et al. Early Uptake of HIV Clinical Care After Testing HIV-Positive During Home-Based Testing and Counseling in Western Kenya. AIDS Behav 17, 224–234 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0344-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0344-5