Abstract

Linkage, engagement, retention and adherence to care are necessary steps along the HIV care continuum. Progression through these steps is essential for control of the disease and interruption of transmission. Identifying and re-engaging previously diagnosed but out-of-care patients is a priority to achieve the goals of the National HIV/AIDS strategy. Participants in the EnhanceLink cohort who were previously diagnosed HIV+ (n = 1,203) were classified as not-linked to of care and non-adherent to medication prior to incarceration by self report. Results based on multivariate models indicate that recent homelessness as well as high degrees of substance abuse correlated with those classified as not-linked to care and non-adherent to medications while having insurance was associated with being linked to care and adherent to care. The majority of detainees reported being linked to care but not currently adherent to care confirming that jails are an important site for re-engaging HIV+ individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While overall morbidity and mortality for HIV infected individuals in the United States have markedly improved since the introduction of potent antiretroviral therapy, these successes are limited to those who remain in regular medical care. Recent analyses show only 50 % of individuals previously diagnosed with HIV in the United States are fully engaged in care and only 19–28 % of all people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHA) are adherent to HAART with undetectable viral loads [1, 2]. The public health ramifications of these data are clear as engagement and retention in care are a crucial component of the National Institutes of Health “seek, test, and treat” strategy in order to impact the stagnant annual incidence of over 56,000 new HIV infections in the United States [3]. Given the dual benefits of treatment improving one’s individual health [4] as well as decreasing the risk of transmission to others in the community [5], there is an urgent need to identify interventions to re-engage out-of-care PLWHA [2, 6]. Strategies to improve retention in care rely on the individual being locatable and willing to engage. For many patients who are out of care, substance use, untreated mental illness or unmet basic needs prevent them from being reached by traditional outreach efforts.

Venue based outreach, including in jails, has been used for HIV prevention activities including education and testing. With 17 % of PLWHA spending time in a correctional facility [7] and the frequency that jail detainees experience conditions that generally affect engagement in medical care, such as lack of resources, competing basic needs, and mental health and/or substance abuse co-morbidities [6–8], jails may offer unique opportunities to link or re-engage those who are not actively in care. Many prisons (which house sentenced criminals) provide discharge planning services which may include a medication supply and appointments post release for HIV+ inmates. In contrast, 75 % of jail detainees return directly to the community upon release rather than being sent to prison. Discharge planning is rare among jails due to their chaotic and unpredictable nature. For persons who remain in jail more than a day or two, maintaining or resuming their HIV care is essential to their health and provision of medical services is required by law. Time and personnel restrictions as well as legal barriers such as HIPAA frequently limit or delay external confirmation for jail medical staff and as such, most personal health information is gathered by self report, including current medications, recent lab results and engagement in care. Despite the limitations in verified data or resources, correctional facilities should offer opportunities for improving one’s health, well being and behavior including identification and re-engagement of those who are out of care and strengthen ties to those who are marginally engaged or at high risk of falling out of care.

Jails also offer the opportunity to address risk behaviors for HIV and treat co-morbid diseases associated with HIV and criminal activities, including addiction and untreated mental illness [9]. Providing consistent treatment for addiction and mental illness is the desired standard of care, although data that providing medication for mental illness reduces recidivism are lacking [10, 11]. When common structural barriers that reduce access to medical care are alleviated, individuals that are usually not interested or willing to address their health issues theoretically may be more receptive to services such as disease education, medication evaluation and adherence counseling. Ignoring HIV issues in jail does not lower the cost to society, but rather transfers it from one public entity to another [12], as most jail detainees will return to the community from which they are arrested.

As part of a multi-site project evaluating unique interventions designed to improve linkage and engagement to care for HIV-positive jail detainees upon release from incarceration, we sought to quantify the medical and social needs of PLWHA who enter jail focusing on those who report not being linked to care or not being adherent to antiretroviral medication (ART).

Methods

EnhanceLink is a federally funded, 10-site demonstration project that is implementing and evaluating diverse models of HIV testing and linkage in jail settings. Demonstration sites are located in Atlanta, GA; Chester, PA; Chicago, IL; Cleveland, OH; Columbia, SC; New Haven, CT; New York, NY; Philadelphia, PA; Providence, RI; and Springfield, MA and details of interventions have been previously described [8]. The multisite study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Emory University and Abt Associates, and individual site programs were reviewed by the responsible IRBs (including special review criteria for prisoners). A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained for the study.

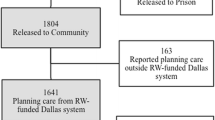

HIV-positive clients were recruited to participate in a voluntary evaluation of their experience in the linkage programs. Other than a mandate that participants be at least 18 years of age, sites varied in criteria for enrollment in the client-level evaluation. This analysis focuses on previously diagnosed HIV-positive clients to assess their engagement in care prior to incarceration (Fig. 1).

Data Collection

From January 2008 through March 2011, project staff administered a baseline assessment to enrolled detainees. For the present analysis, clients diagnosed with HIV during this jail stay were excluded (n = 53), as were clients missing the baseline interview (n = 15); one person was both newly diagnosed and missing the baseline form. Of note, 22 clients reported being newly diagnosed on the baseline interview were later noted by jail chart review to have been diagnosed prior to the index incarceration and thus were included. Twelve hundred and three previously diagnosed participants had completed baseline interviews and are described below. Baseline surveys included questions on demographic characteristics, substance use and mental and physical health and were most often completed within the first few days of incarceration. Medication adherence and engagement with an HIV care physician were obtained via self report. Laboratory values were collected from review of the jail chart and included results from prior to incarceration, if available.

Newly incarcerated individuals were asked “During the 30 days before your most recent incarceration, did you have a usual health care provider or place where you get HIV care?” Those who answered “yes” were classified as “linked”; those not answering “yes” were deemed to be “not-linked”. “Adherent to ART” was defined by self report of more than 90 % adherence to HIV treatment in the 7 days prior to incarceration and was limited to those who reported ever taking HIV medications. Severity of drug and alcohol use was assessed using the addiction severity index (ASI) [13, 14]. A psychiatric composite index and an employment composite index were also compiled for each participant based on their answers to questions previously described in the ASI Composite Score Manual [13, 15]. The 12-item short form (SF12) scores were calculated to assess subjective sense of mental and physical well being [9].

Statistical Analysis

For both measures of engagement, we assessed potential associations with demographic, social, mental health, drug and alcohol characteristics. Variables considered for analysis included gender, race, homelessness, food availability, relationship status, sexual orientation, ASI composite scores in the domains of alcohol use, substance use, psychiatric problems and employment, and SF12 scores. For categorical risk factors, the Chi-square was used to test for significance of the bivariate associations between each outcome and each risk factor. For continuous factors, we used logistic regression to quantify and test the individual associations. Variables with p values less than 0.1 in the bivariate analyses were included in a multivariate model for each outcome. Only variables with significant associations were retained in the model. Tables 1 and 2 show variables included in each multivariate model and the adjusted odds ratios for those with significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (Foundation for Statistical Computing; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) version 11.0.

Results

Demographic data on the 1,203 clients included in the analysis is shown in Table 1. For the 1,099 enrollees with a known release date, the mean duration of incarceration was 107 days, with a median of 63 days and a mode of 5 days. Mental health concerns were very common during the 30 days prior to incarceration, with 66 % of enrollees reporting significant mental health issues in the 30 days prior. Depression and anxiety were the most commonly reported mental health concerns, and both were reported by nearly half the population (Table 1). By self report, the population was very experienced in the criminal justice system, with a mean of 26.6 arrests and median of 15.0 per detainee ever.

When asked at the time of incarceration if they had a provider in the 30 days prior to incarceration, 75.1 % of detainees reported having a community HIV provider. Of the 79.3 % of detainees who had ever been on HIV medications, 58.6 % reported taking them in last 7 days; 40.4 % reported taking greater than 90 % of medications (Table 2).

Sixty-two percent (n = 764) of the population who reported ever taking medication had a viral load result available that occurred in the “pre-incarceration timeframe”. Of these, 40 % who had ever taken medications were suppressed at the time of incarceration and 54 % of participants reporting >90 % adherence to medications had suppressed viral loads at the time of incarceration. Because of the frequency of missing data, further analysis was not pursued.

Detainees classified as “not-linked” (n = 287 reporting no current medical provider) were more likely to be female (AOR 1.67; CI 1.17–2.38), self report as black (AOR 1.81; CI 1.18–2.78), have experienced recent homelessness (AOR 2.06; CI 1.46–2.90) and be much less likely to have any type of health insurance (AOR 0.16; CI 0.11–0.23) than those who were classified as “linked”. The “not-linked” group also had a significantly higher mean drug use composite score (AOR 5.62; CI 1.39–22.76), reflecting a greater degree of substance abuse. Both groups, however, had mean composite scores greater than the national average of those entering drug treatment programs (mean scores of 0.15 for those “in care” and 0.17 for those “out of care”) [13] and above or near the 0.16 cutoff recommended for diagnosing substance abuse (Table 2) [10].

Those classified as non-adherent to ART (n = 564 reporting <90 % adherent to HIV medication) were also more likely to be female (AOR 1.73; CI 1.18–2.54), experience recent homelessness (AOR 1.86; CI 1.29–2.70), have more severe substance abuse concerns (AOR 8.41; CI 2.11–33.55) and report food instability (AOR 1.75; CI 1.20–2.57). Similar to the out of care group, those not adherent to ART were also less likely to have health insurance (AOR 0.33; CI 0.20–0.54) and less likely to report having a trade, skill or profession (AOR 0.56; CI 0.41–0.78). Unexpectedly, those non-adherent to ART were less likely to have severe psychiatric symptoms (AOR 0.48; CI 0.23–0.96), though mean scores for both the adherent and non-adherent groups (means of 0.28 and 0.30, respectively) were well above the threshold for classification of serious mental illness (Table 3).

Among patients not currently taking HIV medication, 23 % reported drug and alcohol use as a reason for not taking medications while structural reasons (“couldn’t get”, “lost insurance”, “away from meds”) were cited among 22 % of patients. Other less frequent reasons included side effects (6 %), social emotional issues (including being depressed, in denial and wanting to give up 5 %) and not yet prescribed medications by the doctor (5 %).

Discussion

This analysis supports the clear benefit of seizing the opportunity for re-engaging individuals living with HIV and providing services during their stay in jail; this setting provides a window of opportunity to intervene, educate and engage those with great need. Despite limitations on what data were accessible, it reflects the frequent reality for provision of jail based medical care and services. Many individuals that are currently out of care may know where they could get care but fail to connect due to social and medical barriers in the community.

Having some type of health coverage was the only factor associated with both having a provider and adhering to ART. In the recent “Medicaid experiment in Oregon”, recipients reported better overall health, less depression and improved sense of well being [11]. The potential of health care reform and the implications of greater access to Medicaid for the population described in the paper is exciting indeed. With health care reform on the horizon, jails offer an opportunity to enroll clients prior to release.

Not surprisingly, individuals who by self report were not-linked to care or non-adherent to ART also reported factors previously associated with poor retention in care including high rates of substance abuse, housing instability and unemployment. Our findings are consistent with existing literature that shows basic needs for housing stability and food security must first be met before the individual can focus on health care services [12, 16]; these needs also affect survival [17]. While there were many needs noted by those out of care, it is important to note the high frequency with which similar social issues were reported by detainees who were reportedly linked to care. This analysis illustrates jails as an opportune location to provide linkage to care and treatment in jail and to forge relationships to medical and supportive services in the community.

The unexpected finding of less severe mental health symptoms correlating with worse reported adherence to care merits further consideration and study. Most studies of mental illness and adherence to ART, have found mental illness associated with poorer adherence to and persistence on ART, and most utilized a specific diagnostic tool such as the Structured Clinical Interview (SCID) or the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), or those targeting symptoms of a specific mental illness such as those validated for identifying major depressive disorder symptomatology (e.g. CES-D, BDI, BSI) [18]. Therefore the use of ASI psychiatric composite index, reflecting general psychiatric severity, limits direct comparison with those more diagnosis-specific studies. A different possibility to consider is whether persons with a greater degree of psychiatric illness seek out health care and take medication more for the psychiatric reasons, and this facilitates the linkage to HIV care and adherence to ART. Himelhoch et al. [19] observed a lower probability for ART discontinuation in the first and second years in participants with a severe mental disorder compared to participants with no mental disorders; additionally, among participants with a mental disorder, those with over five mental health visits per year were less likely to discontinue ART than those with no visits. On the other hand, it could be that those reporting less psychiatric severity are describing a period of less concern for HIV, and whether due to denial, drug use, or other priorities, they could potentially be self-treating psychiatric symptoms with illicit drugs.

The unpredictability of jail makes it a challenging environment for provision of healthcare services. Detainees may be in court, disciplinary segregation, or otherwise unavailable. Correctional staff may be reluctant to allow community staff easy access to detainees, especially when it leads to more work or more cost to the system. Rapid turnover in jails is a commonly cited barrier to providing services and may be valid concern for many types of services. Despite this concern, most EnhanceLink sites were able to meet with clients enrolled in the individual level evaluation multiple times before release as only 10 % of enrollees were released in 10 days or less. The longer jail stay seen in this cohort is not typical of all jail detainees and may reflect enrollment bias. Length of stay for all HIV+ detainees was collected routinely at one site as part of this study and they note 67 % of HIV+ detainees were detained for greater than 1 week during the enrollment period, a reasonable length of time to initiate discharge planning, even for small community-based organizations. Reasons that eligible inmates did not participate in EnhanceLink were not routinely collected, though anecdotally they ranged from not interested because of a “perceived lack of needs” to “not interested in engaging in care.” Some were likely to be sentenced to prison for more than a year. Only two sites specifically excluded severely mentally ill inmates; though these inmates were often not included at other sites for reasons including lack of access to them by staff members and inability to consent to participation.

Adherence to medication is crucial for virologic suppression. With less than half of participants reporting 90 % or greater adherence, but nearly 80 % on medications at some point, jail offers an opportunity to provide medication in a supervised environment, as well as provide education and strategies to patients who struggle with taking their medications “on the outside”. By self report, a mere 40.4 % of participants were sufficiently adherent to medical care (medication) at a level to improve one’s health, affect disease progression or prevent transmission to their partner(s).

By self report, 56 % of detainees would not be classified as in care either by not having a provider or not consistently taking prescribed medications. Ideally, the most recent office visit would be checked to determine the degree to which clients were linked to care prior to incarceration, though this is often not available to jail staff in a timely fashion. Only three sites had access to outside prior laboratory findings for the purpose of this study, a commonly used proxy measure of engagement in care. When we applied the more rigorous definition of engaged in care as “having had HIV labs during the 6 months prior to incarceration” among those sites with available data, a mere 20 % met the definition of “engaged in care,” yet 86 % of this subset reported having an HIV provider. Self reported adherence to medication may serve as a better marker for being in care among this population; however, only half of those reporting excellent adherence to medication and a documented viral load near the time of admission were virologically suppressed.

Conclusion

Regardless of linkage or adherence to HIV care prior to incarceration, most enrollees had significant medical or social needs. Engaging HIV+ jail detainees in treatment prior to community release should improve the likelihood of accessing needed community resources to address the structural barriers to care; treating co-morbid illnesses has also been shown to improve retention in care [20]. Some models suggest that co-located (jail and community) services may increase successful linkages by providing a common link during the fragile transition period immediately following release from jail [21, 22].

While many participants reported having a provider, the lack of adherence to HIV care suggests most people were out of care or not fully engaged in care at the time of jail admission; further work in this cohort will look to programs to remedy this. Having some form of health insurance was the strongest correlate for being linked and adherent to care in this study; this highlights the importance of maintaining or reestablishing health insurance while in jail and the need to implement transitional programs for those entering jails from and returning to Health Homes. With the increasing financial burden of health care services on local jails, transitional care coordination services that provide linkages to care for people leaving jails will be essential to achieving health care reform objectives for more accountable care. There are a number of successful models with academic or community-based providers delivering HIV care within correctional settings; in others, the local health department partners with community-based providers [23]. These partnerships may provide a cost savings to the jail, especially for medications [24]. With an increasing focus on engagement and retention in care, jail and community-based providers need to establish partnerships that enhance HIV care and services for patients in correctional settings.

References

Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800.

Signs Vital. HIV prevention through care and treatment—United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;2(60):1618–23.

Montaner JS, Hogg R, Wood E, Kerr T, Tyndall M, Levy AR, et al. The case for expanding access to highly active antiretroviral therapy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. Lancet. 2006;368(9534):531–6.

Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(11):1493–9.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States.

Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(11):e7558.

Draine J, Ahuja D, Altice FL, Arriola KJ, Avery AK, Beckwith CG, et al. Strategies to enhance linkages between care for HIV/AIDS in jail and community settings. AIDS Care. 2011;23(3):366–77.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Rikoon SH, Cacciola JS, Carise D, Alterman AI, McLellan AT. Predicting DSM-IV dependence diagnoses from Addiction Severity Index composite scores. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31(1):17–24.

Baicker K, Finkelstein A. The effects of Medicaid coverage–learning from the Oregon experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):683–5.

Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, Royal S, Aidala A, Stall R, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):493–503.

McLellan AT, Cacciola JC, Alterman AI, Rikoon SH, Carise D. The Addiction Severity Index at 25: origins, contributions and transitions. Am J Addict. 2006;15(2):113–24.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168(1):26–33.

McLellan P, Griffith J, Parente R, McLellan T. Addiction severity index composite score manual. Pennsylvania: The University of Pennsylvania/Veterans Administration Center for Studies of Addiction.

Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):217–20.

Schwarcz SK, Hsu LC, Vittinghoff E, Vu A, Bamberger JD, Katz MH. Impact of housing on the survival of persons with AIDS. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:220.

Springer SA, Dushaj A, Azar MM. The Impact of DSM-IV Mental disorders on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among adult persons living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2012 May 30 [Epub ahead of print].

Himelhoch S, Brown CH, Walkup J, Chander G, Korthius PT, Afful J, et al. HIV patients with psychiatric disorders are less likely to discontinue HAART. AIDS. 2009;23(13):1735–42.

Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Flanigan TP. A public health model to connect correctional health care with communities. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(8):1249–50.

Lincoln T, Kennedy S, Tuthill R, Roberts C, Conklin TJ, Hammett TM. Facilitators and barriers to continuing healthcare after jail: a community-integrated program. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29(1):2–16.

Hampden county: a model for seamless care. AIDS Policy Law. 1999;14(22):9.

Rich JD, Wohl DA, Beckwith CG, Spaulding AC, Lepp NE, Baillargeon J, et al. HIV-related research in correctional populations: now is the time. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):288–96.

Werling K, Abraham S, Strelec J. The 340B Drug Pricing Program: an opportunity for savings, if covered entities such as disproportionate share hospitals and federally qualified health centers know how to interpret the regulations. J Health Care Finance. 2007;34(2):57–70.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by a grant through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV Bureau (H97HA08543). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of DHHS. Responsibility for the content of this report rests solely with the named authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avery, A.K., Ciomcia, R.W., Lincoln, T. et al. Jails as an Opportunity to Increase Engagement in HIV Care: Findings from an Observational Cross-Sectional Study. AIDS Behav 17 (Suppl 2), 137–144 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0320-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0320-0