Abstract

We used the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (N = 14,322) to measure associations between non-injection crack-cocaine and injection drug use and sexually transmitted infection including HIV (STI/HIV) risk among young adults in the United States and to identify factors that mediate the relationship between drug use and infection. Respondents were categorized as injection drug users, non-injection crack-cocaine users, or non-users of crack-cocaine or injection drugs. Non-injection crack-cocaine use remained an independent correlate of STI when adjusting for age at first sex and socio-demographic characteristics (adjusted prevalence ratio (APR): 1.64, 95 % confidence interval (CI): 1.16–2.31) and sexual risk behaviors including multiple partnerships and inconsistent condom use. Injection drug use was strongly associated with STI (APR: 2.62, 95 % CI: 1.29–5.33); this association appeared to be mediated by sex with STI-infected partners rather than by sexual risk behaviors. The results underscore the importance of sexual risk reduction among all drug users including IDUs, who face high sexual as well as parenteral transmission risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Given the persistence of the sexually transmitted infection including HIV (STI/HIV) epidemics in the United States (US) [1, 2], identification of the populations at greatest infection risk remains a public health priority so that STI/HIV testing, treatment, and prevention interventions reach those in greatest need.

Drug users have long been recognized as priority populations for prevention of STIs including sexually transmitted HIV [3]. Elevated infection rates among drug users result due to a multitude of STI determinants including elevations in numbers of sex partnerships and sex trade, decreases in condom use, and engagement in high-risk sexual networks in which there is elevated risk of links to STI-infected sexual partners. While use of drugs is thought to increase levels of risk-taking, in addition, social and economic factors such as the need to trade sex for drugs also drive sex risk.

There exists great heterogeneity within drug using populations, and differential sexual risk within drug-using groups has been documented [3]. The relationship between crack-cocaine use and sexual transmission risk is well established [3, 4], and studies suggest that crack-cocaine users may experience elevated risk of STI compared with other drug-using groups. Specifically, crack-cocaine users consistently report higher levels of sexual risk behaviors including multiple and concurrent partnerships and sex trade compared with non-users of drugs and with other drug-using populations who do not use crack-cocaine, including injection drug users (IDUs) whose primary drug is heroin [3–8]. Crack-cocaine use also is strongly associated with having an STI-infected sex partner [9], with biologically-confirmed STI [5, 10–12], and with sexually-transmitted HIV infection [13, 14]. Extant literature has suggested that cocaine-related increases in impulsivity drive the elevated levels of STI risk observed in cocaine users [8], while elevations in partnership levels due to sex trade for crack/cocaine also is well documented [3].

When assessing infectious disease risk among IDUs, researchers and program planners have focused on the drug-related HIV transmission risk in this group given the high transmission efficiency of parenteral versus sexual HIV transmission [3]. However, IDUs exhibit elevated levels of sexual risk-taking [6, 7, 15], have links to high risk networks and hence face elevated risk of sex with infected partners [6, 15], and have high risk of STI [5, 10, 15, 16] and HIV infection due to sexual transmission [17–19]. In fact, sexual HIV transmission among IDUs may be underestimated; currently, an HIV infection detected in an individual who reports both IDU and high-risk heterosexual activity is classified as a case attributable to IDU alone, while the potential role of heterosexual transmission is not documented [2]. The importance of sexual risk among IDUs likely has been underestimated [16].

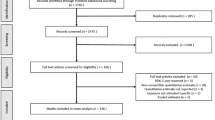

Though extant research in geographically distinct samples has documented high STI/HIV risk among both non-injection and injection drug users, no prior study, to our knowledge, has compared biologically-confirmed sexually transmissible infection among non-injection drug users and IDUs versus non-users of these drugs in a large nationally-representative sample. The strong link between drug use and STI/HIV risk points to the need for such a study at the national level. Given both drug use and STI risk peak in late adolescence and early adulthood [20–23], measurement of the association in a population of young adults is warranted. In addition, though numerous studies have documented the link between non-injection and injection drug use and sexual risk indicators including multiple partnerships, inconsistent condom use, and links to high-risk networks, research that identifies the most important determinants of infection transmission in drug-using populations is limited. Specifically, there is a need to evaluate the degree to which elevations in behavioral STI/HIV determinants including multiple partnerships or unprotected sex versus network factors such as elevated risk of sex with infected partners may drive sexually transmissible infection risk among drug users.

To expand existing research on non-injection and injection drug use and STI/HIV risk among young adults in the US, we used Wave III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) (N = 14,322) to assess non-injection crack-cocaine and injection drug use, sexual risk indicators, and biologically-confirmed infection with Chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomoniasis among young adults in the US. These STIs constitute a clear public health concern. They are highly prevalent and underdiagnosed [23–25], result in considerable morbidity [26–29], increase HIV transmission [30–34], and can serve as biomarkers of unprotected sex and potential exposure to HIV. One objective of this study was to compare sexual risk behaviors, links to infected partners, and biologically-confirmed STI among IDUs, crack-cocaine users who did not inject, and those who neither used crack-cocaine nor injection drugs in order to evaluate which group was at elevated risk of infection. We hypothesized that sexual risk behaviors and STI would be elevated among both drug-using groups, but that levels of STI risk would be higher among non-injection crack-cocaine users than among IDUs or non-users of drugs, given the elevations in impulsivity and related sexual risk-taking associated with crack-cocaine use [8]. The second study objective was to evaluate the degree to which sexual risk behaviors versus sex with an STI-infected partner may explain elevated STI levels among the different drug-using populations in order to better understand which factors should be targeted in interventions designed for drug-using populations. We hypothesized that among both non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs, elevations in STI would be attributed to increased levels of both sexual risk behaviors and sex with STI-infected partners.

Methods

Add Health is a longitudinal cohort study designed to investigate health from adolescence into adulthood in a nationally-representative sample of US youth. The study design has been described in detail elsewhere [35–40]. Wave I (1994–1995) data collected from adolescents and parents were used to provide socio-demographic background characteristics on respondents. During Wave III (2001–2002; range: 18–28 years), respondents were re-interviewed about drug use and sexual risk. Additionally, urine specimens were collected for determination of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea by ligase chain reaction (LCR; Abbott LCx® Probe System, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) and Trichomonas vaginalis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Amplicor CT/NG Urine Specimen Prep Kit, Roche Diagnostic Systems, Indianapolis, IN). Evaluation studies suggest that urine-based LCR detects chlamydia with a sensitivity ranging from 80 to 96 % and a specificity ranging from 96 to 100 % in asymptomatic men and women [41, 42]. A systematic review of evaluations of LCR for gonorrhea detection indicated that the sensitivity ranged from 94 to 100 % in women and from 98 to 100 % in men, and that the specificity ranged from 99 to 100 % in women and men [43]. The PCR assay is estimated to detect trichomoniasis in asymptomatic men and women with a sensitivity of 91 to 92 % and a specificity of 93 to 95 % [40].

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Exposure: Non-injection Crack-cocaine and Injection Drug Use

Respondents were asked, “Since June 1995, have you injected (shot up with a needle) any illegal drug, such as heroin or cocaine?” and “Since June 1995, have you used any kind of cocaine—including crack, freebase, or powder?” Based on these survey items, we coded a three-level nominal categorical drug use variable indicating whether respondents were non-injecting crack-cocaine users, IDU (who also may have had a history of crack-cocaine use), or non-users of crack-cocaine or injection drugs.

Outcomes: Sexual Risk Indicators and STI

We assessed three dichotomous indicators of sexual risk based on Wave III data: two or more partners in the past year; four or more partners in the past year; and inconsistent condom use in the past year defined by report of failure to use condoms all of the time during vaginal sex in the past year. We also examined an indicator of sex with an STI-infected partner, defined by report of sex in the past year with at least one partner who the respondent reported to have ever had an STI. Since this variable is based on the respondent’s report of his or her partner’s infection status rather than obtained through network tracing and interviews with and STI testing among sex partners, we consider this a proxy indicator of involvement in a high-risk sexual network. We also assessed biologically-confirmed curable STI, defined by a positive test result for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, or Trichomonas vaginalis on the Wave III urine specimen versus a negative result for all three tests.

Data Analysis

For all analyses, we used survey commands in Stata Version 10.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX) to account for stratification, clustering, and unequal selection probabilities, yielding nationally representative estimates. We used bivariable analyses to calculate weighted prevalences of non-injecting crack-cocaine use, injection drug use, and non-use of crack-cocaine or injection drugs by participant socio-demographic characteristics. We also calculated the prevalence of alcohol use, marijuana, crack-cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, and other drug use among non-injecting crack-cocaine users, IDUs, and non-users of these drugs, respectively. We estimated unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between being an IDU or a non-injecting crack-cocaine user versus being a non-user of these drugs (the referent) and adulthood sexual risk indicators and STI using a Poisson model without an offset, specifying a log link and probability weights [44, 45]. In the first set of multivariable models, we adjusted for age at first vaginal intercourse (referred to from this point forward as age at first sex) and socio-demographic characteristics including race/ethnicity; gender; age; mother/primary female caretaker’s education measured by Wave I self-report if the mother/primary female caretaker was interviewed, otherwise by adolescent’s report; and Wave III low functional income status in the past year, defined by the inability of the respondent or his/her household to pay rent/mortgage or utilities in the past year. To assess the degree to which use of alcohol and other drugs may influence associations between non-injection crack-cocaine and injection drug use and STI/HIV risk, in a second set of models, we adjusted for age at first sex and socio-demographic characteristics plus indicators of alcohol and other drug use in the year prior to Wave III, including marijuana use; frequency of getting drunk, defined as getting drunk at least once per week, less than once per week but more than one to two days in the past year and one to two days in the past year versus never in the past year; and crystal methamphetamine use.

When disproportionate STI levels were observed among non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs, we explored whether the sexual risk indicators–multiple partnerships, inconsistent condom use, or sex with an infected partner–may have accounted for the elevated infection levels in these populations. Specifically, we compared associations between drug use indicators and STI adjusted for age at first sex and socio-demographic characteristics with associations further adjusted for hypothesized sexual risk behavior mediators: multiple partnerships, consistent condom use, and sex with an infected partner. If the associations between drug use and STI were attenuated on further adjustment for the sexual risk intermediates, we assumed these variables mediated the association between drug use and STI.

All models used complete case analysis. Approximately 4 % of respondents or less were missing on all exposures, outcomes, and covariates, with the exception of two variables. Eighteen percent of respondents had missing data for the indicator for biologically-confirmed STI; of the Wave III participants, 7.9 % refused to provide a urine specimen, 1.6 % were unable to provide a urine specimen, 2.9 % provided urine specimens that could not be processed due to shipping or laboratory problems, and 6.6 % did not have results for all 3 STI tests. In addition, 10 % were missing data on mother/primary female caretaker’s education. While the prevalence of missing or incomplete STI and mother/primary female caretaker’s education data was not associated with race/ethnicity, missing data on these variables was more common among males than females and was associated with increasing age.

Results

Young Adult Sociodemographic Characteristics

The analytic sample was approximately equal in gender (49 % female, 51 % male) (Table 1). Approximately 68 % were White, 16 % were African American, 12 % were Latino, 1 % was Native American, and 4 % were Asian American. Among respondents, half of their mothers/primary female caretakers attained a college education or greater (50 %), one-third attained only a high school education (34 %), and 16 % attained less than a high school education. Fourteen percent of respondents reported difficulty paying for housing or utilities in the past year.

Among young adults, 10 % reported non-injection crack-cocaine use and 1 % reported injection drug use since 1995, when the Wave I interview occurred. Though no significant age differences were observed between non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs, women were less likely than men to be drug users (Table 1). Native Americans were much more likely to report non-injection crack-cocaine and injection drug use (15 % and 4 %, respectively) than Whites (12 % and 1 %, respectively), Latinos (10 % and 1 %, respectively), and Asian Americans (6 % and 0.5 %, respectively), while African Americans were much less likely than other groups to report non-injection crack-cocaine and injection drug use (3 % and 0.4 %, respectively). High maternal education was associated with higher levels of drug use, while low functional income status was associated with higher levels of use.

Use of Alcohol and Other Drugs among Non-injection Crack-cocaine Users and IDUs

Non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs reported disproportionate use of alcohol, marijuana, crack-cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, and/or other illicit drugs compared with non-users of these drugs (Table 2). One-third of non-injection crack-cocaine users (32 %) and one-fifth of IDUs (20 %) reported getting drunk at least once per week in the year prior to Wave III versus less than one-tenth of non-users (8 %). Nearly 80 % of non-injection crack-cocaine users and 73 % of IDUs versus 27 % of non-users used marijuana in the past year. While 100 % of non-injection crack-cocaine users had, by definition, used crack-cocaine since Wave I and 63 % had used crack-cocaine in the past year, injection drug users also reported high levels of crack-cocaine use since Wave I (71 %) and in the past year (45 %). IDUs also were more likely than non-injection crack-cocaine users to report crystal methamphetamine use since Wave I (63 % versus 36 %, respectively) and in the past year (42 % versus 17 %, respectively).

Sexual Risk Indicators and STI

In the year prior to Wave III, the weighted prevalence of two or more sex partnerships was 28 %, four or more sex partnerships was 8 %, inconsistent condom use was 78 %, and sex with an STI-infected partner was 8 %. The weighted prevalence of STI was 6 %; 4 % were infected with Chlamydia, 0.4 % were infected with gonorrhea, and 2 % were infected with trichomoniasis.

Associations: Drug Use Category and Sexual Risk Indicators

Compared to those who had not used crack-cocaine or injection drugs, non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs were more likely to report having two or more sex partnerships in the past year (crack-cocaine PR: 1.81, 95 % CI: 1.65-1.98; IDU PR: 1.45, 95 % CI: 1.07–1.97) (Table 3). In analyses adjusting for age at first sex, race/ethnicity, gender, age, mother/primary female caretaker’s education, and Wave III low functional income status in the past year the association between crack-cocaine use and two or more partnerships remained (adjusted prevalence ratio (APR): 1.54, 95 % CI: 1.38–1.71), but the association between injection drug use and two or more partnerships weakened and lost significance (APR: 1.28, 95 % CI: 0.93–1.77). In analyses adjusting for age at first sex, socio-demographic factors, and alcohol and other drug use, the association between crack-cocaine use and two or more partnerships weakened considerably but appeared to remain (APR: 1.19, 95 % CI: 1.06–1.34), while the association between IDU and the outcome weakened and was no longer significant.

Non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs also were much more likely than non-users to report having four or more sex partnerships in the past year (crack-cocaine PR: 2.59, 95 % CI: 2.19–3.06; IDU PR: 1.95, 95 % CI: 1.15–3.29). In analyses adjusting for age at first sex and socio-demographic factors, moderate to strong associations appeared to remain between non-injection crack-cocaine use and four or more partnerships (APR: 2.13, 95 % CI: 1.79–2.53) and between injection drug use and four or partnerships (APR: 1.66, 95 % CI: 0.98–2.82). In models adjusting for age at first sex, socio-demographic factors, and alcohol and other drug use, the association between non-injection crack-cocaine use and four or more partnerships remained (APR: 1.46, 95 % CI: 1.18–1.81), but the association between injection drug use and four or partnerships weakened and lost significance.

In both unadjusted and analyses adjusted for age at first sex, socio-demographic factors, and alcohol and other drug use, weak associations were observed between non-injection crack-cocaine and injection drug use and inconsistent condom use in the previous year (crack-cocaine APR: 1.09, 95 % CI: 1.05–1.13; IDU APR: 1.12, 95 % CI: 1.02–1.22).

Non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs were much more likely to report having sex with an STI-infected partner than non-users (crack-cocaine PR: 1.62, 95 % CI: 1.31–2.00; IDU PR: 2.44, 95 % CI: 1.48–4.01). In analyses adjusting for age at first sex and socio-demographic factors, the associations between non-injection crack-cocaine and injection drug use and sex with an infected partner generally remained (crack-cocaine APR: 1.63, 95 % CI: 1.29–2.06; IDU APR: 2.24 (1.22–4.10)). In analyses adjusting for age at first sex, socio-demographic factors, and alcohol and other drug use, the associations weakened and were no longer statistically significant.

Associations: Drug Use Category and Biologically-Confirmed STI

In unadjusted analyses, there were no significant associations between either non-injection crack-cocaine or injection drug use and having a biologically-confirmed STI (Table 3). However, in analyses adjusting for age at first sex, race/ethnicity, gender, age, mother/primary female caretaker’s education, and Wave III low functional income status in the past year both non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs were much more likely to have a biologically-confirmed STI than non-users of either drug (crack-cocaine APR: 1.64, 95 % CI: 1.16–2.31; IDU APR: 2.62, 95 % CI: 1.29–5.33). The unadjusted estimate was strongly confounded by race/ethnicity given the strong association between race/ethnicity and STI, with African Americans disproportionately infected, and between race/ethnicity and drug use, with African Americans less likely than other race/ethnic groups to be drug users. When race/ethnicity was removed from the adjusted model, the PRs decreased from 1.64 to 1.06 (95 % CI: 0.74–1.52) for crack-cocaine and from 2.62 to 1.66 (95 % CI: 0.81–3.43) for IDU, highlighting the important confounding effect of this variable. Fully-adjusted models that included controls for age at first sex, socio-demographic factors, and alcohol and other drug use indicated moderate associations between non-injection crack-cocaine and biologically-confirmed STI (crack-cocaine APR: 1.55, 95 % CI: 1.03–2.33), though the association between IDU and STI weakened and was no longer statistically significant (APR: 2.10, 95 % CI: 0.80–5.53).

Evaluation of Potential Mediators of Associations between Drug Use Category and STI

We sought to evaluate whether the high levels of STI observed among crack-cocaine users and IDUs could be attributed to sexual risk behaviors including multiple partnerships or consistent condom use or to elevated risk of links to high-risk networks as indicated by sex with an STI-infected partner. The association between non-injection crack-cocaine use and STI in models adjusted for age at first sex and socio-demographic characteristics (APR: 1.64, 95 % CI: 1.16–2.31; Table 3) did not materially change when further adjusting for indicators of multiple partnerships, inconsistent condom use, and sex with an STI-infected partner in the past year (APR: 1.59, 95 % CI: 1.08–2.34). Hence, the analyses suggested that these sexual risk indicators, as measured in Add Health, did not explain the moderate elevations in STI levels observed among non-injection crack-cocaine users.

The association between IDU and STI when adjusting for age at first sex and socio-demographic factors (APR: 2.62, 95 % CI: 1.29–5.33) was weakened somewhat but essentially remained when further adjusting for multiple partnership and inconsistent condom use variables (APR: 2.34, 95 % CI: 1.06–5.17). When a separate model was estimated that included age at first sex, socio-demographic factors, multiple partnership indicators, inconsistent condom use, and the addition of sex with an STI-infected partner, the association weakened by 20 % and was no longer significant (APR: 1.88, 95 % CI: 0.75–4.73). The analyses suggested that elevated risk among IDUs is more likely attributed to elevated risk of sex with infected partners than to elevated levels of multiple partnerships and inconsistent condom use.

Discussion

Among young adults in the US, in analyses adjusting for age at first sex and socio-demographic factors, injection drug use was independently associated with over twice the prevalence of biologically-confirmed STI, and non-injection crack-cocaine use was associated with moderate elevations in infection. While prior studies have documented the association between both non-injection and injection drug use and STI [5, 10, 15, 16], existing research has been somewhat limited by small sample size, restricted geographic scope, and focus on specific racial/ethnic populations. The current study documents high levels of STI among both non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs at the national level across race and gender sub-populations. The findings provide further support for the call that both non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs constitute priority populations for STI testing, treatment, and prevention interventions.

Our findings highlight the high vulnerability of IDUs to STI that has been observed previously [15–17]. While use of injection drugs may contribute to risk-taking that increases STI risk, elevated partnership levels among IDUs, in part due to trading sex for money or drugs, are well documented [3]. In the context of documenting high HSV-2 infection levels among IDUs in New York City, Des Jarlais et al. (2009) indicated that sexual transmission likely plays an important role in the transmission of HIV among IDUs. The study suggested that the role of sexual HIV transmission among IDUs may be underestimated due to limitations of the system used by CDC to classify causes of HIV cases [16]. Our findings provide further support for the need to consider expanding the CDC classification system to include a combined category of IDU and high-risk heterosexual sex so that the potential for sexual transmission among IDUs is documented. In addition, our findings highlight a need to emphasize both safer sex as well as safer injection practices in HIV prevention programs designed for IDUs [15, 17].

This study assessed the degree to which sexual risk behaviors including multiple partnerships and inconsistent condom use and/or sex with an STI-infected partner may mediate the relationship between drug use and STI. Our analyses suggested that elevated STI levels among IDUs were less likely due to elevations in multiple partnerships or inconsistent condom use, but, rather, due to elevated risk of sex with infected partners, a proxy for involvement in a high-risk sexual network. Prior studies also have indicated that IDUs experience elevated STI/HIV risk due to involvement in high-risk networks [6, 15]. Our results indicate that STI/HIV prevention messages targeting IDUs must emphasize their disproportionate risk of contact with someone who is infected and hence the importance of consistent condom use. Though IDUs likely face high infectious disease risk as a result of their involvement in high-risk social and sexual networks, prior research has indicated that IDU risk networks also may serve as important platforms for dissemination of STI/HIV control and prevention programs [46].

Non-injection crack-cocaine use was a stronger and more consistent correlate of elevated partnership levels than injection drug use, as has been observed in prior studies [3–8]. Crack-cocaine use is associated with higher levels of disinhibition and impulsivity, factors that drive sex risk, compared with use of other drugs such as opiates [8]. While non-injection crack-cocaine use was associated with both sexual risk behaviors and STI, our analyses failed to demonstrate that the sexual risk indicators, as measured in Add Health, accounted for the elevations in STI observed among non-injection crack-cocaine users. It is possible that sexual risk variables were not accurately measured in Add Health. Different indicators of elevated partnership levels, unprotected sex, and/or sex with infected partners may mediate the association between non-injection crack-cocaine user and STI. Nonetheless, robust associations between non-injected crack-cocaine use and both risk behaviors and infection suggest that prevention and treatment of crack-cocaine use, an important public health concern in itself, may reduce the high levels of partnership exchange levels that drive STI/HIV epidemics.

We observed high levels of polydrug use among non-injection crack-cocaine users and IDUs. Adjusted analyses suggested that sexual risk among crack-cocaine users and IDUs, in part, may be due to high levels of alcohol and other drug use in this population. Of particular note is the high level of crystal methamphetamine use observed among both non-injection crack/cocaine users and IDUs, given the strong consistent association between methamphetamine use and sexual risk taking [47–51]. The current study highlights the need for sexual risk reduction interventions for injectors and non-injectors to address polydrug use.

Conduct of research on drug use and STI in a general population sample presents limitations. Selection bias may have resulted if the school-based sampling frame omitted the adolescents who were at greatest risk of injection drug and crack-cocaine use because they were not enrolled in school; hence, the sample of Add Health respondents who reported use of these drugs may not represent other drug-using populations. In addition, because injection drug use is an uncommon event in the general population, despite the large Add Health sample, we did not have an adequate number of IDUs to enable comparison between IDUs who did versus who did not use crack-cocaine, a limitation given prior research has suggested that IDUs who used crack-cocaine have a higher risk of STI/HIV-related behaviors than non-crack-using IDUs [6, 7]. Another limitation with respect to assessment of drug use in Add Health is that, given the general nature of questions that assessed injection drug use—in which respondents were asked if they had ever injected any illegal drug, such as heroin or cocaine—we cannot know which drugs were injected in the sample. In addition, the indicators of sexual risk-taking included in this analysis present limitations. Self-reported measures of STI, sex with infected partners, and sexual risk behaviors are known to suffer from recall and self-presentation bias. To most effectively measure sex with an STI-infected partner, for example, we would need to conduct a network study in which we measured biologically confirmed current infection for index cases and partners. Since such network data are not available in Add Health, we used the indicator of sex with a partner who had ever had an STI as a proxy measure. It is possible that a biomarker of sex with an infected partner may have suggested that this variable accounted for elevated levels of STI among crack-cocaine users as well as in IDUs. In addition, indicators of multiple partnerships were included, though STI risk would be minimal if condoms were used consistently within these partnerships. However, we elected to examine multiple partnerships as an indicator of risk because the rate of partnership exchange is an important STI determinant. Further, because inconsistent condom use is commonly measured in drug using populations [3], drug users in this dataset who report multiple partnerships likely face elevated STI risk.

This study documents high STI/HIV risk among both non-injection crack/cocaine users and IDUs. Given the apparent roles of both non-injection and injection drug use in the current STI/HIV epidemics, these populations should be prioritized for further development, evaluation, and dissemination of STI/HIV treatment and prevention interventions. The results highlight the particular vulnerability of IDUs to sexually transmissible infection and suggest that sexual transmission of HIV transmission may play a greater role in the epidemic among IDUs than is currently indicated.

References

CDC. Trends in Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States: 2009 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia and Syphilis Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009.

CDC. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/.

Celentano DD, Latimore AD, Mehta SH. Variations in sexual risks in drug users: emerging themes in a behavioral context. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5(4):212–8.

Ross MW, Williams ML. Sexual behavior and illicit drug use. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2001;12:290–310.

Hwang LY, Ross MW, Zack C, Bull L, Rickman K, Holleman M. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and associated risk factors among populations of drug abusers. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(4):920–6.

Booth RE, Kwiatkowski CF, Chitwood DD. Sex related HIV risk behaviors: differential risks among injection drug users, crack smokers, and injection drug users who smoke crack. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58(3):219–26.

McCoy CB, Lai S, Metsch LR, Messiah SE, Zhao W. Injection drug use and crack cocaine smoking: independent and dual risk behaviors for HIV infection. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(8):535–42.

Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Daughters SB, Curtin JJ. Differences in impulsivity and sexual risk behavior among inner-city crack-cocaine users and heroin users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77(2):169–75.

Khan MR, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, et al. Social and behavioral correlates of sexually transmitted infection- and HIV-discordant sexual partnerships in Bushwick, Brooklyn, New York. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(4):470–85.

Friedman SR, Flom PL, Kottiri BJ, et al. Drug use patterns and infection with sexually transmissible agents among young adults in a high-risk neighbourhood in New York City. Addiction. 2003;98(2):159–69.

Sena AC, Muth SQ, Heffelfinger JD, O’Dowd JO, Foust E, Leone P. Factors and the sociosexual network associated with a syphilis outbreak in rural North Carolina. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(5):280–7.

Ellen JM, Langer LM, Zimmerman RS, Cabral RJ, Fichtner R. The link between the use of crack cocaine and the sexually transmitted diseases of a clinic population. A comparison of adolescents with adults. Sex Transm Dis. 1996;23(6):511–6.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, et al. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(5):616–23.

Miller M, Liao Y, Wagner M, Korves C. HIV, the clustering of sexually transmitted infections, and sex risk among African American women who use drugs. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(7):696–702.

Plitt SS, Sherman SG, Strathdee SA, Taha TE. Herpes simplex virus 2 and syphilis among young drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(3):248–53.

Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, McKnight C, Hagan H, Perlman D, Friedman SR. Using hepatitis C virus and herpes simplex virus-2 to track HIV among injecting drug users in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101(1–2):88–91.

Strathdee SA, Sherman SG. The role of sexual transmission of HIV infection among injection and non-injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4 Suppl 3):iii7–14.

Kral AH, Bluthenthal RN, Lorvick J, Gee L, Bacchetti P, Edlin BR. Sexual transmission of HIV-1 among injection drug users in San Francisco, USA: risk-factor analysis. Lancet. 2001;357(9266):1397–401.

Lindenburg CE, Krol A, Smit C, Buster MC, Coutinho RA, Prins M. Decline in HIV incidence and injecting, but not in sexual risk behaviour, seen in drug users in Amsterdam: a 19-year prospective cohort study. AIDS. 2006;20(13):1771–5.

CDC. STD Health Equity. 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/std/health-disparities/default.htm. Accessed 28 February 2011.

SAMHSA. Results from the 2009 national survey on drug use and health: volume I. Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, SAMHSA, 2010.

SAMHSA. The NSDUH report: injection drug use. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, SAMHSA, 2003.

Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W Jr. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6–10.

CDC. Trends in reportable sexually transmitted diseases in the United States, 2006: National Surveillance Data for Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis, 2007.

Nusbaum MR, Wallace RR, Slatt LM, Kondrad EC. Sexually transmitted infections and increased risk of co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2004;104(12):527–35.

Westrom L, Eschenbach D. Pelvic inflammatory disease. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Mårdh P, editors. Sexually transmitted diseases, 3rd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; pp. 783–809.

Schulz KF, Cates W Jr, O’Mara PR. Pregnancy loss, infant death, and suffering: legacy of syphilis and gonorrhoea in Africa. Genitourin Med. 1987;63(5):320–5.

Gust DA, Levine WC, St Louis ME, Braxton J, Berman SM. Mortality associated with congenital syphilis in the United States, 1992–1998. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):E79–89.

Marai W. Lower genital tract infections among pregnant women: a review. East Afr Med J. 2001;78(11):581–5.

Cohen MS. HIV and sexually transmitted diseases: lethal synergy. Top HIV Med. 2004;12(4):104–7.

Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75(1):3–17.

Cohen MS. Sexually transmitted diseases enhance HIV transmission: no longer a hypothesis. Lancet. 1998;351(Suppl 3):5–7.

Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Trans Dis. 1992;19(2):61–77.

Cohen MS, Hoffman IF, Royce RA, et al. Reduction of concentration of HIV-1 in semen after treatment of urethritis: implications for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV-1. AIDSCAP Malawi Research Group. Lancet. 1997;349(9069):1868–73.

Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth. Accessed August 2, 2012.

Udry JR. References, instruments, and questionnaires consulted in the development of the add health in-home adolescent interview. Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/refer.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2012.

Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–32.

Chantala K, Tabor J. Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the add health data. Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/guides/weight1.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2012.

Sieving RE, Beuhring T, Resnick MD, et al. Development of adolescent self-report measures from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(1):73–81.

Cohen M, Feng Q, Ford CA, et al. Biomarkers in wave III of the add health study. Carolina Population Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/faqs/aboutdata/index.html/biomark.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2012.

Watson EJ, Templeton A, Russell I, et al. The accuracy and efficacy of screening tests for Chlamydia trachomatis: a systematic review. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51(12):1021–31.

Johnson RE, Green TA, Schachter J, et al. Evaluation of nucleic acid amplification tests as reference tests for Chlamydia trachomatis infections in asymptomatic men. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(12):4382–6.

Koumans EH, Johnson RE, Knapp JS, St Louis ME. Laboratory testing for Neisseria gonorrhoeae by recently introduced nonculture tests: a performance review with clinical and public health considerations. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(5):1171–80.

McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940–3.

Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–6.

Friedman SR, Bolyard M, Maslow C, Mateu-Gelabert P, Sandoval M. Harnessing the power of social networks to reduce HIV risk. Focus. 2005;20(1):5–6.

Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27(3):253–62.

Gonzales R, Mooney L, Rawson RA. The methamphetamine problem in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 31:385–398.

Shrem MT, Halkitis PN. Methamphetamine abuse in the United States: contextual, psychological and sociological considerations. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(5):669–79.

Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. West J Med. 1998;168(2):93–7.

Molitor F, Bell RA, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Predictors of failure to return for HIV test result and counseling by test site type. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(1):1–13.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant Longitudinal Study of Substance Use, Incarceration, and STI in the US (Maria Khan, PI, R03 DA026735). This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01- HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgement is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. People interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) under the auspices of the Data Sharing for Demographic Research (DSDR) archive (http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/DSDR/access/add-health.jsp).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.R., Berger, A., Hemberg, J. et al. Non-Injection and Injection Drug Use and STI/HIV Risk in the United States: The Degree to which Sexual Risk Behaviors Versus Sex with an STI-Infected Partner Account for Infection Transmission among Drug Users. AIDS Behav 17, 1185–1194 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0276-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0276-0