Abstract

Too many people with HIV have left the job market permanently and those with reduced work capacity have been unable to keep their jobs. There is a need to examine the health effects of labor force participation in people with HIV. This study presents longitudinal data from 1,415 HIV-positive men who have sex with men taking part in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Generalized Estimating Equations show that employment is associated with better physical and mental health quality of life and suggests that there may be an adaptation process to the experience of unemployment. Post hoc analyses also suggest that people who are more physically vulnerable may undergo steeper health declines due to job loss than those who are generally healthier. However, this may also be the result of a selection effect whereby poor physical health contributes to unemployment. Policies that promote labor force participation may not only increase employment rates but also improve the health of people living with HIV.

Resumen

Demasiadas personas que viven con VIH han abandonado permanentemente el mercado laboral y aquellas con reducida capacidad de trabajo no han podido mantener sus puestos de trabajo. Es necesario evaluar los efectos de la participación laboral sobre la salud en personas que viven con VIH. Este estudio presenta datos longitudinales de 1,415 hombres VIH-positivos que tienen sexo con hombres, recabados del Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Ecuaciones de Estimación Generalizadas mostraron que el empleo esta asociado con mejor calidad de vida en relacion a la salud fisica y mental y ademas sugiere un proceso de adaptación a la experiencia de desempleo. Análisis posteriores y provisionales también sugieren que las personas físicamente mas vulnerables pueden sufrir caidas mas pronunciadas de la salud debido a la pérdida de empleo, comparados con aquellos que generalmente estan mas saludables. Sin embargo, esto también puede ser el resultado de un efecto de selección mediante el cual una salud física disminuida contribuye al desempleo. Las politicas que promueven la participación en el mercado laboral no solo podrian aumentar las tasas de empleo, sino también mejorar la salud de las personas que viven con VIH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the general population, the harmful effects of unemployment on health are well-known [1, 2]. Longitudinal studies have shown the detrimental effects of unemployment on depression [3], cardiovascular disease [4], and mortality [5]. The body of evidence linking unemployment with declines in health is sufficiently robust to suggest a portion of the association is causal [1, 6]. Correspondingly, a smaller body of work has shown the beneficial effects of return to work on alleviating depression [7], psychological distress [8], psychiatric symptoms [9], and increasing survival [10]. A recent systematic review of longitudinal studies showed the positive effects of return to work on health in a variety of populations, times and settings [11].

Participation in employment provides workers with an income, structured time and regular activity, regular contact with people outside the immediate family, connection with goals that transcend their own, and identity and position within society [12]. The evidence for the effects of employment on health in people living with HIV is limited despite the high prevalence of non-participation in paid employment, which ranges from 45 to 62 % [13, 14]. A few cross-sectional studies have shown an association between employment status and health-related quality of life in people with HIV [15–17]. One cross-sectional study conducted in the US found that employed participants reported higher quality of life relative to unemployed participants after controlling for disease severity [15]. Another cross-sectional study conducted in Canada found that the strongest predictor of five health-related quality of life subscales was employment status, after controlling for socioeconomic characteristics and clinical markers [16]. This study, by adjusting for income and education, supports the idea that employment may provide health-protecting effects over and above current income and past educational opportunities. A more recent Canadian cross-sectional study found that employment status was strongly related to both physical and mental health quality of life after controlling for clinical covariates, including sociodemographic factors, HIV-disease markers and neurocognitive function [17]. This study found that the positive association between employment status and quality of life was stronger for physical health than mental health, suggesting an adaptation to the experience of unemployment. To our knowledge, the only longitudinal study that has examined the association between employment and health in HIV was conducted in France over a median follow-up of 2.5 years (range 5.3 months–6.5 years) [18]. This study included 319 HIV-positive participants and found that people working in a form of precarious employment (temporary employment) were 2.5 times more likely to be hospitalized or die relative to those with stable employment. Interestingly, the increased risk of hospitalization or death for those who were unemployed was not statistically significant.

The objective of this study is to examine the association between employment and health-related quality of life over a ten-year period in a large longitudinal cohort of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. We hypothesized that employment would have a positive impact on both physical and mental health quality of life, independent of clinical and sociodemographic confounders. We also expected that employment would have a more pronounced association with physical health than mental health quality of life.

Methods

Participants

This study analyzed data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). The MACS is an ongoing longitudinal observational study designed to assess the natural and treated history of HIV disease among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States. The initial cohort consisted of 4,954 MSM (≥18 year-old HIV-negative and HIV-positive men), who were recruited between 1984 and 1985 at four sites (Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles and Pittsburg). A second recruitment wave took place between 1987 and 1991, where 668 MSM were enrolled to increase enrollment of minorities (primarily African-American MSM) and a third recruitment wave was conducted between 2001 and 2003 (also focusing on minorities and younger MSM) resulting in 1,351 additional participants [19]. MACS participants are followed every 6 months with questionnaire-based interviews, physical examinations, medical history reviews and laboratory testing. Research ethics approvals were obtained at each site through their respective Institutional Review Boards (see Kaslow et al. [20], and Detels et al. [21], for a detailed description of the cohort).

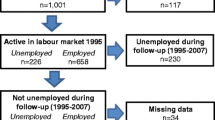

The present study analyzed data from HIV-positive MSM who participated in the MACS from 1996 until 2006. This dataset contained data that had been collected twice per year for a maximum of 20 visits on 1,523 HIV-positive MSM. We used all available data contributed by participants who were HIV-positive at the beginning of the observation period and all observations from seroconverters once they became HIV-positive. We selected these participants because we were interested in the experience of living with HIV after the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). We included in the analyses those men who also provided data on the main predictor variable (employment status) and the outcome (health-related quality of life). Of the maximum number of participants who contributed data in most variables (1,523 participants), we included 1,415 participants (10,923 observations) in our multivariate analyses. There were no significant differences on key baseline demographics between those who were excluded (n = 108) and those who were included in the final multivariate models (n = 1,415).

Measures

The following variables were considered as possible predictors of health-related quality of life, based on available data and conceptual models previously used by the MACS:[22, 23] Individual characteristics (sociodemographic and individual risk behaviors), clinical indicators (biological markers, HIV-related medication use and insurance, and clinical outcome variables) and social support.

Health-Related Quality of Life

The SF-36 is a multipurpose survey that measures self-reported health-related quality of life. The 36 items combine to create eight domains of health: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores reflecting higher health-related quality of life within the domain [24]. We computed both the physical component score (PCS) and the mental component score (MCS) following the developers’ instructions. We transformed both summary scores (PCS and MCS) to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. This means that scores below (or above) 50 indicate worse (or better) health-related quality of life compared to the reference population (i.e., the 1998 General US population) [25]. The results of several studies support the reliability and validity of the SF-36 in HIV-positive populations [26, 27].

Sociodemographic Factors

We dichotomized race/ethnicity into White-non-Hispanic versus other (White-Hispanic, Black-Hispanic/non-Hispanic, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, other Hispanic) and employment status into employed (working full-time or part-time) versus non-employed (unemployed-seeking work, unemployed-not seeking work, student, retired, or on disability). Age and education were measured in years and treated as continuous variables. Individual gross income was categorized in $10,000 increments from <$10,000 to >$60,000 and was also treated as a continuous variable.

Individual Risk Factors

We dichotomized injection drug use into never versus former and current (due to small number of current users), drinking pattern in the past 6 months into heavy/binge (>14 drinks/week) versus none, light (<3 drinks/week) and moderate (3–13 drinks/week), and smoking status into current smoker versus never smoked and past smoker.

Biological Markers

Laboratory markers were measured at each visit. Plasma HIV RNA levels were determined using the Roche ultrasensitive assay (lower limit of detection of 50 copies/ml). We dichotomized HIV viral load as undetectable (<50 copies/ml) or detectable (≥50 copies/ml). CD4+ lymphocyte counts were measured using the standardized flow cytometry and analyzed as a continuous variable after a natural log transformation.

HIV-Related Medication Use and Insurance

Type of antiretroviral therapy was dichotomized into no therapy, monotherapy and combination therapy versus combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Health insurance coverage was dichotomized into uninsured and insured (coverage by an HMO, group and individual private insurance such as Blue Cross and CIGNA, Medicaid, Medicare, Veteran’s Administration/Armed Forces, CHAMPUS/CHAMP-VA insurance or other insurance coverage).

Clinical Outcome Indicators

HIV-related symptoms included the number of symptoms experienced for at least 3 consecutive days since the last visit (i.e., past 6 months) out of nine symptoms commonly related to HIV (i.e., persistent fatigue, persistent/recurring fever, persistent/frequent/unusual headache, new skin condition/rash/infection, tender/enlarged glands/lymph nodes, diarrhea, drenching night sweats, unusual bruise/bump/skin discoloration that lasted at least 2 weeks, and unintentional weight loss ≥10 lb). Hospitalization refers to the number of hospitalization incidents experienced since the last visit (i.e., in the past 6 months).

Social Support

Number of people available to talk to from the self-administered questionnaire was selected as a representative indicator of social support and it was characterized as number of persons around to talk to: no one, only 1 person, 2 or 3 people, 4 or 5 people, 6 or more people.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the data using generalized estimating equations (GEE), which takes into account the correlations among multiple observations and variable timing of observations within subjects [28]. This model allows inclusion of health-related quality of life values at each visit as well as current values of all variables examined in the GEE models. We used the exchangeable correlation structure, which assumes that the correlation between any two observations from the same individual is the same, irrespective of the length of the time interval [29]. The main objective of this approach was to determine the relationship between employment status and health-related quality of life, after controlling for potential sociodemographic and clinical confounders.

We identified predictor variables that we believed a priori to be associated with health-related quality of life based on theoretical frameworks and clinical experience [22, 23]. We fitted univariate GEE models for each of the two outcomes (physical and mental health quality of life) and each predictor variable to determine which variables were most strongly associated with each outcome. Based on the results of these univariate models, we selected a saturated model for each of the two outcomes that included the covariates that showed the strongest relationship with the particular outcome of interest (P-values < 0.10). When two covariates were highly correlated (e.g., CD4 counts and viral load), we selected the variable that showed the strongest association with the outcome of interest. The final models included only those predictors with significant associations with the outcomes (P-values < 0.05) making sure that potential effect modifiers did not affect the coefficient of employment status. The final models excluded visits with missing data on any covariate in the model.

The final stage in our modeling strategy was the post hoc application of a group-based trajectory model to examine the effect of job loss and return to work events on health-related quality of life [30, 31]. This univariate model assumes that there are unobserved subpopulations of participants with differently shaped-trajectories of the outcomes over time (i.e., the trajectory groups in this study describe clusters of participants with different trajectories of quality of life scores over time). We wanted to evaluate whether a subset of participants belonging to the return to work and the job loss employment groups were related to the quality of life trajectory groups generated by the group-based trajectory model. We decided to concentrate on job loss and return to work because we were interested in examining change in employment status. More specifically, we included in these analyses only those participants from the return to work and job loss groups who provided data before and after the change in employment status. Thus, we excluded those return to work and job loss participants that showed a change in employment status on the last follow-up visit in the observation period.

Results

Participants

The study sample included a total of 1,415 HIV-positive men who have sex with men. The characteristics of the participants at their first study visit in the period of interest (1996–2006) are presented in Table 1. The majority of the participants were non-Hispanic white (58 %), employed (63 %), with a mean age of 42 years and 15 years of education. More than half the sample (56 %) had an income below US$30,000, although most participants (85 %) had some form of health insurance coverage. Only about one quarter (27 %) had an undetectable viral load and close to half the sample were receiving cART (44 %) at the first study visit. The physical and mental health quality of life scores of the study sample were below that of the reference population (i.e., US 1998 general population).

The observation period spanned 10 years (1996–2006) with two visits per year. Participants contributed data for a median of 6 visits (IQR = 4–14). The employment groups throughout the study period consisted of 41 % continuously employed individuals, 4 % who returned to work, 22 % intermittently employed, 9 % who lost their jobs, and 24 % who were continuously unemployed. The 1,415 individuals contributed a total of 7,298 person-years and 68 % of those (4,963 person-years) while on cART. More than half (56 %) of the total person-years was contributed by participants while their viral load was detectable.

Associations Between Sample Characteristics and Health-Related Quality of Life

We fitted single-predictor (unadjusted) GEE models for both physical and mental health quality of life (Table 2). We found that employment status was strongly associated with both physical (β = 8.66, 95 % CI 7.77–9.56) and mental health quality of life (β = 5.02, 95 % CI 3.90–6.15). All the remaining predictor variables, except race/ethnicity, education and injection drug use, were significantly associated with either or both quality of life summary scores.

We analyzed the association between participant characteristics and quality of life scores using multivariate (adjusted) GEE models (Table 2). Higher physical health quality of life was associated with being employed, younger age, higher income, higher CD4 cell counts, absence of HIV symptoms, and not requiring hospitalization. Higher mental health quality of life was associated with being employed, older age, non-smoking, absence of HIV symptoms, and a higher level of social support. Employment status remained significantly associated with better physical health quality of life scores by 3.17 points on a 100-point scale (95 % CI 2.56–3.79) and with better mental health quality of life scores by 2.21 points (95 % CI 1.59–2.83), after controlling for potential confounders. Employment status had a stronger relationship with physical health than mental health quality of life.

We also examined whether the regression coefficients for employment status were overestimated in theses analyses due to the presence of items in the outcome measure that inquire about the relationship between work and health. After removing the SF-36's role physical and role emotional subscales, we found that the regression coefficients for employment status were smaller for both physical and mental health quality of life, but they remained significantly associated with both summary scores and the resulting models were unaffected.

Employment Trajectories (Return to Work and Job Loss) and Physical Health Quality of Life

Only 121 out of the 198 participants from the return to work and job loss groups were included in the post hoc, group-based trajectory analysis. The remaining 77 participants were excluded either because the change in employment status occurred on the last follow-up visit (n = 34) or at the end of the observation period (n = 43). The proportions of both the return to work and job loss groups were similar between those participants who were excluded and those who were included in this analysis.

Figures 1 and 2 provide average trend lines for the return to work and the job loss groups. The plots suggest that the physical and mental health quality of life scores, on average, respond differently to the change in employment status. The physical health quality of life score shows little or no increase over the course of the study for the return to work group and a sharp drop around the employment transition for the job loss group. Conversely, the mental health quality of life score shows a stable or slight decline over the course of the study for the job loss group and a steeper increase around the employment transition for the return to work group.

Figure 3 provides expected (dashed) and observed (solid) trajectories for physical health quality of life resulting from fitting a two-group trajectory model with cubic trajectories for each group (The model for mental health quality of life failed to reach statistical significance; graph not shown). The results of the group-based trajectory modeling indicate that the population experiencing a change in employment status could be classified into two trajectory groups (see also Table 3): (1) Trajectory group 1: 40 % of the participants started the observation period with low levels of physical health and experienced a sharp drop in scores after the employment transition occurred; (2) Trajectory group 2: 60 % of the participants were classified as experiencing a high level of physical health that only slightly declined with time. Interestingly, the job loss group was evenly distributed in these trajectories (i.e., about half of the participants in the job loss group were classified into the trajectory group 1 and half into the trajectory group 2). However, the return to work group had a different distribution (i.e., about one quarter of the participants in the return to work group were classified into the trajectory group 1 and three quarters into the trajectory group 2). The Wald test for the employment group parameter estimate was significant [χ2 (1) = 5.5, P = 0.02] suggesting that there is a statistically significant relationship between the trajectory group and the employment group classifications (This Wald test is equivalent to the Chi-square goodness-of-fit test applied to the data presented in Table 3.) This result suggests that the job loss group is not a homogeneous group. Half of this group started with high levels of physical health, which remained high as they transitioned through the job loss, while the other half started with low levels of physical health and experienced a steeper decline in health as they transitioned through the job loss. Unfortunately, this post hoc application of the group-based trajectory model is a univariate analysis and as a result we were unable to adjust for potential confounders or include interaction terms.

Discussion

This longitudinal study found that employment was associated with better physical and mental health quality of life in HIV-positive men who have sex with men, after controlling for clinical and other sociodemographic characteristics. This finding is consistent with previous North-American cross-sectional studies that have reported an association between employment and health-related quality of life in people with HIV [15–17]. To our knowledge, the only other longitudinal study to date that has examined the impact of employment on health in HIV found that, over a median follow-up of 2.5 years, patients with temporary employment had an increased risk of hospitalization or death relative to those with stable employment [18]. However, although unemployed participants were more likely to be hospitalized or die relative to those with stable employment, this risk was not significant. The authors proposed that this counterintuitive finding might be a consequence of the structure of benefits in France that may favor the unemployed over people working in precarious conditions [18]. In partial support of this notion, research in the general population suggests that working in precarious employment––job insecurity in particular––may be as harmful to health as job loss [32, 33]. We have shown in a cross-sectional study, conversely, that job security offers additional mental health benefits over and above participation in employment for men living with HIV [34].

We also found that employment was associated with greater differences in physical health than mental health quality of life. This finding is also in agreement with our previous cross-sectional study with people with HIV, which suggested that people may show a degree of psychological adaptation to the experience of unemployment after some time out of the labor force [17]. This adaptation process may be more clearly identified by the mental health component of quality of life and may contribute to make the association between employment and physical health more salient. This observation would be consistent with set-point theories that propose that people’s subjective well-being is initially affected in response to stressful events, but then tends to return to baseline over time. There is evidence to support this adaptation process related to the experience of unemployment in the general population [35], although not consistently [36, 37]. Independent of this finding, the association of employment status with mental health quality of life is clinically significant.

Our study also found preliminary evidence suggesting that men with HIV who suffer poor physical health in general may undergo steeper declines in physical health due to job loss than those who are generally healthier. This result is suggestive of anticipatory reactions to the experience of unemployment as physical health starts declining within 6 months prior to job loss. Unfortunately, we did not have data on job insecurity to examine the health effects related to the threat of losing one’s job. An alternative explanation would be that declining health is in fact the precursor to job loss. Participants may have been experiencing health problems that compromised their employment status, which further resulted in health declines. Even though this finding requires further investigation, those in better physical health seem to be more resilient to the negative impact of unemployment and appear to be able to avoid sharper declines in health as a result of job loss. We were, however, unable to show this association for mental health.

In this study, the overall level of participation of HIV-positive men in the job market was low. Less than half of the participants remained employed and a quarter of the participants remained out of the labor force for the duration of the observation period. This study also showed that a fifth of the participants moved in and out of jobs, suggesting a fair level of employment instability. We lacked data on the unemployed participants’ needs or levels of motivation to go back to work, or the barriers that this group might have faced in their attempts to return to work. However, a number of studies have highlighted the negative effects of various systemic barriers on the ability of people with HIV to remain employed or go back to work, such as the structure of disability supports, uncertainty of disease progression, workplace discrimination and lack of workplace accommodations [38–40]. Other studies have reported on the independent contribution of demographic and clinical factors such as age, gender, education, depression and neuropsychological functioning as barriers to returning to work [41–44]. This increasing body of research suggests that––unless medically indispensable––people with HIV and clinicians should balance the advantages and disadvantages of leaving the workforce. The decisions to leave the workforce should be carefully planned as there is a high risk that the individual may not be able to return to work and be chronically left out of the labor force [40].

The strengths of this study include the longitudinal evaluation (over a ten-year observation window) of the association between employment and health in a large cohort of HIV-positive men who have sex with men that included adjustment for a wide range of potential sociodemographic and clinical confounders. A limitation of this study refers to residual confounding as data on variables that may increase our understanding of the mechanisms behind the health benefits of employment were not available for analysis. We did not have information on the psychosocial work conditions of employed participants or detailed information on factors related to structural barriers to employment, such as HIV-related stigma or workplace discrimination. We also lacked data on the reasons for separation from the labor market and we suspect that whether people decided to leave work voluntarily or as a result of illness, layoff or termination may have different health implications.

Another limitation was related to the post hoc application of the group-based trajectory analysis, which included small sample sizes and did not allow to control for potential confounders. This post hoc analysis, however, suggested that people who are physically vulnerable may experience greater declines in health associated with job loss––relative to those who are generally healthier––and we believe that this observation should be investigated in future research. This preliminary finding also raises the issue of whether this observation is the result of a selection effect whereby poor physical health contributes to unemployment. Keeping in mind the important caveats associated with this post hoc analysis, it presents a viable hypothesis to be tested in future studies.

Lastly, this study was conducted with a population of HIV-positive men who have sex with men living in the US and this may raise concerns about whether these findings would be applicable to other HIV-positive populations. The results of this study are consistent with cross-sectional studies with less homogeneous populations from the US and Canada. We would however suspect that employment may have a differential health effect on men and women as men’s traditional role of being the primary bread winner may make the experience of losing a job more distressing for them. On the other hand, we would not expect to find fundamental differences between gay and straight men as both groups would generally have no expectation of financial dependence on partners or spouses (e.g., most gay couples would likely expect to live on two incomes).

The conceptual framework that situates employment status as a potential stressor that contributes to poor health assumes that employment precedes poor health, a situation that cannot be properly examined in cross-sectional studies. The longitudinal analyses presented in this paper, however, were not designed to establish the temporal sequence between change in employment status and its effect on health (e.g., time-lag analyses). Nonetheless, the results from the present study are less likely to be biased than those generated from cross-sectional analyses because the estimates produced by the GEE regression models incorporate both the between-subject effects (i.e., the difference between employed and non-employed individuals) and the within-subject effects (i.e., the within individual change in quality of life due to change in employment status). To put this in context, two-thirds of the participants came from the continuously employed or continuously unemployed groups (contributing data to assess the between-subject effect) and a third of the participants came from trajectories where employment change took place (contributing data to assess both the between-subject and the within-subject effects). Despite this limited assurance, the alternative selection explanation cannot be ruled out.

This research provided evidence that participation in the labor market is associated with better health and suggests that policies that focus on improving employment opportunities would have a positive impact on the health of people with HIV. Better disability policies may reduce some of the financial risks that people experience in their attempts to return to work or the stress associated with maintaining employment. Policy studies should be designed in a way that acknowledge the difficulties inherent in analyzing data where the structure of the benefit programs may create incentives for people with HIV to remain at work when their health is compromised––in order to maintain access to insurance––or disincentives to go back to work when their health improves––to avoid losing disability income or medication coverage. Policy research is needed to identify and address structural issues in the benefits and drug coverage programs that may be implicated in creating barriers for people with HIV to return to work or force them to stay at work when they need to go on disability.

References

Jin R, Shah C, Svoboda T. The impact of unemployment on health: a review of the evidence. J Public Health Policy. 1997;18:275–301.

Strully K. Job loss and health in the US labor market. Demography. 2009;46(2):221–46.

Price RH, Choi JN, Vinokur AD. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: how financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7(4):302–12.

Gallo WT, Teng HM, Falba TA, Kasl SV, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH. The impact of late career job loss on myocardial infarction and stroke: a 10 year follow up using the health and retirement survey. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(10):683–7.

Sullivan D, von Wachter T. Job displacement and mortality: an analysis using administrative data. Q J Econ. 2009;124(3):1265–306.

Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58(5):295–300.

Ginexi EM, Howe GW, Caplan RD. Depression and control beliefs in relation to reemployment: what are the directions of effect? J Occup Health Psychol. 2000;5(3):323–36.

Thomas C, Benzeval M, Stansfeld SA. Employment transitions and mental health: an analysis from the British household panel survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(3):243–9.

Bond GR, Resnick SG, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Bebout RR. Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(3):489–501.

Martikainen P, Valkonen T. Excess mortality of unemployed men and women during a period of rapidly increasing unemployment. Lancet. 1996;348(9032):909–12.

Rueda S, Chambers L, Wilson M, Mustard C, Rourke S, Bayoumi A, et al. Association of returning to work with better health in working-aged adults: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):541–56.

Jahoda M. Work, employment, and unemployment: values, theories, and approaches in social research. Am Psychol. 1981;36(2):184–91.

Burgoyne R, Saunders D. Quality of life among urban Canadian HIV/AIDS clinic outpatients. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(8):505–12.

Dray-Spira R, Gueguen A, Ravaud J, Lert F. Socioeconomic differences in the impact of HIV infection on workforce participation in France in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(3):552–8.

Blalock A, McDaniel J, Farber E. Effect of employment on quality of life and psychological functioning in patients with HIV/AIDS. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(5):400–4.

Worthington C, Krentz H. Socio-economic factors and health-related quality of life in adults living with HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:608–14.

Rueda S, Raboud J, Mustard C, Bayoumi A, Lavis J, Rourke S. Employment status is associated with both physical and mental health quality of life in people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2011;23(4):435–43.

Dray-Spira R, Gueguen A, Persoz A, Deveau C, Lert F, Delfraissy J, et al. Temporary employment, absence of stable partnership, and risk of hospitalization or death during the course of HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(2):190–7.

Silvestre A, Hylton J, Johnson L, Houston C, Witt M, Jacobson L, et al. Recruiting minority men who have sex with men for HIV research: results from a 4-city campaign. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1020–7.

Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR Jr. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126(2):310–8.

Detels R, Munoz A, McFarlane G, Kingsley LA, Margolick JB, Giorgi J, et al. Effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS and death in men with known HIV infection duration. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Investigators. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1497–503.

Liu C, Johnson L, Ostrow D, Silvestre A, Visscher B, Jacobson L. Predictors for lower quality of life in the HAART era among HIV-infected men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:470–7.

Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. 36-Item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Bjoner J, Turner-Bowker D, Gandeck B, Maruish M. User’s manual for the SF-36v2 health survey. 2nd ed. Lincoln: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2007.

Bing EG, Hays RD, Jacobson LP, Chen B, Gange SJ, Kass NE, et al. Health-related quality of life among people with HIV disease: results from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(1):55–63.

Riley ED, Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Clark RA, Moss AR, Wu AW. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 in HIV-infected homeless and marginally housed individuals. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(8):1051–8.

Liang K, Zeger S. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22.

Twisk J. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology: a practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Jones B, Nagin D, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29(3):374–93.

Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods. 1999;4(2):139–57.

Dekker SWA, Schaufeli WB. The effects of job insecurity on psychological health and withdrawal: a longitudinal study. Aust Psychol. 1995;30(1):57–63.

Broom D, D’Souza R, Strazdins L, Butterworth P, Parslow R, Rodgers B. The lesser evil: bad jobs or unemployment? A survey of mid-aged Australians. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:575–86.

Rueda S, Raboud J, Rourke S, Bekele T, Bayoumi A, Lavis J, et al. The influence of employment and job security on physical and mental health in HIV-positive patients: a cross-sectional analysis. Open Med. 2012 (in press).

Warr P, Jackson P. Adapting to the unemployed role: a longitudinal investigation. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(11):1219–24.

Lucas R, Clark A, Georgellis Y, Diener E. Unemployment alters the set point for life satisfaction. Psychol Sci. 2004;15(1):8–13.

Morrell S, Taylor R, Quine S, Kerr C, Western J. A cohort study of unemployment as a cause of psychological disturbance in Australian youth. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(11):1553–64.

Braveman B, Levin M, Kielhofner G, Finlayson M. HIV/AIDS and return to work: a literature review one-decade post-introduction of combination therapy (HAART). Work. 2006;27(3):295–303.

Martin DJ, Brooks RA, Ortiz DJ, Veniegas RC. Perceived employment barriers and their relation to workforce-entry intent among people with HIV/AIDS. J Occup Health Psychol. 2003;8(3):181–94.

Rabkin JG, McElhiney M, Ferrando SJ, Van Gorp W, Lin SH. Predictors of employment of men with HIV/AIDS: a longitudinal study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(1):72–8.

Dray-Spira R, Gueguen A, Lert F. Disease severity, self-reported experience of workplace discrimination and employment loss during the course of chronic HIV disease: differences according to gender and education. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65(2):112–9.

Dray-Spira R, Persoz A, Boufassa F, Gueguen A, Lert F, Allegre T, et al. Employment loss following HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapies. Eur J Pub Health. 2006;16(1):89–95.

Martin DJ, Arns PG, Batterham PJ, Afifi AA, Steckart MJ. Workforce reentry for people with HIV/AIDS: intervention effects and predictors of success. Work. 2006;27(3):221–33.

van Gorp WG, Rabkin JG, Ferrando SJ, Mintz J, Ryan E, Borkowski T, et al. Neuropsychiatric predictors of return to work in HIV/AIDS. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(1):80–9.

Acknowledgments

The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) includes the following: Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Joseph B. Margolick (Principal Investigator), Michael Plankey (Co-Principal Investigator), Barbara Crain, Adrian Dobs, Homayoon Farzadegan, Joel Gallant, Lisette Johnson-Hill, Ned Sacktor, Ola Selnes, James Shepard, Chloe Thio. Chicago: Howard Brown Health Center, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and Cook County Bureau of Health Services: John P. Phair (Principal Investigator), Steven M. Wolinsky (Principal Investigator), Sheila Badri, Craig Conover, Maurice O’Gorman, David Ostrow, Frank Palella, Ann Ragin. Los Angeles: University of California, UCLA Schools of Public Health and Medicine: Roger Detels (Principal Investigator), Otoniel Martínez-Maza (Co-Principal Investigator), Aaron Aronow, Robert Bolan, Elizabeth Breen, Anthony Butch, John Fahey, Beth Jamieson, Eric N. Miller, John Oishi, Harry Vinters, Barbara R. Visscher, Dorothy Wiley, Mallory Witt, Otto Yang, Stephen Young, Zuo Feng Zhang. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, Graduate School of Public Health: Charles R. Rinaldo (Principal Investigator), Lawrence A. Kingsley (Co-Principal Investigator), James T. Becker, Ross D. Cranston, Jeremy J. Martinson, John W. Mellors, Anthony J. Silvestre, Ronald D. Stall. Data Coordinating Center: The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Lisa P. Jacobson (Principal Investigator), Alvaro Munoz (Co-Principal Investigator), Alison, Abraham, Keri Althoff, Christopher Cox, Gypsyanber D’Souza, Stephen J. Gange, Elizabeth Golub, Janet Schollenberger, Eric C. Seaberg, Sol Su. NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Robin E. Huebner; National Cancer Institute: Geraldina Dominguez. UO1-AI-35042, UL1-RR025005, UO1-AI-35043, UO1-AI-35039, UO1-AI-35040, UO1-AI-35041. Website located at http://www.statepi.jhsph.edu/macs/macs.html.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest related to this paper and project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rueda, S., Raboud, J., Plankey, M. et al. Labor Force Participation and Health-Related Quality of Life in HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex with Men: The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. AIDS Behav 16, 2350–2360 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0257-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0257-3