Abstract

Certain constructs are demonstrated in the research literature to be related to HIV risk behaviors among African American adolescents. This study examines how well these constructs are addressed in evidence-based interventions (EBIs) developed for this population. A literature review on variables for sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescents was undertaken. Simultaneously, a review was conducted of the contents of HIV-prevention EBIs. To facilitate comparison, findings from both were organized into constructs from prominent behavior change theories. Analysis showed that environmental conditions and perceived norms were frequently associated with sexual risk behaviors in the literature, while EBIs devoted considerable time to knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy. Findings imply that (a) EBIs might be complemented with activities that focus on important constructs identified in the literature and (b) researchers should better assess the relationship between skill development and HIV risk behaviors. Implications for practice and research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Compared with the total U.S. adolescent population, African American adolescents are at increased risk for negative health, academic, and social outcomes due to consequences of risky sexual behaviors. Over 65% of African American high school students report having had sexual intercourse, 15% had sexual intercourse before the age of 13, 29% had sexual intercourse with more than 4 persons, and 38% did not use a condom at last intercourse [1]. Risky sexual behaviors, such as these, increase the risk for HIV infection, sexually transmitted diseases (STD), and pregnancy [2–4], and have been associated with lower levels of academic achievement, increased high school drop-out rates, and poor social outcomes [5, 6].

In 2007, in the 34 states with long-term confidential name-based HIV reporting, 72% of HIV/AIDS diagnoses among 13–19-year-olds were among African Americans, yet African Americans accounted for only 17% of the general population in this same age range [7]. A CDC study estimates that nearly one in two (48%) African American girls aged 14–19 in the United States is infected with at least one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases (human papillomavirus [HPV], chlamydia, herpes simplex virus, or trichomoniasis) [8]. In 2006, birth rates for African American adolescents ages 15–19 were 63.7 per 1,000 [4]. The impact of HIV, STD, and teen pregnancy on African American youth is distressing.

Adolescence is a critical time to promote healthy sexual behaviors; healthy behaviors established during adolescence are more likely to be sustained through adulthood. Culturally relevant interventions to reduce risky sexual behaviors remain one promising approach to reducing these impacts for African American youth. Multiple reviews have demonstrated that behavioral interventions shown to be most efficacious are culturally tailored and preceded by formative ethnographic research to inform intervention development. Successful behavioral interventions shown to reduce HIV risk behaviors typically focus narrowly on specific behaviors relevant to the target population, include clear messages about situations leading to risk behaviors, and describe methods to prevent these situations [9, 10].

Several behavioral interventions developed specifically for use with African American youth to prevent HIV infection have been designated by CDC as efficacious, based on the outcomes of rigorously designed trials [11], and most of these interventions have been packaged by CDC. That is, the research protocols from efficacious HIV behavioral interventions were translated into packages of user-friendly materials for use by HIV prevention providers, including health departments, schools, and community-based organizations [12]. We believe that the development, packaging, and diffusion of multiple, evidence-based, culturally relevant behavioral HIV prevention interventions has been an important advance in fighting the HIV epidemic among African American adolescents, however there remains room for further advancements. To enhance their impact on the epidemic, it might be possible to modify and complement EBIs addressing HIV prevention, such that their outcomes are increased and sustained.

In 1991, at a meeting commissioned by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), leading theorists of influential behavior change models suggested one approach to enhancing behavioral interventions. They advised, “given the limited resources available for prevention and change programs, it is essential that interventions focus upon changing those constructs that have the greatest probability of influencing the likelihood that members of a given population will engage in the behavior in question” [13]. In this report, we will focus on assessing EBIs against a theoretical framework and research on behavioral change, to identify potential areas for improvement.

Our objectives are twofold: (a) to describe behavior change theoretical constructs most likely to influence the extent to which African American adolescents will engage in health-promoting behaviors for HIV prevention; and (b) to identify the degree to which these constructs are reflected in current EBIs. Determining gaps in the EBIs could suggest mechanisms to improve their efficacy.

Methods

We used a three-step process to assess gaps in the theoretical constructs represented in current EBIs: (a) comprehensive review of the literature on variables associated with sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescents; (b) analysis of the content of HIV-prevention EBIs that were developed for, and have been used with, African American youth; and (c) categorization of the findings into the most prominent behavioral-change theory constructs. The constructs of the behavioral-change theories were used to compare the literature findings and the contents of the EBIs.

Study Identification

Literature searches were performed in four public research databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO using the following search terms: HIV, AIDS, STD, teen pregnancy, sexual risk behavior, risk taking behavior, risk behavior, sexual behavior, protective behavior, protective factors, adolescent, adolescent behavior, black, African American, and urban. Additional studies were found through manual journal searches and reference lists in retrieved articles. Our criteria for inclusion were studies that were: (a) conducted in the United States, (b) published in peer-reviewed journals from 1995 through 2007, (c) included multivariate analyses, and (d) had sufficiently large sample sizes (at least 100 for significant results). Additionally, study participants had to be younger than 19 years, and the majority of the sample (>50%) had to be African American.

Eight hundred ninety-six (896) abstracts were initially identified and examined for relevance and 106 articles that had the potential to be included were identified and obtained for detailed review. Of these 106 articles, 52 did not meet our inclusion criteria. Those that focused on subpopulations, such as detained or pregnant adolescents, and follow-up surveys of intervention evaluations were not included. Fifty-four studies met our inclusion criteria, most of these studies (83%) were cross-sectional, with a few using baseline data from longitudinal studies. Forty-three articles used samples that were 100% African American, and only 4 studies had samples that were between 51% and 78% African American.

The 54 studies that met our criteria for inclusion were systematically reviewed to identify variables related to five sexual risk behavior outcomes: ever had sex, age of first sex, number of sexual partners, unprotected sexual intercourse (did not use a condom), and history of STD. Due to the low number of studies that separated ever had sex into specific type of sex (oral, anal, vaginal), this variable was looked at comprehensively. Each study was reviewed and coded for sample characteristics, study design, and variables found to be significantly related to one or more of the five sexual risk behavior outcomes of interest. Only findings resulting in statistical tests of hypotheses assessing relationships between the theoretical constructs and sexual risk behavior outcomes were extracted for analysis. A single study could, thus, contribute multiple findings to the review.

Identification of Evidence-Based Interventions

To identify EBIs for this review, interventions were assessed and had to meet three inclusion criteria: (a) met criteria for CDC’s Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) project as an evidence-based intervention [11], (b) have been packaged, or were in the process of being packaged, into user-friendly materials for use by HIV prevention providers, and (c) the original research sample included >50% African American youth. The PRS project identifies evidence-based, behavioral interventions for individual or group applications—but not school-based programs—that have demonstrated efficacy in reducing HIV/STD incidence, decreasing HIV-related risk behaviors, or in promoting safer sexual behavior (e.g., being abstinent, using condoms) [11, 14–17].

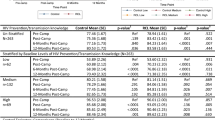

A total of seven EBIs were identified (Table 1). Five packaged programs were identified as evidence-based by PRS (Becoming a Responsible Teen [BART] [18], Be Proud! Be Responsible! [Be Proud] [19], Focus on Youth with Informed Parents and Children Together [FOY with ImPACT, previously named Focus on Kids] [20, 21], Sistas, Informing, Healing, Living and Empowering [SiHLE] [22], and Street Smart [23]). In addition to these five, two additional packaged school-based programs (Making a Difference, and Making Proud Choices [24]) not included in the PRS review (which does not assess school-based interventions) met the evidence-based criteria set by PRS and were included in this review. Six of the seven interventions were specifically developed to be culturally relevant for African American youth and 100% of research participants were African American. Street Smart was the exception with 53% of the sample African American. One additional intervention, Project Adult Identity Mentoring (AIM) [25], met all inclusion criteria but was a youth development intervention based on the Theory of Possible Selves [26], and not a traditional HIV prevention program based on behavioral theory. Because the theoretical framework used for this review differed significantly from the Theory of Possible Selves, we did not include AIM in our overall analysis. Table 1 describes the theoretical background, and the number and length of sessions in each intervention.

Theoretical Framework

To classify the content of the EBIs and the significantly associated variables found in research, we used an organizing framework based on constructs from widely-used theories. This framework provides a structure and context for examining the content, and facilitates comparisons of activities of the EBIs and the published literature on African American adolescent sexual risk behaviors and the outcomes. The classification of individual activities from the EBIs and literature content into theoretical constructs assists in identifying gaps and areas for improvement of the EBIs. For example, if research has found the environmental conditions to be influential, yet little of the content in an EBI focuses on environmental conditions, this may be an area to strengthen in the intervention.

For this review, we applied a set of eight constructs common across multiple widely-used theories, which were identified at the Theorists’ Workshop. The theories include the following: Health Belief Model, Social Cognitive Learning Theory, Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Self Regulation and Self Control, Theory of Subjective Culture, and Theory of Interpersonal Relations [13]. The Theorists’ Workshop identified eight common constructs of any given behavior: strong intentions to perform a behavior; environmental constraints—relabeled environmental conditions—that foster feasible social, ecological, and structural influences to perform a behavior; having the skills necessary to perform the behavior; a positive attitude towards the behavior; perceived norms about the behavior that are more positive than negative; consistency between an individual’s personal standards or values and practicing the behavior; positive emotional reaction towards performing the behavior; and self-efficacy, the individual’s belief that he or she can complete the behavior.

The theorists concluded that while all eight constructs influence behavior, their impact and importance vary. They also identified constructs that are necessary to produce a behavior and that influence the strength and direction of the behavior. Three of the constructs, environmental conditions, intentions, and skills, were viewed as necessary and sufficient for producing healthy behaviors. The remaining five constructs, positive attitude, perceived norms, consistency, positive emotional reaction, and self-efficacy, were viewed as influencing the strength of intention. Therefore, the theorists concluded that interventions should address all three of the necessary constructs and focus on the one or two constructs from the remaining five most likely to influence participants to engage in the desired behavior.

Two additional constructs, other related risky behaviors and knowledge, not included in the original theoretical framework, were also assessed. Other related risky behaviors (e.g., substance use, delinquent behavior, dating violence, lower school performance) have been shown in the research literature to co-occur with the sexual risk behavior outcomes [27–35], although only limited research addresses the direction and causation of their relationships. While other related risky behaviors are not a theoretical construct, we did include them in our analysis because they share common associations to sexual risk behaviors, and if we intervene on those behaviors, we may also have an impact on sexual risk behaviors.

In addition, knowledge (e.g., factual information about HIV transmission and prevention) was not included in the theorists’ framework. This omission may be due to the well-established finding that knowledge is an important precursor to the other constructs. However, while knowledge may provide a foundation, greater knowledge may not assure responsible behavior. Thus, while knowledge provides a foundation for human action, knowledge alone is not sufficient to change behavior. This finding was established in the literature prior to the 1991 NIMH meeting. However, due to the prominence of knowledge in the EBI’s we felt it was important to include it in our analysis.

To summarize, for this review we assessed a total of ten constructs, eight constructs (intentions, environmental conditions, skills, positive attitude, perceived norms, consistency, positive emotional reaction, and self-efficacy) identified from the Theorists Workshop and two additional constructs (other related risky behaviors and knowledge) that were identified as important constructs in this and previous literature reviews.

Application of Theoretical Framework

From the variables (see Table 2) found in the literature, we grouped those that were significantly associated with the five sexual risk behavior outcomes according to the theoretical constructs noted above. The authors, social scientists with experience in behavior change theory and the content of HIV prevention interventions, undertook a three-step process. First, the 54 articles that met the inclusion criteria were divided equally amongst the authors to examine and sort the variables by theoretical construct. Classifications were then shared, and inconsistencies were resolved through group discussion. Consensus was reached for all articles. For consistency, other reviews that classified similar variables were consulted [36, 37].

A similar approach was used to review the content of each EBI to determine which of the ten theoretical constructs were addressed by the intervention activities. The same team undertook a three-step process. First, each of the seven interventions was examined by two reviewers to determine which activities within each session operationalized (i.e., measurement of concepts) specific theoretical constructs. Classification of activities to constructs was then shared, and inconsistencies resolved. Consensus was reached for all EBIs. On decision-rule charts the team developed for decision-making, we grouped similar activities to ensure consistency of classification across interventions.

For each EBI, a dose score was calculated. The authors critically considered the best approach for calculating a dose score. One approach is to sum the total number of minutes in which each theoretical construct was addressed. Another possibility is to add up the number of activities that addressed the construct. The authors decided to use the total number of minutes rationalizing that this approach was more representative of both time and number of activities. A dose score was calculated for each construct by summing the number of minutes allotted for activities that operationalized each construct. Due to the difficulty of determining exactly how many minutes were devoted to each construct within the activity, we included the full number of minutes for the activity, regardless of how long the activity focused on the particular construct.

Activities could operationalize more than one theoretical construct, so we counted the activity minutes for all constructs the activity addressed. For example, several EBIs included activities in which participants were asked to identify behaviors that do or do not put youth at risk for HIV infection. These activities used multiple methods (i.e., games, role-plays, quizzes) and were coded as seeking to influence knowledge, positive attitude, and consistency. The full number of minutes (e.g., 15 min) designated for the activity was included in the dose sum for each of these constructs. An important caveat is that for perceived norms only the activities that addressed perceived norms specifically were included in the dose. However, often the rationale for intervening at the group level is to influence perceived norms positively. It is posited that groups of peers who go through a program together can facilitate perceived norms supporting healthy behaviors [38]. Therefore, it is possible that the dose for perceived norms is underestimated.

Results

Associated Variables

Table 2 presents the variables significantly associated with the five sexual risk behavior outcomes in the review, grouped by theoretical construct. The theoretical constructs having the greatest evidence, based on the literature review, of influence on HIV risk behaviors were environmental conditions and perceived norms. Specifically, under environmental conditions, variables associated with an increase in all five of the sexual risk behaviors of interest included sexual possibility situations (e.g., time alone with a member of the opposite sex) [39–42], media influences [43, 44], and a variety of societal and cultural factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, neighborhood disorganization) [45–51]. Environmental conditions that were associated with a decreased risk of all five of the sexual risk behaviors of interest included parental connectedness (e.g., emotional closeness) [46, 52–59]; family structure [45, 47, 50, 54, 57, 60, 61], parental involvement [47, 49, 58, 62]; parent–adolescent communication about sex, condoms, or birth control [55, 62–68]; and adolescent perceptions that parents were monitoring their behavior [42, 62, 64, 69–74].

Under the category of perceived norms, several variables were found to be associated with all of the sexual risk behaviors of interest. Among these were perceptions of peer sexual behaviors [40, 50, 64, 65, 75–81] and perceptions of related peer behaviors, such as delinquent behavior [46, 50, 58] and friends’ drug, alcohol, or tobacco use [46, 58, 73, 77]. Also under perceived norms, positive peer support [46] and family norms [49, 55, 79] were found to be protective for four of the sexual risk behavior outcomes: decreased ever had sex, later age at first sex, fewer number of sexual partners, and less unprotected sexual intercourse.

The relationships between sexual risk behavior and the theoretical constructs of intention and skills had the fewest number of studies demonstrating associations. However, the intention to have sex (e.g., sexual willingness) was associated with ever had sex [77, 78]. Studies that explored the association between skills and sexual risk behaviors found that skills related to decision-making [60], communication with a sex partner [66, 80, 82], and communication with friends about sex [64, 67] were all protective against ever had sex, age at first sex, and unprotected sexual intercourse.

Finally, under the category other related risky behaviors, variables associated with an increase in all five of the sexual risk behaviors of interest included substance use [58, 61, 75, 77, 79] and delinquency [46, 48, 58, 73, 83]. Higher school performance was found to be protective for ever had sex [61] and lower school performance was associated with four of the sexual risk behavior outcomes: increased ever had sex, earlier age of first sex, less unprotected sex, and fewer sexual partners [46, 49, 54, 58, 61, 79]. Dating violence was associated with higher incidence of STD and more unprotected sexual intercourse [84]. Knowledge was not measured by any of the studies included in our review.

Evidence-Based Interventions

All seven of the EBIs had activities that operationalized all ten theoretical constructs. Across the interventions (Table 3), knowledge had the largest dose, with a mean dose of 314 min (SD = 119). Knowledge activities included those that identified a variety of behaviors and levels of risk for HIV infection, provided information about condom use and other contraception, and discussed how HIV was transmitted. Six of the seven interventions provided both HIV and general sexual health knowledge. Be Proud provided only HIV-specific knowledge.

The next two constructs with large doses across the EBIs were self-efficacy (M = 276; SD = 131) and the related construct of skills (M = 248; SD = 113). Activities focused on self-efficacy for abstinence, safer sex, or communication. Role-plays, condom demonstrations, and condom hunts were common activities for operationalizing these constructs. All seven interventions addressed self-efficacy for communication, including verbal, non-verbal, and communication styles. Three of the interventions (FOY with ImPACT, SiHLE, and Be Proud) had activities that addressed self-efficacy for both condom use and abstinence. Making a Difference focused on self-efficacy for abstinence, while BART, Making Proud Choices, and Street Smart included activities on self-efficacy for condom use. Skills activities included those designed to teach condom use, decision-making, communication, and refusal or negotiation skills. Many of these activities were the same activities that operationalized self-efficacy. All interventions, except for Making a Difference, addressed all five skills. Making a Difference is an abstinence-based intervention that does not include activities to build skills in condom use.

Across the seven interventions, consistency had a mean dose of 219 min (SD = 92). SiHLE had the largest consistency dose (379 min). All seven interventions addressed the consistency construct and included activities to encourage pride and work on improving their community. Community connectedness was addressed in two of the EBIs (FOY with ImPACT and SiHLE), and included activities about ethnic pride and involvement in school, church, and community. Future aspirations were addressed by five interventions and included goal-setting activities. Perceived risk for HIV infection was addressed by all interventions and included HIV-positive speakers and epidemiological HIV data specific to the African American community. Beliefs and values were also addressed by all interventions and included values clarification and how values impact decision-making.

Across EBIs, the theoretical construct positive attitude had a mean dose of 199 min (SD = 82); activities primarily focused on the consequences of decisions and behaviors. A somewhat similar construct, positive emotional reaction, had a smaller mean dose (M = 89; SD = 63). Emotional reaction was often a small piece of an activity and rarely a major emphasis.

All interventions focused on perceived norms (M = 72; SD = 46). Three interventions addressed norms regarding related peer behaviors, such as substance use, date rape, or drug trafficking (FOY with ImPACT, Making a Difference, and SiHLE). Perceived norms activities included reconciling the perceived estimate of peers engaging in risk behaviors with the actual number of youth engaging in those behaviors and addressing peer pressure. FOY with ImPACT was the only intervention to focus on family norms; its activities included parent–child discussions about family values.

Compared with the other constructs, environmental conditions (M = 61; SD = 78) had a low dose with the exception of FOY with ImPACT, which included a component for parents. All interventions included activities to encourage reduction of sexual possibility situations. Minimal time was spent addressing participants’ intentions to have sex (M = 25; SD = 19).

All seven of the interventions addressed other related risky behaviors (M = 116; SD = 125). Three (FOY with ImPACT, SiHLE, and Street Smart) addressed dating violence and all seven interventions addressed peer behavior of substance use. Focus on Youth with ImPACT also addressed delinquency and school performance.

Discussion

While all seven of the EBIs addressed the ten identified constructs, this review suggests that the specific variables shown to have stronger associations with sexual risk behavior among African American adolescents may not be given adequate emphasis in the interventions for long term behavior change. This knowledge may help improve and strengthen future interventions. Certain constructs might be more important for particular behaviors and populations, and should therefore be a more prominent focus of prevention interventions.

For example, the constructs of environmental conditions and perceived norms have been found frequently to be significantly associated with sexual behaviors among African American adolescents. This finding reinforces the Theorists’ Workshop conclusions, where environmental conditions was one of the three constructs, along with skills and intentions, noted as being necessary and sufficient to produce behavior change. It also reinforces the importance of community and family in the African American culture [85, 86]. A likely explanation and hypothesis that needs further exploration might be that because the EBIs emphasize individual behavior change, little time or content is devoted to environmental conditions and perceived norms.

Another explanation for the limited number of activities addressing perceived norms is due to the belief that the dynamics of a group intervention sufficiently addresses perceived norms. However, it may strengthen intervention impact if there was an increase in activities that directly address perceived norms. Environmental conditions such as parental monitoring, communication, and connectedness, as well as perceived norms such as those related to peer sexual and other related risky behaviors, were shown in the literature to frequently be associated with sexual risk behavior outcomes. Adding activities that incorporate parent involvement (as done in FOY with ImPACT) or address perceived norms might enhance and sustain the impact of EBIs [21].

To complement EBIs and potentially increase their effectiveness, broader environmental constructs might best be addressed through programs that reach youth in multiple places where they live and pursue their activities, or programs that target important adults in their lives. Examples of such approaches could include parent education programs [21]; family strengthening interventions [87]; service learning [88]; career planning [89]; and increasing access to STD and HIV testing, care, and treatment [90–92]. Many of the variables that made up the construct of environmental conditions are associated with poverty (e.g., family structure, neighborhood disorganization, unemployed parents) [93]. Therefore, structural interventions that address the causes of poverty may be another promising approach to reduce HIV among African American youth. One such approach that can address the impact of poverty is positive youth development, which provides youth with an atmosphere of hope, encourages supportive and nurturing relationships among youth and adults, and offers opportunities for youth to nurture their interests and talents, practice new skills, and gain a sense of personal or group recognition.

Similarly, the research appeared to be missing components found in the EBIs. Knowledge had the largest dose in the EBIs out of all of the constructs; however, knowledge did not emerge in the literature review. Knowledge is well accepted as a necessary but insufficient factor for modifying behavior [94]. As a result, most research now focuses on constructs that assume pre-existing knowledge or incorporate foundational knowledge into the other constructs studied, suggesting that greater knowledge might improve attitudes, perceptions of perceived norms or skills, and these mediating factors in turn might affect behavior, but the statistical analyses may not always capture this indirect impact of knowledge on behavior. Alternatively, it could be that knowledge is already high among African American youth, and more time could be better spent addressing other theoretical constructs such as environmental conditions or perceived norms. One approach to determine the optimal level of knowledge for behavior change would be to include a baseline assessment of knowledge at the beginning of the intervention. Depending on the level of knowledge at baseline, the knowledge dose could be increased or decreased.

Another area that seemed to be underdeveloped in the research literature was skills. As noted above, skills are viewed as one of three factors that are necessary and sufficient to create behavior change. Skills-building is frequently identified as a critical component of effective HIV prevention programs for young people [95], yet our review found only a small number of studies that measured the association between skills and sexual risk behaviors.

All seven EBIs found to be effective for African American youth have skills-building as a significant element; yet, in the literature, only communication and decision-making skills have been found to be associated with protective behaviors. This omission could be attributable to a lack of studies measuring these skills, insufficient measurement tools, or a lack of significant associations between skills and our outcome measures. In our review of the literature on African American adolescents, including the significant and non-significant associations, we found that skills measurement was underrepresented. This finding was also noted by Buhi and Goodson [36] in a comparable review of the general adolescent literature. Further, the Theorists’ Workshop called for the development of guidelines to serve as the basis for developing skills measures. While several studies have attempted to measure the effect of teaching condom skills on subsequent condom use [22, 96, 97], this area is still underrepresented in the literature. More research is needed to better understand the relationship between skills and sexual risk behavior outcomes of African American youth.

Results for perceived risk of HIV infection were inconsistent in the literature; both lower and higher perceived risk were associated with increased sexual risk behaviors. Perhaps those who perceive their risk to be low feel invulnerable to HIV/STD; and those who perceive their risk to be high are accurately reflecting lower self-efficacy for safer sex or communication, and are less able to negotiate sexual risk reduction behaviors. Although all seven of the EBIs addressed perceived risk for HIV infection, more research is needed to understand the mechanism of how perceived risk is associated with sexual risk behavior.

The importance of basing prevention interventions on theory has been demonstrated in the research literature [9] and has been reinforced by this review, yet it is also important to recognize that there may be important constructs that traditional behavioral change theories do not address. Prevention interventions that use strengths-based conceptual frameworks can provide the motivation and confidence needed to use the skills taught in HIV prevention interventions [98] by helping youth strengthen relationships, giving access to positive networks of supportive adults, and developing a more positive view of their future by providing academic, economic and volunteer opportunities. For example, the efficacious intervention, AIM [25] is not a traditional HIV prevention program and is based on the Theory of Possible Selves [26] that focuses on developing youth’s aspirations for the future. The program was able to significantly change HIV risk behaviors.

Although individual theories have dominated much of HIV behavioral intervention development, researchers and practitioners should keep an open mind about using multiple theories and constructs, including building on existing theories or adopting those from other disciplines (e.g., social work and sociology) [99]. Components of other successful programs (e.g., positive youth development) can also be used to further understand sexual risk behavior. Due to the importance of culture, theories that address the relevance of African American culture should also be explored. Further, researchers need to consider different levels of analysis in the interventions (family, community) and increase the occurrence of multidisciplinary work. This different approach may address the importance of norms/parental issues emerging from the literature on African American adolescent population. Testing new constructs, different levels of analysis, and interdisciplinary work may lead to the development of innovative interventions. For example, increasingly structural interventions that address social, economic, political and environmental factors that can also directly affect HIV risk are gaining popularity [100, 101].

Limitations of the Review

This review has several limitations. Although best efforts were made to find all relevant research articles, some may have been overlooked due to the search terms. Additionally, the authors only looked at research published in peer-reviewed literature and may have overlooked important practice-related literature. Finally, the authors only focused on significant findings. A better measure of a strong finding may have been the number of significant findings in proportion to the number of times the construct was examined.

Each person who scored the interventions made decisions about whether activities operationalized the various constructs, and this may have introduced potential bias. Although every attempt was made to be consistent across interventions and build consensus, there remained room for subjectivity. This subjectivity was limited by decision rule charts, discussion as a team, and revisiting each intervention after changes in scoring were made.

The calculated unit of measurement of dose was imprecise and is a limitation. If a 15-min activity addressed positive emotional reaction briefly, the full amount of time was credited to the construct. Further, we assumed that increased time devoted to a construct increases impact. However, there is no empiric evidence for any of the constructs about what dose is needed to affect change. It might be possible to adequately address a particular construct or constructs in a curriculum in a small amount of time. It is possible that it is the quality of the operationalization of constructs that is more important than dose. Also, there might be other ways to operationalize constructs other than through activities. For example, perceived norms could be increased by the group dynamic in addition to specific activities. Therefore, our measure of perceived norms may be an underestimate.

Further, studies that focused on subpopulations, such as detained, gay, or pregnant adolescents, who may be at the greatest risk, were not included and therefore this review may not be relevant to those African American adolescents at the greatest risk. Finally, other variables might exist that are important for African American youth; these may have been missed because of our article’s inclusion criteria. Additional variables have been identified by using other theoretical models (e.g., theories that address cultural relevance) or those variables found in the broader adolescent literature (e.g., risk factors such as an older sibling’s early sexual debut; working for pay more than 20 hours per week; and protective factors such as school connectedness, intention to remain a virgin, and increased motivation to avoid HIV, STD, and pregnancy) [9]. Further research is needed to explore whether these and other variables are also relevant for African American youth. Notwithstanding these methodological limitations, this review offers important insights on how the literature and evidence-based interventions correspond.

Conclusion

Our analysis showed that environmental conditions and perceived norms were frequently associated with sexual risk behaviors in the literature, while EBIs devoted considerable time to knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy. One possible conclusion is that it is not important to develop interventions that are based on theoretical constructs. Although environmental constraints seem correlated with risk behaviors, if an effective EBI does not address this construct maybe it is irrelevant? Should we trust the efficacy of EBI’s over theory and construct correlation research? This question is important for the field to answer. It comes up in studies that test the theoretical ‘mediators’ of interventions and find that many do not mediate [102].

However, we suggest these findings imply that while effective, EBIs might be complemented with activities that focus on additional important constructs that were identified in the literature, some of which exist at multiple ecological levels, to increase their effectiveness. Additionally, researchers should better assess the relationship between skill development and HIV risk behaviors.

Recommendations for Research and Practice

Our study showed environmental conditions and perceived norms are strongly associated with sexual risk behaviors; however the EBIs included minimal time to address these constructs. Based on the literature increasing environmental approaches and addressing perceived norms may improve EBIs for African American youth.

To better understand the influence of communication, decision-making, refusal, negotiation, and condom skills across populations, assessment tools are needed to measure the association between skills and sexual risk behavior outcomes. Such instruments would allow baseline assessment of the level of skills target populations possess, allow researchers to measure if interventions improve skills, and allow empirical evaluation of the relationship between skills and behavior. Guidance on how to develop measurements for communication, refusal, negotiation, and decision-making can be found in other disciplines (e.g., sociology, medical education) [103, 104].

Although we explored concordance of dose of theoretical constructs addressed in EBIs and the literature showing significant relationships to sexual risk behavior outcomes for African American youth, it is uncertain if constructs found frequently in the literature are ones that have the most impact on risk. A meta-analysis would assist in understanding what constructs are critical in changing behavior amongst African American youth.

This review focused on evidence-based interventions based on theories of behavior change. The potential value of youth development interventions, such as AIM, is emerging as an important area of study in the adolescent sexual health field. As discussed, while AIM is based on a strengths-based youth development theory, it has been shown to reduce sexual risk behavior outcomes [25]. Therefore, conducting a similar review to examine youth development literature may provide more insights into which additional constructs may be important for HIV prevention among African American youth.

Although improvements in HIV/AIDS treatment have been made, behavioral interventions remain our primary strategy for reducing HIV transmission. As we continue to see increases in the disproportionate burden of HIV in African American communities, culturally relevant HIV prevention interventions must be identified or developed, widely disseminated, and continually improved, based on research from that community. It is important for the field to review HIV prevention programs to ensure they are based on the most current theory and literature findings, thus increasing the likelihood of creating positive behavior change. Our analysis showed that the theoretical constructs of environmental conditions and perceived norms were most frequently associated with sexual risk behaviors in the literature; however EBIs devoted considerable time to the constructs of knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy. Reviews such as this one can help ensure that both research and practice are continuously improved and ensure that the public benefits from the research.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(SS-5):20–3.

Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6–10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2008. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2006. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2009.

Hawkins JD. Academic performance and school success: sources and consequences. In: Weissberg RP, Gullotta TP, Hampton RL, Ryan BA, Adams GR, editors. Healthy children 2010: enhancing children’s wellness. Vol 8. Issues in children’s and families’ lives ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual risk behaviors and academic achievement. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Healthyyouth/health_and_academics/index.htm. Accessed 5 January 2008.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance in adolescents and young adults (through 2007). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/index.htm. Accessed 3 May 2010.

Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics. November 23, 2009 2009:peds.2009-0674.

Kirby D, Laris B, Rolleri L. Sex and HIV education programs for youth: their impact and important characteristics. Washington, DC: Family Health International; 2006.

Lyles C, Kay L, Crepaz N, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–43.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Project. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/index.htm. Accessed 12 May 2009.

AED Center on AIDS and Community Health. Diffusion of effective behavioral interventions. Available at: http://www.effectiveinterventions.org/. Accessed 12 May 2009.

NIMH Office of AIDS Programs. Factors influencing behavior and behavior change: Final Report of the Theorists Workshop. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1991.

Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, et al. Evidence-based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of CDC’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(Suppl A):21–31.

Sogolow ED, Kay LS, Doll LS, et al. Strengthening HIV prevention: application of a research-to-practice framework. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(Suppl A):21–34.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tiers of evidence: a framework for classifying HIV behavioral interventions. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/tiers-of-evidence.htm. Accessed 30 June 2007.

Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–43.

St. Lawrence JS, Brasfield TL, Jefferson KW, et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention to reduce African American adolescents’ risk for HIV infection. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:221–37.

Jemmott JB III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among black male adolescents: effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:372–7.

Stanton B, Li X, Ricardo I, et al. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African-American youths. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:363–72.

Stanton B, Cole M, Galbraith J, et al. A randomized trial of a parent intervention: parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk behaviors, perceptions and knowledge. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:947–55.

DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:171–9.

Rotheram-Borus M, Song J, Gwadz M, et al. Reductions in HIV risk among runaway youth. Prev Sci. 2003;4:173–87.

Jemmott JB III, Jemmott LS, Fong G. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African-American adolescents: a randomized control trial. JAMA. 1998;279:1529–36.

Clark L, Miller K, Nagy S, et al. Adult identity mentoring: reducing sexual risk for African-American seventh grade students. J Adolesc Health. 2005; 37:337.e331–337.e310.

Marcus H, Nurius P. Possible selves. Am Psychol. 1986;41(9):954–69.

Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Bauer D, et al. Which comes first in adolescence—sex and drugs or depression? Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(3):163–70.

Millstein SG, Irwin CEJ, Adler NE, et al. Health-risk behaviors and health concerns among young adolescents. Pediatrics. 1992;89:422–8.

Donovan J, Jessor R, Costa F. Syndrome of problem behavior in adolescence: a replication. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;28:762–5.

Kandel D. Issues of sequencing of adolescent drug use and other problem behaviors. Perspect Adol Drug Use. 1989;3:55–76.

Block J, Block JH, Keyes S. Longitudinally foretelling drug usage in adolescence: early childhood personality and environmental precursors. Child Dev. 1988;59:336–55.

Jessor R, Chase JA, Donovan JE. Psychosocial correlates of marijuana use and problem drinking in a national sample of adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1980;70:604–13.

Zabin LS. The association between smoking and sexual behavior among teens in US contraceptive clinics. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:261–3.

Irwin CE, Millstein SC. Biopsychosocial correlates of risk-taking behaviors during adolescence: can the physician intervene? J Adolesc Health Care. 1986;7:825–965.

DiClemente R. Psychosocial determinants of condom use among adolescents. In: DiClemente R, editor. Adolescents and AIDS: a generation in Jeopardy. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992.

Buhi ER, Goodson P. Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: a theory-guided systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:4–21.

DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. A review of STD/HIV preventive interventions for adolescents: sustaining effects using an ecological approach. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(8):888–906.

Galbraith JS, Stanton B, Boekeloo B, et al. Exploring implementation and fidelity of evidence-based behavioral interventions for HIV prevention: lessons learned from the Focus on Kids diffusion case study. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(3):532–49.

Bunnell RE, Dahlberg L, Rolfs R, et al. High prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in urban adolescent females despite moderate risk behaviors. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1624–31.

Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Correlates of unprotected vaginal sex among African American female adolescents: importance of relationship dynamics. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(9):893–9.

DiIorio C, Dudley WN, Soet JE, et al. Sexual possibility situations and sexual behaviors among young adolescents: the moderating role of protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):528.e511–528.e520.

Williams KM, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of Chlamydia trachomatis among sexually active African-American adolescent females. Prev Med. 2002;35(6):593–600.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Harrington K, et al. Exposure to x-rated movies and adolescents’ sexual and contraceptive-related attitudes and behaviors. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1116–9.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Bernhardt JM, et al. A prospective study of exposure to rap music videos and African American female adolescents’ health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):437–9.

Sionean C, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Socioeconomic status and self-reported Gonorrhea among African American female adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(4):236–9.

Harper GW, Robinson WL. Pathways to risk among inner-city African-American adolescent females: the influence of gang membership. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27(3):383–404.

Ramirez-Valles J, Zimmerman MA, Newcomb MD. Sexual risk behavior among youth: modeling the influence of prosocial activities and socioeconomic factors. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39(3):237–53.

Lanctot N, Smith CA. Sexual activity, pregnancy, and deviance in a representative urban sample of African American girls. J Youth Adolesc. 2001;30(3):349–72.

Ramirez-Valles J, Zimmerman MA, Juarez L. Gender differences of neighborhood and social control processes: a study of the timing of first intercourse among low-achieving, urban, African American youth. Youth Soc. 2002;33(3):418–41.

Voisin DR. Victims of community violence and HIV sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescent males. J HIV AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2003;5(3/4):87–110.

Milhausen RR, Crosby R, Yarber WL, et al. Rural and nonrural African American high school students and STD/HIV sexual-risk behaviors. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(4):373–9.

Aronowitz T, Morrison-Beedy D. Resilience to risk-taking behaviors in impoverished African American girls: the role of mother-daughter connectedness. Res Nurs Health. 2004;27(1):29–39.

Dittus PJ, Jaccard J, Gordon VV. Direct and nondirect communication of maternal beliefs to adolescents: adolescent motivations for premarital sexual activity. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1999;29(9):1927–63.

Moore MR, Chase-Lansdale PL. Sexual intercourse and pregnancy among African American girls in high-poverty neighborhoods: the role of family and perceived community environment. J Marriage Fam Couns. 2001;63(4):1146–57.

Jaccard J, Dittus PJ, Gordon VV. Maternal correlates of adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28(4):159–65, 185.

Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. HIV/STD prevention benefits of living in supportive families: a prospective analysis of high risk African-American female teens. Am J Health Promot. 2002;16(3):142–145, ii.

Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. HIV/STD-protective benefits of living with mothers in perceived supportive families: a study of high-risk African American female teens. Prev Med. 2001;33:175–8.

Doljanac RF, Zimmerman MA. Psychosocial factors and high-risk sexual behavior: race differences among urban adolescents. J Behav Med. 1998;21(5):451–67.

McBride CK, Paikoff RL, Holmbeck GN. Individual and familial influences on the onset of sexual intercourse among urban African American adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(1):159–67.

Felton GM, Bartoces M. Predictors of initiation of early sex in black and white adolescent females. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(1):59–67.

Raine TR, Jenkins R, Aarons SJ, et al. Sociodemographic correlates of virginity in seventh-grade black and Latino students. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(5):304–12.

Romer D, Stanton B, Galbraith J, et al. Parental influence on adolescent sexual behavior in high-poverty settings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1055–62.

DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, et al. Parent-adolescent communication and sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescent females. J Pediatr. 2001;139(3):407–12.

Stanton B, Li X, Pack R, et al. Longitudinal influence of perceptions of peer and parental factors on African American adolescent risk involvement. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4):536–48.

Whitaker DJ, Miller KS. Parent-adolescent discussions about sex and condoms: impact on peer influences of sexual risk behavior. J Adolesc Res. 2000;15(2):251–73.

Whitaker DJ, Miller KS, May DC, et al. Teenage partners’ communication about sexual risk and condom use: the importance of parent-teenager discussions. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31(3):117–21.

DiIorio C, Kelley M, Hockenberry-Eaton M. Communication about sexual issues: mothers, fathers, and friends. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(3):181–9.

Miller KS, Levin ML, Whitaker DJ, et al. Patterns of condom use among adolescents: the impact of mother-adolescent communication. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(10):1542–4.

Li X, Feigelman S, Stanton B. Perceived parental monitoring and health risk behaviors among urban low-income African-American children and adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(1):43–8.

Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Infrequent parental monitoring predicts sexually transmitted infections among low-income African American female adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(2):169–73.

DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, et al. Parental monitoring: association with adolescents’ risk behaviors. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1363–8.

Li X, Stanton B, Feigelman S. Impact of perceived parental monitoring on adolescent risk behavior over 4 years. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(1):49–56.

Mandara J, Murray CB, Bangi AK. Predictors of African American adolescent sexual activity: an ecological framework. J Black Psychol. 2003;29(3):337–56.

Stanton BF, Li X, Galbraith J, et al. Parental underestimates of adolescent risk behavior: a randomized, controlled trial of a parental monitoring intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26:18–26.

Bachanas PJ, Morris MK, Lewis-Gess JK, et al. Predictors of risky sexual behavior in African American adolescent girls: implications for prevention interventions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(6):519–30.

Romer D, Stanton BF. Feelings about risk and the epidemic diffusion of adolescent sexual behavior. Prev Sci. 2003;4(1):39–53.

Kinsman SB, Romer D, Furstenberg FF, et al. Early sexual initiation: the role of peer norms. Pediatrics. 1998;102:1185–92.

Wills TA, Murry VM, Brody GH, et al. Ethnic pride and self-control related to protective and risk factors: test of the theoretical model for the Strong African American Families Program. Health Psyc. 2007;26(1):50–9.

Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, et al. Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: the influence of psychosocial factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(3):200–8.

Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Identification of strategies for promoting condom use: a prospective analysis of high-risk African American female teens. Prev Sci. 2003;4(4):263–70.

DiIorio C, Dudley WN, Kelly M, et al. Social cognitive correlates of sexual experience and condom use among 13- through 15-year-old adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3):208–16.

Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Condom use and correlates of African American adolescent females’ infrequent communication with sex partners about preventing sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(2):219–31.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Crosby R, et al. Gang involvement and the health of African American female adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):e57.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, McCree DH, et al. Dating violence and the sexual health of black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):e72.

Randolph SM, Banks DH. Making a way out of no way: the promise of Africentric approaches to HIV prevention. J Black Psychol. 1993;19:204–14.

Nobles W, Goddard L, Gilbert D. The African-centered behavior change model: The needed paradigm shift in HIV prevention for African American women. National HIV Prevention Conference. Atlanta, 2007.

Fullilove RE, Green L, Fullilove M. The Family to Family program: a structural intervention with implications for the prevention of HIV/AIDS and other community epidemics. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S63–7.

O’Donnell L, Stueve A, O’Donnell C, et al. Long-term reductions in sexual initiation and sexual activity among urban middle schoolers in the reach for health service learning program. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(1):93–100.

Bayne Smith M. Teen incentives program: evaluation of a health promotion model for adolescent pregnancy prevention. J Health Educ. 1994;25(1):24–9.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Adolescents and human immunodeficiency virus infection: the role of the pediatrician in prevention and intervention. Pediatrics. 2001;107:188–90.

Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD treatment guidelines: Special populations–adolescents. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/specialpops.htm#specialpops2. Accessed 8 July 2008.

Stratford DM, Williams K, Courtenay-Quirk C, et al. Addressing poverty as a risk for disease: recommendations from CDC’s consultation on microenterprise as HIV prevention. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:11.

Joint Committee on National Health Education Standards. National health education standards: achieving excellence. 2nd ed. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2007.

Kirby D, Lepore G, Ryan J. Sexual risk and protective factors: factors affecting teen sexual behavior, pregnancy, childbearing and sexually transmitted disease: which are important? Which can you change? Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2005.

Crosby R, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Correct condom application among African-American adolescent females: the relationship to perceived self-efficacy and the association to confirmed STDs. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3):194–9.

Deveaux L, Stanton B, Lunn S, et al. Reduction in human immunodeficiency virus risk among youth in developing countries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(12):1130–9.

Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J, et al. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1220–31.

Coates T, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372:669–84.

Blankenship K, Friedman S, Dworkin S, et al. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):59–72.

Gupta GR, Parkhurst JR, Ogden JA, et al. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:764–75.

O’Leary A, Jemmott LS, Jernmott JB. Mediation analysis of an effective sexual risk-reduction intervention for women: the importance of self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):S180–4.

McKinley R, Strand J, Ward L, et al. Checklists for assessment and certification of clinical procedural skills omit essential competencies: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2008;42(4):338–49.

Pick S, Givaudan M, Sirkin J, et al. Communication as a protective factor: evaluation of a life skills HIV/AIDS prevention program for Mexican elementary-school students. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19(5):408–21.

Jemmott JB III, Jemmott LS. Strategies to reduce the risk of HIV infection, sexually transmitted diseases, and pregnancy among African American adolescents. In: Resnick RJ, Rozensky RH, editors. Health psychology through the life span: practice and research opportunities. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1996. p. 395–422.

Rotheram-Borus M, Koopman S, Haignere C, et al. Reducing HIV sexual risk behaviors among runaway adolescents. JAMA. 1991;266:1237–41.

Pack RP, Crosby RA, St Lawrence JS. Associations between adolescents’ sexual risk behavior and scores on six psychometric scales: impulsivity predicts risk. J HIV AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2001;4(1):33–47.

Reitman DD, St. Lawrence JS, Jefferson KW, et al. Predictors of African American adolescents’ condom use and HIV risk behavior. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8(6):499–515.

Salazar LF, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Self-concept and adolescents’ refusal of unprotected sex: a test of mediating mechanisms among African American girls. Prev Sci. 2004;5(3):137–49.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Harrington K, et al. Body image and African American females’ sexual health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(5):433–9.

McCree DH, Wingood GM, DiClemente R, et al. Religiosity and risky sexual behavior in African-American adolescent females. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(1):2–8.

Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Activity of African-American female teenagers in black organisations is associated with STD/HIV protective behaviours: a prospective analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(7):549–50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Romero, L.M., Galbraith, J.S., Wilson-Williams, L. et al. HIV Prevention Among African American Youth: How Well Have Evidence-Based Interventions Addressed Key Theoretical Constructs?. AIDS Behav 15, 976–991 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9745-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9745-5