Abstract

This paper examines HIV risk behavior among HIV-uninfected adults living with people taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Uganda. A prospective cohort of 455 HIV-uninfected non-spousal household members of ART patients receiving home-based AIDS care was enrolled. Sexual behavior, HIV risk perceptions, AIDS-related anxiety, and the perception that AIDS is curable were assessed at baseline, 6, 12 and 24 months. Generalized linear mixture models were used to model risk behavior over time and to identify behavioral correlates. Overall, risky sex decreased from 29% at baseline to 15% at 24-months. Among women, risky sex decreased from 31% at baseline to 10% at 6 months and 15% at 24 months. Among men, risky sex decreased from 30% at baseline to 8% at 6 months and 13% at 24 months. Perceiving HIV/AIDS as curable and lower AIDS-related anxiety were independently associated with risky sex. No evidence of behavioral disinhibition was observed. Concerns regarding behavioral disinhibition should not slow down efforts to increase ART access in Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With increasing access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) globally (UNAIDS and World Health Organization 2005), there is concern that HIV-uninfected individuals may increase risky sexual behavior because they perceive HIV to be a treatable disease (Abbas et al. 2006; Baggaley et al. 2006; Cassell et al. 2006; Kennedy et al. 2007). Sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for more than 70% of all HIV infections worldwide, is currently the major focus of efforts to expand ART (Liden et al. 2005). However, the association between availability of ART and the sexual behavior of HIV-uninfected individuals on the continent is not yet known.

Studies among men who have sex with men (MSM) in industrialized countries indicate that increased sexual risk-taking may be related to perceptions of decreased risk coupled with perceived high effectiveness of ART and perceived lowered severity of HIV (Huebner et al. 2004; International Collaboration on HIV Optimism 2003; Ostrow et al. 2002; Stolte et al. 2004). Such perceptions might serve to justify continued or relapse of HIV risk-behaviors as has been observed in some studies in the US and Europe (Elford et al. 2002; Kelly et al. 1998; Osmond et al. 2007). The construction of HIV/AIDS knowledge and risk models is often dependent upon not only on what people know about the virus, but also on what they believe they know (Smith 2003; Vanable et al. 2000). Beliefs are sometimes inconsistent with accepted facts and can be based on a rationale framed by perceptions derived from personal and socio-cultural belief systems (Kalichman et al. 1998; Lin et al. 2005).

Several studies have concentrated on evaluating sexual risk behavior among individuals on ART (Bunnell et al. 2006; Crepaz et al. 2004; Dukers et al. 2001; Moatti et al. 2003). Information regarding the association between ART-related perceptions and risk behavior among the larger population of HIV-uninfected individuals is limited. In Uganda, a country where both sexual risk behavior and HIV prevalence has declined (Mbulaiteye et al. 2002; Stoneburner and Low-Beer 2004), modeling studies have suggested that the current gains in prevention could be threatened by increased risk behavior associated with widespread use of ART (Gray et al. 2003). HIV-uninfected household members of infected individuals on ART may be at high risk for sexual disinhibition because of the profound improvements in health they directly observe. In this paper, we evaluate sexual risk behavior over 2 years of follow-up for HIV-uninfected non-spousal adult household members of ART patients in rural Uganda. Additionally, we examine the relationship between perceived risk of HIV infection, AIDS-related anxiety, and the perception of HIV as a curable disease and reported high-risk sexual behavior in this population.

Methods

Study Setting

Beginning in May 2003, we provided home-based ART to clinically eligible HIV-infected clients of the Tororo branch of The AIDS Support Organization (TASO), an indigenous HIV care non-governmental organization in Uganda. These patients were enrolled in the Home-Based AIDS Care (HBAC) study, a three-arm, 3-year randomized controlled trial that evaluated different methods of monitoring ART adherence (Weidle et al. 2006). All ART patients received the same behavioral interventions (i.e. group education, personal adherence and risk reduction plans developed with trained counselors, a medicine companion, and weekly home delivery of ART by trained lay field officers). In addition, HIV-uninfected household members were also enrolled and followed-up at 6, 12, and 24 months post-enrollment. We defined a household as consisting of persons who shared food cooked at a common hearth and slept in the same house or cluster of houses for at least 5 days of a week for the preceding 3 months. We offered household members home-based VCT at baseline and at annual follow-up visits and provided basic medical treatment, including treatment for malaria, diarrhea, and tuberculosis through the study clinic at Tororo District Hospital. Details of the VCT intervention are described elsewhere (Were et al. 2006).

Study Design

In this analysis, we examine the sexual risk behavior of HIV-uninfected household members of ART patients as a prospective cohort study. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from each participant in English or one of the six local languages.

Study Subjects

Participants in this analysis were non-spousal household members of ART-naïve adults who initiated ART in the HBAC study, were 18–69 years old, and HIV seronegative at baseline VCT. We excluded HIV-uninfected household members who were spouses of ART patients since they participated in more extensive risk reduction interventions than did other household members.

Measurements

At enrollment and at 6, 12, and 24 months, study counselors conducted private structured interviews with household members in their homes. Interviewers and participants were matched by ethnic background. Face-to-face interviews included questions regarding participant demographics, desire for children, beliefs and perceptions about one’s personal risk of HIV infection and sexual risk behavior. Interviewers made three visits to try to locate household members before being declared unavailable. We excluded participants from further follow-up at the point of death of the household member receiving ART because members of these households might no longer be comparable to members of households where ART patients had not died.

Our primary predictor variables were standard demographic variables and participants’ perceptions and attitudes about HIV and AIDS. Demographic variables collected at baseline included sex, age, religion, main source of income, education, relationship to the household ART patient and marital status. Income was categorized as “trade” for all forms of activity that created income, “salary” for wage and salaried employment, “farming” for agricultural farming and “dependent” for those who reported receiving money from others as their main source of income. As a measure of AIDS-related anxiety, we asked participants whether they felt worried about getting HIV and about having HIV/AIDS (1 = hardly worried, 2 = a little bit worried, 3 = worried, 4 = extremely worried). For multivariate analyses, these two questions were combined into a single dichotomous variable: worried (3 or 4 for both questions) and lower degree of worry. Clients were also asked whether they perceived HIV/AIDS to be curable, whether people taking ART can transmit HIV if they have sex without a condom, and the likelihood of someone with HIV passing it on to them through sex.

Our primary outcome variable was risky sexual behavior. Using a matrix, we asked participants about their sexual activity including number and type of sexual partners, partner HIV status and behaviors with each partner including frequency of sex and condom use for the previous 3 months. We obtained partner-specific frequency of condom use for the previous 3 months as “always”, “sometimes”, or “never.” Participants provided each sexual partner’s HIV serostatus (tested positive, negative, unknown) and type of partner (spouse, steady, or casual partner). A casual partner was someone the participant had met once or very infrequently, a steady partner was someone that the participant had sex with regularly over an extended period. We defined risky sex as intercourse with inconsistent condom use with an HIV-infected partner or a partner of unknown serostatus during the prior 3 months.

Interventions

At enrollment and annually, we offered home-based VCT to adult household members of adults receiving ART. Prior to the baseline VCT, all adult household members received a group education session focused on HIV prevention and care, including ART. We provided follow-up VCT using a team of study counselors separate from those who administered survey modules. All counselors underwent extensive training and were proficient in at least one of the six local languages.

Statistical Methods

We double-entered questionnaire data using Epi-Info 2002 for windows version 3 (CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA) and conducted analyses using SAS/STAT® software version 9.1.3 Service Pack 3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA). We compared baseline demographic and socio-behavioral characteristics between men and women using the Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. We examined potential predictors of risky sexual behavior using bivariate analyses. To evaluate the potential for attrition bias related to the death of the index household member on the observed trends of HIV risk behavior over time, we employed a generalized linear mixture model (Fitzmaurice and Laird 2000). This model was based on a marginal regression model using generalized estimating equations (Zeger et al. 1988) to model sexual risk behavior, and a pattern mixture model to model non-ignorable drop-outs (Little 1995). A binary indicator variable was created to identify participants who were not followed-up due to the death of the household ART patient. Perceived risk of HIV infection, AIDS-related anxiety and perceiving HIV as curable were modeled as time-varying variables. We adjusted all models for age, gender, education, income, desire for children, relationship to the household ART patient and randomization arm of the index participant. Only statistically significant (P < 0.05) variables from the bivariate analysis were included in the final model.

Results

The 987 adult participants in HBAC who began ART had 455 HIV-uninfected non-spousal adult household members who enrolled at baseline (Table 1). Of these 455 household members, we excluded 60 (13%) at 6 months, 44 (10%) at 12 months and 8 (2%) at 24 months from behavioral follow-up because of the death of the household member on ART. One (<1%) household member died prior to the 6-month follow-up. Thirty-nine (8%) at 12 months and 12 (3%) at 24 months could not be traced as they had moved to locations outside study area, 21 (5%) declined follow-up participation at the 24-month follow-up. Those who were lost to follow-up did not differ from those who had completed follow-up with regard to baseline demographic and risk perception variables (Table 1) or risky sex at baseline (data not shown). Of the original 455 household members, 273 (60%) were women and 237 (52%) were married or co-habiting with their partner. The median age at enrollment was 40 years (interquartile range [IQR], 22–55 years) for women and 24 years (IQR, 20–40 years) for men. Of 455 HIV-uninfected household members, 38% were adult children of ART patients, 31% siblings, 10% parents, and 21% other relatives living in the same household. Two hundred twenty-three (49%) HIV-uninfected household members reported a desire for children at baseline; the proportion decreased gradually over the follow-up period, to 30% at 24 months (chi-square for trend 32.3, P < 0.0001). Only 26% of participants had education beyond primary school.

Of all HIV-uninfected adults at baseline, 36% reported lower AIDS-related anxiety; 4% stated that people on ART could not transmit HIV if they had sex without a condom; and 4% did not perceive themselves to be at risk of acquiring HIV (Table 1). There were no significant differences in these variables either between baseline and subsequent follow-up visits or between men and women (P > 0.05). The proportion of participants who reported lower AIDS-related anxiety decreased to 23% after 6 months and 26% at 12 months, but subsequently increased to 36% at 24 months. Belief that AIDS is curable decreased from 8% at baseline to 4% after 6 months, 3% at 12 months, and 1% at 24 months (chi-square for trend 20.0, P < 0.0001).

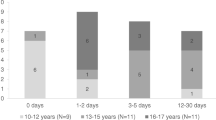

Fifty-two percent of participants reported at baseline that they had had sexual intercourse in the past 3 months. Men were more likely to be sexually active than women (60% of men vs. 47% of women, P < 0.001). Of the 236 sexually active participants, 73 (31%) had had risky sex in the past 3 months; the proportion among men and women was the same. During follow-up, the proportion of uninfected adult household members who reported having had risky sex in the prior 3 months was: 15 (9%) of 165 (8% of men vs. 10% of women) at 6 months, 21 (16%) of 132 (20% of men vs. 12% of women) at 12 months, and 15 (14%) of 105 (13% of men vs. 15% of women) at 24 months (Fig. 1). There was not a significant visit × gender interaction effect, indicating that risky sex did not vary by gender over time (P > 0.15).

The likelihood of reporting risky sex over time was not associated with any demographic characteristic (Table 2). When perceived risk related covariates were included in the model, perception of HIV risk and perceiving that people receiving ART could not transmit HIV if they had sex without a condom were not related to risky sex. However, perceiving HIV/AIDS as a curable disease (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.52, 95% confidence intervals [CI] 1.02–2.92, P < 0.05) and lower AIDS-related anxiety (AOR 0.43, 95% CI 0.22–0.76, P < 0.01) were independently associated with risky sex. There were no significant differences in risk behavior by randomization arm.

Of the 455 HIV-uninfected adult non-spousal household members at enrollment, six (four women and two men) experienced HIV-antibody seroconversion by the 24-month follow-up visit. Their median age was 36 years, four were siblings of an ART patient in the household, and none had education beyond primary school. At enrollment through to seroconversion, five participants reported being in polygamous marriages, four with spouses of unknown HIV status. The sixth had been previously married, widowed and separated. Prior to seroconversion, five consistently reported never having used a condom, and three of these consistently reported lower AIDS-related anxiety.

Discussion

We found that sexual risk behavior did not increase beyond that reported at baseline when ART was provided with concurrent VCT and HIV prevention counseling among HIV-uninfected adult household members of ART patients in rural Uganda. The group may have been at high risk of sexual disinhibition due to ART optimism derived from observing the positive impact of ART on the household index participant. This observation would suggest that widespread availability of ART may not lead to increased sexual risk behavior among HIV-uninfected persons in rural African settings (Crepaz et al. 2004; Gray et al. 2003) who are provided with VCT and HIV prevention counseling. Among participants, irrespective of age, risky sex initially decreased and thereafter remained steady among women and men, but did not exceed baseline levels at any point during the 2-year follow-up. These findings are consistent with those of Bunnell et al (2006, 2008) and provide initial evidence that within the context of regular counseling, provision of VCT and prevention education, gains arising out of the preventive effects of home-based ART are unlikely to be offset by sexual disinhibition.

Consistent with data from HIV-uninfected MSM populations in the US and Europe (Huebner et al. 2004; International Collaboration on HIV Optimism 2003; Vanable et al. 2000), we found that risky sex was associated with feeling that AIDS is a curable disease and a lower AIDS-related anxiety. However, at no time during the follow-up did the prevalence of risky sex in the prior 3 months exceed that at baseline. This suggests that, while these variables did predict risky sex, they were uncommon in the study group. There are no data available on the prevalence of these perceptions in the general population. Although, we didn’t specifically evaluate the added value of VCT and HIV prevention counseling offered to the participants, they are likely to be beneficial and may be suggestive of a need for continued counseling emphasizing that being on ART is not easy, that there are still many side effects and one’s quality of life is still diminished despite the fact they live longer, and that uninfected household members of ART patients should maintain lower risk behavior.

Studies with HIV-uninfected MSM in industrialized countries report conflicting evidence about the association of ART availability and HIV risk behavior (Elford et al. 2002; Huebner et al. 2004; International Collaboration on HIV Optimism 2003; Kalichman et al. 1998; Ostrow et al. 2002; Van et al. 1999. Some have demonstrated that treatment optimism is associated with risky sexual behaviors (Huebner et al. 2004; Ostrow et al. 2002). In contrast, a multi-site study conducted between January and December 2000 by the International Collaboration on HIV Optimism showed significantly lower rates of risky sex among HIV-uninfected MSM (International Collaboration on HIV Optimism 2003). Also, the overall reported decrease in risky sex among HIV-uninfected individuals in our study approximates the observed reductions in risk behavior reported in a recent systematic review evaluating the interplay of the availability of ART and HIV risk behavior in developing countries (Kennedy et al. 2007). Moreover, integrated ART and prevention programs have been associated with significant decreases in HIV transmission risk among ART patients living in these households (Bunnell et al. 2006; Bunnell et al. 2008).

Our study had a number of limitations. First, home-based VCT was offered as part of the intervention and the participants were indirectly exposed to the enhanced risk reduction counseling received by the ART patients and their uninfected spouses in the household; this may have influenced the reported sexual behavior, perhaps limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, our findings are based on self-reported sexual behavior, which has been shown to be biased in some settings (Schroder et al. 2003). Third, study counselors who provided baseline VCT also interviewed participants to collect sexual behavior information. This may have led to under-reporting of risky sex by participants due to social desirability. However, counselors were trained to minimize bias by using non-judgmental approaches, and the two men and four women who seroconverted during the course of the study reported inconsistent condom use and multiple partners, providing evidence that self-report may be reliable in this population. Fourth, we decided a-priori to discontinue follow-up for participants whose household member on ART died or relocated. We believe that these events would have constituted an additional and profound intervention effect and may have led to systematic bias. Additionally, a proportion of participants left the study catchment area to get married, trade or seek employment in other areas. However, we did not experience differential loss-to-follow-up with respect to the demographic variables, risk perception, AIDS-related anxiety or HIV sexual risk behavior. Moreover, one might speculate that those who were dropped from follow-up due to the death of the ART patient in the household might decrease their risk behavior, at least for some duration, because of their observations of their family member’s suffering and eventual death. However, the pattern mixture model revealed no systematic attrition bias.

This study provides data on HIV sexual risk behavior among HIV-uninfected adults who have directly observed the medical benefits of ART within their households. Small changes in population-level risk behavior indirectly associated with ART are likely to be more important determinants of the epidemic’s course than are changes among those receiving treatment (Crepaz et al. 2004). While sexual disinhibition may still occur among HIV-uninfected individuals in other settings where the levels of counseling and VCT that we provided in our study are not available, these data may alleviate some of the concerns about the potential for sexual disinhibition in an era of ART expansion, albeit in a study environment.

References

Abbas, U. L., Anderson, R. M., & Mellors, J. W. (2006). Potential impact of antiretroviral therapy on HIV-1 transmission and AIDS mortality in resource-limited settings. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 41, 632–641. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000194234.31078.bf.

Baggaley, R. F., Garnett, G. P., & Ferguson, N. M. (2006). Modelling the impact of antiretroviral use in resource-poor settings. PLoS Medicine, 3, e124. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030124.

Bunnell, R., Ekwaru, J. P., King, R., Bechange, S., Moore, D., Khana, K., et al. (2008). 3-Year follow-up of sexual behavior and HIV transmission risk of persons taking ART in Rural Uganda. Paper presented at the 15th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA, February.

Bunnell, R., Ekwaru, J. P., Solberg, P., Wamai, N., Bikaako-Kajura, W., Were, W., et al. (2006). Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS (London, England), 20, 85–92. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28.

Cassell, M. M., Halperin, D. T., Shelton, J. D., & Stanton, D. (2006). Risk compensation: The Achilles’ heel of innovations in HIV prevention? BMJ (Clinical Research Edition), 332, 605–607. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7541.605.

Crepaz, N., Hart, T. A., & Marks, G. (2004). Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: A meta-analytic review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 292, 224–236. doi:10.1001/jama.292.2.224.

Dukers, N. H., Goudsmit, J., de Wit, J. B., Prins, M., Weverling, G. J., & Coutinho, R. A. (2001). Sexual risk behaviour relates to the virological and immunological improvements during highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. AIDS (London, England), 15, 369–378. doi:10.1097/00002030-200102160-00010.

Elford, J., Bolding, G., & Sherr, L. (2002). High-risk sexual behaviour increases among London gay men between 1998 and 2001: What is the role of HIV optimism? AIDS (London, England), 16, 1537–1544. doi:10.1097/00002030-200207260-00011.

Fitzmaurice, G. M., & Laird, N. M. (2000). Generalized linear mixture models for handling nonignorable dropouts in longitudinal studies. Biostatistics (Oxford, England), 1, 141–156. doi:10.1093/biostatistics/1.2.141.

Gray, R. H., Li, X., Wawer, M. J., Gange, S. J., Serwadda, D., Sewankambo, N. K., et al. (2003). Stochastic simulation of the impact of antiretroviral therapy and HIV vaccines on HIV transmission; Rakai, Uganda. AIDS (London, England), 17, 1941–1951. doi:10.1097/00002030-200309050-00013.

Huebner, D. M., Rebchook, G. M., & Kegeles, S. M. (2004). A longitudinal study of the association between treatment optimism and sexual risk behavior in young adult gay and bisexual men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 37, 1514–1519. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000127027.55052.22.

International Collaboration on HIV Optimism. (2003). HIV treatments optimism among gay men: an international perspective. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 32, 545–550. doi:10.1097/00126334-200304150-00013.

Kalichman, S. C., Nachimson, D., Cherry, C., & Williams, E. (1998). AIDS treatment advances and behavioral prevention setbacks: Preliminary assessment of reduced perceived threat of HIV-AIDS. Health Psychology, 17, 546–550. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.17.6.546.

Kelly, J. A., Otto-Salaj, L. L., Sikkema, K. J., Pinkerton, S. D., & Bloom, F. R. (1998). Implications of HIV treatment advances for behavioral research on AIDS: Protease inhibitors and new challenges in HIV secondary prevention. Health Psychology, 17, 310–319. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.17.4.310.

Kennedy, C., O’Reilly, K., Medley, A., & Sweat, M. (2007). The impact of HIV treatment on risk behaviour in developing countries: A systematic review. AIDS Care, 19, 707–720. doi:10.1080/09540120701203261.

Liden J., Low-Beer D., Archer J., Benn C., Schwartlander B., Rogerson A., and Schrade C. (2005). The Global Fund at three years. [Retrieved from: http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/files/about/replenishment/progress_report_en.pdf].

Lin, P., Simoni, J. M., & Zemon, V. (2005). The health belief model, sexual behaviors, and HIV risk among Taiwanese immigrants. AIDS Education and Prevention, 17, 469–483. doi:10.1521/aeap.2005.17.5.469.

Little, R. J. A. (1995). Modelling the drop-out mechanism in repeated measures studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 88, 125–134. doi:10.2307/2290705.

Mbulaiteye, S. M., Mahe, C., Whitworth, J. A. G., Nakiyingi, J. S., Ojwiya, A., & Kamali, A. (2002). Declining HIV-1 incidence and associated prevalence over 10-years period in a rural population in South-West Uganda: A cohort study. Lancet, 360, 41–46. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09331-5.

Moatti, J. P., Prudhomme, J., Traore, D. C., Juillet-Amari, A., Akribi, H. A., & Msellati, P. (2003). Access to antiretroviral treatment and sexual behaviours of HIV-infected patients aware of their serostatus in Cote d’Ivoire. AIDS (London, England), 17(Suppl. 3), S69–S77. doi:10.1097/00002030-200317003-00010.

Osmond, D. H., Pollack, L. M., Paul, J. P., & Catania, J. A. (2007). Changes in prevalence of HIV infection and sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men in San Francisco: 1997 2002. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1677–1683. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.062851.

Ostrow, D. E., Fox, K. J., Chmiel, J. S., Silvestre, A., Visscher, B. R., Vanable, P. A., et al. (2002). Attitudes towards highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with sexual risk taking among HIV-infected and uninfected homosexual men. AIDS (London, England), 16, 775–780. doi:10.1097/00002030-200203290-00013.

Schroder, K. E., Carey, M. P., & Vanable, P. A. (2003). Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: I. Item content, scaling, and data analytical options. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 76–103. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_02.

Smith, D. J. (2003). Imagining HIV/AIDS: morality and perceptions of personal risk in Nigeria. Medical Anthropology, 22, 343–372. doi:10.1080/714966301.

Stolte, I. G., Dukers, N. H., Geskus, R. B., Coutinho, R. A., & de Wit, J. B. (2004). Homosexual men change to risky sex when perceiving less threat of HIV/AIDS since availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy: A longitudinal study. AIDS (London, England), 18, 303–309. doi:10.1097/00002030-200401230-00021.

Stoneburner, R. L., & Low-Beer, D. (2004). Population-level HIV declines and behavioral risk avoidance in Uganda. Science, 304, 714–718. doi:10.1126/science.1093166.

UNAIDS and WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. (2005). Progress on global access to HIV antiretroviral therapy: An update on 3” by 5” (June).

Van de Ven, P., Kippax, S., Knox, S., Prestage, G., & Crawford, J. (1999). HIV treatments optimism and sexual behaviour among gay men in Sydney and Melbourne. AIDS, 13, 2289–2294.

Vanable, P. A., Ostrow, D. G., McKirnan, D. J., Taywaditep, K. J., & Hope, B. A. (2000). Impact of combination therapies on HIV risk perceptions and sexual risk among HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay and bisexual men. Health Psychology, 19, 134–145.

Weidle, P. J., Wamai, N., Solberg, P., Liechty, C., Sendagala, S., Were, W., et al. (2006). Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a home-based AIDS care programme in rural Uganda. Lancet, 368, 1587–1594.

Were, W. A., Mermin, J. H., Wamai, N., Awor, A. C., Bechange, S., Moss, S., et al. (2006). Undiagnosed HIV infection and couple HIV discordance among household members of HIV-infected people receiving antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 43, 1–5.

Zeger, S. L., Liang, K. Y., & Albert, P. S. (1988). Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics, 44, 1049–1060.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the counselors, field officers, clinical staff and the study participants for their time and commitment. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Ugandan Ministry of Health and The AIDS Support Organization. Furthermore, the authors thank Dr. George Rutherford for his comments on this manuscript and Theopista Wamala for her assistance with the references.

Sponsorship

The Home-Based AIDS Care (HBAC) project is funded by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bechange, S., Bunnell, R., Awor, A. et al. Two-Year Follow-Up of Sexual Behavior Among HIV-Uninfected Household Members of Adults Taking Antiretroviral Therapy in Uganda: No Evidence of Disinhibition. AIDS Behav 14, 816–823 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9481-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9481-2