Abstract

The present investigation attempted to quantify the relationship between alcohol consumption and unprotected sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). A comprehensive search of the literature was performed to identify key studies on alcohol and sexual risk behavior among PLWHA, and three separate meta-analyses were conducted to examine associations between unprotected sex and (1) any alcohol consumption, (2) problematic drinking, and (3) alcohol use in sexual contexts. Based on 27 relevant studies, meta-analyses demonstrated that any alcohol consumption (OR = 1.63, CI = 1.39–1.91), problematic drinking (OR = 1.69, CI = 1.45–1.97), and alcohol use in sexual contexts (OR = 1.98, CI = 1.63–2.39) were all found to be significantly associated with unprotected sex among PLWHA. Taken together, these results suggest that there is a significant link between PLWHA’s use of alcohol and their engagement in high-risk sexual behavior. These findings have implications for the development of interventions to reduce HIV transmission risk behavior in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite the implementation of a number of prevention-related programs aimed at reducing the spread of HIV, HIV incidence continues to remain at a high level throughout many parts of the world, with current estimates indicating 2.7 million new HIV infections in 2007 alone [1]. Fueling much of this ongoing HIV epidemic is the occurrence of unprotected sexual intercourse between HIV-infected and non-infected individuals. It has been reported that over 70% of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) remain sexually active after diagnosis [2], and that one-third of PLWHA engage in unprotected sexual behavior [3]. Some reports have even shown rates of unprotected sex among PLWHA to be as high as 84% [4]. Given the level of unprotected sex demonstrated by PLWHA, and recognizing that alcohol has not only been frequently implicated as a risk factor for unprotected sex, but also that heavy alcohol consumption tends to be more prevalent among PLWHA than among the general population [5, 6], the present investigation sought to statistically assess the association between alcohol consumption and unprotected sex in PLWHA populations through a meta-analysis.

Alcohol and Unprotected Sex: Theory and Research

Among the numerous factors that have been associated with unprotected sex (e.g., [2, 7]), alcohol has received particular attention. Alcohol has been purported to have a relatively direct impact on unprotected sex, serving as a disinhibitory mechanism [8], and resulting in “alcohol myopia [9],” in which a restricted cognitive capacity stemming from alcohol consumption causes one to focus only on impelling immediate cues (e.g., arousal) while ignoring inhibiting distant cues (e.g., risk of HIV or STI acquisition with potential consequences in the future) when making decisions about condom use (see also [10, 11]). Additionally, expectations about alcohol can be impactful on their own, affecting condom use attitudes and skills, risk perceptions, unsafe intentions, and risky sexual behavior [12–18]. Finally, “third variables” can also account for the alcohol-risky sex association [8, 19–21]. Having a “risky” personality type, or being high on the dimensions of sensation seeking [22–25] or sexual compulsivity (e.g., [26–29]) might dispose individuals to engage in both risky drinking and risky sex, and from a situational perspective, because alcohol is often consumed in the same venues where new and casual sexual partners are met, a link between alcohol use and unprotected sex may result from the sheer confluence of accessible alcohol and available sexual partners [8, 19].

Empirical Support for an Alcohol-Risky Sex Association

The association between alcohol and risky sex has been assessed with varying degrees of specificity, focusing on (1) global-level associations that examine the relationship between generalized measures of alcohol use and unprotected sex; (2) situational-level associations that examine the relationship between alcohol use in sexual contexts (e.g., alcohol before/during sex) and unprotected sex; and (3) event-level associations that examine the relationship between a specific sexual act (or set of acts) and alcohol use prior to each corresponding act [30]. Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses regarding these associations is quite mixed. Although there appears to be evidence for a link at the global-level [30–32], the evidence for a link at the situational level is less pronounced [21, 30, 31, 33]. The association appears to be diminished even further at the event-level, with reviews tending not to support an overall event-level relationship, but instead suggesting that the relationship may be qualified by the nature of the encounter [30, 31, 34, 35] or the amount of alcohol consumed [21]. Taken as a whole, findings tend to provide inconsistent evidence for an overall alcohol-risky sex association.

The Present Investigation

Among the many studies that have investigated the association between alcohol and unprotected sex, only a small proportion has examined this association in samples of PLWHA. Additionally, although systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the alcohol-risky sex association across diverse samples, including adolescents [36], men who have sex with men (MSM) [21], and African populations [19, 32], a comprehensive, macro-level assessment of the alcohol-risky sex association specifically among PLWHA remains absent from the literature. Given that (1) a significant portion of PLWHA continue to engage in unprotected sex [3]; (2) alcohol use and problematic drinking tend to be higher among PLWHA than among non-infected individuals [5, 6]; and (3) the evidence for a link between alcohol and unprotected sex is mixed, and for the most part based on HIV-negative samples; the present study involved a meta-analysis to statistically assess the extent to which alcohol is linked to unprotected sex in samples of PLWHA.

Method

Search Strategy and Study Selection

PsycInfo and Ovid Medline (including CINAH—Nursing and Allied Health) databases were queried for articles that tested associations between alcohol and unprotected sex in samples of PLWHA. Comprehensive search terms were employed for each factor under investigation. Search terms for PLWHA included “HIV,” “AIDS,” “human immunodeficiency virus,” “acquired immune deficiency syndrome,” “plh,” “pla,” “plha,” and “plwha.” For risky sex, terms included “std,” “sexually transmitted disease,” “safe*,” “sex*,” “unsafe*,” “risk*,” “condom,” “protect*,” “unprotect*,” “sexually transmitted infection,” and “sti.” Finally, for alcohol, terms included “alcohol,” “drink*,” “drinking,” and “substance use.”

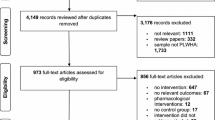

Figure 1 summarizes the search results that yielded 2,604 articles from Medline and 1,677 articles from PsycInfo. Titles and abstracts for all references were reviewed, and 247 articles were retained for full paper reviews. Articles were retained for further analysis if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) consisted of original, quantitative research published in a peer reviewed journal; (2) reported a statistical association between alcohol and risky sex; (3) statistically tested the alcohol-risky sex association for PLWHA alone (or separately from HIV-negative/HIV status unknown samples); and (4) assessed alcohol consumption independently from the use of other substances. In total, 36 publications satisfied the above search criteria. Two additional studies that met the inclusion criteria were found through an examination of the reference sections from relevant studies and through a listserv reporting on recent HIV-related publications, bringing the total to 38 studies.

All 38 studies were examined for unadjusted and adjusted associations between alcohol consumption and unprotected sex. Because data pertaining to adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were not available for over 80% of the studies (n = 31/38), a focus was placed on unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). ORs and CIs were taken directly from publications, and if not provided, were calculated based on available contingency tables. If neither ORs nor contingency tables were provided, attempts were made to contact authors to obtain relevant statistical information. Taken together, these procedures yielded ORs and CIs for 27 studies which formed the basis of our meta-analysis. Key study characteristics and outcomes for all 27 relevant publications can be found in Table 1.

Definition of Alcohol Consumption and Risky Sex Constructs

Measurement of alcohol consumption and risky sexual behavior was highly variable across studies (see Table 1). Alcohol consumption was frequently assessed using standardized measures for problematic consumption or abuse, including the AUDIT [37], the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) [38], and classifications of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [39]. In other instances, a variety of non-standardized items were used to assess frequency and patterns of alcohol consumption. Across studies, there was a tendency for analyses to be based on dichotomous consumption categories, comparing either any alcohol consumption with abstinence, or comparing “binge drinking,” “problem drinking,” “at-risk drinking,” “hazardous drinking,” or “dependence,” with moderate and no drinking.

In a subset of studies, alcohol consumption was examined specifically in the context of sexual activity, with assessments focusing on alcohol use that preceded sexual acts. Although single-item measures were typically used to assess overall alcohol use prior to sex over specified time periods (e.g., past 6 months), daily diary entries were also employed to assess event-specific alcohol consumption [40]. As with the global alcohol measures, there was a tendency for alcohol use in sexual contexts to be dichotomized, comparing those who consumed alcohol prior to sex versus those who did not.

For the present meta-analysis, measures of alcohol consumption from all 27 studies were classified into one of three categories. The first category involved any alcohol use; comparing PLWHA who did versus did not consume any amount of alcohol. The second category focused on “problematic drinking,” comparing PLWHA who engaged in “binge,” “at-risk,” “problem,” or “hazardous” drinking versus those who did not. The last category focused on alcohol use in sexual contexts, comparing PLWHA who had versus had not consumed alcohol prior to sex (see Table 1).

For risky sexual behavior, 26 out of 27 studies included an outcome that was based on engaging in sex without a condom, and in one study [41], the outcome focused on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (see Table 1). Despite the substantial degree of consistency in terms of studies’ focus on condom use, measurement varied based on sexual act, relationship type, and partner serostatus. However, condom use measures were dichotomized in essentially all cases, leading to outcomes based on PLWHA who did versus did not engage in unprotected sex. In the present meta-analysis, this method of classification was employed. For the one study with STIs as the outcome [41], because STIs are indicative of condom non-use, the absence versus the occurrence of STIs were classified in terms of not engaging versus engaging in unprotected sex, respectively, and data were analyzed accordingly.

Statistical Analysis

Three separate meta-analyses were performed to assess associations between unprotected sex and (1) any alcohol use (vs. no use); (2) problematic drinking (vs. no drinking/moderate drinking); and (3) alcohol use in sexual contexts (vs. no alcohol use in sexual contexts). Note that whereas the first two categories were aimed at assessing global-level associations, the third category assessed alcohol-risky sex associations at the situational- and event-levels [30].

Meta-analyses examined univariate ORs using DerSimonian and Laird’s [42] random effects model. For studies with multiple estimates for a given association (e.g., separate ORs for casual and steady partners), estimates were pooled prior to analysis (see Table 1 for details). Overall ORs and 95% CIs were based on weighted pooled measures. Forest plots were used to visually assess the individual and pooled OR and CI values, and heterogeneity was assessed using both the Cochrane Q-test and the I 2 statistic [43]. Publication bias was assessed using tests proposed by Begg and Mazumdar [44] and by Egger et al. [45]. Subgroup analyses were also performed when sufficient data were available. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata Version 10.1 [46].

Results

Of the 27 relevant studies, nine examined the association between drinking any alcohol and unprotected sex [27, 41, 47–53], 15 examined the association between problematic drinking and unprotected sex [47, 52–65], and nine examined the association between alcohol consumption in sexual contexts and unprotected sex [23, 40, 48, 49, 51, 66–69]. Six studies examined the association between alcohol and unprotected sex using more than one alcohol consumption category.

Primary Analyses

Random effect analyses revealed significant associations between the occurrence of unprotected sex and all three alcohol consumption categories. As seen in Fig. 2, PLWHA who consumed any amount of alcohol had a significantly increased likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex compared to PLWHA who did not consume any alcohol (pooled OR = 1.63, CI = 1.39–1.91). Similarly, PLWHA who engaged in problematic drinking demonstrated a significantly increased likelihood of unprotected sex compared to those who had not engaged in problematic drinking (pooled OR = 1.69, CI = 1.45–1.97) (see Fig. 3), and as shown in Fig. 4, there was a significantly increased likelihood of engaging in unprotected sex among PLWHA who drank alcohol in sexual contexts versus those who did not (pooled OR = 1.98, CI = 1.63–2.39).

Tests of heterogeneity and publication bias (see Fig. 5 for Begg’s funnel plots) demonstrated that for any alcohol consumption, heterogeneity (Q(8) = 6.26, p = 0.62; I 2 = 0%, CI = 0–65%) and publication bias (p = 1.00 and 0.87 by Begg and Mazumdar’s and Egger et al.’s tests, respectively) were not significant. These non-significant patterns were also evident for problematic drinking (heterogeneity: Q(14) = 6.88, p = 0.94; I 2 = 0%, CI = 0–54%; publication bias: p = 0.69 and 1.00 by Begg and Mazumdar’s and Egger et al.’s tests, respectively) and for alcohol consumption in sexual contexts (heterogeneity: Q(8) = 5.54, p = 0.70; I 2 = 0%, CI = 0–65%; publication bias: p = 0.35 and 0.84 by Begg and Mazumdar’s and Egger et al.’s tests, respectively).

Subgroup Analyses

Available data were not sufficient to perform subgroup analyses based on partner type (e.g., casual/steady partners) or risk category (e.g., MSM, Heterosexual). Sufficient data for subgroup analyses were available for a gender-based comparison, but only for problematic drinking, demonstrating the strongest association for male samples (n = 5 studies; pooled OR = 1.88, CI = 1.38–2.56), followed by combined male-female samples (n = 8 studies; pooled OR = 1.72, CI = 1.41–2.10), and female samples (n = 3 studies; pooled OR = 1.50, CI = 1.00–2.25).

Discussion

The present investigation involved a series of meta-analyses to statistically assess the association between alcohol and unprotected sex in samples of PLWHA. Results demonstrated that any alcohol consumption, problematic drinking, and alcohol use in sexual contexts, were all significantly associated with the occurrence of unprotected sex among PLWHA. These findings, which are based on relatively diverse indicators of alcohol consumption, and which involve global-, situational-, and event-level associations, provide consistent support for the involvement of alcohol in PLWHA’s engagement in unsafe sex.

Drinking any alcohol and engaging in problematic drinking were both associated with PLWHA’s sexual risk behavior, and taken together, these results demonstrated that PLWHA who drank were approximately 60–70% more likely to have engaged in unprotected sex than PLWHA who did not consume alcohol. Although these global-level associations cannot definitively establish a causal or even a temporal link between alcohol and risky sex [30], their statistical significance precludes one from ruling out entirely the possibility that such links may potentially exist. It is also possible that these significant global-level associations are indicative of underlying personality characteristics or situational factors that may in and of themselves be associated with both a tendency to consume alcohol and an inclination to engage in sex without condoms.

Interestingly, the overall effect sizes for any alcohol use and for problematic drinking were highly similar (OR = 1.63 and 1.69, respectively). Using this simple comparison as the basis for a very crude dose-response analysis, it appears that among PLWHA, consuming alcohol in larger quantities or with greater frequency may not necessarily be associated with a proportional increase in risk behavior. Rather, the alcohol-risky sex association at the global-level for PLWHA appears to be bifurcated based on abstinence from alcohol versus the consumption of alcohol at any level. Although this finding is somewhat contrary to data from Fisher et al. [19], unlike Fisher et al.’s meta-analysis, the present study focused solely on PLWHA, who have been shown to engage in higher levels of alcohol consumption and problematic drinking than non-infected individuals [5, 6]. With this increased incidence of heavy alcohol consumption, a relatively larger proportion of PLWHA who consume alcohol may be classified as “problematic drinkers,” and this may therefore have led to a situation in the present meta-analysis in which there would have been considerable overlap between those in the “any drinking” category and those in the “problematic drinking” category. Alternatively, due to factors such as HIV treatment-related issues and co-morbidities, PLWHA might be susceptible to the effects of alcohol at lower levels of consumption compared to non-infected individuals [70]. Therefore, because alcohol intoxication may occur for some PLWHA after consuming even relatively small amounts of alcohol, a meaningful difference in alcohol-risky sex associations demonstrated by PLWHA who consume alcohol at lower levels versus PLWHA who consume alcohol at higher levels may be difficult to discern. Although these explanations may account for the similarity in effect sizes found in the present investigation, additional research is necessary to more empirically assess the possibility of a dose-response relationship.

The relationship between alcohol use in sexual contexts and unprotected sex, which addressed both situational- and event-level associations, was also found to be significant. PLWHA who reported drinking in sexual contexts were almost twice as likely to engage in unprotected sex compared to those who did not drink in such contexts. Although still not capable of providing evidence for a causal relationship between alcohol and unprotected sex, this significant association offers support for a temporal link. This link is further bolstered by our inclusion of two studies that assessed event-level associations in PLWHA samples [23, 40], one of which yielded significant outcomes through daily diary measurements [40].Footnote 1

This significant result appears to run contrary to findings from previous work involving HIV-negative populations, which tend not to provide overall support for situational- and event-level associations [21, 30, 31, 34, 35], suggesting the possibility that this association differs based on HIV serostatus. This difference may in part be due to the disparity in condom-related motivations experienced by PLWHA versus HIV-negative individuals. For PLWHA, the motivation to use condoms may derive from social or cultural norms that stress the need to prevent the transmission of HIV to one’s partner, whereas for non-infected individuals, the motivation might be based on a desire to protect oneself from possible HIV infection [23, 35, 72, 73]. Although the suppressive effect of the former motivation may be stronger than that of the latter motivation when sober, under conditions of intoxication, alcohol myopia [9] may equally suppress these motivations, and the resultant increase in risk behavior would therefore be larger for PLWHA than for HIV-negative individuals. Alternatively, the difference may stem from issues of disclosure that are unique to PLWHA, whereby alcohol may impact PLWHA’s ability or motivation to disclose their HIV status to their partners, which in turn could result in condom non-use [23]. Alcohol may therefore provide an escape from these powerful constraints that typically govern PLWHA’s condom use decisions.

Limitations

Results from the present meta-analysis should be viewed in terms of possible limitations. First, most studies involved US samples, and given existing cultural differences in stigma, norms, and alcohol use, it may be difficult to generalize the current findings to other populations. Second, virtually all studies relied on self-reports of alcohol and risky sex. Because individuals may use alcohol as an excuse to justify unprotected sex after the fact, the strength of the alcohol-risky sex associations deriving from self-reports may have been overestimated. Third, very few studies examined partners’ alcohol consumption. Condom use decisions may be based on one or both partners, and in some cases, these decisions may be more affected by the intoxication of one partner versus the other [32]. Fourth, all studies involved correlational designs, thus making it impossible to draw causal conclusions from the present results. Fifth, because usable and complete AOR and corresponding CI data were available only for seven studies, it was necessary to base meta-analyses on unadjusted ORs rather than on AORs. Among the 20 studies without usable AOR data, AORs were not available for the following reasons: (1) in six studies, AORs were not calculated as a result of alcohol failing to reach significance in unadjusted analyses; (2) in four studies, AORs were not reported as a result of alcohol failing to reach significance in multivariable analyses; (3) in seven studies, only partial AOR and CI data were available, and this included AORs being presented only for groups yielding significant unadjusted effects (e.g., casual but not steady partners), as well as CI values not being reported; and (4) in three studies, there was no indication that any adjusted analyses (either with or without alcohol) had been performed. Even when complete AOR and CI data were available, the number of AORs available for each specific alcohol consumption category (any alcohol use = 2; problematic drinking = 4; alcohol use in sexual contexts = 2) was not sufficient to reliably perform meta-analytic procedures. Furthermore, a qualitative review of the studies with available AOR data did not appear to reveal any factor groupings (e.g., demographic, behavioral, etc.) that could potentially account for significant versus non-significant multivariable results. Taking this into account, our results, which are derived from unadjusted associations, potentially misestimate the strength of the alcohol-risky sex relationship and do not adequately take into account the influence of possible mediating factors. Sixth, alcohol and unprotected sex variables in the meta-analysis were constructed on the basis of diverse sets of measures (see Table 1). Employing better specified classifications for both variables could have perhaps led to more accurate representations of the alcohol-risky sex relationship. Seventh, given the nature of the available data, our comparison groups for all three alcohol consumption categories included PLWHA who had not consumed alcohol. Because factors such as poor health may be associated with abstinence from both alcohol and sexual behavior [74], it is possible that including those who did not drink alcohol in the comparison groups could have artificially inflated our alcohol-risky sex effect sizes. Although it would have been beneficial to conduct additional analyses that excluded non-drinkers and instead specifically compared the risk behavior of PLWHA who consumed alcohol at moderate levels versus PLWHA who consumed alcohol at hazardous levels, only two of 15 studies within the problematic drinking category contained the details necessary to make this comparison, and meta-analytic procedures using this classification were therefore not possible. More accurate estimates of the alcohol-risky sex relationship among PLWHA could potentially be determined through additional research that examines the role of alcohol in a more clearly-defined dose-response manner.

Summary and Conclusions

The present investigation is to our knowledge the first meta-analytic review that has assessed the association between alcohol use and unprotected sex specifically among PLWHA. Our significant findings provide support for an overall association between PLWHA’s alcohol consumption and their engagement in high-risk sexual behavior, and in particular, the significant effect demonstrated for alcohol use in the context of sexual activity is further suggestive of alcohol’s possible role in PLWHA’s condom use decisions. However, given the limitations discussed above, we cannot make unequivocal claims regarding the independent role of alcohol in PLWHA’s risky sex decisions, primarily because the present findings cannot rule out the possible impact of third variables that may mediate the alcohol-risky sex association. It is therefore essential that future research more directly addresses the role of these third variables, and through such investigations, a clearer picture of the relationships among alcohol use, personality characteristics, health-related factors, situational factors, and unprotected sex can be determined.

Taking all of this into account, regardless of whether alcohol itself is independently related to PLWHA’s unsafe behavior, or whether alcohol is a marker for underlying factors that lead PLWHA to engage in unprotected sex, prevention efforts aimed at PLWHA could significantly benefit by addressing alcohol-related issues. From one perspective, HIV prevention interventions could include modules aimed at informing PLWHA about the effects of alcohol, as well as providing them with the necessary skills to use condoms when intoxicated. In fact, a recent South African investigation found some support for an intervention that included both risky sex and alcohol components [75]. From another perspective, interventions could be targeted specifically toward PLWHA who report alcohol use, particularly within sexual contexts. By focusing on this subgroup of PLWHA, prevention efforts may have their greatest impact. Based on both of these perspectives, recognizing the association between alcohol and unprotected sex among PLWHA could assist in both the tailoring and targeting of prevention-related interventions. Such interventions could significantly impact PLWHA’s levels of sexual risk behavior, potentially leading to decreases in HIV transmission over time.

Notes

In addition to the event-level investigation by Kiene et al. [40], a study by Barta et al. [71] employed telephone-based daily diary assessments and found a significant event-level association between PLWHA’s alcohol consumption prior to sex and the occurrence of unprotected sexual intercourse. Problematic drinking (i.e., alcohol dependence) was negatively related to unprotected sex. Due to the nature of the data analytic procedures and statistical outcomes presented by Barta et al. results from the study were not included in our meta-analyses.

References

UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS 2008.

Crepaz N, Marks G. Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: a review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS. 2002;16(2):135–49.

Kalichman SC. HIV transmission risk behaviors of men and women living with HIV-AIDS: prevalence, predictors, and emerging clinical interventions. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2000;7:32–47.

Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Intentional unsafe sex (barebacking) among HIV-positive gay men who seek sexual partners on the internet. AIDS Care. 2003;15(3):367–78.

Cook RL, Sereika SM, Hunt SC, Woodward WC, Erlen JA, Conigliaro J. Problem drinking and medication adherence among persons with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(2):83–8.

Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV cost and services utilization study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(2):179–86.

Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1581–6.

Dingle GA, Oei TP. Is alcohol a cofactor of HIV and AIDS? Evidence from immunological and behavioral studies. Psychol Bull. 1997;122(1):56–71.

Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45(8):921–33.

MacDonald TK, MacDonald G, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Alcohol, sexual arousal, and intentions to use condoms in young men: applying alcohol myopia theory to risky sexual behavior. Health Psychol. 2000;19(3):290–8.

MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Martineau AM. Alcohol myopia and condom use: can alcohol intoxication be associated with more prudent behavior? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(4):605–19.

Bryan A, Ray LA, Cooper ML. Alcohol use and protective sexual behaviors among high-risk adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(3):327–35.

Crowe LC, George WH. Alcohol and human sexuality: review and integration. Psychol Bull. 1989;105(3):374–86.

George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:92–124.

Gordon CM, Carey MP, Carey KB. Effects of a drinking event on behavioral skills and condom attitudes in men: implications for HIV risk from a controlled experiment. Health Psychol. 1997;16(5):490–5.

LaBrie J, Earleywine M, Schiffman J, Pedersen E, Marriot C. Effects of alcohol, expectancies, and partner type on condom use in college males: event-level analyses. J Sex Res. 2005;42(3):259–66.

Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM. The effects of alcohol and expectancies on risk perception and behavioral skills relevant to safer sex among heterosexual young adult women. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(4):476–85.

Murphy ST, Monahan J, Miller LC. Inference under the influence: the impact of alcohol and inhibition conflict on women’s sexual decision making. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1998;24(5):517–28.

Fisher JC, Bang H, Kapiga SH. The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34(11):856–63.

Stall R, Leigh B. Understanding the relationship between drug or alcohol use and high risk sexual activity for HIV transmission: where do we go from here? Addiction. 1994;89(2):131–4.

Woolf SE, Maisto SA. Alcohol use and risk of HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9354-0.

Kalichman SC, Heckman T, Kelly JA. Sensation seeking as an explanation for the association between substance use and HIV-related risky sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25(2):141–54.

Kalichman SC, Weinhardt L, DiFonzo K, Austin J, Luke W. Sensation seeking and alcohol use as markers of sexual transmission risk behavior in HIV-positive men. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(3):229–35.

Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1994.

Kalichman SC, Johnson JR, Adair V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, Kelly JA. Sexual sensation seeking: scale development and predicting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. J Pers Assess. 1994;62(3):385–97.

Benotsch EG, Kalichman SC, Kelly JA. Sexual compulsivity and substance use in HIV-seropositive men who have sex with men: prevalence and predictors of high-risk behaviors. Addict Behav. 1999;24(6):857–68.

Benotsch EG, Kalichman SC, Pinkerton SD. Sexual compulsivity in HIV-positive men and women: prevalence, predictors, and consequences of high-risk behaviors. Sex Addict Compuls. 2001;8(2):83–99.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: reliability, validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. J Pers Assess. 1995;65(3):586–601.

Kalichman SC, Cain D. The relationship between indicators of sexual compulsivity and high risk sexual practices among men and women receiving services from a sexually transmitted infection clinic. J Sex Res. 2004;41(3):235–41.

Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use, risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. Am Psychol. 1993;48(10):1035–45.

Halpern-Felsher BL, Millstein SG, Ellen JM. Relationship of alcohol use and risky sexual behavior: a review and analysis of findings. J Adolesc Health. 1996;19(5):331–6.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8(2):141–51.

Leigh BC, Morrison DM, Hoppe MJ, Beadnell B, Gillmore MR. Retrospective assessment of the association between drinking and condom use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(5):773–6.

Leigh BC. Alcohol and condom use: a meta-analysis of event-level studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29(8):476–82.

Weinhardt LS, Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:125–57.

Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):101–17.

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

McLellan A, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf. Updated 2005. Accessed 8 Feb 2009.

Kiene SM, Simbayi LC, Abrams A, Cloete A, Tennen H, Fisher JD. High rates of unprotected sex occurring among HIV-positive individuals in a daily diary study in South Africa: the role of alcohol use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(2):219–26.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Sexually transmitted infections among HIV seropositive men and women. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76(5):350–4.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–101.

Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Stata for Windows [computer program]. Version 10.1. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2008.

Stein M, Herman DS, Trisvan E, Pirraglia P, Engler P, Anderson BJ. Alcohol use and sexual risk behavior among human immunodeficiency virus-positive persons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(5):837–43.

Purcell DW, Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Mizuno Y, Woods WJ. Substance use and sexual transmission risk behavior of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(1–2):185–200.

Purcell DW, Moss S, Remien RH, Woods WJ, Parsons JT. Illicit substance use, sexual risk, and HIV-positive gay and bisexual men: differences by serostatus of casual partners. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 1):S37–47.

Morin SF, Steward WT, Charlebois ED, et al. Predicting HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: findings from the healthy living project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(2):226–35.

Kalichman SC. Psychological and social correlates of high-risk sexual behaviour among men and women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 1999;11(4):415–27.

Ehrenstein V, Horton NJ, Samet JH. Inconsistent condom use among HIV-infected patients with alcohol problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73(2):159–66.

Chuang CH, Liebschutz JM, Horton NJ, Samet JH. Association of violence victimization with inconsistent condom use in HIV-infected persons. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(2):201–7.

Bouhnik AD, Preau M, Lert F, et al. Unsafe sex in regular partnerships among heterosexual persons living with HIV: evidence from a large representative sample of individuals attending outpatients services in France. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S57–62.

Bouhnik AD, Preau M, Schiltz MA, et al. Unprotected sex in regular partnerships among homosexual men living with HIV: a comparison between sero-nonconcordant and seroconcordant couples. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S43–8.

Brewer TH, Zhao W, Metsch LR, Coltes A, Zenilman J. High-risk behaviors in women who use crack: knowledge of HIV serostatus and risk behavior. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(7):533–9.

Cook RL, McGinnis KA, Kraemer KL, et al. Intoxication before intercourse and risky sexual behavior in male veterans with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Med Care. 2006;44(8 Suppl 2):S31–6.

Darrow WW, Webster RD, Kurtz SP, Buckley AK, Patel KI, Stempel RR. Impact of HIV counseling and testing on HIV-infected men who have sex with men: the south beach health survey. AIDS Behav. 1998;2(2):115–26.

Krupitsky EM, Horton NJ, Williams EC, et al. Alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors among HIV-infected hospitalized patients in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(2):251–6.

Milam J, Richardson JL, Espinoza L, Stoyanoff S. Correlates of unprotected sex among adult heterosexual men living with HIV. J Urban Health. 2006;83(4):669–81.

Moatti JP, Prudhomme J, Traore DC, et al. Access to antiretroviral treatment and sexual behaviours of HIV-infected patients aware of their serostatus in Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS. 2003;17(Suppl 3):S69–77.

Olley BO, Seedat S, Gxamza F, Reuter H, Stein DJ. Determinants of unprotected sex among HIV-positive patients in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2005;17(1):1–9.

Palepu A, Raj A, Horton NJ, Tibbetts N, Meli S, Samet JH. Substance abuse treatment and risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons with alcohol problems. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(1):3–9.

Theall KP, Clark RA, Powell A, Smith H, Kissinger P. Alcohol consumption, ART usage and high-risk sex among women infected with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):205–15.

Tucker JS, Kanouse DE, Miu A, Koegel P, Sullivan G. HIV risk behaviors and their correlates among HIV-positive adults with serious mental illness. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(1):29–40.

Reilly T, Woo G. Predictors of high-risk sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2001;5(3):205–17.

Niklowitz M, Eich-Hochli D. Is there a correlation between alcohol drinking and sexual risk taking? A discussion of conceptional aspects exemplified by HIV infected men with homosexual behavior [in German]. Soz Praventivmed. 1997;42(5):286–97.

Kiene SM, Christie S, Cornman DH, et al. Sexual risk behaviour among HIV-positive individuals in clinical care in urban KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS. 2006;20(13):1781–4.

Godin G, Savard J, Kok G, Fortin C, Boyer R. HIV seropositive gay men: understanding adoption of safe sexual practices. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8(6):529–45.

Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, McGinnis KA, Maisto SA, Bryant K, Justice AC. Adjusting alcohol quantity for mean consumption and intoxication threshold improves prediction of nonadherence in HIV patients and HIV-negative controls. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(9):1645–51.

Barta WD, Portnoy DB, Kiene SM, Tennen H, Abu-Hasaballah KS, Ferrer R. A daily process investigation of alcohol-involved sexual risk behavior among economically disadvantaged problem drinkers living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:729–40.

Parsons JT, Vicioso K, Kutnick A, Punzalan JC, Halkitis PN, Velasquez MM. Alcohol use and stigmatized sexual practices of HIV seropositive gay and bisexual men. Addict Behav. 2004;29(5):1045–51.

Parsons JT, Vicioso KJ, Punzalan JC, Halkitis PN, Kutnick A, Velasquez MM. The impact of alcohol use on the sexual scripts of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Sex Res. 2004;41(2):160–72.

Bogart LM, Collins RL, Kanouse DE, et al. Patterns and correlates of deliberate abstinence among men and women with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1078–84.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, et al. Randomized trial of a community-based alcohol-related HIV risk-reduction intervention for men and women in Cape Town South Africa. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(3):270–9.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the South African Medical Research Council (MRC) through a grant received from the US President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. We would also like to thank Dr. Charles Parry at the MRC for his comments on this manuscript, and we are grateful to delegates of the MRC/CDC Alcohol and Infectious Diseases Technical Meeting (July 2008, Cape Town, South Africa) for their feedback regarding this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shuper, P.A., Joharchi, N., Irving, H. et al. Alcohol as a Correlate of Unprotected Sexual Behavior Among People Living with HIV/AIDS: Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Behav 13, 1021–1036 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z