Abstract

We conducted a systematic review of behavioral change interventions to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV among women and girls living in low- and middle-income countries. PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and other databases and bibliographies were systematically searched for trials using randomized or quasi-experimental designs to evaluate behavioral interventions with HIV infection as an outcome. We identified 11 analyses for inclusion reporting on eight unique interventions. Interventions varied widely in intensity, duration, and delivery as well as by target population. Only two analyses showed a significant protective effect on HIV incidence among women and only three of ten analyses that measured behavioral outcomes reduced any measure of HIV-related risk behavior. Ongoing research is needed to determine whether behavior change interventions can be incorporated as independent efficacious components in HIV prevention packages for women or simply as complements to biomedical prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, women and girls are exceptionally vulnerable to HIV infection. Although women represent about half of all people living with HIV, in Sub-Saharan Africa where the pandemic is concentrated, women comprise 59 percent of people living with HIV infection [1]. Young women become susceptible to HIV at an early age—in some areas the prevalence of infection among women between 15 and 24 years is more than twice that of young men [1, 2]. Women living in lower income countries are particularly at risk, as extreme poverty and other structural factors such as gender inequities, lack of education, and violence reduce their ability to control health outcomes or access HIV-related information and services [3].

HIV prevention efforts in women have been hampered by the generally disappointing results of biomedical prevention trials. Candidate female-controlled biomedical prevention strategies, such as cervical barriers and microbicides, have not yet shown efficacy in randomized trials [4–7]. Thus, prevention focuses mainly on male-controlled prevention methods such as male circumcision and condoms. Male circumcision, although highly effective at preventing female-to-male sexual transmission, has yet to be shown to directly reduce women’s risk of infection (although reductions in HIV prevalence will indirectly benefit women) [8, 9]. Male and female condoms are effective at preventing sexual transmission of HIV but both require male partner knowledge and consent [10, 11]. Finally, although improved diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STI) may be an important strategy to reduce HIV transmission and deleterious effects of other STIs [12], women in the poorest parts of the world may not have access to or utilize sexual and reproductive health services [13]. Thus, in the absence of an effective vaccine or alternative female-controlled biomedical prevention method, HIV prevention efforts for women currently focus on the mainstay of prevention strategies—behavior change [14].

Behavioral strategies to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV include programs that aim to delay age of sexual debut, decrease the number of sexual partners and concurrent partnerships, increase the proportion of protected sexual acts, increase acceptance of voluntary counseling and testing (VCT), and improve adherence to successful biomedical prevention strategies, such as condom use [15]. These interventions can focus on the individual, peer, couple, group, family, institution, or the community. In addition, they vary widely in duration, intensity, and delivery. In order to produce measureable population-level changes in HIV infection, behavioral interventions need to produce change in enough people for a sufficient time to impact transmission dynamics [15]. Behavioral interventions targeting men who have sex with men [16], sexually transmitted disease clinic patients [17], heterosexual African Americans [18], sexually experienced adolescents in the United States [19], and people living with HIV [20] are effective in reducing self-reported sexual risk behaviors. In addition, meta-analytic reviews suggest that interventions that are targeted to specific race or gender groups, include skills training, and that are based on behavioral theory demonstrate efficacy, again, when measured by self-report (for review of meta-analyses, see Noar 2008) [21].

Despite numerous behavior change interventions that have been evaluated since the beginning of the HIV epidemic more than 25 years ago, there is a notable paucity of data on the direct effect of such interventions on HIV incidence. Examining HIV infection as the outcome in efficacy trials is critical for several reasons. Most obviously, because the ultimate objective of such interventions is to prevent new HIV infections, evaluating the effect on HIV incidence is the only way to measure program impact directly. Furthermore, reported sexual behaviors can be subject to reporting and recall bias and may be inconsistent with what is known about population-level HIV infection prevalence [22, 23]. Although greater resources are often needed to conduct evaluation trials with HIV infection as the endpoint, they are generally acceptable to study participants and have been utilized in several large randomized trails of behavioral interventions [24–27].

To date, no reviews have been conducted that summarize the effect of behavioral interventions for HIV prevention in women and girls in the developing world. Recently, the results of several large randomized trials of the effect of behavioral interventions on HIV incidence have been published, the data from which now permit a more focused review of these trials for HIV prevention in women [28–30]. Given the increased risk of HIV incidence among women and girls [1–3] our goal was to systematically review and summarize behavioral change interventions to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV among women and girls living in low- and middle-income countries.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycInfo, the Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Web of Science, Sociological Abstracts, the National Library of Medicine Gateway, African Index Medicus, the Regional Index for Latin America and the Caribbean (Virtual Health Library) and IndMed (the regional database for Indian biomedical journals) for articles and abstracts meeting our inclusion criteria as of March 2, 2009. There were no language restrictions to the search. We developed a customized search strategy for each database relying on the database’s controlled vocabulary or index (e.g., medical subject headings (MeSH)) or free text terms. In most cases, search strategies combined terms for (1) HIV infection, (2) behavior or counseling, (3) prevention, and (4) study design restrictions (randomized controlled designs or quasi-experimental). In PubMed/MEDLINE, we searched for clinical trials using an adapted version of Cochrane’s “Highly Sensitive Search Strategy” for identifying randomized controlled trials [31]. Search strategies for each database are available from the authors.

To limit publication bias and identify unpublished studies, we searched the Current Controlled Trials Register, the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal, clinicaltrials.gov, and Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects (CRISP) to identify unpublished studies meeting the inclusion criteria. We conducted a cited reference search with key articles, scanned reference lists of eligible articles and reviews, and searched the electronic conference proceedings of recent HIV/AIDS-related conferences (Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, International Society for STD Research annual meetings, and International AIDS Society annual meetings). We contacted three study authors who provided additional information about the trials (including effect estimates among women [27, 29]).

Trial Selection

Eligible trials were those that (1) were published in 1990 or after; (2) used randomized controlled designs (individual or community) or quasi-experimental prospective designs with a control group; (3) evaluated behavioral interventions focusing on sexual transmission of HIV; (4) were conducted in low- and middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank; (5) were conducted either entirely in women or reported gender-stratified effect estimates (either in the manuscript or shared by study authors); and (6) reported HIV incidence or cumulative risk in the intervention and comparison arms or an overall relative measure of effect (e.g., incidence rate ratios (IRR), risk ratios (RR)). Although effect estimates adjusted for confounders were preferred, analyses with only unadjusted (“crude”) estimates were eligible for inclusion.

We first examined the citations from the literature search to eliminate obviously ineligible studies (e.g., those conducted in men, in high-income countries, pertaining to intravenous transmission, or inappropriate article types such as reviews or commentaries). Abstracts were specifically searched for mention of a behavioral intervention tested against a control intervention with biological outcomes. Report of any sexually transmitted disease outcome in the abstract such as incident gonorrhea or chlamydia infections automatically warranted a full length review of the article to determine if HIV testing was conducted. We then conducted a detailed manual review of full length articles to determine eligibility. As we wanted to estimate the effect of interventions on HIV incidence, repeated cross-sectional studies [32] or studies only reporting prevalence were not considered eligible [33].

In two instances, results from individual-level analyses in a community randomized trial were considered separately from the primary community-level analysis. Although such individual-level analyses are subject to selection bias and could potentially negate the benefits of randomization, these reports allow examination of the direct effect of the interventions on the individuals who actually received them in contrast to the general effect on residents residing in communities where the interventions took place. Furthermore, the individual analyses independently meet study inclusion criteria as they are prospective in nature and have control groups. In these cases, we present the community- and individual-level analyses as single interventions with two methods of analyses. We refer to the community-level analysis as the primary analysis and to the individual-level analysis as a secondary analysis.

Quality Assessment

We assessed trial quality using a “component approach” after completion of the literature search; to prevent exclusion of potentially valid information study quality was not part of the inclusion criteria [34]. We assessed dimensions of internal validity such as allocation method, type of control group, participation rate, attrition bias, and type and appropriateness of statistical analyses (e.g., intent to treat). We also considered the role of selection bias for each study.

Data Extraction

For each eligible article or abstract, a single investigator (SM) abstracted the most adjusted measure of effect on the primary outcome of HIV incidence (e.g., IRR, RR). In cases where only the incidence rates in each study arm were presented, we computed IRRs and 95% confidence intervals using standard methods [35]. Although the incidence rate ratio was the preferred measure of effect; one study reported a RR [30, 36], which we assumed approximated the IRR given the rarity of the outcome and that the “exposure” to the intervention should only negligibly affect the person-time at risk [37]. Alternatively, if the exposure did affect the average time at risk, we would expect the RR to be closer to the null than the IRR in which case the RR would be more conservative [37]. In one study, no events were reported in the intervention arm so we computed an exact P-value for the intervention effect with person-time information obtained from the study authors [34, 38].

We also examined the effect of the interventions on incident STIs as secondary outcomes as well as the effect of the interventions on HIV-related risk behavior such as number of partners and condom use. In cases where multiple behavioral measurements were assessed in a single study over time, we examined the effect with the longest follow-up period. We also abstracted data including trial year, location, and population as well as details about the intervention (e.g., type, length, audience, behavioral theory (if specified), and nature of the control group).

Descriptive Analysis

We anticipated that few studies would meet the inclusion criteria and that the study populations and interventions would be substantially variable, precluding consideration of summary measures of effect. Given the wide variation in intervention type and intensity, we decided not to proceed with meta-analytic methods. Thus, we present descriptive information about each unique intervention as well as a forest plot of measures of effect generated with Stata software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Literature Search

The results of the literature search are presented in Fig. 1. We identified 3,864 citations from electronic databases of which 3,265 were excluded based on title examination and 551 were excluded based on abstract-level review. Forty-eight full-length articles were reviewed in detail. During the entire process, we excluded nearly 200 evaluations of behavioral interventions in women and girls in low- and middle-income countries that did not evaluate HIV infection. One report with no HIV seroconversions in either study arm was excluded [39]. Eight articles from the literature search met the inclusion criteria; addition of another three articles from reference list examinations yielded 11 analyses for inclusion in the review reporting on eight unique interventions (Table 1). All but one [36] of the reports were published in peer-reviewed journals.

Several of the interventions were described in multiple articles from which we abstracted information. For example, the female-only estimate of the intervention described in Pronyk et al. was obtained from a separate article because the estimate in the original article was combined for men and women [30, 40]. For two interventions, we included both the individual-level and community-level analysis in the review [27, 29, 41]. In one case (Gregson et al.) the individual-level estimate was from the same article as the community-level estimate [29]. We also included two estimates from the MEMA kwa Vijana study in Tanzania, one was after 3 years of follow-up and the other was after 6–8 years of follow-up [36, 42]. Information on the long-term follow-up of the MEMA kwa Vijana trial was also abstracted from a technical briefing paper available on the study website with a more detailed presentation of the long-term results [43].

Study Characteristics

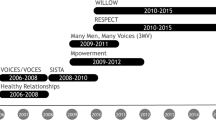

Of the eight unique interventions, six (75%) were conducted in Africa, one was conducted in India, and one was conducted in Mexico. Community randomized controlled trials (C-RCT) were the most common study design (five of eight trials), and together the trials enrolled 42,053 participants. Two trials were targeted toward female sex workers (FSWs) [38, 44], and two were targeted toward adolescents or young adults aged 15–26 years [28, 36, 42]. With one exception, study participants were followed for at least a year and on average for approximately 2.6 years. A study evaluating a brief counseling session for sex workers in Mexico followed participants for 6 months [38].

Most studies used randomized designs, reported participation rates over 70%, and had active control groups receiving a separate prevention intervention (Table 2). Retention rates varied from more than 90% over 1 year in Indian female sex workers to 21–24% over three to 4 years among men and women in Uganda [27, 44]. Two reports had significant methodological limitations. The first, Bhave et al. examined the effect of an educational and motivational intervention for female sex workers and brothel madams in two red light districts in Mumbai [44]. The red light districts were assigned to the intervention or control by convenience (although the authors note similarities between the areas in reported behaviors and STI prevalence) and there was no adjustment for this clustering in the analysis. Another study evaluated the effect of VCT in Uganda by allowing participants the choice to receive testing results and therefore self-selection into the study arms [45]. Participants were subsequently followed for a year to determine the effect of receiving testing results on HIV incidence. Despite these limitations, these reports were included in the review for completeness.

Types of Interventions

The types of interventions were highly variable (Table 3). They ranged from a single enhanced counseling session in FSWs to the intensive 50-h Stepping Stones program, which used a participatory learning approach among young men and women ages 15–26 [28, 38]. Only two interventions were targeted towards individuals, one was a study of VCT where individuals could choose to receive their testing results alone or as a couple and the other was among FSWs in Mexico (Mujer Segura) [38, 45]. The remaining six interventions were targeted towards groups or combinations of individuals, groups, and/or communities. The study among FSWs in India targeted sex workers as well as brothel madams—each participated in a separate educational and motivational program over 6 months [44]. Two interventions were targeted towards adolescents or young adults, MEMA kwa Vijana in Tanzania (adolescents in years 5–7 of primary school) and Stepping Stones (men and women 15–26 years old) [28, 42].

All of the interventions directly addressed HIV-related risk with some combination of education, motivational counseling, skills building, condom promotion, risk reduction planning, and/or improved sexual and reproductive health services. However, Pronyk et al. added a microfinance component to the Sisters for Life gender and HIV curriculum; Gregson et al. also planned to implement microcredit income generating projects but they could not do so due to the economic climate in Zimbabwe [29, 30]. In general, the community randomized trials implemented a diverse suite of targeted and community activities including small and large group discussions, community events such as drama and video shows for community residents, and social marketing of condoms. Communication and condom skills-building or role-playing activities were a component of all but two of the interventions [29, 45].

Effect on HIV Infection

Only 2 of 11 analyses showed a significant effect on HIV incidence among women (Fig. 2). Note that the Patterson et al. estimate among FSWs in Mexico is not shown on the plot because there were no seroconversions in the intervention arm and only four seroconversions in the control arm (P = 0.07) [38]. A 6 month program of group educational and motivational sessions for FSWs and brothel madams in two red-light districts in Mumbai (Bombay) was successful at reducing HIV incidence over the 1 year follow-up period (IRR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.72) [44]. The intervention for FSWs consisted of educational and motivational videos, small group discussions, and the use of pictorial educational materials focusing on STIs, AIDS, and condom use. Women were instructed on correct use of the male condom and were encouraged to educate their clients about the importance of condom use, as well as refuse clients who did not use condoms. The intervention for madams focused on the importance and economic benefits of maintaining the health of sex workers. Lubricated condoms were only given to the intervention group and were not available to FSWs in the control arm. Use of condoms was extremely low at baseline—only 1–2% of FSWs asked clients to use condoms—and less than 1% knew not to use oil-based lubricants (e.g., hair oil), which was a common practice. The intervention also significantly affected condom use (discussed below).

Forest plot of study specific estimates of reduction in HIV incidence in women following implementation of a behavioral intervention. Patterson [38] not shown. Quigley [41] and Gregson [29] are individual-level analyses of community randomized trials described in Kamali [27] and Gregson [29], respectively. The estimate of HIV incidence for Pronyk [30] among women was presented in a separate article, Hargreaves et al. [40]. The estimate for HIV incidence among women for Kamali [27] and Gregson [29] was provided by study authors. The estimate presented in Doyle [36] is the 6–8 year follow-up analysis of the study described in Ross [42]. This study presented a relative risk; we assumed that the relative risk approximated the incidence rate ratio (see methods)

The individual-level secondary analysis of sexually active, initially HIV-seronegative women in the Masaka, Uganda trial showed that attendance at any study-related activity in the past year reduced HIV incidence (IRR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.19, 0.89) [41]. Intervention activities included meetings, videos, and dramas focusing on information, education, and communication [27]. The effect was diluted when those who reported not being sexually active were included (IRR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.24–1.14), and the community-level analysis of women living in study communities failed to show any effect [27, 41]. The remaining analyses clustered near the null value of no effect on HIV incidence.

Effect on Secondary Outcomes: STIs and HIV-Related Risk Behavior

Six of the 11 analyses reported outcomes in STIs other than HIV and 10 assessed self-reported HIV-related risk behavior (Table 4). Only one analysis (Bhave et al. among FSWs in India) reduced the incidence of HIV and STIs, and reduced reported risk behavior. This intervention significantly reduced the incidence of syphilis antibodies and hepatitis B surface antigen (unadjusted IRRs 0.35 (95% CI: 0.17, 0.72) and 0.30 (95% CI: 0.14, 0.66), respectively) and the percentage of FSWs reporting always using a condom with clients increased from 3 to 28 percent after the intervention, compared to a decrease in the control group (from 3 to 0 percent) [44].

The information, education, and communication intervention in Masaka, Uganda had mixed results on STIs and no effect on behavior [27, 41]. Although the individual-level analysis among sexually active women demonstrated reduced HIV incidence, the effect on STIs was not available in this sub-group [41]. In the community-level analysis, the intervention reduced herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) incidence (IRR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.43–0.97), although no effect was found for active syphilis, gonorrhea or chlamydia prevalence [27]. This study also included a third study arm combining the same behavioral intervention plus improved management of STIs, which did not detect a similar effect on HSV-2 [27]. Significant behavior changes were not observed in either the individual-level analysis among women or the community-level analysis among both men and women.

The remaining analyses, none of which had an effect on HIV, had inconsistent effects on STIs and self-reported behavior. Three analyses did not reduce self-reported risk behavior and did not measure STIs other than HIV [29, 30, 45]. In the MEMA kwa Vijana trial, there was no reduction of HSV-2, syphilis, chlamydia or gonorrhea prevalence among women either after 3 years of follow-up or after 6–8 years of follow-up [36, 42, 43]. Although the intervention had no effect on most behavioral outcomes in either follow-up period, in the long term follow-up, condom use at the last sex with a non-regular partner in the past year among female adolescents increased (prevalence ratio = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.69). The Stepping Stones intervention reduced HSV-2 incidence overall (adjusted IRR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.47, 0.97) but among women the effect was not statistically significant (unadjusted IRR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.47, 1.03) [28]. There was no effect on reported sexual risk behaviors. Finally, the Mujer Segura intervention in FSWs in Mexico did not reduce the incidence of syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia individually, but did have an effect on a composite STI measure, including HIV infection (unadjusted IRR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.32, 0.95). Condom use increased 27% among FSWs in Mexico after the Mujer Segura intervention, compared to 17.5% among controls (P < 0.01).

Discussion

This review suggests that behavioral interventions to prevent HIV infection in women and girls in low- and middle-income countries have been limited in their success. Of the interventions we identified, only two had statistically significant effects on HIV incidence and only one, which had significant methodological shortcomings, simultaneously reduced risk behavior, HIV incidence, and STIs [44]. It is challenging to determine specific features of these two successful interventions given the dramatic variability in the intensity, duration, and delivery of the interventions. The intervention among FSWs in India may have been successful because both FSWs and brothel madams were targeted [44]. However, the unavailability of free lubricated male condoms in the control group, the frequency of inappropriate lubricant use at baseline, and other methodological limitations suggest that the success of the intervention may have been at least partially attributed simply to the availability of quality lubricated condoms. The successful study in Uganda examined self-reported attendance at intervention activities among sexually active women [41]. There were no effects of intervention activities on sexual behavior or any effect on HIV in the community-level analysis, although the effect on sexually active women was statistically significant even when subdivided by type of activity (e.g., meeting, video, drama). In both cases, elements of the successful interventions were similar to those in other unsuccessful interventions.

Despite several summary reports finding that behavioral interventions were effective in changing self-reported risk behavior in a variety of other populations [16–19, 19, 21, 46], the interventions for women and girls in low- and middle income countries included in this review did not have large impacts on behavior. Only three of ten reports in this review that measured behavioral outcomes reduced any measure of HIV risk behavior; in one case (the long term evaluation of MEMA kwa Vijana) only one of 10 behavioral markers in women showed any improvement (condom use with a non-regular partner) [36, 43]. However, it is important to note that our review did not include all studies of behavioral interventions for women and girls in lower income countries only those that measured the effect on HIV incidence were included. Regardless, the reliability of self-reported sexual behavior is unknown.

There are several possible explanations for the inability of the interventions in this review to reduce sexual risk behavior in women and girls. First, it is possible that the interventions did not change risk behavior at all or that short term effects were not sustained over the follow-up period. Second, women’s individual behavior is not always high-risk, and their individual susceptibility may be entirely driven by their partner or husband’s behavior, which is often out of their immediate control. Behavioral interventions targeting individual behavior change may be ineffective in these situations as women may not perceive themselves to be at risk [15]. Similarly, sexual network and group-level determinants may be more important drivers of transmission in a population [47]. The time between the end of one sexual partnership and the beginning of the next (the “gap”) is gaining attention for its importance in facilitating the spread of STIs, especially when one partnership begins prior to the end of an STI’s infectious period or when partnerships overlap in concurrency [48, 49]. Finally, perhaps structural factors such as gender inequities further up the causal chain that drive risk behavior are more important to address than individual behavior to incite population-level behavior change [3]. These reasons, and undoubtedly others, may explain why the reports in this review had limited efficacy changing sexual behavior.

The effect of the interventions on HIV, STIs and reported risk behavior were often inconsistent. However, the expectation that behavioral change interventions should consistently reduce both HIV and other STIs may be an oversimplification of complex pathogen transmission dynamics. Modeling studies have suggested that behavioral strategies have different impacts on HIV and STIs—reducing the number of partners may be more important for highly infectious STIs such as gonorrhea, whereas condom use may be more effective than reducing the number of partners at reducing HIV transmission risk [50]. The variability of infectivity across STIs as well as the variability of HIV infectivity given disease stage and cofactors like circumcision and the presence of STI co-infections [51] suggests that all sexual risk behaviors are not the same in terms of HIV/STI transmission, and that a more focused selection of “targeted” behaviors for a specific pathogen may increase the chances of success for behavioral interventions.

This review, like all systematic reviews, is subject to important limitations. All analyses that reported any biological outcome (e.g., HIV, gonorrhea, Chlamydia) in the abstract were selected for detailed review. However, if HIV incidence was measured but HIV or other biological outcomes were not mentioned in the abstract, they would have been excluded at the abstract review phase. We may have also missed relevant studies from databases not searched. We included one meeting abstract which had not yet been peer-reviewed, and we included both individual- and community-level analyses from the same interventions as well as both the short and long-term follow-up from one study: the MEMA kwa Vijana study. Although multiple estimates from the same study are typically not included in systematic reviews, we included them for completeness and because they met the inclusion criteria. We allow the reader to determine the weight of the evidence they provide. We focused only on HIV incidence, so studies using repeated cross-sectional designs with prevalence estimates were excluded. Finally, not all of the included reports were powered to detect an effect on HIV incidence, so the precision of the effect estimates varies dramatically, and some reports only provided unadjusted measures of effect. Despite these shortcomings, this review is the first, to our knowledge, to summarize the effect of behavioral interventions to prevent HIV infection in women and girls in the developing world.

At least two large studies of behavioral interventions with HIV incidence as an outcome are currently in progress. The community population opinion leader (C-POL) program was evaluated in five countries (China, India, Russia, Peru, Zimbabwe) and has completed data collection. Although the HIV results had not been released at the time of this writing there was no effect of the intervention on a combined sexually transmitted infection outcome (including HIV) [52]. In addition, Project Accept is a trial of community based VCT versus standard clinic based VCT for the prevention of HIV infection in South Africa, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Thailand [53]. Results are expected in 2011. In addition to these two trials, the Regai Dzive Shiri community randomized trial in Zimbabwe, which evaluated a multi-component prevention intervention for adolescents based on peer education, was recently completed [54, 55]. Although the community randomized study design was modified midway to serial cross-sectional assessments of prevalence (which precluded it from inclusion in this review), they found that the intervention had no effect on HIV prevalence in young men or women residing in study communities [55]—adding to the growing body of literature reporting on trials of behavioral interventions with no effect on HIV infection.

Given these findings, important research and prevention gaps remain for HIV prevention programmers. The diminishing hope that a single behavioral or biomedical prevention intervention will be sufficient to address the growing HIV pandemic has heralded a programmatic shift towards combination HIV prevention programming [56–59]. By combining interventions with partial effectiveness targeted to populations most at risk, combination intervention packages should address both the biological and behavioral factors associated with transmission as well as the social and structural determinants that can aid or impede the success of HIV prevention programming [56–59]. Under this new paradigm, behavioral approaches to HIV prevention are critical components of prevention packages for both women and men, as a strategy to reduce high-risk sexual behavior and inform and educate the community, but also as a mechanism to improve the uptake, adherence, and proper use of biomedical intervention methods.

This review has highlighted the reality that current behavior change interventions, by themselves, have been limited in their ability to control HIV infection in women and girls in low- and middle-income countries, at least over short follow-up periods of 1–3 years. However, there is an ethical responsibility to educate women about HIV infection and offer accurate prevention and risk reduction information even in the absence of clear data on effectiveness. Yet how to incorporate behavioral change programs into HIV prevention packages is unclear. Clearly, elements of behavior change (e.g., information, motivation, skills) are necessary to complement biomedical prevention strategies to ensure their successful scale up and prevent risk compensation [60]. However, ongoing studies are needed to determine whether behavior change interventions can be incorporated as efficacious components in a prevention package for women or, more conservatively, simply as supportive programs for biomedical prevention strategies.

References

UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva 2008.

Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people’s sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS. Sep 23 2005;19(14):1525–34.

Krishnan S, Dunbar MS, Minnis AM, Medlin CA, Gerdts CE, Padian NS. Poverty, gender inequities, and women’s risk of human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:101–10.

Padian NS, van der Straten A, Ramjee G, et al. Diaphragm and lubricant gel for prevention of HIV acquisition in southern African women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Jul 21 2007;370(9583):251–61.

Skoler-Karpoff S, Ramjee G, Ahmed K, et al. Efficacy of Carraguard for prevention of HIV infection in women in South Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. Dec 6 2008;372(9654):1977–87.

Peterson L, Nanda K, Opoku BK, et al. SAVVY (C31G) gel for prevention of HIV infection in women: a Phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(12):e1312.

Halpern V, Ogunsola F, Obunge O, et al. Effectiveness of cellulose sulfate vaginal gel for the prevention of HIV infection: results of a Phase III trial in Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(11):e3784.

Turner AN, Morrison CS, Padian NS, et al. Men’s circumcision status and women’s risk of HIV acquisition in Zimbabwe and Uganda. AIDS. Aug 20 2007;21(13):1779–89.

Wawer M, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Trial of male circumcision in HIV + men, Rakai, Uganda: effects in HIV+ men and in women partners. Paper presented at: 15th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2008; Boston, MA.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Workshop Summary: scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention 2000.

French PP, Latka M, Gollub EL, Rogers C, Hoover DR, Stein ZA. Use-effectiveness of the female versus male condom in preventing sexually transmitted disease in women. Sex Transm Dis. May 2003;30(5):433–9.

Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Aug 26 1995;346(8974):530–6.

Kiwanuka SN, Ekirapa EK, Peterson S, et al. Access to and utilisation of health services for the poor in Uganda: a systematic review of available evidence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. Nov 2008;102(11):1067–74.

Kalichman SC. Time to take stock in HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Behav. May 2008;12(3):333–4.

Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. Aug 23 2008;372(9639):669–84.

Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, et al. A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Jun 1 2005;39(2):228–41.

Crepaz N, Horn AK, Rama SM, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk sex behaviors and incident sexually transmitted disease in black and Hispanic sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in the United States: a meta-analytic review. Sex Transm Dis. Jun 2007;34(6):319–32.

Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, Rutherford G. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. Aids. Jun 19 2008;22(10):1177–94.

Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. 302002:S94–105.

Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. Jan 9 2006;20(2):143–57.

Noar SM. Behavioral interventions to reduce HIV-related sexual risk behavior: review and synthesis of meta-analytic evidence. 122008:335–53.

Plummer ML, Ross DA, Wight D, et al. “A bit more truthful”: the validity of adolescent sexual behaviour data collected in rural northern Tanzania using five methods. Sex Transm Infect. Dec 2004;80 Suppl 2:ii49–56.

Lagarde E, Auvert B, Chege J, et al. Condom use and its association with HIV/sexually transmitted diseases in four urban communities of sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. Aug 2001;15 Suppl 4:S71–78.

Cowan FM, Langhaug LF, Mashungupa GP, et al. School based HIV prevention in Zimbabwe: feasibility and acceptability of evaluation trials using biological outcomes. AIDS. Aug 16 2002;16(12):1673–8.

Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr., et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA. Oct 7 1998;280(13):1161–7.

Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T. Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet. Jul 3–9 2004;364(9428):41–50.

Kamali A, Quigley M, Nakiyingi J, et al. Syndromic management of sexually-transmitted infections and behaviour change interventions on transmission of HIV-1 in rural Uganda: a community randomised trial. Lancet. Feb 22 2003;361(9358):645–52.

Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2008;337:a506.

Gregson S, Adamson S, Papaya S, et al. Impact and process evaluation of integrated community and clinic-based HIV-1 control: a cluster-randomised trial in eastern Zimbabwe. PLoS Med. Mar 27 2007;4(3):e102.

Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. Dec 2 2006;368(9551):1973–83.

The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated September 2008]. 2008; Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Pettifor AE, Kleinschmidt I, Levin J, et al. A community-based study to examine the effect of a youth HIV prevention intervention on young people aged 15–24 in South Africa: results of the baseline survey. 102005:971–80.

Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. The Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group. Lancet. Jul 8 2000;356(9224):103–12.

Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Publishing Group, BMJ Books; 2001.

Rothman K. Epidemiology, an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

Doyle A, Ross DA, Maganja K, Changalucha J, Hayes R, Team. atMkVT. Long-term impact of a behavioral change intervention on HIV, STI, knowledge, attitudes, and reported sexual behaviors among young people in rural Mwanza, Tanzania: results of a community randomized trial. 16th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. Montreal, Canada 2009.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

Patterson TL, Mausbach B, Lozada R, et al. Efficacy of a brief behavioral intervention to promote condom use among female sex workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Am J Public Health. Nov 2008;98(11):2051–7.

Archibald CP, Chan RK, Wong ML, Goh A, Goh CL. Evaluation of a safe-sex intervention programme among sex workers in Singapore. Int J STD AIDS. Jul–Aug 1994;5(4):268–72.

Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Morison LA, et al. Explaining continued high HIV prevalence in South Africa: socioeconomic factors, HIV incidence and sexual behaviour change among a rural cohort, 2001–2004. AIDS. Nov 2007;21 Suppl 7:S39–48.

Quigley MA, Kamali A, Kinsman J, et al. The impact of attending a behavioural intervention on HIV incidence in Masaka, Uganda. AIDS (London, England). 2004;18(15):2055–63.

Ross DA, Changalucha J, Obasi AI, et al. Biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: a community-randomized trial. Aids. Sep 12 2007;21(14):1943–55.

Long-term Evaluation of the MEMA kwa Vijana Adolescent Sexual Health Programme in Rural Mwanza, Tanzania: a Randomised Controlled Trial. Technical Briefing Paper: No. 7 2008; http://www.memakwavijana.org/images/stories/Documents/mkv_technical_brief.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2009.

Bhave G, Lindan CP, Hudes ES, et al. Impact of an intervention on HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, and condom use among sex workers in Bombay, India. Aids. Jul 1995;9 Suppl 1:S21–30.

Matovu JK, Gray RH, Makumbi F, et al. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing acceptance, sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. Mar 25 2005;19(5):503–11.

Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Jul 2002;30 Suppl:S94–105.

Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and transmission dynamics in networks. Soc Netw. 1995;17:299–318.

Aral SO. Just one more day: the gap as population level determinant and risk factor for STI spread. Sex Transm Dis. May 2008;35(5):445–6.

Chen MI, Ghani AC, Edmunds J. Mind the gap: the role of time between sex with two consecutive partners on the transmission dynamics of gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis. May 2008;35(5):435–44.

Pinkerton SD, Layde PM, DiFranceisco W, Chesson HW. All STDs are not created equal: an analysis of the differential effects of sexual behaviour changes on different STDs. Int J STD AIDS. May 2003;14(5):320–8.

Powers KA, Poole C, Pettifor AE, Cohen MS. Rethinking the heterosexual infectivity of HIV-1: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. Sep 2008;8(9):553–63.

Pequegnat W, NIMH Collaborative HIV/STD Prevention Trial Group. Results of the RCT to Test the Community Popular Opinion Leader (C-POL) Intervention in Five Countries. Paper presented at: XVII International AIDS Conference 2008; Mexico City.

Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Morin SF, Fritz K, et al. Project Accept (HPTN 043): a community-based intervention to reduce HIV incidence in populations at risk for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Dec 1 2008;49(4):422–31.

Cowan FM, Pascoe SJ, Langhaug LF, et al. The Regai Dzive Shiri Project: a cluster randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a multi-component community-based HIV prevention intervention for rural youth in Zimbabwe-study design and baseline results. Trop Med Int Health. Oct 2008;13(10):1235–44.

Cowan F. Results of the Regai Dzive Shiri Project: Personal Communication.; May 2009.

Cates W, Jr., Hinman AR. AIDS and absolutism—the demand for perfection in prevention. N Engl J Med. Aug 13 1992;327(7):492–4.

UNAIDS. Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention: Towards Universal Access. Geneva 2007.

Piot P, Bartos M, Larson H, Zewdie D, Mane P. Coming to terms with complexity: a call to action for HIV prevention. Lancet. Sep 6 2008;372(9641):845–59.

Merson M, Padian N, Coates TJ, et al. Combination HIV prevention. Lancet. Nov 22 2008;372(9652):1805–6.

Eaton LA, Kalichman S. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. Dec 2007;4(4):165–72.

Rural AIDS and Development Action Research Programme. Social interventions for HIV/AIDS, intervention with microfinance for AIDS and gender equity. IMAGE Study Monograph No 2: Intervention 2002; http://web.wits.ac.za/NR/rdonlyres/3C2A3B30-DE20-40E0-8A0A-A14C98D0AB38/0/Intervention_monograph_picspdf.pdf. Accessed 18 March 2009.

Obasi AI, Cleophas B, Ross DA, et al. Rationale and design of the MEMA kwa Vijana adolescent sexual and reproductive health intervention in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. AIDS Care. May 2006;18(4):311–22.

Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. A cluster randomized-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of Stepping Stones in preventing HIV infections and promoting safer sexual behaviour amongst youth in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop Med Int Health. Jan 2006;11(1):3–16.

Patterson TL, Orozovich P, Semple SJ, et al. A sexual risk reduction intervention for female sex workers in Mexico: design and baseline characteristics. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv. 2006;5(2):115–37.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). We are grateful to Dr. Temina Madon for helpful comments on the manuscript and Dr. Nick Jewell for statistical advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCoy, S.I., Kangwende, R.A. & Padian, N.S. Behavior Change Interventions to Prevent HIV Infection among Women Living in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav 14, 469–482 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9644-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9644-9