Abstract

Places where people meet new sex partners can be venues for the delivery of individual and environmental interventions that aim to reduce transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI). Using the Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts (PLACE) methodology we identified and characterized venues where people in a southeastern US city with high prevalence of both HIV and STI go to meet new sexual partners. A total of 123 community informants identified 143 public, private and commercial venues where people meet sex partners. Condoms were available at 14% of the venues, although 48% of venue representatives expressed a willingness to host HIV prevention efforts. Interviews with 373 people (229 men, 144 women) socializing at a random sample of 54 venues found high rates of HIV risk behaviors including concurrent sexual partnerships, transactional sex and illicit substance abuse. Risk behaviors were more common among those at certain venue types including those that may be overlooked by public health outreach efforts. The systematic methodology used was successful in locating venues where risky encounters are established and reveal opportunities for targeted HIV prevention and testing programs as well as research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

More people are living with AIDS in the Southern US than in any other region of the country [1]. A substantial proportion of HIV-infected persons in the South live in metropolitan areas and in these small to mid-sized cities municipal and state governments, as well as their community partners, have implemented various HIV prevention initiatives. However, whether these efforts have had an impact on the transmission of the virus HIV remains unclear and available evidence suggests that the behaviors that foster HIV acquisition, including partnership concurrency and underuse of condoms, remain widespread [2, 3].

A recent meta-analysis of 38 randomized trials of individual- and group-level interventions to reduce risk behaviors for acquisition of HIV and among heterosexual African-Americans found such interventions to generally be efficacious [4]. Research also supports an alternative approach that applies community-level interventions directed toward groups that share characteristics and/or a geographic location rather than the targeting of those considered at risk for infection [5–7]. Such interventions include those delivered at venues where risk behaviors actually occur. For example, site-based condom distribution in hotels where commercial sex is available and brothels have been found to be effective [8, 9].

However, for site-level interventions to be most efficacious, identification of the venues where risk behavior is initiated is an essential first step. The selection of such priority venues may be based on perceptions regarding the clientele (e.g., youth, men who have sex with men) and activities at the venue (e.g., alcohol consumption, commercial sex) rather than assessment of the actual behaviors occurring at the site. In addition, less conspicuous venues where sexual and drug-related risk behaviors are initiated may exist but remain unknown to those designing and implementing HIV prevention programs.

Using the Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts (PLACE) method, an HIV/STI intervention-planning tool based on epidemiologic models indicating that new and multiple sexual partnerships are important STI/HIV transmission determinants [10], we aimed to identify and characterize venues where people in a mid-sized North Carolina city with prevalence rates of HIV and other STIs above the state averages meet new sexual partners and measure the prevalence of high-risk sexual behaviors among individuals socializing at these venues. Developed and implemented in sub-Saharan Africa, the PLACE methodology has not been previously applied to identify venues where people meet sexual partners in the US.

Methods

Participants and Study Procedures

We conducted the NC PLACE Study from August through October 2005 using methods we have described in detail previously [10]. Briefly, field work was implemented in three phases. In the first phase, we interviewed community informants aged 18 years or older assumed to be knowledgeable about the area to identify a list of public social venues where people meet new sexual partners in the study city. Informants were those identified by community leaders and included taxi drivers, barbers, police officers, public health officials, clergy, social service providers, among others, and all were asked, “Where do people in this town go to meet new sex partners?” In the second phase, we visited each venue identified by community informants to verify the address of the venue and to interview a representative of the venue who was at least 18 years of age about activities at the site and the potential for on-site HIV/AIDS intervention. Venue representatives were asked about venue characteristics including the potential for sex partners to meet on site and on HIV/AIDS intervention activity. In cases when the venue had no “owner” or “worker,” including venues such as streets, public parks or abandoned lots, the interview was conducted with a person knowledgeable about the venue, such as a nearby resident or a person who frequently socialized at the venue. Although community informants reported both fixed venues and periodic events (e.g., dances, special music events), it was only possible to verify venues. If the venue was closed at first visit, the interviewer returned at least twice to attempt the interview.

In the final phase, we administered a structured face-to-face sexual behavior survey to individuals socializing at a stratified random sample of the verified social venues. To ensure that the selection of venues represented different populations within the study area, the venues were categorized based on venue type prior to randomization. Strata included “Adult bars and clubs,” “Eating establishments,” “Public areas,” “Hotels/Housing,” “Open-air venues” and “Private Homes.” Within each strata of venue type, venues were randomly chosen with a probability proportional to the number of venues in each strata. The number of social interviews attempted per venue was based on venue size. In addition, interviewers attempted to recruit a ratio of two men to one woman, as venue representatives reported men comprised a higher proportion of the venue population than women.

A protocol was developed so that a representative sample of individuals socializing at each venue would be selected. Interviewers were distributed throughout the venue to minimize interviewer discretion in selecting respondents. Selected respondents were brought to a private area to protect confidentiality. After confirming that respondents were at least 18 years old and appeared to the interviewer to be sober, the interviewer obtained verbal informed consent for an anonymous 15–20 min interview. While incentives were not offered, respondents who reported hunger were offered a small snack. Those who asked to be compensated for the interview were provided a small snack or token gift (value of less than $1). Structured interviews included questions regarding respondent characteristics (demographics, current employment status) as well as items related to food security (In the past 30 days, have you been concerned about having enough food for you or your family?), incarceration (In the past 12 months, how many months have you spent in jail/prison?), illicit drug use (Have you used drugs in the past 12 months? Have you used injection drugs, crack, cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, “speed”, or “ecstasy” in the past 12 months?), transactional sex (Have you given or received money, drugs or a place to stay in exchange for sex in the past 4 weeks? 12 months?), sexual partnerships (How many different people have you had sex with in the past 4 weeks? 12 months? How many were new partners in the past 4 weeks? That is, the first time you had sex with the person was in the past 4 weeks), condom use with last new sexual partner (Think about your most recent new partner. The last time you had sex with your most recent new partner, did you use a condom?), sex with a man (for men only) (Some men have sex with other men. By sex we mean either vaginal, anal or oral sex. How many men, if any, have you had sex with in the past 12 months?), prior HIV testing (Have you been [HIV] tested in the past 12 months, tested over 12 months ago, or never tested?) and current symptoms of STI (from list of gender specific symptoms).

The study protocol was approved by the University of North Carolina School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates of each verified venue were obtained. Coordinates were entered into Census 2000 TIGER/Line (US Census Bureau, Geography Division, 2000) and LANDSAT Project (US. Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey) to map the spatial distribution of venues identified as places where people meet new sex partners. Exploratory analysis was performed using ArcGIS Version 9.0 (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, 2004). There were four sites considered to be “super-sites” composed of 6–8 geographically proximal venues. These venues were considered to comprise a part of the same supersite when the venue population socializing moved among these individual venues within the supersite (e.g., a liquor store, an adjacent convenience store, their shared parking lot, and an abandoned lot behind the store could all comprise a super-site).

We calculated frequencies and/or means of socio-demographic, illicit drug use, and behavioral variables using Stata, version 9.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

To assess whether HIV-related drug use and sexual risk behaviors clustered at certain types of venues, we categorized venues into six categories based on their venue type: formal commercial bars/clubs, public community spaces (e.g., restaurants, shops, the library, the hospital), apartment complex public spaces, convenience stores, open-aired sites (e.g., streets, blocks, yards, abandoned lots, parks), the men’s homeless shelter, and private homes converted to bars (liquor houses) or brothels. We then estimated unadjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between the category of the site where the individual was interviewed an HIV-related risk behaviors using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for clustering by the venue where the individual was interviewed [11]. We specified a log link, a Poisson distribution, an exchangeable correlation matrix structure, and a robust variance estimator to correct for overestimation of the error term resulting from use of Poisson regression with binomial data [12–14].

Behavioral variables (see Table 3) were considered dichotomous. Illicit drug use was defined as use of injection drugs, crack, cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, “speed”, or “ecstasy” in the past 12 months. Two dichotomous sexual risk behavior outcomes, including an indicator of high risk partnerships, defined as having at least one new partner or multiple partners (two or more) in the past 4 weeks, and an indicator of transactional sex, defined as having given or received money, drugs or a place to stay in exchange for sex in the past 4 weeks, were also examined.

Results

Venue Characteristics

Community informants (N = 120) reported 143 unique venues where people in their city go to meet new sexual partners. A variety of venue types were listed including traditional venues for socializing, as well as venues not obviously recognized as a meeting venue (Table 1). The most commonly reported venues were restaurants (13%), convenience/food stores (12%), formal commercial bars/nightclubs (11%), abandoned lots or hidden areas (10%), public spaces of apartment complexes (7%), liquor houses (i.e., private homes converted bars that serves liquor) (6%), shops (6%), and streets (6%). The remaining venues represented a diversity of venue types and included a recovery house and the men’s shelter, public areas such as movie theatres and roller rinks, parks, and places of worship. Of the venues reported by community informants, greater than 27% were located outdoors (abandoned areas, public spaces of apartment complexes, streets, parks, taxi stands). Twenty of the 143 reported venues were either closed or could not be located. The remaining 123 (86%) venues were mapped and visited and site representatives at 98 (80%) agreed to participate. A comparison of these venues with the 25 where site representatives declined to be interviewed found the types of venues to be similar in each group. Formal and informal bars, restaurants, and apartments were the most commonly reported sites among the sites that did and did not participate. However, the two movie theaters reported as sites where people meet sexual partners both declined to participate.

Risk Behaviors Reported by the Site Representatives

Half (54%) of site representatives reported that the venue was a place where people meet new sex partners. According to representatives, sex occurred on site at 17% of the venues and 17% reported that sex workers solicited customers at the venue. A large majority of the representatives of the venues named by community informants (79%) reported that students or youth under the age of 18 years of age socialize at the venue. Injection drug users were reported to frequent the venue according to 32% of site representatives.

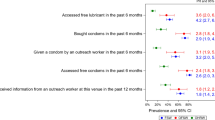

Of the venues visited, 37% had previously hosted an HIV prevention effort such as educational talk on HIV/AIDS, peer health education programs, condom promotion, HIV/AIDS video viewings, HIV/AIDS radio program broadcast, HIV/AIDS posters or leaflets, or on-site HIV testing. At 14%, condoms were available and on display but at 80% condoms had not been available on site during the previous year. Site representatives at 48% of the venues indicated a willingness to participate in an HIV prevention effort in the future.

Characteristics of Persons Socializing at the Venues

Demographics

Of the 98 venues visited, 54 were randomly selected for interviewing of those socializing at the venue. Four of these venues were “super-sites” composed of 6–8 geographically distinct but proximal or contiguous venues. Since the venue population generally moves frequently between the venues within a super-site, it is difficult disaggregate venues within the super-site for the purpose of sampling. At five of the 54 venues no interviews were completed as there were very few individuals socializing and those approached for the interview refused to participate. At more than half of venues (27 venues) fewer than 5 individuals were interviewed, and at the remaining venues (22 venues), greater than five individuals were interviewed (range: 5–38 individuals).

A total of 373 individuals recruited while socializing on-site agreed to participate (75% participation rate), with no difference in participation rate by gender (women 78%; men 74%). The demographic characteristics of these respondents are detailed in Table 2. The mean age of the sample was 32 years. Approximately two-thirds of the sample was African American and 61% were male. Of the men, only about 10% reported sex with a man in the past 12 months. More than 90% of respondents resided in the study city. Of the men, 45% visited the venue daily as did 38% of the women. Approximately one-third of men and one-quarter of women had not completed high school and unemployment was reported by more than one-third of men and women. Recent worry about food security was not uncommon among men (18%) and women (21%). High rates of incarceration for greater than 24 h were reported by men and women; one in five of the men had been imprisoned within the prior 12 months. Just under 20% of both men and women had an intimate partner who was themselves incarcerated within the prior 12 months.

Illicit Drug Use

Use of any illicit drug during the prior 12 months was reported by one-third of men and one-fifth of women. Crack/cocaine was most commonly used (Table 2). Reported injection drug use (IDU) was rare (<6%).

HIV/STI Risk and Testing Behaviors

Most of the respondents had at least one new sex partner or multiple partners in the past 4 weeks (57% of men and 44% of women) (Table 2). Of those who reported at least one new partner in the past 12 months, 14% of men and 25% of women reported not having used a condom with their most recent new sex partner. In addition, 15% of men and 17% of women gave or received money for sex during the prior 4 weeks.

Approximately 15% of women and 8% of men reported symptoms suggestive of an STI in the past 3 months, including pain on urination (men), discharge from the penis (men), unusual vaginal discharge (women), lower abdominal pain (women), and/or genital ulcers (men and women). Half of men and 59% of women underwent HIV testing in the prior 12 months, and an additional 21% of men and 15% of women were tested more than 1 year ago.

Risk Behavior of Socializing Individuals and Venue Type

The risk behaviors reported by individuals socializing at the venues studied are detailed in Table 3. Compared with individuals interviewed at formal commercial bars/nightclubs, of whom 18% reported illicit drug use in the past 12 months, illicit drug use was much higher among individuals interviewed at the men’s homeless shelter (77%; PR: 4.40, 95% CI 2.45–7.89), private homes converted to bars/brothels (55%; PR: 3.14, 95% CI 1.65–5.99), and convenience stores (52%; PR: 2.99, 95% CI 1.60–5.59) and also appeared to be higher at open aired venues including streets, parks, and public spaces in apartment complexes. More than half of the respondents reported having at least one new sex partner or two or more sex partners during the past 4 weeks, however, prevalence rates were not significantly different between venue types. Although, those interviewed at the Men’s Shelter tended to be more likely to have new/multiple partnerships compared to other venue types (PR: 1.21, 95% CI 1.00–1.46) but the number of respondents at this site was small (n = 13). While 4% of individuals interviewed at formal commercial bars/nightclubs reported having given or received money, food, or services for sex in the past 4 weeks, recent transactional sex was markedly higher among respondents at the men’s homeless shelter (62%; PR: 14.5, 95% CI 7.3–28.9) and private homes converted to bars and brothels (40%; PR: 9.4, 95% CI 4.3–20.6) and was approximately 4–5 times higher at convenience stores and the open aired venues.

Those socializing at the venue were more likely to report sex partners meet at the site than were site representatives interviewed at the same venue. Across all the venues, socializing individuals reported relatively high rates of HIV/STI risk behaviors with no major differences seen between those interviewed at venues acknowledged or not acknowledged by representatives to be where new partners meet. For example, the majority of respondents reported a recent high-risk partnership—having at least one new partner or multiple sex partners in the past 4 weeks—regardless of whether they were interviewed at venues whose managers affirmed that people meet new sex partners at their sites (56%) or at venues whose managers denied such on-site meeting (51%; P = 0.432). Likewise, trading sex for money, goods, or services was common at venues where representatives affirmed that people meet partners on site (17%) and at venues where representatives reported no people meet sex partners (19%; P = 0.613). Therefore, reports of venue managers did not provide accurate information about whether their venue was a potential priority venue for STI/HIV prevention.

Discussion

The PLACE methodology was able to successfully identify a diverse collection of venues in a US city where persons socialize and meet new potential sex partners. These venues included locations where the establishment of new partnerships was expected (e.g., formal bars) but also those that were less obvious as places where new sexual partners established (e.g., convenience stores, homeless shelter, open aired spaces). Indeed, most any type of locale in the study city where people congregate including churches, athletic events and even clinics were reported as venues where new partners are sought and found.

Behaviors that heighten risk for acquisition of HIV as well as other STIs were commonly reported by participants, including illicit drug use, multiple sexual partnerships and the trading of sex. Previously, we have reported that for men and women socializing at these venues a personal history of incarceration and incarceration of a recent sexual partner were associated with sexual risk behaviors [15]. In this analysis we found that certain venues appear to attracted individuals with risky behaviors. Not surprisingly, among those at private homes used as brothels and bars risk behaviors were common; however, the finding of relatively high rates of risk behaviors among those socializing at convenience stores, open aired spaces and apartment complex public spaces was less anticipated. Men at the homeless shelter had some of the greatest self-reported behavioral risks and this may reflect their incarceration history as well as other factors such as substance use and mental health disorders. In contrast, considerably less risk behavior was reported by patrons of formal bars and clubs, venues that are often the focus of HIV prevention outreach efforts.

Importantly, as was the case with previous application of the methodology to identify venues in sub-Saharan Africa, PLACE was readily accepted by the community partners who helped direct the initial stages of the study, as well as site representatives and those socializing at the site. Refusal rates for interviews among those at the venue were relatively low (25%), although higher than recorded in our prior application of PLACE in Jamaica (13%), South Africa (2%), and Madagascar (<1%) [10, 16, 17]. Interviews with those socializing at the venues were able to be successfully conducted despite the challenge of quickly questioning participants about personal behaviors in a social setting.

The potential value of the PLACE method in identifying venues where new partnerships are initiated is highlighted by the number of venues that reported a willingness to host HIV/STI prevention initiatives. Most venues, despite the behaviors of those socializing there, had little or no HIV/STI prevention activities available. With their identification, these venues can be considered for future community-based prevention initiatives. Such initiatives can include not only distribution of condoms and educational messages but also HIV testing and can be adapted, with community guidance, to be delivered at a variety of venue types. For example, at convenience stores frequented by persons engaged in sex work, free condoms and HIV testing can be made available. With calls to expand HIV/STI testing in order to identify and treat those discovered to be HIV-infected [18]—so called, seek-test-and-treat—the PLACE method can be envisioned as an important element in the identification of those who are at greatest risk and, therefore, should be targeted for testing.

There are several study limitations. Foremost, the identification of venues was limited by the reports of community informants. While a diverse group of community informants was identified via discussions with persons knowledgeable about the community and the many of the venues listed were reported by more than one informant, there may be additional venues of interest that were not reported or remain unknown by the informants. In addition, risk behaviors were self-reported and the reported use of condoms with the last new partner was high (>70% for both men and women) and much greater than that reported from the National Survey of Family Growth (<30%) conducted among more than 12,000 persons age 15–44 years old across the US [19]. The higher than expected rate of condom use may reflect social desirability bias among those interviewed face-to-face compared to the computer assisted questioning conducted during the national survey [20, 21]. Alternatively, the respondents interviewed may have had significant exposure to HIV/STI prevention messages, such as during incarceration, and therefore used condoms even while practicing risky behaviors. Respondents also had high rates of prior HIV testing, consistent with rates among those with higher HIV risk in the national survey, suggesting an appreciation of risk among those interviewed. A surprising finding was the high proportion of the listed venues that were where young people and students socialize. However, due to ethical considerations regarding informed consent, minors under 18 years of age were not interviewed, a limitation of this study. Future study of minors socializing at such venues is warranted given their frequent presence at these venues.

In conclusion, we found the PLACE methodology, a venue-based approach for the delivery of HIV prevention services, originally developed and implemented in sub-Saharan Africa, to be rapid, feasible and well-accepted when applied in a US city. PLACE can be a valuable initial step in a strategy that aims to locate diverse social venues where community-based interventions to promote condom use, HIV education and HIV testing can be implemented.

References

CDC. HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2007, vol. 19. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2009. p. 1–63.

Adimora A, Schoenbach V, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent partnerships among rural African Americans with recently reported heterosexually transmitted HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:423–9.

Farley TA. Sexually transmitted diseases in the Southeastern United States: location, race, and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7 Suppl):S58.

Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–94.

Sikkema KJ, Anderson ES, Kelly JA, et al. Outcomes of a randomized controlled community-level HIV prevention intervention for adolescents in low-income housing developments. AIDS. 2005;19:1509–16.

Sikkema KJ, Kelly JA, Winett RA, et al. Outcomes of a randomized community-level HIV prevention intervention for women living in 18 low-income housing developments. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:57–63.

Ross MW, Chatterjee NS, Leonard L. A community level syphilis prevention programme: outcome data from a controlled trial. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:100–4.

Egger M, Pauw J, Lopatatzidis A, Medrano D, Paccaud F, Smith GD. Promotion of condom use in a high-risk setting in Nicaragua: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355:2101–5.

Rojanapithayakorn W. The 100% condom use programme in Asia. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14:41–52.

Weir SS, Pailman C, Mahlalela X, Coetzee N, Meidany F, Boerma JT. People to places: focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS. 2003;17:895–903.

Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30.

Zocchetti C, Consonni D, Bertazzi PA. Estimation of prevalence rate ratios from cross-sectional data. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:1064–5.

McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:940–3.

Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6.

Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, et al. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. J Urban Health. 2008;85(1):100–13.

Weir SS, Figueroa JP, Byfield L, Hall A, Cummings S, Suchindran C. Randomized controlled trial to investigate impact of site-based safer sex programmes in Kingston, Jamaica: trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(6):801–13.

Khan MR, Rasolofomanana JR, McClamroch KJ, et al. High-risk sexual behavior at social venues in Madagascar. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(8):738–45.

Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2380–2.

Anderson JE, Mosher WD, Chandra A. Measuring HIV risk in the U.S. population aged 15–44: results from Cycle 6 of the National Survey of Family Growth. Adv Data. 2006;23(377):1–27.

Catania JA, Gibson DR, Chitwood DD, Coates TJ. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:339–62.

Geary CW, Tchupo JP, Johnson L, Cheta C, Nyama T. Respondent perspectives on self-report measures of condom use. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:499–515.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sherri Harris, Willie Garrison, Nancy Jackson, and Anthony Anderson for their leadership in the field and insights into study findings; the NC PLACE Steering Committee members for guidance and support through the study planning, implementation, and dissemination; the NC PLACE Study interviewing team members for their diligence; and members of the University of North Carolina Bridges to Good Health and Treatment (BRIGHT) Working Group for their consistent support during NC PLACE field and data analysis activities, with particular thanks to Monique Williams, Tracina Williams, Danielle Haley, Becky Stephenson-White, Anna Scheyette, Carol Golin, and Andrew Kaplan. This study was supported by a grant from the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (9P30A150410) and the National Institute of Mental Health, NIH (R01 MH068719-01). The conclusions expressed here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We dedicate this research to the memories of Andrew Kaplan and Willie Garrison, who continue to inspire our efforts to prevent HIV transmission in North Carolina and beyond.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wohl, D.A., Khan, M.R., Tisdale, C. et al. Locating the Places People Meet New Sexual Partners in a Southern US City to Inform HIV/STI Prevention and Testing Efforts. AIDS Behav 15, 283–291 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9746-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9746-4