Abstract

Local sustainable food systems have captured the popular imagination as a progressive, if not radical, pillar of a sustainable food future. Yet these grassroots innovations are embedded in a dominant food regime that reflects productivist, industrial, and neoliberal policies and institutions. Understanding the relationship between these emerging grassroots efforts and the dominant food regime is of central importance in any transition to a more sustainable food system. In this study, we examine the encounters of direct farm marketers with food safety regulations and other government policies and the role of this interface in shaping the potential of local food in a wider transition to sustainable agri-food systems. This mixed methods research involved interview and survey data with farmers and ranchers in both the USA and Canada and an in-depth case study in the province of Manitoba. We identified four distinct types of interactions between government and farmers: containing, coopting, contesting, and collaborating. The inconsistent enforcement of food safety regulations is found to contain progressive efforts to change food systems. While government support programs for local food were helpful in some regards, they were often considered to be inadequate or inappropriate and thus served to coopt discourse and practice by primarily supporting initiatives that conform to more mainstream approaches. Farmers and other grassroots actors contested these food safety regulations and inadequate government support programs through both individual and collective action. Finally, farmers found ways to collaborate with governments to work towards mutually defined solutions. While containing and coopting reflect technologies of governmentality that reinforce the status quo, both collaborating and contesting reflect opportunities to affect or even transform the dominant regime by engaging in alternative economic activities as part of the ‘politics of possibility’. Developing a better understanding of the nature of these interactions will help grassroots movements to create effective strategies for achieving more sustainable and just food systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

We’ve been on this organic journey for 20 years now and we just dropped our organic certification…David Neufeld who has an organic greenhouse in Boissevain, he’s done the same thing… I think local is the new thing, I mean organic has been corporatized now to the point where there are Walmarts and everyone else into it. You’ve got to do something to stay one step ahead of them. I think local is one thing that they can’t steal from you (Robert Guilford, Manitoba, 2006).

When we interviewed the post-organic farmer Robert Guilford in 2006, there was already a palpable buzz across North America about the prospects of a local food revolution. Livestock farmers who were still reeling from the BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy or Mad Cow Disease) crisis, declining farm incomes, and uncertainty around declining rural populations and infrastructure were beginning to question their extreme dependence on export markets and the concentration of power in multinational corporations (Anderson and McLachlan 2012). At the same time, urban consumer interest in local food was growing, fueled by popular books (e.g. The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan) and documentary films (e.g. Food, Inc.) celebrating the virtues of these alternatives (Allen 2008). Farmers and ranchers were also interested in alternatives but were disenchanted with the conventionalization of organic agriculture (Guthman 2004). Many saw local food as impervious to cooptation by the dominant agri-food system. They hoped that direct marketing would help them to build stronger connections with urban customers and would lead to a new food culture based on interest in healthy and sustainably produced food. A decade later, local food has become a mainstream discourse in food politics and there are many indications that its role in the food system is growing. Its potential for influencing meaningful change and its role as a farm livelihood strategy, however, are hotly contested (see Hinrichs 2003; Alkon 2013; Busa and Garder 2014). Can local food be developed and expanded in ways to foster a more sustainable and just food future? Or is it being coopted like its organic precursor? How do relationships among grassroots initiatives, governments, corporations, and institutions play in creating this food future? These are some of the timely questions this article will seek to address.

Many advocates of local food are hopeful about the place of local food in a transition towards a sustainable food system (e.g. Lutz and Schachinger 2013). Using Gibson-Graham’s (2006) ‘politics of possibility’, many have claimed that local food and community economies of food are contributing to substantial and potentially transformative change (Blay-Palmer et al. 2015; Ballamingie and Walker 2013). From this perspective, researchers are examining how new social, cultural and environmental relations in local food economies are fostering democratic social relations, agroecological practices, and new political perspectives which are a part of a transition to a more sustainable and just food system (see Friedland 2010; Clancy and Ruhf 2010; Levkoe 2014; Blay-Palmer et al. 2015). Yet others argue that the local food ‘movement’ inevitably reflects the tenets of the neoliberal food system and are at best only a marginal component of a dominant system based on capitalist, industrial, and productivist agriculture and food policies and practices (see Guthman 2008a; Johnston et al. 2009; Adams and Shriver 2010; Allen 2010; Busa and Garder 2014). Despite these binary perspectives, it is increasingly clear that local food politics and practices are heterogeneous (Holloway et al. 2007; Ilbery and Maye 2005; Watts et al. 2005). These spaces of local food can be both sites of possibility and of domination and there is a need to better understand these dynamics and why they change over time.

At this juncture in the politics and practice of local food systems, it is more important than ever to understand how power relationships between grassroots organization and government and corporations unfold. The goal of this article is to better understand the processes and possibilities for change in the food system and to develop conceptual tools to articulate the relationship between grassroots and government in community food systems. Our empirical data where we examine local food systems from the perspective of North American farmers and ranchers, their efforts to develop local food economies and their experiences in navigating their relationships with the wider food system as mediated by government policy and regulation. From our analysis of cross-regional survey and interview data and an in-depth case study in the Canadian province of Manitoba, we introduce a novel and dynamic typology of the interactions between grassroots and government providing a relational analysis of how a governmentality–politics of possibility frameworks plays out in local food systems. This grounded theory is interpreted using two theoretical bodies of literature—Foucault’s governmentality and Gibson-Graham’s ‘politics of possibility.’ Before turning to our empirical analysis, we review these literatures in the context of food and agriculture governance in the following section. Ultimately, our goal is to support the development of autonomous, sustainable and just food systems by providing a critical framework to understand how autonomy is often undermined by government, but as importantly, how grassroots actors and networks can gain more agency and collective control of food systems.

Making subjects in the food system: governmentality and the ‘politics of possibility’

The dominant food system in the Global North reflects the wider political economic context of neoliberal capitalism where industrial production methods, free-market trade, and export-oriented agriculture are supported and promoted by multi-national corporations and government policy (Friedmann 1993; Akram-Lodhi 2013; Blay-Palmer et al. 2015). These neoliberal ideologies become embedded in society through modes of governmentality, which exert power by shaping subjectivities, or the ways that individuals understand themselves, their agency, and how they relate to the rest of society, by shifting what is considered to be ‘common sense’ (Allen 2008; Dowling 2010; Kurtz et al. 2013; Busa and Garder 2014). The political and social construction of governable subjects has been central to the neoliberal project and is an important and pervasive mode of power and control in food systems (Guthman 2008a, b; Harris 2009).

Governmentality was first developed by Michel Foucault (1991, 1994) to examine the historical transition from sovereign states ruled by monarchs to democracies wherein governments needed to convince citizens that government and other public institutions were necessary to keep social order. Processes of creating new subjects through governmentality involve re-shaping social norms, discourses, and subjectivities over time in ways that legitimize the role of the nation-state and the free market as the dominant domains of social organization and which served to marginalize family, community and civil society as sites of agency (Foucault 1991). This process involves a shift from direct government of individuals to the ‘conduct of conduct’ where processes of self-regulation and subjectification came to be the primary mode of controlling the citizenry (Foucault 1991). Additionally, Foucault argued that governments use technologies such as the tracking of populations through censuses, regulation and the management of public health, in order to legitimize their management of the economy and the state (Foucault 1990). Today, powerful actors including government and corporations reproduce neoliberal subjectivities through processes of governmentality, which simultaneously limit alternative practices and subjectivities and create a common-sense capitalist hegemony (Gibson-Graham 2006).

In North America, corporations and governments shape food systems through regulatory, policy, and market mechanisms (Denny et al. 2016), but also through the subtler power that comes from manipulating attitudes and social norms through technologies of governmentality (Foucault 1991; Guthman 2008a, b). As a result, these mainstream institutions have marginalized practices, technologies, and farming systems that challenge the importance of increasing yield or the ideologies of neoliberalism (Clark et al. 2010; Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011; Stuart and Worosz 2011; Hatt and Hatt 2011; Denny et al. 2016). In many ways, neoliberalism is an extension of existing capitalist values, but with a further emphasis on individualism, devolution of government power, erosion of the welfare state and reorganization of society based on market relations (Dowling 2010; Eaton 2013).

In this context, mainstream agriculture policy and discourse have increasingly inculcated market-oriented agricultural subjectivities that fit into the neoliberal and productivist agricultural development model while devaluing alternative practices and subjectivities (Anderson and McLachlan 2012; McMahon 2013; Denny et al. 2016). Smaller scale farmers and community food systems that often have multifunctional benefits to society have, in turn, been marginalized to the detriment of the environment and food culture to the degree that rural communities and family farmers now face ongoing crisis and continuous decline (Cushon 2003; McMahon 2009; Anderson and McLachlan 2012). Similarly, governments act to invisibilize or ignore emerging alternative food initiatives while characterizing them as ‘niches’ that should be incorporated into the dominant system (Andrée et al. 2010; Ilbery et al. 2010), as doomed to failure (Harris 2009), or even as dangerous or unsafe (Kurtz et al. 2013). Productivist policies, which emphasize ever-increasing yields, patented technologies and the reduction of labor input to maximize profit, are enforced through market deregulation and privatization. The shift towards neoliberal, productivist policies are notable with respect to seed laws, supply managed markets, and agricultural subsidies and create path dependencies on farms by enabling some production and marketing options while disabling others (Guthman 2004; Desmarais and Wittman 2014). Finally, the neoliberal and productivist paradigm is further entrenched through the ‘art’ of governmentality that encourages individuals to regulate their own behavior to conform to the social norms that have been created by the dominant discourses of government and other powerful actors in the food system (Foucault 1991; Dressler 2014). Many producers in North America have internalized this productivist paradigm so that being a “good farmer” is increasingly understood as excelling at high input, high output production systems to maximize production (McGuire et al. 2013).

Using the example of food safety policies, neoliberal economic rationalities continue to trump other considerations, such as health, environment, and community, and where the responsibility for managing risk is shifted to corporations rather than third-parties such as government inspectors (Dunn 2003; Stuart and Worosz 2011; Hatt and Hatt 2011; Thompson and Lockie 2013; Denny et al. 2016). As part of the process of trade liberalization and de-regulation both corporate and bureaucratic actors are promoting a technology intensive science-based risk management approach to food safety (Miewald et al. 2013b; Busa and Garder 2014). When food safety crises occur, companies and public officials have effectively neutralized public concerns over the systemic causes of mass outbreaks of food-borne illness which include the increasing concentration of processing facilities, poor working conditions, and inadequate inspection regimes (McMahon 2013). Powerful corporate and government actors manage these crises by engaging in what Stuart and Worosz (2011) refer to as ‘anti-reflexive’ practices to justify ignoring calls for wider system change. During food safety crisis, corporations and public relations experts have manipulated the debate to avoid blame, by shifting it to other sources of contamination, blaming victims for poor food handling, and appealing to ideals of profitability and technology, all of which act to deter more radical changes to the food system (Stuart and Worosz 2011). Thompson and Lockie (2013) have explicitly labeled these types of actions in food safety regulation as ‘technologies of governmentality’ and have explored power of private food standards to change on-farm practices and how farmers have contested this process.

Public fears over food safety have thus been channeled by public health professionals and governments to implement strict phytosanitary procedures by appealing to consumer trust in the neoliberal logics of technology, science, and entrepreneurship, regardless of whether or not these procedures actually result in safer food (Gouveia and Juska 2002; DeLind and Howard 2008; McMahon 2009; Stuart and Worosz 2011; Miewald et al. 2013b). Consequently, despite the growing interest in developing local food systems, the regulatory context has undermined the trust that direct marketers rely upon through the construction of farmer and consumer subjectivities that are deeply committed to centralized and individualistic modes of managing risk (Dubuisson-Quellier and Lamine 2008). The resulting subjectivities undermine the potential for communities to support ecological and sustainable production practices and food systems and alternate pathways of rural economic development (McMahon 2009; Miewald et al. 2013b; da Cruz and Menasche 2014). As a result, the neoliberalization of food safety policies has been shown to contribute to the loss of small-scale processing facilities, the centralization of food processing, the consolidation of corporate power, and increased food insecurity in rural and northern communities across North America (Stuart 2008; GRAIN 2011; Hassanein 2011; Miewald et al. 2013a, b).

However, rather than simply complying with this uneven power dynamic, individuals and groups located in grassroots civil society continually cultivate alternative practices and subjectivities based on values and approaches that reflect priorities negotiated in alternative food economies (Marsden and Franklin 2013; Ballamingie and Walker 2013; Levkoe and Wakefield 2013; Blay-Palmer et al. 2015). Local food systems can thus reflect what Gibson-Graham call a ‘politics of possibility’ where these diverse community-based economic initiatives create new possibilities for decentralized alternatives to the dominant food system (Gibson-Graham 1996, 2006). In opposition to the dominating narrative of a neoliberal food subject, many alternative food systems challenge the ways that individuals define ‘common sense’ understandings of good, safe food and thus create new possibilities for change while cultivating their own agency (Gibson-Graham 2006). Although powerful processes of neoliberal governmentality have created consenting and self-governing subjects, it is equally true that these subjectivities are not fixed. Gibson-Graham (2006) point out that there are always various power relations, and various subject positions and thus the subjugation that results from governmentality is regularly resisted, adapted, and subverted, even though this may be difficult to observe through the hegemonic lens of neoliberal capitalism. Citizens drive this change through a range of political and practical acts in the construction of alternative economies and social systems which foster new subjectivities and challenge the government control of social norms and discourse (see Escobar 2001; Hinrichs 2003; Harris 2009; Allen 2010; Dowling 2010; Blay-Palmer et al. 2015). Equally important is that collective action by grassroots communities can cultivate critical awareness and new understandings of individuals themselves through a process of re-subjectification that build on the resistance to neoliberal governmentality (Gibson-Graham 2006, 2008).

The concepts of ‘politics of possibility’ and ‘community economies’ have been used effectively to explore how alternative food systems are working to create sites that are “resocialised, repoliticised, place-based […] in which an interdependent commerce is understood as ethical praxis” (Ballamingie and Walker 2013, pp. 530–531). Similarly, Blay-Palmer et al. (2015) argue that exploring food systems is an important way to understand wider system change because “food offers one way forward as communities re-invent the economic and political terms on more sustainable grounds” (p. 15). Local food initiatives become testing grounds for alternative economic systems and social relations because they emphasize collective processes that are highly adaptable and able to address related technical, social, economic and political problems as they arise (Allen 2010; Ballamingie and Walker 2013; Wilson 2013). As these community food initiatives coalesce and transform local relationships and politics, they are also becoming further entangled into wider and more diverse movements for social transformation (Escobar 2001; Hassanein 2003). Parallel conflicts over subjectivities and narratives are also playing out in the global struggle for defining ‘agroecology’ where farmers are resisting its cooptation by corporations and governments (Anderson et al. 2015). Community food initiatives, including more radical variants grounded in food sovereignty, food democracy, and food justice, arguably represent components of a new social movement opposed to the global agri-food system (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011).

Although both governmentality and the politics of possibility have each been used to examine local and alternative food systems in the literature (see Harris 2009; Thompson and Lockie 2013; Ballamingie and Walker 2013; Dressler 2014; Blay-Palmer et al. 2015), their combined influence has been underdeveloped thus far as they relate to their impact on food systems and farmers themselves. Thus, our grounded theory provides insight into the intersection between governmentality and the politics of possibility in the everyday lives of farmers by examining farmer’s encounters and responses to government policy and regulation. In the next section, we describe the methodology used in our cross-regional study. We then present our analysis of participants’ experiences with government support programs for direct marketing and food safety regulations. From these data, we develop a four-part typology of containing, coopting, contesting, and collaborating that we explore in detail using an illustrative case study based in the Canadian Province of Manitoba. This novel typology provides a nuanced framework to understand the dynamic interplay between the implicit and overt control of practices and subjectivities by government and the countervailing modes by which actors assert their own interests, autonomy, and agency.

Mixed methods and grounded theory approach

Our data collection focused on the experiences of farmers who direct market their products in a capitalist, industrial food system in different regions of North America. As a result, this allowed us to understand the creation of farmer subjectivities as influenced by governments and corporations and their own efforts to engage in alternative economic activities. Our mixed methods approach (Creswell and Plano Clark 2007) combined Likert-scaled and open-ended survey questions, individual interviews, and case study methods in order to analyze across a wide diversity of ecological and geographical contexts and experiences. We created a master list of 227 farms by conducting a systematic Internet search using national, provincial/state and regional databases that list farmers and ranchers who direct market meat in three western Canadian provinces (Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia) and three western American States (Oregon, North Dakota and South Dakota). Between September 2009 and July 2010, we conducted individual interviews with 51 of these farmers and ranchers, randomly selected from this list. Each participant was interviewed using a common semi-structured approach to ensure that participants addressed similar topics. These broad topics included: farm history; how farmers direct market their meat; motivations for direct marketing; barriers to direct marketing; interactions with customers; support structures that are available to direct marketers; and their plans for the future. These interviews were audio recorded and were transcribed along with the detailed field-notes that were taken during each interview.

Based on the preliminary analysis of these interview data, a mail-out questionnaire was developed and distributed from October 2009–August 2010, to further explore emerging themes. This seven-page questionnaire consisted of Likert-scale, ranking, and open-ended questions that were split into three topics: attitudes and motivations for direct marketing; government and direct marketing; and demographics and farm characteristics. Each of the 51 interviewees from the previous phase was mailed a questionnaire in addition to the 176 farm households that remained on the master list. Of the 227 mailed surveys, 169 were completed and returned amounting to a relatively high 77% response rate.

Meanwhile, our case study emerged from a crisis that occurred during a field course taught in rural Manitoba by all three authors. On August 28, 2013 the class of 28 students had been scheduled to visit Pam and Clint Cavers, one of the original 51 interviews in the study, who raise animals and direct market fresh and cured meat. Only a few hours before our anticipated arrival, the Cavers’ informed us that a food safety raid was taking place at their farm and that a provincial food inspector was in the process of confiscating their entire inventory of cured meat. Because the incident exemplified the very analysis we were beginning to develop in this research, we systematically documented and analyzed the situation, purposely examining the dynamics through the lens of our emerging grounded theory (Charmaz 2004; Creswell and Plano Clark 2007). Case studies can provide depth, insight and a rich narrative (Gibson-Graham 2006; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007), which helped to refine the outcomes from our larger cross-regional analysis. This experience resulted in many course-related outcomes including an Internet-based campaign of support for the farmers, a participatory video, and an undergraduate thesis that further explored and provided a context for the raid. The thirteen interviews that were conducted as part of the undergraduate research are also drawn upon in this analysis (Ramsay 2014) and are a part of an ongoing participatory action research project on building sustainable local food systems in Manitoba (Anderson and McLachlan 2015).

Using an approach based in grounded theory, we view data collection, analysis, and writing as being an iterative or dialectical process, rather than being mutually exclusive or sequential in nature (Corbin and Strauss 2008). In this way, qualitative data from the surveys and interviews were transcribed and analyzed using Dedoose, an online qualitative data analysis tool, as our project progressed. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (SPSS V17) and were then cross-interpreted with the qualitative findings. The case study brought further conceptual clarity to our emerging findings as we integrated the qualitative, quantitative, and case-study specific data. As part of the grounded theory process, we also reviewed a variety of theoretical frameworks, choosing to relate the emergent typology to Foucault and Gibson-Graham’s theories on governmentality and the ‘politics of possibility,’ which we felt was best suited to describing the situation we were observing. We also continued to revisit the qualitative and quantitative data, as the theoretical framework was being developed to ensure that it continued to resonate with the experiences of the farmers in this research.

The tensions in the relationships between government and grassroots actors affected the way we analyzed and communicated our findings. Normally we attribute quotations to specific participants in order to affirm their voices, local knowledge, and their interpretations of the situation; however, many research participants expressed concerns that government officials could use their statements against them, reflecting fears of surveillance and possible repercussions. Thus, the identities of participants remain anonymous, with the notable exception of the Cavers’ family who has already gone public with their concerns about the actions of the Manitoba government.

Results

In this section, we present the results regarding farmer attitudes towards and experiences with government through their direct-marketing businesses, focusing first on government support programs and second on food safety regulations. These findings are then further developed in our case study, illustrating the various ways that farmers are acted upon, through governmentality, and directly through regulatory limitations, but also the ways they resist and respond through a politics of possibility. In the subsequent discussion section, we cross-interpret these results to develop a typology of four different modes of interaction between grassroots and government.

Farmer attitudes towards government support programs

Many survey respondents generally felt that the support programs at all levels of government were inadequate or inappropriate to farmers interested in local food systems. In total, 56% agreed that direct marketers need more support from government while 69% disagreed that the federal government was committed to supporting direct farm/ranch marketing. Provincial/state governments faired only slightly better, as 56% disagreed that our provincial/state government is committed to supporting direct farm/ranch marketing (Table 1).

Most (74%) respondents recognized there was much more government support for large-scale export-oriented producers such as the corn subsidies offered to farmers in the US while in Canada, funding offered by the national Growing Forward 2 program almost exclusively encourages export-oriented production (National Farmers Union 2013). Many felt there was relatively little, if any, direct support for small-scale, direct marketers. The national agriculture policy framework makes it clear that there is a preference for export agriculture. This reduces the motivation and ability to focus on local programs (South Dakota 121).

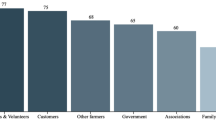

In the absence of government support, many participants identified the importance of the support they had received from other farmers and from local grassroots organizations such as farmers’ market associations. Indeed, when asked to compare the value of different sources of support, all three levels of government were ranked last while the support of other farmers/ranchers and farm organizations all were ranked highest (Table 2).

Participants identified a range of possible approaches by which government supported direct farm marketing. Some identified the role of government as a regulator and certifier of food safety, which can increase consumer confidence in farm products: Being fully licensed and government inspected has provided our customers with more guarantee that the products they buy are safer (British Columbia 198). Others identified various government programs that support the development of direct farm marketing, which were observed as being more prevalent in recent years with the growing interest in local food: There is a growing network of supports for people who are doing direct marketing even in North Dakota…the [State Agriculture] Department is actually doing more. They work with a farmer’s market direct marketing group (North Dakota 402). Indeed, farmers are accessing support programs if they were a good fit with their farm’s needs.

However, farmer attitudes were often critical of government support programs as they found them to be under-resourced or failed to reflect their own priorities and values, but rather emphasized the agenda of governments themselves. Some indicated that they would not accept support even if it were offered, whereas others were frustrated by the lack of support,

You can look on the web but it’s not like there are any subsidies. It’s hard to get grants. You shouldn’t expect that there is going to be any financial assistance for doing it. And I think most small farmers actually are okay with that (Oregon 311).

Although it would certainly have been beneficial for many to have access to support programs that provided resources, skill-development, and funding, but these programs were often seen as not being worth the effort because of the bureaucratic nature of their implementation, […] but then so often you get grants and there are stipulations to it. You have a certain standard then or certain rules that you have to follow, that makes it more expensive in the end too (British Columbia 602). Some respondents described a distrust of government and a desire to avoid the surveillance that might arise from formally participating in government programs. A farmer from Manitoba described how program funding was tied to providing information that might ultimately be (mis)used to track and penalize the farm in the future, I don’t know what they do with all that info and I don’t trust their judgment or think they have the right ethos to be trusted with the details of our farm (Manitoba 521). Others commented that existing support programs tended to encourage farmers to adopt the values and practices that were congruent with the dominant food system rather than allowing for innovations and experiments that deviated from the status quo, I don’t know what they want, but it seems as if they want us to fit into the existing system that’s already built (Manitoba 508).

Farmer attitudes towards food safety regulations

Many (70%) farmers identified food safety regulations as a barrier to direct marketing (Table 3) and to the wider development of local food systems, It’s like that one level of control that kind of keeps this [local food] from getting very big (Oregon 304). Food safety regulations were often viewed as an impediment to diversifying and innovating in local food markets. Regulations were described as being designed for large-scale operations and as impractical or unaffordable for smaller scale producers to comply with,

They need a really complicated inspection system. It’s called HACCP [Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point] …It’s a binder. It’s about 300 to 400 pages. Every worker, every line in a big factory has to check off that they’ve followed certain procedures on a regular basis. The problem is, when you impose that complicated rigorous food safety inspection system on a small farm, it’s impossible (Manitoba 508).

The application of one-size-fits-all regulations was seen to favour larger processors while putting small processors at further disadvantage,

… We have limited processing facilities because Cargill has taken over them. […] They limit our opportunities for processing because they take it all, limit our opportunities for marketing because they control it all, limit our opportunities for where you buy your feed, where you buy your fertilizer, […] because it’s all monopolized and it’s something that changed over the last 25 years (Manitoba 505).

Farmers described how the regulatory burden had led to the closure of smaller scale abattoirs and butchers, thereby eroding local processing capacity and creating a bottleneck in the local food system (see also Miewald et al. 2013a). Additionally, the loss of local processing facilities increased costs and travel time for farmers bringing their animals to market (see also Miewald et al. 2013b). Thus, one farmer from Oregon described needing to make a 400-mile (approximately 650 km) round trip to the nearest federally inspected processor.

Farmers expressed frustration with poorly defined regulations, inconsistent interpretations of regulations, and the hostile culture of most regulatory enforcement. Many (61%) felt that government regulations for direct marketing are not clearly defined and that there was often little support for farmers to navigate poorly articulated regulations (Table 3). The excessive time and resources required to understand and comply with these regulations, which often amounted to a moving target, increased the transaction costs for local food businesses, and created a substantial disincentive for farmers and value-added processors, Every one of those compliance things takes up time, takes up a lot of money and really limits opportunity (Oregon 304).

Many indicated that inspector interpretations of the guidelines and regulations varied over time and that there were substantial differences in interpretation between inspectors, it just depends on what side of the bed some of these inspectors get up on each day as to whether they are going to be cooperative, or whether they’re going to be argumentative (North Dakota 404). A farmer from Oregon explained that renovations initially budgeted at $10,000, ultimately cost him approximately $25,000 because different inspectors imposed conflicting requirements. In turn, a farmer from Manitoba explained how he cancelled his plans to develop an on-farm meat processing plant after witnessing the mounting unforeseen costs faced by local abattoirs and butchers as a result of the inconsistent interpretation of poorly defined regulations.

The majority (81%) of participants were concerned that future changes in food safety regulation will threaten the viability of [their] direct marketing business (Table 3). A Manitoba farmer explained,

Then those are the grey areas and all of a sudden the government gets something in its head and the inspectors come in, and the grey areas are all of a sudden changed. They’re not grey anymore and we’re getting fined (Manitoba 508).

Some also identified the presence of a hostile surveillance culture that was disconnected from the needs of small-scale farms and that pressured them to be more cautious and conservative when developing their businesses (see also McMahon 2009). Farmers were fearful that inspectors might show up unannounced, that their neighbours might report them for suspicious behaviours, or that potential customers might actually be undercover inspectors,

You know when you get a call out of the blue there is always this feeling like - hmmm, is this a federal inspector checking to see if I’m doing things right? We’re trying to do things right but you never know for sure if you’ve met all the regulations or not because it’s not easy (North Dakota 402).

The lack of clear regulations, inconsistent interpretation, and distrust towards government discouraged many farmers from innovating and taking business risks. Some indicated that asking for clarification from government was risky in-of-itself, because it might draw unwanted attention from regulators. Many farmers face the conundrum of needing to be highly visible to attract new customers and grow their business on one hand and the need to avoid the attention of inspectors in the context of an amorphous and sometimes hostile regulatory and enforcement context on the other hand.

Despite these risks, many farmers contested the imposition of regulations in both implicit and explicit ways. Indeed, interviewees frequently mentioned that many farmers challenged the rules and regulations by operating ‘under the radar’, knowingly circumventing the rules while providing food that they knew to be safe.

We try to do what’s right in terms of not breaking any laws, but you might bend a few. There are some regulations in terms of how you store stuff and like I mentioned before that we’re not really allowed to bring stuff back to the farm, but we do (Manitoba 505).

In other cases, especially where there were few or no government-sanctioned processing facilities, some farmers opted out of the regulatory system by illegally processing uninspected meat themselves and marketing it on the black market.

There are some areas of the province where it’s just a black hole and undoubtedly any local meat is all illegal. So there’re a few people who are brazen enough to advertise in some of the local rags saying they’ve got meat but I think most people have just really gone underground with it (British Columbia 601).

Other farmers described the need to explicitly contest and challenge inappropriate regulations and the need for allied organizations to advocate for change,

I see Friends of Family Farmers offering the biggest strength of having somebody full-time in that liaison room who can be engaging with the legislature and then come back to all the grassroots and activate the troops (Oregon 311).

Indeed, over the course of this research, struggles to contest and reform food safety regulations took place in three of the four regions reflected in our project. In Oregon, new food safety regulations addressed the needs of direct marketers (Brekken 2012) whereas in British Columbia a multi-scaled approach to food safety regulations was introduced in 2010 (Miewald et al. 2013a). In the next section, we focus in on an in-depth case study that details such a struggle that emerged in Manitoba in 2013.

Contradictions in local food policy in Manitoba: a case study

Although Manitoba has a long and rich history of Indigenous food systems, government and industry attention has centered on the export-oriented markets of grains/oilseeds and meat since the province was settled in the 1870s. As the provincial agriculture and food agency, Manitoba Agriculture, Food, and Rural Development (MAFRD) is simultaneously responsible for promoting agriculture and food businesses as well as conducting food safety inspections of local meat and other food products. At the period of this study, three core programs exist to support a growing interest in local food within the province: the ‘Buy Manitoba’ campaign, administered by the Manitoba Food Processers Association (CBC Manitoba 2013a); Open Farm Day, an annual event that purports to celebrate family farms (Manitoba Government 2010); and the ‘Great Manitoba Food Fight’ which promotes direct marketers within the province (Manitoba Government 2013). These programs and their contradictions are explored in detail next.

In 2012, MAFRD launched a program called ‘Buy Manitoba’ in response to growing interest in local food (Manitoba Government 2012). A cross-sectorial committee was formed to develop the terms of reference of the program. Initially, it was composed exclusively of larger corporate stakeholders and industry associations and none of the Manitoban NGOs that focused on promoting and representing local sustainable food systems were invited. Several grassroots groups requested a seat on the committee, which they ultimately were granted. However, these groups were marginalized throughout the process, especially when it was decided that industry groups who were in a position to provide matching funding would have greatest control over the program. Although the ‘Buy Manitoba’ program had the potential to directly support the growing number of pioneering small-scale farmers and processors in the province, it ultimately became a labeling scheme that only identified Manitoba-made products. The labeling focused on the largest corporate food retailers such as Safeway, as they were able to provide the expected matching funds. The value of the labeling scheme was also questioned by some, as products that had been processed but not produced in the province were labeled as “Made in Manitoba”—including Coca-Cola (CBC 2013a).

A second local food program called ‘Open Farm Day’ was initiated by MAFRD in 2010 (Manitoba Government 2010). Based on similar popular programs in Eastern Canada and responding to a growing interest in re-connecting farmers and consumers, Open Farm Day aimed to encourage farmers to open up their farms to the general public. The program provided a needed boost to direct marketers in the province. However, Open Farm Day was also viewed by some as representing a narrow and romanticized view of agriculture while obscuring the neoliberal focus of the province’s agriculture policy. One farmer from Manitoba describes his experience,

Open Farm Day is great but it shows a very rosy picture of what farming is about. People come out to our farm and get the picture that this is what farming is like in Manitoba and generally, this just isn’t the case… We were asked [by MAFRD] not to contrast our operation from conventional agriculture (Manitoba 510).

Organizing Open Farm day represents a minimal investment and allows the Manitoba Government to appear to be playing a highly visible role in supporting local food while also acting to shape and control the discourse around local food in the province.

Finally, the ‘Great Manitoba Food Fight’ became an annual event organized by MAFRD and the Assiniboine Community College Manitoba Institute of Culinary Arts as a way of showcasing farmers and chefs interested in promoting local food (Manitoba Government 2013). Beginning in 2005, the event paired ten value-added producers with chefs to build a meal based on an original local food product that the farmers had created. The winners received cash and in-kind support to commercialize their prize-winning product. While the winning farmer benefitted, such programs focus on local food as being a commercial product and generally obscure the importance of the social, cultural, ecological, and political processes that represent a more holistic, critical, and transformative approach to developing local food networks (Winter 2003). In this way, farmers were encouraged and supported to develop commercial products as individuals whereas any support for the wider development of local food networks and larger infrastructure remained completely absent.

Harborside farms: the real Manitoba food fight

So one arm gave us the money, and the other one is seizing it (Pam Cavers, Manitoba, 2013).

Pam and Clint Cavers and their three children operate Harborside Farms near Pilot Mound, Manitoba where they sell fresh and cured meats. In September 2007, they opened a meat shop and a year later that they began to research the production of cured meats such as prosciutto, salumi, and soppressata. Throughout this process, the meat shop was inspected several times including in 2011 when MAFRD was first notified of the Cavers’ interest in expanding their business operation to include the marketing of local cured meats. Since the Cavers’ were not producing their meat for export, they fell under the jurisdiction of the provincial rather than the federal government. However, there were no rules for the production of cured meat in Manitoba, therefore the guidelines outlined by the federal Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) were used by provincial inspectors to direct the process of establishing a safe product. These guidelines for the processing of ‘ready-to-eat’ foods state that food must be stored at a certain temperature and that such meats must be stored separately from fresh meat (CFIA 2014), guidelines that the Cavers’ strove to follow even though they produced very little cured meat. In fact, they had only about $8000 worth of product available in 2013, which accounted for less than ten percent of their annual sales.

In 2013, the Cavers’ were invited to participate in the Great Manitoba Food Fight by their local MAFRD representative, which they ultimately won after entering their cured meat products. The Cavers‘ welcomed the $10,000 cash prize and the offer of technical and marketing support. However, in June 2013—only 3 months after the competition—a new inspector was assigned to the Cavers’ case. The guidelines were reinterpreted and the Cavers’ were required to cease any production until they purchased expensive instruments for testing the pH of their cured products and until they renovated their facilities. The Cavers’ ceased selling their product and began exploring strategies that would allow them to comply with the newly imposed requirements.

On Wednesday, August 28, 2013, MAFRD inspectors served Harborside Farm with a ‘Seize and Destroy’ order, citing “non-physical evidence” that the Cavers’ had continued selling their cured meat (see CBC 2013b). The Cavers’ refute these charges and indicate that cured meats have a long shelf life and that restaurants might have continued selling products that had been purchased prior to June. Pam Cavers refused entry to the inspectors and then called the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, who were highly critical of the aggressive tactics used by the inspectors and attempted to mediate. The impasse was resolved when the inspectors agreed to seize but not to destroy the product. Unfortunately, the product was destroyed a few weeks later without notifying the family and the Cavers’ were fined $1400, which when combined with the value of the destroyed product, amounted to $10,000 in penalties—ironically, this was the equivalent value of the prize they had been awarded earlier by the same provincial government department. Months later, the charges against the Cavers’ were dropped without explanation, compensation, or any admission of wrongdoing on the part of MAFRD. The emotional impact of this event on the entire Cavers family was significant. Pam Cavers described feeling anxious and afraid when the inspectors arrived and for weeks after the incident the family felt nervous whenever a car they did not recognize drove up to their farm.

The long-term implications of these government actions for the Cavers’ are unclear. While there have been significant financial effects, a diverse group of NGOs, students, and customers fundraised to help offset legal expenses and also created a website that acted to make the information about this conflict widely available (www.realmanitobafoodfight.ca). However, at the time of publication, the Cavers’ are still not allowed to produce cured meats using traditional methods, although they continue to sell fresh meat products. Further, in their subsequent interactions with food safety inspectors, the Caver’s were implicitly threatened to stop speaking out publically, They told us, ‘when you speak to the media, it makes it very difficult to work with you’ (Clint Cavers, Manitoba, 2013). After the Cavers’ raid, two other direct marketing farms also received surprise inspections by MAFRD. Some farmers were concerned that they were being targeted because of their increased public presence,

Inspectors are getting more savvy and regularly scour the Internet to identify and target direct farm marketers, and as farmers reach out to try to promote what we are doing, we at the same time allow the government into our farm before they set foot here physically (Clint Cavers, Manitoba, 2013).

The public campaign ‘The Real Manitoba Food Fight’ ultimately resulted in the creation of an advocacy group initially called ‘Farmers and Eaters Sharing the Table’ (FEAST) which was then renamed ‘Sharing the Table Manitoba’. These campaigns and coalitions act as a vehicle for farmers, fishers and hunters, processors, consumers and other stakeholders to advocate for policies that would support sustainable local food systems in the province. The initial campaign capitalized on the political opportunity that emerged from the raid on the Cavers’ farm as a leverage point to advocate for change. Yet, the resulting public pressure also opened new opportunities for cooperation between farmers and the provincial government.

On October 18, 2013, an initial meeting was held between farmers, representatives of MAFRD, and civil society actors. These initial efforts were followed up by MAFRD by launching the creation of a Small Farmers Roundtable, also made up of industry, government, and farmer representatives, and chaired by the province’s former Chief Veterinary Officer. The resulting report identified the many problems related to extension, regulations, quota systems, etc. (Small Scale Food Manitoba Working Group 2015). Co-generated by government and civil society actors, the report has the potential to act as a point of departure for policy reform in the province and to further mobilize different actors in civil society. More recently an organization has been formed, in part as a response to this report, to work directly with government called the Direct Farm Marketing Association of Manitoba (Anderson et al. in press). The outcomes of this process remain unclear as survey findings from the report were denied to members of ‘Sharing the Table’ and efforts by farmers to organize themselves have yet to result in any substantial policy changes resulting in some becoming cynical about the potential for achieving meaningful change.

Discussion: containing, coopting, contesting, and collaborating

The findings from our multi-regional and case study research suggest a typology made up of four interrelated modes of interactions between institutional and grassroots actors regarding local food systems: containing, coopting, contesting, and collaborating (Fig. 1). The horizontal axis compares implicit and overt methods of action, which range from the actions dominated by institutions to the actions dominated by grassroots actors. The degree to which actions are overt or implicit, meaning whether they are direct and easily observable or whether they constitute subtle changes in discourse and attitudes, also varies. While all actions can have both overt and implicit characteristics, coopting and containing are often subtler and implicit while contesting and collaborating tend to be more obvious and explicit. The first two types of interactions, containing and coopting, see greater influence from institutional actors in shaping food systems through the use of governmentality or direct governance practices. They reflect both the apparent and subtle abilities of government and corporations to reinforce power structures and relations of the dominant neoliberal and productivist system, thereby undermining innovative local food models and effectively denying the agency of farmers as a demonstration of governmentality (Foucault 1991). In these interactions, farmers, consumers, and other food system actors are constructed as passive, consenting, and conforming subjects in the dominant neoliberal and industrial food system (Thompson and Lockie 2013). Government policies reinforce unequal power relations by restricting (containing), often through the direct enforcement of limitations through regulations, or diluting (coopting) emerging grassroots alternatives through technologies of governmentality. The second two types of interactions, contesting and collaborating, demonstrate the influence and agency of grassroots actors. They reflect how community economies and grassroots movements employ a range of strategies and tactics that circumvent, challenge, and countervail the status quo while reflecting what Gibson-Graham (2006) call a politics of possibility.

These types of interactions also vary in the level of agreement between grassroots and institutions, represented on the vertical axis, from the relative alignment of ideologies represented by the processes of coopting and collaboration to the oppositional nature of containing and contesting. All four of these interactions are always changing and can even co-exist for short periods of time as they transition from one relationship to another. They are also dynamic and change over time in predictable ways and in response to shifting political and social opportunities and pressures. As discussed below collaborative efforts between the grassroots and government can be subject to cooptation by the increasingly more influential government actors and eventually become restrictive enough in nature that in turn give rise to explicit and collective resistance expressed as contestation. These politicized grassroots responses in turn pressure and increase the willingness of government to accommodate or collaborate community priorities and concerns and the cycle continues (Fig. 1). This typology involves both explicit and implicit strategies where food system actors assert their agency to create food systems that reflect their collectively negotiated values, thus facilitating more meaningful and community-scale change regarding food systems. Together, these interaction types have important implications for farmer subjectivities, the type of production practices and economic relations used by farmers, and the food system as a whole.

Containing

With respect to the first type of interaction, our results suggest that governments at both the national and provincial/state level often contain the development of alternative food systems. Regulatory measures both directly and indirectly constrain grassroots innovation and paths of development that stray from the neoliberal and industrial food paradigm (Fig. 1) (see also McMahon 2009; Miewald et al. 2013b; Denny et al. 2016). Processes and relations of containing can be highly visible where farmers who try to produce food beyond the regulations or push back against them are penalized and even criminalized under the auspices of a risk management in food safety discourse. This was evident in our interviews with farmers and in the Cavers’ case study, but has also played out elsewhere in battles over direct marketing raw milk (Kurtz et al. 2013). Containing is significant because government regulations are disproportionately costly and burdensome for small operators who are rarely the source of major food safety outbreaks (McMahon 2009). In most cases, containment represented a very direct action taken by governments, however the neoliberal capitalist emphasis on competitive advantages results in direct-market producers who focus on trust-based risk management being pushed out by those producers who accepted the risk management paradigm based on phytosanitation procedures (McMahon 2009; Stuart and Worosz 2011; Miewald et al. 2013b; Denny et al. 2016).

However, the mechanisms of containing were not always explicit or obvious and often occurred through subtler changes in behaviours and attitudes on the part of regulators and modes of self-regulation on the part of farmers. For example, some farmers avoided expanding or exploring new innovations on their farms because of the risks of constantly changing and inconsistently interpreted regulations by enforcement officials. High profile raids and antagonistic interactions with regulators also signal a hostile or uncertain regulatory culture. In this context, farmers indicated they were much more reserved in their planning, no longer trusted expanding into a regulatory grey zone, avoided promoting their businesses, and were deterred from questioning or challenging regulations due to risk of reprisal as an anti-reflexive practice (Stuart and Worosz 2011). In this case, active enforcement of regulations is combined with the modes of governmentality that arise from the inconsistency of regulatory enforcement, surveillance culture, and the ‘making of examples’ of innovators that deviate from the status quo. This context fosters self-governing subjects that regulate their everyday decisions to avoid risk of operating outside of the rules, norms and pressures of the dominant food system. Additionally, the ‘go-big-or-go-home’ discourse in food and agriculture implies that small farms and processors are irrelevant and doomed to failure unless they conform to the productivist, industrial, and centralized approaches tied up in the neoliberal food system. Thus, the path dependence of the dominant system manifests itself by normalizing and influencing the ‘conduct of conduct’ of citizens to discourage alternative practices and to encourage conformity to the dominant system (Guthman 2008a, b; Stuart and Worosz 2011).

Coopting

With respect to the second type of interaction, the relationship between government and grassroots can serve to coopt ideas and innovations emerging from the bottom up and thus undermine the transformative potential of alternative local food systems (Fig. 1). In our study, direct marketers received very little financial or program support from government, and where support was offered it often encouraged farmers to focus on individual commercialization or expansion. In effect, government support programs tended to direct farmers to pursue the dominant growth trajectory in agriculture and in food processing. Cooptation also occurred when funding, support and extension programs bolstered actors who already held power in the dominant system (e.g. corporate retailers) to benefit from local food systems. In the Manitoba case study, the “Buy Manitoba” local food program was aimed primarily at supermarkets and food processors, actors that were already well established in the dominant food system, and had little benefit for direct farm marketers. These findings resonate with studies conducted in Australia (Andrée et al. 2010) and England (Ilbery et al. 2010) that found government programs encouraged farmers and processors to conform to a productivist and neoliberal model of growth, thus undermining the potential of civic, cooperative and alternative food economies.

The process of coopting was also expressed through the attitudes and actions of farmers themselves—a process that reflects the ongoing enrolment of farmers as subjects of neoliberal governmentality. The pervasive emphasis of government programs on the commercialization of products, on scaling up, and on channeling products through existing corporate retail rather than through grassroots food networks can shape the perspective of participants towards these pathways. In a study of farmers’ self-identity in Iowa (McGuire et al. 2013), farmers often began to internalize neoliberal values of these programs, such as competitiveness, specialization, and supporting laissez-faire free market capitalism. In our study, farmers often expressed a strong sense of independence and entrepreneurship, rejecting any government assistance but also implicitly accepting the conventionalization of ‘buy local’ efforts as inevitable. Indeed, many of the arguments for direct farm marketing reflect the mantra of ‘consumer choice’ rather than arguments for alternative relationships around food based on trust, reciprocity, and mutual accountability. At times, such sentiments were expressed during the ‘Real Manitoba Food Fight’, where some argued that these artisanal products be allowed based on the notion of ‘consumer choice,’ rather than any broader and more politicized commitment to alternative food systems. In this way, the coopting interaction reflected a process of governmentality where the influence of government was to change common sense notions of how farming should be done and what it meant to produce safe food.

Contesting

The third type of interaction, contesting, occurred when farmers and other civil society actors took individual and collective action to challenge government and its complicity in serving the interests of powerful actors in the dominant system (Fig. 1). Here, citizens consciously rejected cooptation and containment by government, and mobilized as social and political agents reflecting a politics of possibility (Gibson-Graham 2006). In our study, rural and urban actors involved in the Real Manitoba Food Fight explicitly contested the government’s role in suppressing local food systems in Manitoba. Similarly, farmers and food activists in BC protested changes to the Meat Inspection Regulations in 2004 (Miewald et al. 2013b) and farmers from Oregon lobbied to change state regulations and policy to better support local food (Brekken 2012). Importantly, these acts of contestation were successful because they engaged with a wide diversity of citizens, not just farmers themselves, to work collectively to create new subjects that were empowered. These local acts of contestation are occurring across multiple sites drawing from the discourses of community food economies and food sovereignty and can be seen as representing a larger social movement (Escobar 2001; Fairbairn 2012; Levkoe 2014).

While contesting is often an overt and public action, farmers and their customers also contest implicitly and covertly by pushing the boundaries of ‘grey areas’ of regulations or by ignoring or circumventing regulations in the black market. Public actions were sometimes seen as riskier than the covert contestation that occurred through this engagement in alternative markets. Moreover, Dunn (2003) found that engaging in underground markets was a viable form of farmer contestation to the imposition of food safety standards in Poland. In our study, these acts were demonstrated in all four regions of our study where small farmers felt unfairly disadvantaged by regulations, especially for those who were in areas of low population density or who were greater distances from regulated processors. Black market responses included the illegal sale of uninspected meat that had been processed on-farm. Grey market responses included using labels that failed to meet regulations, engaging in online sales (in some jurisdictions), or delivering items that are typically only available at the farm gate such as eggs. These acts of contesting the food system fit within Gibson-Graham (2008)’s diverse economic relationships and their (2006) ‘politics of possibility.’ They argue that by building alternative and diverse economies that include relationships like CSAs (community shared agriculture) or other work-share arrangements (Wilson 2013) and community food hubs (Ballamingie and Walker 2013), citizens are contesting the current food system by subverting neoliberal and productivist governmentality through acts of self-cultivation and collective action (Gibson-Graham 2008). However, contesting requires energy on the part of grassroots organizers and these actions may fail because networks and individuals simply do not have the capacity or resources to maintain resistance. It is also important to recognize that this mode of interaction is often unstable and sometimes even dangerous for individuals who can become targeted by authorities, at least until supported by wider social movements that can pressure governments to accommodate and sometimes collaborate with grassroots actors.

Collaborating

The fourth type of interaction, collaborating, occurs when government and grassroots actors work in authentic and balanced partnerships to build local food economies together (Fig. 1). In this case, governments provide genuine opportunities for farmers and citizens to help shape policy, regulations, and practices related to local food and, in turn, farmers understand themselves to be active participants in this process. This is accomplished when support programs are developed with partners to provide adequate flexibility for farmers to pursue their own innovations and to build community food systems. At the collective level, governments can engage with grassroots groups of farmers and allies to meaningfully engage in democratic decision-making processes and equalize power relationships among actors. In our study, governments in Manitoba and Oregon have ostensibly responded to the requests for small-size farmers to be included in the creation of new regulations.

The ability to collaborate with government in policy arenas often requires collective action amongst farmers and can be strengthened through cross-sectorial networks to represent the joint needs of farmers and local food allies including eaters, processors and chefs. Often taking the form of “Friends of Family Farmers” (2015) groups, these coalitions can unite eaters and food producers and allow non-farm advocates to push for change while protecting farmers who may otherwise be reluctant to speak out against regulators for fear of retribution. In Manitoba for example, ‘Sharing the Table Manitoba’ included chefs, researchers, food and social justice organizers, and consumers in their membership, in part because urban actors often had fewer concerns about negative repercussions from government (Anderson et al. in press). In Oregon and British Columbia, grassroots campaigns have resulted in collaborative efforts between civil society groups and regulators resulting in the adoption of a regulatory framework that better supports the development of local food systems (Brekken 2012; Miewald et al. 2013a).

These collaborative efforts require knowledge sharing and viable networks to build relationships and bring about long-term change and represent opportunities to cultivate new subjectivities among grassroots actors (Tovey 2009; Wilson 2013; Blay-Palmer et al. 2015). Effective collaboration requires a sustained commitment by government to co-create a power-equalizing deliberative space where citizens are able to co-produce agendas, choose topics to address, and able to generate pragmatic outcomes that address their needs. However, power sharing is generally rare in the context of top-down policy making. These tenuous spaces become opportunities for citizens to gain a sense of agency and trust in institutional and policy processes and have great potential to support community based economies and food systems. On the other hand, when the influence of elites and corporations retain or regain control, collaboration can quickly become cooptation where citizens are rather enrolled in superficial public participation in policy-making that legitimizes the agenda of government but denies the agency of grassroots actors.

Dynamics among types of interaction

Although the four types of interaction between government and grassroots actors might be viewed in isolation from each other, our results indicate a dynamic relationship between the four types that evolves over time as subjectivities and power relationships are constantly shifting. In the Manitoba-based case study (Fig. 2), grassroots actors gained agency with the high-profile incident on the Cavers’ farm that revealed the contradictions and limitations of provincial government food safety regulations. The resulting mobilization of communities and collective political action (contesting) increased the grassroots agency and political potential to create systemic change in provincial policy. In this example, the process began when the Cavers’ initially researched and develop their cured meats with support from inspectors (collaborating), but faced challenges with narrowly defined regulations that emphasized commercialization and shifted emphasis away from the community food systems (coopting). Later, their products were seized and ultimately destroyed by government inspectors and they faced a great deal of hostility from inspectors and from food safety authorities in the province (containing). This incident catalyzed a strong grassroots political response (contesting), which then pressured the government to establish a cross-sectorial regulatory roundtable that is still working to develop more palatable alternatives to one-size-fits all regulations (collaborating) (Fig. 2). No doubt the situation will continue to evolve, and early feedback suggests that some of the more radical grassroots actors are frustrated by the government-dominated process, which has thus far only resulted in a few minor concessions (coopting).

Occasions to collaborate effectively with government are rare but important opportunities to affect change. The situation in Manitoba continues to evolve and while there have already been important gains made, there are concerns that any prospects for effective collaboration will be diluted as the political opportunity that arose through the high profile Cavers case has subsided and government faces less pressure to work with grassroots actors (Anderson et al. in press). Similar interrelations were also evident in other regions and show how the dynamic processes of containing, coopting, contesting and collaborating rely on tenuous power relations that can change suddenly. For example, in British Columbia when food safety regulations were changed, farmers’ livelihoods were threatened (containment) which stimulated both implicit (black market selling) and overt (political action) contesting which then led to collaboration with government and ultimately to policy change (Miewald et al. 2013a, b). One of the most common way that governments limit change to the status quo is by directing contesting into a consultative process that are actually disingenuous forms of collaboration which then lead to modest reforms rather than more the transformative changes needed to enable local food to contribute to a more sustainable, viable and just food system (Thompson and Lockie 2013). This variation of coopting is used to limit the aspirations of grassroots who as a result are less hopeful about their ability to affect system change.

Existing research that uses of the theories of governmentality and politics of possibility looks mainly at the static status of food systems or explores primarily the influence of either government or civil society. For example, Harris (2009) argued that governmentality, particularly as it applies to neoliberalism in the food system, is often credited with more power and influence than it is due which serves only to further entrench its significance. Meanwhile, Gibson-Graham’s approach has been argued to place too much emphasis on community agency and autonomy without considering the barriers that institutions can create (Glassman 2003). Whereas these frameworks can give an absolute impression of either domination or agency, our framework bridges these two perspectives by examining how governmentality and a politics of possibility are dialectically related through the four interrelated modes of interaction we propose. Our typology resonates with the assertion that subject formation is a complex process that is neither uniform nor universal while also exploring the social construction of subjectivities due to the manipulation of discourse through governmentality (Foucault 1991; Gibson-Graham 2006). Farmers and citizens in local food systems are able to resist their subjugation as neoliberal and productivist subjects, but this is most effective when the means by which this subjection occurs is a made visible. Furthermore, by understanding the relations between these types of actions as cyclical and dynamic, much like the seasons, a cycle to which farmers are well attuned, farmers and grassroots organizers can strategically respond to the limitations and opportunities that arise over time.

Conclusion and implications

This typology provides a dynamic framework to understand how the agency of grassroots stakeholders is shaped through the dialectical pressures of neoliberal governmentality in tension with the creative resistances of individuals, communities, and allied networks of support. Through processes of individual and collective agency, farmers and citizens are rejecting their construction as neoliberal subjects and instead are engaged in processes of resubjectification (Gibson-Graham 2006) as agents that are building more just and sustainable food economies. Our study showed how government policy and regulation play a substantial role in the governing of local food systems and in shaping the way that actors perceive their role and their agency to make change. Government influence goes beyond the imposition of direct regulation on individual subjects to include the power of governmentality to cultivating self-regulating subjects who internalize the dominant neoliberal logics. Examples included farmers who reluctantly engaged with support programs that often failed to reflect their values and the self-regulation of farmers who avoided any actions that put them at risk of punishment. Although our findings indicated that there is often some government support for local food systems, they also indicated that such policy and regulation mostly worked to suppress or dilute meaningful alternatives and often served to conventionalize ‘local food’. However, food producers and allies in grassroots movements continue to actively contest policies and regulations by challenging hostile governments to open more space for bottom-up development of alternatives. Through collective action, individuals build alternative food relations and work together to contest the dominant food system, and in turn cultivate new subjectivities and gain agency in their struggles (Gibson-Graham 2003). There are other important sources of support that are gaining momentum, primarily farmer-driven initiatives, and to a lesser degree urban-based consumer groups and environmental NGOs, which are all acting to shift agency towards community actors. Although there is potential for meaningful collaboration between grassroots actors and government, in most cases government and industries ultimately act to undermine these efforts and the actions begin to resemble cooptation. Thus when working with governments, it is essential for grassroots organizations to be ready to adapt and contest the process when faced with these sometimes highly unequal situations.

These four types of interaction can help shape grassroots strategies for moving forward and transforming food systems in ways that can be sustained into the future: in our study regions in Canada and the U.S. but also the rest of the world. The outcomes of our study show the importance of being aware of the processes of governmentality, and the way these play out in the everyday lives of farmers and rural communities, but also in the ways that farmers and other grassroots stakeholders contest governmentality and create opportunities to collaborate with government on their own terms. Such multi-actor food movements can be seen as part of Gibson-Graham’s vision of an alternative economy and by resisting the processes of cooptation through recognizing its risk and refusing “to see cooptation as a necessary condition of consorting with power” (2006, p. xxvi). The potential of food movements to claim food economies will always be an outcome of political struggles that are rooted in a critical understanding of the ways by which government and other institutions manage their development and undermine their potential. Local food activists are attempting to act at multiple scales through various networks while also acting in a particular place and context to affect local change (Escobar 2001; Levkoe 2014). Ultimately, however, real and sustained grassroots transformation will only become feasible when grassroots actors transcend the local, become politicized, and work with and alongside other actors at multiple scales. In so doing, the transformative potential of these sustainable, community-grounded, and politicized food economies is great indeed.

Abbreviations

- CFIA:

-

Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- HACCP:

-

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point

- MAFRD:

-

Manitoba Agriculture, Food, and Rural Development

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

References

Adams, A.E., and T.E. Shriver. 2010. [Un]common language: The corporate appropriation of alternative agro-food frames. Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25(2): 33–57.

Alkon, A.H. 2013. The socio-nature of local organic food. Antipode 45(3): 663–680. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01056.x.

Akram-Lodhi, H.A. 2013. Hungry for change: Farmers, food justice and the agrarian question. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Allen, P. 2008. Mining for justice in the food system: Perceptions, practices, and possibilities. Agriculture and Human Values 25(2): 157–161. doi:10.1007/s10460-008-9120-6.

Allen, P. 2010. Realizing justice in local food systems. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3: 295–308. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsq015.

Anderson, C. R., Pimbert, M. and Kiss, C. 2015. Building, defending and strengthening agroecology: Global struggles for food sovereignty. Farming Matters. http://www.agroecologynow.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Farming-Matters-Agroecology-EN.pdf. Accessed 5 Dec 2015.

Anderson, C.R., J. Sivilay, and K. Lobe. in press. Community organizing for food systems change: Reflecting on food movement dynamics in Manitoba. In Knowledge for food justice: Participatory and action research approaches, eds. C.R. Anderson, C. Buchanan, M. Chang, J. Sanchez, and T. Wakeford. Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience at Coventry University. Available at: http://www.peoplesknowledge.org.