Abstract

Homelessness and unstable housing have been associated with HIV risk behavior and poorer health among persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), yet prior research has not tested causal associations. This paper describes the challenges, methods, and baseline sample of the Housing and Health Study, a longitudinal, multi-site, randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of providing immediate rental housing assistance to PLWHA who were homeless or at severe risk of homelessness. Primary outcomes included HIV disease progression, medical care access and utilization, treatment adherence, mental and physical health, and risks of transmitting HIV. Across three study sites, 630 participants completed baseline sessions and were randomized to receive either immediate rental housing assistance (treatment group) or assistance finding housing according to local standard practice (comparison group). Baseline sessions included a questionnaire, a two-session HIV risk-reduction counseling intervention, and blood sample collection to measure CD4 counts and viral load levels. Three follow-up visits occurred at 6, 12, and 18 months after baseline. Participants were mostly male, Black, unmarried, low-income, and nearly half were between 40 and 49 years old. At 18 months, 84% of the baseline sample was retained. The retention rates demonstrate the feasibility of conducting scientifically rigorous housing research, and the baseline results provide important information regarding characteristics of this understudied population that can inform future HIV prevention and treatment efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV and homelessness are intimately connected, as the prevalence of HIV in homeless persons is three to nine times higher than those in stable housing (Allen et al., 1994; Culhane, Gollub, Kuhn, & Shpaner, 2001; Estebanez, Russell, Aguilar, Beland, & Zunzunegui, 2000; Fournier et al., 1996; Paris, East, & Toomey, 1996; Shlay et al., 1996; Torres, Mani, Altholtz, & Brickner, 1990; Zolopa, Hahn, Gorter, Miranda, & Wlodarczyk, 1994). Homeless persons are more likely to engage in behaviors that put themselves and others at risk for HIV infection including risky sexual behavior, injection drug use and needle sharing, and exchanging sex for money, drugs, or shelter (Allen et al., 1994; Burt, Aron, & Lee, 2001; Culhane et al., 2001; Fournier et al., 1996; O’Toole et al., 2004; Walters, 1999).

Preventing HIV transmission by persons diagnosed with HIV is a public health priority (Janssen et al., 2001). Individual and small group interventions to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors among persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) have been shown to be effective (Crepaz et al., 2006), but there is growing recognition of the importance of structural factors external to an individual that affect a person’s HIV transmission risk behaviors (Sumartojo, 2000). Effective public health interventions in the US include many structural interventions such as seat belt laws, taxation of tobacco products, water fluoridation, and lowering speed limits (Blankenship, Bray, & Merson, 2000). In HIV prevention, effective structural interventions include reducing perinatal HIV transmission by providing HIV medications to HIV-positive pregnant mothers (Mofenson, 2002), screening the blood supply for HIV (Dodd, 2004), requiring condom use by all patrons of sex establishments in Thailand, and increasing the availability of sterile injection equipment to injecting drug users (see Parker, Easton, & Klein, 2000 for discussion).

Housing is a structural intervention that has the potential to reduce HIV risk and improve health outcomes among homeless PLWHA (Sumartojo, 2000). One recent study reported reductions in rates of sex and drug risk behaviors among homeless or unstably housed HIV positive persons whose housing status improved compared to those whose housing did not change (Aidala, Cross, Stall, Harre, & Sumartojo, 2005). Other studies of PLWHA have shown that having housing was associated with better health as indicated by CD4 counts and viral load (Kidder, Wolitski, Campsmith, & Nakamura, in press; Knowlton et al., 2006). However, because these were observational studies, the causal relationship of housing and transmission risk could not be definitively determined.

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) are the primary scientific method used to establish causal relationships. However, conducting a RCT investigating the link between housing and health raises methodological, operational, and ethical challenges. Randomizing persons to a control condition in which they were required to remain homeless would be ethically untenable (Buchanan & Miller, 2006; Dail, 2001). In addition, implementing randomization has at times been resisted by service staff and/or community stakeholders (Mercier, Fournier, & Peladeau, 1992; Mowbray, Cohen, & Bybee, 1993; Toro, 2006).

There are also considerable challenges to the recruitment and retention of homeless persons with HIV/AIDS in a longitudinal study. Competing health concerns, distrust of government and institutions, and reluctance to provide identification and contact information are potential barriers to recruiting homeless PLWHA into research. Homeless persons or those at risk of becoming homeless are by definition a transient population, and persons living with HIV/AIDS may be particularly difficult to retain because of health problems. The result is that attrition in housing studies has often been high (Hwang, Tolomiczenko, Kouyoumdjian, & Garner, 2005). Even when attrition is relatively low, there is the possibility of selective attrition (i.e., those least successful in maintaining housing are less likely to be found for re-interview) (Camasso, 2003; Corsi, VanHunnik, Kwiatkowski, & Booth, 2006; Orwin, Scott, & Arieira, 2003; Schutt, Rosenheck, Penk, Drebing, & Seibyl, 2005; Toro, 2006; Wright, Allen, & Devine, 1995). Another issue is that providing housing is relatively costly. Thus it is important to show that the provision of housing not only achieves the desired outcomes, but also that it is a cost-effective strategy.

The current study built on previous research and attempted to anticipate and address the challenges in conducting this type of research. This study used a RCT to evaluate the effects of providing rental housing assistance to homeless PLWHA on physical health, access to medical care, treatment adherence, HIV risk behaviors, and mental health status. This paper describes the challenges, methods, and baseline sample of the Housing and Health Study, which is the only known housing-based HIV prevention intervention trial.

Methods

Study Goals

The primary goals of the Housing and Health Study were to examine the impact of providing rental housing assistance to PLWHA who were homeless or at severe risk of homelessness on (1) risk behaviors that might transmit HIV, (2) medical care access and utilization, (3) adherence to HIV medication therapies, and (4) mental and physical health. An additional goal was to examine the cost of housing as an HIV prevention intervention and assess whether the intervention was cost-effective relative to other HIV prevention and public health interventions.

Study Development

The Housing and Health Study was a collaboration between Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Office of HIV/AIDS Housing that administers the HOPWA (Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS) program. HUD was the lead agency on the housing portion of this project and provided expertise and funding for rental housing assistance. CDC was the lead agency on the research portion and provided expertise and funding for research activities. CDC also provided funding to enhance local service provider resources by supporting Housing Referral Specialists to assist with locating and securing housing. The project was guided throughout by an ethical commitment that no one’s opportunities for housing would be limited by the presence of the study in a community or by participating in the study (ethical issues are discussed in greater detail later in this paper). In order test all materials and procedures, a pilot study was conducted in Atlanta, GA, with 18 recently homeless persons living with HIV at a HOPWA funded housing agency.

The three study sites (Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Los Angeles, CA) were selected through a HOPWA Special Projects of National Significance grants competition. Applicants had to be currently receiving HOPWA funds and have an unmet housing need of at least 500 eligible persons. These HUD grantee agencies promoted the study in their community, recruited participants for the study, screened potential study participants for eligibility, and provided housing referral and support services to study participants. The grantees were essential partners in the research effort and were crucial to the success of the study. Periodic meetings and regular conference calls facilitated exchange of information and expertise across sites and helped cultivate local ‘ownership’ and enthusiasm for the project. The roles of grantee agency staff were distinct from those of study staff, as grantee agency staff did not participate directly in conducting the project research activities.

Each site had a Community Advisory Board (CAB) to provide input and feedback regarding study implementation, including recruitment practices, coordination of activities, and participant follow-up. Each CAB had broad representation including community-based organizations, city and county agencies, people who were homeless or formerly homeless, and people living with HIV/AIDS.

Prior to implementation, community meetings were held to publicize the study and to obtain public participation and stakeholder feedback. The goals and methods of the study (including the ‘lottery system’ for randomization) were explained and representatives of community agencies, advocates for the homeless, and people living with HIV had the opportunity to comment and provide feedback. We explained that this study did not deny housing to any participants. Participants in the comparison group were able to receive housing through all customary mechanisms that existed in the community. The housing resources brought into each community by the Housing and Health Study represented additional resources that would not otherwise have been available. Every assurance was made that no one’s opportunities for housing would be limited by their participation in this study or by the presence of this study in their community. All participants in both study groups received, at a minimum, standard housing services and an HIV transmission counseling intervention. Housing agency clients who did not participate in the study continued to be eligible for the same housing services that would have been available to them in the absence of the study. The response to the study in the communities was overwhelmingly positive, with questions typically focused on implementation issues such as how people would be recruited and retained.

The study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at CDC and the collaborating institutions conducting the research. The study also received approval of the questionnaire from the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB No. 0920-0628).

Study Design

The study was a longitudinal RCT with two groups and four assessment periods (baseline, 6, 12, 18 months). Data collection began in July 2004 and ended in January 2007. Each of the three study sites had a treatment and comparison group, with participants divided equally between the groups.

Treatment Group

Participants received HOPWA-funded rental housing assistance in conjunction with supportive services and case management. The rental housing assistance entitled recipients to long-term rental assistance for a housing unit of their choosing. The amount of housing assistance received by a study participant varied depending on the Fair Market Rent determined by HUD annually for each metropolitan area. The HOPWA program requires that each person receiving rental assistance pay 30% of his or her household’s monthly adjusted income. Study-funded Housing Referral Specialists assisted with finding housing and negotiating leases. Participants received referrals to other supportive services (e.g., health, mental health, drug and alcohol abuse treatment and counseling, nutritional services, home care) customarily provided by the local agencies.

Comparison Group

Participants received customary and usual services from the housing agencies and received referrals to case management. Participants met with the Housing Referral Specialists who provided assistance with obtaining temporary shelter and longer-term housing through existing resources and provided referrals for supportive services. Comparison group members were not required to remain in their current living situation in order to participate in this study and were not restricted in any way from accessing housing as it became available through other sources.

Recruitment and Screening

Using marketing initiatives and community outreach, HUD grantee agencies in the three cities advertised the study in their communities. Staff from community-based organizations were provided with information about the study and assisted in referring potential participants. Potential participants were invited to a central location or to call a toll-free number to obtain more information about the study. Those interested in the study were screened at a central location (typically the grantee agency) to determine housing eligibility and if determined eligible they were scheduled for an appointment at the study office, which was separate from the HUD grantee agency.

The screening and enrollment occurred in four cycles and took approximately 4 months to complete. People who came to the HUD grantee agency after the screening cycle was completed were advised of the dates for the next cycle. A multi-cycle enrollment scheme was chosen for the study to better accommodate the target population. Having only one enrollment period would have required some of the baseline session appointments to be scheduled three months from the enrollment date; such a delay would have created unnecessary attrition between enrollment and the baseline assessment. Instead, using multiple cycles, the period between enrollment and baseline assessment was no longer than 3 weeks.

A study office was established in each city, located in an area convenient and accessible to the target population. The office was designed to provide a friendly and welcoming place for study participants with convenient hours, snacks, and activities for children, as well as meeting requirements for privacy, medical specimen collection and storage, and electronic data transfer. Staff were sensitive to issues faced by HIV positive and homeless populations.

Eligibility

Participants were limited to HOPWA-eligible persons (HIV-seropositive, income less than 50% of the area median incomeFootnote 1) who were homeless or at severe risk of homelessness (defined below). HIV-seropositive status and income eligibility were confirmed through customary housing agency intake procedures. Participants were at least 18 years of age, able to provide informed consent, and able to complete study materials in English or Spanish (Chicago and Los Angeles only). Participants were not required to meet tests of sobriety or any type of treatment engagement as a condition of obtaining or maintaining housing.

Homeless

Persons who were sleeping in emergency shelters or other facilities for homeless persons, or places not meant for human habitation (e.g., cars, parks, sidewalks, abandoned buildings) were considered homeless. This also included persons who ordinarily lived in such places but were in a hospital or other institution on a short-term basis (30 consecutive days or less).

Severe Risk of Homelessness

Persons who were frequently relocated or who moved between temporary housing situations, so that housing was neither appropriate nor stable were considered to be at severe risk of homelessness.

Baseline Sessions

Baseline procedures included three separate sessions (see Fig. 1). During Visit 1 participants provided informed consent and were enrolled. Visit 2, approximately one week later, included a questionnaire, blood specimen collection for CD4 and viral load tests, and an HIV prevention intervention session. During Visit 3, approximately two weeks later, they received their blood test results, completed a second HIV prevention intervention session, and were randomized to treatment condition. Participants received $40 for the baseline sessions.

Visit 1: Enrollment

A staff person explained the study to potential participants, read the consent form aloud, and answered any questions. After obtaining informed consent, a brief set of contact information was collected.

Visit 2: Baseline Data Collection and First HIV Prevention Session

Baseline Questionnaire

A questionnaire with seven topic areas (see Table 1) was administered in individual sessions by a trained interviewer using a laptop computer. The questionnaire took approximately 90 minutes to complete. Data collection used both Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) and Audio Computer Assisted Self-Interviewing (ACASI) methods. In CAPI sections, the interviewer read aloud each item and entered the participant’s response into the computer. In ACASI sections, participants completed questions about sexual behavior, substance use, and traumatic events on the computer without the interviewer. The interviewer remained nearby to answer participant questions. A voice recording of each item and response options was heard through headphones and shown on the screen. ACASI provides a higher level of privacy to the participant, reduces concerns about confidentiality of responses to sensitive questions, and results in greater reporting of risk behaviors (Boekeloo, Schiavo, Rabin, Conlon, & Mundt, 1994; Kissinger et al., 1999; Kurth et al., 2004; Newman et al., 2002; Perlis, Des Jarlais, Friedman, Arasteh, & Turner, 2004; Riley et al., 2000).

Blood Specimen Collection and Testing

The project nurse or physician drew two blood specimens (total of 11 ml of whole blood). At the end of each day, the blood specimens were shipped to the CDC HIV Clinical Diagnostics Program laboratory to conduct HIV-1 viral load assay and CD4 lymphocyte subset assay (CD4/CD8 counts and percentages). The viral load test used was the Roche Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test, version 1.5, an in vitro nucleic acid test for the quantification of HIV-1 RNA in human plasma. The test is based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology and is sensitive enough to measure HIV-1 RNA over a range of 400 to 750,000 copies per ml.

Health First HIV Prevention Intervention: Session 1

An interventionist conducted the first of a two-session, client-centered HIV risk-reduction intervention, which was based on Project RESPECT, an effective intervention for STD clinic patients (Kamb et al., 1998). The intervention was adapted to address the needs of HIV-seropositive persons, including discussion of the risk of transmitting HIV to others and the risk to one’s own health of engaging in risky sex or injecting drugs. This first session took approximately 30 minutes and focused on HIV risk behaviors and developing a personalized risk-reduction plan.

Contact Information

Extensive contact information was collected to assist with contacting the participant (e.g., addresses, phone numbers, driver’s license number, places participant frequented, other people to contact such as friends or relatives).

Visit 3: Second HIV Prevention Session and Randomization

Provision of Lab Results

The project nurse or physician provided and explained the CD4 and viral load tests results in a private office, answered participant questions, and provided referrals for care.

Health First HIV Prevention Intervention: Session 2

The interventionist reviewed the effects of HIV on the immune system and the meaning of the test results. He or she discussed the participant’s access to care and the importance of adhering to HIV treatments. The risk reduction plan developed in the first session was reviewed and revised as necessary. This session took approximately 30–45 minutes.

Randomization

The interventionist explained the randomization process, ran the randomization program on the laptop, and informed the participant of his/her group assignment. The participant was immediately taken to an on-site Housing Referral Specialist who assisted the participant with either (a) activating the rental housing assistance and locating housing or (b) developing a plan for housing assistance (for those not receiving rental housing assistance). They also determined need for other supportive services and provided referrals.

Follow-up Sessions

Follow-up study sessions occurred 6, 12, and 18 months after the final baseline session. At each follow-up session, participants completed a shortened version of the baseline questionnaire (approximately 60 minutes) and provided another blood specimen. Participants were paid $55, $60, and $75 for the 6, 12, and 18 month follow-up sessions, respectively.

Participant Retention Strategies

To retain study participants following the baseline sessions, a multi-faceted tracing system was utilized that included field tracing staff, online databases, and specialized tracing searches. Field tracers were project staff (interviewers or interventionists) who were specifically trained and responsible for specific study participants. Attempts to locate each participant occurred three months after the baseline, 6, and 12 month sessions (i.e., halfway between each scheduled interview).

Tracing began with the most current location information available for participants and an individualized tracking plan was developed. Staff attempted to contact participants or his/her contacts (e.g., relative, case worker, friend) by phone, made personal visits to the locations where the study participant or his/her contacts might have been located, and followed whatever leads were available. There was also a toll free study ‘hotline’ that participants could call to provide information where they could be contacted and staff gave blank postage-paid ‘change of address’ postcards to participants. If these leads were exhausted, additional methods were used with some of the most effective including visiting known areas where homeless people gathered (e.g., soup kitchens, local shelters, outdoor areas), searching state prison inmate services and online jail/prison databases, and contacting case managers or other agency contacts. Another useful strategy was to send a letter to all addresses provided by the participant or other sources letting the participant know that the study was trying to reach them. Each attempt to contact participants was recorded, and the majority of the participants were able to be found with one or two contact attempts.

When a participant was contacted between follow-up periods they were given a ‘gift bag’ which included a note thanking them for their continued study participation, and items such as a weekly pill box, a plain knit cap, a food gift certificate, and/or a water bottle. Gift bags with similar contents were provided at all study sites during each of the three tracking contact periods. Several weeks before participants were eligible for their follow-up interview the contact process was repeated. The tracing staff person also then scheduled the follow-up session appointment.

All follow-up windows were calculated based from the date each participant completed his/her final baseline session. Thus, the ideal follow-up dates were 6, 12, and 18 months after the final baseline assessment session. The target time period for conducting follow-ups was up to 1 month before the follow-up date through 2 months after the follow-up date. These follow-up periods were fixed based on the date the participant completed the baseline assessment, regardless of when they completed a follow-up assessment. Nearly all participants were able to be interviewed during these time periods. However, there were a few participants who missed a follow-up session window (e.g., due to incarceration) but were able to be brought in to complete a session later. They were able to complete the follow-up session up to the point of the next follow-up period. However, there had to be at least 60 days between completing that session and the next session. If a participant missed a follow-up period they were still tracked and attempts were made to have them complete the subsequent follow-up session.

Data Analysis

For this paper baseline data were analyzed for all participants who completed a baseline questionnaire and a blood draw to examine the sociodemographic, housing status, and health status of study participants. This study was not designed to examine differences between sites in the intervention effects. However, we thought it important to describe the characteristics of the sample across sites to provide a better understanding of the participants in these geographically disparate areas. Thus, all variables were analyzed for site differences using Chi-square tests. All data analyses were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Cost Effectiveness Analysis

The cost effectiveness of the intervention was investigated by calculating the costs of delivering the intervention services and comparing this to the health benefits accrued. See Holtgrave et al. (this issue) for further information.

Results

Participants

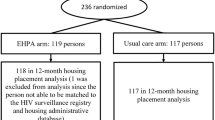

Baseline data collection was conducted from July 2004 through May 2005. Based on power calculations for rates of unprotected sex between treatment and comparison groups, we determined that 630 participants were needed to complete the randomization. A total of 665 participants completed Baseline Visit 1 and 653 (98%) returned for Visit 2 (Fig. 1). Following Visit 2, eight participants were deemed ineligible because they did not meet the definition of homelessness or severe risk of homelessness. In addition, one participant asked to be removed from the study and requested that his data be removed. Removing these nine participants resulted in 644 participants with baseline questionnaire data. Data from these participants are presented in this paper. Of these participants, 630 completed the third baseline visit (95% of Visit 1, 97% of Visit 2) and were randomized into the two study groups, with half (n = 315) in each group. Each of the three study sites had 105 participants in each of the two study groups.

Sociodemographics

The majority of study participants were male, although Baltimore had fewer males and Los Angeles had more (Table 2). Most were Black although there was a range with Baltimore having a higher percentage and Los Angeles lower percentage of Black participants. About half the participants were between 40 and 49 years old and most had a high school education or less, with a more highly educated sample in Los Angeles.

About half the participants reported they were heterosexual; another one-third identified as gay or lesbian (30% of males, 1% of females, 2% of transgenders). This differed by site, with more heterosexually-identified participants in Baltimore, followed by Chicago then Los Angeles, with the cities reversed for gay or lesbian participants. Most participants had never been married and few had children living with them, although Baltimore and Chicago had higher percentages for these variables than did Los Angeles. Eight participants completed the questionnaire in Spanish (six in Chicago, two in Los Angeles).

Most participants were not employed and the primary sources of income were public funding only (e.g., social security, TANF welfare payments, veteran’s benefits) or public sources in combination with private income (e.g., job, alimony, child support, gifts). There was greater unemployment in Los Angeles than Baltimore and Chicago. Household income was very low, with nearly all reporting less than $1,000 per month. Most respondents had been arrested and/or incarcerated in their lifetime. Incarceration rates differed significantly across sites, with Los Angeles participants reporting higher rates than Baltimore or Chicago.

There was variability in amount of time participants had been diagnosed with HIV, with 40% diagnosed for at least 10 years and nearly the same percentage reporting they had ever been diagnosed with AIDS. Los Angeles had a higher percentage of participants who had been diagnosed for more than 15 years and more who had been diagnosed with AIDS.

Participants were categorized based on lifetime history of behaviors that put them at greater risk for HIV infection including men who ever had sex with other men (MSM), ever engaged in injection drug use (IDU), ever had heterosexual sex, or other/not identified. Most were categorized as MSM or heterosexual, although there were also many IDUs. A larger percentage of participants in Los Angeles were MSM/IDU than the other two sites. There were also more MSM in Los Angeles than Chicago, with the fewest in Baltimore. However, Baltimore had a greater percentage of participants who were categorized as IDUs.

Health Status

Substantial numbers of participants had evidence of advanced HIV disease. Nearly a quarter had a CD4 count <200 per microliter (Table 2). The majority (68%) had a detectable HIV viral load (≥400 copies per milliliter), and 32% had a viral load of more than 55,000 copies per milliliter.

Housing Status

Information from the agencies conducting the HOPWA eligibility screening indicated that at the time of screening 53% of study participants met the study definition of homeless (50% in Baltimore, 46% in Chicago, and 62% in Los Angeles), and the remainder were at severe risk of homelessness.

In the questionnaire, participants were asked several questions about their living situations in the past 90 days. Items asked about (1) places they had spent at least one night in the past 90 days, (2) their current living situation (i.e., past 7 days), and (3) the place they had spent the most nights in the past 90 days (Table 2). For each question they were asked to select from a list of different living situations. Based on responses to these questions, respondents were categorized into one of three categories describing their recent housing status. Using these categories, 27% were recently homeless, 69% were unstably housed or at severe risk of homelessness, and 4% in their own place and facing severe risk of homelessness. The participants who reported being recently homeless had stayed in a shelter, public place, and/or on the street or outside. For those who had stayed in a shelter, the average was 37 days out of the last 90 days, in a public place was 33 days, and 28 days for those on the street or outside. Although persons were only eligible for the study if they were homeless or at severe risk of homelessness, a small number of participants reported being in their own place. The differences in housing status between screening and time of baseline questionnaire administration may be due to changes in housing status during that time period.

Participant Retention

For the 6-month follow-up, 91% (n = 576) of randomized participants completed the session, which decreased slightly to 87% (n = 550) at 12-months, and 85% (n = 533) for 18-month follow-up session (Fig. 1). A number of participants were not able to be interviewed at final follow-up primarily because of death (n = 32), incarceration (n = 26), or having moved to another area too far away to be interviewed (n = 8). Only 23 participants were not able to be located for final follow-up. Eight participants (1%) were deceased at 6 months and 19 (3%) at 12 months.

Seventy-nine percent of participants (n = 495) completed all four study sessions (baseline and three follow-up sessions), 11% completed three sessions, 6% completed two sessions, and 4% completed one session.

Discussion

Although evidence is accumulating that housing is associated with reduced HIV risk behaviors and positive health outcomes, previous research has not definitively determined that housing was responsible for the outcomes. This multi-site, longitudinal RCT is the first effort to rigorously evaluate housing as a structural HIV prevention intervention for homeless or unstably housed PLWHA. The results presented in this paper demonstrate the feasibility of conducting this type of research with a vulnerable, transient, and cautious population.

The research questions examined in the Housing and Health Study and the nature of the population present challenges to conducting methodologically rigorous research. The retention results show that it is possible to maintain high levels of engagement over time among a very transient population. Early in the study we developed an infrastructure and procedures to engage participants in the study and build rapport with them in order to maximize the ability to track participants, with the goal of maintaining high retention rates across follow-up periods. These efforts were successful, with over 84% of participants retained at 18-months. Although there was some differential attrition across groups, the difference was only 5% at final assessment. Future analyses will compare baseline characteristics of persons lost to follow-up with those who were retained to inform future longitudinal studies with this population and to identify participant characteristics associated with attrition that might confound the planned outcome analyses.

In addition to the longitudinal results that are anticipated from this study, the baseline data provide important information about this understudied population. The sociodemographic profile of participants in this study was similar in some ways to prior descriptions of homeless populations (e.g., largely male, single, disproportionately Black) (Burt et al. 2001; US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2000) and reflects the general characteristics of the HIV epidemic in the US (e.g., disproportionately Black) (CDC, 2005). There were some differences between sites, which reflect differences in the nature of the HIV epidemic in these areas and highlights the potential need to tailor housing, care, and prevention services to the characteristics of homeless PLWHA in different areas of the country. There may also be differences in risk and health behaviors (e.g., HIV risk, medical care use) depending on locale and the services available to PLWHA. This underscores the importance of gathering local data to assess the needs of PLWHA in specific communities.

The data also showed considerable need for medical care and treatment, as about half the participants had CD4 levels indicating a need for antiretroviral treatment. A quarter of participants had very high HIV viral load levels, indicating that they are at substantial risk for HIV disease progression and HIV transmission if they have unprotected sex. There also were high levels of involvement with the criminal justice system and lifetime incarceration. This suggests the need for interventions, such as Comprehensive Risk Counseling and Services (CRCS) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006), that address multiple issues affecting the health and well-being of homeless and unstably housed PLWHA. The results also suggest the potential utility of HIV prevention within the criminal justice system, such as conducting HIV prevention interventions during incarceration and transition planning prior to release to ensure access to medical care and housing for HIV-seropositive inmates.

Throughout the study development process, great attention was paid to ethical concerns associated with designing an intervention to study the association between housing and health. Because people living with HIV who are homeless or at severe risk of losing housing are a highly vulnerable population, we took care to ensure that participants’ rights and privacy concerns were addressed throughout the study. Described below are some of these issues and how they were addressed.

One potential ethical issue was the possibility of concerns about providing a blood specimen for testing. In part this was addressed by explaining the importance of the blood tests as a primary outcome that would allow the study to examine the effects of housing using biological markers of disease progression. In addition, the issue was raised with providers who serve this population, as well as participants in the pilot study (described previously). None of these groups were concerned about participants having to provide the blood specimens. All the materials describing the study explained that the blood draw would be a part of the procedures, and this was also explicitly described in the consent form. To our knowledge there were no concerns about the blood draw raised by any participants in the study. In fact, many participants perceived receiving the blood test results and an explanation of the results provided by a trained medical provider as a benefit of participating in the study.

It was important to the researchers that participants in the comparison group were provided benefits beyond housing rental assistance. Comparison group participants received additional resources as a result of this study, including Health First HIV prevention counseling and clinical tests to monitor HIV viral load and immune system status. In addition, immediately after randomization, the comparison group participants met with a study-funded housing referral specialist to discuss housing options and to receive personal attention to their specific needs. Based on this discussion, they received referrals for temporary shelter, housing assistance, and other social services that were tailored to their needs. Because care was taken to ensure that participants in the comparison group also received benefits for participating, there was some risk that the study’s ability to detect differences between the groups may have been reduced. However, ethical considerations were always paramount in the design of the study and it was considered more important to provide these benefits to all participants and risk masking some of the outcomes.

An important issue in the design and implementation of the study was that participants in the comparison group not be denied housing from other sources as a requirement of being in the study. Thus, the study was an evaluation of faster access to rental housing assistance compared with customary access to housing in the participating communities. This allowed for the likelihood that some proportion of the comparison group participants would receive housing during the course of the study. It was also likely that there would be crossover in the other direction, with participants in the treatment group losing their housing for various reasons (e.g., incarceration, lease violations). Although allowing crossover potentially affects the study results, it was ethically important to the researchers and participating communities that comparison group participants be afforded every opportunity to receive housing through other mechanisms available in the community.

Although this study has a number of methodological strengths, it also has some limitations. The questionnaire data were all self-report, which is potentially subject to socially desirable responding. We attempted to minimize this by using ACASI for more sensitive questions, as previously discussed. In addition, self-report data could be subject to recall biases or forgetting, although we tried to reduce this likelihood by having the recall period primarily be the past 90 days rather than a longer recall period and by including objective measures of health status (CD4 and viral load). This study was conducted in several sites across the US, but participants may not be representative of homeless PLWHA across the country. Attempts were made to increase the representativeness of the sample in each city by advertising the study widely prior to screening and by having multiple waves of enrollment to provide multiple opportunities for participating in the study.

Despite challenges presented by conducting this type of study, research of this kind is important. Addressing the housing needs of homeless PLWHA will not only provide a basic necessity to members of this vulnerable group, but it is hypothesized that having stable housing will result in positive mental and physical health outcomes and will decrease HIV transmission risk behaviors. The results of the Housing and Health Study will provide important information on the effectiveness of housing as a structural intervention for homeless PLWHA. If the results of this study provide evidence that housing is an effective structural intervention and that it is cost effective, it could have a public health impact by not only adding an effective intervention to the HIV prevention cache, but also by providing policy makers with evidence that the provision of affordable housing assistance to PLWHA is cost effective and beneficial to the communities in which this special needs population reside.

Notes

Income for HOPWA eligibility is 80% of the area median income, but was lower for the purposes of this study.

References

Aidala, A., Cross, J. E., Stall, R., Harre, D., & Sumartojo, E. (2005). Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: Implications for prevention and policy. AIDS and Behavior, 9, 251–265.

Allen, D. M., Lehman, S., Green, T. A., Lindegren, M. L., Onorato, I. M., Forrester, W., et al. (1994). HIV infection among homeless adults and runaway youth, United States, 1989–1992. AIDS, 8, 1593–1598.

Blankenship, K. M., Bray, S. J., & Merson, M. H. (2000). Structural interventions in public health. AIDS, 14, S11–S21.

Boekeloo, B. O., Schiavo, L., Rabin, D., Conlon, R. T., Jordan, C. S., & Mundt, D. J. (1994). Self-reports of HIV risk factors by patients at a sexually transmitted disease clinic: Audio vs. written questionnaires. American Journal of Public Health, 84, 754–760.

Buchanan, D. R., & Miller, F. G. (2006). A public health perspective on research ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics, 32, 729–733.

Burt, M., Aron, L. Y., & Lee, E. (2001). Helping America’s homeless: Emergency shelter or affordable housing? Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Camasso, M. J. (2003). Quality of life perception in transitional housing demonstration projects: An examination of psychosocial impact. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 3, 99–118.

Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. (2005). HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2004 (Vol. 16). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2006). Comprehensive risk counseling and services (CRCS) implementation manual. Retrieved January 22, 2007 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/prev_prog/CRCS/resources/CRCS_Manual/index.htm.

Corsi, K. F., VanHunnik, B., Kwiatkowski, C. F., & Booth, R. E. (2006). Computerized tracking and follow-up techniques in longitudinal research with drug users. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology, 6, 101–110.

Crepaz, N., Lyles, C., Wolitski, R., Passin, W., Rama, S., Herbst, J., et al. (2006). Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS, 20, 143–157.

Culhane, D. P., Gollub, E., Kuhn, R., & Shpaner, M. (2001). The co-occurrence of AIDS and homelessness: Results from the integration of administrative databases for AIDS surveillance and public shelter utilisation in Philadelphia. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55, 515–520.

Dail, P. W. (2001). Introduction and concluding observations: Special Issue on Homelessness. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(6), 6–13.

Dodd, R. Y. (2004). Current safety of the blood supply in the United States. International Journal of Hematology, 80, 301–305.

Estebanez, P. E., Russell, N. K., Aguilar, M. D., Beland, F., & Zunzunegui, M. V. (2000). Women, drugs and HIV/AIDS: Results of a multicentre European study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29, 734–743.

Fournier, A. M., Tyler, R., Iwasko, N., LaLota, M., Shultz, J., & Greer, P. J. (1996). Human immunodeficiency virus among the homeless in Miami: A new direction for the HIV epidemic. American Journal of Medicine, 100, 582–584.

Holtgrave, D. R., Briddell, K., Little, E., Bendixen, A. V., Hooper, M., Kidder, D. P., Wolitski, R. J., Harre, D., Royal, S., Aidala, A., for the Housing and Health Study Team (this issue). Cost and threshold analysis of housing as an HIV prevention intervention. AIDS and Behavior (this issue).

Hwang, S. W., Tolomiczenko, G., Kouyoumdjian, F. G., & Garner, R. E. (2005). Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 29(4), 311–319.

Janssen, R. S., Holtgrave, D. R., Valdiserri, R. O., Shepherd, M., Gayle, H. D., & De Cock, K. M. (2001). The Serostatus approach to fighting the HIV epidemic: Prevention strategies for infected individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 91(7), 1019–1024.

Kamb, M. L., Fishbein, M., Douglas, J. M., Rhodes, F., Rogers, J., Bolan, G., et al. (1998). Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 1161–1167.

Kidder, D. P., Wolitski, R. J., Campsmith, M. L., & Nakamura, G. V. (in press). Health status, health care use, medication use, and medication adherence in homeless people living with HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health.

Kissinger, P., Rice, J., Farley, T., Trim, S., Jewitt, K., Margavio, V., et al. (1999). Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behavior research. American Journal of Epidemiology, 149, 950–954.

Knowlton, A., Arnsten, J., Eldred, L., Wilkinson, J., Gourevitch, M., Shade, S., et al. (2006). Individual, interpersonal, and structural correlates of effective HAART use among urban active injection drug users. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 41(4), 486–492.

Kurth, A. E., Martin, D. P., Golden, M. R., Weiss, N. S., Heagerty, P. J., Spielberg, F., et al. (2004). A comparison between audio computer-assisted self-interviews and clinician interviews for obtaining the self history. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 31, 719–726.

Mercier, C., Fournier, L., & Peladeau, N. (1992). Program evaluation of services for the homeless: Challenges and strategies. Evaluation and Program Planning, 15, 417–426.

Mofenson, L. M. (2002). U.S. Public Health Service Task Force recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-1 infected women for maternal health and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV-1 transmission in the United States. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 51, 1–38.

Mowbray, C. T., Cohen, E., & Bybee, D. (1993). The challenge of outcome evaluation in homeless services: Engagement as an intermediate outcome measure. Evaluation and Program Planning, 16, 337–346.

Newman, J. C., Des Jarlais, D. C., Turner, C. F., Gribble, J., Cooley, P., & Paone, D. (2002). The differential effects of face-to-face and computer interview modes. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 294–297.

Orwin, R. G., Scott, C. K., & Arieira, C. R. (2003). Transitions through homelessness and factors that predict them: Residential outcomes in the Chicago Target Cities treatment sample. Evaluation and Program Planning, 26, 379–392.

O’Toole, T. P., Gibbon, J. L., Hanusa, B. H., Freyder, P. J., Conde, A. M., & Fine, M. J. (2004). Self-reported changes in drug and alcohol use after becoming homeless. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 830–835.

Paris, N. M., East, R. T., & Toomey, K. E. (1996). HIV seroprevalence among Atlanta’s homeless. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 7, 83–93.

Parker, R. G., Easton, D., & Klein, C. H. (2000). Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: A review of international research. AIDS, 14, S22–S32.

Perlis, T. E., Des Jarlais, D. C., Friedman, S. R., Arasteh, K., & Turner, C. F. (2004). Audio-computerized self-interviewing versus face-to-face interviewing for research data collection at drug abuse treatment programs. Addiction, 99, 885–896.

Riley, E. D., Robnett, T. J., Vlahov, D., Vertefeuille, J., Strathdee, S. A., & Chaisson, R. E. (2000). Computer-assisted self-interviewing for HIV and tuberculosis risk factors among injection drug users participating in a needle exchange program. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151, S55.

Schutt, R. K., Rosenheck, R. E., Penk, W. E., Drebing, C. E., & Seibyl, C. L. (2005). The social environment of transitional work and residence programs: Influences on health and functioning. Evaluation and Program Planning, 28, 291–300.

Shlay, J. C., Blackburn, D., O’Keefe, K., Raevsky, C., Evans, M., & Cohn, D. L. (1996). Human immunodeficiency virus seroprevalence and risk assessment of a homeless population in Denver. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 23, 304–311.

Sumartojo, E. (2000). Structural factors in HIV prevention: Concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS, 14, S3–S10.

Toro, P. A. (2006). Trials, tribulations, and occasional jubilations while conducting research with homeless children, youth, and families. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52(2), 343–364.

Torres, R. A., Mani, S., Altholtz, J., & Brickner, P. W. (1990). Human immunodeficiency virus infection among homeless men in a New York City shelter: Association with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Archives of Internal Medicine, 150, 2030–2036.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (2000). National evaluation of the housing opportunities for persons with AIDS program (HOPWA). Washington, DC: HUD Office of Policy Development and Research.

Walters, A. S. (1999). HIV prevention in street youth. Journal of Adolescent Medicine, 25, 187–198.

Wright, J. D., Allen, T. L., & Devine, J. A. (1995). Tacking non-traditional populations in longitudinal studies. Evaluation and Program Planning, 18, 267–277.

Zolopa, A. R., Hahn, J. A., Gorter, R., Miranda, J., & Wlodarczyk, D. (1994). HIV and tuberculosis infection in San Francisco’s homeless adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 455–461.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many people who made this study a success. In addition to the authors of this paper, the Housing and Health Study members (in alphabetical order) include Arturo Bendixen (AIDS Foundation of Chicago), Kate Briddell (City of Baltimore, Department of Housing and Community Development), Shahry Deyhimy (City of Los Angeles Housing Department), Paul Dornan (HUD), Myrna Hooper (Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles), Jennafer Kwait (RTI), Fred Licari (RTI), Shirley Nash (City of Chicago Department of Public Health), Sherri L. Pals (CDC), William Rudy (HUD), and David Vos (HUD). We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Rusty Bennett, Maria Caban, Sylvia Cohn, Lynne Cooper, Jay Cross, Maria DiGregorio, Clyde Hart, Kirk Henny, Kelly Kent, Lee Lam, Eugene Little, Ellen McCarty and Jerusalem House, Joyce Moon Howard, Noelle Richa, Danny Ringer, Randy Russell, Ruth Schwartz, and Tom Spira. We would like to thank the collaborating HUD grantee agencies in each city as follows: City of Baltimore Department of Housing and Community Development, City of Chicago Department of Public Health, AIDS Foundation of Chicago, City of Los Angeles Housing Department, Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, Shelter Partnership, Housing Authority of the County of Los Angeles, County of Los Angeles Office of AIDS Programs and Policies, Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Funding for the research study was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to RTI under contract 200-2001-0123, Task 9 and funding for tenant-based rental housing assistance was provided by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kidder, D.P., Wolitski, R.J., Royal, S. et al. Access to Housing as a Structural Intervention for Homeless and Unstably Housed People Living with HIV: Rationale, Methods, and Implementation of the Housing and Health Study. AIDS Behav 11 (Suppl 2), 149–161 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9249-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9249-0